Alexandria was an international seaport from its start in 1749

Source: Library of Congress

Alexandria was an international seaport from its start in 1749

Source: Library of Congress

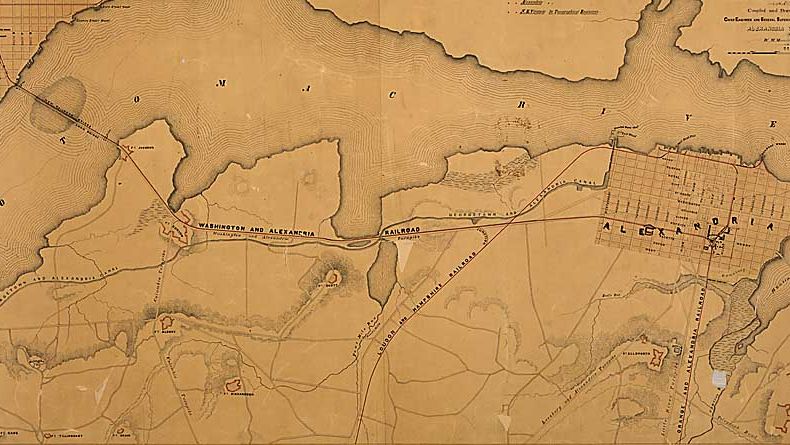

The impacts of transportation networks on early urban development are reflected in the growth of Alexandria. Alexandria merchants financed a transportation network into the backcountry or "hinterland," the farmland west of the Fall Line. Before the Civil War, the city connected its wharves and its stores to farms in the Piedmont - and then to the Shenandoah Valley.

Investments in turnpikes, harbor improvements, canals, and railroads made Alexandria into an economically successful city. Despite the transfer of government responsibility for the city to the District of Columbia and back again, Alexandria was able to outcompete Georgetown across the river as well as Occoquan, Dumfries, and Fredericksburg in Virginia.

Alexandria expanded its wharf space from the natural riverbank deeper into the Potomac River, in part by sinking old ships and dumping dirt between piers that had extended out into the river - and in 2016, one of those ships was uncovered during excavation for the new Indigo Hotel

Source: City of Alexandria, Archaeological Discoveries on the Waterfront: 220 S. Union Street

Alexandria and Dumfries were chartered on the same day in 1749. Both were sponsored by Scottish merchants with comparable economic interests. The towns even have the same pattern of colonial street names - Prince, Duke, etc. Within 25 years after the initial founding date, Alexandria was thriving while Dumfries had already faded into obscurity.

banknotes honored Alexandria's tobacco shipping heritage

Source: City of Alexandria, A Brief History of Alexandria

Dumfries failed to build roads, canals, or railroads to facilitate farmers bringing crops to their docks. Dumfries also failed to prevent soil erosion from silting up the harbor, which is traditionally cited as the reason for the town from failing to grow.

Dumfries business largely ceased when the port was filled with sediment. Efforts to dredge a channel or move downstream failed, and the "Newport" community of townhomes on the south bank is the only modern evidence of the attempt. Dumfries literally became a backwater. The shoreline migrated east as silt filled the old harbor, and the original wharves of Dumfries are now located between the two halves of US 1 running through town.

Dumfries was located at the head of navigation on Quantico Creek, until excessive sediment silted up the harbor

Source: Library of Congress, Preliminary map of northeastern Virginia embracing portions of Prince William, Stafford, and Fauquier counties

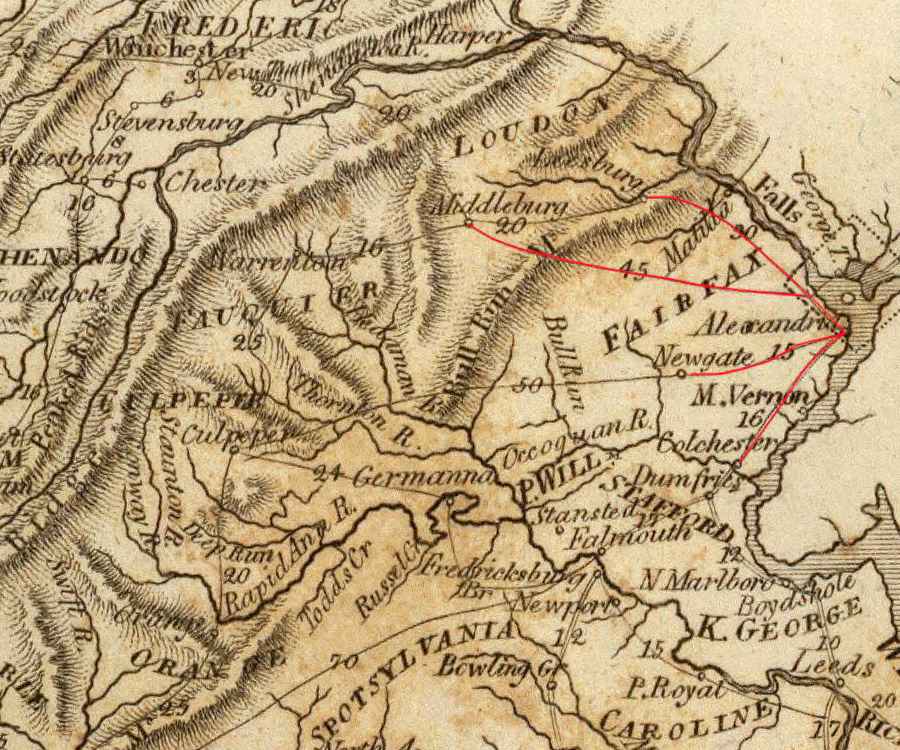

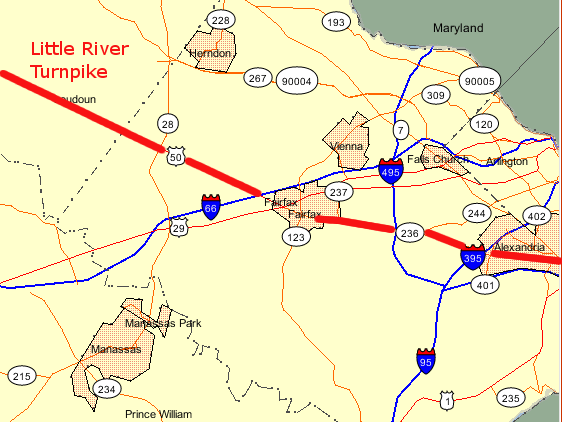

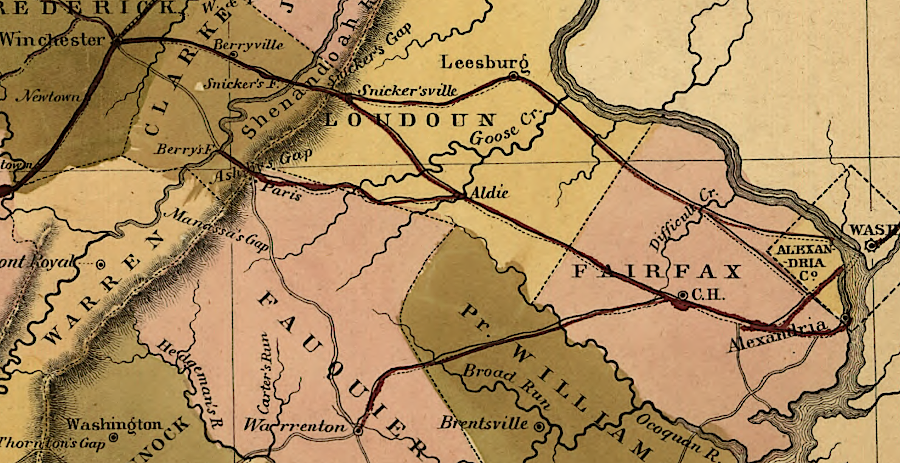

Alexandria merchants linked their port first with farmers in western Fairfax and Loudoun counties. In the 1790's, the city initiated and financed the Little River Turnpike to Aldie, where the Little River cuts through the Blue Ridge. From Alexandria to Jermantown (near the Fairfax campus of George Mason University), the route of the turnpike follows modern US 236. From Jermantown modern US 50 traces the historic turnpike route to Aldie, at the base of the Blue Ridge. The Ashby Gap Turnpike Company later extended the connection west to the crest of the Blue Ridge.

by 1804, Alexandria's road network connected it to all the market centers in the Piedmont as well as the Coastal Plain

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, Virginia (by Samuel Lewis, 1804)

Little River Turnpike

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Online Transportation Information Map

Alexandria built turnpikes (toll roads) into the Piedmont and west across the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the internal improvements of Virginia (by Claudius Crozet, 1848)

The Little River Turnpike was the first successful turnpike in the South. The Philadelphia-Lancaster turnpike, drawing the trade of farmers in southeastern Pennsylvania to Philadelphia and away from Baltimore, was the first successful toll road in North America.

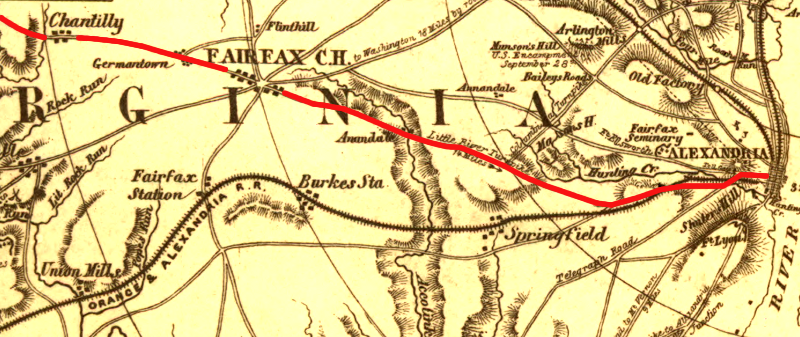

the Little River Turnpike was a toll road linking Alexandria to Aldie, at the base of the Blue Ridge

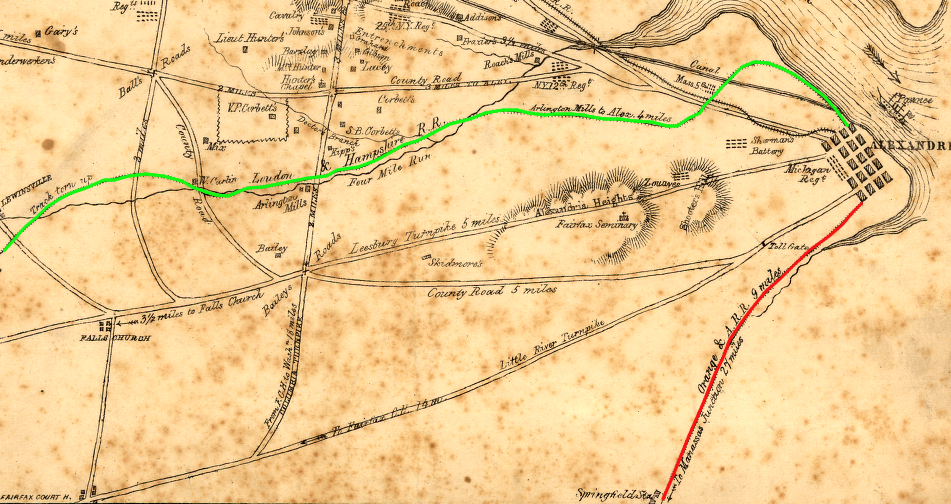

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos. (1861)

Even after paying the toll, farmers throughout western Fairfax and Loudoun counties who used Little River Turnpike could make a greater profit. The road reduced the time required to transport wheat and other bulky items to the port, where competition was greater. Ships from Alexandria could carry farm products to multiple markets, including Europe. Prices for Piedmont farmers were higher, while Alexandria merchants benefited from increased economic activity in their city.

Alexandria transportation network in 1861, highlighting Little River Turnpike

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of Virginia between Washington and Manassas Junction by Charles Magnus

Alexandria's next target was the agricultural trade from Prince William, Fauquier, Culpeper, and Orange counties. City leaders initiated and, with some state funding, built the Warrenton-Alexandria turnpike. It was chartered in 1808 and built in two segments. The stretch from Jermantown on the Little River Turnpike to Buckland in western Prince William County was started in 1812, then completed in 1818 after the War of 1812 ended. The section between Buckland and Warrenton in Fauquier County was built between 1824-27.

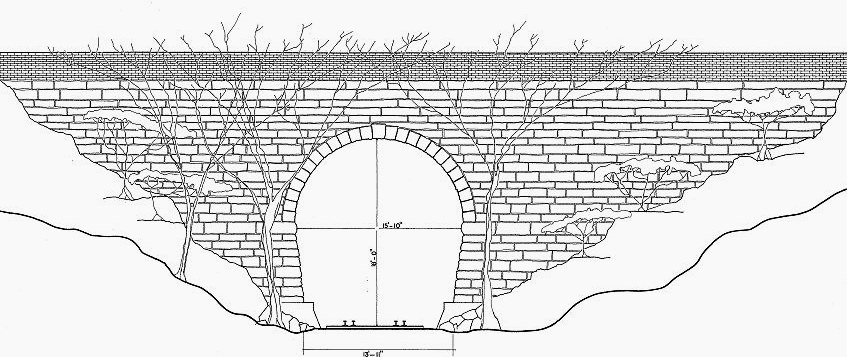

The Stone Bridge was built over Bull Run in 1825. The Stone House, a landmark on what became the Manassas Battlefield, was constructed to collect tolls and support travelers moving between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers.

Today that turnpike is US 29. On the old maps of Alexandria, Arlington, and Fairfax County, it is often referenced as the "Warrenton Turnpike." In Fauquier County, it was often described as the "Alexandria Turnpike." Local residents on one end of the road referred to the turnpike based on the destination at the other end.

the Stone House on Manassas Battlefield was originally a toll house for the Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike

Alexandria merchants were part of the Patowmack Canal and the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal initiatives. The C&O Canal originally ended in the competitive rival town of Georgetown, and the construction of a causeway to Mason's Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island) after 1807 steered river traffic to Georgetown.1

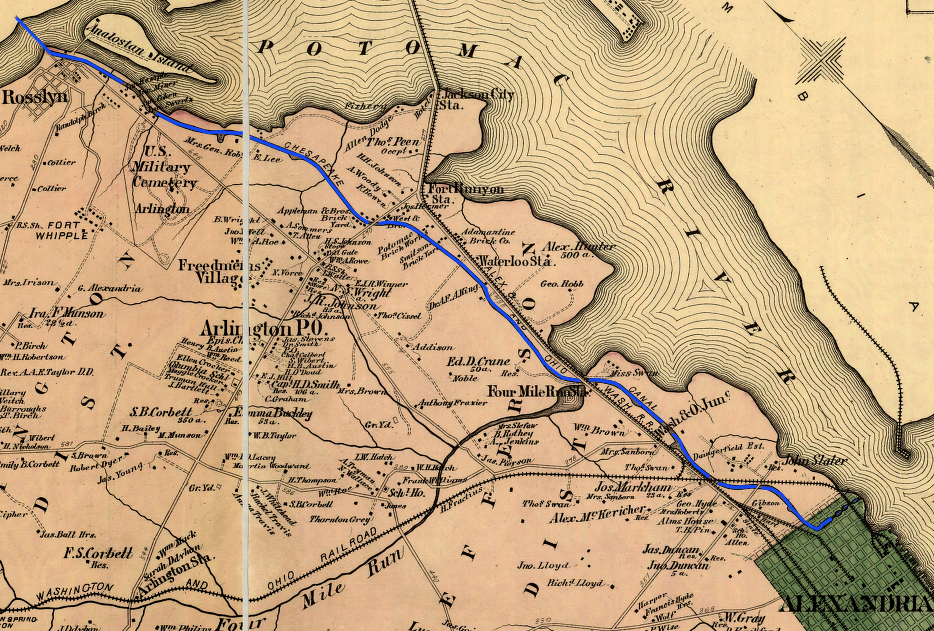

Alexandria arranged for an extension of the C&O Canal to draw traffic to the deeper water port at Alexandria. The Alexandria Canal crossed the Potomac River on Aqueduct Bridge. It opened in 1843, after 10 years of construction. Canal boats finally could go between Alexandria and the C&O Canal while avoiding the risks of flooding, ice, and debris in the Potomac River.

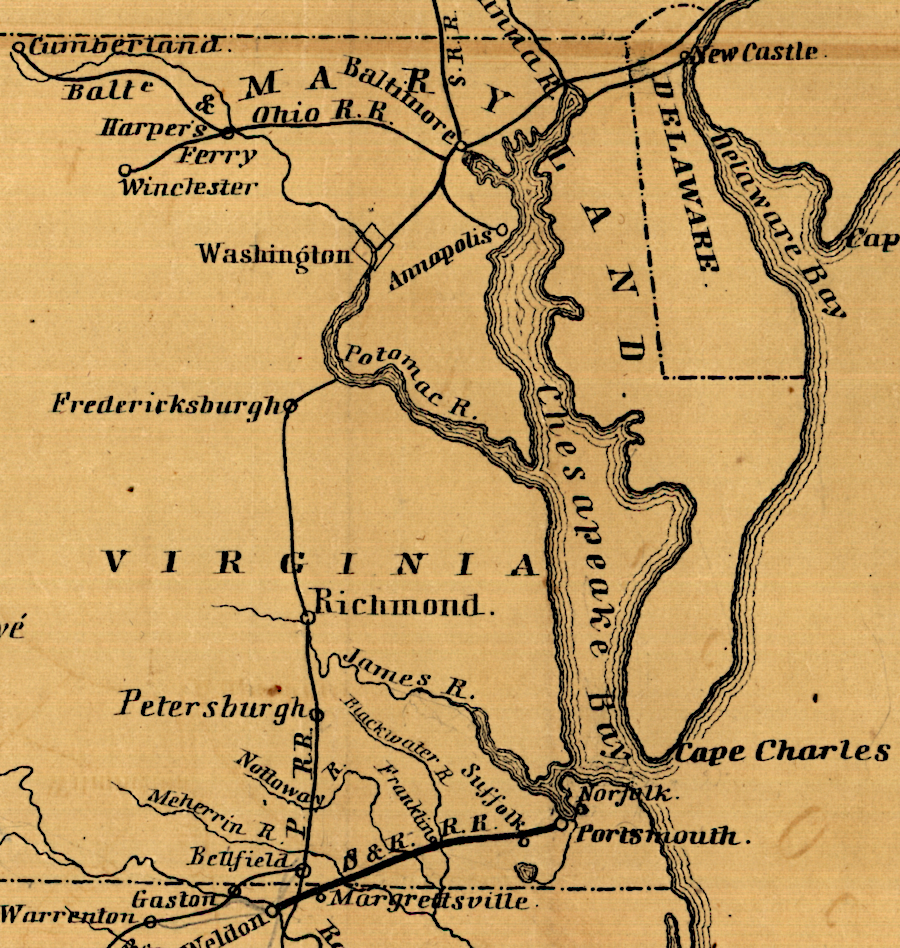

in 1847, Alexandria lacked any railroad connection to the hinterland

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Seaboard & Roanoke Railroad from Portsmouth, Va. to Weldon, N.C (by Ephraim W. Bouve, T. J Carter, 1847)

Almost as soon as Alexandria was "revested" back to Virginia in 1847, the General Assembly chartered the Orange and Alexandria (O&A) Railroad. By 1851, the Orange and Alexandria stretched southwest from the port city through the Piedmont to Gordonsville. It attracted the farm trade of the backcountry more effectively than the Warrenton Turnpike. To allow trains to get to the Potomac River waterfront, the Wilkes Street Tunnel was cut through the bluff between St Asaph's Street and Fairfax Street.

the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad connected Alexandria to its "hinterland" in the Piedmont

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos

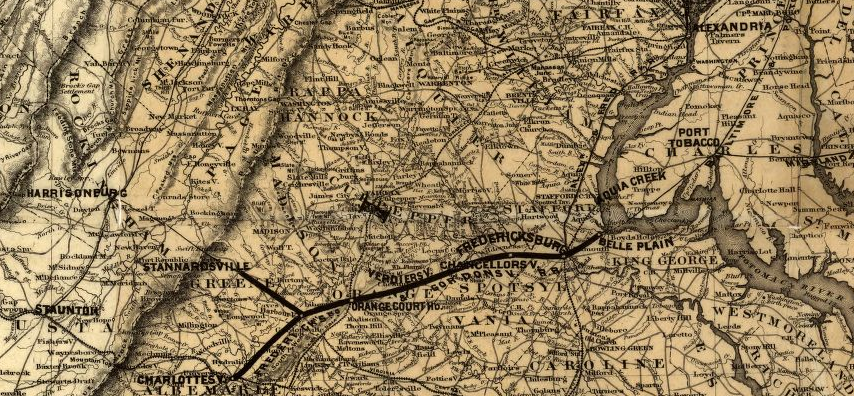

With the O&A Railroad, Alexandria out-competed Fredericksburg's merchants. Fredericksburg tried to attract trade from the Piedmont farms by building a canal up the Rappahannock River, bypassing various rapids and allowing reliable transportation despite high/low water levels. However, the canal arrived after the railroad. By the time the Rappahannock Canal connected the Fall Line at Fredericksburg to Kellys Ford (near present-day Remington in Fauquier County), farmers in Orange, Culpeper, and Fauquier counties were already accustomed to shipping via the O&A Railroad to Alexandria.

at the start of the Civil War, Alexandria was the dominant port city on the Potomac River with road, rail, and canal links into the hinterland

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia by Herman Boye (1826), updated by Lewis von Buchholtz (1859)

In the "first to market" competition, Alexandria won. Fredericksburg did not become the preferred business center of the Piedmont, even where it was physically closer, because farmers in the Rappahannock River Valley grew accustomed to shipping goods via roads and railroads to Alexandria.

Fredericksburg was linked to the Potomac River and to Richmond by one of the first railroads in the state, but did not build a line west to Orange/Culpeper counties before the Civil War. Some grading was completed on the route of the planned Fredericksburg and Gordonsville Railroad, but it was an "unfinished railroad" during the war.

the planned Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road was partially graded but had no rails to carry traffic during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the war of the Rebellion, Fredericksburg; Buzzard Roost; Dry Fork Creek; Dead Buffalo Lake; Big Mound (Plate XXXIII)

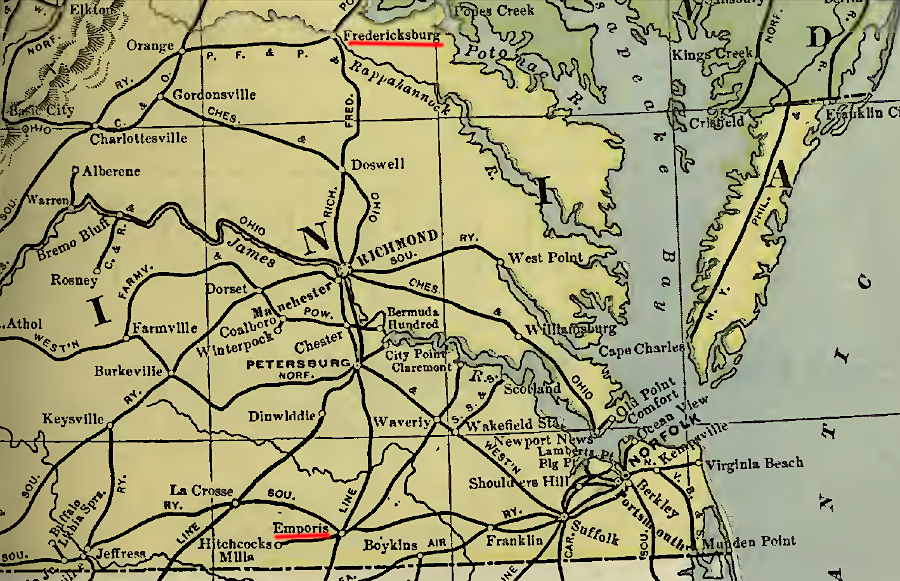

By the time Fredericksburg constructed the narrow-gauge Potomac, Fredericksburg & Piedmont (PF&P) in the 1870's, the economy of the Piedmont was tied tightly to Alexandria. The derogatory term "Poor Folks & Preachers Railroad" indicates that the PF&P was never a major freight route.4

the planned Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road was finally built as the narrow-gauge Potomac, Fredericksburg & Piedmont (PF&P) after the Civil War, but was unable to compete with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and became known as the "Poor Folks & Preachers Railroad"

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia (1869)

in 1901, Emporia had more railroad connections than Fredericksburg

Source: Poors Manual of Railroads 1901, Railroad Map of the United States - Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia (after p.128)

Alexandria was not satisfied with just the trade from the Piedmont. The city's ambitions extended further west to the Shenandoah Valley and beyond.

Baltimore had obtained the business from the Potomac River watershed, by out-competing the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) canal and constructing the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. The city also took advantage of its deepwater port to attract the modern steamships. Baltimore benefitted from traffic that used the Winchester and Potomac Railroad connection linking Winchester to Harpers Ferry, but the Maryland-based investors focused on linking up to the Ohio River and getting traffic from across the Appalachian Mountains. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad did not expand its network south of Winchester until after the Civil War, and Alexandria took advantage of the opportunity in the 1850's to capture the trade from south of Winchester.

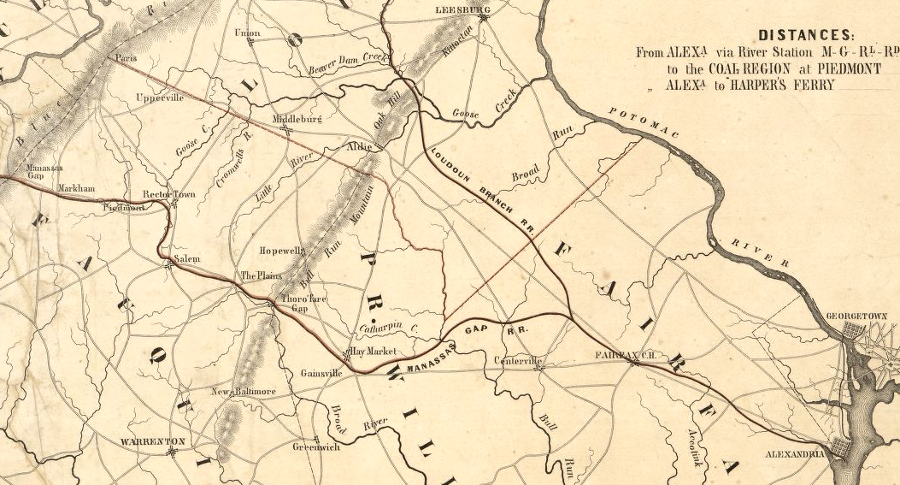

A charter for the Manassas Gap Railroad authorized an independent line to run from Mount Jackson to Alexandria, with a branch reaching into southern Loudoun County between the Blue Ridge and the Potomac River.

the Manassas Gap Railroad proposed a branch through Loudoun County, but that potential competitor to the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad was never built

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions; September, 1855

After the recession known as the Panic of 1857, construction of the Manassas Gap railroad was truncated. The independent line was connected to the O&A at a location named Manassas Junction, a name soon shortened to just "Manassas," and the branch into Loudoun County was never built.

The Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire railroad (AL&H) was expected to bring coal traffic from Hampshire County (now in West Virginia) to Alexandria, in addition to the farm trade from the Winchester area. The last part of the AL&H route was abandoned in the 1960's after construction of Dulles Airport, and the route is now the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) bike path. The AL&H was never built across the physical barrier of the Blue Ridge beyond Bluemont, and the modern bike trail stops in Purcellville.

ships at Alexandria waterfront, 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Quartermaster's Wharf, Alexandria, Va

Though the Manassas Gap and AL&H railroads were not completed as planned, they demonstrate how Alexandria competed with Fredericksburg, the District of Columbia, and even Baltimore by building a better transportation system. Unlike Dumfries and Fredericksburg, Alexandria connected its international port with the "hinterland," the surrounding region capable of supplying goods and purchasing items from the central city.

rail lines connecting to Alexandria in 1878: Alexandria and Washington Railroad crossing Potomac River, the Washington and Ohio (previously the AL&H, later the W&OD) stretching to Purcellville in Loudoun County, and the old Orange and Alexandria Railroad leading to Manassas

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins, 1878)

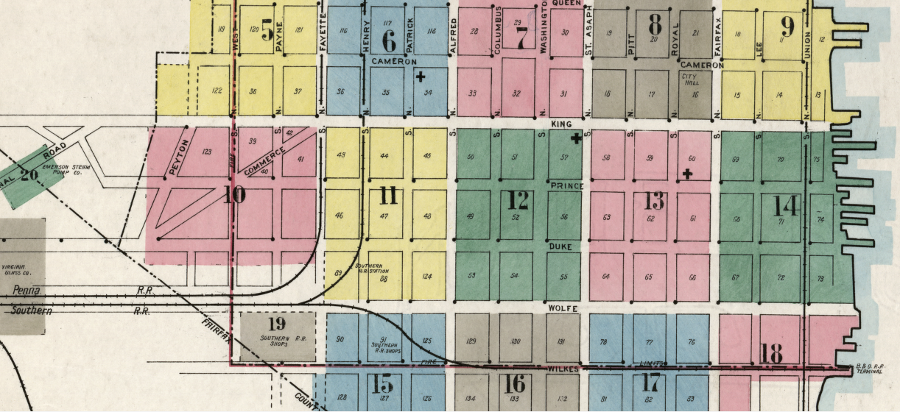

in 1912, the Pennsylvania Railroad used Fayette Street while the Southern Railway (which serviced the waterfront of Alexandria) had a parallel route a block away

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Alexandria, Independent Cities, Virginia

the first railroad bridge connecting Alexandria with Washington was built over Long Bridge during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Long Bridge (between 1860-70)

Alexandria won the shipping competition with Fredericksburg, Dumfries, and Georgetown, but lost the most valuable backcountry trade to Baltimore. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad reached Harpers Ferry and completed the Winchester and Potomac Railroad in 1836. That railroad diverted the northern (lower) Shenandoah Valley trade away from Alexandria to the port of Baltimore.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached the coal fields of Cumberland, Maryland in 1842, directing that freight to the Maryland port rather than to Alexandria. The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal did not begin to carry coal to Alexandria until 1850.

Alexandria continued to ship products using slave labor, but without adding value through processing or manufacturing in the city. Baltimore relied upon free white men to work in factories, and that city expanded as an industrial town as well as a shipping center.

Alexandria no longer serves now as a major port handling shipments inland to the western frontier; just tourist boats dock at its wharf today. The ferry that used to carry Baltimore and Ohio Railroad cars across the Potomac River was replaced by the Washington and Alexandria Railroad Bridge in 1863. That bridge was later removed, and the boxcar ferry is no longer operational. The waterfront next to the Wilkes Street tunnel originally completed by the Orange & Alexandria Railroad in 1856 has been converted from industrial to residential use.5

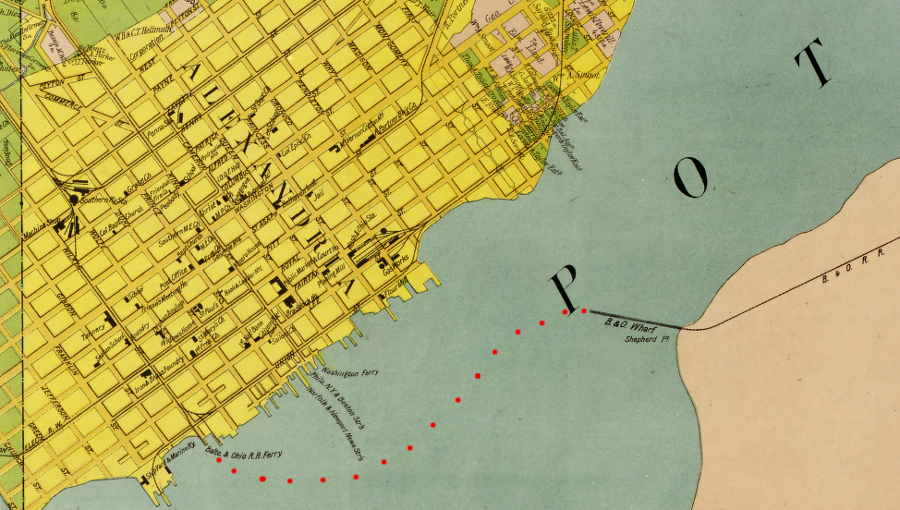

Multiple railroads served Alexandria. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had direct access to the city during the Civil War, hauling cars across the government bridge over the Potomac River. In 1870, the Pennsylvania Railroad ended its rival's monopoly of rail traffic into Virginia, and got the government to grant it exclusive rights to use the Long Bridge. To maintain its link, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built a 12.5 mile spur line from Hyattsville, Maryland through the District of Columbia to Shepherds Landing on the shoreline of the Potomac River.

From 1874-1906, the railroad used the Alexandria Branch to reach the river and carfloats to carry freight across the Potomac to Alexandria. That inefficient process ended in 1906, when the different railroads opened Potomac Yard and interchanged traffic there.

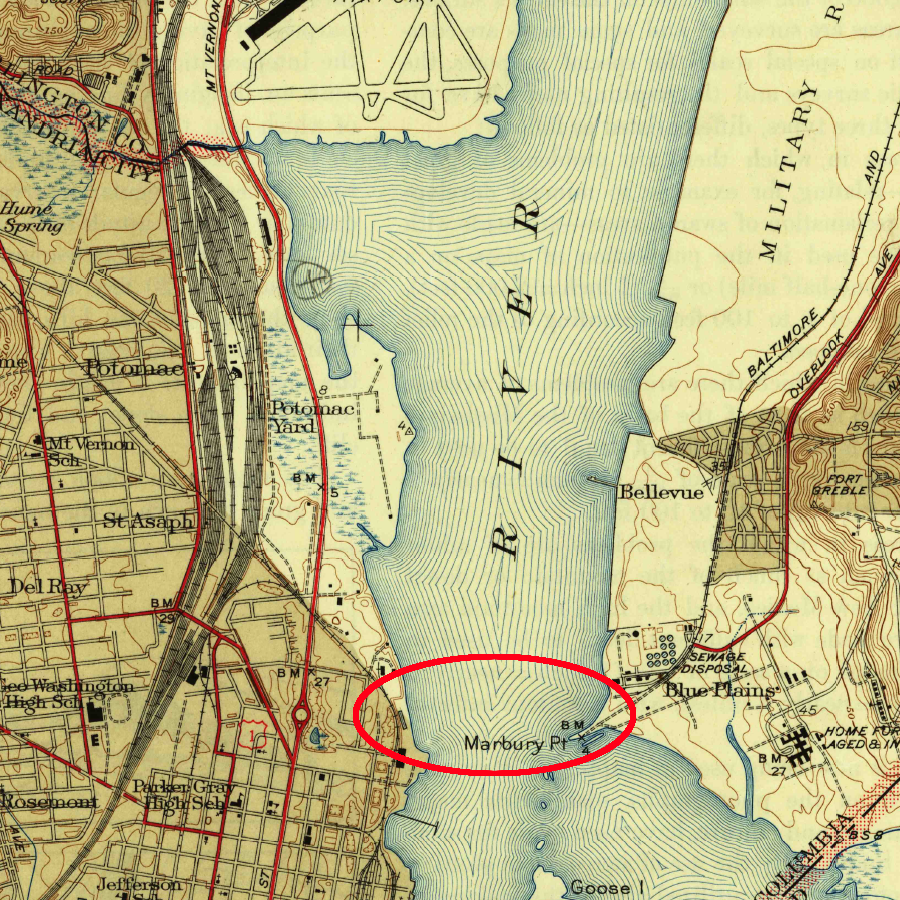

An "Emergency Bridge" was constructed in 1942 to handle the extra troop traffic in World War II, and to provide continuity of operations if the Long Bridge was made unusable by accident or saboteurs. It stretched 3,360 feet from the District of Columbia to Alexandria's shoreline at Third Street, next to Potomac Yard. That bridge was used between November 1942-1945, and was demolished in 1947.6

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad ferried freight cars across the Potomac River to a wharf on the Alexandria waterfront

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia for the Virginia Title Co. (1900)

the Emergency Bridge, which carried trains between Potomac Yard and the District of Columbia between 1942-1945, was not recorded on the 1945 topographic map

Source: US Geological Survey, Alexandria, VA 1:31,680 scale topographic quadrangle (1945)

The Alexandria merchants still rely upon "internal improvements" to connect Northern Virginia to external factories and markets, but many goods arrive in town on trucks that use interstate highways.

When the Washington Post started shipping newsprint by rail instead of ship to its Robinson Terminal several years ago, Alexandria lost its last major freight operation. The coal-fired power plant generating electricity in Alexandria was supplied by train until the facility, known originally as the Potomac River Generating Station, was closed by GenOn Energy in 2012.

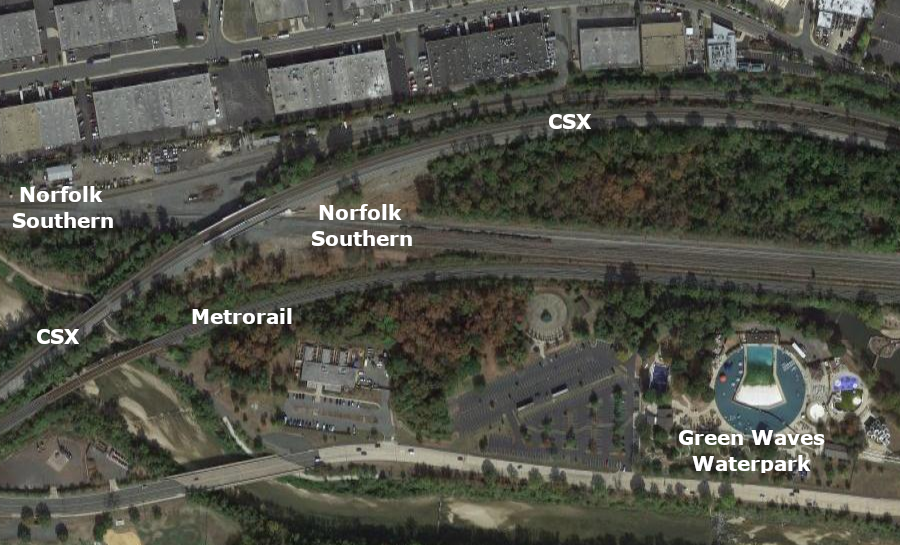

Two major railroads (the modern CSX) and the modern Norfolk Southern (incorporating the historic Orange and Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads) connect the Ohio River valley with various cities on the Eastern seaboard. Those railroads deliver goods from the interior of North America to ocean-going ships at the ports of New York/New Jersey, Baltimore, Newport News, and Norfolk - but not Alexandria. The city is no longer dependent upon railroads, turnpikes, or canals to transport raw materials to urban factories or to ship manufactured products to rural customers.

west of AF interlocking in Eisenhower Valley, Norfolk Southern uses the old Orange and Alexandria route and CSX uses the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad route

Source: GoogleMaps

Today, Alexandria's transportation network is designed to facilitate moving passengers by car and by three rail systems. Amtrak provides long-distance travel, Virginia Railway Express services commuters from Northern Virginia, and Metrorail provides local service.

in the six decades before the Civil War, Alexandria constructed three railroad lines and a network of roads, including the Little River Turnpike, to enhance the value of the city's location as a deepwater port on the Potomac River

Source: National Archives, Map of the Washington and Alexandria Railroad and its Connections with the Baltimore and Ohio, Loudon and Hampshire, and Orange and Alexandria Railroads

the Wilkes Street Tunnel was built by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in 1856

Source: Library of Congress, Orange & Alexandria Railroad, Wilkes Street Tunnel, Wilkes Street vicinity, Alexandria, Independent City, VA

Alexandria Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the counties of Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia / compiled and published from actual surveys by G.M. Hopkins by Charles Magnus

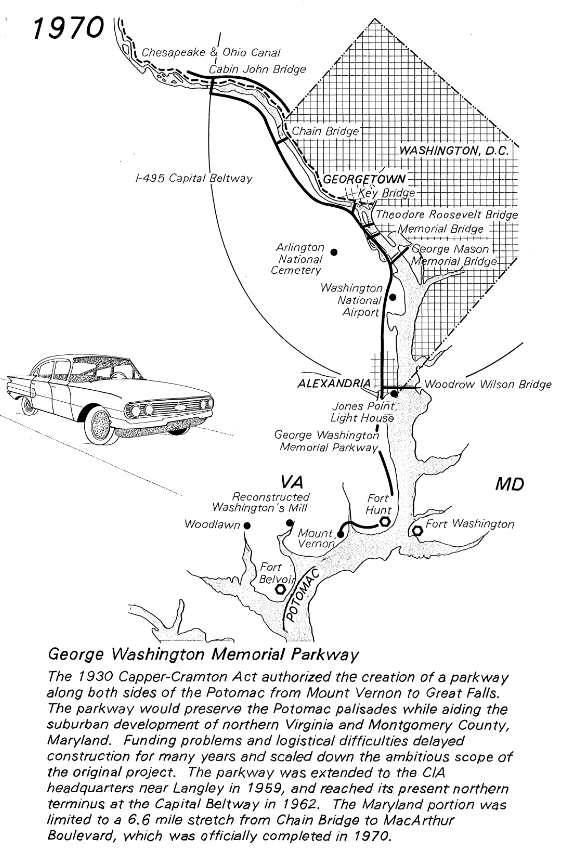

evolution of Alexandria's transportation and the George Washington Memorial Parkway

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record VA,30-____,8- (sheet 4 of 21) - George Washington Memorial Parkway, Along Potomac River from McLean to Mount Vernon, VA, Mount Vernon, Fairfax County, VA (by Anna Marconi-Betka, 1994)