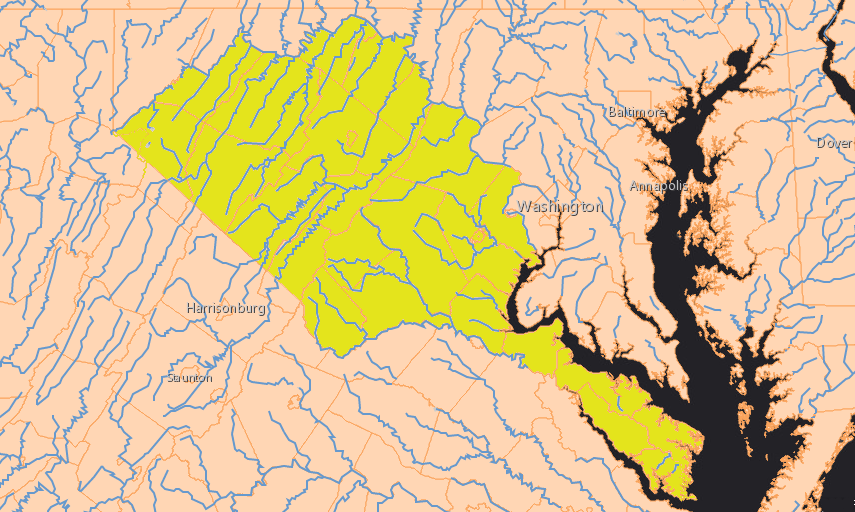

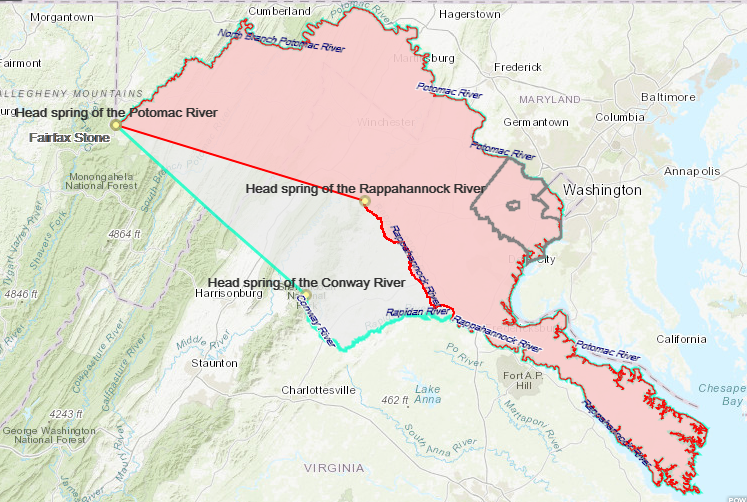

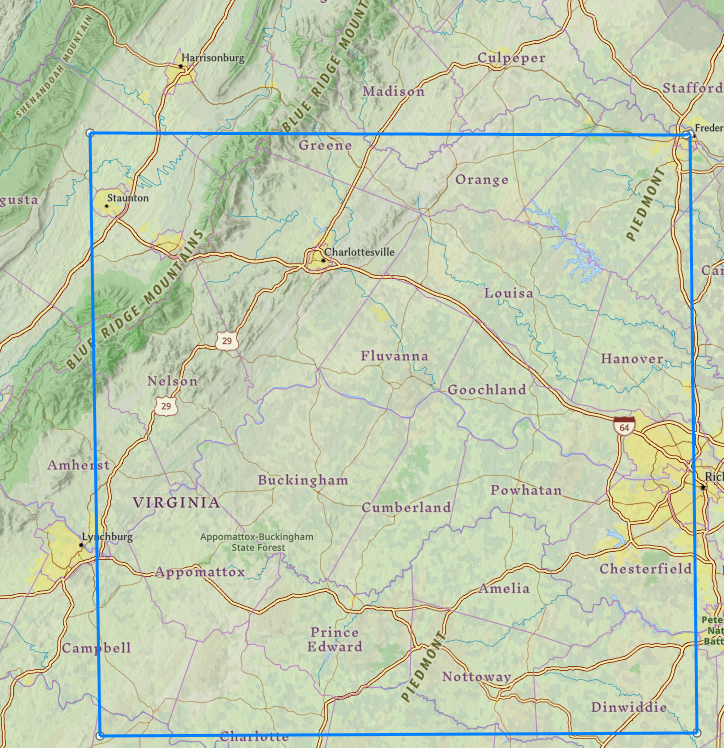

the final boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, defined 97 years after the initial grant in 1649, included 5.2 million acres

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the final boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, defined 97 years after the initial grant in 1649, included 5.2 million acres

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Fairfax Grant in Virginia was created as a result of the English Civil War in the mid-1600's. It was a political payoff to allies of King Charles II, who was organizing his ascension to the throne after his father Charles I was executed.

The Culpeper family obtained, consolidated, and retained the grant during the eras of Charles II, James II, and the rule of William and Mary. The Fairfax name is associated with the grant today because a daughter of a Culpeper married a Fairfax in 1690, and their son ended up owning all the shares granted initially in 1649.

The oldest son of that marriage, Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax, obtained 100% control partly through inheritance and partly through marriage. What today is called the Fairfax Grant acknowledges his success in maneuvering throughout the 1730's and 1740's to assert his land claim, blocking efforts of the colonial government to extinguish or limit the territory that would be included within the boundaries.

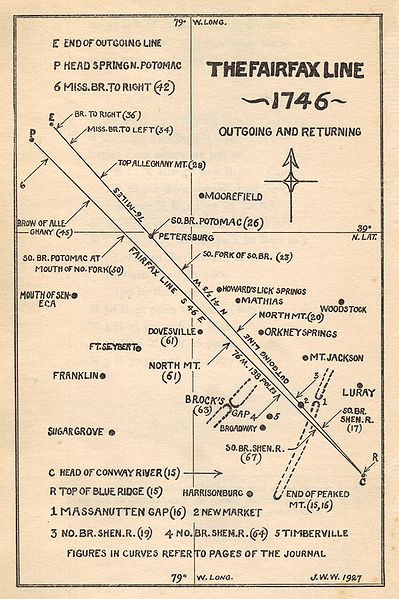

Virginia officials in Williamsburg disputed the right of land agents employed by Lord Fairfax to sell land in the Shenandoah Valley. That triggered an official survey of the 1649 grant boundaries. Decisions in London finally defined the extent of the Fairfax Grant in 1745, and the line between the headsprings of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers was surveyed officially a year later.

The original basis for the grant dates back to the English Civil War, which was won by the Parliamentary party under Oliver Cromwell. John Culpeper was on the side of the king, Charles I. He elevated Culpeper to the peerage in 1644 and made him the first Baron Colepeper of Thoresway, or John First Lord Culpeper.

Charles I was the loser in the civil war. The victorious Puritans executed the king on January 30, 1649 (1648, using the Old Style calendar) and controlled England for a decade. After the king's execution, the son of Charles I declared himself to be King Charles II, but had to flee to France with his few supporters. One of those supporters was John First Lord Culpeper, who stayed an ally on the royalist side.

While in exile in France, Charles II had limited resources to reward his key supporters and retain their allegiance. The king-in-exile did claim that he retained the right to govern the colonies across the Atlantic Ocean in North America, and could dispose of his land there.

In September, 1649 Charles II used that authority and granted all the land between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers in the Virginia colony to seven supporters: Sir John Culpeper (1st Baron of Thoresway); Ralph Lord Hopton, Baron of Stratton; Henry Lord Jermyn, Baron of St. Edmundsbury; Sir John Berkeley; Sir William Morton; Sir Dudley Wyatt; and Thomas Culpeper (cousin of Sir John Culpeper).1

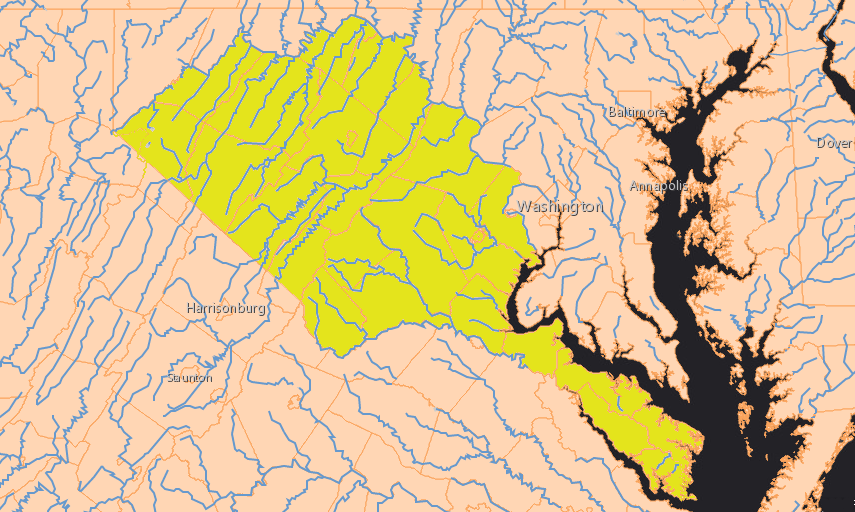

Charles II was following an example set by his father. After Charles I revoked the charter of the Virginia Company in 1624, he waited for just five years before issuing a new massive land grant in North America. The king gave to Sir Robert Heath all the land between 21° and 36° parallels of latitude plus the Bahamas, a total of roughly 500,000 square miles (320,000,000 acres). The grant was increased in size in 1665 when the northern boundary was raised to the 36° 30’ parallel of latitude and the southern boundary lowered to the 29° parallel. Heath was unable to settle his land as the English Civil War developed, so the land was available for a later grant by King Charles II in 1663.

the 320,000,000 acre grant in 1629 to Sir Robert Heath by Charles I dwarfs the size of the 5,200,000 acre 1649 Fairfax Grant by Charles II

Source: South Carolina Historical Society, Troublesome Boundaries: Royal Proclamations, Indian Treaties, Lawsuits, Political Deals, and Other Errors Defining Our Strange State Lines

While in exile in France, Charles II devoted assets with immediate value such as jewels to the immediate challenge of gaining the throne in England. Land grants were strategic gifts, with long-term benefits.

It was easy for King Charles II to transfer ownership of a large chunk of Virginia in 1649 to gain support. That land was far away and generating no income for him. Charles II needed loyalty for fighting the English Civil War far more than he needed long-term revenue from a colony. After the English Civil War ended and he took the throne in 1660, Charles II made another large grant of land south of Virginia. He made eight men "proprietors" of Carolina in 1663, setting the initial boundary between that grant and the royal colony of Virginia at the 36° parallel of latitude.

As one scholar has noted:2

granting land in Virginia in 1649 helped Charles II retain allies and be restored to the English throne in 1660

Source: National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 531, King Charles II (by John Michael Wright, circa 1660-1665)

The grant helped solidify support for the royalist side, because it would have value only if Charles II became king in fact as well as in name. The king's seven supporters would not gain legal title to all the land between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers if Charles II was defeated, so the gift reduced the chances of someone shifting allegiance to the Parliamentary side.

The transfer of ownership of the entire Northern Neck affected development of Virginia until the American Revolution. When the English arrived in 1607, Northern Virginia was outside the boundaries of Tsenacomoco, the area controlled by Powhatan. The 1649 grant made Northern Virginia "different" in the colonial period, long before the modern regional classifications of NOVA (Northern Virginia) and ROVA (Rest of Virginia).

The seven grantees knew the land in Virginia had the potential to be valuable in future years, but had very little understanding of the location of the grant. It took almost 100 years before a descendant of Sir John Culpeper, Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax, converted the king's gift into clear title. That 1649 gift from Charles II ended up as the biggest successful land speculation in Virginia, ultimately involving 5.2 million acres.

Fairfax Grant, 1747 (after resolution of Fairfax v. Virginia by Privy Council in 1745)

Source: Library of Congress, A survey of the northern neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the Rt. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the Bay of Chesapoyocke and between the rivers

Rappahannock and Potowmack:With the courses of the rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia, as surveyed according to order in the years 1736 & 1737

For the first decade after Charles II's gift, the value of the grant appeared to be close to zero. The seven allies who received the grant were on the losing side of the English Civil War throughout the 1650's.

The colonial officials in Virginia were also on the losing side. Like Sir John Culpeper, Virginia Governor William Berkeley and the colony's House of Burgesses declared loyalty to King Charles II, after King Charles I was executed. The political elite in Virginia and the governor feared the Parliamentary government in England (the "Commonwealth") would confiscate their land or block their ability to obtain new grants.

In addition, Parliament passed new laws that disrupted Virginia's economy. The Navigation Acts in the 1650's excluded the Dutch from trading in Virginia. Banning Dutch ships reduced competition for purchasing Virginia's tobacco. Monopoly control by English shippers led to lower prices for the colony's primary export, and higher costs for goods imported from Europe and the Caribbean.3

Parliament sent a fleet across the Atlantic Ocean and took control over the Virginia colony in 1652. Governor William Berkeley retired to his mansion at Green Springs and a Puritan, Richard Bennett, took his place. Existing land titles of the royalists in Virginia were not challenged by Governor Bennett, but the 1649 Northern Neck land grant was ignored.

No matter which side was in control in London, leaders of the colony in Jamestown felt no obligation to seven "proprietors" across the ocean with just a paper claim to a large percentage of Virginia. Prior to the arrival of the Parliamentary fleet, Governor William Berkeley and the General Assembly - still loyal to Charles II - had created Lancaster County in 1651. In 1653 the General Assembly created two new counties in the Northern Neck. Northumberland County was split and Westmoreland County formed in 1653. In 1656, Lancaster County was divided and a new county created named Rappahannock (now Essex and Richmond counties).4

In England, Parliament did seize the property of the king's allies, including the estates of Sir John Culpeper. Charles II established his right to that seized property after the Restoration in 1660, but Sir John Culpeper died soon afterwards. His son Thomas, the Second Lord Culpeper, then inherited the significant Culpeper claims for repayment of 12,000 pounds from the king. In addition, he inherited his father's 1/6th share of the Northern Neck grant.

In 1669, four of the Northern Neck proprietors (but not the heirs of the two Culpepers) negotiated a 21-year renewal of the grant from Charles II. That renewal clarified the claim to land in Virginia was still valid despite the confusion of the English Civil War, but the land was still far away across the Atlantic Ocean. Through the headrights process based in Jamestown, colonists were acquiring land within the boundaries of the Northern Neck grant without having to pay the grantees.

The 1669 renewal of the grant declared that transfers of land made by the governor and his council in Jamestown prior to September 21, 1661 would remain valid. However, settlers and speculators with patents issued after that date were required to re-purchase their land, this time paying the grantees.5

Sir Thomas Culpeper saw an opportunity to increase the value of that grant. The other grantees were focused on more-immediate opportunities for gaining wealth in England, so he was able to acquire four of the five shares owned by others. Together with the 1/6th that he inherited, Sir Thomas Culpeper owned 5/6ths of the grant by 1681. His cousin Alexander Culpeper owned the last 1/6th, but acted as a silent partner while Sir Thomas Culpeper managed the grant.

Making a profit from the grant required selling land and collecting quitrents, which were the equivalent of modern annual property taxes. Land sales and quitrent collection could no be accomplished from England; a local agent in Virginia was essential.

The first Northern Neck land agent hired by Lord Culpeper was Thomas Kirton. He opened the initial land office in Northumberland County, and maintained it between 1670 to 1673. William Aretkin served between 1673-1677. Between 1677-1689, Daniel Parke and Nicholas Spencer were the agents, and they maintained the office in Westmoreland County. Philip Ludwell served as agent from 1690-1693. George Brent and William Fitzhugh moved the land office to Woodstock when they became agents in 1693.6

Buyers interested in land south of the Rappahannock River always went go to Jamestown (Williamsburg after 1699) to purchase land at the land office operated by the colonial government. After Lord Culpeper hired his first land agent, buyers interested in land between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers went to a separate Northern Neck land office that was located, logically enough, in the Northern Neck. The specific site of that land office changed as different people served as the agent. The last one (1762-1781) was west of the Blue Ridge near the Shenandoah River, but still within the boundaries of the grant.

future Fairfax Grant on John Smith's 1624 map

Source: Library of Congress, John Smith map

Lord Culpeper saw opportunity in Virginia that went beyond control of the Northern Neck. He decided to use his influence with Charles II to increase his wealth through land sales and collection of quitrents from the entire colony.

In 1673 he and Henry Bennett, the very influential Earl of Arlington, obtained another grant from King Charles II. The additional 1673 grant gave Culpeper and Arlington the right to sell the land and collect the quitrents from the rest of Virginia - outside of Culpeper's existing grant to the Northern Neck - for the next 31 years.

Under the terms of the new grant, the colonial government in Jamestown would remain responsible for administrative and judicial decisions as well as military defense, but all revenue based on Virginia land would flow to Culpeper and Arlington. The governor and General Assembly in the colonial capital would be limited to fees on shipping and taxes imposed on imports/exports, plus "poll" taxes imposed on all residents separate from their ownership of land.

The 1673 Culpeper/Arlington grant diverted the basic tax funding used to pay operating expenses, and to pay salaries of county officials and members of the House of Burgesses. Charles II was obviously more concerned about ensuring support from his nobles in England than in providing for effective government in Virginia.

Sir Thomas Culpeper worked hard to make a profit from his speculation in Virginia lands, but failed to sell much land. He also failed to collect many of the quitrents that landowners owed. Across the colony, Virginia landowners had not developed a strong tradition of paying the quitrents owed to the colonial government. Since Culpeper claimed the Northern Neck, the colonial government had no incentive for quitrents collection north of the Rappahannock River.

To replace the lost funding from quitrents and land sales, the General Assembly imposed new, excessively-high poll taxes. As a long-term strategy, the Virginia officials directed some of the extra funds to a plan to buy the Culpeper/Arlington grant. Many colonists complained strenuously about the high taxes, in part because some of the extra tax revenue was diverted to subsidize the lifestyle of the colonial officials rather than set aside to purchase the Culpeper/Arlington grant.

Culpeper finally negotiated a deal with the colonial government at Jamestown to accept a percentage of the quitrents that were theoretically owed to him, and also agreed to sell the 1673 grant to the colony. Once the king finalized the incorporation of Virginia and its purchase of the grant, the colonial government in Jamestown would be able to collect revenue again from land sales and quitrents - excluding the Northern Neck, which Culpeper still retained based on the 1649 grant.

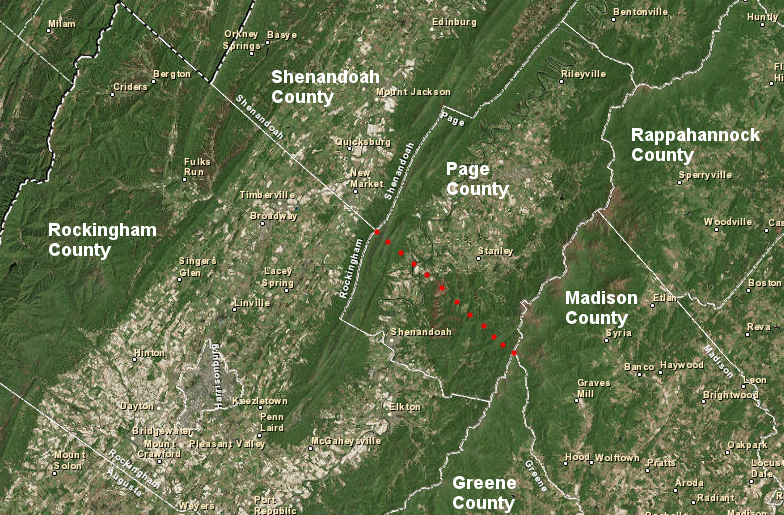

Fairfax Grant and modern political boundaries

The high taxes to purchase the Culpeper/Arlington grant helped trigger the 1676 uprising known as Bacon's Rebellion. News of the rebellion blocked royal approval of the plan to incorporate Virginia. That stopped the colony's purchase of the 1673 Culpeper/Arlington grant, and Culpeper failed in his effort to cash out some of his land claims in Virginia.

Culpeper then sought to enhance his capacity to collect revenue from his two grants. He used his influence again with Charles II and was appointed to replaced Sir William Berkeley as the next royal governor.

When Governor Berkeley was recalled in 1677 following Bacon's Rebellion, Sir Thomas Culpeper became the top appointed official for Virginia - but not in Virginia. Governor Culpeper broke the pattern followed by all previous governors. He initially chose to stay in England and appointed lieutenant governors to do the actual work across the Atlantic Ocean.

Governor Culpeper was finally forced by King Charles II to go physically to Virginia. After a brief Jamestown stay in 1680, Culpeper returned back to England. He must have considered Virginia to be a high-potential investment. In 1681, he acquired Arlington's share and became 100% owner of the 1673 proprietary grant, to accompany his 5/6ths share in the Northern Neck.

In 1682, King Charles II again ordered Governor Culpeper to sail back across the Atlantic Ocean and serve as governor in Jamestown. It was another short stay; Culpeper returned back to England in 1683. King Charles II then appointed a new governor for Virginia and Culpeper lost the salary of that position, but he did arrange to sell the 1673 grant back to the king.

In 1684, in exchange for surrendering the Culpeper/Arlington grant, Charles II granted Culpeper a 20-year pension. Thanks to the king's decision to purchase the 1673 grant from his own resources, Virginia taxpayers were no longer burdened by excessively-high taxes associated with the Culpeper/Arlington grant. After 1684, Lord Culpeper was no longer governor and no longer able to claim revenues from all of Virginia, but he still controlled the grant for all of the Northern Neck.7

Culpeper's agents for the Northern Neck managed to sell some parcels, including some that "escheated" to the proprietor of the grant. Those properties were based on grants previously awarded by colonial officials in Jamestown, but the claimants died or failed to complete the process of surveying and settling the land.

The agents sold just two large parcels during Culpeper's lifetime. One sale was for 5,000 acres before Culpeper was governor, and it included the future location of Mount Vernon in 1675.

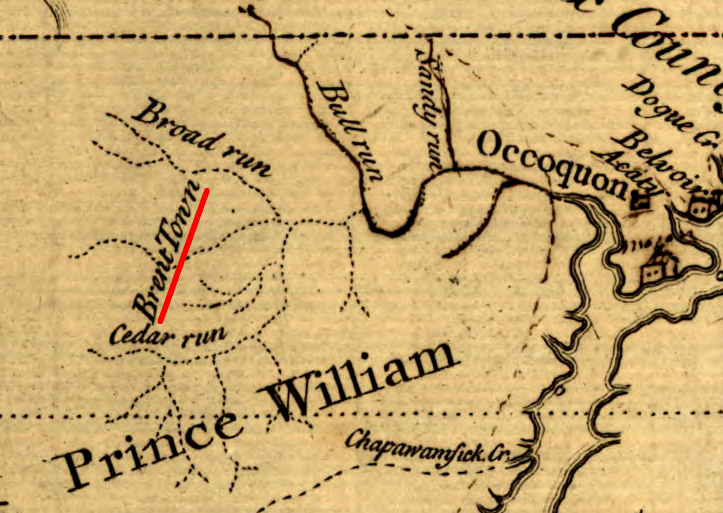

The other large sale was the 30,000 acre Brent Town parcel in Prince William/Fauquier counties in 1687. Three investors in England speculated they could convince French Huguenots to settle on that land, after French King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes that permitted religious freedom for Protestants. The three investors included a fourth partner living in Virginia, George Brent, to ensure local oversight and influence.8

Lord Culpeper managed to sell 30,000 acres to the four speculators investing in Brent Town

Source: Library of Congress, A survey of the northern neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the Rt. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the Bay of Chesapoyocke and between the rivers

Rappahannock and Potowmack:With the courses of the rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia, as surveyed according to order in the years 1736 & 1737

Land sales were rare, and collecting quitrents in the Northern Neck was even rarer. Culpeper had no representatives in Virginia with power equivalent to the sheriff in each county, the man who collected taxes for the colonial government and for the vestry. Despite the challenge of monetizing the Northern Neck grant, the potential value of the land remained clear.

Lord Culpeper knew the Northern Neck grant would expire in 1690, due to the 21-year deadline set in 1669. Tobacco farming was expanding and the population in the Virginia colony was increasing. Culpeper needed to find a way to hold onto his rights until the market materialized.

He got James II to renew the grant in 1688. The renewal modified terms and eliminated the deadline for settling the land in Virginia. That gave Lord Culpeper ownership of the Northern Neck in perpetuity, providing the time required until the colony expanded enough to increase the land value substantially.

The timing for grant renewal was excellent. Soon after approving it, King James II was expelled. He was replaced by William and Mary in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Had Culpeper waited, he may have lost all of his claims in Virginia.

The 1688 renewal also defined the grant boundaries. They extended westward specifically to the first heads or springs of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers, including:9

Sir Thomas Culpeper died in 1689. His widow Margaret Culpeper inherited his 5/6th's share, and she lived 30 more years without ever remarrying.

Lord Culpeper's only legitimate child, his daughter Catherine (Katherine) Culpeper, came from his marriage to Margaret Culpeper. He had two other daughters from a mistress with whom he lived openly, away from his wife. After his death, Margaret Culpeper contested the mistress's claims to valuable assets in England. Her legal and political efforts did not recover all of the property, but Margaret Culpeper retained her husband's claim to the Northern Neck grant.

The remaining 1/6th of that grant was owned by Alexander Culpeper, cousin of Sir Thomas Culpeper. At the end of his life, Alexander Culpeper was living in Leed's Castle. That was also the home of Margaret Culpeper after her husband, Sir Thomas Culpeper, had chosen to live elsewhere with his mistress. There Alexander Culpeper got to know the only daughter of Sir Thomas and Margaret Culpeper, Catherine Culpeper.

Alexander Culpeper died in 1694, and he had no children to inherit his estate. He left his 1/6th share in the Northern Neck grant to Catherine Culpeper. That bequest left Margaret Culpeper with ownership of 5/6th of the Northern Neck grant inherited from her husband, while daughter Catherine Culpeper owned 1/6th inherited from her father's cousin. Together, mother and daughter owned 100% of the grant.

Four years before Alexander Culpeper's death, the daughter Catherine Culpeper had married Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax of Cameron. The Culpeper and Fairfax families had been on opposite sides during much of the English Civil War. Culpepers were supporters of Charles I and Charles II, while the Third Lord Fairfax commanded armies fighting for the Parliamentary side in the 1640's. The Third Lord Fairfax ultimately switched to the Royalist side, and after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 many old rivalries were finessed.

Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax was the first (and only) individual to control 100% of the grant awarded by Charles II in 1649

Source: Library of Congress, Paintings. Lord Fairfax VI, Masonic Lodge, Alexandria II

Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax managed the 1/6th Northern Neck land claim of his wife together with the 5/6ths claim of his mother-in-law Margaret Culpeper. Like his late father-in-law Sir Thomas Culpeper, he anticipated future value. Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax refused to sell the family's proprietary claim when the colony made an offer in 1690. He blocked subsequent efforts of colonial officials to get the grant cancelled, and succeeded in having King William and Queen Mary reaffirm the valid status of the grant again in 1693. Fairfax protected through the renewal process a key part of the grant, requiring an annual payment in lieu of quitrents of just six pounds, thirteen shillings, and four pence.

Unlike Sir Thomas Culpeper, Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax never traveled to Virginia. He hired influential members of the gentry to serve as his land agents, including Philip Ludwell, George Brent, and William Fitzhugh. Starting in 1690, two years after James II had reaffirmed the grant, agents began selling land. All patents between the Rappahannock-Potomac rivers were recorded in special Northern Neck grant books, separate from other Land Office grant books used for the rest of the colony of Virginia.10

Robert Carter, hired as agent in 1702, effectively protected Fairfax's land claims against attempts by Williamsburg officials to limit the boundaries of the Northern Neck grant.

Because a key landowner in the Northern Neck, Richard Lee II, acknowledged the legitimacy of the Northern Neck grant, Carter had more success than earlier agents in generating revenue from quitrents and land sales. Carter was the first land agent to send a substantial income back to England.11

Robert Carter also patented so much land to himself and to family members that he became known as "King" Carter. Such land grants benefitted the Carter family more than the Fairfax family; Robert Carter was the richest man in Virginia and owned 300,000 acres at his death. Carter's children inherited large estates, thanks to the actions of the land agent living on the Northern Neck who supposedly was representing the interests of the Fairfax family far away in England.

Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax died in 1710. Margaret Culpeper, widow of Sir Thomas Culpeper and mother of Catherine Culpeper Fairfax, also died in 1710. The two portions of the grant, a 5/6th share and a 1/6th share, were inherited by two separate but closely-related people.

After Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax's death in 1710, Catherine Culpeper Fairfax was a widow. At that point, with no husband to control the family's land according to English law and custom, she finally gained control of the 1/6th share she had been given by Alexander Culpeper.

Margaret Culpeper did not give her 5/6th share to her daughter Catherine Culpeper Fairfax. Instead, Margaret Culpeper skipped a generation and she gave her land to a male heir. Her will transferred her 5/6th share of the Northern Virginia grant to her grandson Thomas Fairfax. He was the oldest son of Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax and Catherine Culpeper Fairfax, so she kept the land within the family. Practically, she also ensured her daughter would control the land grant.

Catherine Culpeper Fairfax's son Thomas Fairfax, who inherited that 5/6th share from his grandmother in 1710, had not reached the age of majority where he could act independently. He was only 16 years old when his grandmother Margaret Culpeper died, so his mother managed his financial assets. Even after he turned 21, he ignored the land grant. Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax would not get actively involved in managing the Northern Neck grant for another twenty years.

Catherine Culpeper Fairfax had not been satisfied with her husband's management of the family's wealth. She blamed her managers in Virginia for failing to generate adequate income from land sales and collection of quitrents. She replaced Robert Carter, the land agent her husband had chosen, and hired Carter's colonial rival Edmund Jenings as his replacement.

Jenings had been acting governor in the colony between 1706-1710, after Edward Nott died until Alexander Spotswood arrived. Jenings was in England on personal business when Catherine Culpeper Fairfax hired him. During his 1712-1722 tenure as land agent, Jenings had his nephew Thomas Lee do most of the actual work processing land grants and collecting quitrents.

Thomas Lee was the son of Richard Lee II, who had been the key Northern Neck landowner in acknowledging that the proprietary land grant was legitimate and enabling Robert Carter to serve as an effective land agent. Lee operated the land office at his home, Mount Pleasant, in Westmoreland County even after Jenings returned to Virginia in 1715 and began signing the final documents.

Catherine Culpeper Fairfax may have distrusted her son's ability to manage the family wealth, perhaps fearing that Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax would do no better than his father. When she died in 1719, Catherine Culpeper Fairfax's will gave her son just a life estate in her 5/6th interest. Owning a life estate allowed him to use the income from Northern Neck land sales and quitrents during his life, but limited his ability to mortgage or sell the entire grant.

After his mother died in 1719, Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax finally gained legal control over 100% of the Northern Neck grant. For the first time, one individual was responsible for 6/6ths of the grant; one person was the sole "Proprietor" of the Northern Neck.

Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax allowed the executor of his mother's estate to manage the grant for over a decade, and the executor rehired Robert Carter. Carter served a second term as the Northern Neck grant's land agent, starting around 1722, and moved the land office to his estate at Corotoman. From there, Robert Carter forced Edmund Jenings to make payments owed to the Fairfax family but which Jenings had not forwarded to England when serving as the proprietary's land agent. It appears Carter loaned Jenings the money needed for those payments, and eventually held mortgages and acquired control over a large percentage of the property owned by his rival.

Robert "King" Carter remained as land agent until his death in 1732. After Robert "King" Carter died and it was necessary to select a new land agent, Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax decided to take charge of his proprietary.

Robert "King" Carter around 1720

Source: Smithsonian Institution, James Monroe (by Chester Harding, 1829)

Lord Fairfax was stunned to read Carter's obituary and discover that his agent had become so wealthy. Perhaps as a result, Lord Fairfax came to Virginia in person to manage his asset there (unlike his father Thomas Fifth Lord Fairfax), and he never selected a Virginian to serve as his land agent. He chose instead a trusted family member, his cousin William Fairfax, to replace Robert "King" Carter.

William Fairfax had been living in Massachusetts, but in 1734 moved to Westmoreland County and then to Falmouth in Stafford County. He had been appointed to the position of Collector of Customs in Massachusetts, and assumed the same role for the Potomac River when he moved to Virginia. That provided him a reliable source of income, separate from whatever support he gained from serving as his cousin's land agent.

In Williamsburg, he was president of the Council. William Fairfax was a key member of the politically powerful, wealthy gentry that ruled the colony.

He built a mansion house, Belvoir, in 1741. It was located on a peninsula with a great view of the Potomac River, in Prince William County. In 1742, William Fairfax got the General Assembly to create Fairfax County. He served the new county as the presiding justice of the county court, and also as County Lieutenant.12

in 1741, constructing a brick home on the Potomac River demonstrated the wealth and influence of the owner

Source: Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland, An Ideal of "Old Belvoir Mansion" (p.90)

When Fairfax hired William Fairfax, he also responded to the latest colonial challenge to constrain his grant by filing the Fairfax v. Virginia suit in London. That suit ultimately determined ownership of the Northern Neck and the extent of the "proprietary" Fairfax Grant.

Throughout the colonial era, the Virginia government had consistently objected to the "proprietary" grant of the Northern Neck. Under terms of the various grants issued in 1649, 1669, and 1688, the colonial governor and General Assembly retained political and legal authority over the counties in the Northern Neck, but the grant owners (the "proprietors") had the authority to sell land and collect quitrents.

Around 1700, treasury rights replaced headrights as the primary vehicle for disposing of land "owned" by the colony. Sale of treasury rights, fees for processing individual land surveys and patents, and annual quitrents paid by owners of private land generated substantial revenue for the colony.

Once colonial settlement moved upstream of the Fall Line into the Piedmont, the dispute over the inland edge of the Northern Neck grant became an issue. Settlers seeking clear title had to know whether to file paperwork and pay fees to the colonial government in Williamsburg or the land office of the Fairfax family. If the colony could extinguish the Northern Neck grant somehow, revenues would flow to Williamsburg rather than to Leeds Castle.

On the Northern Neck, Lord Fairfax did not accept headrights or treasury rights issued by the Secretary of the colony in Williamsburg. Prices for proprietary land were not a significant issue. The colony sold treasury rights at a price of 10 shillings/100 acres. Lord Fairfax sold his land at 5 shillings/100 acres, for parcels 600 acres or smaller. For larger parcels which would take longer to settle and generate quitrents, he charged 10 shillings/100 acres.13

In the 1720's, the people in Williamsburg who supported Lord Fairfax's claim to the vast expanse of lands west of the Blue Ridge were primarily people associated with his payroll. The governors saw large land grants as a tool for rewarding allies on the Governor's Council, and for subsidizing population growth in areas where that was desired. The Virginia gentry saw land grants as a path to future personal wealth. As the colony's population expanded and soils in Tidewater were exhausted by tobacco, western lands would become more valuable.

The primary conflict involved the definition of the southern boundary of the grant (which stream was the Rappahannock River?), and responsibility for lands west of the Blue Ridge. One spur for Lord Fairfax to come to Virginia and fight for his claim was the colonial government's land grants in 1730-1732, when Governor Gooch authorized settlement on 385,000 acres across the mountains.

That included 40,000 acres sold to John and Isaac Van Meter and then 100,000 acres to Jost Hite (Joist Heydt) and Robert McKay. Those grants authorized them to take title to land near the Shenandoah River if they could attract enough settlers, with no payment to Lord Fairfax.14

Robert "King" Carter, as Northern Neck land agent, was willing to sell that land to whoever was willing to pay. However, purchasing land was the expensive option. Governor Gooch and his Council were willing to issue grants in the Shenandoah Valley, west of the Blue Ridge, without requiring payment. From their perspective, giving large amounts of land to people willing to recruit loyal-to-Virginia settlers was good public policy.

In Williamsburg, the colonial officials were anxious to attract new settlers to the far western frontier. They would serve as a buffer against anticipated attacks by Native Americans allied with French traders and officials based in Montreal/Quebec.

Lord Fairfax chose a playing field where he had the advantage over the General Assembly by filing the Fairfax v. Virginia suit in London. He recognized that the General Court in Williamsburg, composed of the governor and his appointed Council, would not rule in his favor. The General Assembly, dominated by burgesses elected from counties outside the Northern Neck, was also unlikely to support his claims.

The Fairfax v. Virginia suit asked the Privy Council in England to reaffirm the authority of the English king to issue the land grant now held by Lord Fairfax, and to establish the extent of the Northern Neck grant issued in 1688. The Virginians were forced to challenge the legitimacy of a grant that had been reaffirmed by William and Mary in 1693, and to seek an interpretation of the grant's wording that would limit the boundaries of the monarch's gift.

Lord Fairfax complained to officials in London that every grant authorized by Governor Gooch was illegal. Fairfax issued his own grants for some of the same parcels claimed by Hite, triggering the 1749 Hite v. Fairfax lawsuit in the Virginia courts that complicated land ownership for decades in the Winchester area.

Lord Fairfax came in person to Virginia in 1735 to defend his claim to the land and negotiate a survey of his boundaries with the General Assembly. He returned to England in 1737 to negotiate with the Privy Council, and then returned permanently to Virginia in 1747.

In 1649, 1688, 1693, or even 1735, no one had a clue about the exact location of the headsprings and thus the western boundary of the Fairfax Grant. John Lederer and others had explored west of the Blue Ridge starting in the 1670's, but lacked instruments to determine longitude. In 1716 Governor Spotswood thought Lake Erie was only a few days march away from the Blue Ridge. As noted by the US Supreme Court in 1910:15

Key to Fairfax acquiring such an expansive land grant was his success in getting the western limits defined as the headsprings rather than the heads of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers. The heads of the rivers were the limits of navigation. In 1608, John Smith determined the location of the heads of the two rivers. The places where rapids blocked his shallop from traveling further upstream, the heads of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers, later developed as Georgetown/Alexandria and Fredericksburg.

The sources of the rivers, the headsprings, were unknown in 1688 when Lord Culpeper renegotiated the language in the grant. By then it was clear that population growth would increase the value of land west of the Fall Line. Whether the Culpeper grant would extend west of the Piedmont region, and even the character of the land west of the Piedmont, was unknown. However, defining the western edge as the headsprings gave Lord Culpeper and later Lord Fairfax the opportunity to control the greatest acreage.16

Robert Carter, acting as the land agent in Virginia, had claimed in 1706 that the "first heads or springs" of the Rappahannock and Potomac river included all the area between the Rapidan and Potomac rivers.17

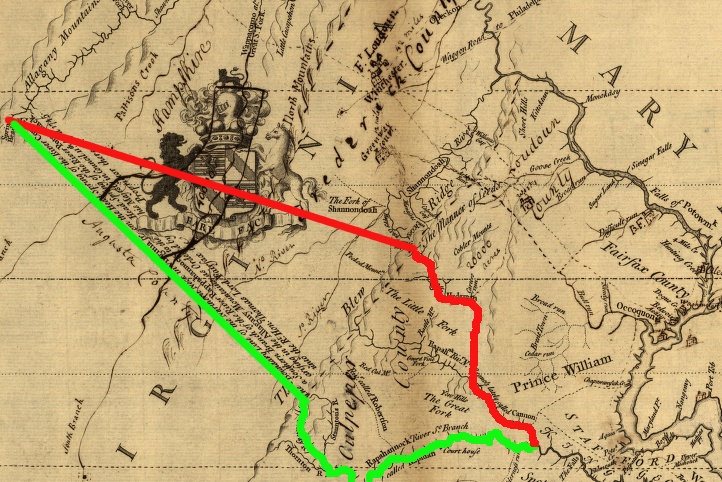

the Fairfax Grant could have been bordered on the south by the Rappahannock River, rather than the Rapidan River

Source: Fairfax County, 275th Anniversary of the Lord Fairfax Land Grant

Colonial officials in Virginia made several claims about the size of the Fairfax grant. One proposal limited it to the area between the confluence of the Shenandoah and the Potomac (Harpers Ferry today) and the falls of the Rappahannock (Fredericksburg today). Alternative options included defining the headwaters of the Rappahannock, not the Rapidan, as the southern headspring.

Fairfax's side noted that Governor Spotswood had changed the name of the south branch to Rapidan, from "southern fork" of the Rappahannock River. The colony argued that the headspring of the Rappahannock River was at Chester Gap and the headspring of the Potomac River was at Harpers Ferry, claiming:18

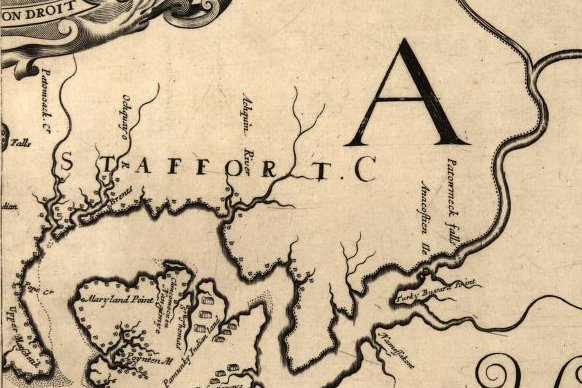

1670 map by Augustine Herrman, showing lack of understanding of area south of Potomac River and upstream of Fall Line - north is to the right

Patowmeck Fall = Great Falls

Turkey Buzzard Point = Fort McNair in DC

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670

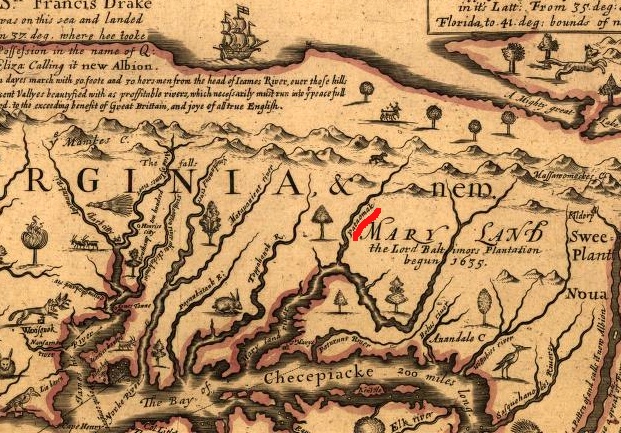

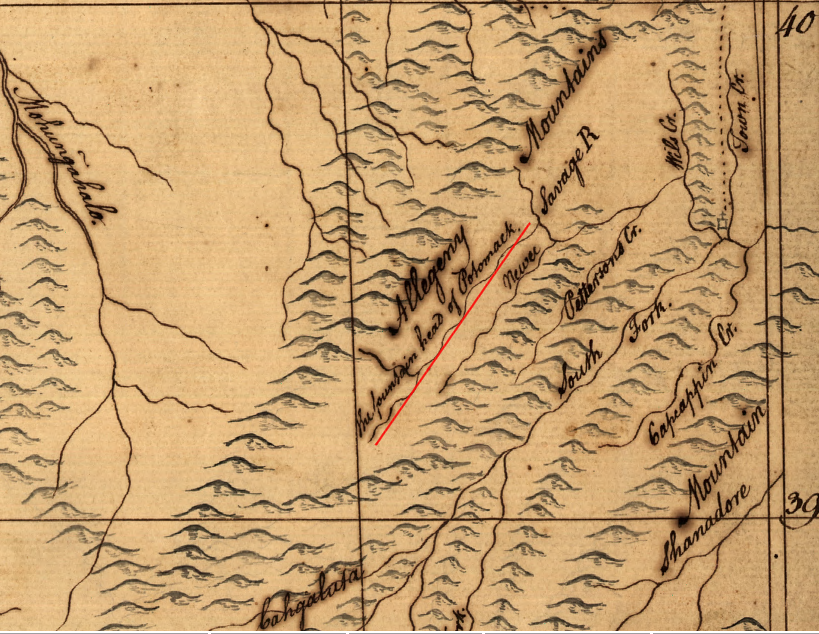

on John Ferrar's 1667 map, note confusion over western extent of Potomac Creek

(underlined in red) between Rappahannock/Potomac rivers - north is to the right

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it's latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England

In 1733, upon Fairfax's request, the Privy Council in London ordered that surveyors must go out on the ground and mark the grant boundaries.

In 1736, Governor Gooch and Lord Fairfax designated representatives to oversee the surveys of the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, so the lawsuit could be decided based on accurate maps. Fairfax chose Charles Carter, William Beverley and William Fairfax to serve as his representatives. Governor Gooch chose William Byrd II, John Robinson and John Grymes. Byrd was the uncle of William Beverley, but they represented opposing sides.

The six commissioners met at Fredericksburg and chose separate teams of surveyors. The teams were sent into the field to create maps of both rivers, while the surveyors stayed behind and communicated from a distance.

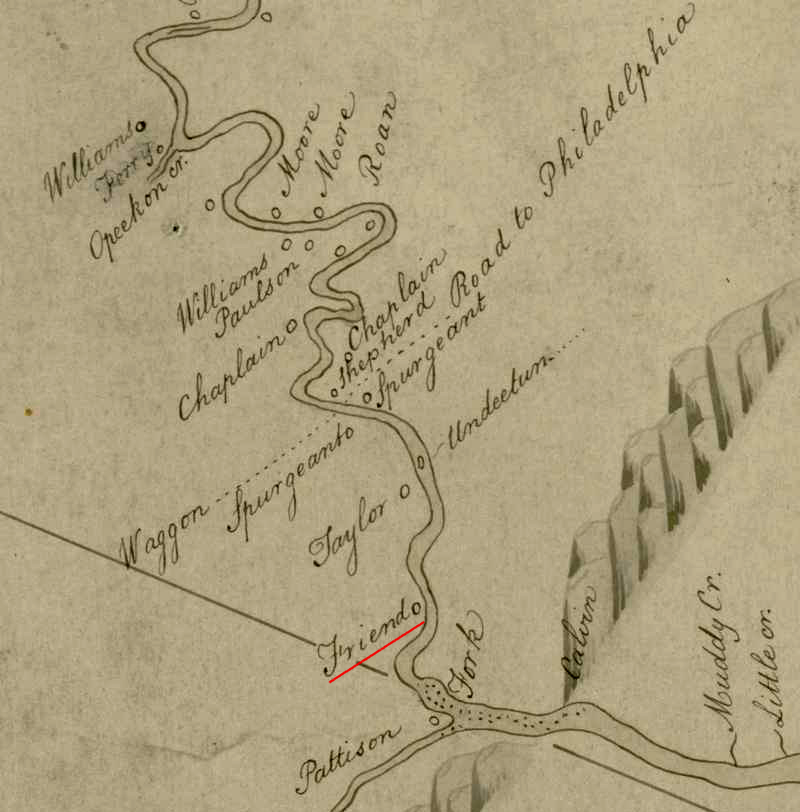

To map the Potomac River in 1736, Lord Fairfax's commissioners hired Benjamin Winslow and John Savage; Governor Gooch's commissioners hired William Mayo and Robert Brooke. The survey party started with 17 people, including chain carriers and the guide Thomas Ashby.19

Ashby was fired and replaced with Israel Friend after the surveyors reached the mouth of the Shenandoah River. That decision may also be associated with the switch from horses to canoes for the rest of the expedition. The surveyors worked steadily for over 200 more miles of documenting metes and bounds descriptions, going westward beyond the abandoned "Shawno old fields" and past any houses of colonists.

Peter Jefferson's 1747 map of the Fairfax Grant noted the location of Israel Friend's home at the mouth of the Shenandoah River

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the northern neck in Virginia (by Peter Jefferson, Robert Brooke, Benjamin Winslow, Thomas Lewis, 1747)

Upstream to the Fall Line, the boundaries of the Northern Neck were clearly defined by the main channels of the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. Further upstream, it became a tougher and tougher judgment call to decide at each confluence which stream should be called the Potomac River and which stream was a tributary. The stream with the most water was considered the main stem, and side streams were given other names such as Tonoloway Creek and Savage River.

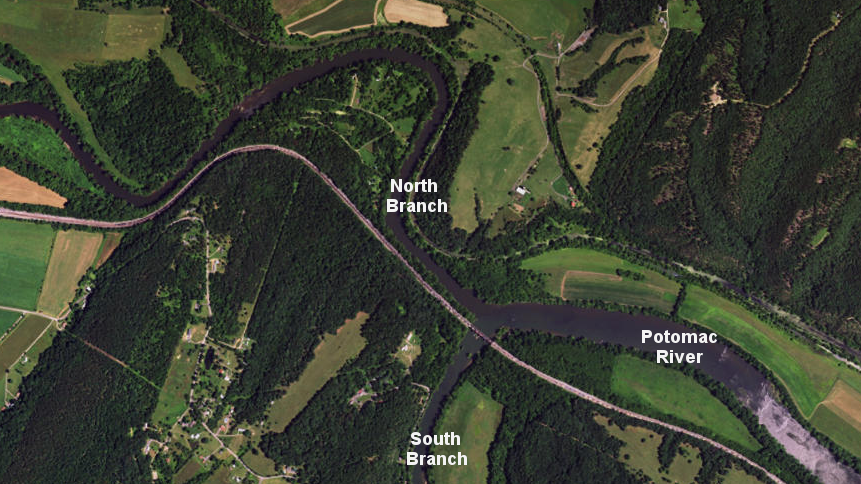

On November 13, the surveyors decided the North Branch of the Potomac River was the main stem. The channels of the South Branch and North Branch, where Thomas Cresap would later establish a trading site, are essentially the same size at their confluence. The South Branch enters at a sharper angle, and that may have been the key reason for choosing the North Branch. If the surveyors had chosen to continue up the South Branch, they would have discovered it extended further up into the mountains; western Maryland would have ended up much larger.

There were no Maryland representatives with the Virginia surveyors, even though the determination of the headspring would define the southwestern edge of that colony based on the 1632 charter to Lord Baltimore. The Virginians, whether allies of the colony or of Lord Fairfax, probably shared a common interest in marking that boundary far to the west in order to maximize the area reserved for Virginia and minimize the size of Maryland.

the surveyors mapping the northern edge of the Fairfax Grant chose the North Branch of the Potomac River to be the main stem on November 13, 1736, perhaps because the South Branch would have required making a sharp left turn as they moved upstream

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Winslow, Savage, Mayo, and Brooke mapped the path up the North Branch until they reached what was agreed to be the headspring of the Potomac River on December 14, 1736. There, they marked or "blazed" trees to identify the site. (The first Fairfax Stone was not marked there for another decade, when a second survey of the Fairfax Grant was completed.)20

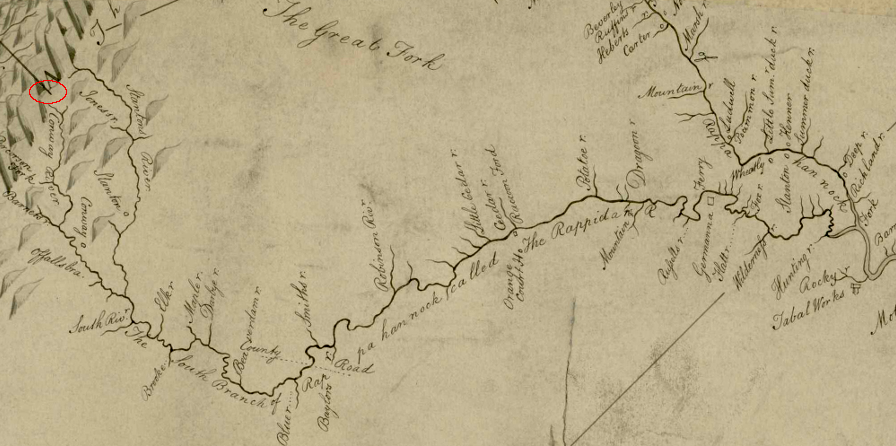

On the Rappahannock River in 1736, separate teams explored upstream from Fredericksburg to map the north and south forks. The colony hired John Graeme and George Hume to map the southern folk of the Rappahannock River, and James Wood to examine the northern branch. Lord Fairfax chose James Thomas to survey the southern branch, and James Thomas Jr. to survey the northern branch.21

where the north and south forks of the Rappahannock diverge (going upstream), the traveler must take a sharper angle to follow the north fork - though today that branch is known as the Rappahannock River, while the south fork has the separate name of Rapidan River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

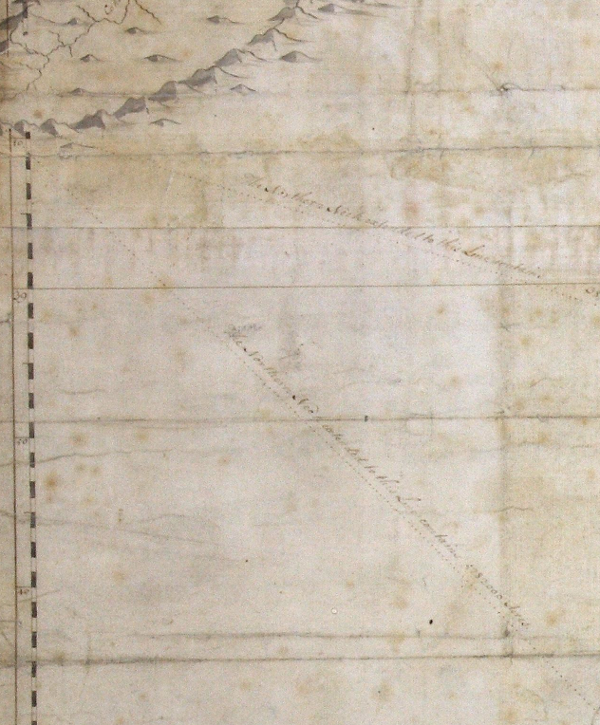

After the 1736 surveys were completed, William Mayo produced a consolidated map for the colony titled "A Map of the Northern Neck in Virginia, the Territory of Right Hon Thomas, Lord Fairfax situate between the Rivers Patomack and Rappahanock according to a late survey."

Mayo drew two "back lines" connecting the headspring of the Potomac River to a point on the Blue Ridge that could be considered the headspring of the Rappahannock River. One line connected the headwaters of the Conway River with the Potomac River, reflecting Lord Fairfax's claim to the most territory possible.

The other line was drawn further north, limiting the territory that might be included within the grant. That back line reflected the backup argument of colonial leaders.

The primary argument was that the Potomac River started at the confluence with the Shenandoah River, so Lord Fairfax's grant should not extend much distance past the Blue Ridge. If the Privy Council ruled the Potomac River headspring was further west, the backup argument was that the grant boundaries should follow the northern channel of the Rappahannock River at its confluence with the Rapidan River. That would place the Rappahannock's headspring at the start of the Hedgemans River.

West of the Blue Ridge, Mayo emphasized the colony's claim to the western lands by marking in the lower Shenandoah Valley:22

William Mayo's survey provided two options for drawing the back line from the headspring of the Potomac River, to either the head of the Hedgemans or Conway rivers

Source: Public Record Office (UK), A Map of the Northern Neck in Virginia, the Territory of Right Hon Thomas, Lord Fairfax situate between the Rivers Patomack and Rappahanock according to a late survey (William Mayo, 1737)

In response, Fairfax hired John Warner, who was surveyor in King George County, to produced a different consolidated map. It helped Lord Fairfax to win his case.23

alternative lines for boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, 1737 (Virginia proposed the red line, Fairfax proposed the green line including the land between Rappahannock-Rapidan rivers)

Source: Library of Congress, A survey of the northern neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the Rt. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the Bay of Chesapoyocke and between the rivers

Rappahannock and Potowmack:With the courses of the rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia, as surveyed according to order in the years 1736 & 1737

In 1745, the Privy Council in London decided in favor of Lord Fairfax, designating the spring at the head of the Conway River as the basis for the southern boundary of the grant. The London officials declared on April 11, 1745 that:24

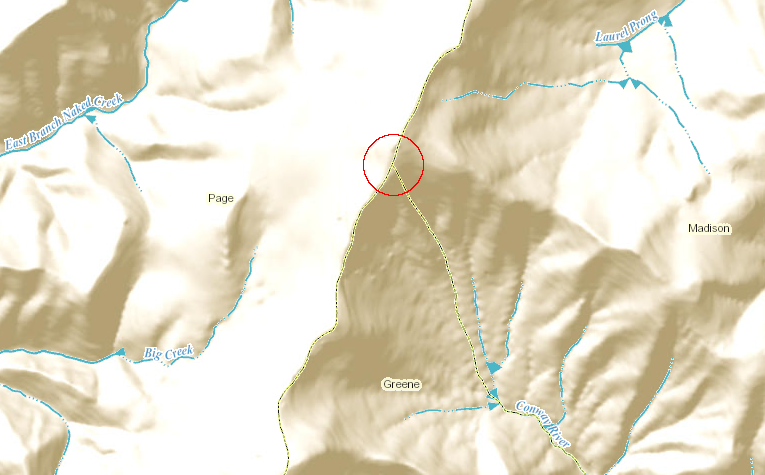

in 1745 the Privy Council decided that the Rapidan River was the southern fork of the Rappahannock River, and the headspring of the Conway River (red circle) would define the southern boundary of the Fairfax Grant

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the northern neck in Virginia (by Peter Jefferson, Robert Brooke, Benjamin Winslow, Thomas Lewis, 1747)

Defining the "straight line North West" from the Conway River to the "place in the Allagany Mountains where that part of the River Pattawomeck... arises" required yet another survey.

From September-November, 1746 a 75-mile long "back line" was surveyed between that point and the start of the Rappahannock River. Four surveyors were hired. Peter Jefferson and Robert Brooke III (whose father Robert Brooke II had been on the 1736 survey) represented Virginia, while Lord Fairfax hired Benjamin Winslow and Thomas Lewis.

The surveyors completed an initial trial line between the Conway and Potomac, where they marked initials on numerous trees at the headwaters of the Potomac River (plus FX on one stone...). Once they reached the end of that traverse, they adjusted their bearings, started again from the starting point of the Potomac River, and surveyed back.

The actual Fairfax Line was defined on the return trip to the starting point of the Rappahannock River on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge. The return journey was slightly over 75 miles, There were diversions around obstacles and side trips required to connect to the trial line surveyed on the initial trip, so the surveyors walked about 200 miles during nearly three months in the field.

survey of "back line" to and from Fairfax Stone from headspring of the Rappahannock, 1746

Source: The Fairfax Line: Thomas Lewis's Journal of 1746, (image from Wikipedia, Fairfax Line)

The 1746 survey started at the headspring of the Conway River on the east side of the Blue Ridge. As determined by the Privy Council, the starting point of the southern branch of the Rappahannock River (known as the Rapidan River) defined the point of beginning for the Rappahannock River, and the edge of the Fairfax Grant.

Finding that starting point at the end of the summer of 1746, ten years after the headspring was first identified, would have been a challenge. Trees blazed in the 1736 survey would have been a valuable guide for deciding exactly where to start, if the springs were dry as normal in September.

the backline of the Fairfax Grant defines the southern boundary of Shenandoah County, but not Page County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

"Gentleman commissioners" accompanied the hard-working surveyors again to ensure the interests of the colony and Lord Fairfax were fully represented. The commissioners made the decision on which spring in the headwaters of the Conway River was the "headspring." Afterwards, it appears the surveyors were able to make decisions without appealing to those commissioners, unlike the experience in 1728 when the dividing line separating Virginia-Carolina was surveyed. In that survey, William Byrd II and his fellow commissioners made key decisions regarding where to end one line and start another, especially at the confluence of the Blackwater/Nottoway rivers.25

Surveying was hard work in 1746. "Chain men" stretched iron chains with a fixed number of links between poles to measure distance, 66' at a stretch. Surveyors determined bearings with a compass, and at least one was broken during the expedition. The line-of-sight technology required cutting a straight line through brush, swamps, and virgin forests to sight the poles, so whatever hills and valleys were on the way had to be crossed rater than bypassed.

The topography was challenging at the start in the Blue Ridge and then crossing Massanutten Mountain. The Devil's Backbone brewery is named after a spot on the survey line where the terrain was so rough, several horses were killed.

The surveyors followed straight lines despite the difficulties of crossing stream valleys and climbing steep cliffs, but commissioners took the baggage on an easier path when necessary. On September 25th, the first day of surveying northwest from "a Red oak and 5 Cotton trees" at the head of the Conway River up across the Blue Ridge:26

the Devils Backbone beer is named in honor of the challenges overcome by surveyors marking the Fairfax "back line" in 1746

Source: Devils Backbone Brewing Company

After surveying for 35 days, the expedition reached the "headspring" of the North Branch of the Potomac River. That site had been marked in 1736 by blazing initials and symbols on nearby trees. The 1746 survey team marked "bearing" trees again, but also chiseled FX in a rock to create the first Fairfax Stone.

One of the surveyors hired by the colony of Virginia in 1736 for the examination of the southern folk of the Rappahannock River may have made his own marks there in 1743. George Hume surveyed the boundary between Frederick and Augusta County that year, documenting a boundary line from the headspring of the Hedgemans River to the headspring of the Potomac River.27

The initial line from the Conway River was off roughly 4 miles; bearings and distances were not accurate on the original trip northwest from the Blue Ridge. After making appropriate adjustments for a return bearing, the return survey to the southwest required only 24 days. Chainmen and surveyors pulled 80 chains, each with 100 links, to define one mile of distance.

The final "official" line defined on that return trip ended on November 13, 1746 with just a 100-yard error away from the original point of beginning. The survey was honest and accurate; neither colony nor Lord Fairfax benefitted from any questionable interpretations of where to draw the back line.28

Surveyors repeated at the headspring of the Conway River what they had done to mark the spot at the headspring of the Potomac River. Another stone was marked with the initials FX, and trees blazed to help future surveyors and property owners identify the location.

the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers easily defined the Northern Neck peninsula at their mouths, but determining locations of headsprings all the way upstream was a judgment call - made in London in 1745 by Privy Council members who had never been to Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

By winning the argument over the western and southern boundaries of his grant, Lord Fairfax obtained title to 5.2 million acres. Had Virginia officials managed to get their boundary proposal approved by the Privy Council, his grant would have been limited to 1.5 million acres.29

In 1999, over 250 years after the back line survey, a Surveyors Historical Society Rendezvous attempted to locate the Fairfax Stone on the Conway River. The best candidate, with what may have retained a faint impression of an F, was excavated by archeologists in 2000. There was no obvious evidence to prove it was set in the ground by the surveyors in 1746.30

In 1747, after winning his case in the Privy Council, Thomas, Sixth Lord Fairfax returned to Virginia permanently in 1747, after winning his case in the Privy Council. Between 1747-1751, he lived with William Fairfax at Belvoir (now the site of Fort Belvoir). There he encountered William Fairfax's neighbor, George Washington, and hired him as a surveyor. Within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, Lord Fairfax could set his own standards, and George Washington was not required to get a license or pay fees to the college at William and Mary.

Lord Fairfax arranged for his nephew Thomas Bryan Martin to join him in Virginia and assist his cousin William Fairfax in his operations as the land agent for selling parcels within the grant. Fairfax and Martin moved west across the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah Valley in 1751, settling west of Ashby's Gap where modern Route 50 crosses the mountains. In 1752, when Martin turned 21 years old, Lord Fairfax gave him 8,840 acres. When William Fairfax died in 1757, Thomas Bryan Martin became Lord Fairfax's last land agent.

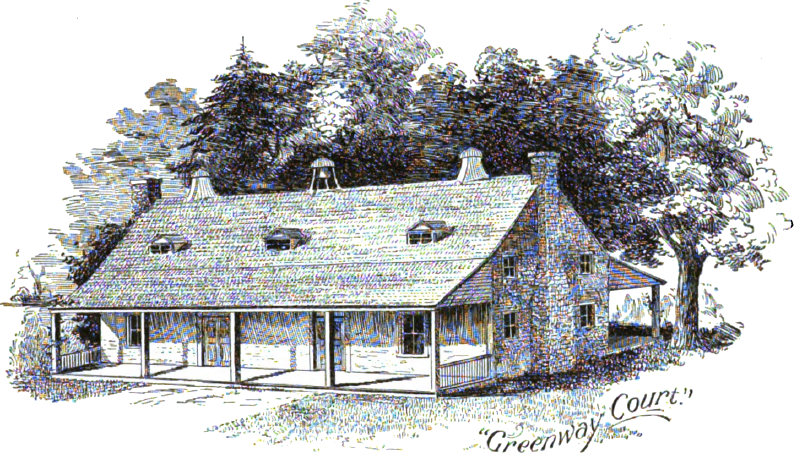

The two men, from very different backgrounds, lived in simple quarters in what was then Fauquier County (now Clarke County). They occupied a one-and-a-half-story stone house which had been intended for a caretaker. Fairfax named his small stone house in the Shenandoah Valley "Greenway Court," and settled there permanently in 1762. Plans for a larger manor house, suitable to Lord Fairfax's status, were never implemented.

The last Northern Neck grant land office for issuing deeds and collecting quitrents was built at Greenway Court in 1762.31

Local residents claim the 11-foot high white post in the road near to the land office was planted by George Washington around 1750 to guide people to the land office. The wooden post has been repaired and replaced multiple times; Mount Vernon reportedly supplies new wood from locust trees when needed. After one vehicle ran into it, a new police officer asked who had placed the post in the middle of the road. The man responsible for making repairs responded that it was George Washington, after which:32

Lord Fairfax lived a simple life at Greenway Court in the steward's house, and never built a grand main house there

Source: Magazine Of American History, Greenway Court (September 1893, p.137)

the appearance of Greenway Court is interpreted by artists in different ways, but Lord Fairfax clearly chose to live in a simple structure that did not manifest his wealth - unlike Belvoir or Mount Vernon

Source: Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland, Greenway Court (p.103)

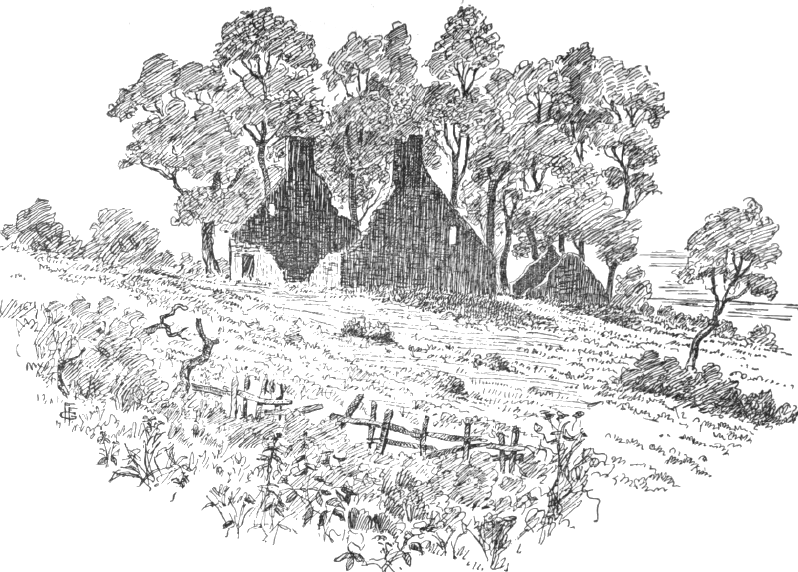

the roof of Lord Fairfax's home at Greenway Court collapsed in 1834, and the house was then torn down

Source: Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland, The End of Greenway Court (p.105)

At the time, the Shenandoah Valley was the western edge of colonial settlement. The 1744 Treaty of Lancaster had officially displaced the Iroquois from their traditional hunting grounds, but the treaty still permitted the Iroquois to travel on the "Great Road" to trade/fight with the Cherokee and Catawba in North Carolina. In the first part of the French and Indian War, from 1754 until Fort Duquesne was captured by the English in 1758, cabins in the valley were raided by Shawnee and settlers killed.

Lord Fairfax chose to live far away from the settled Tidewater and the sophisticated gentry, the social class that came closest to the society in which he grew up in England. Though his reasons will never be known for sure, there is some evidence that he was rejected by a woman he intended to marry before he came to Virginia in 1735; Lord Fairfax was a life-long bachelor.

Lord Fairfax stayed neutral during the Revolutionary War, but paid double taxes because he refused to declare allegiance to the rebellious state of Virginia. State officials did not harass him, even though he was a peer of the realm and Virginia was at war with KIng George III. George Washington apparently indicated that Lord Fairfax should just be ignored. When Virginia abolished quit rents in 1779, it allowed Lord Fairfax to continue to collect the two shillings per year from lands within his grant boundaries.

He died in 1781, soon after learning of Cornwallis' defeat at Yorktown, and was buried in Winchester. Robert, 7th Lord Fairfax and younger brother of Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax, inherited the title of Lord Fairfax and his mother's right to 5/6ths of the proprietary land grant in Virginia. However, Virginia seized all loyalist property in 1779. Robert, 7th Lord Fairfax accepted a loyalist compensation payment from the Parliament and dropped his claim to Virginia land.

Thomas, the 6th Lord Fairfax, willed the house and 1.000 acres to his nephew, Thomas Bryan Martin. Lord Fairfax had used Thomas Bryan Martin as his land agent since 1751, replacing his cousin William Fairfax. Fairfax gave the rest of his 1/6th inherited land grant to the brother of Thomas Bryan Martin, Denny Martin.

The small house at Greenway Court was finally torn down after the roof collapsed in 1834. There are no ruins visible today of his house or of the nearby log cabins once occupied by the people he owned as enslaved workers. The more substantial structure used for the land office, made from limestone blocks, still remains.

Denny Martin renamed himself as Denny Fairfax, as required in Lord Fairfax's will to qualify for inheriting the land. However, Virginia had seized the unsold land within the grant in 1779 during the American Revolution, along with other loyalist property across the state. Denny Fairfax inherited unclear title.

Virginia's confiscation of the Fairfax Grant was not completed before the Treaty of Paris (1783) and the Jay Treaty (ratified in 1795) protected property rights of British loyalists during the Revolutionary War. Denny Fairfax claimed that the Federal treaties were the law of the land and that Virginia's confiscation was not legitimate; technically, he still had a 1/6th claim to the entire grant.

When Robert, 7th Lord Fairfax died in 1793, his will transferred most assets to his brother-in-law Denny Martin. The will included a requirement that Martin change his last name to Fairfax, so Denny Martin became Denny Fairfax. The title of Lord Fairfax transferred to a different person, Lord Fairfax's cousin Rev. Bryan Fairfax. Rev. Bryan Fairfax was a son of William Fairfax of Belvoir and a close friend of George Washington, and he became 8th Lord Fairfax.33

After Denny Martin/Fairfax died, his brother and then his two sisters inherited his claim to the Fairfax Grant. Robert, 7th Lord Fairfax was compensated by Parliament in 1792 for the lands seized by Virginia, in a bill in which claims of other loyalists were resolved.

According to Denny Martin's heirs, the claim to the Fairfax Grant's unsold land had not been extinguished by the 1779 Virginia confiscation. After Thomas, Sixth Lord Fairfax died in 1781, there were 35 years of negotiations and lawsuits regarding ownership of the portions of his grant which had not already been sold. Legal title was resolved finally through the Martin v. Hunter's Lessee case.

In 1789 David Hunter purchased 788 acres of land from the Commonwealth of Virginiaa. The state claimed it had acquired the property based on the 1779 confiscation. Denny Fairfax sued, asserting he still retained ownership based on the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Part of that peace deal to end the American Revolution was a promise to restore property seized from loyalists.

The Virginia Supreme Court ruled against Denny Fairfax. The state court decided that Federal treaties could not supersede state law and Virginia courts could make their own interpretation of the 1783 treaty. According to the Virginia Supreme Court, the state was allowed to confiscate the unsold lands in the Fairfax Grant under the 1779 state law.

John Marshall gambled that he could overturn the state court decision in a Federal court. He acquired the right to buy 160,000 acres that Denny Fairfac claimed he owned, despite Virginia's attempted confiscation.

Marshall and others borrowed money to finance a series of lawsuits. Their case was speculative; if Marshall could not convince Federal courts to assert the right to overrule a state court and give Denny Fairfax ownership, then Marshall and his fellow investors would receive nothing. Denny Fairfax and his heirs would not get paid for "Fairfax" land unless a Federal court decided that the 1779 confiscation was not legitimate, and the states would accept that Federal courts had the authority to make that ruling.

In the subsequent Martin v. Hunter's Lessee case in 1816, the US Supreme Court declared that the Virginia court ruling was not the final word. The Federal court ruled that it had authority over state courts to interpret federal law.

The US Supreme Court decision gave the Commonwealth of Virginia clear title to the Fairfax Grant lands that had not already been sold before 1779. Settlers who had purchased lands directly from Fairfax, or had title that dated to colonial patents issued prior to the Fairfax Grant on September 21, 1661, got clear title to their lands.

In the end, when the case ended up at the US Supreme Court, Marshall was Chief Justice and had to recuse himself.34

The 1746 survey resolved the southern and western location of the grant boundaries within Virginia. Other disputes regarding land ownership within the grant and the northwestern corner of the boundary still kept the courts busy for 150 more years.

The Hite vs. Fairfax lawsuit continued until 1786, ultimately being decided in favor of Hite's claims. Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax initially lost to Hite in Virginia courts, but the English lord appealed to the Privy Council in 1771. The London officials were slow to respond, however.

After the American Revolution, officials in London had minimal influence on Virginia land policy. The Virginia courts finally resolved Hite vs. Fairfax in Hite's favor. Settlers who had purchased land west of the Blue Ridge prior to 1738 from the colonial government, rather than Lord Fairfax, had clear title to their land.

All land not sold by Lord Fairfax before his death was transferred to the Commonwealth of Virginia, except for 140,000 acres which remained entangled in lawsuits until 1816. John Marshall used his legal skills to argue that the state's seizure of Lord Fairfax's land was not legal, and that

35

Thomas Kemp Cartmell, Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants: A History of Frederick County, Virginia (illustrated) from Its Formation in 1738 to 1908, Eddy Press Corporation, 1909, p.518, https://books.google.com/books?id=sdFczYzblKQC (last checked April 5, 2018)

location of headspring of the Rappahannock River - at the headwaters of the Conway River, as depicted on Fry-Jefferson Map of 1755 (after 1746 survey defined boundaries of the Fairfax Grant)

Source: Library of Congress, Fry-Jefferson Map

by the start of the French and Indian War, the North Branch of the Potomac was accepted as the headwaters

Source: Library of Congress, A trader's map of the Ohio country before 1753

The exact location of the headspring of the Potomac River became a matter of dispute in 1852. Maryland claimed:36

U.S. Supreme Court, Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 1 (1910), page 217, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/217/1/case.html (last checked January 4, 2015)

However, in 1859, a United States Topographical Engineers survey by Lieutenant Michler reported:37

U.S. Supreme Court, Maryland v. West Virginia, 225 U.S. 1 (1912), http://supreme.justia.com/us/225/1/case.html (last checked August 9, 2009)

By 1884, vandals had destroyed the original Fairfax Stone. The Davis Coke and Coal Company installed a replacement. By 1911, that replacement was gone, and only the base of a 4-foot high survey marker built by Lieutenant Michler in 1859 still survived. In 1910, a replacement concrete marker was erected, and in 1957 the West Virginia Conservation Commission placed a 6-ton sandstone marker at the site.38

Nomination of Fairfax Stone to the National Register of Historic Places, http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/grant/70000653.pdf (last checked August 9, 2009)

Modern location of the long-vanished original Fairfax Stone

As a result of a lawsuit between Maryland and West Virginia, the US Supreme Court redefined the western boundary of Maryland in 1912. The southwestern corner of Maryland was defined as a point about a mile north of the Fairfax Stone, where the Potomac River curves around to intersect again the straight line going north from the stone. The modern six-ton sandstone marker (the fifth Fairfax Stone) is completely within West Virginia, now in a West Virginia state park, and the Fairfax Stone no longer borders Maryland.39 U.S. Supreme Court, Maryland v. West Virginia, 225 U.S. 1 (1912) http://supreme.justia.com/us/225/1/case.html (last checked August 9, 2009)

Today's boundary between Shenandoah and Rockingham counties follows that 1746 back line that connected the headwaters of the Rapidan to the headwaters of the North Branch of the Potomac River. That line crosses Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park between the Hazeltop overlook and Lewis Mountain campground. East of Skyline Drive, the Fairfax Line stops at the headwaters of the Conway River where Greene, Madison, and Page counties meet. Greene County, Orange County, and Spotsylvania County have boundaries defined so they are south of the Rapidan River and outside the Fairfax Grant.

the headspring of the Rapidan River is east of the modern Hazeltop Ridge Overlook on Skyline Drive

Source: US Geological Survey, The National Map

Lord Fairfax died at Greenway Court, located in Frederick County at the time (now in Clarke County)

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Greenway Court, the seat of Lord Fairfax (p.235)

the boundaries of Page, Madison, and Greene counties are defined in part by the location of the headspring of the Rappahannock River, flowing initially off Hazeltop Mountain into the Conway River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

if the Fairfax Grant of 90 square miles had been located in Central Virginia...

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online