Burial Caves in Virginia

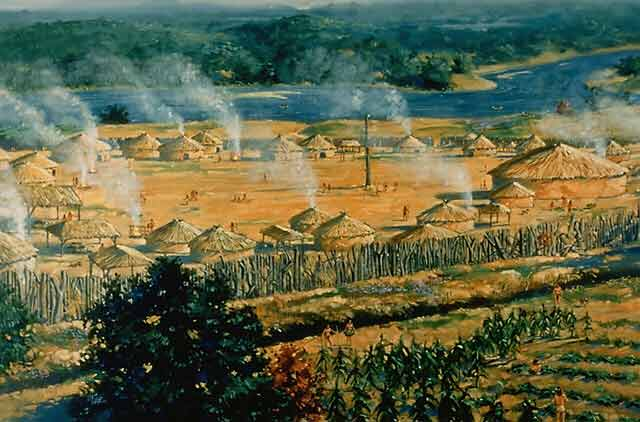

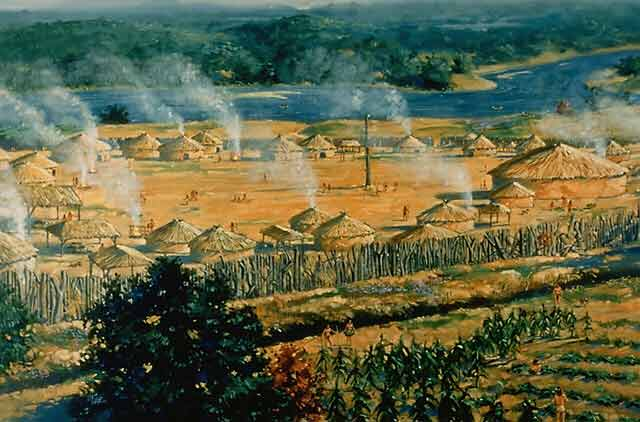

the practice of burying cave burials, along with ceremonial earthwork complexes, were a part of the Mississippian culture brought into Southwestern Virginia from Alabama and Tennessee

Source: National Park Service - Southeast Archeological Center, Mississippian and Late Prehistoric Period

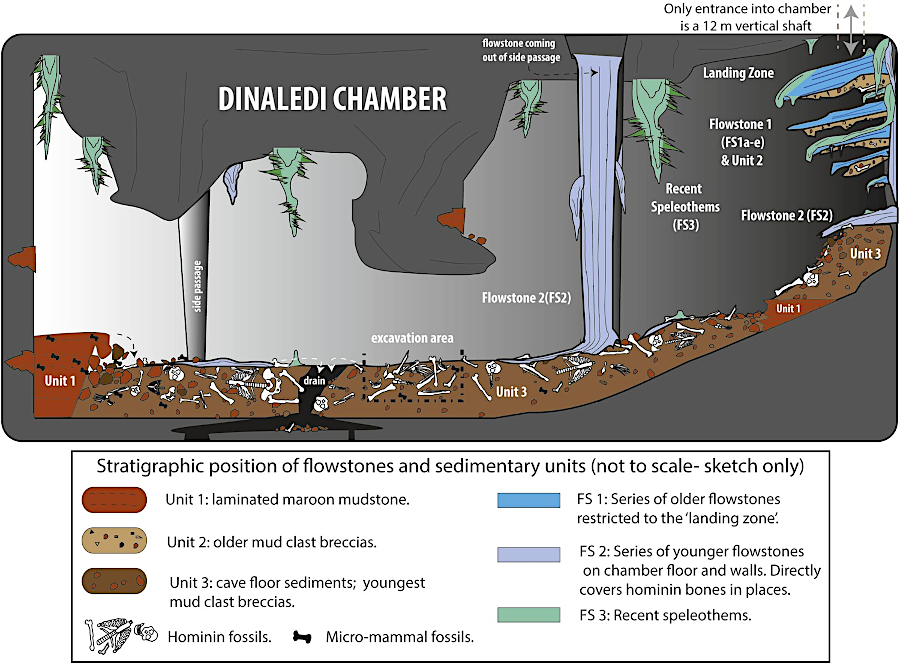

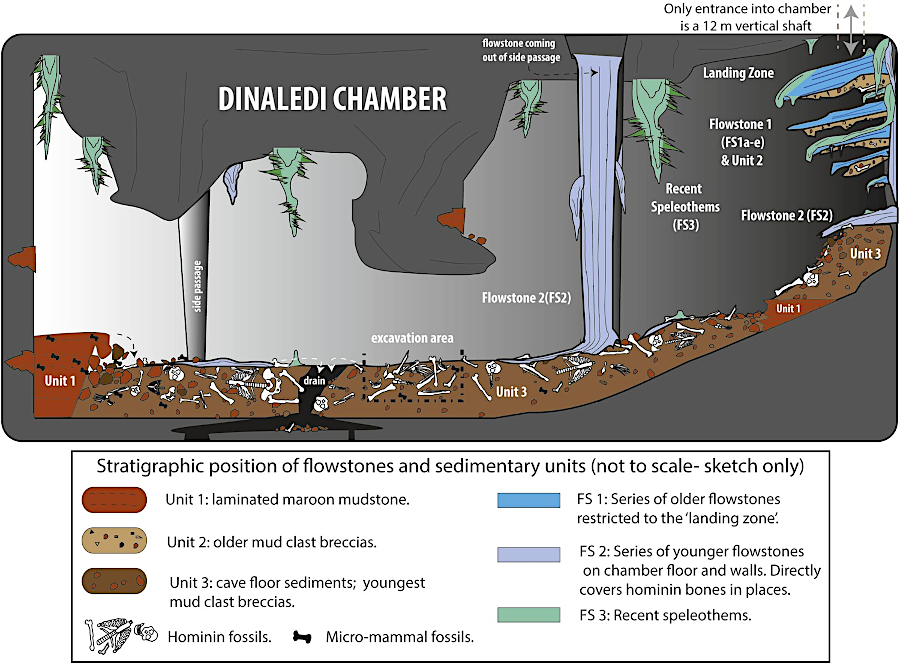

The oldest burial site in the world may be 15 individuals within Rising Star Cave in South Africa, in the Dinaledi Chamber 100 yards from the cave entrance. Engravings on the wall may have been part of a ceremonial marking of the site by members of the Homo naledi species between 236,000-335,000 years ago.

Other archeologists think that Rising Star Cave was a natural death trap, or where water transported a body. The oldest known intentional burial of any members of the Homo sapiens species is at Qafzeh Cave in Israel, dating back 120,000-90,000 years ago.1

the oldest known intentional burial, if confirmed, would have occurred 236,000-335,000 years ago in Rising Star Cave in South Africa

Source: e-Life, Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa

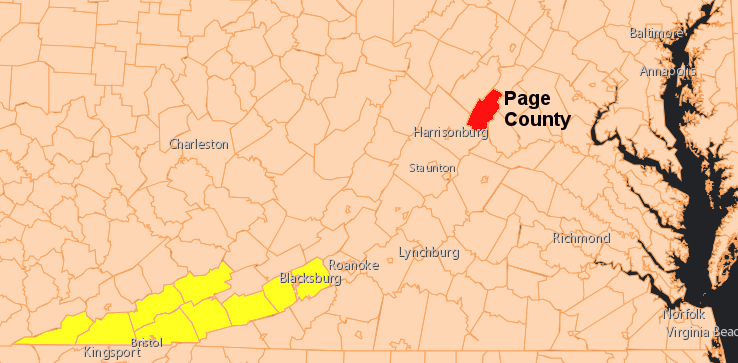

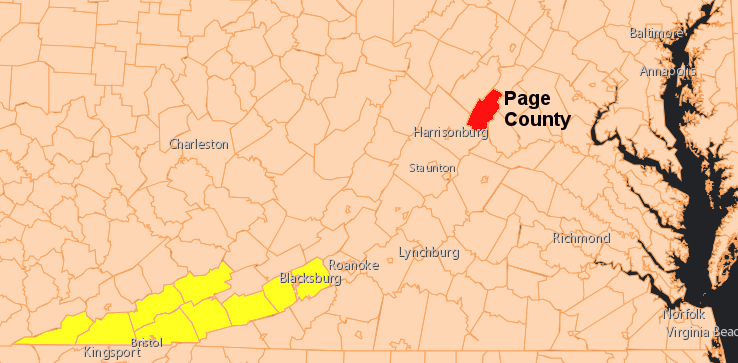

Over 50 mortuary caves in Virginia have been identified between the Tennessee border and Montgomery County. In addition, one mortuary cave in Page County with remains of five people, including a pregnant woman with a fetus, was documented by archeologists in 1939-40. The distance between that cave and the Southwest Virginia burial caves requires a 150-200 mile walk.2

In the calcium-rich caves in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, bones have survived even though modern visitors and vandals have disturbed almost every cave burial site. If there were cave burials in Virginia prior to the Woodland Period, they have not been discovered.

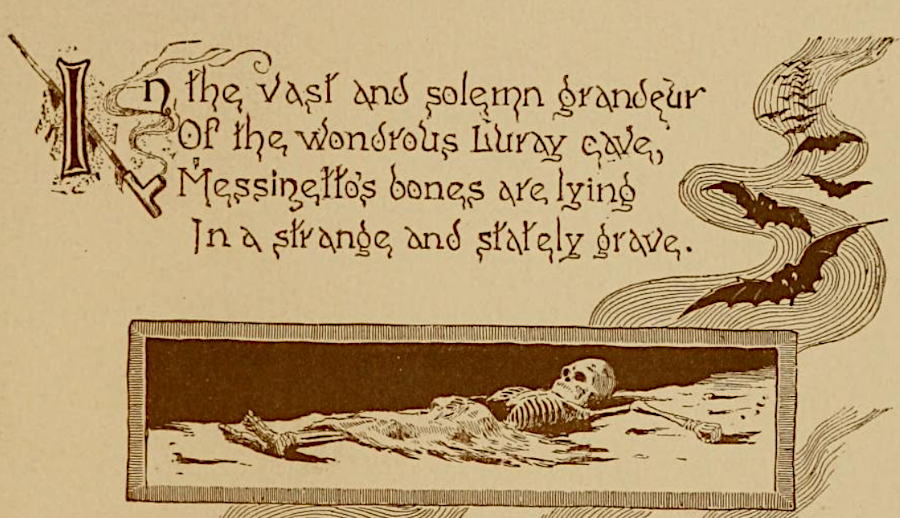

Bone fragments discovered within a stalagmite in Luray Caverns is estimated to have been inside the cave for 500 years, based on the speed at which the calcite accumulated around the bones. a burial may have dropped down from the surface through a sinkhole rather than been placed intentionally in the cave. Tourists still walk through "Skeleton Gorge" when visiting the caverns, but the stalagmite with the bone fragments was sent to the Smithsonian Institution in 1920.

discovery of bone fragments at Luray Caverns spurred the imagination of writers

Source: Pauline Carrington Rust, Legend of the Luray caverns, founded upon the discovery of a skelton in one of its chasms

During the Mississippian Period (800-1600CE), Native Americans living in the Southeast from Alabama to Tennessee buried some people in caves as well as in ceremonial mounds. Migration of people, or cultural diffusion through trade and marriage, carried the cave burial practice across the watershed divide from the Tennessee River to the New River:3

- In the far southwest corner of Virginia, these natural burial chambers likely relate directly to the Dallas culture and people, who entered the area during

Mississippian times. To the east, however, the cave interments of Smyth and Washington appear to be under Mississippian influence but not of Mississippian culture. In this area, cultural complexity may also have been at the chiefdom level with differential distribution of wealth items.

mortuary caves in nine Southwest Virginia counties, from Montgomery County to Lee County, indicate the Mississippian Period culture included the Tennessee and New River valleys

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

there is a burial cave in Page County, far from those in Southwest Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

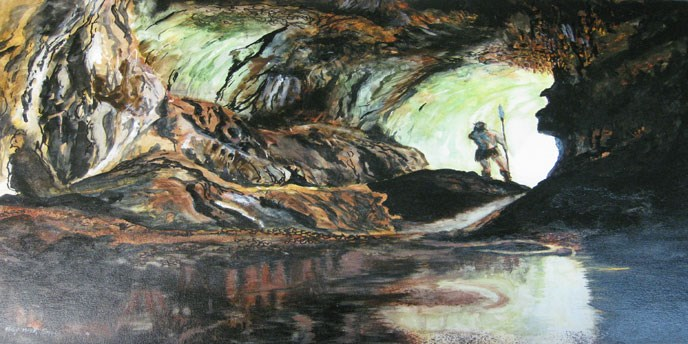

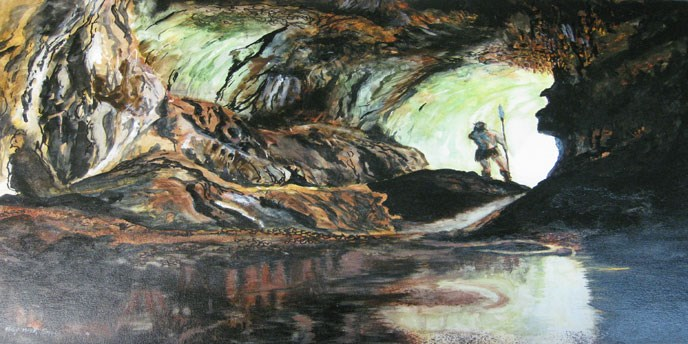

Native Americans moved beyond the twilight zone into the dark regions of caves to deposit human remains

Source: National Park Service, Russell Cave National Monument

The Marginella Burial Cave Project started in 1992. Its researchers have worked with law enforcement personnel, cavers, landowners, and state agencies to protect caves and minimize disturbance of underground archeological resources. Scientific exploration is constrained by modern sensitivities and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NGPRA), but remains from approximately 400 people have been identified from caves in Southwest Virginia. Farley's Cave in Lee County, Elk Garden Cave in Russell County, and Higgenbothan Cave in Tazewell County each may have included the remains of 100 or more people.

Natural holes in the ground could have been viewed as portals for passage on the journey to whatever afterlife was envisioned. Some human remains were found in the "twilight" area of a cave near the entrance, while in other cases the remains had been carried into the "dark" zone requiring artificial light such as burning sticks or reeds. At least one burial was placed on a ledge 15 feet above the cave floor, suggesting ladders were brought into the cave for final placement.

Cremation before deposition of remains in caves was apparently rare, based on the small number of burned human bones fragments found so far. There is a mix of bones from adult males and females, and from children. That, along with the absence of trauma marks, suggests that warriors were not singled out for cave burial as a particular honor.4

It is possible that placing the remains in a cave may have been used by some small villages without a burial mound, perhaps as a rare form of burial for certain kinship groups. There is not enough evidence, especially after disturbance of remains by relic hunters and vandals, to determine if the graves reflect burials of people with inherited (ascribed) status, or of individuals who had achieved status.

If a site includes prestige goods associated with men, women, and children of all age groups, then it could be interpreted as the family grave of a hereditary chief. All members of such a family would have ascribed status due to their kinship status, even the children. If prestige goods are associated with young men or mature adults, without any skeletons of children, then the gravesite may be the final resting place of just those individuals who had accomplished something special in warfare or in the life of a community.5

The social status of people buried in limestone caves in Virginia is not clear. No identifiable artifacts were found that associated Virginia's mortuary caves with just the elites or with any particular clan. There is not a clear enough pattern to state whether the caves are sites of those with inherited, or with achieved, status.

Links

- Virginia Department of Historic Resources

References

1. "Rising Star," National Geographic Society, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/society/projects/rising-star/; Paul HGM Dirks et al., "The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa," eLife, Volume 6, 2027, https://www.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24231; María Martinon-Torres, Diego Garate, Andy I.R. Herries, Michael D. Petraglia, "No scientific evidence that Homo naledi buried their dead and produced rock art," Journal of Human Evolution, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103464; Bernard Vandermeersch, Ofer Bar-Yosef, "The Paleolithic Burials at Qafzeh Cave, Israel," Paleo, Volume 30, Issue 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.4000/paleo.4848 (last checked February 27, 2024)

2. C. Clifford Boyd, Jr., Donna C. Boyd, Michael B. Barber, David A. Hubbard, Jr., Michael R. Barber, "Southwest Virginia's Burial Caves: Skeletal Biology, Mortuary Behavior, and Legal Issues," Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Fall, 2001), p.223, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20708160; Carl Hanson, Howard MacCord, "A Shenandoah Valley Burial Cave," Quarterly Bulletin, Archeological Society of Virginia, Volume 6, Number 4 (June 1952); Michael B. Barber, David A. Hubbard, Jr., "Overview Of The Human Use Of Caves In Virginia: A 10,500 Year History," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), p.134, https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Barber.htm (last checked August 5, 2017)

3. Michael B. Barber, David A. Hubbard, Jr., "Overview Of The Human Use Of Caves In Virginia: A 10,500 Year History," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), p.134, https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Barber.htm; "Luray Caverns," Place and See, https://placeandsee.com/wiki/luray-caverns; American Anthropologist, American Anthropological Association, Volume 23 (1920), p.391, https://www.google.com/books/edition/American_Anthropologist/ALwRAAAAYAAJ (last checked January 21, 2022)

4. David A. Hubbard, Jr., Michael B. Barber, "Virginia Burial Caves: An Inventory of a Desecrated Resource," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), pp.153-154, p.158, https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Hubbard.htm; C. Clifford Boyd, Jr., Donna C. Boyd, "Osteological Comparison of Prehistoric Native Americans From Southwest Virginia and East Tennessee Mortuary Caves," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), p.165 https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Boyd.htm (last checked August 1, 2017)

5. Christopher B. Rodning, David G. Moore, "South Appalachian and Protohistoric Mortuary Practices in Southwestern North Carolina," Southeastern Archeology, Volume 29, Number 1 (Summer 2010), http://www.tulane.edu/~crodning/rodningmoore2010.pdf (last checked August 7, 2017)

Population of Virginia

"Indians" of Virginia - The Real First Families of Virginia

Virginia Places