Ely Mound in Lee County

Source: Wikipedia, Ely Mound

Ely Mound in Lee County

Source: Wikipedia, Ely Mound

The most obvious examples of easily-recognized Native American gravesites are the large earthen mounds constructed west of the Blue Ridge from Southwestern Virginia (including Ely Mound and Carter Robinson Mound in Lee County) through the Shenandoah Valley. There are 13 documented mound complexes in Virginia. Of that number, seven were made from just earth and six were made with a combination of earth and stones.

The Virginia mounds were built originally between 900 CE-1440 CE (Common Era). Because the upper portions of the mounds have been removed, it is not possible to date their last use. They could have been used as recently as the 1700's.

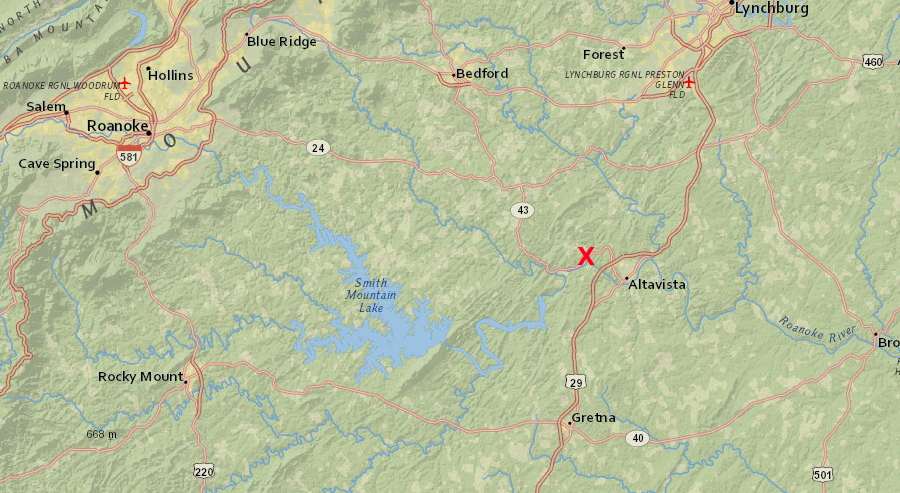

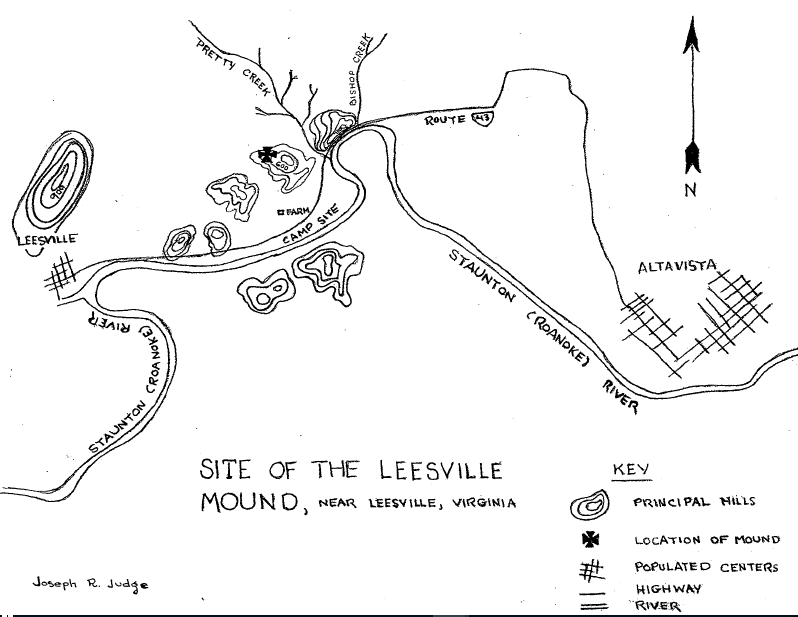

Three were built east of the Blue Ridge. The Rivanna (Jefferson) Mound is in the headwaters of the Rivanna River, and the Rapidan Mound is 14 miles to the north in the headwaters of the Rapidan River. The Leesville Mound is on the Roanoke River near modern Altavista. Further east Native Americans created ossuaries, collecting bones of the dead and stockpiling them in secondary burials.

The Piedmont mounds are thought to be the most recent. They have a lower percentage of bones from infants and juveniles, compared to the mounds west of the Blue Ridge. Cultural practices may have changed over time. In the older mounds, everyone who died with a certain time period may have been placed in a layer of bones and earth added to the mound. In the Piedmont mounds, it appears few infants and juveniles were excavated and reinterred with the adults when a mound was expanded.

It appears that all the mounds were constructed not only as burial sites, but also as ceremonial centers. Postholes indicate structures were associated with the mounds, and presumably used for rituals. At the Rapidan Mound, archeologists found nails in the top layers, indicating that during the colonial period settlers also built structures on top of the mound.1

The mounds in Virginia are associated with the Mississippian culture that developed during the Woodland Period around 1000CE (Common Era), but the practice of building earthworks in North America is much older.

The earliest artificial earthworks in North America were built in Louisiana. Two of the oldest structures on earth are located on the Louisiana State University campus in Baton Rouge. Construction of "Mound B" began about 11,000 years ago (9,000 BCE), near the end of the Paleo-Indian Period. Construction stopped around 8,200 years ago during an abrupt period of cooling climate. About 7,500 years ago, construction began of nearby "Mound A" and restarted at "Mound B." Both were completed around 6,000 years ago (4,000 BCE).

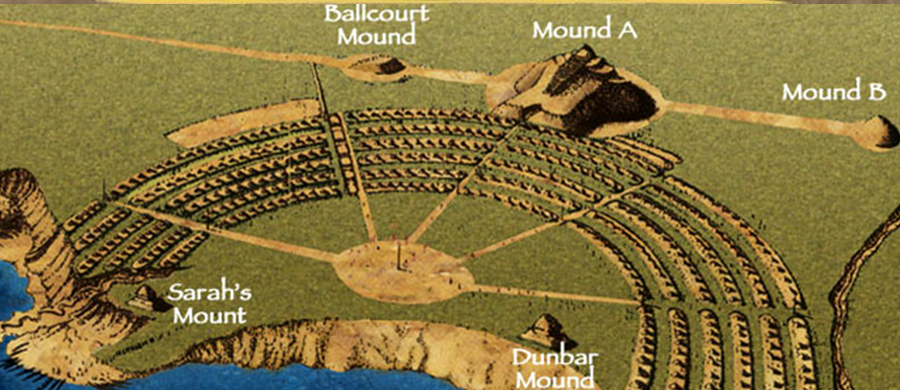

Other mounds also were built in what is now Louisiana during the Archaic Period. Over decades or even centuries, visitors to Watson Brake (3,400 BCE), Poverty Point (1,600 BCE), and other early mounds built several thousands of years ago gradually expanded the structures, hauling baskets of dirt to build crescents of raised land.

The motivation to build the mounds is not known, but they may have been created to provide an elevated platform at regular gatherings for trade and intermarriage. Archeologists have recovered ash and bone fragments, indicating the mounds were used for ceremonial purposes but not burials.

the oldest known human-made structures in North America are on the grounds of Louisiana State University

Source: Louisiana State University, New Research Shows LSU Campus Mounds As The Oldest Known Man-Made Structures In North America

The ancient mounds in Louisiana were constructed before the development of agriculture. The particular Louisiana sites may have been chosen because wetlands nearby could feed a large hunting/gathering group during brief visits. Construction may have involved just several days of labor each season, in a time before permanent towns were established, within a society that could organize large construction projects. There is no evidence of long-term dwellings at Poverty Point, suggesting that there was no organized paramount chiefdom which forced laborers to move enough dirt 3,500 years ago to fill 140,000 modern dump trucks.

Watson Brake and Poverty Point were not built on a random whim. The investment of labor to pile up the dirt demonstrates that the mounds had some sort of meaning, but archeological investigations have not shown a clear association with burials.

The first mounds may have been started initially to mark the location of sites where festivals could be held, since the area provided enough food for a temporary gathering. Location of the initial mounds may have been determined by something not obvious today. Perhaps one influential leader had a vision at Watson Brake or Poverty Point, and was able to organize enough followers to identify a spiritual center by raising a mound. The initial structure might have been produced in just several days by a few dozen people, then expanded gradually in continual short visits.

One researcher at Poverty Point has noted:2

Poverty Point earthworks were engineered so well that they have resisted 3,600 years of erosion

Source: Wikipedia, Poverty Point

Complex societies developed around 1,000CE in the Ohio River and Mississippi River valleys, after adoption of corn expanded the food supply and population increased. Egalitarian hunting/gathering bands were replaced by stratified, sedentary societies. Most mounds appear to have been built after adoption of agriculture, which provided a reliable supply of food for the workers who piled up the dirt.

When Native American bands relied upon hunting and gathering, leaders of a hunt and decisionmakers on where to gather food probably were chosen based on merit. Those men and women who had demonstrated success in previous food gathering directed the next effort. Short lifespans required regular changes in leadership, and constant movement to collect food limited the ability to acquire bulky prestige goods.

When Native American societies began to rely upon agriculture and establish permanent settlements, the pattern changed. An increase in the food supply led to an increase of inequality. In the Mississippian Period, elite spiritual, political, and military leaders acquired special status. Economic wealth and authority were concentrated within the leadership, creating stratified societies with a "1%" category. Somehow, perhaps by articulating spiritual beliefs and manipulating religious practices, the elite were able to get a large number of workers to carry baskets of dirt and construct mounds as much as 100' high.

Earthen mounds were built by accretion, through hard work without labor-saving animals or equipment. The first component was often a structure with wooden posts, and sometimes with slabs of stone. Elite leaders were buried within the structure, then dirt was piled on top and on the sides. On top of the platform, new structures served as meeting places.

The mound construction process used the same technology and techniques for 5,000 years, from creation of the original mounds in Louisiana to the final mounds built around 1700 CE. The construction of the mounds, as described by one anthropologist, required no sophisticated tools:3

earthworks at Poverty Point included six rows of concentric ridges, some five feet high

Source: Louisiana Public Broadcasting, Poverty Point Earthworks: Evolutionary Milestones of the Americas

After initial construction of a low mound, people often were buried on the sides and a new layer of earth added to expand the width of a mound. The structures on top could be burned in a ritual ceremony, or repurposed as another tomb covered with dirt, to increase the height with new layer of earths carried to the top of the old mound.

There is no historical documentation of the Mississippian culture and the people who build the mounds. What we know today is discerned through archeological investigation. When colonists first entered the Ohio River and Mississippi River valleys, the Native Americans were using mounds that had been completed by earlier cultures.

Structures on the top are thought to have included housing for the elite, meeting places and feast sites for larger groups, sweat lodges for ritual cleansings, and temples for bones of the dead. Enlarging a mound added space for more burials, and the increased size made the site more impressive.

Leesville Mound is downstream of Smith Mountain Gap, a clearly-recognizable landscape feature

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Mounds were started where there was already bodies, typically buried in a pit. Burials in a Virginia mound were not a one-time event; they continued for centuries. Some were primary, but others were secondary burials where bones were dug up from another site and transferred and reburied in the mound with some sort of ritual. In the earth-stone mounds, rocks were placed on top of the burials.

Adding the dead to an existing mound and building a new set of structures on a larger platform, rather than building a new mound, affirmed continuity with the past. Power and authority associated with the dead was transferred to the next generation, using the expanded mound as part of an ancestor cult. In some cases, such as Mound 72 at Cahokia (Illinois), people were sacrificed and buried in mounds.

Burials did not occur in random one-time events, as people died. Instead, burials and mound expansion occurred in cycles, probably as an event involving a population of over 300 people living in separate towns. Bones of multiple individuals who had been buried elsewhere were gathered from one or more other locations and interred as a group, perhaps annually or once every three years. A ritual:4

Mounds built on natural high spots in the local topography provided a rare opportunity to see great distances, even over the tops of trees. Perhaps equally important, the mounds could be seen from long distances, and may have marked boundaries or the center of territory controlled by a particular set of families that evolved into clan and tribal leaders.

One mound complex is on the South Branch of the Shenandoah River, where the highly-valued jasper and flint were excavated for over 10,000 years at the Thunderbird site. The nomination form for the National Register of Historic Places notes:5

Mounds may have been associated with kin groups, and people buried in a mound may have been related to each other. As different kin groups established greater authority and became the source of chiefs in different tribes, mound burial may have become a "perk" restricted to the families of the powerful.

The distinctive mounds became the most obvious Native American gravesites in Virginia. People were also buried away from the mound, but archeological research and preservation efforts focus on the obvious structures. There may be far more individual burials, away from the mounds, than the few Native American skeletons found so far. Assuming Virginia was occupied for roughly 15,000 years before colonization, there are many unidentified burial sites. Modern development - houses, roads, shopping centers near floodplains that were once Native American corn fields - has occurred on top of many unidentified Native American gravesites.6

Trade and migration along the Kanawha and Tennessee rivers brought the Mississippian culture into Southwest Virginia. Immigrants with a different culture, and perhaps a different language, walked from the Norris Basin in Tennessee up the Powell River to Indian Creek in what is now Lee County. Some may have come through Cumberland Gap. The migrants grew no corn, so their base may have been primarily a trading station for shells and salt.

The new arrivals may have constructed Ely Mound first, then moved about 6 miles south. We know immigrants associated with Mississippian culture had arrived between 1250 to 1400CE, because they built what is known now as the Carter Robinson Mound (44LE10) in the Powell River watershed.

The Carter Robinson Mound was constructed in two-three major episodes early in the occupation of the site. The site was occupied for a century, during which the occupants adopted some of the Radford pottery style (with limestone temper) used by the neighbors. Of the four structures identified by archeologists, one showed evidence of shell bead crafting but lacked evidence of domestic occupation. It may have been the center of trading activity.

The trading station evolved into a production center where cannel coal was carved into artifacts for exchange. Later, trading connections with Saltville included creation of kinship relationships through exchange of women. That enabled those living at Carter Robinson to start salt production for trade.

Saline waters were boiled in pottery bowls shaped for that purpose, evaporating the liquid so salt crystals could be scraped from the pan. The salt was exchanged for shells from the Atlantic Coast, which were carved into gorgets and traded further inland. Women may have been in charge of the trading network, which layer shifted from Saltville to Western Carolina Pisgah groups.7

">

archeologists excavating at Carter Robinson Mound in Lee County, near Cumberland Gap

Source: Facebook, Carter Robinson Mound Site

Similar immigrants with a key common cultural characteristic (construction of burial mounds) arrived further north in Virginia, or perhaps local residents changed their habits and adopted elements of the Mississippian culture. Multiple mounds were constructed on floodplains within the Seven Bends of the Shenandoah River, but have been flattened by farming since the 1700's.

West of the Blue Ridge in the watersheds of the James and Shenandoah rivers, mounds as high as 20 feet contained many more human remains than mounds in the Tennessee River Valley. In Virginia places occupied by the Earthen Mound Burial Culture after 950CE:8

The Mississippian culture thrived in the Ohio River Valley until around 1400CE. The mounds in Virginia may have been constructed a century before Columbus "discovered" America. The people who built the mounds then morphed into new cultures, the tribes of the historical period encountered by early explorers and settlers in western Virginia in the 1600's and 1700's. Those new tribes could have continued to expand or at least venerate the mounds into the time of the American Revolution.

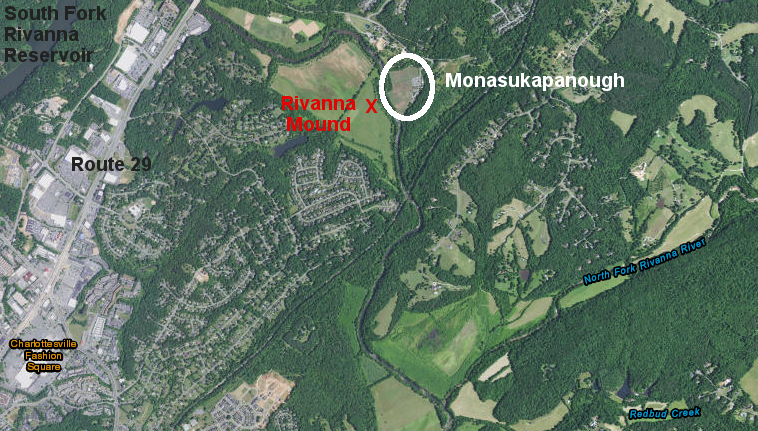

Radiocarbon dates show that the 13 burial mounds in Virginia were started between 900 CE-1440 CE. Burials may have been added to some mounds into the mid-1600's, and their presence was remembered even after burials stopped. Thomas Jefferson reported that as a child, he saw a group of Native Americans go six miles out of their way to visit a mound near Charlottesville on the Rivanna River. He also identified the location of one near modern-day Waynesboro:9

Jefferson recognized that the most obvious reminder of the original inhabitants of Virginia were those mounds:10

A curious Thomas Jefferson conducted the first American scientific archaeological study of a Monacan mound on the Rivanna River. That excavation established his reputation today as the father of American archeology. As one scholar noted:11

Jefferson's report of the mound included:12

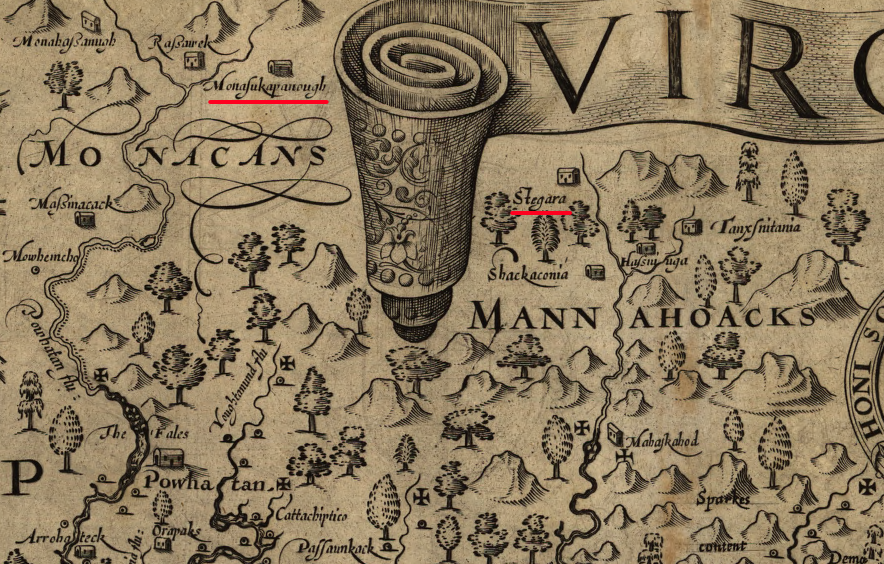

Monasukapanough, the main Monacan town, was located across the South Fork of the Rivanna River from the mound that Thomas Jefferson excavated (exact location of the mound is unknown)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

He discovered that the bones were placed at different layers in the mound, proving it was built in stages. Bones were not the remains of intact bodies buried in the mound. Instead, they had been brought to the mound after flesh had been removed or decayed away. Some skulls had been used as containers to hold small bones.

Jefferson estimated that the Rivanna Mound included the remains of 1,000 people. He recognized with insight that he did not find smashed skulls and broken bones of warriors killed in battle. He concluded from the absence of trauma on the bones that the mound was not a battlefield cemetery, but instead was the "common sepulchre of a town."13

Jefferson also reported that there was a mound north of Woods Gap in the Blue Ridge that was:14

in addition to mounds that were removed for farming or construction, others were destroyed by people seeking artifacts rather than information

Source: Judith H. Dobrzynski, A Wider View of Grandeur: Restoring an American Treasure

The earth mounds were disturbed by early settlers, and most were flattened for farming. Jefferson also commented regarding two mounds near his home:15

In 1911, David I. Bushnell, Jr. excavated the site on the Rivanna River. He reported that the mound, known locally as "The Indian Grave," had entirely disappeared by then. Repeated plowing at the site had helped to flatten it, but a major flood 40 years earlier had eroded the top two feet. He found no skeleton parts, and no other evidence of burials. He did record local lore that in the 1700's Native American groups visited not only the Rivanna Mound, but also two other mounds across the Blue Ridge in the Shenandoah Valley.16

The Leesville Mound was largely destroyed by young boys excavating soapstone pipes and other artifacts to sell to a collector. When the collector realized what was happening, he conducted his own dig and found human remains:17

Leesville Mound had five burial layers

Source: Archeological Society of Virginia Quarterly Bulletin, The Leesville Mound (December 1952, Figure 1)

The Rapidan Mound was once 15 feet high. John Smith recorded the town of Stegara on his map, where the mound was located. By the end of the 1800's, half of the mound had been eroded away by the Rapidan River, the center had been quarried, earth had been removed to enrich nearby fields, and layers of bone had been disturbed by looters. Today, the small remaining portion of Rapidan Mound is just six feet high.

Scientific excavation by University of Virginia archeologists in 1988-1990 removed human skeletal remains associated with at least 60 individuals. Archeologists mapped both "bone beds" of secondary reburials within the mound and pit burials below the base of the mound. The 9,000 bones were reburied by the Monacan tribe in 1998.

The archeologists estimated that remains of 1,000-2,000 people had been buried over time in the Rapidan Mound, making it the largest Native American burial site in Virginia. The presence of just one mound in the Rapidan watershed and one mound in the James River watershed suggests they defined the territory of the Manahoac and Monacan nations. The Leesville Mound on the Roanoke River may identify territory of the Totero or another Siouan-speaking group.18

the Rapidan Mound was constructed next to the town of Stegara in territory of the Manahoack, and the Rivannna (Jefferson) Mound was at Monasukapanough in Monacan territory

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

A mound in Loudoun County, at the corner of Route 15 and Foxfield Lane south of Leesburg, has been reported to be a burial site. It is located on the grounds of what was once the Greenway farm, which developed after a land grant from Lord Fairfax in the 1700's.

According to local lore, Catawba warriors ambushed a band of Delaware (Lenape) near the Potomac River, or perhaps near the confluence of Goose Creek and Little River. The Delaware were returning from a raid into the Carolina Piedmont when the Catawba surprised them and killed many. The bodies were supposedly buried in a mound, and Native Americans continued to visit the site until recently.

The Monacan clearly build burial mounds near modern-day Charlotteville. Native Americans in the Piedmont also built mounds as war memorials. John Lederer, who reached the top of the Blue Ridge in 1669, reported:19

It is reasonable to assume a fight could occur near Leesburg among rival tribes. The path at the base of the Blue Ridge, roughly Route 15 today, was used for raids in the 1600's by both southern and northern tribes until the Iroquois signed away their right to use it in 1722 Treaty of Albany.

However, it is highly unlikely that the mound is associated with the Mississippian moundbuilding culture. It is also unlikely that a raiding party of Delaware in the 1700's would have created a mound for a burial site. Piling up dead bodies above the surface and adding dirt to create a visible mound is not a Delaware tradition. The one report of Delaware buried in a mound, written a century ago, probably reflects the topography of a burial on a hillside.20

a supposed burial mound of Delawares is in Loudoun County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

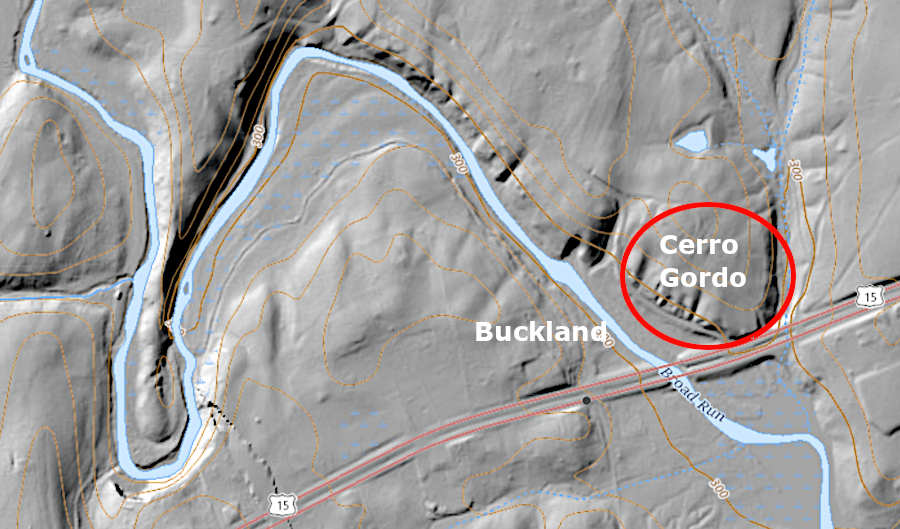

Another site in western Prince William County, the hill east of Buckland known as Cerro Gordo, is also reported by oral tradition to be a Cherokee dancing ground or "step mound." That tradition is based upon a 2009 phone interview with Chief Eagle, who was living in Canada and was 84 years old at the time. He had visited the site in 1955 to establish the claim that the Cherokee had lived far beyond western North Carolina before removal in 1817-1839.

An existing mound at Cerro Gordo, dating back as much as 4,000 years, was supposedly adopted for use by the Cherokee for dancing and cleansing water ceremonies.

Chief Eagle said he was led by local residents with Native American ancestry to three round depressions, four-five feet deep, which may have been the sites of earth lodges. Those local residents reported that other smaller mounds were once located nearby. Two were located when Chief Eagle visited in 1955, but perhaps 20 others had disappeared by that time. There is speculation that the smaller mounds were used for burials, but no archeological sites have been identified in Prince William County with Native American burials.

A modern story about the 2009 phone call says:21

Cerro Gordo, a hill in western Prince William County, has been reported to be the site of a "step mound" used by the Cherokee for dancing

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

It is likely that the Cherokee visited the site of Buckland often in the 1600's. They would have traveled north along a well-used trail on the eastern edge of the Blue Ridge, together with the Catawba from the Piedmont of what is now North Carolina, to trade with northern tribes and especially to raid the Iroquois. Their raiding expeditions, and return trips by the Iroquois to attack the southern tribes, displaced the Manahoacs who John Smith had reported were living in the area when he visited the mouth of the Occoquan River in 1608.

Step mounds were used by the Cherokee for dancing during the Green Corn Ceremony. Most Cherokee raids against the Iroquois occurred in the Fall, after the harvest of corn was completed and the brush had died back to clear the trails. Perhaps the natural hill at Cerro Gordo was used as a "step mound" for a ceremonial dance not associated with the Green Corn Ceremony, or perhaps a Cherokee raid left so early in summer that the first harvest of green corn was being celebrated.

Either way, it is highly unlikely that a new mound would have been created by the Cherokee at Cerro Gordo between the late 1600's and the 1722 Treaty of Albany, in which the Iroquois abandoned their right to travel along the eastern edge of the Blue Ridge. If the Manahoacs, or earlier residents who shared the Moundbuilder tradition, had left behind an ancient mound of some sort, the only evidence today is the memory of a 1955 site visit documented in a 2009 telephone conversation.

Multiple reports of Native American mounds on Virginia's Coastal Plain have been investigated by archeologists. In no case has a mound been authenticated as a prehistoric or even historic site used by Native Americans for ceremonies or burials. Historical records from the early colonial period do not include references of Algonquian-speaking tribal groups on the Coastal Plain constructing any temples on top of raised platforms.

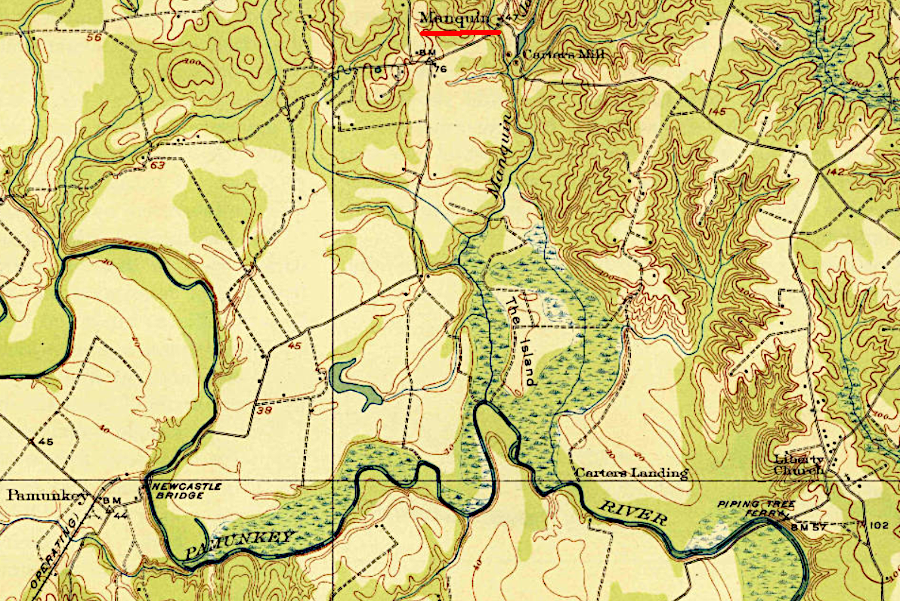

Coastal Plain mounds have been identified as either natural erosional features or associated with construction projects. A mound on the Pamunkey Reservation, reportedly the burial site of Powhatan or Opechancanough, is more likely the residue from completion of the Richmond and York River Railroad in 1861.

Two possible burial mounds near Manquin in King William County were investigated in 1983. One mound was 75 feet in diameter and 10 feet in height; the other was roughly 100 feet in diameter and 15 feet in height. Human bones apparently were found 40 years earlier at the larger mound, and they were nar Opechancanough's settlement of Menmend.

Flakes from manufacturing stone tools were found on both mounds, but the two mounds turned out to be natural features. The lithic residue was probably created when Native Americans hunting in the bottomlands of the Pamunkey River stopped on the mounds and sharpened their stone tools.22

two reported burial mounds near Manquin turned out to be natural erosional features

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), King William VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1920)

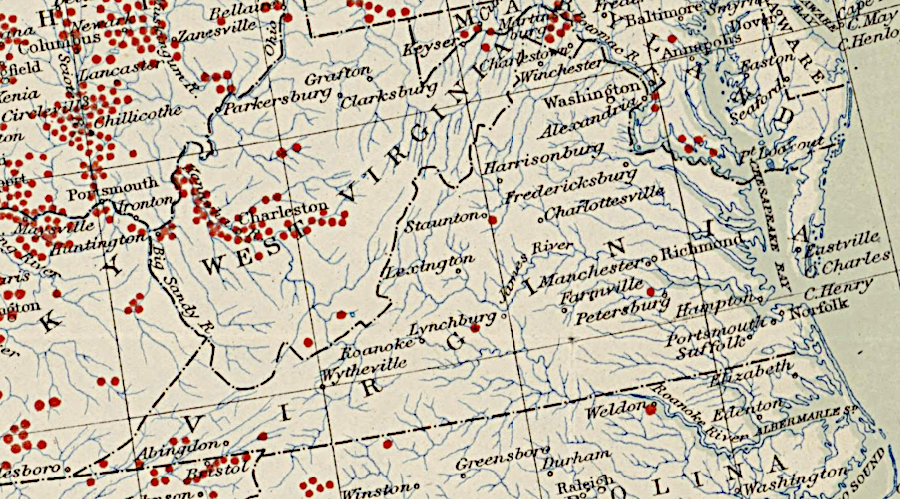

in an 1894 map, the Smithsonian identified what it considered to be Native American mounds east of the Rocky Mountains

Source: Library of Congress, Distribution of mounds in the eastern United States (compiled by Thomas Cyrus, 1894)

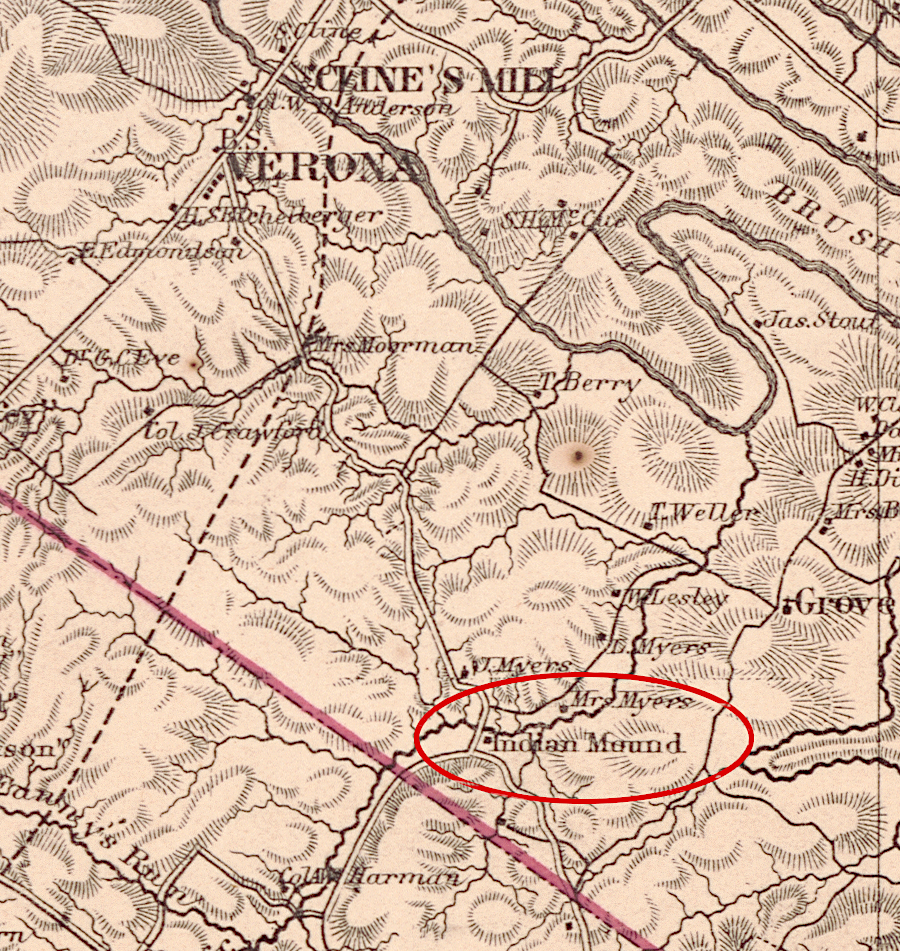

one of the burial mounds in the Shenandoah Valley is remembered today by Indian Mound Road, crossing Lewis Creek in Augusta County

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Augusta County, Virginia (Jedediah Hotchkiss, 1870)