Anglicans/Episcopalians in Virginia

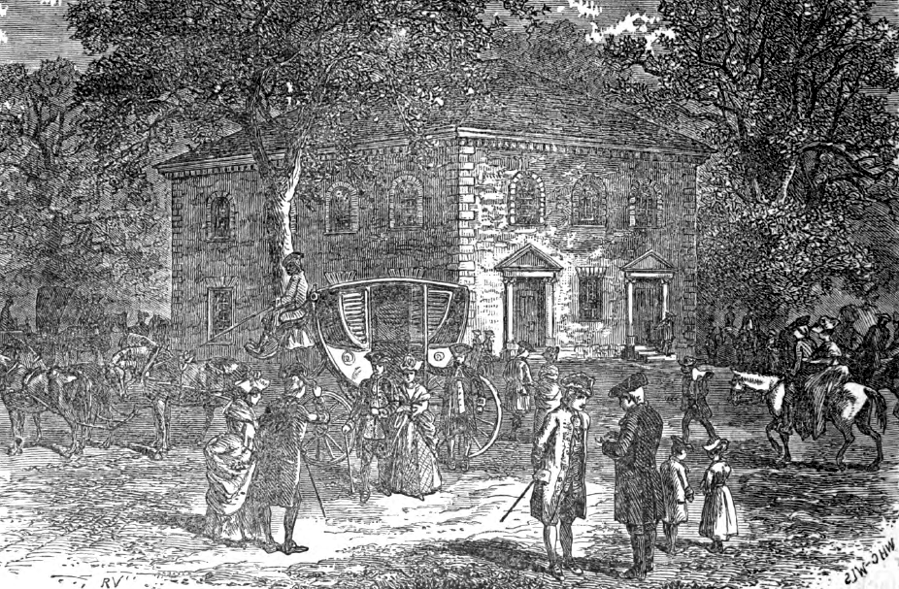

state and church were not separated in colonial Virginia - Anglican church buildings (such as Pohick Church in southern Fairfax County) and Anglican ministers were funded by mandatory taxes imposed by the vestry on local property owners

Source: Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland, Marshall House (p.15)

From the settlement of Jamestown until several years after the American Revolution, the Church of England (Anglican Church) was the official "established" church of colonial Virginia.

The head of state in England (i.e., the king or queen) had been head of the church as well for nearly 75 years before colonists arrived at Jamestown. King Henry VIII had separated England from the Catholic church in 1534, and the king in London replaced the Pope in Rome as the head of the church in England.

Consolidating power over church and state strengthened the monarchy. Henry VIII increased his wealth and power by seizing the monastaries and redistributing their land and wealth to his supporters. The government got to determine what religious beliefs and practices were acceptable, and to punish those it determined were guilty of heresy.

Parliament approved a Book of Common Prayer that was used in Anglican services. Ongoing rivalry in the 1500's, 1600's and 1700's with Spain, a Catholic country, highlighted the sense that religious differences were also political differences and that non-Anglicans were non-patriotic.

When Lord de la Warr imposed martial law in 1610, he mandated church attendance to establish control over the servants of the Virginia Company:1

- Services were held fourteen times a week, with sermons preached twice on Sunday and once on either Wednesday or Thursday. Two prayer services, one in the morning and one in the evening, were held Monday through Saturday... The Captain of the Watch was under instructions to

round up all persons, except those sick or injured, and bring them to the Church at the appropriate times.

Pocahontas had to convert to Christianity and be baptized (in the Anglican faith) before marrying John Rolfe

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Baptism of Pocahontas

Church services at Jamestown were held underneath canvas roofs and then in various structures, until a wooden church was completed in 1617. The outline of that structure, with a 20x50 foot brick foundation, was unveiled by archeologists in January, 2019. It was underneath the Memorial Church built in 1907.

They were in a hurry to complete their digging, because the 400th anniversary of the first General Assembly was planned for July. In 1619, the first New World legislature with members elected by colonists met in that Jamestown church building. At the time, there were no concerns about a government agency operating in a church; the concept of separating church and state evolved much later in Virginia.2

the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) was chartered in 1701

Source: Anglicans Online, The Seal of the Society for Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts

In the 1720's, German-speaking and Scotch-Irish immigrants began moving from Pennsylvania into the Shenandoah Valley. Virginia's governors welcomed them. Though not Anglican, they were Protestants and they filled up the backcountry. Settlement by colonists west of the Blue Ridge created a protective barrier to raids by Native Americans, and deterred the French from moving east out of the Ohio River Valley.

Some Anglicans in Tidewater also moved west of the Blue Ridge onto land grants, including some originally issued by Fairfax's land agent Robert "King" Carter. Cunningham's Chapel was built in 1747 in Frederick County. Its 1793 replacement, now known as Old Chapel, is the oldest Episcopal church west of the Blue Ridge.3

Large numbers of immigrants from Tidewater settled on eastern edge of the northern Shenandoah Valley late in the 1700's. The cultural differences in Frederick County between the area west of Opequon Creek settled by German/Scotch-Irish, and the eastern edge settled by traditional Tidewater immigrants (including Cunningham's Chapel), led to the creation of Clarke County in 1836.4

As the population grew west of the Blue Ridge, the General Assembly created both counties and parishes. In Virginia, the vestry managing parishes of the Church of England had civic responsibilities as well as the burden of managing church buildings and ministers. Civic duties included caring for orphans and the poor, documenting marriages so estates could be processed later, and "processioning" boundary lines to ensure neighbors recognized each other's private property. Boundaries were walked by neighbors three times, in a process overseen by the vestry, to establish clear title and minimize conflicts.

Where there was a high percentage of Scotch-Irish and German speaking immigrants, it was difficult to find enough Anglicans to fill all 12 seats on the parish vestry with responsibility to manage religious and civic duties. Non-Anglicans were chosen for many vestries west of the Blue Ridge, creating some tension since the colony had established the Church of England as the official church and designated the Book of Common Prayer as the official guide for worship.

When the vestry was first created in Augusta County, there were few Anglicans living in that part of the Shenandoah Valley. The region was occupied by immigrants coming from Pennsylvania and directly from Ireland, primarily German-speaking Pietists and Scotch-Irish Prebyterians. The General Assembly was petitioned to force dissidents off the vestry, but refused in part because there were too few Anglicans whio were qualified to serve.

As one history portrayed the circumstances:5

- It is said that the Presbyterians kept the Sabbath and everything they could get their hands on. This included control of the Augusta Vestry.

In the 1740's, the Great Awakening stirred religious passion in Virginia. Religious beliefs and practices were questioned; new rituals inconsistent with traditional Anglican practices were adopted. The number of dissidents expanded east of the Blue Ridge, including at the Polegreen church in Hanover County where Patrick Henry heard Rev. Samuel Davies preach. "New Light" Presbyterians, Moravians, and Baptist ministers were perceived by Anglican ministers as a threat to their authority.

In 1759, the General Assembly passed a law that clarified that dissidents could serve on a parish vestry in a jurisdiction in which dissidents were the majority. However, where Anglicans were the majority, the colonial legislature mandated that only Anglicans could serve on a vestry.6

There was typically a shortage of Anglican ministers in Virginia prior to the American Revolution, and the quality of them varied. It was difficult to recruit qualified ministers in England to serve in Virginia. Ministers recruited from Scotland and Ireland were not perceived as social equals with members of the gentry serving on the vestry, making the job less attractive.

Both pay and job security were low. Ministers were paid a salary in tobacco, but the value of that fluctuated annually a demand in Europe changed. The quality of the tobacco allocated to the minister was typically low, also reducing its value. Each parish had land, 100-200 acres known as the glebe, which was dedicated to producing revenue for the minister. Based on the quality of the glebe lands for raising crops and livestock and the availability of labor, some ministers could get a significant addition to their salary. On other parishes, the income-producing land glebe lands produced just marginal revenue.

Job security was also poor for Anglican ministers in the 1700's. After hiring a minister, vestries were supposed to send him to Williamsburg to be inducted by the governor. The governor acted as the highest ecclesiastical authority in Virginia, since the Church of England never sent a bishop to the colony. Governor Alexander Spotswood claimed the governor had authority to appoint the minister of a parish over the objections of the local vestry. He imposed his choice on the vestry of St. Ann's Parish in Essex County. After that minister soon left, no governor sought to override a vestry's decision.

Governor Alexander Spotswood forced his choice of minister on the St. Anne's Parish vestry, in which Vauter's Church is still located

Source: National Register of Historic Places, Vauter's Church

After induction by the governor, a minister was expected to stay at the parish for the rest of his lifetime. To retain flexibility and control of the minister, vestries avoid the induction process. They hired ministers on annual contracts, with the threat that the contract would not be renewed if the minister did not please the vestry. The risk of unemployment limited the potential that a minister might act independently from direction given by the vestry, or fail to acknowledge regularly the higher social status of the local gentry.

In England, only a bishop could dismiss an incompetent, drunken, or immoral minister from their office. In Virginia, there was no bishop; the commissary of the Bishop of London based at the College of William and Mary lacked dismissal authority. Empowering the governor or the General Assembly with the power to dismiss a minister would entangle lawmakers with administration of local church affairs.

Officially authorizing the vestry to fire a minister would upset the balance between Church of England officials and the laity, so a less-elegant approach was adopted without formal blessing by officials in England:7

- For much of the colonial period, the solution in Virginia was to hire ministers on a year-to-year contract. This facilitated removal of drunks, fornicators, and incompetents, but the price was subservience of the church to a local, self-perpetuating aristocratic body whose interests were not necessarily aligned with the gospel.

In 1749, after conflict between one vestry and its minister rose to the attention of the General Assembly, the colonial legislature set the standard pay for ministers in all parishes at 16,000 pounds of tobacco per year. The legislators also passed a law that essentially granted tenure to settled ministers. Those changes did not result in an increased number of ministers, or increased quality, and the conflicts between ministers and vestries increased in the 1750's.

Ministers for dissenting faiths demonstrated greater commitment to serving their members. They also practiced what they preached, and on average acted with higher morality than many Anglican ministers. In 1754, one Virginian sent a letter to the bishop of London contrasting the quality of Anglican and dissenting ministers, and how that difference was leading to a decline in the Anglican church:8

- My zeal for religion as proffes'd in the Church of Englad (of which I am a member) prompts me to add that it is easy to determine where it is the interest of the Church or that of the dissenters, is most likely to prevail here, where the former is promoted by some of the weakest and most worthless men; and th latter by men of sufficient learning adorned with piey and viryu.

In the 1750's, ministers saw an opportunity to get an unplanned financial benefit. The prince of tobacco climbed during a 1755 drought that occurred at the same time as the French and Indian War, inflating the value to triple the normal price. The General Assembly responded by passing a Two Penny Act. It allowed vestries to pay ministers as if the price was only two pennies (pence) per pound, rather than at the market price which reached six pennies per pound.

In 1758, weather again caused a shortage. The colonial legislature responded by passing the 1758 Two Penny Act. This time, the ministers objected. Rev. John Camm, funded by the Anglican ministers, traveled to London and got the Privy Council to disallow the 1758 Two Penny Act. However, the decision was not clearly retroactive and the law had already expired.

Nonetheless, three ministers sued to be paid full price for their service during the time the law was in effect. Rev. James Maury was the only one to win in court. When the jury was asked to decide how much in damages he would be paid, Patrick Henry delivered a fiery speech against the oppression of the clergy and of English officials in London, including King George III.

Henry's political carreer skyrocketed after his "Parson's Cause" speech. The Virginia gentry's relationship with Anglican leadership declined further when Rev. Camm got officials in London to invalidate the 1758 Two Penny Act. Hiring Camm to lobby the Privy Council in London was a direct challenge by the Anglican ministers to the elected officials in the House of Burgesses. That challenge reduced the gentry's support for the established church.9

The close association of the Anglican church with the royal government had a severe impact in the American Revolution. Boycotts of British-made goods shifted public support away from the established, official Anglican church. Ministers who were loyal to England lost the support of their vestries. Most ended up returning to England, and attendance at church services declined.

In 1776, the Fifth Virginia Convention adopted the Declaration of Rights, in advance of declaring independence from Great Britain and adopting the first constitution for an independent state of Virginia. Included in the Declaration of Rights was Section 16, stating:10

- That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practise Christian forbearance, love, and charity toward each other.

Dissenters, primarily Baptists east of the Blue Ridge and Presbyterians to the west, quickly began gathering names on petitions to the new state government calling for an end to the requirement to pay taxes for the support of the Anglican church. One petition, delivered on October 16, 1776, included a reported 10,000 names on 100 pages sewed together.

In response, the General Assembly suspended the requirement to pay for support of the Anglican church. Some of the power of the still-established Anglican church were limited in 1780, when the state legislature created county-operated Overseers of the Poor in seven western counties. Government officials rather than the Anglican vestry became the provider of social services.

In 1786, at Thomas Jefferson's urging and through the efforts of James Madison, the General Assembly passed the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom. It separated church and state, officially "disestablishing" the Anglican church. All counties then created Overseers of the Poor. The vestries welcomed the change; it relieved the Protestant Episcopal Church from the burden of managing social services for the government.11

The General Assembly had incorporated the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1784, allowing it to hold title to land and property in the name of the institution rather than in the names of individual church leaders or trustees appointed by a county court. Dissenting religions opposed incorporation, and under their influence the legislature in 1787 repealed the law incorporating the Protestant Episcopal Church.

To limit state support for religion, Virginia would not allow any church or religious denomination to incorporate for over 200 years. To buy and sell property, religious institutions had to establish trustees and obtain approval for transactions from the Circuit Court. That prohibition was overturned in 2002, when Rev. Jerry Falwell won a lawsuit and was able to incorporate Thomas Road Baptist Church.12

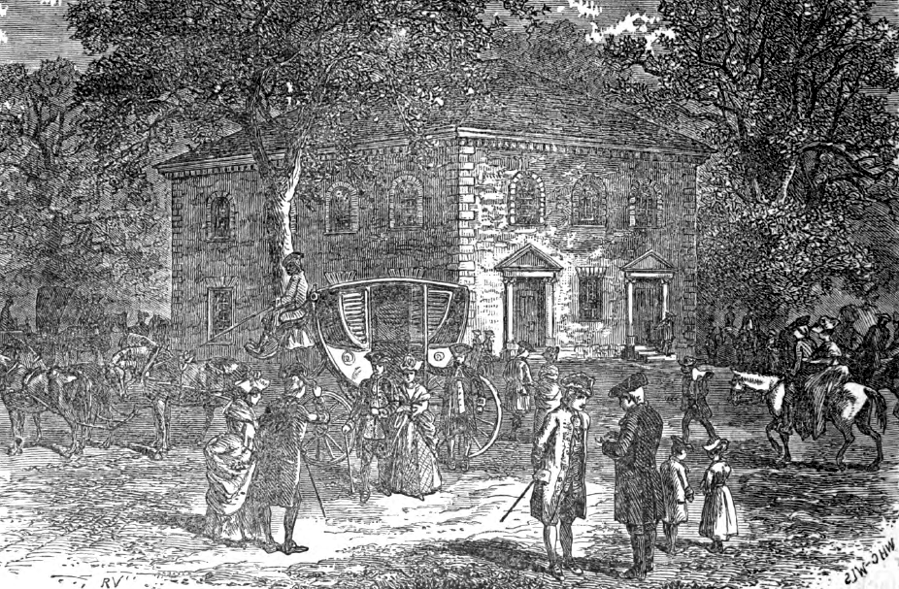

Starting on May 18, 1785, the Protestant Episcopal Church held its first official convention in Virginia. Episcopalians in each parish had elected a 12-man vestry to manage the parish's affairs, and each vestry had chosen two representatives to attend the convention. If the parish had a minister, he was automatically one of the two representatives. Purpose of the convention was to write canon law to replace the state statutes which had governed the church before its incorporation.

Of the 96 parishes in Virginia, 69 managed to send one or two representatives to the 1785 convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. There were 36 ministers and 56 representatives from the laity - including 20 who were members of the General Assembly. The delegates met in the Capitol building, which upset the leaders of dissenting churches in Virginia.

The new canon law empowered the 12-man vestries to manage the church, including the selection of ministers. Ministers were granted authority to vote as a member of the vestry. In addition, ministers were granted veto authority over decisions related to their glebe lands, which they managed to generate income to supplement their salary.13

The Episcopalians were tainted with the history of having been loyal to the King of England, treating him as the church's supreme authority on earth. After the high-energy Methodists formed their own separate denomination at the end of 1784, those who shared the theology and culture of the Episcopalians had an alternative, "loyal" church in which to worship.

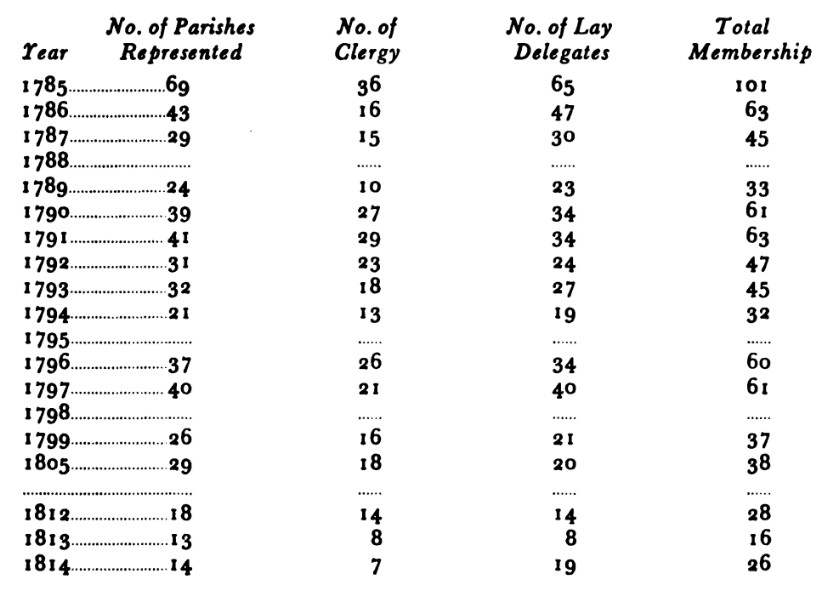

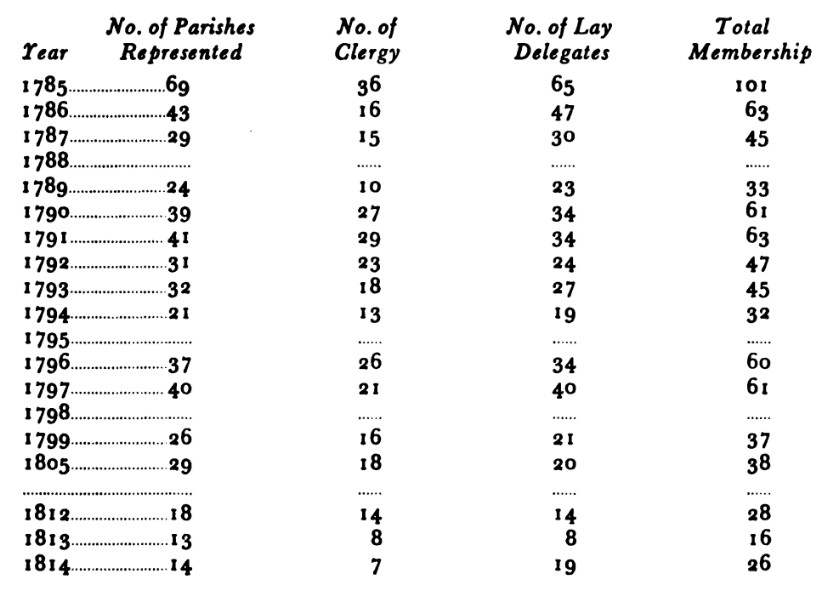

The decline of the Protestant Episcopal Church was reflected in the dwindling number of parishes represented in later Virginia conventions. Participation peaked in 1790 and 1791 with election of a new bishop, and in 1796 and 1797 as Baptist pressure to convert glebe lands to public purposes increased in the General Assembly.14

attendance at Protestant Episcopal Church conventions in Virginia

Source: George MacLaren Brydon, Virginia's mother church and the political conditions under which it grew, Marshall House (p.489)

There was a convention in 1803, but no records have survived.15

At the 1786 convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in Virginia, Rev. David Griffith was chosen to serve as bishop. He was supposed to travel to England with two other ministers from other states and be consecrated there. They would return with the chain of apostolic authority dating back to St. Peter, and from the new bishops a new generation of American ministers could be ordained.

However, the Virginians were unable to raise the funding required to pay for Rev. David Griffith's trip to England. He then resigned the office. Rev. James Madison, president of the College of William and Mary, was elected bishop in 1786. In 1790, Madison became the first Episcopal bishop to travel from Virginia to England and be consecrated.16

Links

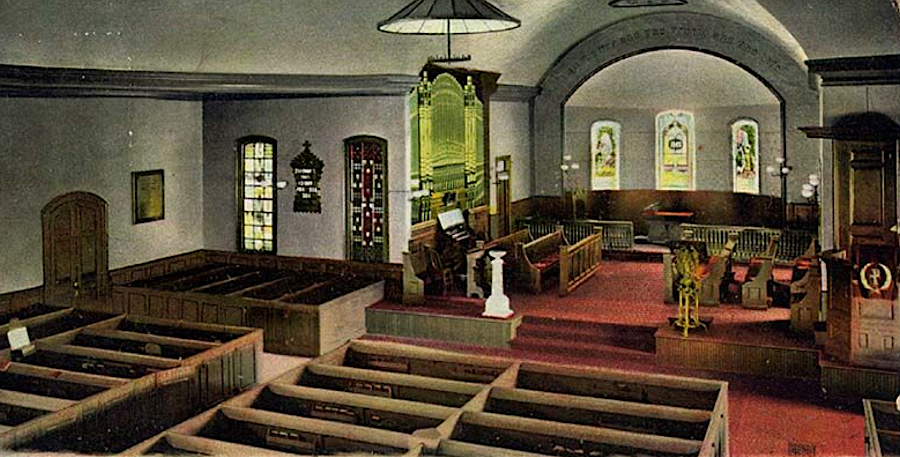

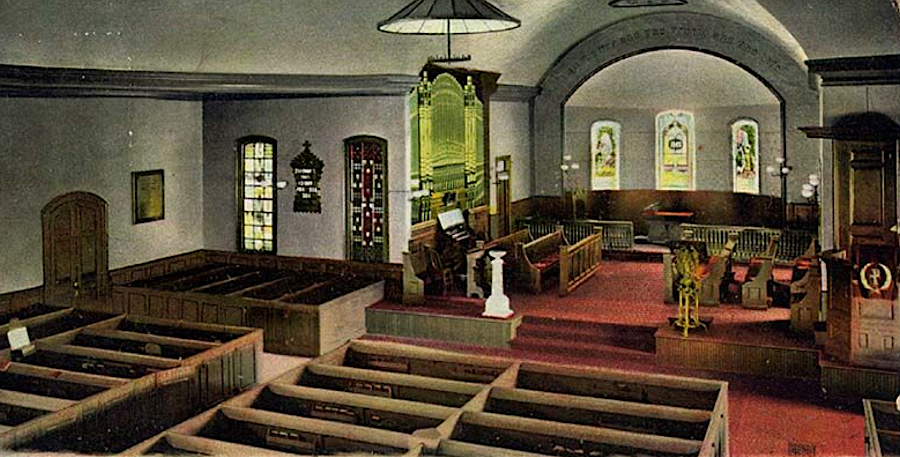

Patrick Henry gave his "Give me liberty or death" speech in 1775 at St. John's Church in Richmond

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, Interior of St. John's Church, Richmond, Va. (1906)

References

1. "Religion at Jamestown," Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, http://www.historyisfun.org/pdf/Background-Essays/ReligionatJamestown.pdf (last checked June 11, 2014)

2. "'We freaked out': Discovery at Jamestown sheds light on early English government in North America," The Virginian-Pilot, January 26, 2019, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/history/article_5e92c202-20ee-11e9-82a9-7b982f907ed3.html (last checked January 29, 2019)

3. "Old Chapel 021-0058," Virginia Landmarks Register, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Counties/register_Clarke.htm (last checked June 14, 2014)

4. "History," Clarke County, Virginia, http://www.clarkecounty.gov/local/history.html (last checked June 14, 2014)

5. Edward Aull, Early history of Staunton and Beverley Manor in Augusta County, Virginia, 1963, p.22, https://dp.la/item/f84d0307072c5abe46949bd6022365c1 (last checked July 3, 2025)

6. Rhys Isaac, "Religion and Authority: Problems of the Anglican Establishment in Virginia in the Era of the Great Awakening and the Parsons' Cause," The William and Mary Quarterly, Volume 30, Number 1 (January 1973), p.26, https://doi.org/10.2307/1923701; Edward Bond, "The Parish in Colonial Virginia," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, September 26, 2022, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/parish-in-colonial-virginia-the/ (last checked November 19, 2022)

7. Michael W. McConnell, "Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion," William and Mary Law Review, Volume 44, Number 5 (April 2003), pp.2141-2142, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1382&context=wmlr; "The History of St. Anne's Parish," Vauer's Episcopal Church, https://vauterschurch.com/our-history (last checked Novmber 23, 2022)

8. Rhys Isaac, "Religion and Authority: Problems of the Anglican Establishment in Virginia in the Era of the Great Awakening and the Parsons' Cause," The William and Mary Quarterly, Volume 30, Number 1 (January 1973), pp.6-10, https://doi.org/10.2307/1923701 (last checked November 18, 2022)

9. Jon Kukla, "Two Penny Acts (1755, 1758)," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, November 3, 2022, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/two-penny-acts-1755-1758/ (last checked Novembr 19, 2022)

10. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights," National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/virginia-declaration-of-rights (last checked September 22, 2022)

11. "'That The Oppressed May Go Free': A Petition To The Virginia General Assembly For Religious Freedom," UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2022/09/21/that-the-oppressed-may-go-free-a-petition-to-the-virginia-general-assembly-for-religious-freedom/; Robert M. Usry, "The Overseers of the Poor in Accomac, Pittsylvania, and Rockingham Counties, 1787-1802," Masters thesis, College of William and Mary, 1960, p.iv, https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dypj-e638 (last checked September 22, 2022)

12. "Falwell wins church-incorporation suit," Washington Times, April 17, 2002, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2002/apr/17/20020417-042025-9006r/ (last checked August 8, 2018)

13. George MacLaren Brydon, Virginia's mother church and the political conditions under which it grew, Volume 2, Virginia Historical Society, 1947, pp.452-465, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005947914 (last checked November 14, 2022)

14. George MacLaren Brydon, Virginia's mother church and the political conditions under which it grew, Volume 2, Virginia Historical Society, 1947, p.478, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005947914 (last checked November 14, 2022)

15. George MacLaren Brydon, Virginia's mother church and the political conditions under which it grew, Volume 2, Virginia Historical Society, 1947, p.478, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005947914 (last checked November 14, 2022)

16. "History," Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, https://www.thediocese.net/who-we-are/history/; George MacLaren Brydon, Virginia's mother church and the political conditions under which it grew, Volume 2, Virginia Historical Society, 1947, pp.445-452, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005947914 (last checked November 14, 2022)

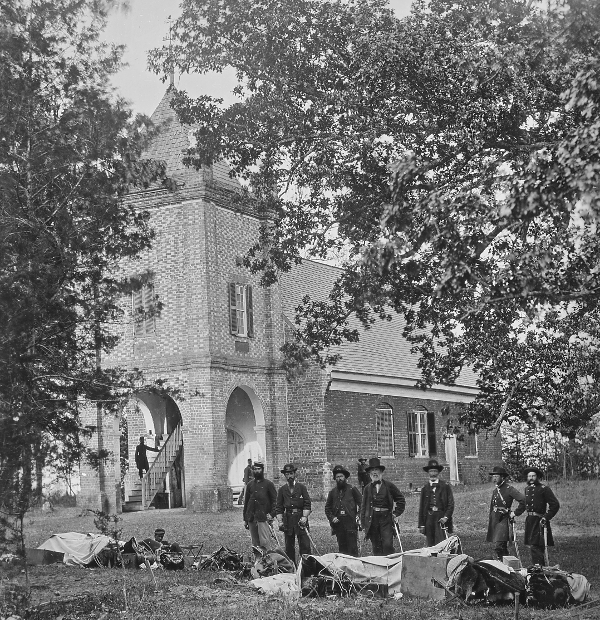

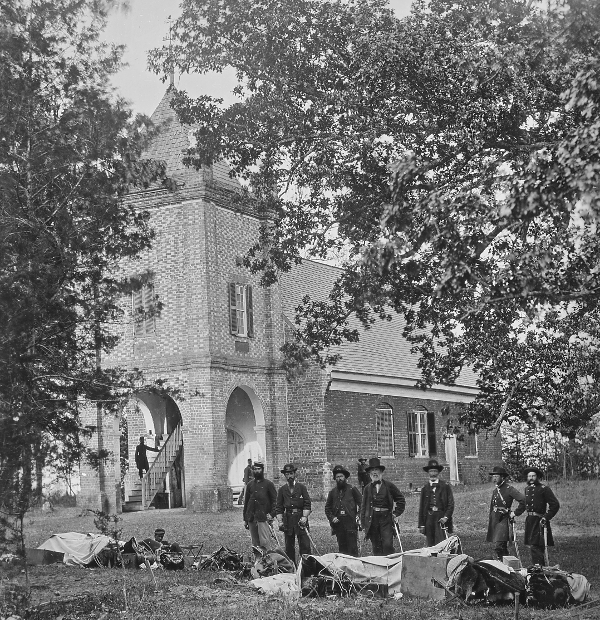

Martha Dandridge married her second husband, George Washington, reportedly at St. Peter's Church in New Kent County (which Union forces visited in the Civil War...)

Source: National Archives, St. Peter's Church, near the "White House", Virginia. (where G. Washington may have been married to Martha)

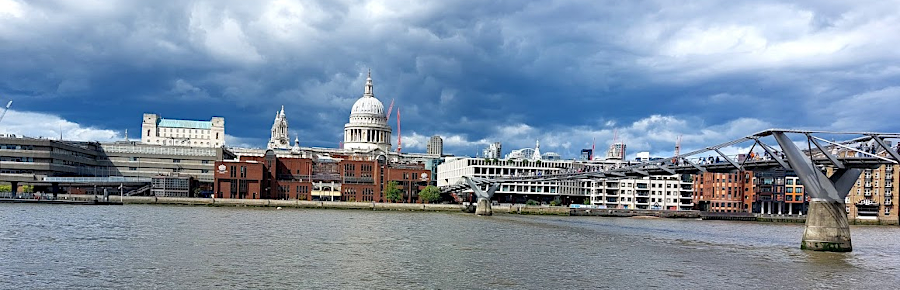

St. Paul's Cathedral still dominates the London skyline north of the Thames River, asserting Church of England authority

Religion in Virginia

Virginia Places