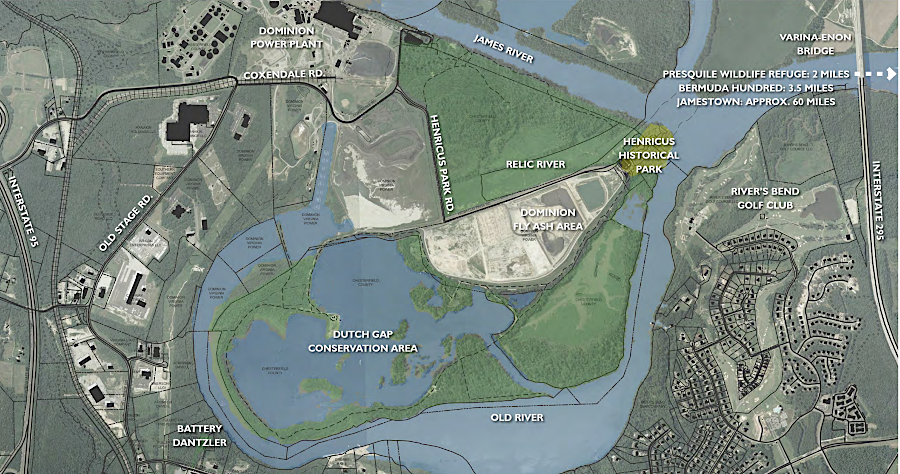

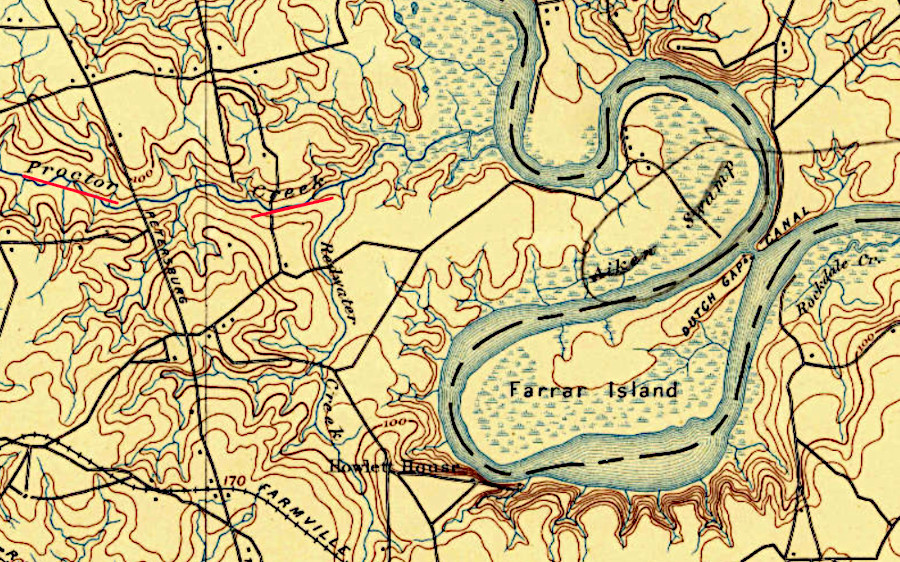

a recreation of the 1611-22 town of Henricus is located on Farrar's Island, next to Dutch Gap Canal

Source: Henricus Historical Foundation, Henricus Master Plan (p.15)

a recreation of the 1611-22 town of Henricus is located on Farrar's Island, next to Dutch Gap Canal

Source: Henricus Historical Foundation, Henricus Master Plan (p.15)

The Virginia Company adopted a new strategy for its colony after the Starving Time in the winter of 1609-10. Efforts to establish a peaceful relationship with Powhatan were abandoned, replaced by harsh "Irish tactics" to brutally occupy Native American towns and force the warriors away from Jamestown.

After the Starving Time, the settlers openly revealed their intent to permanently establish new settlements. The colonists would no longer rely upon local inhabitants to trade for food; corn would be seized, collected as tribute, or acquired from towns outside of Powhatan's control.

Starting in 1610 the English forced the Algonquians-speaking Native Americans to abandon territory which Powhatan claimed as part of Tsenacomoco. The yi-hakins of various tribes were burned, temples were desecrated, corn fields were flattened, and men/women/children were killed without mercy as the English destroyed towns and expanded their control over Tsenacomoco in the James River watershed.

Sir Thomas Dale was sent to Virginia to "reboot" the colony and create Virginia 2.0. He was given authority to act as governor if the appointed governor (Lord De La Warr) and the lieutenant governor (Sir Thomas Gates) were not available. Dale served as governor from his arrival in March 1611 until Sir Thomas Gates returned in August of that year, and again from March 1614-April 1616. When not serving as governor, after March 1612 Dale was a member of the Governor's Council.

Dale was the marshal responsible for enforcing martial law. He issued his Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall on June 22, 1611. To spur compliance with his commands, he ordered that one colonist be tied to a tree until the man starved to death.

Powhatan failed to organize a military response to the English raids on tribal homelands in Tsenacomoco. The English had greater mobility and concentrated firepower. They used their ships to quickly transport soldiers who overwhelmed the Native American defenders, starting with the Nansemond, Paspahegh, and Appamattuck in 1610-1611.

Powhatan and his war chief Opechancanough were unable to mobilize enough warriors to offer effective resistance to protect the towns in the paramount chiefdom, or to attack the English in their palisaded settlements. Dale's military success led to the end of the first Anglo-Powhatan War in 1614. Powhatan decided that it would be better to accept peace, despite the loss of territory and displacement of towns. The marriage of Pocahontas and James Rolfe gave Powhatan an opportunity to re-set the relationship with the English, and peace lasted for eight years.

One part of the new Virginia Company strategy adopted after the 1609-1610 Starving Time was to establish a new capital to replace Jamestown. The Spanish as well as the Native Americans were a serious threat, and the Virginia Company directed from London that the colonists find a location better protected from an attack by Spanish ships.

In anticipation of a Spanish assault, soon after he arrived on May 12, 1611 Sir Thomas Dale ordered construction of Fort Charles and Fort Henry at the mouth of the Hampton River to supplement Fort Algernourne on Point Comfort. His timing was good. In June, a Spanish ship anchored off Point Comfort and three sailors came ashore, including Captain Don Diego de Molina. They ended up as captives of the English when the ship sailed away. In the end, King Philip III of Spain never ordered an attack to destroy the colony of the Virginia Company.

For a safer location further inland, Dale selected a narrow peninsula along the James River. The site for a new capital was 17 miles upstream from the mouth of the Appomattox River, and 13 miles downstream from the Fall Line. In contrast to Jamestown, the peninsula offered a reliable supply of fresh water.

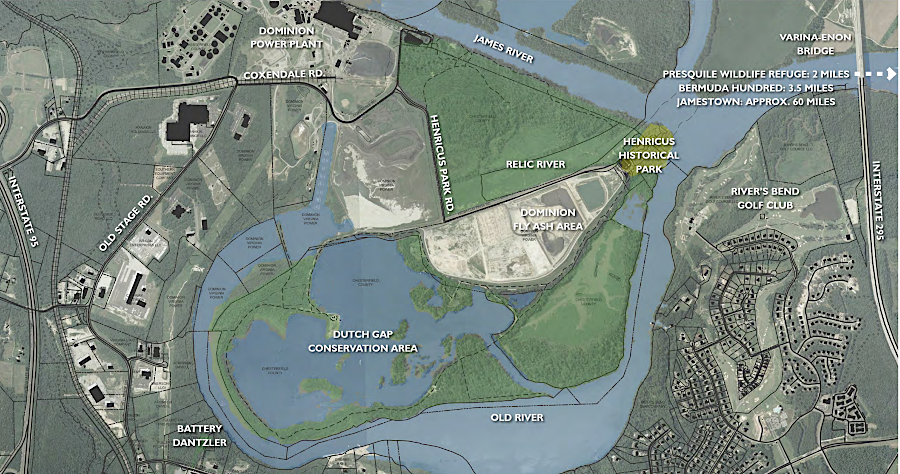

Dale chose the site for the new town of Henricus in the territory of the Arrohateck in 1607. By 1611, the peninsula was either deserted or quickly evacuated by the Arrohateck.1

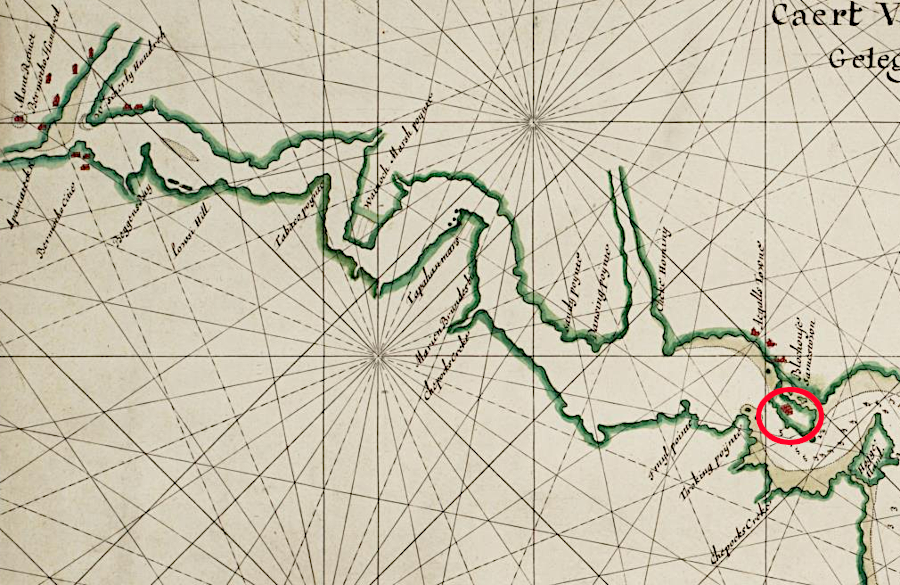

in 1611 Sir Thomas Dale located Henricus near the location of the former town of Arrohateck

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1612)

For the Spanish to sail up the James River to the site of Henricus, they would have to bend back and force around what is known today as Presque Isle, Curles Neck, and Jones Neck. Archers on the bluffs could harass any attackers, as the Native Americans had demonstrated multiple times against English ships. The English could haul small cannon to those bluffs as well.

The migration to the chosen location for the colony's third settlement (after Jamestown and Kecoughtan/Hampton) started when Sir Thomas Dale sent 300 men to march along the northern bank of the James River in August 1611. Dale himself sailed upstream with the supplies and more men to the peninsula. He named the new town Henricus to honor the heir to the English throne, Prince Henry. Henry died before his father, King James I, so the next king ended up being his younger brother Charles I.

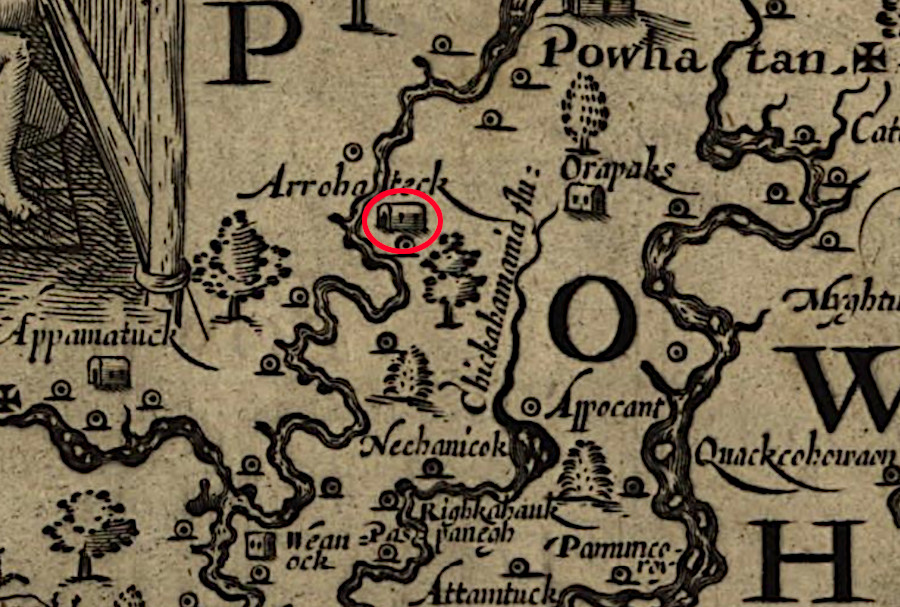

To defend against Powhatan's warriors, Dale had a palisade constructed across the narrow neck of the peninsula to block the Native Americans from accessing Henricus from land. Dale had built fortifications in the Netherlands before signing on with the Virginia Company, and directed that a ditch be dug outside the wall to make the defense stronger. The site of the ditch became known as "Dutch Gap."

That palisade may have been located at the parking lot of the modern Henricus Historical Park, or perhaps where the Dutch Gap Canal was built in 1864. No one knows for sure. Archeology at the site is challenging in part because so much clay was deposited on the original surface when the Dutch Gap Canl was built.

Behind the palisade, the settlers erected a fort with houses and a church. The palisade protected seven acres, providing far more protected space than the 1/2 acre within the walls at Jamestown. According to the Virginia Company the first stories of the houses were constructed with brick, demonstrating permanence of the settlement and its elevated status as the "new" capital compared to Jamestown.

However, drying and firing clay would have required time as well as labor. More likely, walls at Henricus were made using wattle and daub while roofs were constructed from thatch. Those materials were readily available, and construction did not have to be delayed for the production of brick.

the reconstructed church at Henricus Historical Park, like other buildings, was made using wattle and daub for walls and a thatch roof

In December 1611, Dale displaced the Appamattuck from their towns on the south bank of the James River near modern City Point. The south bank of the James River was considered safe for settlement, after using force to seize control of desired land and push the Appamattuck away from the company's houses.

Source: LionHeart FilmWorks, "Beyond the Palisade: Life in 17th Century Virginia" (2006) Colonial History Documentary

Across the James River in what the English named Coxendale, workers erected a hospital building. Mount Malady, also known as Mt. Malado, was large enough to hold 80 people. The Virginia Company expected passengers who traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to be unwell when they arrived in Virginia. A brief stay in the hospital would help the passengers recover, then get to work as indentured servants. Workers who suffered from dysentery, typhoid, malaria, and other illnesses could also recover more quickly if provided care in the hospital.

visitors at Henricus Historical Park can explore a reconstruction of Mount Malady

The Virginia Company chose to place the hospital at Coxendale rather than Point Comfort, where ships could first land. As indentured servants became fully capable, they could help develop the new capital at Henricus. Though Mount Malady was not within the fort at Henricus and protected by the palisade across the peninsula, Dale considered it to be in a defensible location. Keeping sick passengers away from the healthy people in the fort may have another consideration.

passengers recovering at Mount Malady stored their belongings underneath beds that were at least three feet high

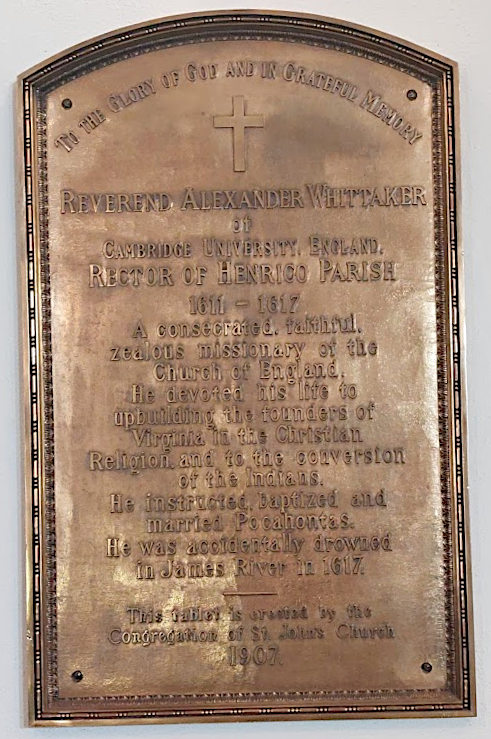

Also at Coxendale, a house was constructed for Rev. Alexander Whittaker. He named his parsonage Rock Hall. When Pocahontas was entrusted to his care for nine months after Samual Argall had seized her, she was instructed in the doctrines and rituals of the Christian faith and taught English culture.

Pocahontas would have spent much time at Rock Hall, though always accompanied by another woman when in the presence of a man. John Rolfe's courting of Pocahontas presumably followed English customs in order to result in official approval of their marriage, though some Native Americans claim she was sexually abused while in captivity.

Mount Malady and Rock Hall were constructed at Coxendale, across the James River from Henricus

Source: Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker, Virginia Under the Stuarts, 1607-1688 (p.20)

Rev. Whittaker baptized Pocahontas after she adopted Christianity. That event apparently was apparently at the church in Jamestown, where Pocahontas and James Rolfe are also thought to have been married, but interpreters at Henricus and Jamestown each highlight the possibility of those events occurring at their location.

The church was in the fort, unlike Rock Hall. Rev. Whittaker had to row across a short stretch of the river each day to provide services. In 1617, he drowned while making that journey.2

a plaque honoring Rev. Whittaker is in Richmond on the wall of St. John's Church, which traces its origins to the 1611 church at Henricus

Pocahontas lived at Henricus in late 1613-early 1614. Captain Samuel Argall kidnapped her when buying corn from the Patawomecks in 1613 and brought her initially to Jamestown. When it became clear Powhatan would not ransom her quickly, she was transferred to Henricus. Rev. Whitaker educated her in his Anglican version of the Christian faith and acculturated her in English customs.

Pocahontas converted to become an Anglican while living at Henricus and was baptized there. She also, according to the English, fell in love with John Rolfe. He was a widowed planter who had developed tobacco as a cash crop.

a painting in the US Capitol portrays Reverend Alexander Whiteaker baptizing Pocahontas, though the Anglican churches at Henricus and Richmond had no marble columns

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Baptism of Pocahontas (by John Gadsby Chapman, 1840)

Samuel Argall brought Pocahontas by ship up the Pamunkey River to Matchcot to discuss returning her, in exchange for English tools and weapons acquired by the Native Americans plus all Englishmen who had deserted or been captured. Opechancanough rather than Powhatan led the discussions, and was unwilling to make the bargain Argall offered in order to "rescue" Pocahontas. Opechancanough accepted the claim that Pocahontas wanted to marry Rolfe rather than be released in exchange, and Argall's demands were not met. As a result, Pocahontas was returned back to Henricus.

She married Rolfe on April 5, 1614 at the church in Jamestown, becoming Lady Rebecca Rolfe. Either Rev. Whitaker or the other Anglican minister in the colony, Richard Bucke, performed the ceremony. After that event, she moved from living at Henricus to his plantation.

An alternative version told by the Pamunkey is that Pocahontas was not willing to become part of English society. The alternative version claims she was raped by Sir Thomas Dale while a prisoner at Henricus. The birth of her son Thomas was not officially recorded, though her marriage was documented officially. The omission leaved open the possibility that the child was not conceived with Rolfe after marriage, though Thomas reportedly was born in 1615.3

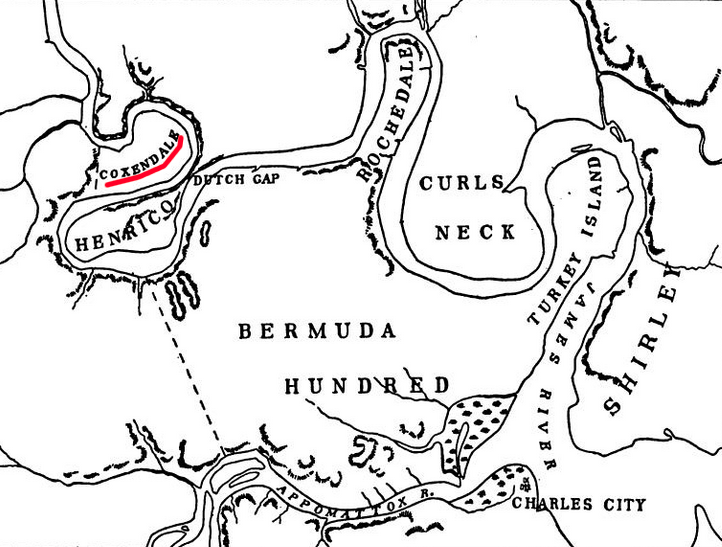

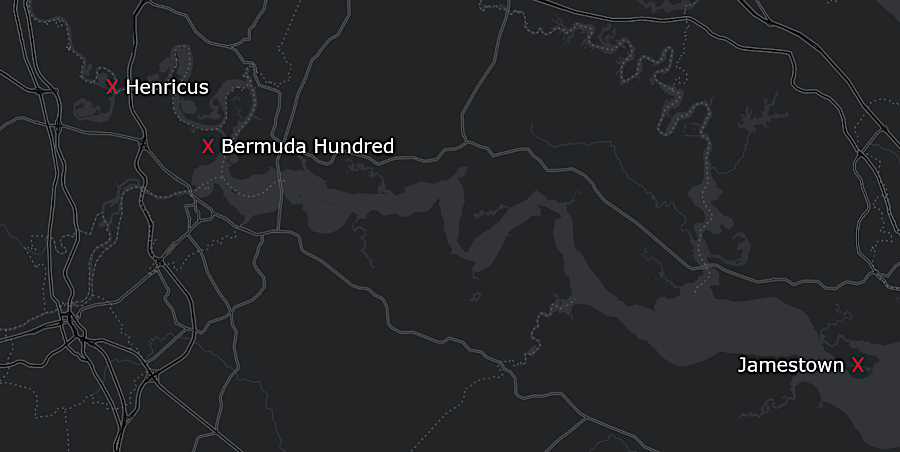

Henricus was not the only new settlement extending English control beyond Jamestown. Sir Thomas Dale forced the Appamattucks away from their main townsite at the confluence of the Appamattox and James rivers in 1613. He established a plantation there, Bermuda Hundred, named after the island where leaders of the Virginia colony had been stranded after a shipwreck during the winter of 1609-10. Bermuda Hundred was also protected by a palisade, two miles long.

Sir Thomas Dale developed plantations near the mouth of the Appomattox River, upstream from Jamestown (red circle)

Source: Dutch National Archives, Caert van de rivier Powhatan geleg(en) in Nieuw-Nederlandt (by Johannes Vingboons, c.1665)

John Rolfe, with his new wife "Rebecca" after their marriage, lived nearby at his Varina plantation. The deputy governor, Sir George Yeardley, and the lieutenant governor, Sir Thomas Gates, chose to live at Bermuda Hundred rather than at Henricus or Jamestown. So did Samuel Argall when he became governor.

The population increased at Bermuda Hundred as the Virginia Company offered land there to new settlers, and agreed to grant freedom to indentured servants of the Virginia Company after working there for only three years. When the various plantations along the James River each sent representatives to the first General Assembly meeting in 1619, Henricus sent Thomas Dowse and John Polentine/Pollington - but none came from Bermuda Hundred.4

Sir Thomas Dale established Henricus in 1611 and Bermuda Hundred in 1613, expanding English control over the James River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1618 the Virginia Company allocated 10,000 acres near Henricus to support a planned University of Henrico. The school was intended to educate, acculturate, and convert to Christianity the children that local Native Americans would entrust to the company.

George Thorpe, an investor in the Virginia Company, arrived in May 1620 to take responsibility for the university. To provide Thorpe an income, the company granted him 300 additional acres and 10 indentured servants to farm the land. He had his laborers distill some corn, brewing perhaps the first bourbon in North America.

Thorpe met with Opechancanough in 1621 to get support for the school. Opechancanough appeared to endorse conversion and amalgamation of his people with the colonists, starting with the young children to be educated in English ways. However, that appearance was a masquerade, part of Opechancanough's successful effort to lull the English into thinking the current peace would be permanent.

Henricus and other colonial settlements were attacked in the March 22, 1622 uprising. George Thorpe was at Berkeley Hundred, and he was killed and mutilated there. All of the settlers at Henricus were killed or forced to retreat to Jamestown, and the structures at Henricus were burned.5

Just upstream of Henricus, Alice Proctor and her indentured servants defended her plantation for three weeks from the fortified house. The colonial governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, finally required her to retreat to Jamestown. She and her husband John Proctor (who apparently was in England during the 1622 uprising) ended up being granted new land at Paces Plantation across the James River from Jamestown, on land from which the Quiyoughcohannock had been displaced.

According to tradition, in 1622 a Native American who had converted to Christianity, Chanco, warned Richard Pace of the impending uprising. Pace rowed across the river and alerted Jamestown in time to successfully ward off the attack. Had Jamestown been destroyed in 1622, continued English colonization in Virginia could have been postponed for years.6

Source: Henricus Historical Foundation, https://youtu.be/nQoZ_5WxsGY?si=XXrtVvnWIgnGvb2L

Alice Proctor defended her plantation in 1622 along what is still called Proctor Creek

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bermuda Hundred VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1894)

The Virginia Company did not fund rebuilding Henricus and staffing it with new indentured servants. The company's investors had received no profits since 1606 and lacked the resources to continue funding new development. Henricus was abandoned just 11 years after it was founded. Individual settlers like the Proctors relocated to more-secure locations.

Even before the 1622 uprising orchestrated by Opechancanough, colonists in Virginia had expanded private plantations along the James River. The Virginia Company incentivized dispersed development by granting ownership of land to people who "ventured" personally across the Atlantic Ocean to the colony, or paid for the transport of others, with a headrights system implemented in 1618.

By 1616 there were only about 50 people living inside the Henricus palisade. In 1623, after the "massacre" as the English labeled the event, there were only 22 people living in 10 houses.

Two years after the 1622 uprising, the Virginia Company's charter was revoked. Virginia became a royal colony, but King Charles I demonstrated little interest in its management. In particular, he made no effort to support developing a government town like Henricus to replace Jamestown. The land cleared for Henricus was included in a 2,000 acre grant to William Farrar in 1637. The townsite became part of what was called Farrar’s Island, and regrew into ordinary woodland and farmland.7

In 1860, just before the Civil War started, a historian noted that the location of Henricus was still recognizable:8

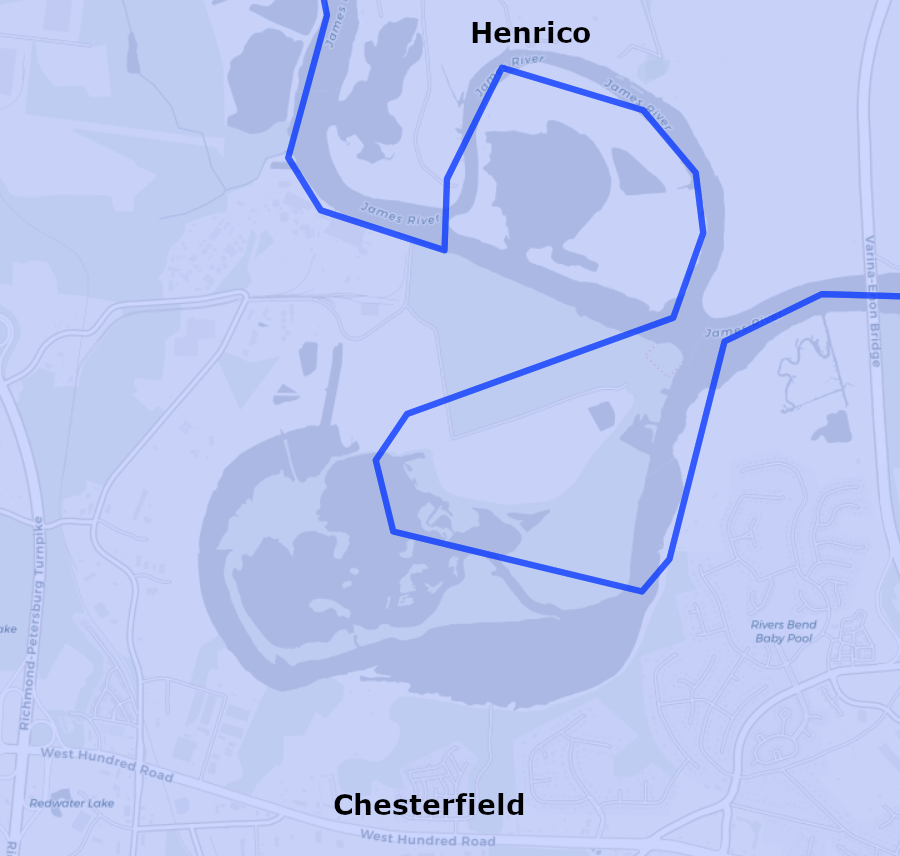

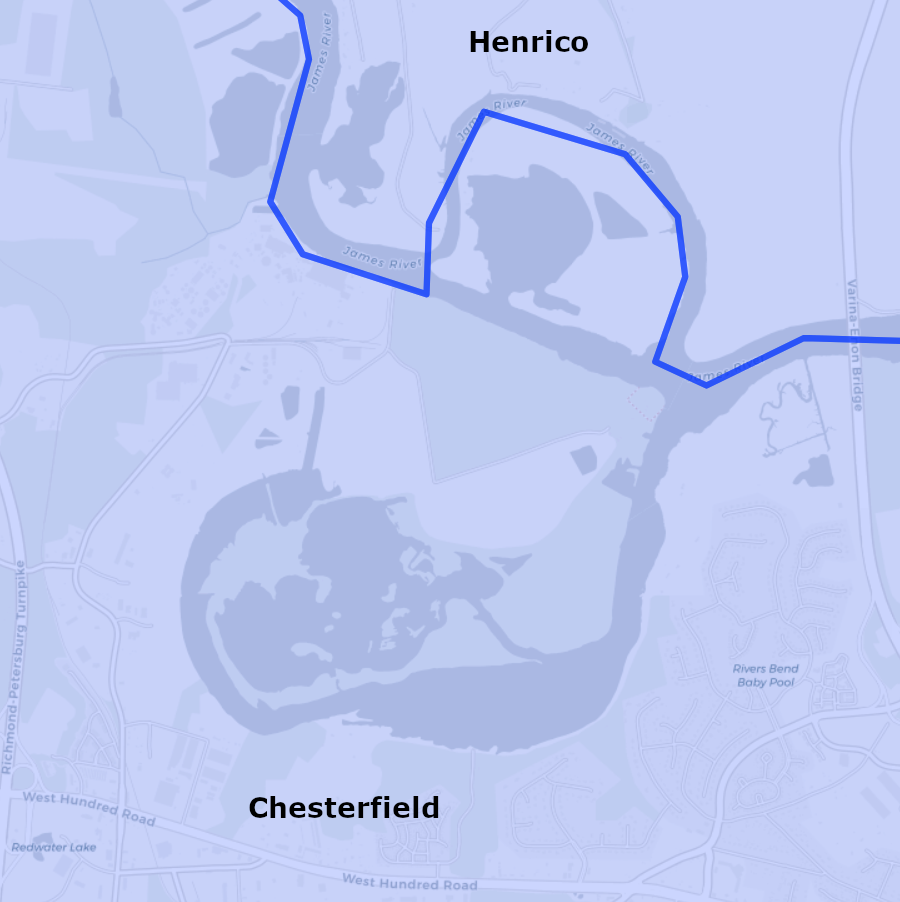

The excavation of the Dutch Gap Canal, started during the Civil War and completed initially in 1870, isolated Farrar's Island from Henrico County. In 1922, county boundaries were changed by the General Assembly and Farrar's Island was transferred from Henrico County to Chesterfield County.9

Chesterfield County annexed Farrar's Island in 1922, so the James River defined county boundaries again

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1985, a group of local residents formed the Henricus Foundation:10

The Henricus Foundation partnered with Chesterfield and Henrico counties. With funding from all three sources, they built a visitor center and replicas of the palisade and various buildings. At reconstructions of Mount Malady, Reverend Whittaker's house, and other structures, staff offered historical interpretation programs to school groups and the general public.

entrance to the reconstructed fort at Henricus Historical Park

The reconstruction was built on Farrar Island within Henrico County, next to Dominion Virginia Power's coal-fired Chesterfield power plant. Chesterfield County purchased the 810-acre Dutch Gap Conservation Area around it for the county's first passive recreation park in 1996. A boundary change later transferred the property from Henrico County to Chesterfield County.

a recreation of the 1611-22 town of Henricus is located on Farrar's Island, next to Dutch Gap Canal

Source: fosterh74, Citie of Henricus

In 1971, when the site was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, officials assumed that Henricus had survived construction of the Dutch Gap Canal. The current presumption is that the reconstruction may not be located exactly where Sir Thomas Dale constructed the first buildings in 1611, but is close. Archeological remnants may still exist underneath clay excavated during construction of the Dutch Gap Canal and other landscape alterations.

In 1971, park advocates believed:11

Henrico County decided in 2024 to stop funding Henricus Historical Park, after 25 years of support. The decision to eliminate the support, which amounted to 1/3 of the park's funding, was made late in the Henrico County budget process and caught Chesterfield County by surprise.12

Chesterfield County decided to make up the difference. As part of the changes, the Henricus Foundation transferred responsibility for the site to Chesterfield County and it became an official county park. One early action by the county was to pave the parking lot.

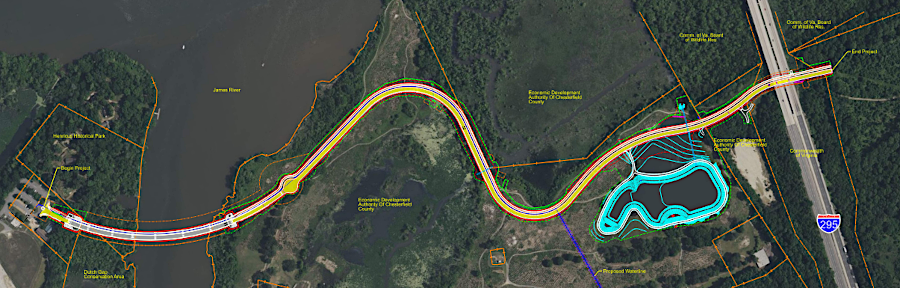

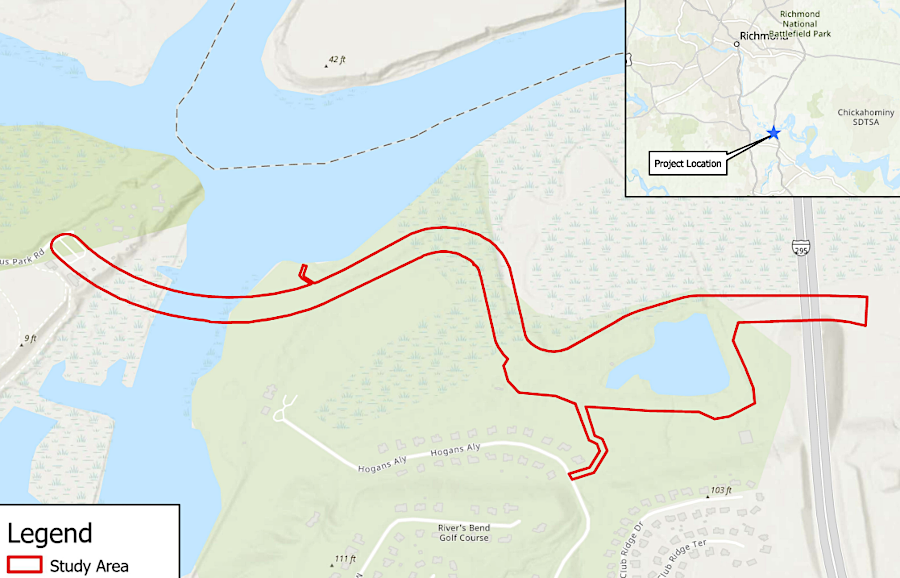

Chesterfield County and Dominion Energy also planned to change the access road. Coxendale Road was planned for closure as part of the project to remove coal ash at Chesterfield Power Station. A new bridge was planned across an oxbow of the James River that had not been used by commercial shipping since the Dutch Gap Canal was opened in 1871.13

a new access road to Henricus would require a bridge across an oxbow of the James River

Source: "June 2023 Henricus Access Road Progress Plan Layout," Chesterfield County, ; US Army Corps of Engineers, NAO-2021-03242 (Henricus Park Bridge Access, Chesterfield County, Virginia) (Figure 1)

visitors to the Citie of Henricus historical park drive past the fly ash pond of the Chesterfield Power Plant

Source: Henricus Historical Foundation, Henricus Master Plan (p.27)