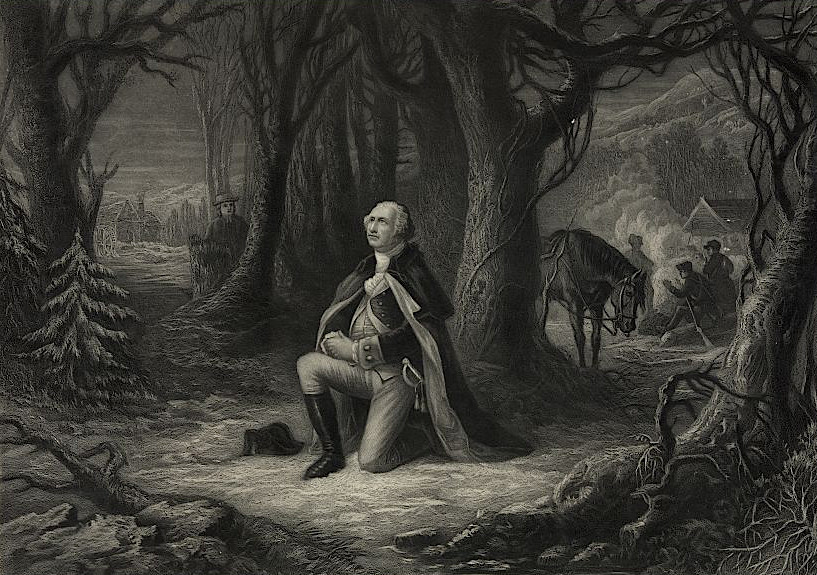

George Washington was a man of faith, while avoiding entangling the practices of government and religion

Source: The prayer at Valley Forge (engraved by John C. McRae, 1866, from painting by H. Brueckner)

George Washington was a man of faith, while avoiding entangling the practices of government and religion

Source: The prayer at Valley Forge (engraved by John C. McRae, 1866, from painting by H. Brueckner)

Washington gives us little in his writings to indicate his personal religious beliefs. As noted by Franklin Steiner in "The Religious Beliefs Of Our Presidents" (1936), Washington commented on sermons only twice. In his writings, he never referred to "Jesus Christ." He attended church rarely, and did not take communion - though Martha did, requiring the family carriage to return back to the church to get her later.

When trying to arrange for workmen in 1784 at Mount Vernon, Washington made clear that he would accept "Mohometans, Jews or Christians of any Sect, or they may be Atheists." Washington wrote Lafayette in 1787, "Being no bigot myself, I am disposed to indulge the professors of Christianity in the church that road to heaven which to them shall seem the most direct, plainest, easiest and least liable to exception."

Clear evidence of his personal theology is lacking, even on his deathbed when he died a "death of civility" without expressions of Christian hope. His failure to document beliefs in conventional dogma, such as a life after death, is a clue that he may not qualify as a conventional Christian. Instead, Washington may be closer to a "warm deist" than a standard Anglican in colonial Virginia.

He was complimentary to all groups and attended Quaker, German Reformed, and Roman Catholic services. In a world where religious differences often led to war, Washington was quite conscious of religious prejudice. However, he joked about it rather than exacerbated it. Washington once noted that he was unlikely to be affected by the German Reformed service he attended, because he did not understand a word of what was spoken.

Washington was an inclusive, "big tent" political leader seeking support from the large numbers of Anglicans, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers in Virginia, and even more groups on a national level. He did not enhance his standing in some areas by advocating support for a particular theology, and certainly did not identify "wedge issues" based on religious differences. Instead, in late 1775, Washington banned the Protestant celebration of the Pope's Day (a traditional mocking of the Catholic leader) by the Continental Army. He deplored the sectarian strife in Ireland, and wished the debate over Patrick Henry's General Assessment bill would "die an easy death."

Washington was not anti-religion. Washington was not uninterested in religion. He was a military commander who struggled to motivate raw troops in the French and Indian War. He recognized that recruiting the militia in the western part of Virginia required accommodating the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Baptists, and Dutch Reformed members in officially-Anglican Virginia. He was aware that religious beliefs were a fundamental part of the lives of his peers and of his soldiers. He knew that a moral basis for the American Revolution and the creation of a new society would motivate Americans to support his initiatives - and he knew that he would receive more support if he avoided discriminating against specific religious beliefs.

In the Revolutionary War, Washington supported troops selecting their own chaplains (such as the Universalist John Murray) while trying to avoid the development of factions within the army. Religion offered him moral leverage to instill discipline, reduce theft, deter desertion, and minimize other rambunctious behaviors that upset local residents. It was logical for Washington to invoke the name of the Divine, but it may have been motivated more by a desire for improving life on earth rather than dealing with life after death.

While never trying to establish an official religion defined by the government, Washington recognized the relationship between religious faith and moral behavior. He said in his 1796 Farewell Address:1

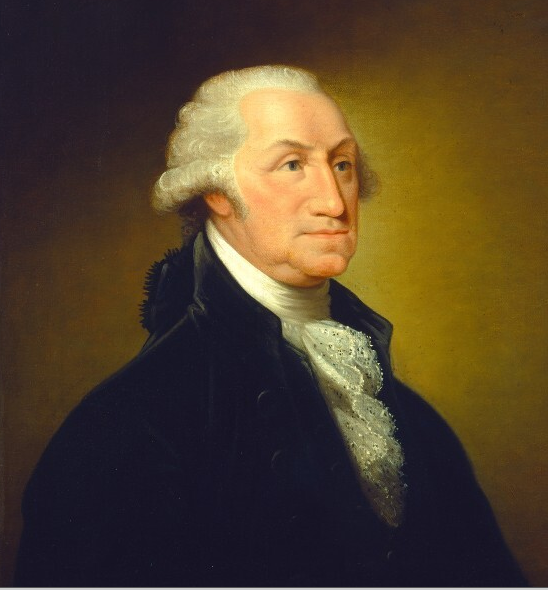

George Washington, at the time he finished his second term as president

Source: National Gallery of Art, George Washington c.1796 (painted by Edward Savage)

George Washington understood the distinction between morality and religion, and between toleration of differences and full religious liberty. His replies to messages from Jews and Swedenborgians showed he was not merely accepting the differences of religion, tolerating those who had not chosen the correct path.

Instead, when in positions of authority he maintained what Jefferson would later define as a "wall of separation between church and state." Though their perspectives on faith and religion varied, neither supported using the power of government to coerce religious behavior or define acceptable/unacceptable theological doctrine.

Washington used generic terms with his public requests for divine assistance, to the extent that his personal denomination must be classified as "unknown." That vagueness has not stopped Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Unitarian Universalists from claiming him as a member, and has invited others to identity him as a Deist.

Washington was a man dedicated to creating national unity, not an exclusionist seeking to identify and select those with correct beliefs for reward in this life or the next. It would have been inconsistent for him to seek to blend the westerners and the Tidewater residents, the Yankees from the north and the slave-owning planters from the South, into one national union - while at the same time supporting narrow religious tests for officeholders, or advocating the superiority of one religious sect over another.

The obelisk we call the Washington Monument is clad in white limestone. When illuminated at night, it glows white. It stands out from the dark background because of the artificial light we project on it; there is no natural light corning from the stone. If we projected a colored light, we'd see the tall Washington Monument as an object glowing with color. Similarly, many writers project onto Washington's life a set of religious beliefs - and see a reflection of what they project.

the original design for the Washington Monument included more ornamentation beyond just the marble shaft

Source: Library of Congress - Chronicling America, Historic American Newspapers, Evening Star (February 21, 1885)

Mason Locke Weems manufactured stories to establish Washington as a pious Christian, a man who suceeded in part because he prayed for God's blessing. Weems was a parson, and his inaccuracies (including the moralistic "I can not tell a lie" tale about cutting down a cherry tree) have shaped the perspective of Washington for two centuries now.

Many modern writers still repeat second-hand information of questionable reliability to describe Washington as a traditional Protestant. The individuals who describe Washington's life as one marked by prayer and steady attendance at church are often advocates of a religious perspective, proselytizing the perspective of a particular denomination or at least trying to shape American society so more people attend church regularly.

At times, they cite the generic proclamations issued as a public leader to portray Washington (or even Jefferson!) as a mainstream Christian, and to define the United States as a Christian Nation. Some of those who emphasize the personal faith - or faithlessness - of elected officials use it as a partisan issue. The Moral Majority led by Rev. Jerry Falwell was clearly allied with the Republican Party, and both Jimmy Carter and Pat Robertson used religion as part of his campaign for the presidency.

In modern America, many religious leaders consider personal salvation to be fundamental to the strength/survival of American society. The debate about the morality of elected officials has been intense since the realization that Lyndon Johnson lied about the status of war in Vietnam and subsequent Presidents have demonstrated publicly their own lapses, particularly Presidents Nixon, Clinton, and Trump.

Those who attempt to project a religious theology upon Washington often seek to connect theological beliefs with civic benefits, assuming morality is based on religion. In contrast, Madison and others crafted a government that could succeed even if Americans were not angels, thanks to a balance of powers. Jefferson and other "natural law" theorists assumed that individuals in a mature society would follow a common set of ethical principles, independent of the different religious beliefs held by individuals.

Washington was a man focused throughout his life on gaining honor and respect. He acted in public settings with some personal distance, even coldness, to reduce the likelihood of some informality reducing the respect he sought from others. So it is likely that he would desire political leaders today to also earn respect through moral, virtuous behavior - even at some personal cost to their comfort level.

However, there is little in Washington's life to suggest he would support a political movement based primarily on a moral agenda. To make such a claim requires that we project a light upon the monument of Washington, then look at our own reflected light and claim its source to be Washington. The "myth of Washington" created during his life and shortly thereafter by Parson Weems is not static. Even today, Washington's life can be re-shaped when necessary to fulfill the agenda of a modern mythmaker.