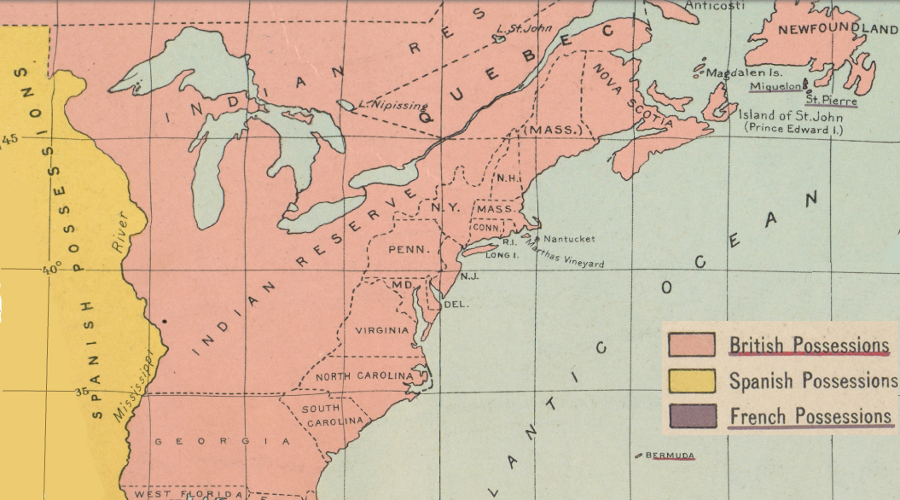

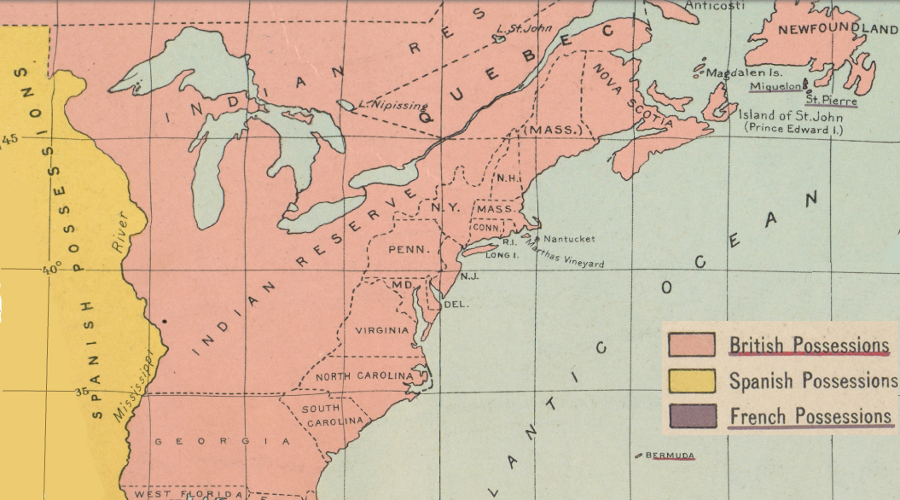

The Proclamation Line of 1763

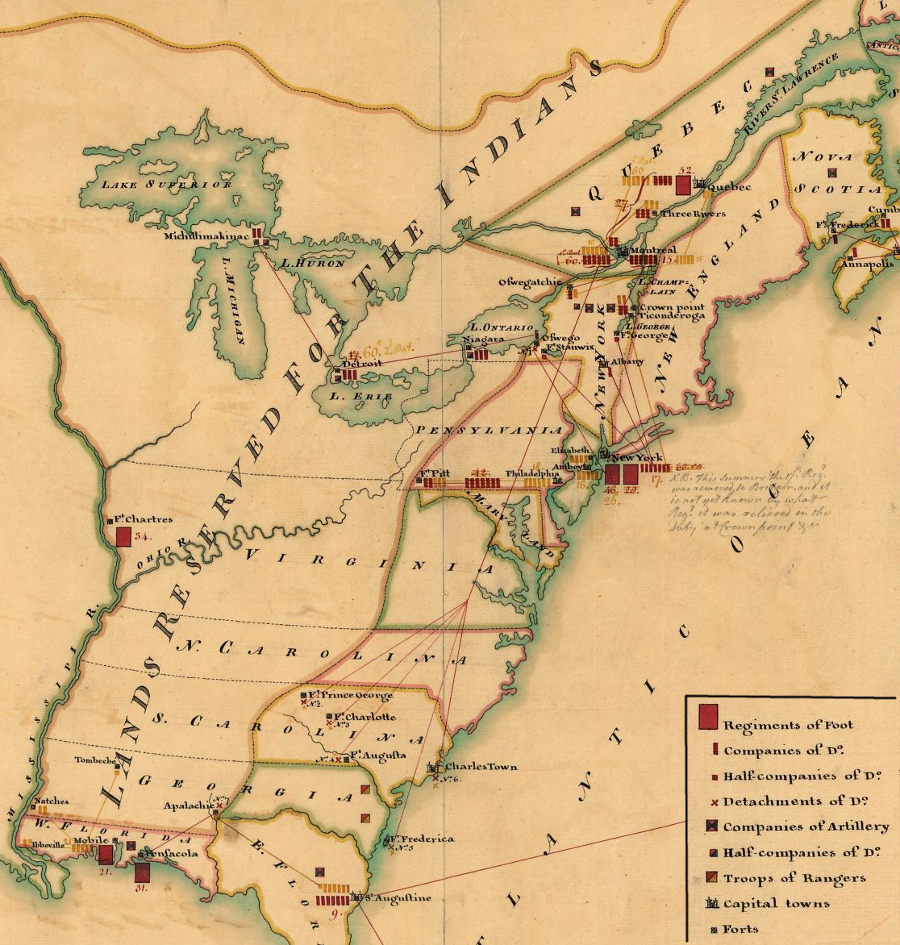

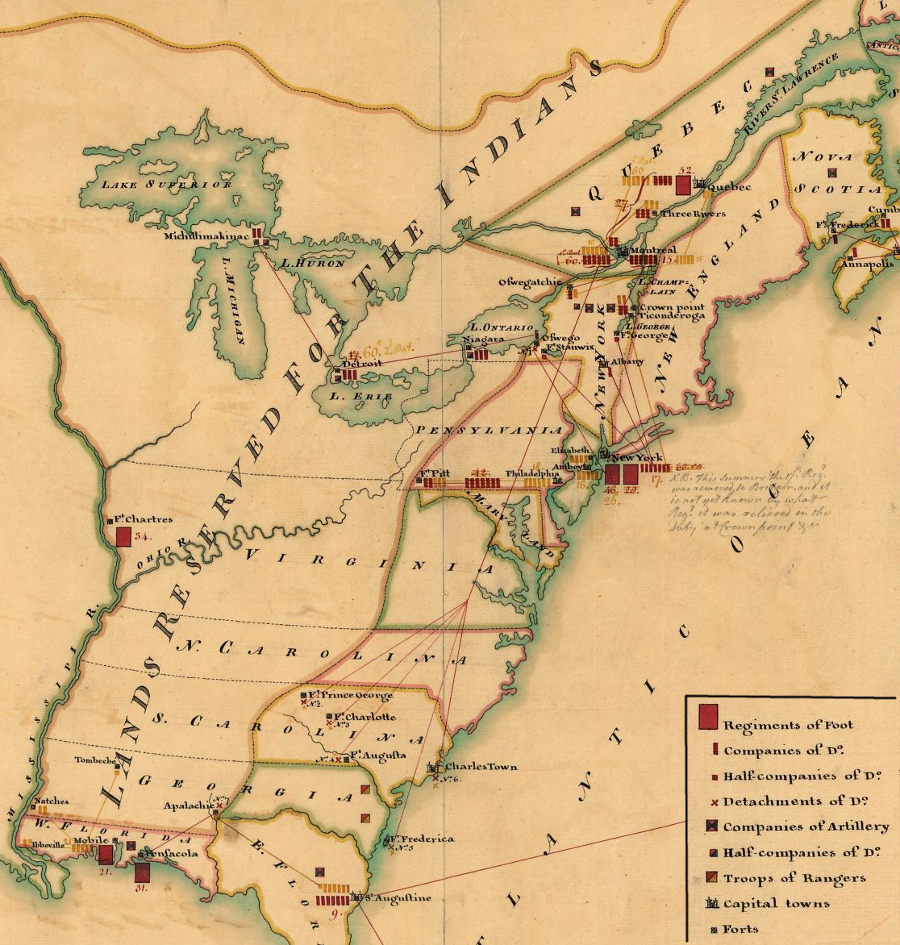

in 1766 the British military was concentrated in areas acquired from France and Spain, and there were no forts in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Cantonment of His Majesty's forces in N. America according to the disposition now made & to be compleated as soon as practicable taken from the general distribution dated at New York 29th. March 1766

The Proclamation of 1763, issued by George III on October 7, 1763, established a line that was one of many attempts to define a boundary that would separate colonists from Native Americans. The intent of the separation boundary was to reduce conflict and thus the costs to maintain peace in the border zone between two cultures.

British officials intended for the Proclamation Line of 1763 to minimize the need for new forts in the contact zone between colonists and Native Americans, and to reduce the need for expensive troops to be stationed and supplied on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Historian Woody Holton argues that in 1762, the leaders in the colonies were satisfied to be part of the British Empire. They received military protection against the French, Spanish, and Native Americans without paying a fair share of the costs.

The Americans were able to ignore Parliament's mercantilist restrictions, which were designed to limit colonist's trade to just British sites within the empire. Direct trade to France or the Netherlands, or to any other place controlled by another European country, was prohibited. American trade was supposed to enrich England with fees and taxes.

Such trade brought cheap raw materials from North America to England. Restricting trade also ensured England captured a large consumer market; American colonists could purchase manufactured goods only from England. Because the Americans were evading the trade restrictions, particularly by sending ships to Caribbean islands controlled by other nations, taxpayers in England were subsidizing the defense of the colonies.

The British Navy could keep Spain and France from landing a large army in North America, but only British troops could protect against attacks by Native Americans on the western edge of settlement. To minimize the cost of the defense subsidy, Parliament needed a different strategy to minimize the threat of Native American attack.

That strategy was to control the westward migration of colonists, whose seizure of Native American lands was the trigger for conflict. If the Proclamation Line of 1763 had been successfully enforced, then there would have been no need to raise funds by a Stamp Act tax in 1765, or other taxes which spurred revolution:1

- Britain wanted to stop land speculators, like George Washington and Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. The British government wanted to stop them from stealing land from the Indians because whenever you do that, you provoke a war with the Indians. And the British government understood something that a lot of people today forget. And that is, the most expensive thing that any government ever does is go to war.

- And so the British said, OK, again, this is not out of sympathy. This is a matter of strategy. What do we need to do to appease the Indians and keep them from attacking our colonies? And that is, have the colonies stop stealing their land.

Virginia officials in Jamestown, Williamsburg, and finally Richmond never solved the problem of how to expand settlement and maintain peace with the Native Americans. The 1763 edict from King George III was the last of multiple attempts by colonial officials in England and Virginia to establish a border separating colonists from the original occupants of the land. It was no more successful than other limit-of-settlement lines defined as far back as 1619.

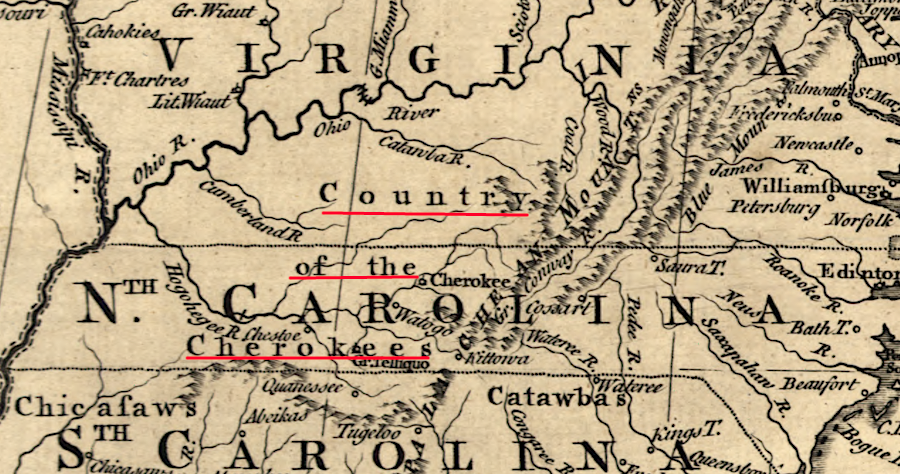

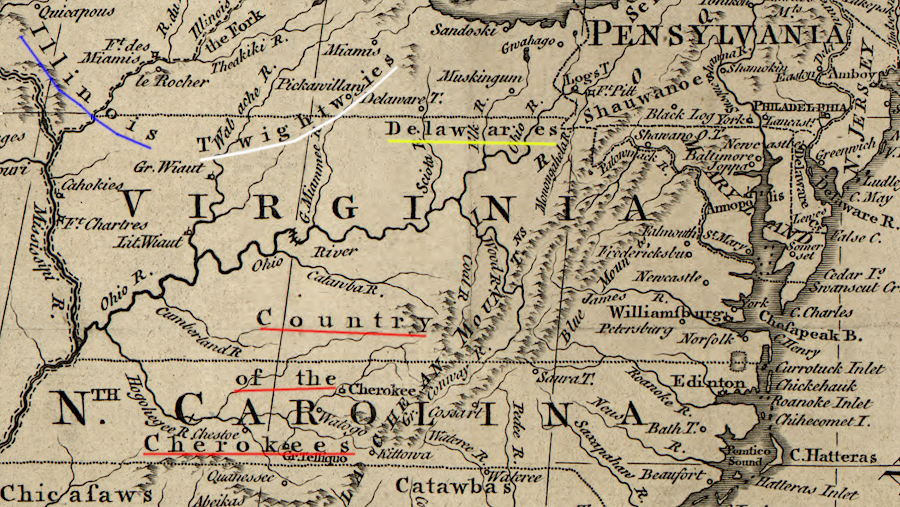

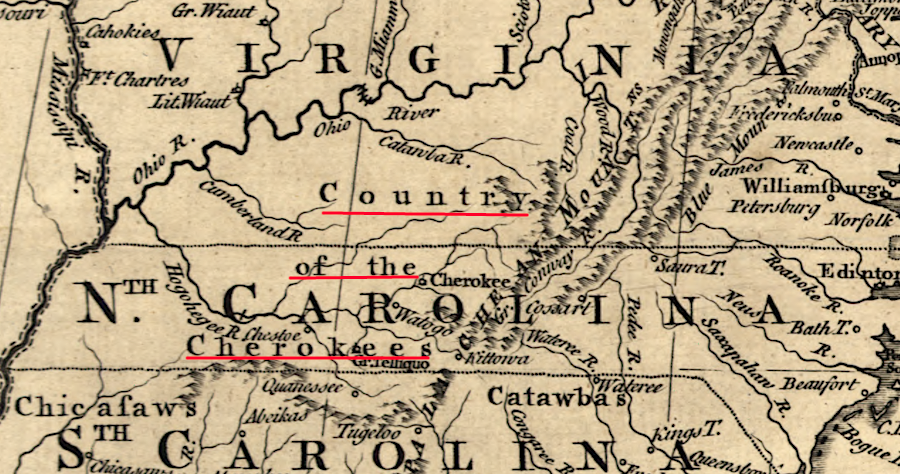

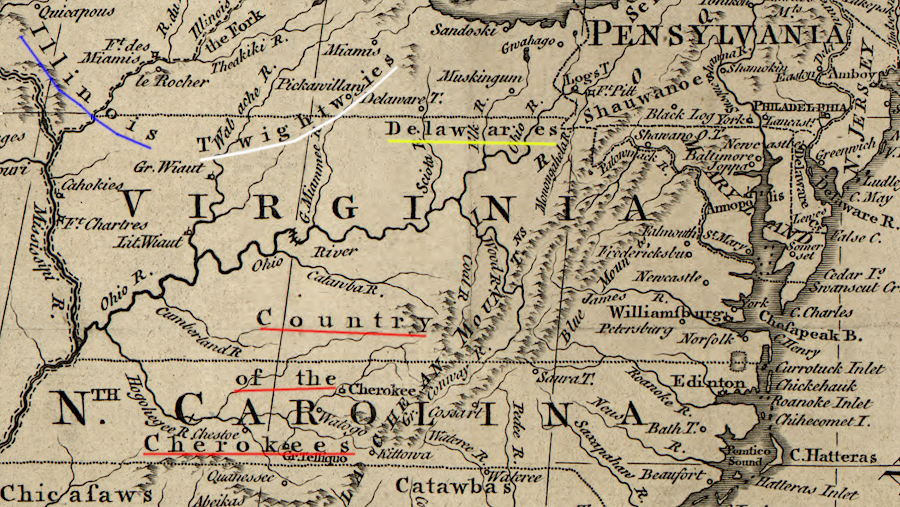

Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia claimed lands west to the Mississippi River after the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North America (by Emanuel Bowen, 1763)

After Virginia relinquished its claims to the Northwest Territory across the Ohio River to the Congress in 1781 and Kentucky became an independent state in 1792, Virginia no longer claimed lands that were still occupied by Native American tribes. Making peace with the Native Americans became a problem for Federal officials - but since seven of the first twelve presidents were born in Virginian, the state's perspective remained significant even after cession of western land claims.

Starting in 1607, John Smith and other colonial leaders sought to extend England's control over territory and to reduce the power on the Native Americans. Competition over land led to three Anglo-Powhatan wars during 1609-1646, as the English displaced the Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living on the Coastal Plain.

Starting with the first Jamestown Fort in 1607, followed in 1611 with construction of a palisade to fortify the site of Henricus, the colonists sought to isolate "English" territory from "Native American" territory. In 1613 Bermuda Hundred was blocked off by a wooden wall, distinguishing colonists-only territory and excluding Native Americans.

To minimize the potential for individuals in the colony to irritate the Native Americans and trigger retaliation, the first meeting in 1619 of what became the House of Burgesses required colonists to stay within a limited territory. The legislature passed laws that mandated:2

- That no man may go above twenty miles from his dwelling place, nor upon any voyage whatsoever shall be absent from thence for the space of seven days together, without first having made the Governor or commander of the same place acquainted therewith, upon pain of paying twenty shillings to the public uses of the same incorporation where the party delinquent dwells.

- That no man shall purposely go to any Indian towns, habitation, or places of resort without leave from the Governor or commander of that place where he lives, upon pain of paying 40 shillings to public uses as aforesaid.

immediately after the French and Indian War, English magazines highlighted both the expansion of colonial territory (tinted brown) and the existing inhabitants

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of North America, shewing the advantages obtain'd therein to England by the peace (May, 1763)

After the 1622 uprising, the General Assembly considered building a wooden barricade between Martins Hundred and Kiskiak/Chiskiack (now the Naval Weapons Station at Yorktown). Colonists reinforced their individual houses, rather than build the wall. In 1633 at the conclusion of the Second Anglo-Powhatan War, a palisade was constructed further upstream between College Creek (called Archer's Hope at the time) and Queens Creek. That forced the Kiskiak/Chiskiack tribe to migrate north across the York River.3

location of proposed 1622 palisade (blue) and 1633 palisade (red),

excluding Algonquians from Peninsula

Source Map: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) MyWaters

The first Native American "preserve" to be established in Virginia was Indiantown Neck on the Eastern Shore. 1,500 acres were designated for use by the Accomac (Gingaskin) tribe in 1640, establishing a model used to create reserved lands (reservations) for other tribes.

The 1644 uprising led to the Third Anglo-Powhatan War and the end of the paramount chiefdom in eastern Virginia once led by Powhatan. The victorious colonists forced the putative "emperor," Necotowance, to sign a 1646 peace treaty that restricted Native Americans to lands west of the Blackwater River and north of the York River.

Theoretically English settlement was prohibited north of the York River, except for the land south of Poropotank Creek (current boundary of Gloucester-King and Queen counties). All trade was to be channeled through specific forts, and Native Americans were required to wear "a coat of striped stuff" when inside the restricted zone.4

Despite the promises, English settlement was quickly authorized in the territory north of the York River that was supposedly reserved for the Native Americans. Rather than live in compact towns, the colonists established scattered tobacco plantations and isolated "quarters" that intruded into traditional hunting territories.

As colonial settlement expanded, the English sought to minimize conflict by designating areas reserved for Native American occupation:5

- Just as specific tracts had been assigned to the Eastern Shore's Accomack Indians in 1640 and to the Pamunkey, Kiskiak/Chiskiack, and Weyanoke in 1649, during the early 1650s acreage was assigned to the Rappahannock, Totusky, Moratticund, Mattaponi, Portobago, Chickahominy, Nanzattico, Nansemond, and upper Nansemond (Mangomixon), and perhaps others as well. Many of these Native preserves lay in the Middle Peninsula or Northern Neck.

In 1658, the General Assembly declared that settlers could not acquire land from Native Americans via private purchases. All expansions of settlement had to be processed through the quarterly courts held at Jamestown, in order to avoid creating a reason for Native American attacks.

Creating a boundary to separate "English" from "Native American" territory did not succeed in limiting conflict. Indentured servants who completed their term of service moved to the edges of English occupation to establish new farms where rights to land were easiest to acquire, expanding the zone of settlement and intruding deeper into Native American territory.

Borderland conflicts based on the land hunger of colonists finally erupted into Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. Though the backcountry raids were led by Dogue and Susquehannock, Nathaniel Bacon's forces did not distinguish between good and bad Native Americans. Peaceful Pamunkey and Occoneechee living where they were "supposed to be" were attacked, and their furs and accumulated wealth were stolen.

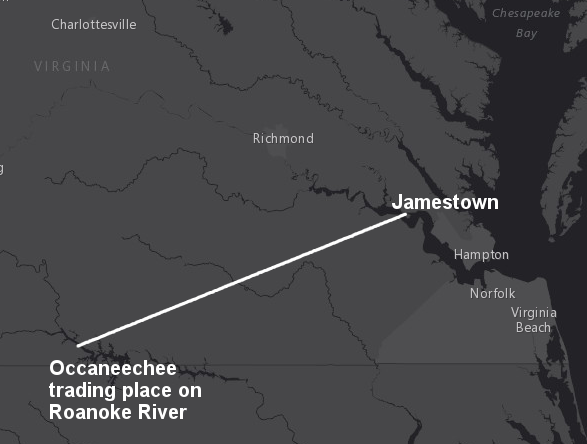

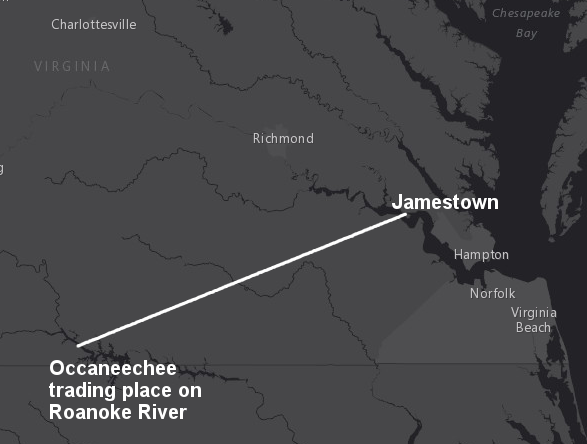

the rebels under Nathaniel Bacon attacked the Occoneechee, 100 miles from Jamestown

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Bacon's Rebellion was followed by the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1676. The English gradually abandoned the idea that towns occupied by "tributary tribes" could serve as a buffer against raids by the Iroquois or Susquehannock.6

"Outrages" in the border area were perpetrated by both sides for another century. Isolated groups of Native Americans or settlers were attacked/murdered with little or no provocation, retaliatory raids created more hostility, and the cycle of violence and vengeance continued intermittently.

Raiders on both sides justified their actions based on a philosophy of collective responsibility. If a colonist was attacked by a Native American, it was not required to identify and punish the individual perpetrator; colonists could respond by attacking any Native American. Similarly, if settlers attacked Native Americans, then it was legitimate for that tribe to balance the score by burning, capturing, and killing at whatever settler farm was convenient.

Native American groups living within Tidewater Virginia were effectively suppressed after Bacon's Rebellion, but problems continued with tribes on the borders. Throughout the 1700's, multiple treaties sought to separate the Native Americans from the English while legitimizing settlement on more territory. Each treaty expanded the area for colonial occupation and reduced the land base of different tribes.

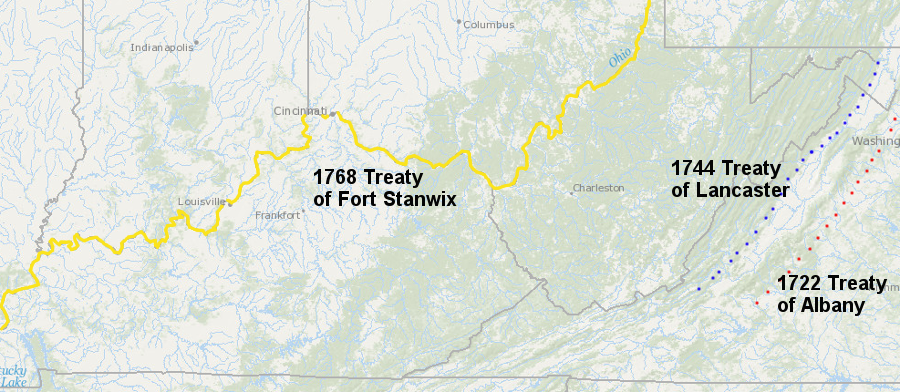

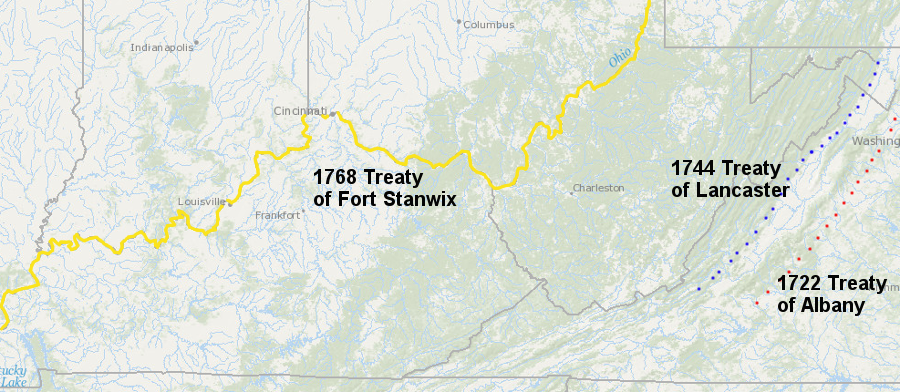

In the 1722 Treaty of Albany, Governor Spotswood negotiated with the Iroquois based in New York to push their hunting expeditions (and raids on the Cherokees) west of the headwaters of the rivers flowing into the Chesapeake Bay. In 1744 in the Treaty of Lancaster, the Iroquois agreed to stay west of the Shenandoah Valley.

Attempts by colonists to acquire western lands were complicated. Colonial charters included overlapping grants of western lands and colonial borders were not clearly defined. Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut claimed the right to sell the same land, and purchasers had to take the risk that their legal right to owning a parcel of land could evaporate. Officials in London chartered multiple land companies that claimed hundreds of thousands of acres, but without clearly defining where those land grants were to be located.

Colonies competed for the fur trade with Native American tribes. Attempts to limit the sale of weapons, gunpowder, and liquor by one colony were undercut by other colonies. There was no effective enforcement mechanism for trade regulations. Traders who cheated sellers of deerskins and furs triggered a response, but often the aggrieved Native Americans retaliated against other colonists/traders who were not directly responsible.

Native American tribes were equally inconsistent in their dealings with the colonists. Different groups were skillful in forcing the British to compete with the French in Canada for business. When the British were unwilling to sell items to the Native Americans, the French took advantage of the opportunity.

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Susquehannock, Delaware, Shawnee, Miami, and Cherokee were enticed to authorize expanded western settlement in fragmented agreements. Tribal leaders were willing to sign agreements for settlement on lands for which other tribes claimed as their hunting grounds. Other than the Haudenosaunee, Native American groups lacked central governments which could make enforceable deals. New settlers on western lands had to accept the risk that they could be attacked by one or more groups who did not feel bound by a treaty.

In 1754, representatives from seven colonies agreed to the Albany Plan of Union drafted by Benjamin Franklin. the forcing action for inter-colonial cooperation was establishing a common defense at the outbreak of the French and Indian War.

No colony actually adopted the plan drafted by Benjamin Franklin. Back in London, British officials became more assertive in managing the colonies, shifting away from the benign neglect of them used ever since 1607. A Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Colonies and a Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Colonies were appointed in 1756 to control negotiations and trade deals with Native American tribes, which previously had been managed by individual colonies and companies in competition with each other. The superintendents struggled to reconcile inconsistent promises made to different tribes, and to break alliances with the French.

During the French and Indian War, British military commanders arranged for logistical support and managed local recruits using royal authority. Colonial officials did not coordinate with each other to orchestrate united support for campaigns.

The Albany Plan of Union proposed adopting a common mechanism for managing the Indian trade, acquiring/settling western lands, and coordinating the construction of forts to create an effective line of defense on the westernboundaries of the various colonies. Land acquisition would be centralized and new colonies in the west would be established, with a planned pattern of forts to defend settlements as they expanded westward.

The 1754 plan proposed that the cost of defense would be reduced by synchronizing Native American trade, land purchases, and fort construction. The assumption was that colonial expansion could be facilitated by slow growth westward. Native Americans who objected to rapid and scattered colonial expansion wwere expected to accept gradual cessions of their land, with compensation:7

- It is much cheaper to purchase of them, than to take and maintain the possession by force: for they are generally very reasonable in their demands for land; and the expence of guarding a large frontier against their incursions is vastly great; because all must be guarded and always guarded, as we know not where or when to expect them...

- It is supposed better that there should be one purchaser than many; and that the crown should be that purchaser, or the union in the name of the crown. By this means the bargains may be more easily made, the price not inhanced by numerous bidders, future disputes about private Indian purchases, and monopolies of vast tracts to particular persons (which are prejudicial to the settlement and peopling of a country) prevented; and the land being again granted in small tracts to the settlers, the quit-rents reserved may in time become a fund for support of government, for defence of the country, ease of taxes, &c.

- Strong forts on the lakes, the Ohio, &c. may at the same time they secure our present frontiers, serve to defend new colonies settled under their protection; and such colonies would also mutually defend and support such forts, and better secure the friendship of the far Indians.

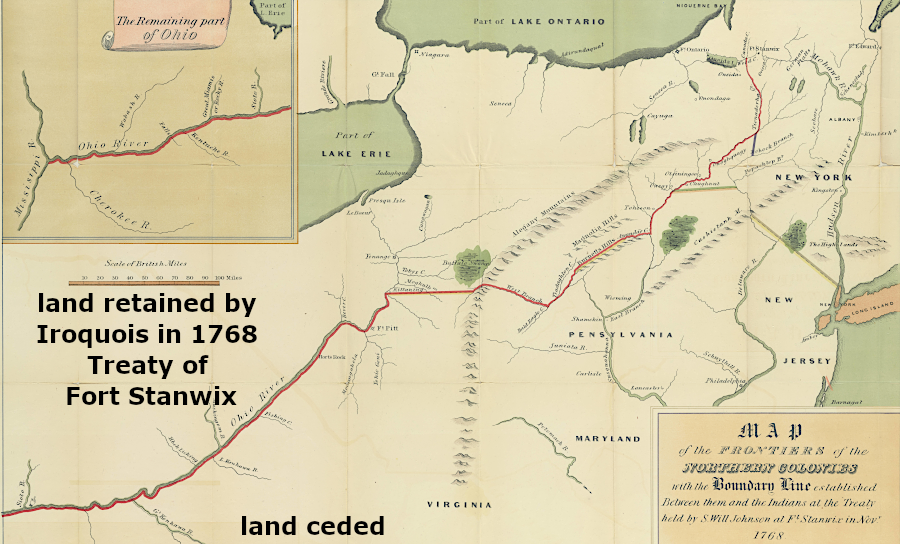

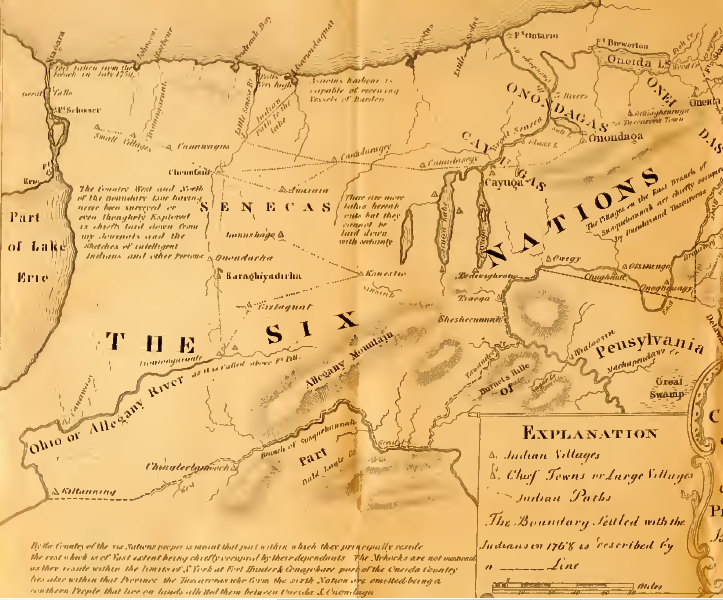

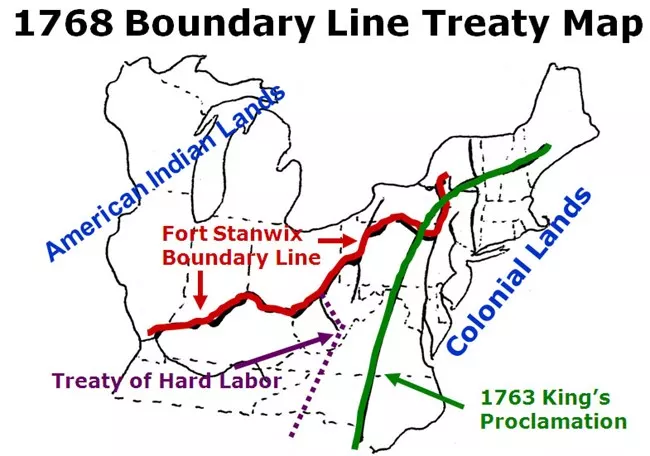

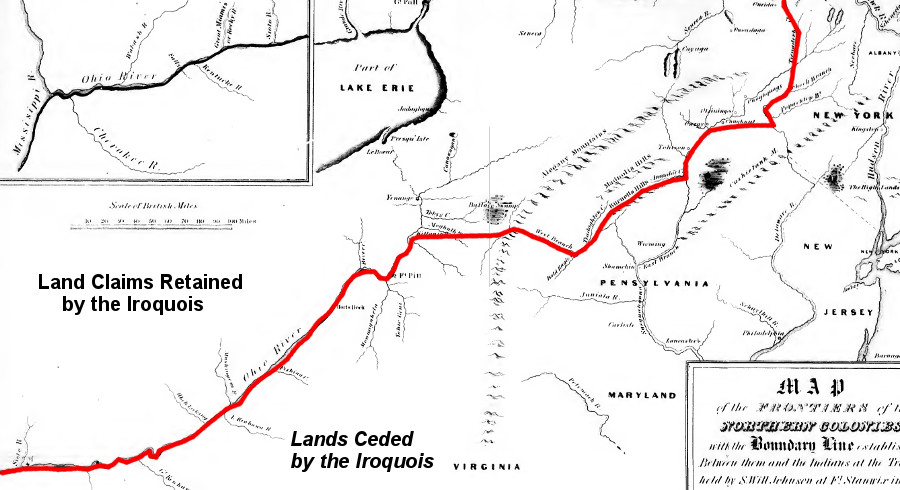

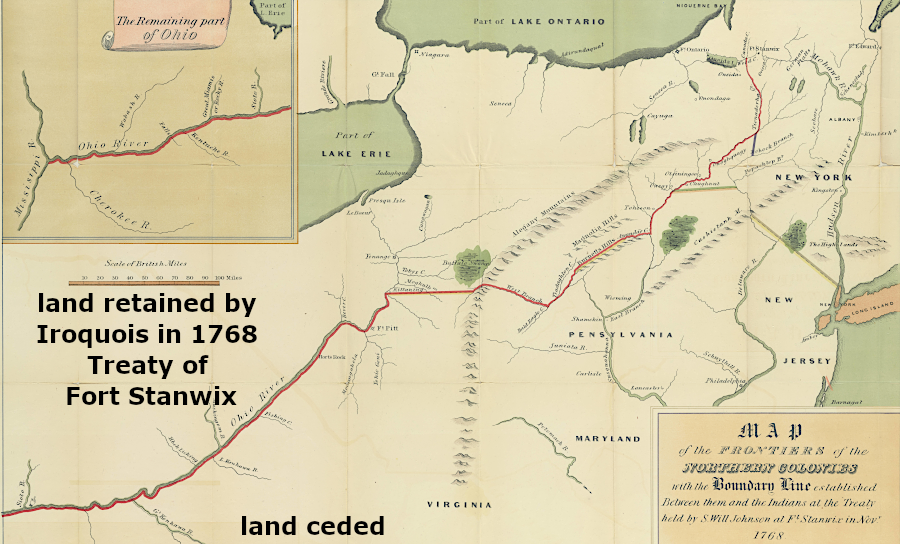

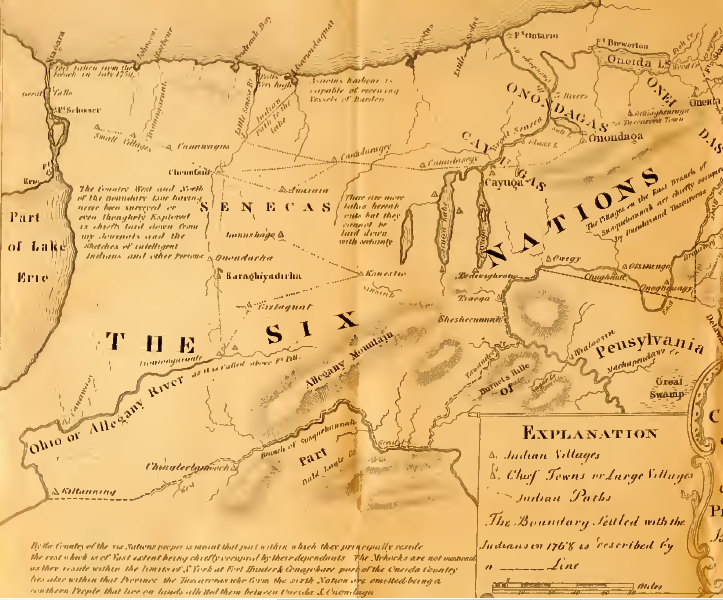

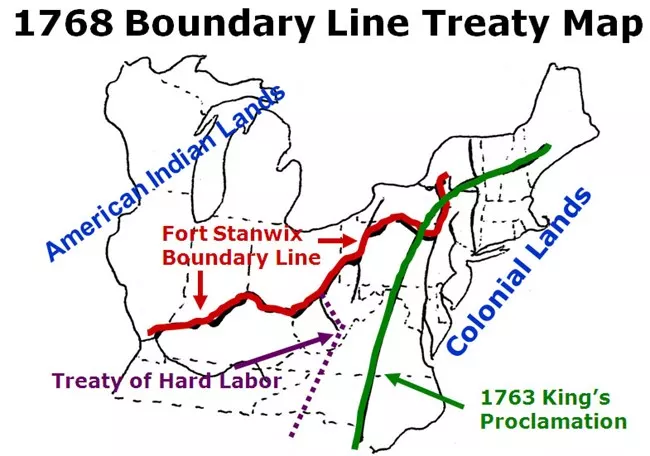

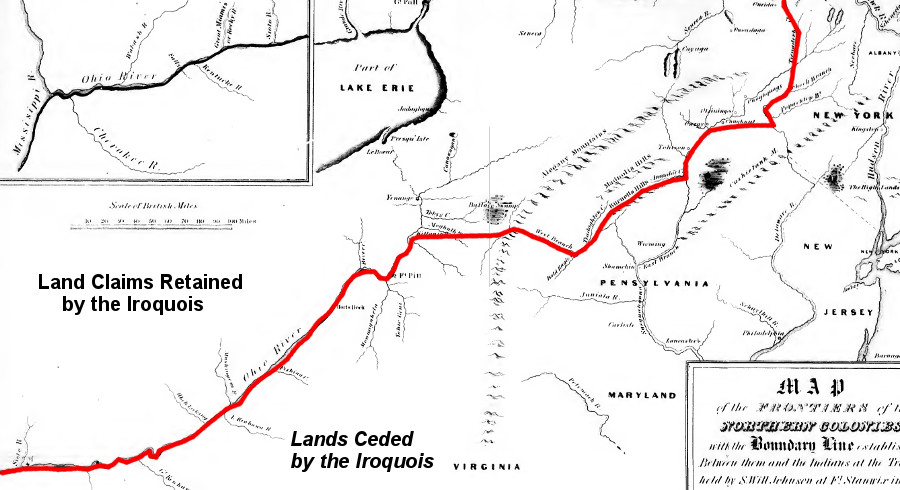

In 1768 in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) abandoned their claims to lands south of the Ohio River.

the Iroquois relinquished their claims to lands south of the Ohio River in the 1722 Treaty of Albany, the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster, and the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Iroquois cession of land claims in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix extended to the Mississippi River

Source: Penn State, Map of the frontiers of the northern colonies : with the boundary line established between them and the Indians at the treaty held by S. Will Johnson at Ft. Stanwix in Novr. 1768

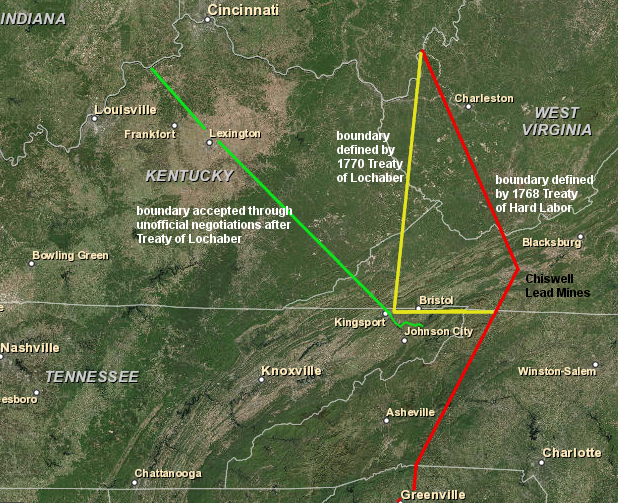

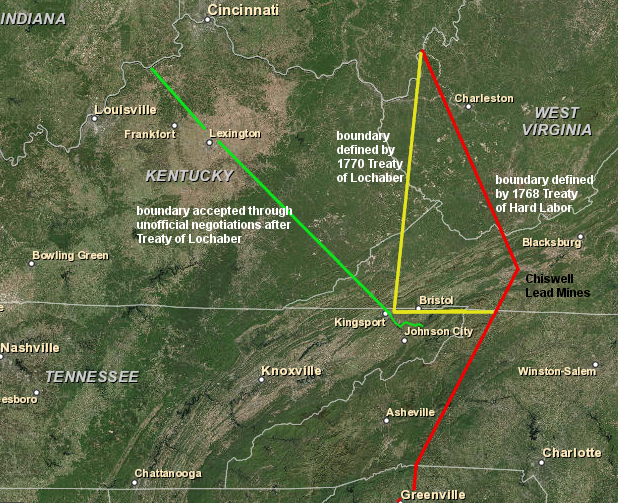

In the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor and the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, plus informal side agreements, the Cherokee ceded their claims to Virginia as far west as the mouth of the Kentucky River.

As settlers sought cheap farmland, colonial settlement extended west of the Appalachian Mountains. English and colonial officials recognized that the European population in North America (and the population of slaves imported originally from Africa) would grow substantially. Native Americans on the western boundaries of the colonies would have to be expelled, and their land claims would have to be extinguished or finessed.

Massive land grants to the Ohio Company in 1748 and the Loyal Land Company in 1749 reflected the understanding that a critical mass of farmers would begin to produce crops beyond the Eastern Continental Divide. Once the lands in the watersheds of the Ohio, Kanawha, Greenbrier, and Tennessee rivers were settled, agricultural trade would go down the Mississippi River rather than directly to the Atlantic coastline.

The expected shift of population to the west had substantial political ramifications. The French claimed the Ohio River watershed, and Spain controlled New Orleans and the Mississippi River trade.

the French published maps claiming the English had no authority west of the Allegheny Front

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Louisiane et du cours du Mississippi ... (by Guillaume de L'Isle, 1718)

In 1763, the English victory in the French and Indian War (known in Europe as the Seven Years War) eliminated the power of the French to supply Native Americans who resisted Virginia's colonial expansion into the watersheds of the Ohio River and other drainages that flowed west to the Mississippi River.

In the treaty negotiations, France chose to retain its sugar-producing, profitable Caribbean islands that had been captured by the English. Canada, which had required subsidies rather than produced a profit, was ceded to the victorious English who had possession of the land. France retained only the islands or Miquelon and St. Pierre at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, plus fishing rights near Newfoundland.

The English agreed to allow the French Catholics to continue to practice their religion in Canada, and French culture has survived to this day in Quebec. The English did not try to suppress it as they had done in Nova Scotia in the 1750's. After 1763 the military threat from any French-occupied land had been eliminated. Toleration created less threat of a future uprising or support for a French invasion in North America.

The 1763 treaty also reshaped Spanish claims in North America. After Spain joined France in the war, the British captured Havana. In the peace treaty, Spain reclaimed Cuba by granting East and West Florida to the British.

To make Spain whole after the cession of Florida, France gave to Spain in the Treaty of San Ildefonso all claims to the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River. New France disappeared from the map of North America after the 1763 Treaty of Paris.8

at the end of the French and Indian War, French negotiators at the Treaty of Paris traded away Canada and the Ohio Valley in order to retain sugar-producing islands in the Caribbean, and Virginia gentry with land grants expected to profit by selling western lands to new settlers

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North America. Describing and distinguishing the British, Spanish and French dominions on this great continent; according to the definitive treaty concluded at Paris 10th Feby. 1763 (Emanuel Bowen, 1767)

The Virginia gentry with existing land grants, and other colonial leaders who saw the potential for getting a government-granted windfall, expected easier access to the unsettled lands claimed by Virginia. They based the right of the Virginia colony to grant western lands on the Second Charter of 1609.

Unfortunately for the land-hungry gentry, defeat of the French did not bring peace to the western edge of colonial settlement. Before war was declared between Great Britain and France in 1755, the European rivals had fought in North America through proxies. The rival European powers had recruited different Native American tribes (or the same tribes at different times) to attack traders associated with the other side.

after the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the French retained two islands near Newfoundland but no lands on the North American continent, thus eliminating the opportunity for Native American tribes to use potential French alliances when negotiating with the British

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Possessions of European States in East North America after the Treaty of Paris, 1763 (Plate 41a, digitized by University of Richmond)

After the French were expelled in 1763, the Native Americans were not immediately willing to accept British hegemony. They recognized that without two European nations competing for the support of the tribes, they lacked the capacity to obtain weapons need to block English settlers from moving westward. That awareness increased the willingness of different tribes to cooperate.

Allied groups from different Native American nations launched desperate attacks on the western settlements from New York to Virginia. The Shawnee and Delaware in particular recognized that the British would grow stronger over time, and without access to French gunpowder and weapons the Native Americans would grow weaker.

Pontiac's Rebellion, starting with the siege of Fort Detroit in April 1763, caught the British unprepared. Native American tribes north of the Ohio River united together under the leadership of the Odawa chief Obwandiya (called "Pontiac" by the British) and captured nine western British forts ranging from Fort Edward Augustus to Presqu'Isle. Only the forts at Detroit, Niagara and Fort Pitt managed to withstand sieges.

It was clear to the political, business, and military leaders in London that the expensive Seven Years War/French and Indian War to defeat the French could be followed by expensive peacekeeping operations on the edges of the colonies. Regiments raised for the war could not be demobilized or withdrawn completely; soldiers kept in North America would have to be supplied and paid. Taxes in England would have to stay high in order to subsidize the military occupation of lands newly acquired from France. Paying interest on the debt accumulated to pay for the Seven Years War would continue to strain the British budget.

Colonists on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean would be the primary beneficiaries of the continuing military presence. Colonists expected to continue to pay the indirect taxes such as import and export duties (tariffs), but did not anticipated being burdened by new taxes to pay for the recent war or continued defense. From the colonial perspective there were no elected representatives with the authority to impose new forms of taxes, since there were no colonists sitting in Parliament.

The gentry in Virginia and leaders in other colonies anticipated that defeat of the French and their Native American allies would make western lands available immediately for unrestricted settlement. The French claim to the land had been extinguished. The Native Americans had lost the one European ally providing guns and supplies, so they could be displaced involuntarily. A wave of settlers could move west to create new farms on parcels that would be sold by the speculators who had invested in land companies.

In London, the Board of Trade and the Secretary of State for Southern Affairs had a different view of how to creating rewards from victory in North America, and how to repay the money that had ben borrowed to finance the costs of the Seven Years War.

British officials knew their new empire required funds for military protection, but Great Britain could not afford to perpetuate an unending series of wars with Native Americans in North America. The solution was to raise more funds in North America and to reduce costs there:9

- The foremost task facing Britain was meeting the costs of victory. To gain and maintain the new empire cost great sums of money which the crown knew it could not extract from British taxpayers already overburdened with levies on land, imports, exports, windows, carriages, deeds, newspapers, advertisements, cards and dice, and a hundred other items of daily use.

- The land tax, for instance, was 20 percent of land value. These were taxes parliament had levied on residents in Great Britain but not on the colonists. Many taxes had been in effect since an earlier war in the 1740's (King George's War). With the national debt at a staggering £146,000,000, much of it the result of defending interests in the New World, and several million pounds owed to American colonies as reimbursement for maintaining troops during the war, British taxpayers, rich and poor alike, expected relief.

- In fact, these war debts forced parliament to impose additional taxes in 1763, including a much-despised excise tax on cider. It is hardly surprising to find most Britons agreed that in the future the Americans should be responsible for those expenses directly attributable to maintaining the empire in America. That future costs were to be shared seemed politically expedient and the reasonable thing to do. Every ministry which came to power in Britain after 1763 understood this as a national mandate it could not ignore.

To reduce the costs of managing the borderlands, colonial land hunger would have to be curbed.

British officials also wanted to limit westward expansion and force population increases in Canada and Florida. That pattern of population growth would increase trade across the Atlantic Ocean to the British Isles, while westward settlement would create agricultural surpluses that would be exported via the port at New Orleans which the Spanish controlled. The mercantilist philosophy of the time called for the colonies to maximize wealth in the mother country, not to generate business for Spain.10

the Proclamation of 1763, the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and later the Townshend duties inflamed colonial opposition to rule from London and stimulated the American Revolution

Source: John Carter Brown Library, The Bostonian's Paying the Excise-Man, Or Tarring & Feathering

The Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Southern Department was instructed to meet with the tribes in his region and reassure them that the British sought peace after the French left, and to prevent the tribes from joining in an alliance with northern tribes that would expand the threat of Pontiac's War. John Stuart organized an assembly in Augusta, Georgia for Cherokee, Catawba, Creek, Chickasaw and Choctaw leaders to meet with the governors of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Francis Fauquier sailed from Williamsburg to Charles Town and then to Augusta, where he and the other governors negotiated with the tribal leaders between November 5-10, 1763.

in 1763, the British accepted the Cherokee claim to lands up to the Ohio River

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the British Dominions in North America; with the limits of the governments annexed thereto by the late Treaty of Peace, and settled by Proclamation, October 7th 1763

Arrangements for that meeting in Augusta had started after the beginning of Pontiac's War, and before George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War had been signed on February 10, 1763. Pontiac's War erupted in April, and the proclamation was issued on October 7, 1763. The governors had not received official copies of the proclamation when they went to Augusta. In the Treaty of August, the Cherokee agreed to a line defining the eastern boundary of their territory and the Catawba agreed to accept a 15-square mile reservation.

there were no British forts west of the Blue Ridge in North and South Carolina when the Treaty of Augusta was signed in 1763

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the British Dominions in North America; with the limits of the governments annexed thereto by the late Treaty of Peace, and settled by Proclamation, October 7th 1763

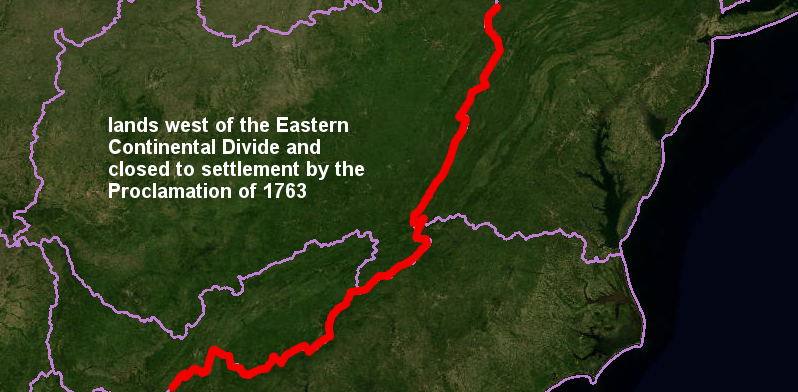

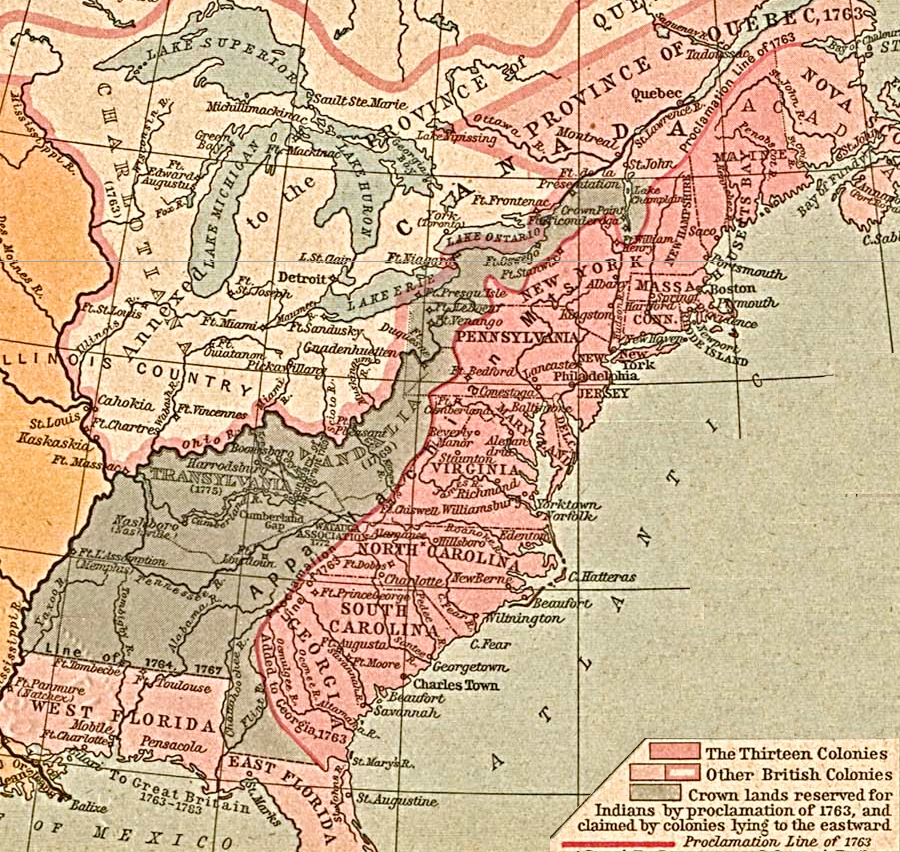

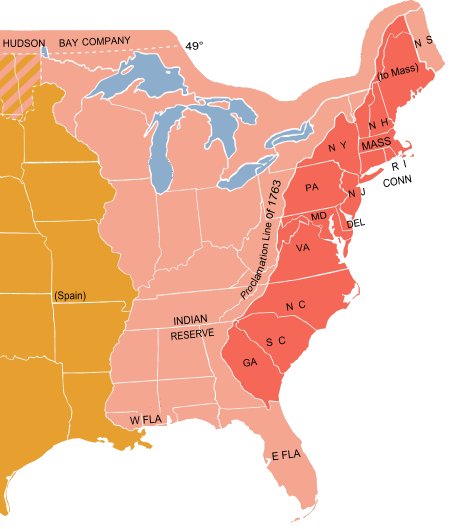

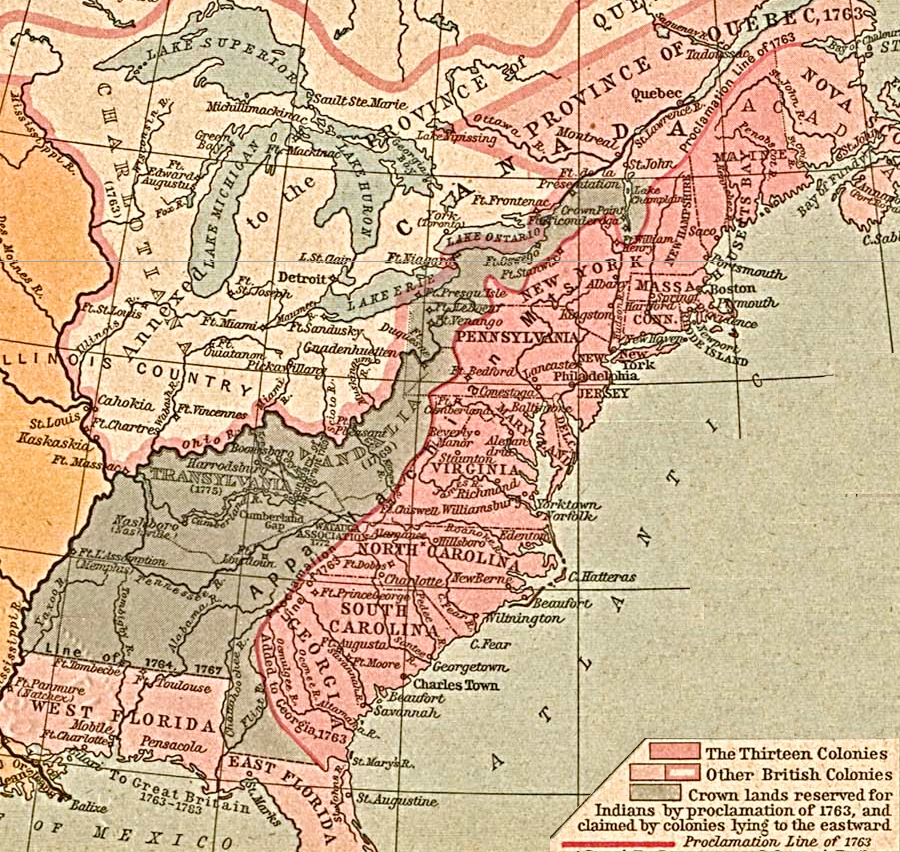

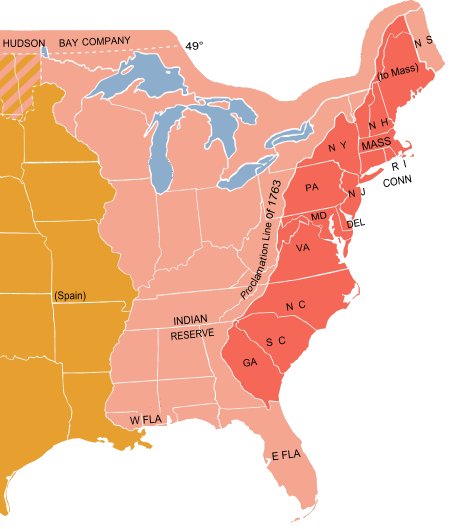

The Proclamation of 1763 created new provinces (Quebec, West Florida, East Florida and Grenada) out of lands acquired from the French, plus a huge "Indian Reserve" closed to settlement. The Indian Reserve included all the acquired land in North America outside the boundaries of Quebec, West Florida, and East Florida. The Indian Reserve included all land west of the Appalachians.

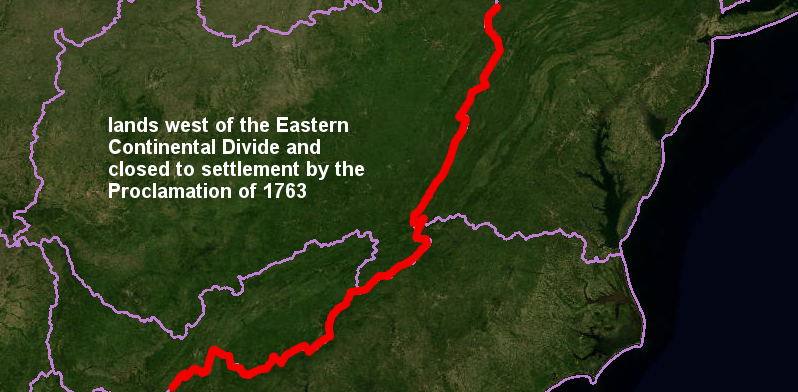

Much to the dismay of the colonists, the proclamation blocked the ability of various land companies to make profits by claiming ownership, based on existing or prospective grants from royal officials, and selling parcels to settlers. George III prohibited colonial governors from authorizing surveys or issuing land grants beyond the Proclamation Line drawn at the crest of the Alleghenies. Overnight, Virginians were blocked from moving to the territory west of the Eastern Continental Divide separating the watersheds of rivers flowing to the Atlantic Ocean from rivers flowing to the Gulf of Mexico.

the Proclamation of 1763 defined a boundary blocking settlement (red line), based on the Eastern Continental Divide

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Hydrography Viewer

All English settlers living on the western side of the Eastern Continental Divide - including those already living in the valleys of the New River and the Holston River - were supposed to leave "forthwith." The British objective was to minimize conflicts with the tribes, and thus reduce the costs to the English government of defending the colonies from Native American raids. After the start of the French and Indian War and the failure of the colonies to adopt a united approach to Native American trade and western settlement at Albany in 1754, London officials exerted more direct control over colonial affairs.

The Proclamation of 1763 was clear [emphasis added]:11

- And We do further declare it to be Our Royal Will and Pleasure, for the present as aforesaid, to reserve under our Sovereignty, Protection, and Dominion, for the use of the said Indians, all the Lands and Territories not included within the Limits of Our said Three new Governments, or within the Limits of the Territory granted to the Hudson's Bay Company, as also all the Lands and Territories lying to the Westward of the Sources of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the West and North West as aforesaid.

- And We do hereby strictly forbid, on Pain of our Displeasure, all our loving Subjects from making any Purchases or Settlements whatever, or taking Possession of any of the Lands above reserved, without our especial leave and Licence for that Purpose first obtained.

- And We do further strictly enjoin and require all Persons whatever who have either wilfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any Lands within the Countries above described or upon any other Lands which, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are still reserved to the said Indians as aforesaid, forthwith to remove themselves from such Settlements.

settlers already living in the New River Valley were supposed to move east of the Blue Ridge (red line), according to the Proclamation of 1763

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

The proclamation was a statement directly from the British monarch, King George III; Parliament did not pass any law in 1763 limiting settlement of western lands. The king issued the order using his royal authority to address the immediate problem of uncontrolled westward settlement that was made possible by victory in the French and Indian War. The proclamation gave the new Secretary of State for the Southern Department (Lord Halifax) and Parliament time to consider how to manage the new territory:12

- As opposed to a statute passed by Parliament - a body representative of the people - the proclamation was the embodiment of the monarch, symbolized by the fact that when the ruler died, the proclamation often did, as well. The monarch used proclamations to legislate extraordinary and often temporary emergencies that were not clearly defined by statutes.

The land hungry gentry in Virginia controlled the colony's government. Through the Ohio Company, the Loyal Land Company, and other grants the speculating Virginia gentry had acquired claims to hundreds of thousands of acres "lying to the Westward of the Sources of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the West and North West."

The Proclamation of 1763 authorized governors of Quebec, East Florida, and West Florida to grant lands to soldiers and sailors who had fought in the recent war, but only within the boundaries of the new colonies. Virginian veterans who had fought in the French and Indian War wanted to settle on lands in the Ohio River watershed which had been acquired through military action. Land-hungry Virginians, including colonial gentry who had invested in various land companies, objected to a boundary line that rewarded the Native Americans - especially tribes that had been allies of the French.

With the stroke of a pen, George III dramatically undercut the economic dreams of French and Indian War veterans and most of the political leaders in Virginia. The constraint on western settlement told them the equivalent of "drop dead." The Proclamation of 1763 made clear that the Board of Trade in London was asserting more control over colonial affairs than in the days prior to the French and Indian War. The desires of the colonial gentry, land speculators in London and North America, and French and Indian War veterans were secondary to the concerns of the financial managers in the king's government.

The Privy Council anticipated private purchases on land from Native American tribes would be one way for colonial governors and creative land-hungry members of the gentry to bypass the prohibition on settling in the Indian Reserve. The proclamation clearly blocked making deals with tribes that would transfer land ownership:13

- And whereas great Frauds and Abuses have been committed in purchasing Lands of the Indians, to the great Prejudice of our Interests. and to the great Dissatisfaction of the said Indians: In order, therefore, to prevent such Irregularities for the future, and to the end that the Indians may be convinced of our Justice and determined Resolution to remove all reasonable Cause of Discontent, We do. with the Advice of our Privy Council strictly enjoin and require. that no private Person do presume to make any purchase from the said Indians of any Lands reserved to the said Indians, within those parts of our Colonies where, We have thought proper to allow Settlement: but that. if at any Time any of the Said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said Lands, the same shall be Purchased only for Us, in our Name, at some public Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians...

The Proclamation of 1763 abruptly froze colonial westward settlement from moving into "all the Lands and Territories lying to the Westward of the Sources of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the West," the long-coveted Ohio River valley. Governor Dinwiddie had sent George Washington to Fort LeBoeuf in 1753 to demand the French leave the region, but now that territory was reserved for Native Americans.

A historical pamphlet produced by the Virginia Department of Education said succinctly:14

- The Proclamation of 1763 would separate the Indians and whites while preventing costly frontier wars. Once contained east of the mountains, the colonials would redirect their natural expansionist tendencies southward into the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida, and northward into Nova Scotia. Strong English colonies in former Spanish and French territories would be powerful deterrents to future colonial wars.

George III's Proclamation Line is consistent with modern "smart growth" land use principles where development is concentrated within urban growth boundaries, with long-range plans and zoning used to steer development to specified areas and reduce the cost of government services. Colonial land speculators, similar to modern land speculators on the "wrong" side of a growth boundary, refused to accept the 1763 political decision as final.

the Proclamation of 1763 was intended to block new colonial settlement in western New York and Pennsylvania, as well as western Virginia, North Carolina, and even Georgia

Source: Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, The British Colonies in North America, 1763-1775 (from William R. Shepherd's "Historical Atlas," 1923)

The proclamation was just a temporary freeze, like many previous efforts of the Virginia General Assembly since the 1650's to constrain the expansion of settlement in order to maintain peace with Native American tribes. The 1763 document included a key phrase: "for the present." Land companies continued to seek title to vast stretches of western lands at little or no cost from the colonial government so investors hold that land for a generation or even two, then sell off parcels as the American population expanded westward.

Virginia's newly-acquired territory west of the Allegheny Front was not "empty and ripe for settlement" in 1763

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the British Dominions in North America; with the limits of the governments annexed thereto by the late Treaty of Peace, and settled by Proclamation, October 7th 1763 (by Thomas Kitchin, 1763)

Virginia's leaders agitated constantly to open up the western lands for speculation, sale, and settlement. The concept of "conflict of interest" was very different from today, and government officials placed a high priority on increasing their personal wealth through continued land speculation. Since the Proclamation blocked conversion of land claims into cash, the 1763 boundary had to be revised.

the Indian Reserve was a barrier to western expansion by Virginia colonists

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A map of the Southern Indian district of North America (by John Stuart, 1775)

Virginia's officials expected to modify the king's limits on settlement. George Washington wrote the equivalent of "this too shall pass" to a surveyor in 1767:15

- I can never look upon the Proclamation in any other light (but this I say between ourselves) than as a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians. It must fall, of course, in a few years, especially when those Indians consent to our occupying those lands. Any person who neglects hunting out good lands, and in some measure marking and distinguishing them for his own, in order to keep others from settling them will never regain it. If you will be at the trouble of seeking out the lands, I will take upon me the part of securing them, as soon as there is a possibility of doing it...

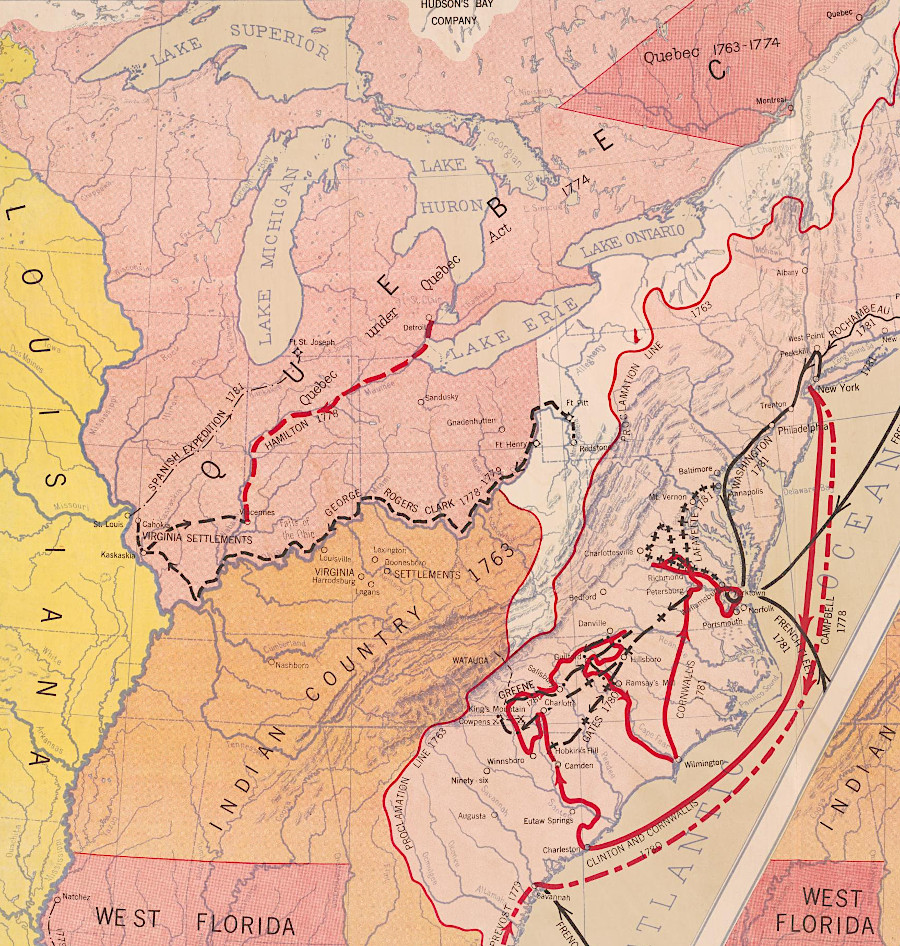

Once Pontiac signed a peace treaty at Fort Ontario in July, 1766, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District (William Johnson) and the Southern District (John Stuart) had the opportunity to negotiate adjustments to the boundary defined in the Proclamation of 1763. The Board of Trade still sought to constrain westward movement of the colonists in order to prevent new wars, but agreed to shrink the Indian Reserve in order satisfy some of the demand for land speculation and to accommodate some risk-taking families already living west of the watershed divide. Up to the American Revolution, Governor Dunmore in Williamsburg and other colonial officials appointed by London regularly facilitated the peaceful surrender of Native American land claims within the Indian Reserve.

Extension of the line of colonial settlement into "Indian Country" required support primarily from the Iroquois and the Cherokee. Though William Johnson preferred to keep them fighting each other, in 1768 he finally hosted a meeting at his home in New York where the two tribes agreed to peace. The Cherokee traveled there via ship from Charleston, to avoid the dangers of walking through Iroquois-controlled lands.

About 3,000 Native Americans attended the meeting at Fort Stanwix. They started arriving in August, and the treaty negotiations were concluded in November. Dr. Thomas Walker represented the colony of Virginia.

Johnson and Stuart negotiated two treaties in 1768 with Iroquois and Cherokee tribes to authorize settlement further west. Those treaties did not gave the English "clear title" to the lands, but Virginia officials resumed issuing land warrants, approving surveys, and confirming ownership through land patents without waiting for the elimination of any claims by the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, Ottawa, or Wyandot.

In the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois claimed to represent the Ottawas, Chippiwas, Hurons, Potowatamas, Messasagas, Miamis, Delawares, Cherokees, Chicasas, Coctas, and Creeks. They ceded claims to lands south of the Ohio River as far west as the mouth of the Tennessee River, going beyond the instructions of the Board of Trade to acquire the lands down to the mouth of the Kanawha River.

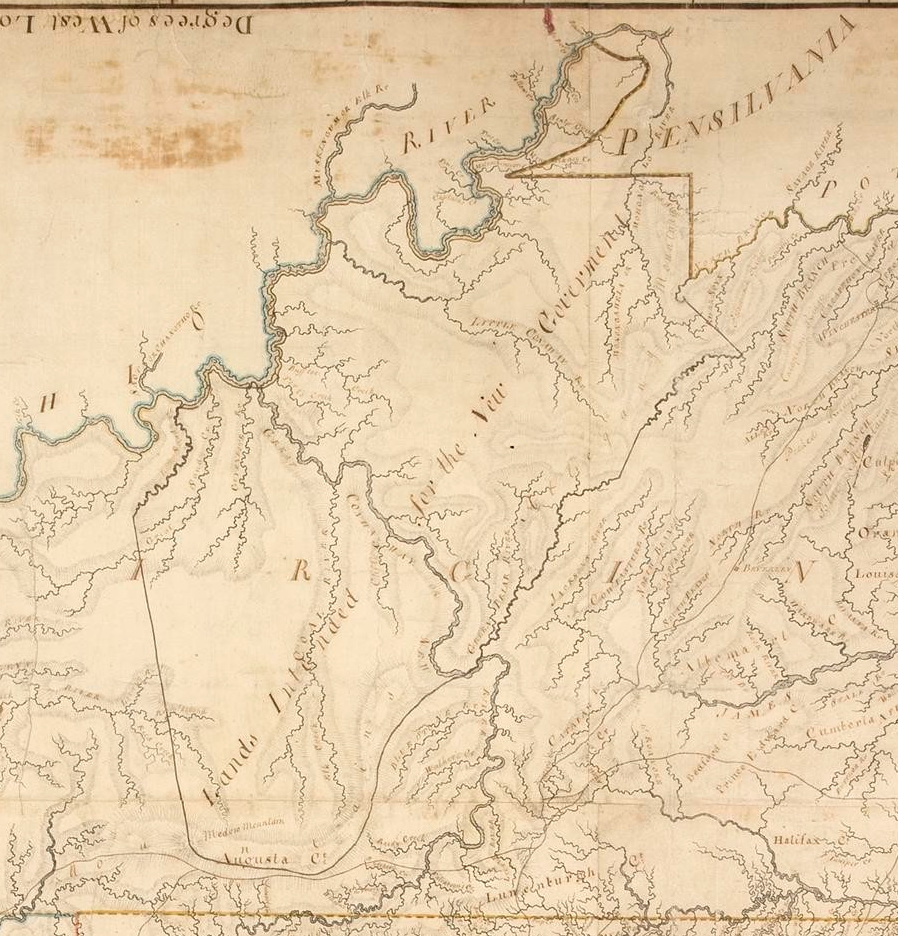

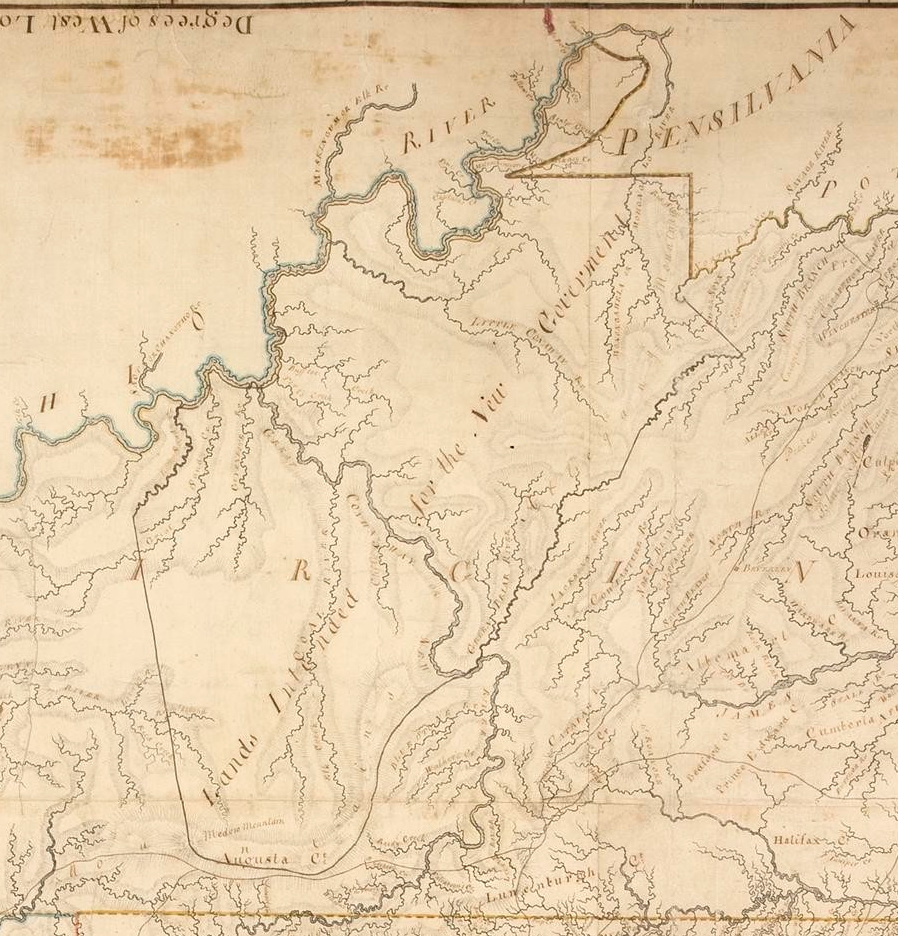

the 1771 map produced by Guy Johnson (William Johnson's son-in-law) after the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix reveals the ignorance of the British regarding lands controlled by the Iroquois

Source: E. B. O'Callaghan, The Documentary History of the State of New-York (p.1090)

In the separate Treaty of Hard Labor in 1768 and then the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, the Cherokee ceded their claims to lands south of the Ohio River and west of the Blue Ridge, as far as the confluence of the Kentucky and Ohio rivers. The treaties did not relinquish any claims by the Shawnee or other tribes to land north of the Ohio River. Land speculators seeking the opportunity to sell land north of the river received no direct benefit from the 1768 treaties.

in separate treaties, William Johnson and John Stuart obtained approval from the Iroquois and Cherokee for colonial settlement of lands south of the Ohio River

Source: National Park Service, 1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix

the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix assumed the Iroquois could cede land south of the Ohio River, all the way west to the mouth of the Tennessee ("Cherokee") River

Source: National Park Service, 1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix

the Cherokee signed the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor and the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, expanding the territory controlled by Virginia and reducing the extent of the Cherokee hunting grounds

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Proclamation of 1763 and subsequent treaties that adjusted the line of settlement did not succeed in creating a buffer zone that reassured the Native American tribes. In 1772 William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, wrote to the Secretary of State in London:16

- ...the back inhabitants particularly those who daily go over the Mountains of Virginia employ much of their time in hunting, interfere with them therein, have a hatred for, ill treat, Rob and frequently murder the Indians, that they are in general a lawless sett of People...

Resolution of claims by other Native Americans required further fighting. Raids by the Shawnee and others continued in western Virginia, and settlers in the Kentucky region had to build fortified "stations" for protection.

Cornstalk, leader of the Shawnee, recognized the overwhelming military superiority of the British forces after the Native Americans were defeated in Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763. Cornstalk advocated for peacefully adjusting to expanding settlement, but failed in his efforts. Both colonists and Native Americans created incidents that inflamed the other side. In two famous incidents, Daniel Boone's son James was captured and tortured to death in 1773, while the family of the Mingo leader Logan was murdered while peacefully visiting a cabin on the Ohio River (the "Yellow Creek Massacre").

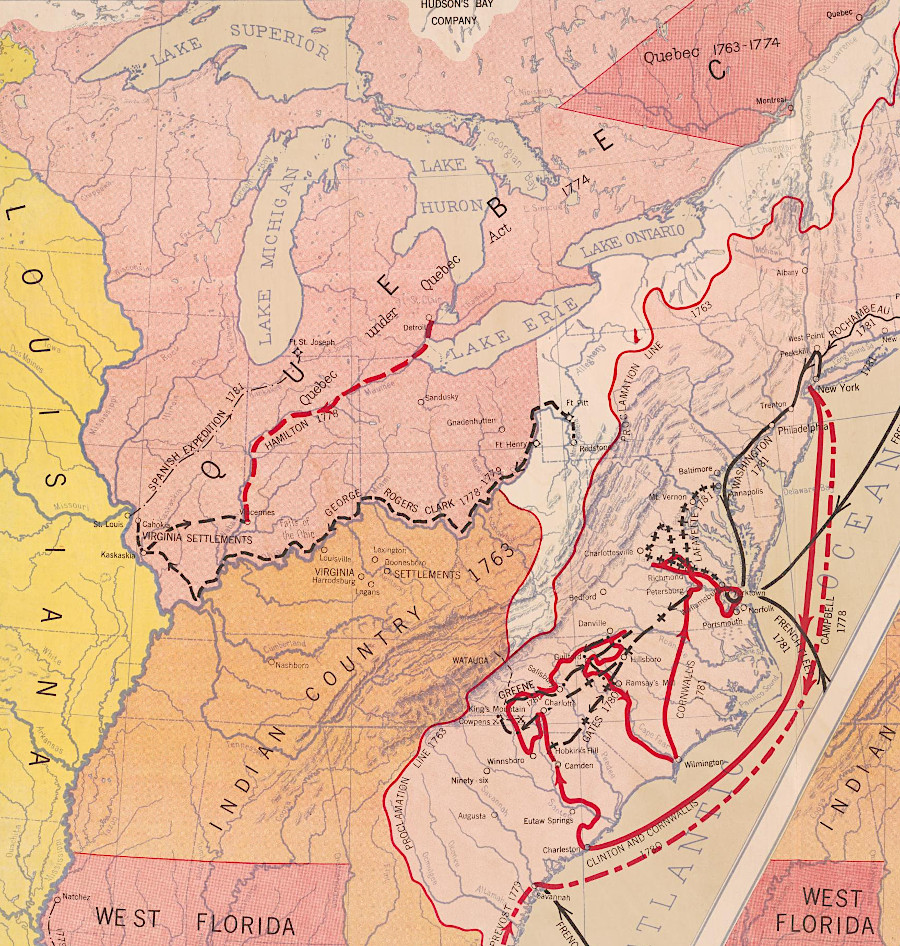

In 1774, after the "Boston Massacre," King George III extended the boundaries of the province of Quebec down to the Ohio River. The Quebec Act of 1774 eliminated any opportunity for the Virginia governor and General Assembly to finalize land claims north of the Ohio River. British officials avoided creating conflict with the Iroquois, Shawnee, and Cherokee by limiting the extended boundary of Quebec to just the Ohio River. The 1774 Quebec Act did not affect claims of the Iroquois in New York, or of any Native American group to lands south of the Ohio River.

The king's decision failed to intimidate the Virginia gentry or other rebellious colonial leaders. Based on the Cherokee land cessions in the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, the General Assembly had split Augusta County in 1770 to form Botetourt County. In 1772, the colonial legislature carved Fincastle County out of Botetourt County. In 1774, Virginia's colonial leaders split Augusta County, creating the "District" of West Augusta rather than the "county" of West Augusta to avoid a direct confrontation with the Proclamation of 1763.

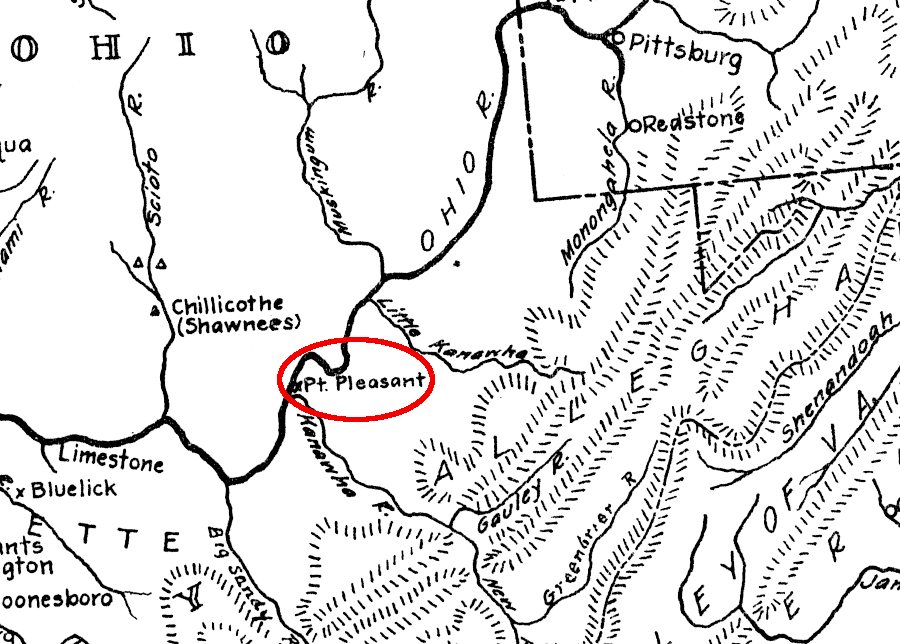

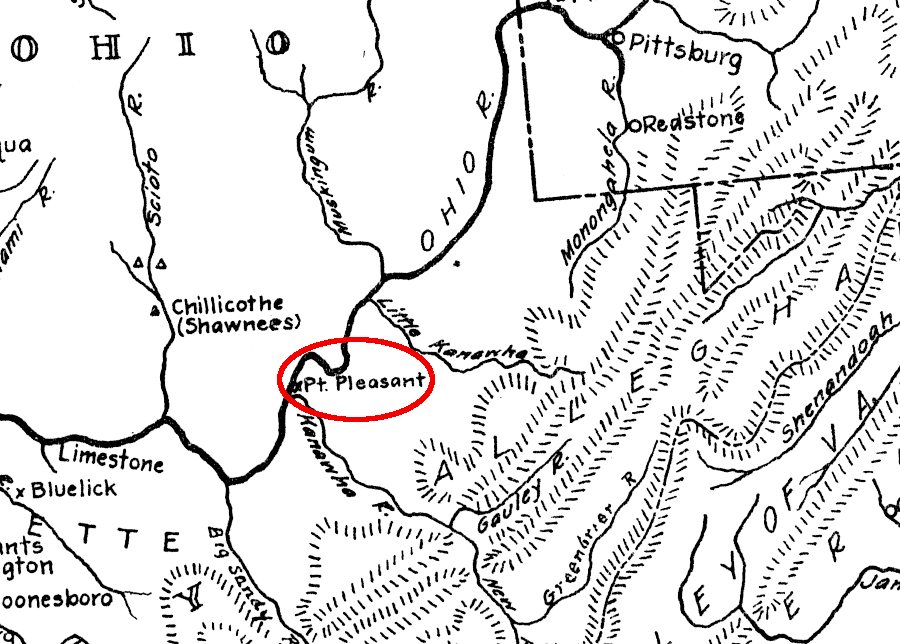

Also in 1774, Governor Dunmore sought to create a distraction from the rebellious debates in Williamsburg and to strengthen colonial commitment to Great Britain. With support from the General Assembly, Lord Dunmore mobilized county militias (no British regiments were involved) and launched a two-pronged attack into Shawnee-controlled territory.

Dunmore led one wing of the army, assembling it at Fort Pitt. Before that wing descended the Ohio River, the other part of the Virginia army led by Andrew Lewis defeated the Shawnee at Point Pleasant. Cornstalk then negotiated the Treaty of Camp Charlotte to end Dunmore's War. In that 1774 treaty, the Shawnee ceded their claims to lands south of the Ohio River. Dunmore did not demand any rights to settle on any land claimed by the Shawnee, beyond the territory was already included in the 1769 Treaty of Fort Stanwix.

the Virginia militia's victory at Point Pleasant was followed by the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, in which the Shawnee agreed to allow colonial settlement south of the Ohio River

Source: West Virginia Archives and History, Teacher Resources, Map of Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern States during the Revolutionary War Era

Dunmore had acted inconsistently with the intent behind the Proclamation of 1763. In his official report, he made excuses for strengthening the fort at the Forks of the Ohio River:17

- The Policy of Government, respecting the back Country, and the Measures pursued in consequence of it, which your Lordship has been at the pains of explaining to me, I cannot, as you rightly observe, be ignorant of, and I might Suppose your Lordship informed that I was not ignorant of them...`

- ...In regard to the Fort of Pittsburg, this, your Lordship has Seen in my relation, was done by my order: but if it be seen as it really was, in the light of a temporary work for the defence of a Country, and its terrified Inhabitants in a time of imminent danger, I presume it will appear very different from reestablishing a Fort which had been demolished by the Kings express orders, as if this Act of mine had been contrary to or in disregard of His Majesty's orders:

- And My Lord, I fear, that it must be owing to the unfavourable opinion which your Lordship conceives of my Administration, that it did not readily occur to your Lordship, that the distress and alarm, of which you were apprised at the Same time, however they were occasioned, required that Step, and accounted for it.

In London, British officials were not as accommodating as Governor Dunmore. Under Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Commissioners of Trade and Plantations had opposed grants west of the 1763 line until he was replaced by the Earl of Dartmouth. After the Privy Council indicated it could support the proposed new colony of Vandalia in 1773, the commissioners relaxed their opposition. Still, Dunmore took a career-ending risk to go to war in order to assist Virginians speculating on lands west of the Allegheny Front.18

Vandalia was tentatively approved in London but the grant was never formalized. That threat to the land grants obtained by the Ohio Company, Greenbrier Company, and Loyal Land Company was blocked by inertia as well as by opposition from British officials. Settling the "Indian Reserve" west of the Allegheny Mountains was not likely to create a new colony of loyalists who wanted to stay aligned with King George III.

A significant barrier to the Virginia land speculators was the Quebec Act of 1774, one of the "intolerable" acts passed by Parliament in reaction to the Boston Tea Party. The Quebec Act, approved by George III on June 22, 1774 and in effect starting May 1, 1775, revoked the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Great Britain recognized that the original plan based on the proclamation would not succeed. England, Scotland and Wales could not send enough colonists to establish an English-speaking, Anglican culture in Quebec that would assimilate and replace the existing French-based culture. The suppression and anti-Catholic tactics used against the conquered people in Ireland would not work in Canada.

Instead, the Privy Council chose to accommodate the residents in Quebec. There was a need to placate them in 1774, as the Americans in 13 colonies south of the St. Lawrence River were becoming rebellious.

The Quebec Act incorporated into the Province of Quebec all lands not within the Indian Reserve or the colonies of East Florida, West Florida. Catholics within the expanded boundaries of Quebec were granted religious freedom, but from the Virginia point of view the greatest problem was the increased legal impediment to acquiring title to western lands.

lands claimed by the Cherokee in the Tennessee River watershed were placed in an Indian Reserve and excluded from colonial settlement, according to the Proclamation of 1763

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, British Possessions after the Quebec Act, 1774 (Plate 46a, digitized by University of Richmond)

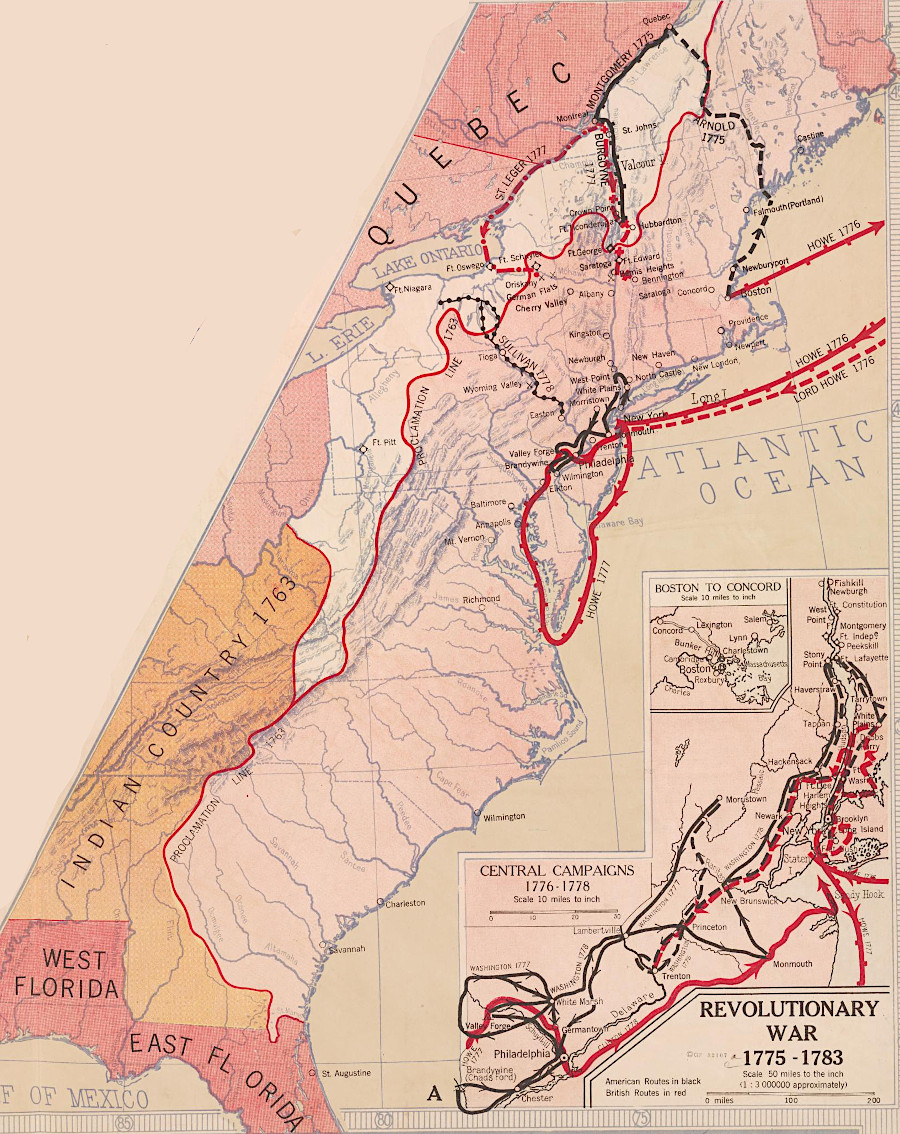

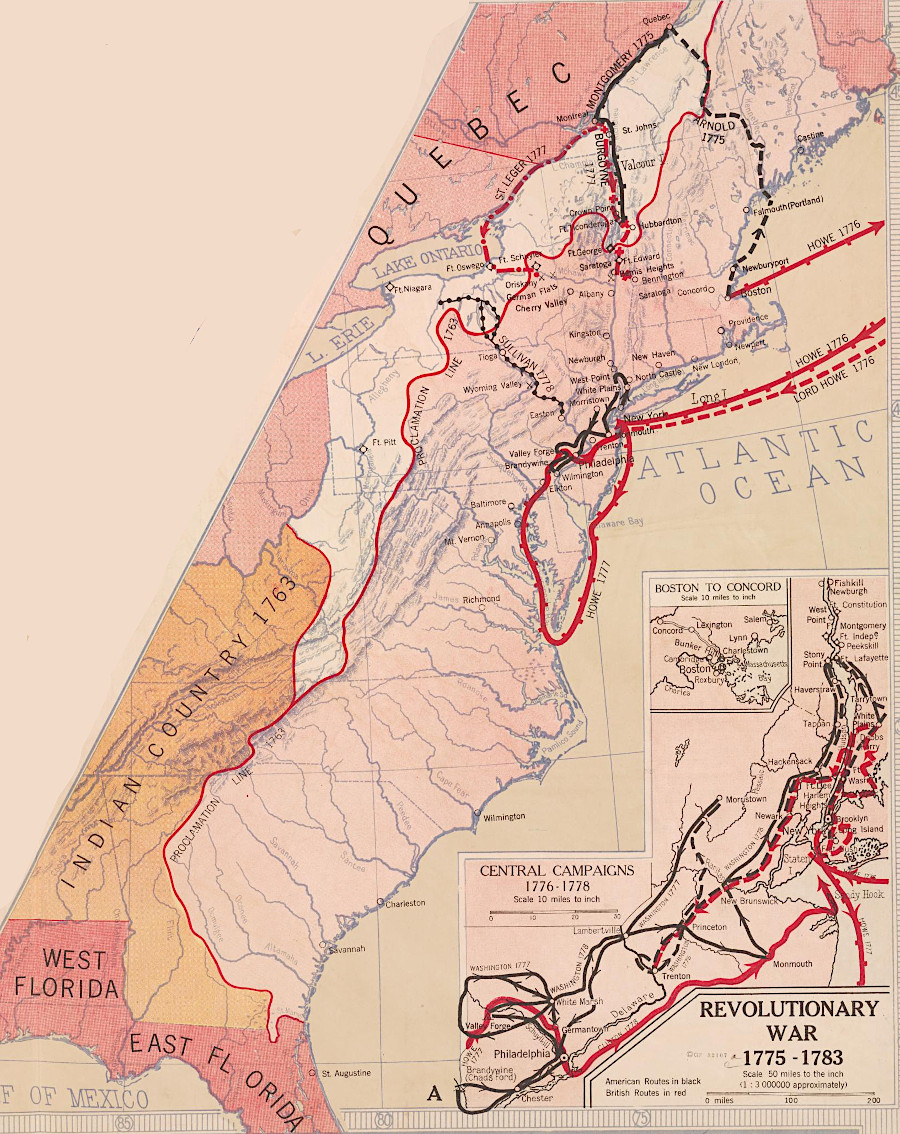

in 1774, British officials extended Quebec to include Virginia's claims to land north of the Ohio River

Source: Library of Congress, Revolutionary War, 1775-1783 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1917)

In 1775, Richard Henderson totally ignored the Proclamation of 1763 when he negotiated the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals with the Cherokee. The sale of the Cherokee claims to much of the Kentucky region theoretically extinguished Cherokee claims and authorized colonial settlement on 20 million acres.

From a legalistic perspective, as viewed by the British, the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor, the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, the 1774 Treaty of Camp Charlotte, and the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals pushed the Proclamation of 1763 boundary westward. Those treaties allowed settlement far beyond the Eastern Continental Divide in what today is southwestern Virginia, West Virginia, most of Kentucky, and much of Tennessee and Ohio.

However, raids from Native American groups living north of the Ohio River continued to limit the ability of colonists to occupy western lands. As predicted by Cherokee leader Dragging Canoe at the signing of the 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, Kentucky was a "dark and bloody ground." Ohio also remained a zone of conflict. Cornstalk visited a Virginia fort at Point Pleasant in 1777 to renew the peaceful status of the Shawnee, but he was seized and murdered.19

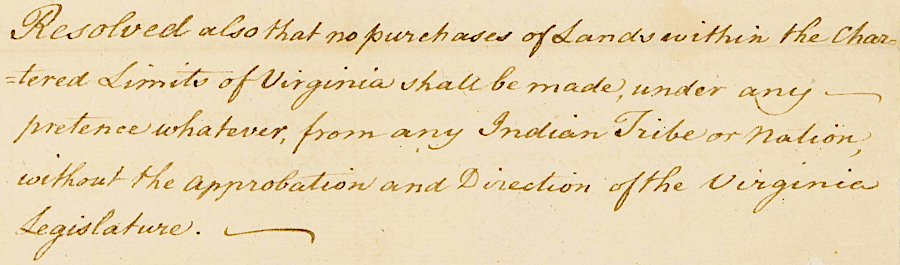

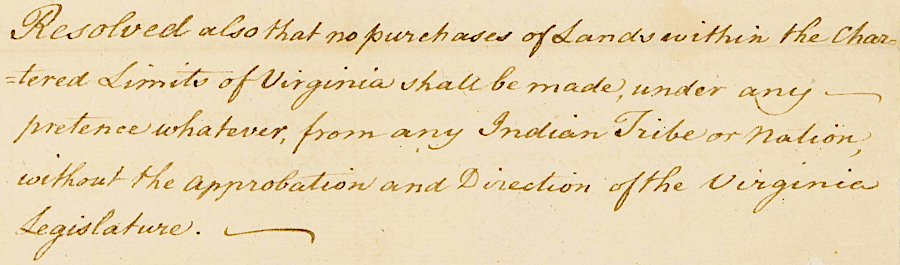

In 1776, soon after declaring independence, the Fifth Virginia Convention banned private individuals from negotiating land purchases from Native American tribes.

the revolutionaries taking control of Virginia government in 1776 maintained the ban on private land purchases that was established in the Proclamation of 1763

Source: Library of Virginia, Resolution regarding claims to Indian lands, 1776 June 24

1779 the Virginia General Assembly mimicked the policy used by King George III in 1763 to block settlement of western lands. In order to maintain peace with the Native Americans living there, the legislature determined (emphasis added):20

- WHEREAS, although no lands were allowed by law to be entered or warrants to be located on the north west side of the Ohio river, until the farther order of the general assembly, several persons are notwithstanding removing themselves to and making new settlements on the lands upon the north west side of the said river, which will probably bring on an Indian war with some tribes still in amity with the United American States, and thereby involve the commonwealth in great expense and bring distress on the inhabitants of our western frontier: Be it declared and enacted, That no person so removing to and settling on the said lands on the north west side of the Ohio river, shall be entitled to or allowed any right of preemption or other benefit whatever, from such settlement or occupancy; and the governour is hereby desired to issue a proclamation, requiring all persons settled on the said lands immediately to remove there from, and forbidding others to settle in future, and moreover with the advice of the council, from time to time, to order such armed force as shall be thought necessary to remove from the said lands, such person or persons as shall remain on or settle contrary to the said proclamation:

- Provided, That nothing herein contained shall be construed in any manner to injure or affect any French, Canadian, or other families, or persons heretofore actually settled in or about the villages near or adjacent to the posts reduced by the forces of this state.

In 1783, George Washington endorsed an American equivalent of the Proclamation of 1763 to separate Native Americans and settlers:21

- To suffer a wide extended Country to be overrun with Land jobbers-Speculators, and Monopolizers or even with scatter'd settlers is, in my opinion, inconsistent with that wisdom & policy which our true interest dictates, or that an enlightned People ought to adopt; and besides, is pregnant of disputes, both with the Savages, and among ourselves, the evils of which are easier, to be conceived than described; and for what? but to aggrandize a few avaricious Men to the prejudice of many and the embarrassment of Government. For the People engaged in these pursuits without contributing in the smallest degree to the support of Government, or considering themselves as amenable to its Laws, will involve it by their unrestrained conduct, in inextricable perplexities, and more than probable in a great deal of Bloodshed...

- As the Country, is large enough to contain us all; and as we are disposed to be kind to them and to partake of their Trade, we will from these considerations and from motives of Compn, draw a veil over what is past and establish a boundary line between them and us beyond which we will endeavor to restrain our People from Hunting or Settling, and within which they shall not come, but for the purposes of Trading, Treating, or other business unexceptionable in its nature.

The Confederation Congress did mimic the British government's 1763 ban on western expansion. It issued an American proclamation 20 years after King George III (emphasis added):22

- ...whereas it is essential to the welfare and interest of the United States as well as necessary for the maintenance of harmony and friendship with the Indians, not members of any of the states, that all cause of quarrel or complaint between them and the United States, or any of them, should be removed and prevented: Therefore the United States in Congress assembled have thought proper to issue their proclamation, and they do hereby prohibit and forbid all persons from making settlements on lands inhabited or claimed by Indians, without the limits or jurisdiction of any particular State, and from purchasing or receiving any gift or cession of such lands or claims without the express authority and directions of the United States in Congress assembled.

- And it is moreover declared, that every such purchase or settlement, gift or cession, not having the authority aforesaid, is null and void, and that no right or title will accrue in consequence of any such purchase, gift, cession or settlement.

The American Revolution completely eliminated British authority to dictate the terms of American settlement on western lands. Great Britain delayed its withdrawal of garrisons in the territory it surrendered and stimulated additional Native American resistance, but British officials lost their influence in awarding/blocking land grants or determining where Americans could settle.

Virginia relinquished its claim in 1784 when the Continental Congress accepted the cession of the Northwest Territory in 1784. Virginia leaders still remained deeply involved in shaping the settlement pattern for the lands west of the old Proclamation of 1763 line.

Thomas Jefferson wrote the Ordinance of 1784, which proposed the creation of new states from the Southwest Territory and Northwest Territory. Jefferson assumed Native American claims would be acquired through purchase, legitimizing settlement. He proposed creating 10 new states, giving them equal status with existing states once they gained enough population to enter the union.

The Confederation Congress approved the ordinance, but did not implement it. The 13 original states had little desire to dilute their authority, or see residents flee to the west without paying their debts and leave fewer people behind to carry the tax burden.

The survey-before-sale approach was adopted in the Land Ordinance of 1785, facilitating actual transfer of lands. Passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 finally led to the creation of new states. The Proclamation Line, as declared by the Confederation Congress in 1783, did not result in the United States creating permanent colonies with constrained sovereignty on the western side of the line.23

After the American Revolution, the new national government continued the British approach of creating reserves for Native Americans. It signed treaties that defined boundaries defining lands reserved for Native Americans, failed to enforce the barriers to settlement, and then revised treaty boundaries.

The 1785 Treaty of Fort McIntosh established a new boundary with a reserve between the Cuyahoga and Maumee rivers for the Wyandot, Delaware (Lenape), Chippewa (Ojibwa), and Ottawa, while reserving a portion of the Northwest Territory "to the Wiandot and Delaware nations, to live and to hunt on, and to such of the Ottawa nation as now live thereon.."

After "Mad Anthony" Wayne's victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the 1795 Treaty of Greenville redefined that line. Neither treaty protected the reserved lands for long.

the 1785 Treaty of Fort McIntosh was intended to release eastern and southern Ohio for American settlement

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Compact of 1802, after the Yazoo Land Fraud, the Federal government assumed Georgia's western land claims. President Thomas Jefferson schemed to acquire Native American lands east of the Mississippi River peacefully. He wrote to a trusted ally in 1803:24

- ...by giving them effectual protection against wrongs from our own people, the decrease of game rendering their subsistence by hunting insufficient, we wish to draw them to agriculture, to spinning & weaving... when they withdraw themselves to the culture of a small piece of land, they will percieve how useless to them are their extensive forests, and will be willing to pare them off from time to time in exchange for necessaries for their farms & families...

- ...we shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good & influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop th[em off] by a cession of lands

Georgians were frustrated at the Federal government's slow pace of buying the land and opening it to settlement. General Andrew Jackson took advantage of the War of 1812 to invade Native American territory in the southeast and even Spanish-controlled Florida. After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, Jackson and other American negotiators forced the Mikasuki (Muskogee)-speaking tribes to sign a series of treaties between 1816-20.

Under pressure, Creek leaders who had fought as allies of Jackson - and were critical to his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend - were forced to cede their territory and migrate westward across the Mississippi River. Signing the Treaty of Fort Jackson and other cessions allowed the tribes to maintain sovereignty while abandoning their homeland. The alternative choice was to remain within what became Alabama and western Georgia, and attempt to assimilate into American society.

the National Park Service now owns the site of the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend, after which Creek chiefs were forced to cede nearly half of their land to the United State

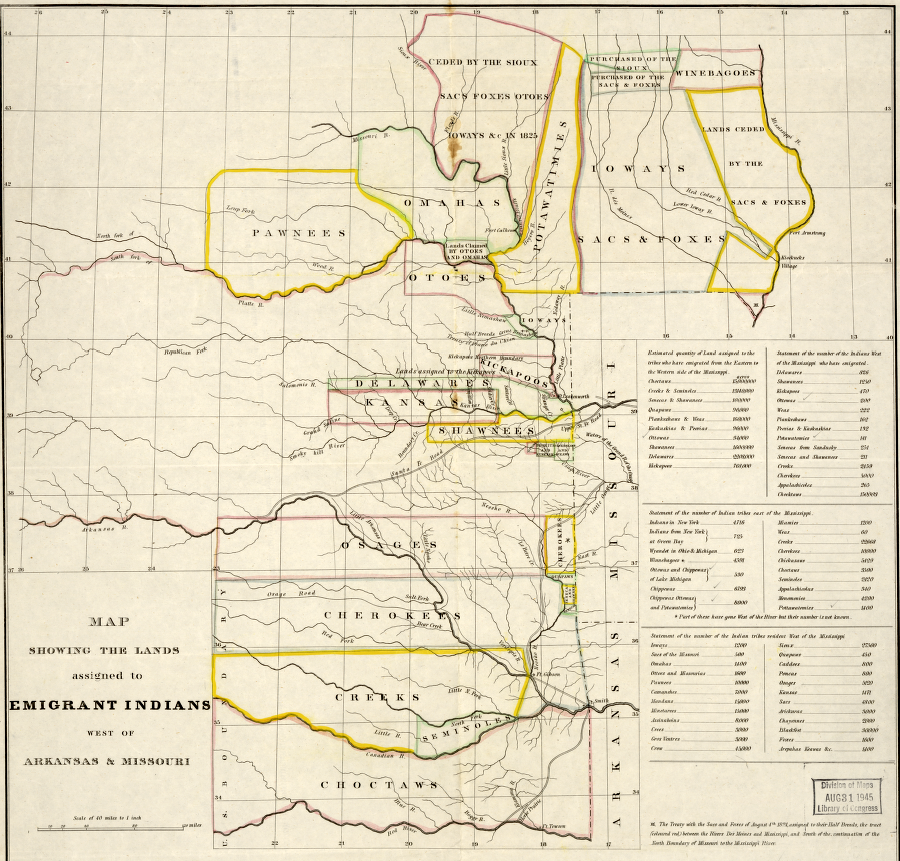

The final chapter in the settlement of the lands between the Eastern Continental Divide and the Mississippi River came when President Andrew Jackson pressed Congress successfully to approve the Indian Removal Act in 1830. A year earlier, gold was discovered in Cherokee-controlled territory. Jackson was anxious to accommodate Georgia officials in part because South Carolina was looking for allies to declare that a state could nullify the 1828 tariff as unconstitutional, and even secede if a state found a Federal law to be oppressive. To isolate South Carolina and force it to accept continued Federal authority, President Jackson gave Georgia settlers what they wanted most: access to Native American land.

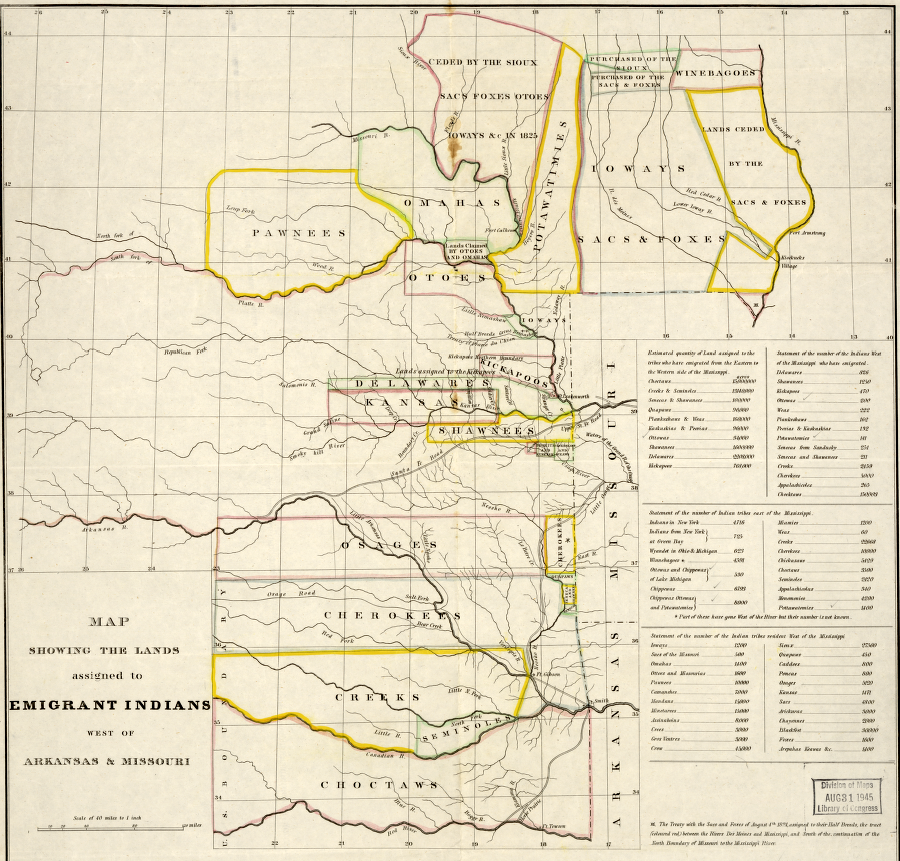

The removal of the Five Civilized Tribes in the south (Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee) resulted from that law, including the Cherokee expulsion via the "Trail of Tears." Northern tribes, including the Shawnees, Wyandots (Hurons) and Ottawas, were also displaced west of the Mississippi River. The Sauk and Fox returned to Illinois to hunt in 1832, but were expelled again after the Black Hawk War.

The Choctaw were the first to be removed to the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Not all chose to go, and today the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians have a reservation in east central Mississippi. Similarly, not all the Cherokee joined the Trail of Tears. With the help of an ally, they purchased the rights to land. The Qualla Boundary in western North Carolina is still the home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

The Third Seminole War in 1856-58 triggered the last forced deportation from the southeastern United States prior to the Civil War, but not all Native Americans in Florida were caught and expelled. The Seminole Tribe of Florida organized in 1957, established a Tribal Roll to documents its members, and pioneered use of bingo and modern casinos to generate tribal revenue.

Mikasuki-speaking Creeks avoided capture by retreating into the Everglades. The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida was reestablished in 1962, and they occupy one of many reservations of different tribes that still exist as organized groups east of the Mississippi River.25

the Indian Removal Act of 1830 pushed across the Mississippi River the boundary that was defined in the Proclamation of 1763, creating an Indian Reserve to limit conflicts between settlers and Native Americans"

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the lands assigned to emigrant Indians west of Arkansas and Missouri.

Links

the Proclamation Line of 1763 defined land west of the Eastern Continental Divide as an "Indian Reserve"

Source: Department of State, Milestones: 1750-1775 - Proclamation Line of 1763, Quebec Act of 1774 and Westward Expansion

the Virginia elite saw potential acquisition of land grants blocked by the reservation of lands west of the Proclamation Line of 1763

Source: Library of Congress, Bowles's new pocket map of the United States of America (1783)

References

1. "'Why Does it Have to Be Slaveholders That We Unite Around?'," New York Times, October 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-woody-holton.html (last checked October 23, 2021)

2. "1619: Laws enacted by the First General Assembly of Virginia," Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/1619-laws-enacted-by-the-first-general-assembly-of-virginia (last checked February 8, 2015)

3. "Narrative History," in A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century, Colonial National Historical Park (National Park Service), December 2005 http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/jame1/moretti-langholtz/chap4.htm (last checked October 2, 2011)

4. "Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, George Washington Birthplace National Monument," National Park Service, 2009,

p. 79, http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/gewa/gewa_eoa.pdf (last checked October 2, 2011)

5. "Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, George Washington Birthplace National Monument," p. 86, https://www.si.edu/object/ethnographic-overview-and-assessment-george-washington-birthplace-national-monument-kathleen-j:siris_sil_967478 (last checked December 5, 2025)

6. Helen C. Rountree (ed), Powhatan Foreign Relations, 1500-1722, University Press of Virginia, 1993, p. 195-196, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Powhatan_Foreign_Relations_1500_1722/64ZiQgAACAAJ; William Waller Hening, The Statutes At Large, Volume 1, pp.467-468, March 1657-1658, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hw2scp?urlappend=%3Bseq=515%3Bownerid=27021597765515617-535; Paul W. Gates, History of public land law development, Public Land Law Review Commission, pp.33-24, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106000891595?urlappend=%3Bseq=53%3Bownerid=9007199266889467-57 (last checked December 5, 2025)

7. "Reasons and Motives for the Albany Plan of Union, [July 1754]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-05-02-0109; "Albany Plan of Union, 1754," US State Department, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/albany-plan (last checked June 30, 2025)

8. "Treaty of Paris, 1763," Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations, US Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris (last checked August 17, 2016)

9. "The Road to Independence: Virginia 1763-1783," Virginia Department of Education, 1976, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/30058/pg30058-images.html; "Pontiac's Rebellion," Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/pontiacs-rebellion#3; "Pontiac's War," The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 4, 2015, https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pontiacs-war-feature (last checked August 6, 2025)

10. "Proclamation Line of 1763," Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/proclamation-line-of-1763; "Proclamation Line of 1763, Quebec Act of 1774 and Westward Expansion," US State Department, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/proclamation-line-1763 (last checked August 2, 2025)

11. Proclamation of 1763, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/proc1763.htm; "Royal Proclamation of 1763," The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763; "Minutes of the Southern Congress at Augusta, Georgia," Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr11-0084 (last checked August 8, 2025)

12. Mark G. Hanna, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740, The University of North Carolina Press, 2015, p.33, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pirate_Nests_and_the_Rise_of_the_British/RSMUCAAAQBAJ (last checked March 24, 2020)

13. Proclamation of 1763, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/proc1763.htm (last checked January 26, 2025)

14. "The Road to Independence: Virginia 1763-1783," Virginia Department of Education, 1976, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/30058/30058-h/30058-h.htm (last checked November 24, 2017)

15. letter, George Washington to William Crawford, September 21, 1767, in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, John C. Fitzpatrick (editor), in "George Washington: Surveyor and Mapmaker," Library of Congress, https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/gmdhtml/gwmaps.html (last checked August 18, 2016)

16. "1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/1768-boundary-line-treaty-of-fort-stanwix.htm; "'The uncommon increase of Settlements in the back Country': Sir William Johnson Watches the Settlers Invade Indian Lands," History Matters, https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5710 (last checked August 8, 2025)

17. "Affairs In Virginia; The Indian Expedition," Lord Dunmore's official report to the Secretary of State Lord Dartmouth, December 24, 1774, in Reuben Gold Thwaites, Documentary history of Dunmore's war, 1774 , Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905, p.369, p.388, https://archive.org/details/documentaryhist00thwarich; "1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/1768-boundary-line-treaty-of-fort-stanwix.htm (last checked August 6, 2025)

18. "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?," West Virginia History, West Virginia Archives and History, Volume 40, Number 4 (Summer 1979), http://www.wvculture.org/HISTORY/journal_wvh/wvh40-4.html (last checked August 16, 2016)

19. "Treaty of Camp Charlotte," Touring Ohio, http://touringohio.com/history/camp-charlotte.html (last checked August 18, 2016)

20. "An Act for more Effectually Securing to the Officers and Soldiers of the Virginia line, the lands reserved to them, for discouraging present settlements on the north west side of the Ohio river, and for punishing persons attempting to prevent the execution of land office warrants," Military Bounty Warrants 1779, Kentucky Secretary of State, https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/legislation/Documents/Military%20Bounty%20Warrants%201779.pdf; "Resolution regarding claims to Indian lands, 1776 June 24," Library of Virginia, https://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:443/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3850063

(last checked August 14, 2025)

21. George Washington, "From George Washington to James Duane, 7 September 1783," National Archives - Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11798 (last checked July 9, 2019)

22. "Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 - Monday, September 22, 1783," Library of Congress, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:1:./temp/~ammem_cvCS:: (last checked April 25, 2018)

23. "Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789," Library of Congress, April 23, 1784, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/bdsdcc:@field(DOCID+@lit(bdsdcc13401)); George William Van Cleve, We Do Not Have a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution, University of Chicago Press, 2017, pp.139-140, https://books.google.com/books?id=NbbXAQAACAAJ (last checked April 25, 2018)

24. Thomas Jefferson, "From Thomas Jefferson to William Henry Harrison, 27 February 1803," National Archives - Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-39-02-0500; Sarah H. Hill, "Cherokee Indian Removal," Encyclopedia of Alabama, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1433 (last checked July 9, 2019)

25. Sean Wilentz, Andrew Jackson, Times Books, 2005, p.36, https://books.google.com/books?id=1GhZl6KhM4cC; "History," Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, http://www.choctaw.org/aboutMBCI/history/index.html; "Contemporary," Museum of the Cherokee Indian, https://www.cherokeemuseum.org/archives/era/contemporary; "Seminoles Today," Seminole Tribe of Florida, https://www.semtribe.com/STOF/history/seminoles-today; "Frequently Asked Questions," Seminole Tribe of Florida, https://www.semtribe.com/STOF/history/faq---history; "History," Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, https://tribe.miccosukee.com/ (last checked July 9, 2019)

most of the American Revolution battles were fought east of the 1763 Proclamation Line

Source: Library of Congress, Revolutionary War, 1775-1783 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1917)

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places