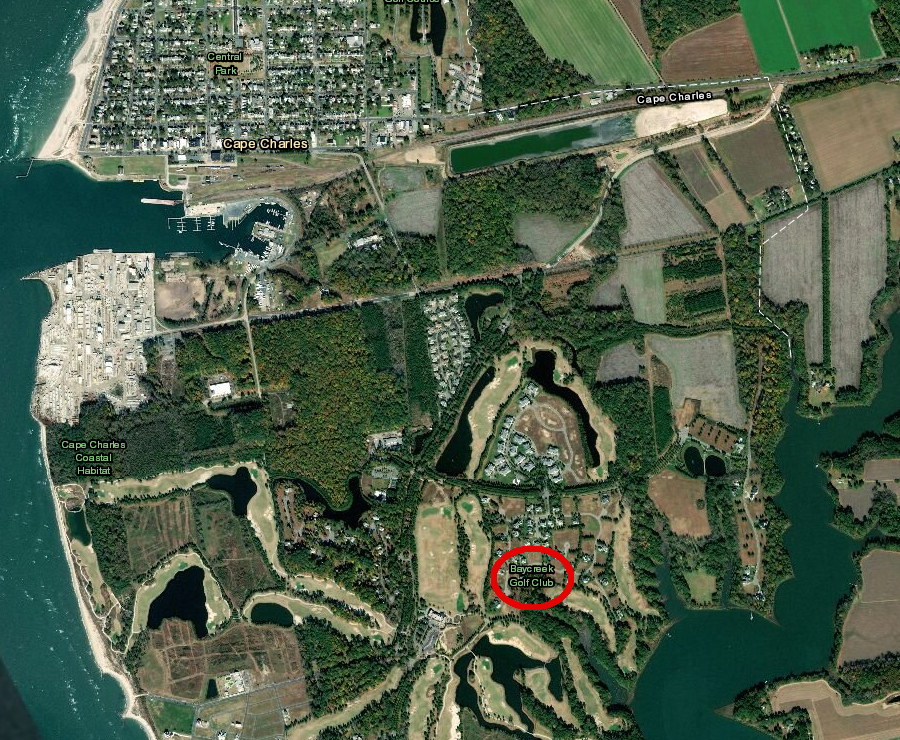

the southern tip of Northampton County has little housing, outside of Cape Charles and a few scattered subdivisions

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the southern tip of Northampton County has little housing, outside of Cape Charles and a few scattered subdivisions

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

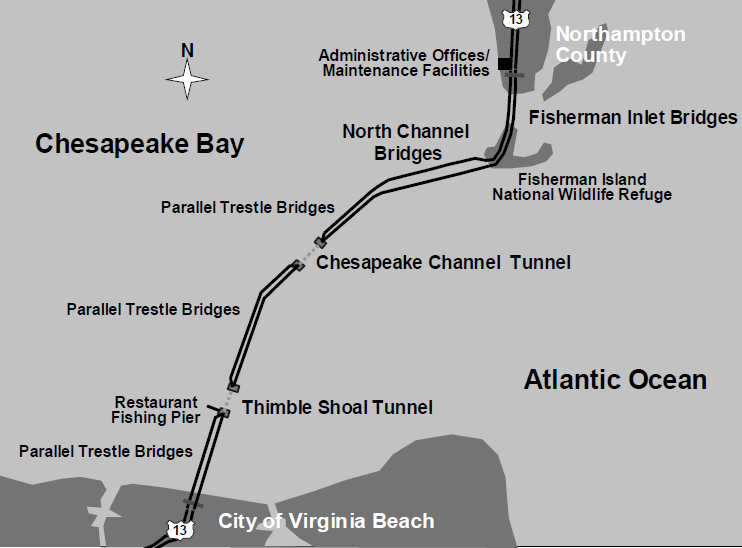

One funding alternative not used yet to fund expansion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is "tax increment financing."

People with full-time jobs in Virginia Beach, Norfolk, and Chesapeake do not typically choose to live in Northampton County, in part because the commute across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel would be long and expensive. If the tolls for commuters were eliminated, there should be an increase in demand for housing located near the bridge-tunnel in Northampton County as more workers in Hampton Roads chose to live in Northampton County. Extra demand would increase the value of those houses, benefitting property owners on the Eastern Shore.

eliminating tolls Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel could incentivize an increase in the density of existing buildings in the southern tip of Northampton County

Source: New York Times, A Map Of Every Building In America

A special tax on the incremental increase in value would capture some of the benefits created for the private property owners by a public policy decision to reduce/eliminate bridge-tunnel tolls. Local officials could designate through zoning where new commercial or industrial development would be approved in Northampton County, and impose an extra tax on all property within that area.

The resulting funds could be directed to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel to replace the lost toll revenue. Tax increment financing also could be used to subsidize the last expansion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, the building of parallel tunnels across the Chesapeake Channel.

Tax increment financing is not a new concept. It was used to subsidize widening of Route 28 in Fairfax/Loudoun counties and construction of the Metrorail's Silver Line in Fairfax and Loudoun counties.

If a special fee were created for Eastern Shore developers to fund bridge-tunnel expansion with extra taxes on new houses, such an arrangement would spread the financial burden beyond the drivers who use the bridge-tunnel. If builders who profited from new construction on the Eastern Shore paid for transportation improvements, then those costs would be incorporated into the price of new houses. Ultimately, Northampton County residents who bought new houses would end up paying a part of the costs for maintaining/expanding the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel to provide faster commutes to jobs in Virginia Beach/Norfolk.

However, there is little local support for increasing government-mandated fees or encouraging suburbanization in Northampton County. In addition, the state law authorizing transportation improvement districts does not authorize taxing homeowners. In addition, there is institutional inertia separating state-based transportation planning and locally-based land use planning.

Even if Northampton County officials wanted to integrate land use, transportation, and tax policies by raising taxes on new housing developments to fund improvements to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, the General Assembly would have to pass special legislation.1

Completion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in 1964 brought the Eastern Shore 90 minutes closer to Virginia Beach/Norfolk. In anticipation of selling houses to both commuters and second-home owners, developers did build golf courses and housing developments such as the Bay Creek Resort & Club in Northampton County.

the Bay Creek subdivision is located just south of the Town of Cape Charles

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

With a faster, cheaper commute, Northampton County could experience the same sprawl as Loudoun, Stafford, Fluvanna, Hanover, and Gloucester counties. From a political geography perspective, landowners and developers planning to convert Eastern Shore agricultural land into new subdivisions would be likely supporters of a proposal to eliminate the fare for commuters crossing the bridge-tunnel. People in the real estate development and sales businesses would get a one-time benefit from building and selling houses, while the new residents would absorb the annual costs of higher taxes.

If commuter transportation to Hampton Roads became "cheap," any Northampton County suburban development boom could be constrained by inadequate supplies of fresh drinking water. Generating freshwater though desalination is expensive due to the energy required to remove the salt. "Aquifer storage and recovery" (pumping Cape Charles' treated wastewater underground to recharge the aquifer) would become an option to supply new residents.

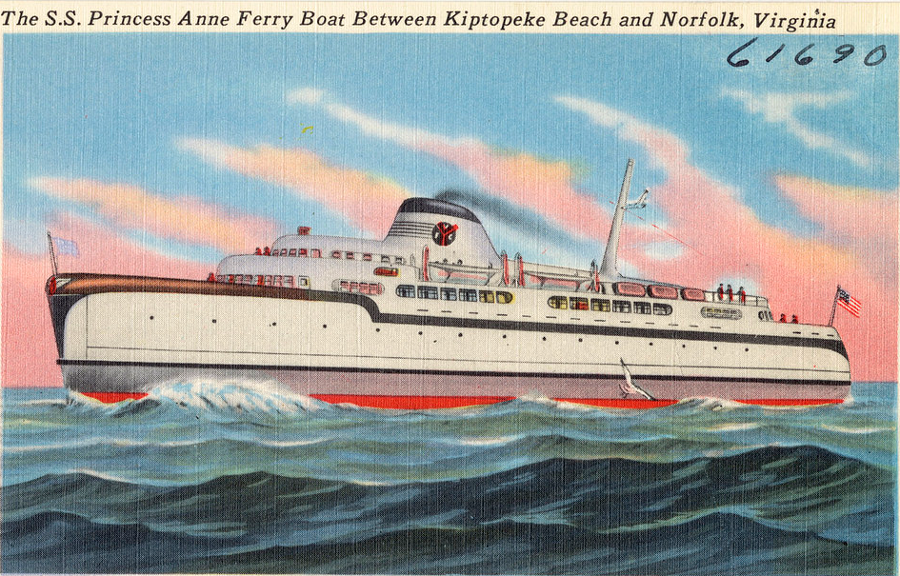

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel replaced 2-hour ferry services with a 30-minute drive when it opened on April 14, 1964

Source: Joint Legislative Audit And Review Commission, The Future Of The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (Figure 1)

Fundamentally, there appears to be limited demand for suburban development in Northampton County for commuting to jobs in Hampton Roads. One clue: replacement of ferries by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in 1964 did not lead to a dramatic increase in suburban sprawl in Northampton County. Land prices on the Eastern Shore remain low compared to other Hampton Roads jurisdictions.

the Virginia Ferry Corporation operated from Kiptopeke in Northampton County, prior to completion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Boston Public Library, The S. S. Princess Anne Ferry Boat between Kiptopeke Beach and Norfolk, Virginia

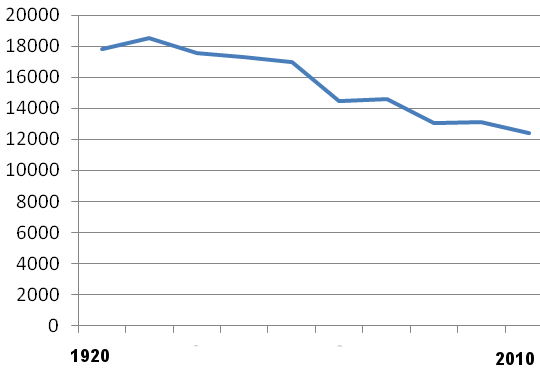

Suburbanization has been slow to affect Northampton County. Population declined steadily from a peak of 18,565 residents in 1930, including a 25% drop between 1960-2010 after the bridge-tunnel was operational. The town of Cape Charles experienced a brief revitalization with old Victorian homes being repaired, but lost 50% of its residents between 1960-2010.

No surge of commuters or retirees has arrived to offset the residents who migrated elsewhere as fishing, oystering, and farming jobs disappeared, and only 12,389 residents were recorded in Northampton County during the 2010 Census. Expectations that the "Atlantic Coast Megalopolis" would expand to the Eastern Shore have not become true.2

population in Northampton County continued to decline even after completion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Bureau of Census, Virginia Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990

Cost of daily commuting to jobs in South Hampton Roads may have been a major factor in the 1960's. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel charged one of the highest tolls in the nation in order to repay construction bonds. Living in Northampton County and working in Hampton Roads involved paying fee that was not required if someone chose to live in a suburb in Virginia Beach.

In 2001, bridge-tunnel managers created a 30% discount for commuters going back and forth between Virginia Beach and Northampton County. The old price was $10/trip, in either direction. Under the new pricing system, a discount was offered for a return trip within 24 hours, reducing the roundtrip price from $20 to $14 if completed within 24 hours. Prices were raised in 2004 to $12 one-way, $17 roundtrip.

In 2013, a new discount was offered: customers making 30 trips in one month (equivalent to commuting for 15 days back and forth to Hampton Roads) would pay just $5 each way.

That reduction did not stimulate a building boom in Northampton County, calling into question the theory that elimination of the bridge-tunnel toll might spur sprawl to the Eastern Shore. Hampton Roads may expand north into Mathews County and west into Isle of Wight County before Northampton County is integrated into the region.

The $10/day cost may have been too high in 2013. By 2018, however, commuters on I-66 in Northern Virginia were paying an average toll of $14/day - and occasionally over $40 for a one-way trip, when congestion was unusually high.3

![]()

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel connected the Eastern Shore to Hampton Roads in 1964

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

1. "Route 28 Highway Transportation Improvement District," Fairfax County, http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/fcdot/rt28taxdistrict.htm (last checked February 13, 2017)

2. "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990," Bureau of Census, 1995, http://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/va190090.txt; "State & County QuickFacts - Northampton County, Virginia," 2010 Census, Bureau of Census, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/51/51131.html; "Bay bridge-tunnel didn't transform Eastern Shore," The Virginian-Pilot, April 16, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/713416 (last checked April 24, 2014)

3. "Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel," Roads to the Future, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel; "CBBT Commission Announces New Commuter Toll Rate To Be Implemented in 2014," Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Commission news release, February 12, 2013, http://www.cbbt.com/commutertoll2014.html; "I-66 will get a third lane inside the Beltway. And the work starts very soon," Washington Business Journal, June 22, 2018, https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2018/06/22/i-66-will-get-a-third-lane-inside-the-beltway-and.html (last checked Octover 25, 2018)