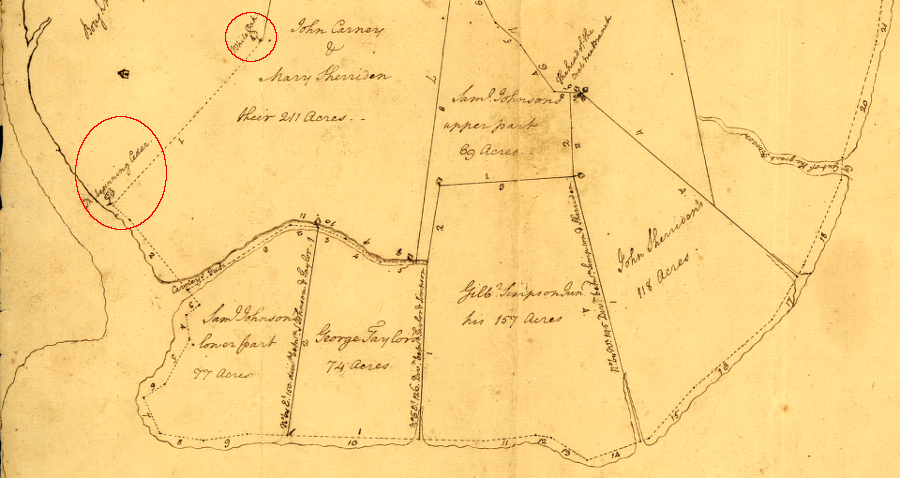

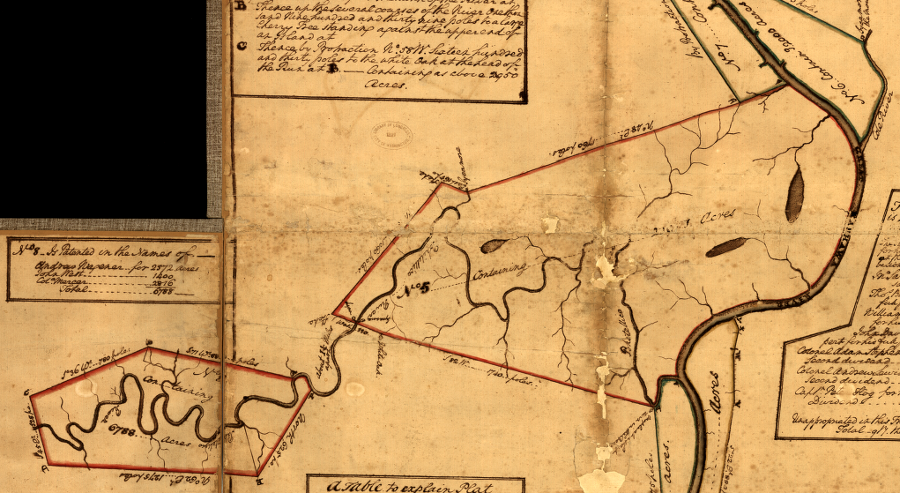

simple rectangular metes and bounds survey in Shenandoah Valley, 1750

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington survey - Plat of survey for John Lindsey of 223 acres in Frederick County, VA

simple rectangular metes and bounds survey in Shenandoah Valley, 1750

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington survey - Plat of survey for John Lindsey of 223 acres in Frederick County, VA

From colonial times, individual Virginia properties were surveyed according to the metes and bounds system. Chains and compasses were used to mark lines from a starting point, typically a natural feature such as a large white oak tree.

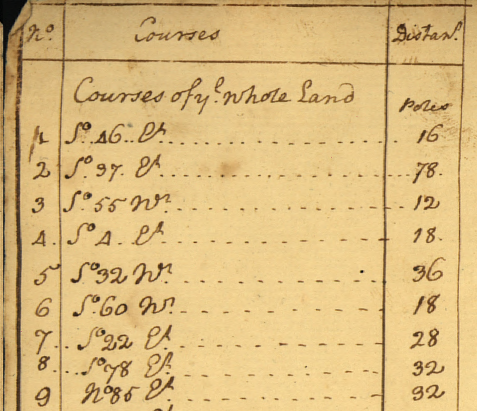

Surveying in Virginia was not based on the metric system. The units were traditional English measures, with land measured by the acre (43,560 square feet). A Gunter chain was 66 feet long, and each of the 100 iron links in that chain was 66/100 of a foot (7.92 inches) in length. A chain stretched to its length 80 times would define the length of a mile. A chain stretched out 10 times in one direction (600 feet) and once in the other direction (66 feet) would define a rectangle enclosing one acre.

Other than town lots in places such as Williamsburg and Alexandria, Virginia landowners rarely purchased property defined by rectangles. Instead, surveyors were directed by land purchasers to define polygons that enclosed high-quality land for farming and excluded areas with poor soil. Lord Fairfax tried to require surveys to have rectangular or trapezoidal lot lines, but even those parcels were located at odd angles to each other in order to incorporate the best land. As a result, slivers of the less-attractive land ended up as gaps or "gores" between surveyed parcels.

Surveyors would move away from a recognizable starting point, using a compass to determine the direction in which they were moving. Assistants would cut a straight line through the woods and stretch a chain of a known length along that line, following the bearing determined by the surveyor.

The chain would be stretched the full length, then the poles moved to stretch the chain forward again until reaching the end of the line in that one direction. The surveyor would use the compass to determine the change in angle to define the next bearing, and the chain would be pulled in that new direction the appropriate distance. This process would be repeated until returning to the point of beginning, with trees marked at each change in direction to define the boundary.

modern surveyors use metal tapes - and electronic distance measuring technology - rather than chains with links to measure distance

Source: Colorado Department of Transportation, Basic Surveying

To improve accuracy, surveyors were trained to "backsight" from the forward end of the chain to verify the bearing was consistent. If in a hurry, or if interested in enclosing "surplus" acreage beyond what was authorized, surveyors could speed up their field work at the price of accuracy.

Compasses were instruments based on magnets, and some were more accurate than others. Part of the surveyor's skill was knowing how to adjust compasses, based on star and sun sightings, to determine magnetic north at each location.

Pulling the chain involved travel through rough country under difficult conditions, and a half-chain only 33' long was commonly used in Virginia. Streams, swamps, cliffs, and other obstructions were challenges for chainmen pulling poles 66' forward to maintain a straight line. If the bearing determined by the surveyor required travel on a physically difficult path, then the line might veer slightly. At other times, an offset line might be surveyed to avoid a major obstacle, with the "straight" line between two points calculated later.1

The surveyor would write down the bearings and distances in a notebook while in the field. Back in their office, surveyors would produce a sketch to illustrate the polygon of land defined by the survey.

The official county surveyor would approve the document, and the survey would be filed at the Public Records Office in Jamestown/Williamsburg or in the county courthouse. When associated with a grant or "warrant," the survey was an essential part of the land deed that documented legal claim to ownership of defined parcels of land.

hauling a chain and moving pins was hard physical labor in colonial Virginia

Source: Bureau of Land Management, Surveys and Surveyors of the Public Domain, 1785-1975, George Washington as a surveyor (p.6)

Land could be acquired through headrights. For every person ("head") imported to Virginia, the colonial government would authorize 50 acres of land. The person who paid the transportation costs to import indentured servants earned the 50 acres. Sometimes influential ship captains conspired with colonial officials to get headrights for sailors who technically were imported to Virginia, but then sailed away on the return trip rather than added to the colony's permanent labor force.

The colonial government also sold Treasury rights, so people with enough cash could purchase land without having to acquire a headright. A headright claim could be sold to others before it was converted into a specific parcel of land through a standard process:2

The governor and his Council also made direct grants of land to members of the gentry, and to individuals that could attract settlers to occupy whatever tracts of land were granted. On June 17, 1730, the Council gave 10,000 acres to John Van Meter of the Province of West Jersey, who reported that "he & divers other German Families" desired to settle west of the Blue Ridge along the Shenandoah River and Opequon Creek.

Robert Carter, who was the land agent for Lord Fairfax, objected at the meeting to the proposed Van Meter grant. Carter asserted that it was outside the authority of colonial officials in Williamsburg to give away lands that were owned by Lord Fairfax, but the Council simply recorded his comments before acting.

The Council made numerous other grants that day as well, and its journal documents:3

in 1760, George Washington copied a survey when he purchased River Farm at Little Hunting Creek from William Clifton, with bearings and distances marked from "the beginning cedar" to the "white oak" and other points

Source: Library of Congress, A plan of Mr. Clifton's neck land platted by a scale of 50 poles to the inch

the William Clifton survey marked distances in "poles" (each pole was 16.5 feet)

Source: Library of Congress, A plan of Mr. Clifton's neck land platted by a scale of 50 poles to the inch

Typically the initial survey to define a parcel in colonial Virginia involved selecting the best-quality land along a river, where soil was deepest and most suitable for farming. The surveyor would define parcel boundaries to exclude slopes of hills, so the boundaries created polygons with straight lines going at different angles. Later arrivals would have to carve their parcels from the lower-quality hillsides.

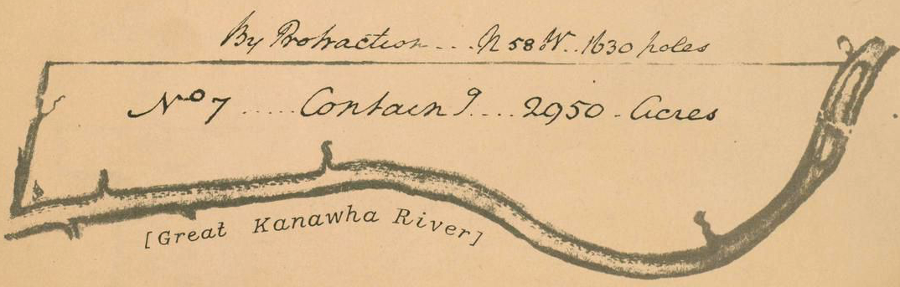

the surveyor aligned parcel boundaries to include lands that would be most profitable for farming, while still minimizing the number of angles in the survey

Source: Library of Congress, Eight survey tracts along the Kanawha River, W.Va. showing land granted to George Washington and others

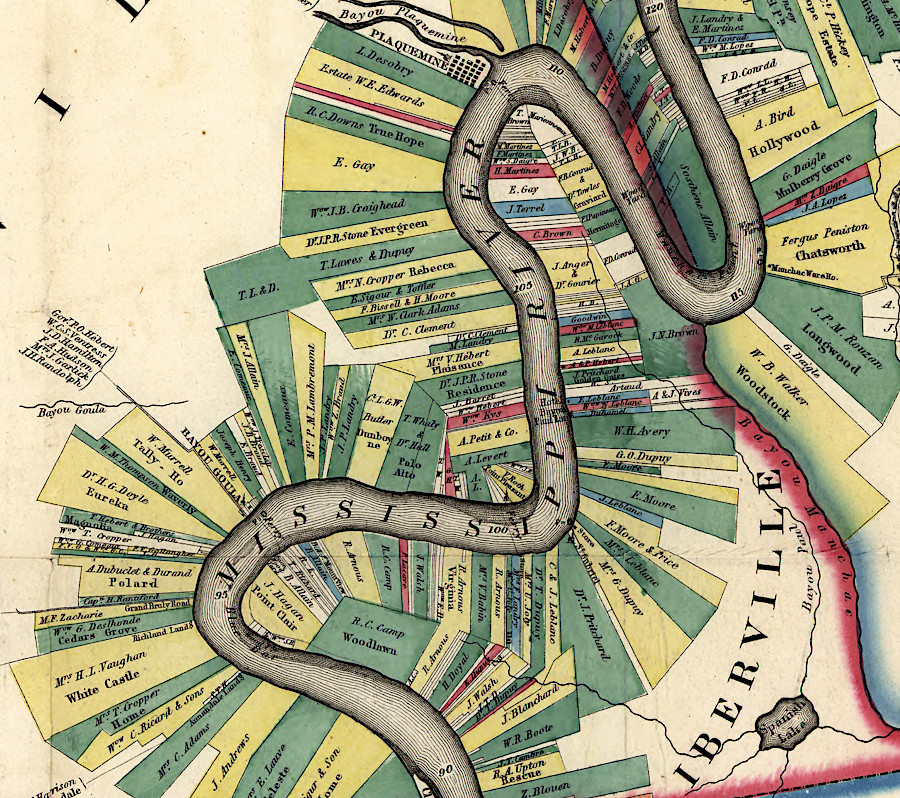

The French established a different survey pattern for their land claims in Canada, Louisiana, and the portion of New France which ended up after 1783 as the Northwest Territory of the United States. They defined parcels that were long, narrow strips of land starting at the river, then stretching across the high-quality bottomlands and including some forested land on the hillside.

Long lots were surveyed with boundaries designed to maximize the number of settlers with waterfront access, while incorporating fertile bottomlands and less-desirable river bluffs in each parcel. That approach was more equitable, allowing everyone to get access to shipping on the river and a portion of good farmland.

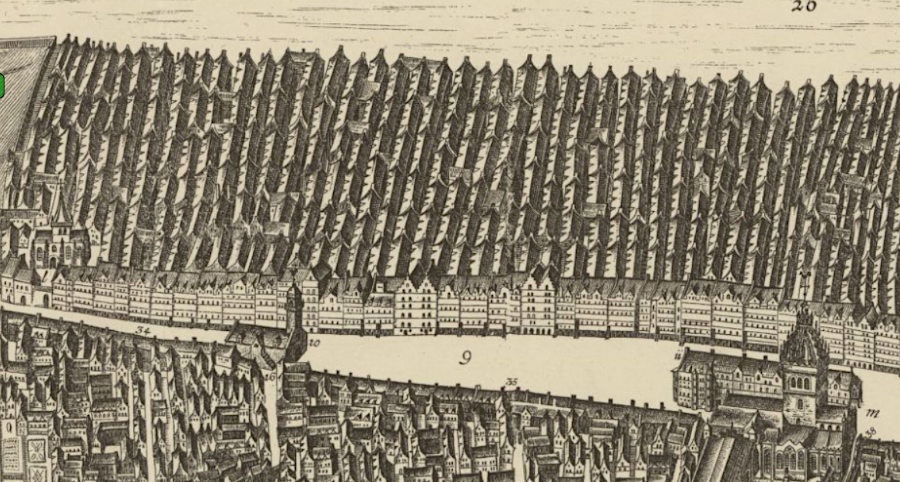

In medieval England and Scotland, thin and long strips of land were also used in towns to create "burgage plots" that maximized street frontage. Tenants on burgage plots were known as burgesses, and "Burgess" became a common English name.

narrow burgage plots in cities and towns maximized the number of landowners with street frontage

Source: National Library of Scotland, Bird's eye view of Edinburgh in 1647 (by James Gordon of Rothiemay, published 1870)

French land surveys were dramatically different from metes and bounds surveys in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Norman's chart of the lower Mississippi River (1858)

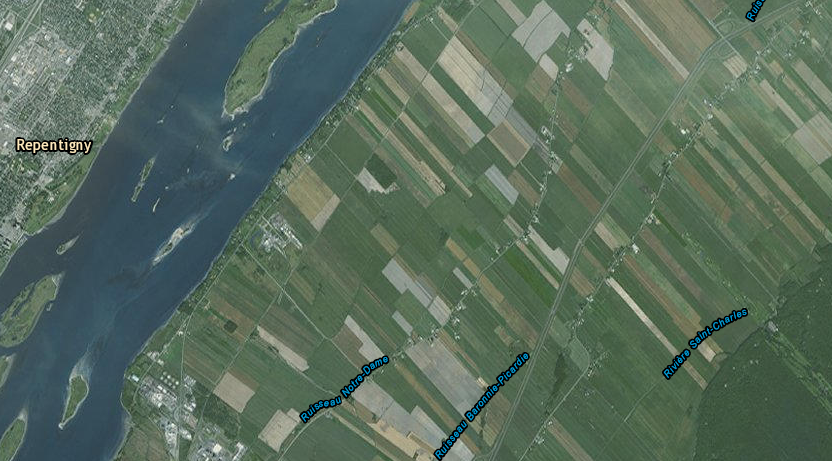

the French pattern of allocating land in narrow strips is still clear along the St. Lawrence River, just downstream from Montreal

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The French who settled in Virginia included Huguenot refugees escaping persecution in France for their Protestant faith, after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Others were Catholics who came up the Mississippi River to the Illinois Country, before that land was transferred to British control after the French and Indian War.

The Huguenots who arrived in 1700 were given land upstream of the Fall Line on the James River. There they would serve as a buffer against attacks by Native Americans on English settlements downstream. The refugees at Manakin Town were visited in 1702 by Francis Louis Michel, who noted the pattern of land ownership reflected their traditional approach of creating thin strips:4

Kaskaskia was part of Virginia's Illinois County between 1778-1784, but French settlers there surveyed land in traditional strips that provided river frontage to everyone - in contrast to how George Washington had his land grants on the Kanawha River surveyed, so he controlled the high-quality bottomland

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, A French Settlement: Kaskaskia, Illinois, Specimen of Common Fields, about 1809 (Plate 52b) and Grant to Washington for Military Services, 1774 (Plate 51b), digitized by University of Richmond)

A survey and a land patent were valuable documents in legal contests, but the boundaries had to be identifiable on the land as well. Today, iron pins are drilled into the ground to mark the turning points and other nodes on the boundary lines, often with plastic ribbons to flag or highlight the location of the pins. In colonial times, slashes on trees made by hatchets/axes and scratches on rocks would fade over time, as would the memories of people who were familiar with the original survey lines.

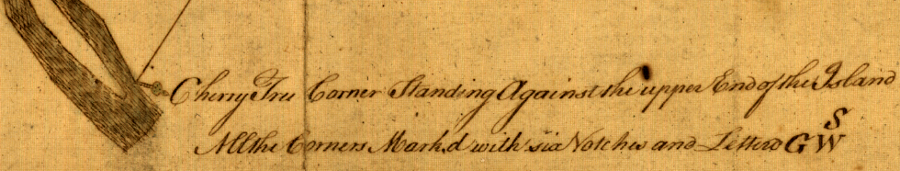

six notches in a cherry tree, plus three letters, marked the edge of a 1774 survey done for George Washington in Botetourt County

Source: Library of Congress, Copy of a survey return'd by Mr. Sam Lewis, surveyor of Botetourt Coun[t]y. Surveyed for George Washington 2950 acres of land

The solution to fading marks and memories was a requirement adopted in a 1662 law to "process" the boundary lines. The local Anglican parish vestry would organize local landowners and neighbors to walk around the boundaries of separate parcels. Disputes between adjacent property owners would be debated and resolved in the processioning, reinforcing the community's understanding and minimizing the need for lawyers to debate boundaries in courthouses.

A 1705 law required the county courts to issue orders every four years for processioning to be completed between September 30 and March 31. Property boundaries accepted after three cycles (12 years) were considered final and required no more processioning.5

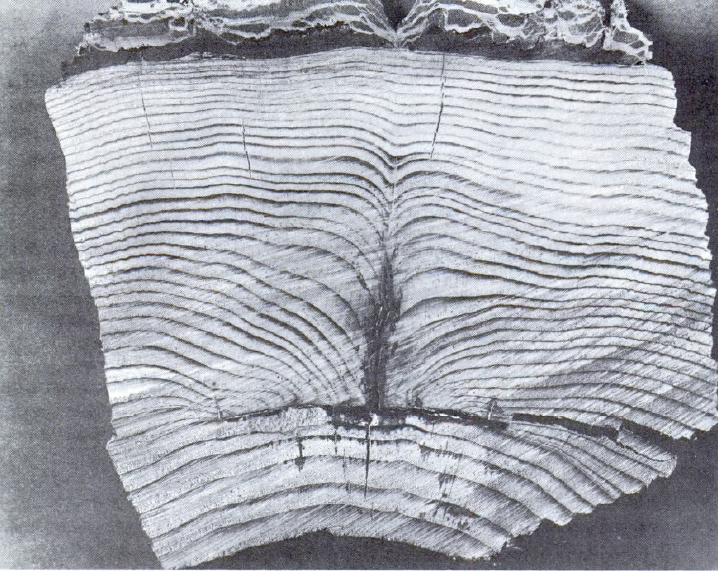

trees scarred by a hatchet blaze during a survey healed over, but could be identified years later and help surveyors re-mark the boundaries

Source: US Geological Survey, Boundaries of the United States and the Several States (by Franklin K. Van Zandt, Geological Survey Bulletin 1212, 1966, p.138)

To vote in Virginia, you had to own land. The "freehold" requirement ensured that the electorate would have conservative inclinations - the assumption being that those who own property in an area are less inclined to raise property taxes and redistribute the wealth indiscriminately.

When Kentucky separated from Virginia and became the 15th state in 1792, its constitution did not require that voters had to own land. While this may have reflected some democratic tendencies, it was also a reflection that determining land ownership was impossible because:6

The endless legal disputes stimulated Thomas Jefferson to spur the Congress to establish the Public Land Survey System even before the Constitution was drafted, and long before a constellation of satellites established the Global Position System (GPS).

Jefferson's survey-before-sale approach was intended to prevent the complications regarding land owmnership that were created by the traditional metes and bounds surveys in Virginia, where settlers selected the best parcels and legal disputes regarding the legitimacy of surveys were common. Surveys created slices of unclaimed, low-quality land ("gores") that was hard to sell, reducing revenue to the colony.

When Virginia ceded its claim to the Northwest Territory in 1781, in part to stimulate Maryland to sign the Articles of Confederation, the General Assembly retained a slice of land between the Scioto and Miami rivers. The Virginian Military District was used to provide land grants to Revolutionary War soldiers. Though most of the Northwest Territory was surveyed in grids to define townships and ranges according to the Public Land Survey System, metes and bounds surveys were common within the Virginian Military District.8

metes and bounds surveys defined land grants in the Virginia Military District, now a part of Ohio

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Specimen Surveys in the Virginia Military Reserve Ross County, Ohio, 1799-1825 (Plate 41e, digitized by University of Richmond)

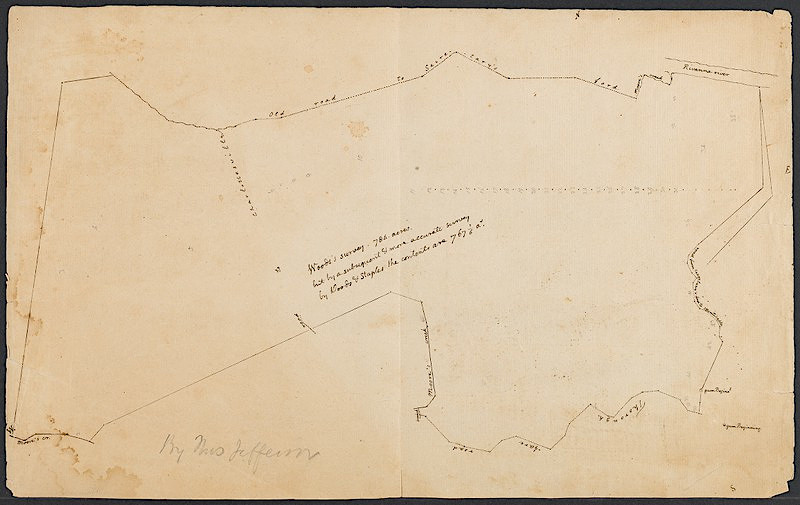

survey by Thomas Jefferson of wooded tract between Monticello and Rivanna River

Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University, Survey map of plot in Virginia, near Charlottesville

the road from Monticello to Secretary's Ford surveyed by Jefferson now passes by the Moores Creek Advanced Water Resource Recovery Facility

Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University, Plat of the James Barbour patent of 5,012 A. and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

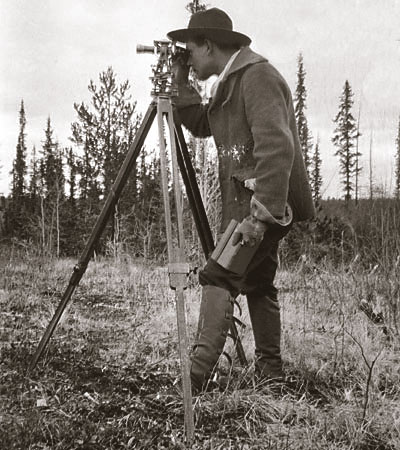

colonial-era surveyors had no radio or Global Position System technology

Source: US Forest Service, Land Ownership and Boundary Adjustment

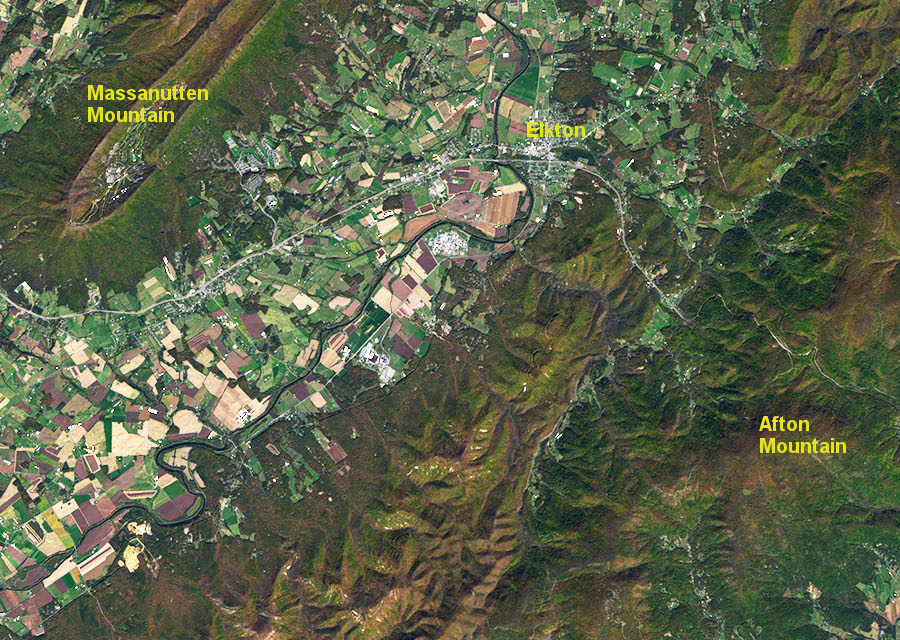

land near Elkton in the Shenandoah Valley was surveyed with metes-and-bounds boundaries and has been farmed since the mid-1700's, while property boundaries are nearly invisible on the nearby mountains with thin soil

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, The Sinuous Shenandoah

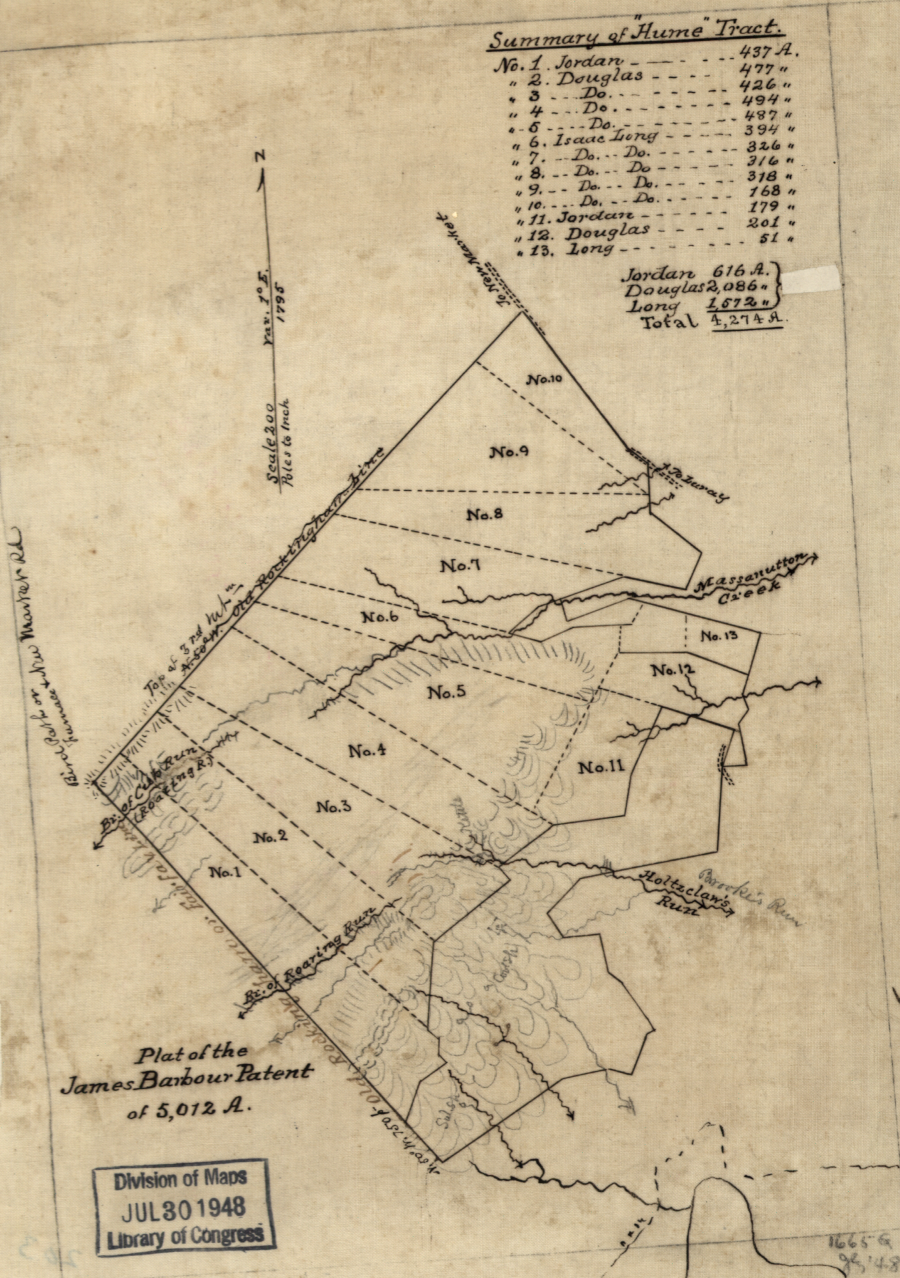

colonial and state officials desired surveys where boundaries of tracts were shared, leaving no unclaimed spaces between parcels

Source: Library of Congress, Plat of the James Barbour patent of 5,012 A. (1870's?)