The Indiana Company, Grand Ohio Company, and Vandalia

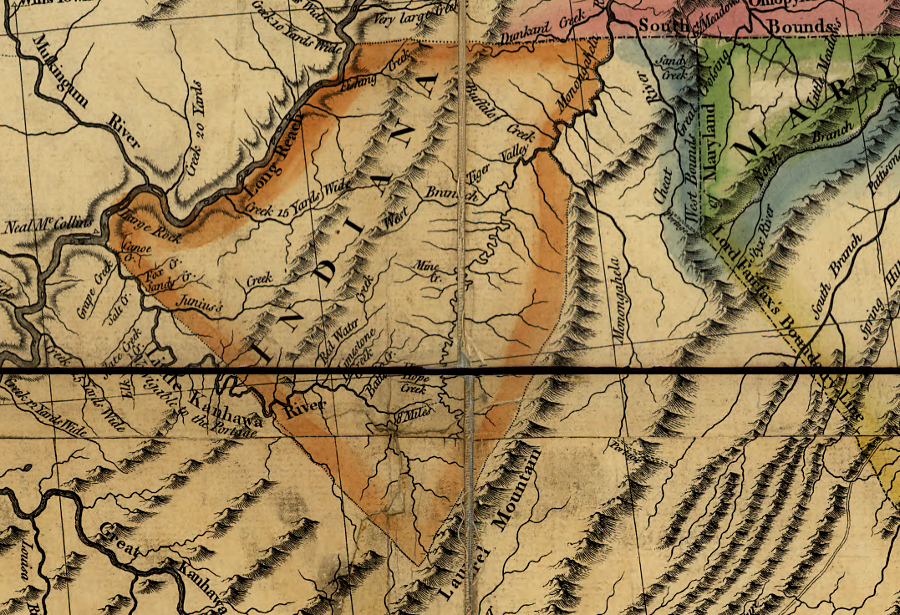

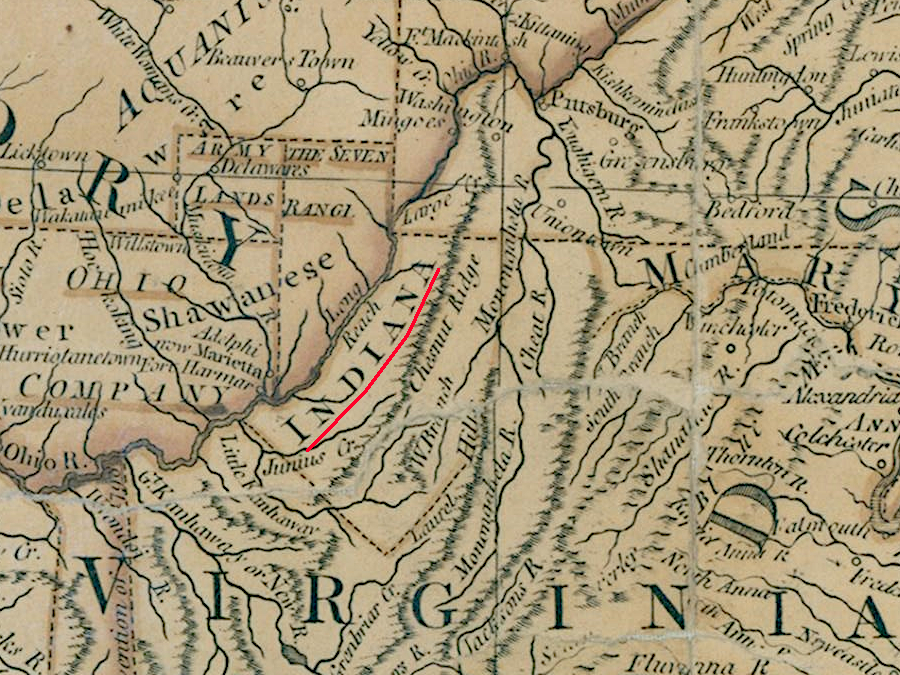

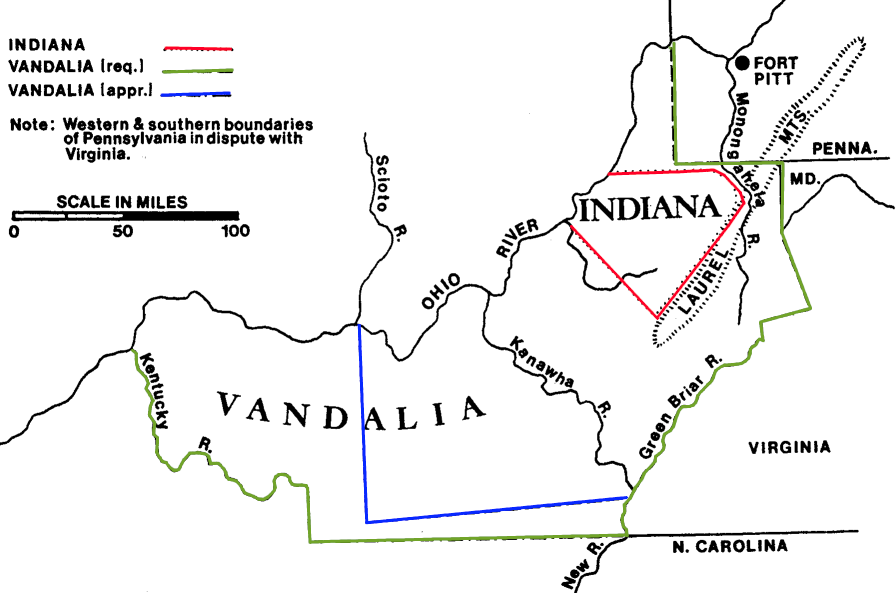

the "suffering traders" affected by Pontiac's War obtained the Indiana Grant as compensation

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the western parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina; comprehending the River Ohio, and all the rivers, which fall into it (Thomas Hutchins, 1778)

The start of the French and Indian War blocked the Greenbrier, Loyal, and Ohio companies and other land speculators from selling parcels from their grants in the Ohio River watershed.

Sale of western lands were frozen after the British victory when George III issued the Proclamation of 1763. That proclamation was a response to Pontiac's Rebellion, where Native Americans united to resist British occupation of the Northwest Territory. George III banned

George III's proclamation impacted the colonial leaders who had enough wealth and influence to invest in various land companies; they were unable to convert their claims into cash by surveying and selling parcels. In addition, veterans of he French and Indian War were affected. The Virginia colony was unable to award the land bounties that Governor Dinwiddie had promised to incentivize men to enlist in the Virginia Regiment.

After 1763, when colonial boundaries and authority to negotiate land deals with tribes were poorly defined, Philadelphia-based merchants and land speculators sought to obtain a grant for land south of the Ohio River. King George III had acquired title through defeat of the French, though in 1763 the Native American claims had not been resolved.

At the time no group was willing to pay the king for a large amount of land, then subdivide it through survey of individual parcels and recover the initial investment by later land sales. Buying the land required too much capital to be invested up-front.

However, if King George III would give (grant) a large chunk of land for free to a group of land speculators organized as a company, then they would survey and sell parcels. Counties could be organized with new settlers forming a militia for defense, and colonial officials could require settlers to pay quit rents (property taxes). Western land acquired from the French would finally generate some revenue, similar to the benefits of large grants made by Virginia officials in the 1730's to attract settlers into the Shenandoh Valley.

Pennsylvania-based traders, merchants, and land speculators organized the Indiana Company in 1764 and proposed a nearly 1,400,000 acre land grant. They ended up organizing the Grand Ohio Company and in 1770 requested royal approval of a 20,000,000 acre grant. It would create Vandalia, west of the Allegheny Front and south of the Ohio River.

At 1754 at the start of the French and Indian War, Native Americans and their French allies had seized goods shipped by various colonial traders to backcountry locations to exchange for furs. In 1763, traders again lost their goods (and in some cases, their lives) at the start of Pontiac's War.

The traders, and the merchants who had taken a financial risk by providing on credit items to sell, were engaged in a high-risk high-reward economic gamble. They suffered business losses at the start of two wars, but thought they might be compensated (indemnified) by the British government. The "suffering traders" claimed that by moving quickly into the lands ceded by France and initiating relationships with western tribes, they had been advancing British government interests.

Those affected in 1754 and in 1763, in some cases the same people, were initially united in their appeal. The assembled in Philadelphia and agreed to finance a trip to London by George Croghan, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District.

He was already planning to sail across the Atlantic Ocean in hopes of getting royal approval of a special deal he had negotiated in 1749 with the Haudenosaunee. The Native Americans had agreed to give him 200,000 acres of land at the end of King George's War. In additional arrangements, Native Americans supposedly granted him 40,000 acres between the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers and 100,000 acres along the Youghiogheny River. These grants were confirmed by the Native Americans in 1752 during negotiations for the Treaty of Logstown.

Pennsylvania and New York officials were unwilling to confirm the private sale. Croghan decided to go "over the heads" of the royal governors and seek approval from London officials. Then he could start surveying and selling parcels to settlers willing to accept what he claimed as title to the land, and live in the backcountry despite the threat of being attaced.

In London, Croghan failed to get support for his personal 200,000 acre deal or for direct compensation as requested by the suffering traders. He found government officials more interested in advancing personal agendas and engaging in party politics, and only marginally willing to address public policy issues in the distant colonies. He also discovered that Parliament had already spent the revenue generated from selling French prize ships, so there was no source of funds to compensate the 1754 traders.

Starting in 1765, the traders took a different approach and requested a grant of western land as compensation. Samuel Wharton, essentially bankupted by the seizure of his trading goods in 1763, took a big gamble. He partnered with George Croghan, John Batnton, and George Morgan and, through his agent William Trent, acquired claims from most other "suffering traders."

William Johnson, Croghan's boss as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, supported the request for the 1763 traders but not for those who suffered losses in 1754. In Johnson's opinion, the French needed to be involved in compensating the 1754 traders - but he endorsed making the Native Americans provide land as compensation for the 1763 seizures. Johnson thought that would deter similar seizures in the future, if war broke out again in the western territory.1

With Johnson's support, traders who had lost goods in both years focused on getting compensated for their 1763 losses. Eventually a group of 23 men organized the Traders Company. When they acquired the claims of the smaller traders, no money was advanced. The Traders Company promised payment only if royal officials finally authorized the Indiana grant.

The Traders company was also known as the Indiana Company, and at times the land requested was called the Illinois grant. Some of the Philadephia merchants had gambled again in 1764 and sent more goods west to sell to Native Americans on the Illinois River, but failed to recover the costs of that additional investment. The financial stress made them - and their creditors - even more anxious to get compensation for the 1763 losses.

To obtain political influence leading to Privy Council authorization for the nearly 1,400,000 acre Indiana land grant, company shares were given to the royal governor of New Jersey. Governor William Franklin was the son of Benjamin Franklin, and he helped finance the 1769 trip of William Trent and Samuel Whaton to lobby for the award of a land grant as compensation.

Benjamin Franklin had been in London since 1764. He had returned as the agent for the Pennsylvania Assembly, after serving in that role between 1757-1762. Benjamin Franklin advocated for the Indiana Company and its successors until 1774 as a matter of family interest. He was probably the best-connected colonial lobbyist in London; recruiting William Franklin was a wise investment by the Whartons.2

Ben Franklin described the new strategy of seeking land from the Native Americans rather than a royal grant in a 1763 letter:3

- When the last Peace was made, the Indians invited our Merchants to send Goods into their Country, promising all Safety and Protection to the Traders and their Effects. In full Reliance on those Promises, great Quantities of Goods were accordingly sent among them; when they perfidiously broke the Peace, without making the least Complaint of any Injury receiv'd, or demanding Satisfaction for any pretended to be receiv'd, seiz'd the Goods and massacred the Traders in cold Blood.

- It will appear reasonable to all, that if a Peace is granted to them, they ought to make all the Restitution and Satisfaction in their Power: But the Goods are consum'd, and they have no Money. And yet, if they are allow'd to enjoy the whole Benefit of their Villany, without suffering any Inconvenience, they will more readily repeat it the first Opportunity. It is therefore my Opinion, that they should always on such Occasions be obliged to give up some Part of their Territory most convenient for our Settlement, which might be apply'd to the Indemnification of the Merchants.

As Superintendent for Indian Affairs for the Northern Department, Johnson mixed his official responsibilities in negotiations with western tribes with his private agenda as a supporter (and possibly as an investor) for the Indiana Company. He arranged a 1765 meeting with a group of Haudenosaunee chiefs at his mansion in the Mohawk River Valley in New York, Johnson Hall.

At that gathering, the chiefs agreed to transfer land and clear the complaints of the suffering traders from 1754 as well as 1763. However, Johnson limited his support to those who lost property in 1763, when there was peace in North America.

The Proclamation of 1763 was still a barrier. If the boundary remained the Eastern Continental Divide, there would be no value for the Indiana Company in obtaining rights to lands in the Ohio River valley west of the Proclamation LIne. To get the Haudenosaunee and Cherokee to agree to move the line and allow additional settlement of the western lands, land speculators (including the Indiana Company) had to get British officials to provide expensive presents.

The problem was addressed by pressuring officials in London to agree to move the proclamation line, and to get the Haudenosaunee to agree to specific land grants as part of a deal. As Superintendent for Indian Affairs for the Northern Department, William Johnson led the British side of the negotiations in October-November 1768 to purchase land and allow gradual settlement which the Haudenosaunee would accept.

In the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, Johnson ensured the Haudenosaunee concurred with the 200,000 acre grant to George Croghan, a 3,500,000 acre grant to the Indiana Company, and the 200,000 acres promised by Governor Dinwiddie to those who enlisted in the French and Indian War. Those grants were to be carved out of the extensive territory ceded to the British in the Fort Stanwix treaty.

William Johnson arranged it so the entire treaty was conditioned on the acceptance by the British government of the "side deals." That increased the number of advocates who would pressure the Privy Council to approve the treaty, while limiting the ability of London officials to modify its terms.

The Indiana Company tactic of getting land rights incorporated in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix negotiations was based in part on the fixed location of Pennsylvania's western boundary. Though the colony's exact western edge was still undefined at the time (it was not settled until 1784), everyone knew that Penn's grant limited the width of his colony to five degrees of longitude.

Unlike Virginia, Pennsylvania did not have western land claims extending to the Mississippi River. Unlike colonial officials in Williamsburg, colonial officials in Philadelphia had few options for rewarding influential men with western land. Pennsylvanial officials had little to offer to the Philadelphia merchants seeking compensation for the suffering traders. In contrast, royal officials had unlimited authority to negotiate deals for western lands which would compensate the investors/suffering traders. The boundaries defined in the 1612 charter of Virginia or the 1682 charter of Pennsylvania were not constraints; the line of authorized settlement to be moved was defined by the Proclamation of 1763.

Dr. Thomas Walker was the Virginia colony's representative and signed the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix. He was a member of the Loyal Land Company, with a claim dating back to 1749 to 800,000 acres in the territory west of the 1763 Proclamation Line. The company has 200,000 acres of land already sold or surveyed, mostly in the Holston River and Clinch River valleys. The 1768 treaty made no provision for the Loyal Land Company, but Walker may have decided that the overall cession by the Haudenosaunee was the best deal he could obtain.

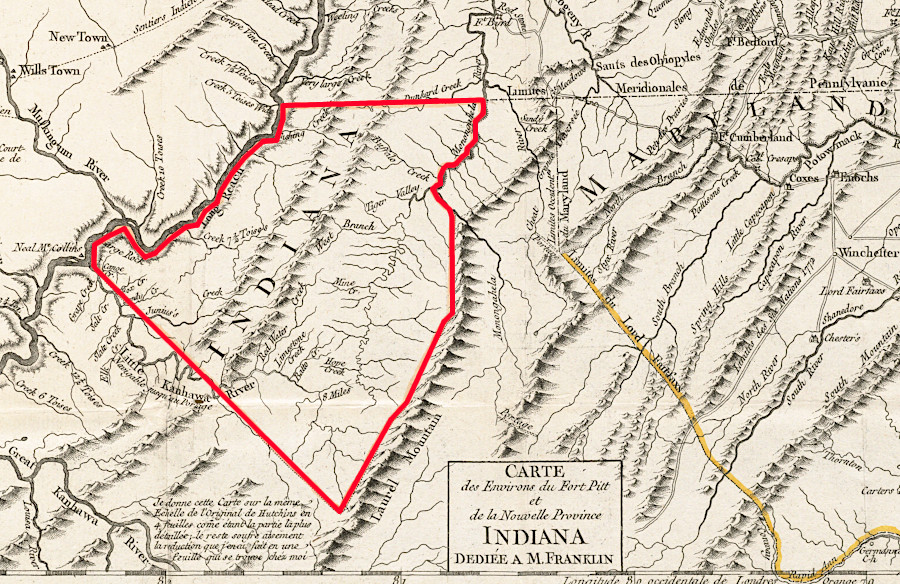

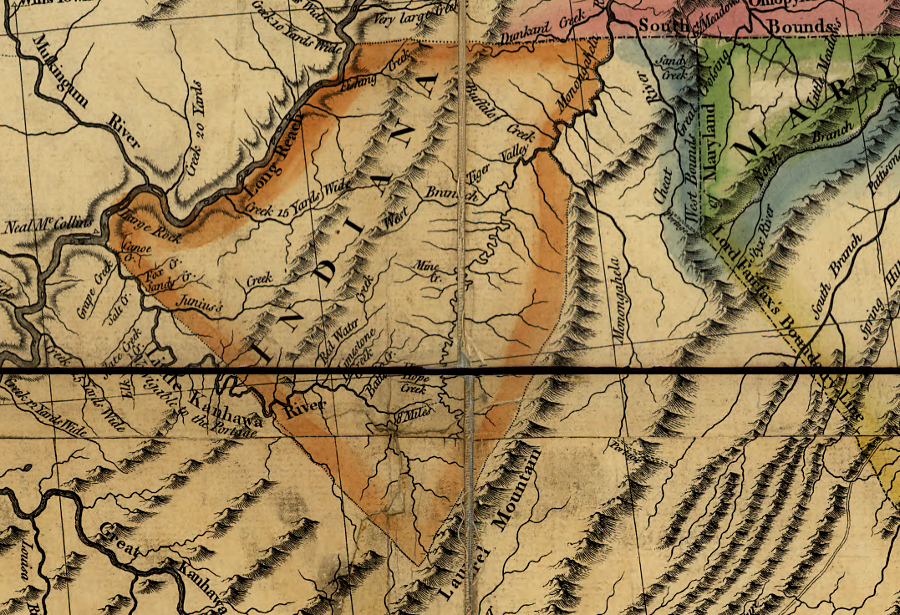

In an agreement signed two days before the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, a chunk of land was carved out for the Indiana Company. The boundaries of the 3,500,000 acre Indiana Company tract extended from the:4

- ...southerly side of the mouth of Little Kenhawa Creek, where it empties into the river Ohio, and running from thence south east to the Laurel Hill, thence along the Laurel Hill until it strikes the river Monogehela... to the Southern boundary line of... Pennsylvania, thence westerly... to the river Ohio, thence down the said river... to the place of beginning.

In the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the British acquired title to lands south of the Ohio River extending to the mouth of the Tennessee River from the Haudenosaunee. They negotiated terms for the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes and others who occupied the Ohio Country. The Haudenosaunee claimed they were the landowners due to previous conquest of the other tribes, and had exclusive rights to speak for all the Native Americans at the treaty negotiations.

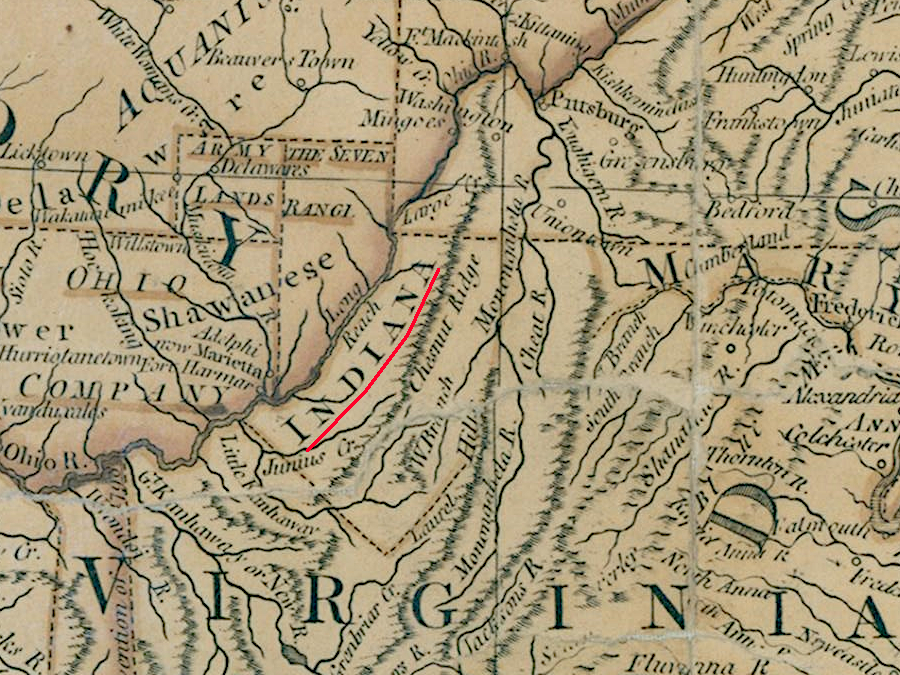

in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois agreed to compensate the "suffering traders" with land to be called Indiana

Source: Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center, Carte des environs du Fort Pitt et de la nouvelle province Indiana (Thomas Hutchins, 1781)

The tribes living north of the Ohio River who hunted in Kentucky were forced to be silent at Fort Stanwix. They had to accept the deal while observing negotiations at Fort Stanwix, but later joined in Pontiac's Rebellion and killed intruding settlers.

By design the Cherokee were not involved in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The Cherokee and Haudenosaunee had agreed to a treaty in February 1768. The Cherokee then made a separate arrangement with John Stuart, the Superintendent for Indian Affairs for the Southern Department, before the northern tribes met at Fort Stanwix.

In the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor, the Cherokee ceded their claims south of the Ohio River and west to the mouth of the Kanawha River. That cession included the 2,000,000 acres sought by the Indiana Company and the overlapping 2,500,000 acres sought by the rival Mississippi Company, as well as land claimed since 1749 by the Loyal Land Company and the Ohio Company. Arthur Lee was the champion in London for the Mississippi Company. He justified its request by using the need to provide land in Kentucky for veterans of the French and Indian War.

To get royal confirmation of the Indiana Company's deal in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, Samuel Wharton and William Trent sailed to London in 1769. British officials there were angry that William Johnson had exceeded his instructions in negotiating the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, and initially declined to confirm the treaty.

Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Southern Colonies and a member of the Board of Trade, was especially opposed. He objected to William Johnson exceeding the royal direction and acquiring excessive lands to the west, and mixing the conformation of private land claims into the official adoption of the public treaty.

Authorizing more settlement west of the Proclamation Line of 1763 was bad policy, according to LOrd Hillsborough. Increasing the number of colonists moving into Native American homelands would create the unnecessary risk of triggering another war like Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763.5

Johnson had been authorized in his treaty negotiations to move the proclamation line, the barrier to colonial settlement, westward to the mouth of the Kanawha River. That expansion would have added about 150 miles of lands stretching to the west.

However, at Fort Stanwix Johnson arranged for the Haudenosaunee to authorize colonial settlement not just to the Kanawha River, but for an additional 350 miles further to the west. In the 1768 treaty, the Haudenosaunee relinquished their rights to all the land south of the Ohio River stretching westward (downstream) to the mouth of the Tennessee River. That was just 30 miles east of the Mississippi River.

The Privy Council resolved its internal differences and did approve the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in late 1769, but Samuel Wharton and William Trent were unable to get approval of the separate Haudenosaunee sale to the Indiana Company.

To improve their ability to lobby key officials in London, the Indiana Company joined forces with Thomas Walpole and additional allies in England. Thomas Walpole was well-connected as the nephew of Sir Robert Walpole, who had established the role of Prime Minister in Great Britain.

The additional investors ("proprietors") joined forces on December 27, 1769 and formed the Grand Ohio Company. It was also called the Walpole Company, and later the Vandalia Company. Benjamin Franklin was a member, and used his influence in London to seek approval of a land grant that violated the Proclamation of 1763.

Some of the original claimants to the Indiana grant agreed to stop lobbying for their grant. Getting title to some of the western land as part of the Grand Ohio Company would be better than retaining 100% of the Indiana Company claim, which no British official in London appeared willing to authorize. Samual Wharton and William Trent ensured they held shares in the Grand Ohio Company. Other Indiana Company investors who were still back in Pennsylvania were cut out of the deal.

The Grand Ohio Company asked for a royal charter for a brand new colony south of the Ohio River. The original request was for 2,500,000 acres. The Earl of Hillsborough, who was Secretary of State for the Colonies, supported a strict interpretation of the Proclamation of 1763 and objected to western settlement. He told the Grand Ohio Company investors to aim higher, and they expanded the request and sought a 20,000,000 acre grant.

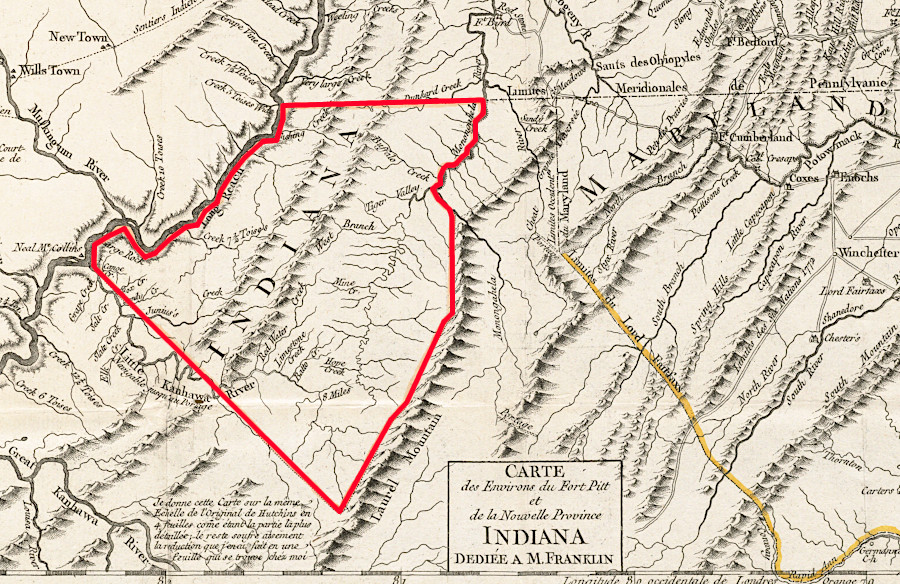

The expanded request would encompass all the land south of the Ohio River stretching from where the river crossed the Pennsylvania boundar (somewhere near Fort Pitt) to the mouth of the Scioto River to Cumberland Gap, then north on the ridgeline of Cumberland Mountain to the confluence of the New and Greenbrier rivers (headwaters of the Kanawha River), east to the beginning of the Greenbrier River, then north along the Allegheny Front to Maryland's western boundary, then along Pennsylvania's western boundary to the Ohio River.

George Washington expected that the Grand Ohio Company would get 80% of the land Virginia had arranged for the Cherokee to cede in the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor and the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. The grant would include all of modern-day West Virginia and about 1/3 of Kentucky.

Hillsborough made the suggestion because he thought such a massive request would have lower probability of approval by the Privy Council; he was trying to block royal approval of the land grant rather than trying to reward the Wharton syndicate by expanding the acreage. The Grand Ohio Company investors proposed acquiring more land than any previous land company had envisioned not because they were excessively land-hungry, but because Lord Hillsborough was trying to undercut their chance of success. To mobilize opposition, Lord Hillsbororoug wrote twice to Governor Botetourt in 1770 asking for Virginia's feedback on the Grand Ohio Company request.

The requested grant, at either 2.5 million acres or 20 million acres, would block the Ohio Company from surveying and selling its land. However, the Ohio Company lacked the political influence to overcome the Proclamation of 1763. Virginia officials had declined to endorse allowing the Ohio Company to start selling land, even though its grant had been awarded far earlier. The rival Grand Ohio Company was recognized as the only large land grant that would get approved in London.

On May 7, 1770 the Ohio Company claimants, losing hope that their 1749 grant for up to 500,000 acres in the Ohio River Valley would be honored, agreed to join the Grand Ohio Company. Acknowledging defeat, George Mercer withdrew the Ohio Company's request for Privy Council approval of the original 1748 grant.

To get competing land speculators to withdraw their proposal, the Grand Ohio Company gave the Ohio Company investors two of the 72 shares. The Walpoles had orginally proposed to George Mercer, the Ohio Company agent in London, that he could be given an additional share for his personal benefit and be made the first governor of the new colony. The Walpoles also agreed that the 200,000 acres promised by Governor Dinwiddie in 1754 would be reserved for French and Indian War veterans.

If what was called the Walpole Grant in London (and later the Vandalia Company) ended up awarding the investors 20,000,000 acres of land, then Ohio Company members would own 3% of the Grand Ohio Company. Two shares of the massive grant request would gain the Ohio Company investors slightly more than their original request for 500,000 acres.

The Privy Council eliminated one competitor by flatly rejecting the Mississippi Company's request for a 2,500,000 acre grant in 1770. Arthur Lee had championed that proposal, saying it would provide land for bounties promised to French and Indian War veterans.

As he had planned, Lord Hillsborough got the Board of Trade to oppose the oversized 20,000,000 acre request from the Grand Ohio Company. However, Benjamin Franklin then outmaneuvered the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Franklin convinced the Privy Council members that Native Americans would not oppose the land grant. He also argued that the colonists in the Mississippi River watershed would choose to ship their goods across the Appalachians rather than float down to New Orleans, which the Spanish controlled. Franklin recognized the desire or British merchants and Privy Council members to increase trade with seaports on the Atlantic Ocean, thus increasing business in England.

Major Trent and George Mercer spoke directly with the Privy Council at a June 24, 1772 meeting in the Palace of Whitehall. They indicated the colony's new capital would be at Fort Pitt, which the British army was abandoning in order to reduce costs in North America. The 20,000,000 acre proposal was approved officially on July 1.

Lord Hillsborough, upset at being out-lobbied by the American colonists and rejected by his peers, resigned on August 13, 1772. A day later, his replacement Lord Dartmouth sent the grant documents to the Solicitor General for final legal approval.

With the Vandalia grant, the Privy Council abandoned the policy established in the Proclamation of 1763 to constrain colonial settlement east of the Appalachians and minimize conflict with the Native American tribes living west of the mountains. Colonial governors had been directed to stop issuing land grants to individual settlers after the Proclamation of 1763, but British policy on control of trade and settlement in the western lands was inconsistent. By 1772, Fort Pitt and most other western bases had been abandoned. The colonial governments were burdened with managing negotiations with Native Americans who complained about settlers and traders, but the governors were not sent directions to authorize land patents.

The Privy Council also authorized the Georgia colony to sell the "New Purchase" lands acquired from the Cherokee by the 1773 Treaty of Augusta. That opened up 2,500,000 acres stretching to the Oconee and Altamaha Rivers. Officials in London, but not the king's appointees in the colonies, had the power to approve western settlement.

The Privy Council decision on the Walpole grant may have been affected by more than imperial concerns. The Grand Ohio Company had given shares to key decisionmakers; Privy Council members had a personal economic stake in their decision.

Having lost the policy argument, Lord Hillsborough resigned his position as Secretary of State for the Colonies.

The Walpoles renamed their Indiana proposal after Prime Minister William Pitt, another tactic to obtain official favor. The name "Pittsylvania" was dropped after Pitt lost power and the Walpoles chose the name "Vandalia" in 1773. That name honored the German heritage of King George and his wife Charlotte, who was supposedly descended from the Vandals.

Samuel Wharton anticipated being appointed governor of the new colony and living at Fort Pitt.6

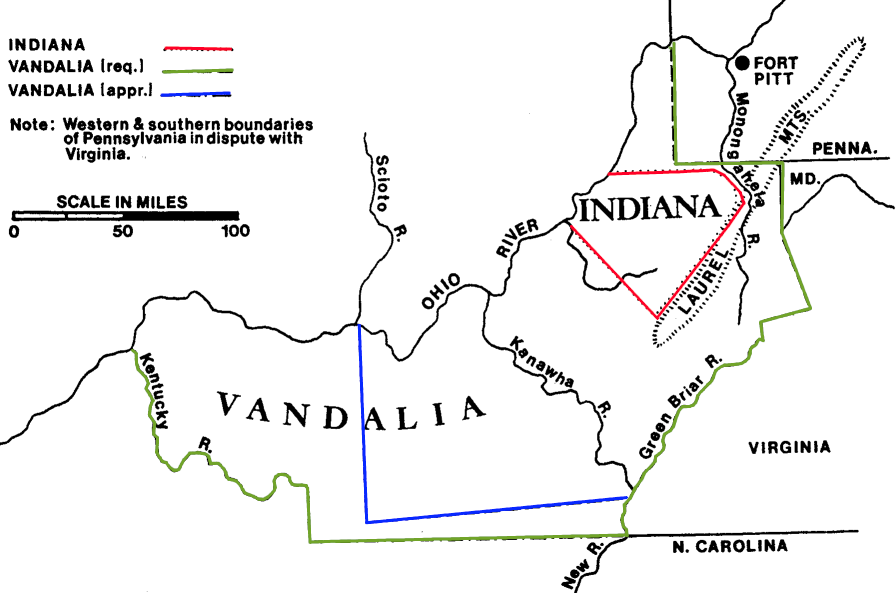

the "suffering traders" grant obtained in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix expanded by 1772 to the proposed 20,000,000 acre colony of Vandalia

Source: Wikipedia, Ohio Company

The investors in the Grand Ohio Company had succeeded. Because the Ohio Company chose to merge rather than compete, its investors ended up with two shares worth 556,000 acres. Investors who had backed other land companies and had not consolidated their claims with the Walpoles ended up with nothing.

British officials focused on American rebelliousness in 1774-1775. Formalizing the Vandalia colony with a new capital at Fort Pitt, so surveys of parcels could be completed and patents issued by colonial officials, was delayed as Parliament and King George III debated how to respond to the 1773 Boston Tea Party and strong colonial resistance to the Coercive Acts as the colonists became insurrectionists, rebels, and eventually revolutionaries.

Many British officials saw few benefits from creating Vandalia. Communities of land-hungry settlers west of the mountains would have little desire to obey royal policies. The Superintendents for Indian Affairs in both the Northern Department and the Southern Department were struggling to create reliable alliances with Native Americans. Authorizing colonists to intrude into western lands would have been counter-productive.

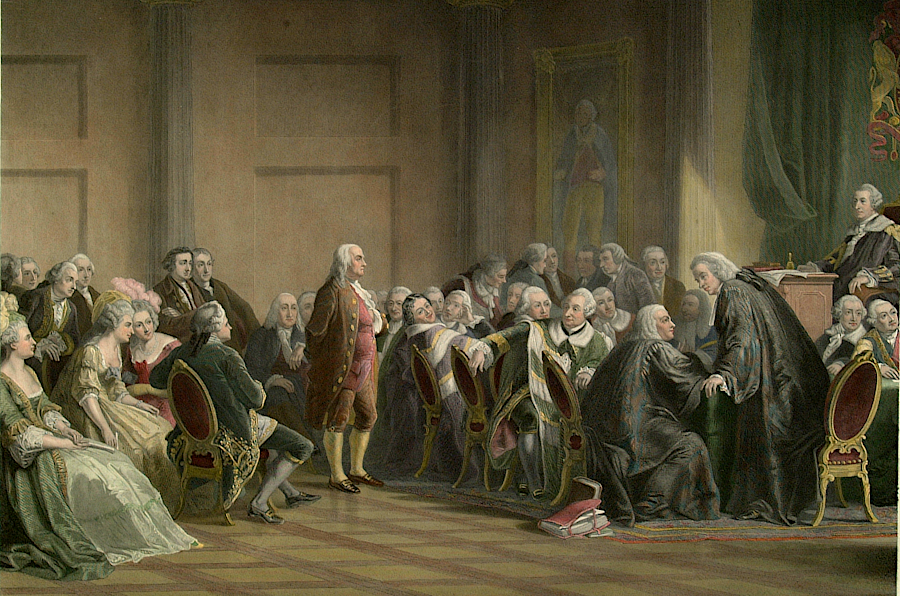

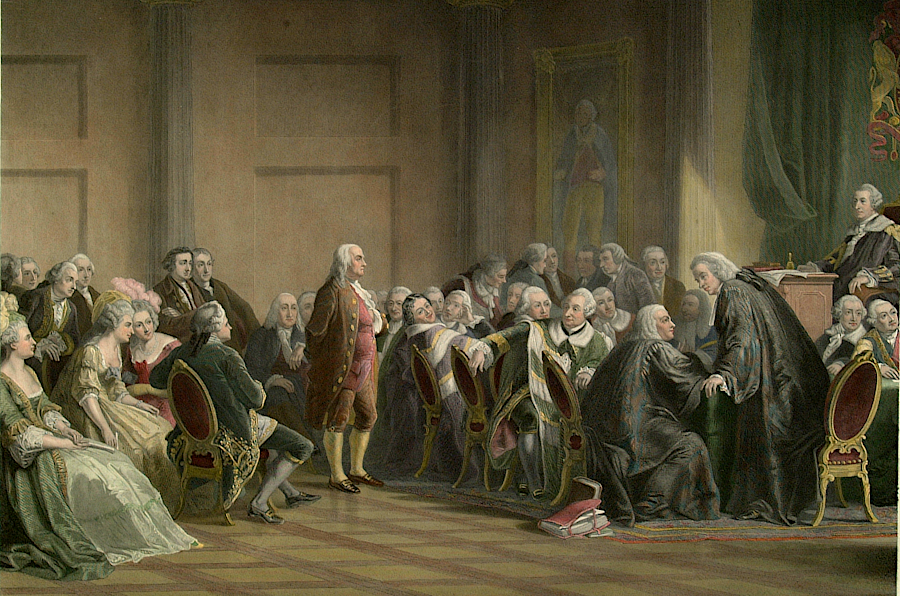

Benjamin Franklin created a major problem for the Grand Ohio Company when he was caught releasing private letters of the royal governor in Massachusetts which colonists had intercepted. That breach of honor led to Franklin being forced to endure a one-hour diatribe at the Privy Council delivered by Alexander Wedderburn on January 29, 1774. The anger of top British officials may have been exacerbated by Franklin's publication in 1773 of his acerbic "Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One" satire.

Wedderburn was also the Solicitor General who had to complete the final steps required to formalize the Privy Council decision to approve the Grand Ohio Company grant. He had received the Vandalia paperwork from Lord Dartmouth six months earlier.

Despite his anger at the company's representative, Benjamin Franklin, Wedderburn finally signed the necessary documents to authorize the Vandalia grant on May 1, 1775. However, creation of the 14th colony of Vandalia was suspended until the unrest in North America could be resolved. Soon afterwards, news arrived in London of the fighting at Lexington and Concord.

the Privy Council confronted Benjamin Franklin on January 29, 1774 for his support of rebellious Massachusetts, and the 20,000,000 acre grant for Vandalia was never finalized

Source: American Philosophical Society Library, Franklin before the Lords in Council, 1774

In 1775 William Trent tried "Plan B," seeking approval of the grant from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He narrowed the request to acquisition of the just the original 2,500,000 Indiana parcel. Despite offering shares of the Indiana Company as a bribe to eight delegates, Trent could not overcome the steady opposition by the influential Virginia delegation in the Continental Congress.

The Indiana Company reorganized, including the original investors, on March 20, 1776 in Philadelphia. Recognizing that a grant from British officials would no longer be valid, they continued to pressure the Continental Congress to formalize their rights to the original Indiana grant made by the Haudenosaunee to the "suffering traders" during negotiations for the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix.

Delegates to the Continental Congress also were pressured by other land companies. There were competing claims to western lands, and separate colonies claimed overlapping authority over the Ohio River watershed. Continental Congress delegates also knew that the western lands could be used for land bounties that incentivized men to enlist in the Continental Army, and that those lands could be sold to generate revenue for the new national government.

Later in the 1780's, Samuel Wharton used his position in the Continental Congress to seek some sort of land grant based on the claims of the suffering traders. That effort also failed.

The authority of the newly-independent states to authorize western land sales and grants was not resolved until 1784. Virginia ceded its claim to the Northwest Territory, and the new national government ended up as the final authority. The Virginia cession made no provision for the various land companies with claims dating back to 1749, though the state did reserve territory for its military veterans and ensured early settlers could obtain ownership of preemptive claims.

Land speculators failed to get the new United States of America to approve the Vandalia, Ohio Company, or other grants. Instead, military reserves were created to satisfy the land bounties promised to veterans. The Northwest Territory was surveyed and the national government created a land office to dispose of its new real estate.7

the proposed colony of Vandalia expanded far beyond the boundaries of the Indiana land claim

Source: Wikipedia, Ohio Company

George Croghan sold his share on the Indiana Company to two of the Wharton brothers at the end of 1768; he managed to generate some revenue from his claims. Suffering traders who sold their claims for cash to William Trent or the Walpoles also ended up benefitting from land speculation. The Illinois Company, Indiana Company, Mississippi Company, and Grand Ohio Company/Vandalia Company sold no land, so the investors who had funded years of lobbying efforts for those speculative ventures received no profits.8

as late as 1793 the Indiana land claim was still being recorded on British maps

Source: National Archives, United States of North America with the British Territories and Those of Spain According to the Treaty of 1784 (1793)

"Vandalia" remains on the map today as a county in West Virginia. In 1863, the western counties of Virginia created a new state separate from the Restored Government of Virginia. One name proposed for the new state was Vandalia, before final adoption of the name West Virginia.9

Links

References

1. Barbara Rasmussen, Absentee Landowning and Exploitation in West Virginia, 1760-1920, University Press of Kentucky, 2015, pp.24-26, https://books.google.com/books?id=CK4eBgAAQBAJ; "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), https://archive.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html; George E. Lewis, The Indiana company, 1763-1798; a study in eighteenth century frontier land speculation and business venture, 1941, pp.39-44, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000101098&seq=9; Peter Marshall, "Lord Hillsborough, Samuel Wharton and the Ohio Grant, 1769-1775," The English Historical Review, Volume 80, Number 317 (October, 1965), p.717, https://www.jstor.org/stable/559309; Edward G. Williams "Fort Pitt and the Revolution on the Western Frontier," The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 59, Number 1 (January 1956), pp.6-7, p.9, https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3389/3220

(last checked January 28, 2026)

2. "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), https://archive.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html; James D. Anderson, "Samuel Wharton and the Indians' Rights to Land: An Eighteenth-Century View," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 63 (April 1980), pp.123-126, https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3645; George E. Lewis, The Indiana company, 1763-1798; a study in eighteenth century frontier land speculation and business venture, 1941, pp.45-53, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000101098&seq=9; "Agent to London," Benjamin Franklin Historical Society, http://www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/agent-london/ (last checked December 7, 2025)

3. "From Benjamin Franklin to Richard Jackson, 24 December 1763," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-10-02-0220 (last checked September 4, 2025)

4. James D. Anderson, "Samuel Wharton and the Indians' Rights to Land: An Eighteenth-Century View," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 63 (April 1980), pp.127-131, https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3645; George E. Lewis, The Indiana company, 1763-1798; a study in eighteenth century frontier land speculation and business venture, 1941, pp.61-65, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000101098&seq=9 (last checked September 4, 2025)

5. "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), https://archive.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html; "1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/1768-boundary-line-treaty-of-fort-stanwix.htm; Jason A. Cherry, "Vandalia Colony: American Triumph or Folly?," Journal of the American Revolution, August 14, 2025, https://allthingsliberty.com/2025/08/vandalia-colony-american-triumph-or-folly/; Peter Marshall, "Lord Hillsborough, Samuel Wharton and the Ohio Grant, 1769-1775," The English Historical Review, Volume 80, Number 317 (October, 1965), pp.718-719, https://www.jstor.org/stable/559309 (last checked December 7, 2025)

6. Barbara Rasmussen, Absentee Landowning and Exploitation in West Virginia, 1760-1920, University Press of Kentucky, 2015, pp.24-26, https://books.google.com/books?id=CK4eBgAAQBAJ; "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), https://archive.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html; James D. Anderson, "Samuel Wharton and the Indians' Rights to Land: An Eighteenth-Century View," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 63 (April 1980), pp.132-137, https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3645; "Agreement to Admit the Ohio Company as Co-Purchasers with the Grand Ohio Company, 7 May 1770," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-17-02-0071; "The Founders and the Pursuit of Land," Lehrman Institute, https://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/founders-land.html; Jason A. Cherry," Vandalia Colony: American Triumph or Folly?," Journal of the American Revolution, August 14, 2025, https://allthingsliberty.com/2025/08/vandalia-colony-american-triumph-or-folly/; Stephen Carr Hampton, "On this date... June 1, 1773... Georgia," Memories of the People blog, June 1, 2014, https://memoriesofthepeople.blog/2014/06/01/on-this-date-june-1-1773-georgia/; "Jonathan Boucher to George Washington, 18 August 1770," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0247; "George Washington to Botetourt, 9 September 1770, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0253; "George Washington to Botetourt, 5 October 1770," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0261 (last checked December 26, 2025)

7. James D. Anderson, "Samuel Wharton and the Indians' Rights to Land: An Eighteenth-Century View," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 63 (April 1980), pp.132-137, https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3645; "Editorial Note on the Reorganization of the Indiana Company, 19 January 1776 to 20 March 1776," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0197; Jason A. Cherry," Vandalia Colony: American Triumph or Folly?," Journal of the American Revolution, August 14, 2025, https://allthingsliberty.com/2025/08/vandalia-colony-american-triumph-or-folly/; Charles Greifenstein, "How Alexander Wedderburn Cost England America," American Philosophical Society, January 9, 2018, https://www.amphilsoc.org/blog/how-alexander-wedderburn-cost-england-america; "Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One, 11 September 1773," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0213 (last checked December 28, 2025)

8. "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), http://www.wvculture.org/HISTORY/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html (last checked August 16, 2016)

9. "What's in a name? The origin of 'West Virginia'... and what the state might have been called instead," West Virginia Tourism Office, https://wvtourism.com/whats-name-origin-west-virginia-state-might-called-instead/ (last checked June 22, 2019)

in the 1790's, the Federal government sold large parcels of the public land north of the Ohio River to land speculators

Source: Library of Congress, The United States of North America, with the British territories (William Faden, 1793)

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places