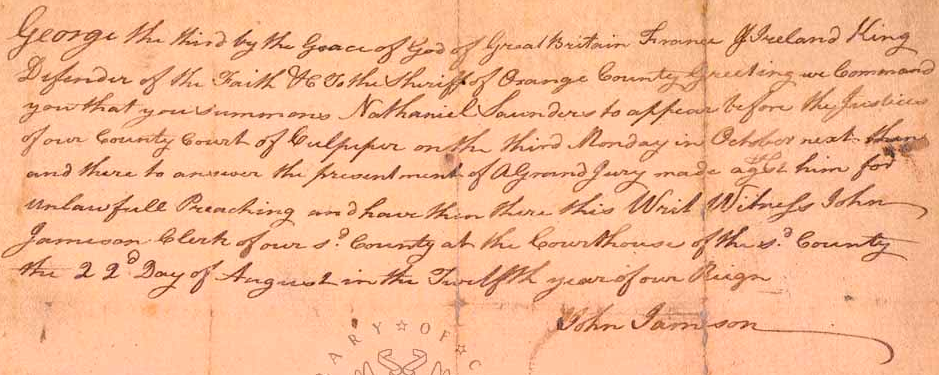

in 1772, the sheriff of Culpeper County was ordered to arrest a Baptist minister for "unlawfull preaching"

Source: Library of Congress, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772

in 1772, the sheriff of Culpeper County was ordered to arrest a Baptist minister for "unlawfull preaching"

Source: Library of Congress, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772

American citizens now assume they have an "inalienable right" to worship however they please, or even to choose not to have any religious beliefs. One standard joke illustrates the flexibility of American religious thought:1

Roman emperors persecuted Christians until the Edict of Milan was issued by Constantine and Licinius in 313 CE. Toleration did not last, however. After the Reformation, European rulers insisted that their subjects adhere to a single preferred religion. Failure to support the religion dictated by the ruler was viewed as treason.

Virginia was established as an Anglican colony. Religious freedom, or even tolerance, was not explicitly authorized by Virginia's government until 1786. That was a full decade after the Fifth Virginia Convention declared independence from Great Britain.

The king or queen of England was both head of the church and head of the state. Religious heresy was comparable to treason against the ruler. During the reign of Elizabeth I, when the English first tried to colonize North America, Catholic Spain was the political rival of Protestant England. Catholics tried to blow up James I and Parliament in 1605, but Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot failed.2

Just as in England across the Atlantic Ocean, the power of Virginia's government was united with the power of the Church of England (Anglican church) as an "established" religion.

Quakers were expelled from the colony by Gov. William Berkeley after he was restored to office in 1659, and non-Anglican preachers had to be licensed by the county court.

The American Revolution disrupted that traditional government structure and led to disestablishment of the Anglican church and official separation of church and state.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison led the charge to create legal guarantees for freedom of religious thought and practice. Modern courts must interpret their language to assess whether a law crosses a line and unconstitutionally assumes governmental power to interfere with a religion, or to support a particular religion.

Virginia was not settled by Europeans seeking to create a haven for religious liberty. The long history of European colonization in North America reveals that the desire for property and profit was the primary incentive for crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Though Virginia ended up being settled by members of the Church of England (Anglicans), the first colonists in North America and what became Virginia were Catholics.

Ponce de Leon brought Catholic priests with him to Florida in 1521, as part of the first European colonization effort in North America. Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon brought Dominicans in 1526, when he started the San Miguel de Guadalupe colony in what is now Georgia.3

The first Europeans who tried to settle in Virginia also were Catholics. Spanish Jesuits led by Father Juan Baptista de Seguera started the Ajacan settlement, near modern-day Yorktown, in 1570. The Native Americans there killed 10 of the 11 Spaniards in 1571; the teenage boy they let survive was rescued by a Spanish ship in 1572.4

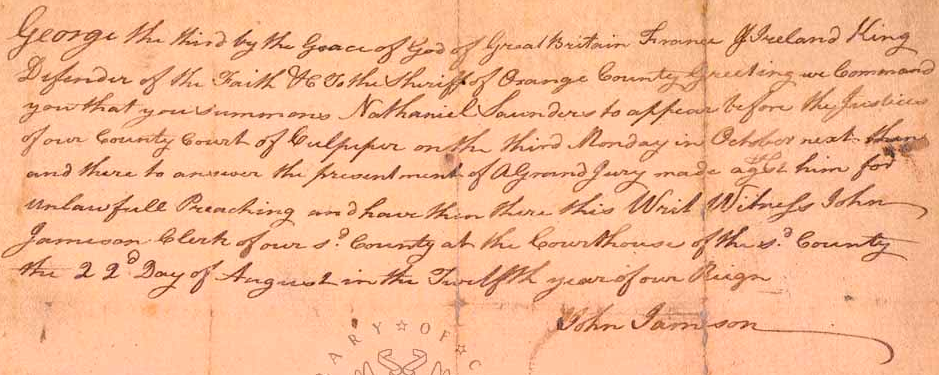

English colonization in Virginia was equivalent to Protestant colonization. One of the first actions by the initial English settlers when they arrived at Virginia was to build a wooden cross at Cape Henry. When Jamestown was founded in 1607, the Church of England (Anglican) was "established" in the colony of Virginia as the official church with King James I as the Defender of the Faith. Catholics would not be allowed to worship openly in Virginia until 1781, when French troops involved in the siege of Yorktown celebrated Mass in Alexandria.5

in 1935, National Society Daughters of the American Colonists installed a granite replica of the wooden cross erected in 1607 at Cape Henry

Source: National Park Service, Cape Henry Memorial Cross

Virginia's Protestant gentry became well-entrenched in county courts, the House of Burgesses, and also in Anglican vestries The vestry was the governing board of a parish. Members of the vestry consisted of the wealthy elite living within that parish. Because the vestry hired Anglican ministers on short term contracts, few ministers gained enough power to become independent of vestry control. If sermons within worship services or other activities of the minister were not sufficiently aligned with the perspectives of the local gentry, the minister's contract was not renewed. With a few exceptions, Puritan ministers were pushed out of Virginia quickly.

In the colonial period, the Anglican church had a key role in what today would be considered fundamental government services. The vestry set the parish tax rates for maintaining the church buildings, paying the minister, and funding social welfare expenses such as caring for orphans, the indigent, and others unable to support themselves. Parish taxes were collected by the county sheriffs, along with the other taxes imposed by the county courts (equivalent to a combination of today's Board of County Supervisors and District judges).

The chancellor of the one college in the colony, William and Mary, was always the Bishop of London or the Archbishop of Canterbury during the colonial period. Many of the professors were trained as Anglican ministers. Dissenters were obliged to pay taxes that supported teaching Anglican doctrine at the College of William and Mary.

There was no separation of church and state in colonial Virginia. Everyone, no matter what their personal beliefs, was required to pay taxes that funded Anglican activities. An established church existed in all but the Pennsylvania and Rhode Island colonies. There also was no acceptance within the Virginia gentry of non-Anglican beliefs in the 1600's. Throughout the colonial period, only one Catholic family gained wealth and power, the Brents in Westmoreland and (after 1664) Stafford County. George Brent and his family had to worship privately. The county court in Stafford sought to increase acceptance of the Brents by issuing a certificate in 1668 stating that the Brent family had not tried to convert anyone to their Catholic faith for the last two decades.6

After George Brent had been elected to serve in the House of Burgesses, King James II was forced to leave England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. In 1689, the Anglican minister of Overwharton Parish in Stafford County, Parson John Waugh, inflamed suspicion of the local Catholic leader. During the "tumult" created by his agitation, the Stafford County Court ordered the Brent family to stay at the home of a prominent local Protestant, William Fitzhugh, in a form of house arrest.7

Protestant and Catholic rivalries dated back a century to the reign of Henry VIII. He split from the church based on Rome in order to legitimize his first divorce, and declared that the King of England rather than the Pope was the top authority for religious decisions in England. Claiming that the national religion was based on the sovereign ruler's religion led to conflict when Henry VIII's daughter Mary assumed the throne in 1553. She was Catholic, and married the Catholic son of the king of Spain.

Queen Mary had religious dissenters burned to death. She became know as "Bloody Mary" after graphic accounts and images were published in Foxe's Book of Martyrs. When she died in 1588, Henry VII's second daughter became queen. Elizabeth I was a Protestant, and the definition of heresy changed dramatically as she punished heretics who supported Catholic dogma and the role of the Pope. Catholic Spain tried to invade and conquer Protestant England in 1588, but the Spanish Armada was dispersed in the English Channel. Anti-Catholic bias became closely associated with English nationalism.8

Virginia was settled initially when James I was king, and grew during the reign of his brother Charles I. They were the head of the Church of England, but the forms of worship and the words used during religious services were contested by different factions within the church.

In contrast to Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania were more tolerant of diverse religious beliefs. Even the Pilgrims who arrived in 1620 in Massachusetts recognized the need to accommodate diverse beliefs. The Pilgrims had recruited "strangers" to accompany them to the New World. The Mayflower Compact established how to manage conflict and make decisions within that mixed community.

Maryland had been chartered in 1732 because King Charles I owed favors to the George Calvert, Baron of Baltimore, and his son Cecil Calvert. The Virginians based in Jamestown viewed Maryland as a rival, rather than as an ally in the isolated wilderness of North America. Virginians objected to the loss of land included within the boundaries of Virginia's 1612 charter and the seizure of William Claiborne's lucrative fur trading business based on Kent Island,. Virginians also objected because the Calverts were Catholic, and would fill Maryland with Catholic colonists.

The Virginians had made their dislike of Catholics clear to Sir George Calvert clear in person. When Lord Calvert sailed from his failed colony in Newfoundland to Jamestown in 1629, he was unwilling to take the Oath of Supremacy that Charles I was the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Acting Governor John Pott forced Lord Calvert to sail back to England, where he then proceeded to obtain the charter for a new colony. Calvert named his new colony after Henrietta Maria, the Catholic wife of Charles I.9

Religious disputes between Puritans and the traditional Anglican leaders would lead to civil war in England and the execution of Charles I in 1649. Those conflicts were carried across the Atlantic Ocean to Maryland, which attracted a mix of both English Catholics and English Protestants. In 1649, the Maryland legislature approved the 1649 Maryland Act Concerning Religion, or Maryland Toleration Act which Calvert had prepared.

By then, Catholics were a minority of the population in Maryland. Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had not defined an established church in his colony. The law applied the same punishment to Puritans, Anglicans, Catholics, and others who criticized a Christian faith:10

The Maryland Toleration Act was not sufficient. By 1676, only 25% of the residents in Maryland were Catholics, but they controlled most of the colony's political offices and collected fees from everyone. Colonists in Tidewater feared that the Catholics in the western backcountry might ally with French raiders because of a shared religion.

The Calverts lost control over their proprietary colony in a Protestant-led coup in 1688. That occurred the same year as James II, England's last Catholic ruler, was forced from his throne in the Bloodless Revolution. In 1710, the Church of England became Maryland's established church, and Catholics were excluded from office.11

In Pennsylvania, William Penn managed to encourage religious toleration throughout the life of that colony. He issued a formal Charter of Privileges in 1701. Pennsylvania attracted a diverse set of settlers in addition to immigrants from England, including Swedes, Dutch, Finns, and refugees from many small principalities which would ultimately become part of Germany. Penn's charter gave monotheists the freedom of conscience, and allowed any Christian to hold public office:12

Virginia suppressed Quakers and Puritans as well as Catholics. What may be the first Society of Friends meetinghouse was built at mouth of Nassawaddox Creek in 1657, during the English Civil War. The Eastern Shore was physically isolated from Jamestown, and the extensive international trade brought sailors of different backgrounds to small communities along the Chesapeake Bay.

Virginia officials did not tolerate the Quakers. By 1662, Col. Edmund Scarborough forced those on the Eastern Shore to move north of the Pocomoke River into Maryland. A year later, he led a raid across the border and attacked the Quaker settlements. That triggered a dispute with Lord Calvert in Maryland, followed by a 1668 survey to define the Virginia-Maryland border on the Eastern Shore.

After George Fox came to Virginia in 1672, what is now "the oldest continuous congregation in Virginia" of Quakers started near the Dismal Swamp. That isolated area was a haven for Puritans as well. It was distant from the gentry who created plantation in Tidewater and ruled from Jamestown. South of the James River, tobacco grew poorly. Colonists traded less with England and more with other colonies in North America and with Caribbean islands. Greater business dealings with non-Anglicans led to a less-traditional culture around Suffolk and Norfolk.13

Puritans concentrated there as well. Philip and Richard Bennett came to Warrosquyoake around 1630 and developed Bennett's Welcome plantation. Puritans came to both Maryland and Virginia as conflicts in England grew more heated, and concentrated along the Nansemond River. They sought the freedom for themselves to worship in the Puritan style, but were not advocating that other religious groups have the freedom to worship in their own way.

In 1642, Philip Bennett went to Massachusetts to recruit Puritan ministers to serve in parishes in Isle of Wight, Upper Norfolk/Nansemond, and Lower Norfolk counties. However, Governor William Berkeley came to Virginia in 1642. He was a strong supporter of Charles I, and viewed religious nonconformity as both heresy and political disloyalty.

Under Berkeley, the colonial government in Jamestown began to demand standard use of the Book of Common Prayer in worship services. He forced the three Puritan ministers recruited by Philip Bennett to return to Massachusetts, and later banished other Puritan leaders. Most followers also left, migrating to Maryland by 1650. The 1649 Maryland Act of Toleration offered a clear contrast to Gov. Berkeley's religious intolerance.

In 1652, after Parliament had seized power in England and executed Charles I, Gov. Berkeley was forced to step down. The General Assembly selected Richard Bennett to become the next governor, so between 1652-1655 a Puritan was the top official in Virginia. Bennett sought to impose Puritan control in Maryland as well. That triggered the Battle of the Severn between Catholic royalists and Puritans, while in Virginia there was no open warfare between the Anglican royalists and Puritans because most dissenters had left the colony.14

The Great Awakening began to affect Anglican domination of religious activity in Virginia in the 1740's. Unlicensed preachers began to offer independent services in private homes and scattered outdoor locations. Hierarchical control of culture by the gentry was threatened by evangelical preaching, emotional behavior during worship services, and new philosophies (such as baptizing believers only as adults, after they made a conscious choice). The outreach of dissenting religious leaders to African-American slaves was perceived as a particular challenge to the status quo.15

Colonial officials actively recruited non-Anglican Protestants to come to Virginia. Presbyterians dominated the Shenandoah Valley, after Scotch-Irish migrated to that region with encouragement in the 1720's from Governor Spotswood (who sought a buffer population between Native Americans and French Catholics in the Ohio River valley. Other immigrants west of the Blue Ridge belonged to German sects, including the Mennonites.

In the colonial period, non-Anglican "dissenting" ministers were required to obtain a license to preach from the General Court in Williamsburg, all of whose members belonged to the elite social class and were practicing Anglicans. The 1689 Act of Toleration, adopted after the Glorious Revolution forced James II from the throne and blocked his efforts to reinstall Catholic practices, was applied to Virginia in 1699. The law permitted dissenting faiths, but only tolerated them. The official religious beliefs in the colony were defined by the 39 Articles in the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer.

Methodists and Presbyterian ministers had to swear allegiance to the king or queen when they sought authorization from supporters of a rival denomination. Non-Anglican groups had to worship in authorized "meeting houses" rather than in churches.

The Great Awakening, led by Baptists and "New Light" Presbyterians in particular, threatened Anglican ministers. Within the Anglican faith, John Wesley's Methodist preachings began undermining the traditional authority of Anglican vestries and ministers. Dissenters were more common than Anglicans west of the Blue Ridge prior to the American Revolution, but the more-established Lutherans objected to traveling Moravian preachers that offered a different theological perspective.16

Traditional Anglican services lacked the emotional stimulus provided by dissenters. Most of the major Tidewater landowners objected to the message of the non-Anglican ministers that God valued all souls, and a direct relationship between worshipers and the divine was possible without an intermediary.

Wealthy landowners feared that dissenting preachers would encourage poor farmers and even enslaved workers to adopt independent religious beliefs and practices. Religion could offer an alternative to compliant acceptance that the elite were entitled to power and wealth.

In 1747, Governor Gooch issued a proclamation to limit the capability of itinerant preachers to gather audiences:17

Samuel Davies, who led the Presbyterians in Hanover County, obtained his license to preach as a dissenter from the General Court in Williamsburg. His request may have been viewed favorably in part because his second marriage was to the daughter of the former mayor of Williamsburg.

The Presbyterian meeting house in Williamsburg, established in 1765, was the only non-Anglican place of worship officially authorized in the colonial capital. That application was championed by George Davenport, a clerk in the House of Burgesses who was known by all the rich and powerful men - who worshipped at the Bruton Parish Church.

Baptist groups developed in the Piedmont, plus areas of Tidewater dominated by traditional Anglican churches. In Williamsburg, their public gatherings started in 1776.

In contrast to Anglicans and Catholics, who relied upon many centuries of church tradition to guide the appropriate form of public worship and religious ceremonies, Baptists referred to words in the Bible as the guide. Baptists in the 1700's created no hierarchy of church officials; no one was empowered to determine "correct" behavior other than an person's personal faith and the words in the Bible.

Baptists gathered outdoors rather than withing church buildings. The ministers refused to get licenses from the General Court to preach, denying the government's authority to determine who could lead religious events. Baptists also refused to pay the colonial Virginia tax to support salaries of Anglican ministers, construction of Anglican church buildings, and costs of Anglican vestry operations.

That non-compliance made the Baptists the focus of most official Anglican repression. Anglicans reacted by disrupting Baptist services, plus arresting - and even attacking - dissenting preachers.18