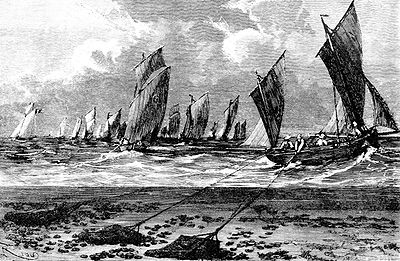

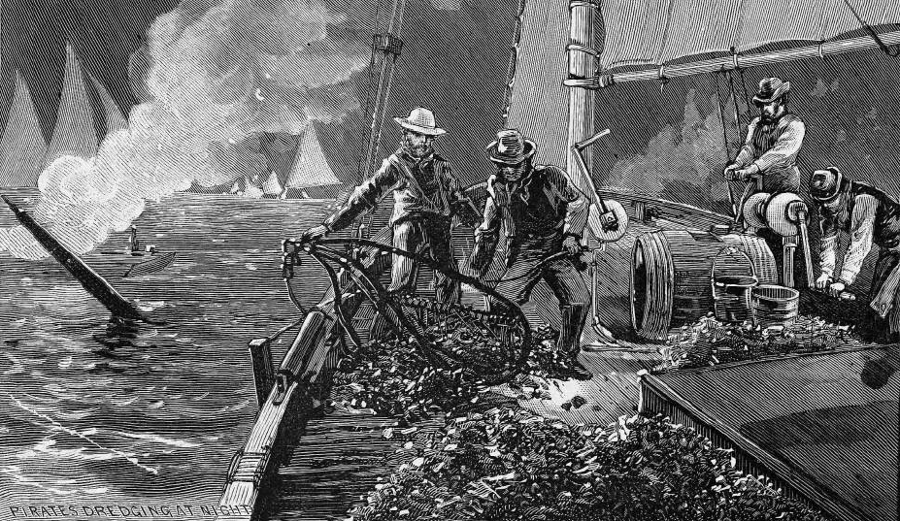

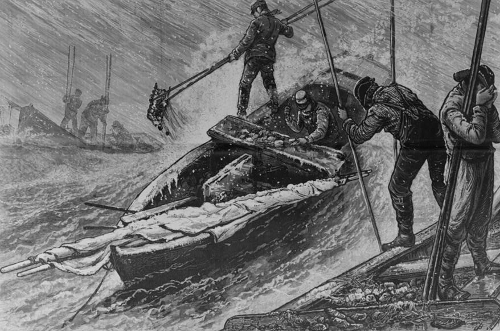

oysters used to be dredged with sailboats

Source: Popular Science Monthly, The Natural History of the Oyster (November 1874) and National Park Service,

Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Watertrails Network

oysters used to be dredged with sailboats

Source: Popular Science Monthly, The Natural History of the Oyster (November 1874) and National Park Service,

Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Watertrails Network

A female oyster might release 20 million eggs in one spawning, but the vast majority will be eaten or land on a soft surface or shifting sand (where they die). After fertilization, young Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) float for several weeks until they settle on the bottom of the bay, a tidal river, or along the Atlantic Ocean shoreline. The oyster larvae, in their pediveliger stage, use a "foot" to find a hard surface on which they can metamorphose into a juvenile oyster ("spat").

Once on a hard bottom as much as 25 feet deep, an oyster never moves from that spot again as it matures and grows for up to 20 years. If a storm carries a layer of sediment downstream, fish can swim to cleaner water until the sediments settle out. The oysters, trapped in one place on that same river bottom, will stop filtering food until the water clears. If the sediment cloud remains over the oyster bed for too long, oysters will die.

Shells of living and dead oysters gradually create a hard bottom in river estuaries or at the edge of the bay/ocean. As a result, areas where sediment flow may normally cover any bedrock may end up with a diverse pattern of hard substrate and muddy bottom, providing greater habitat options for plants and animals. Oyster bars have expanded, generation by generation, as young oysters settled on the shell of older oysters.

Source: Chesapeake Bay Foundation, The Incredible Oyster Reef

Oysters are filter feeders that strain their food from the water column; a single adult oyster can filter from 3 to 12.5 gallons/day. Overfishing in the 1900's, followed by diseases (Dermo and MSX) starting in the 1950's, has reduced the Crassostrea virginica population by 99%. Before that dramatic decline, the mass of oysters in the Chesapeake Bay had the capacity to filter all the water within the bay in less than a week, and may have consumed up to 75% of the carbon generated by algae in the shallow portions of the Chesapeake Bay by fixing it into shells and biomass of oyster bodies.1

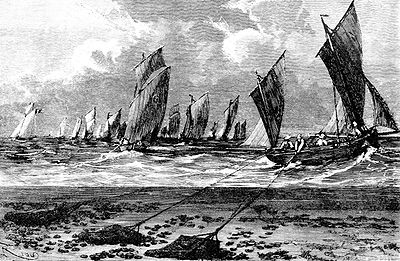

commercial oyster harvests in the Chesapeake Bay show the dramatic population decline in 50 years, due to overharvest and diseases (MSX and Dermo)

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Conserving the Chesapeake's Living Resources - Oyster

Individual oysters can adapt to waters disturbed by tides and storms, and oyster beds can adapt to rising sea levels. By one estimate, the water level in the Chesapeake Bay rose 10mm/year as sea level rose and the bay formed after the last Ice Age. Oysters were able to increase the height of their reefs by that amount. The size and extent of oyster reefs in the bay 400 years ago may have been determined by the available food in the water. The oysters were once so plentiful, and so efficient at filtering food, that the species filled its biological niche and there was no opportunity to expand further.2

The word "Chesapeake" may not be Algonquian for "great shellfish bay" despite years of traditional references to the meaning of that name, but idea behind that translation is appropriate. The Chesapeake Bay was "full" with oysters 400 years ago.3

Native Americans feasted from oyster bars in the Chesapeake Bay, in the saltwater portions of Tidewater rivers, and on the Atlantic Ocean edge of the Eastern Shore. Over the centuries, Native Americans tossed shells of oysters they ate into waste heaps next to the shoreline, creating "middens" of leftover shells near Native American towns.

oyster midden, now exposed and eroding

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Cultural Resources - Shell Middens

An occasional reduction in the size of the oysters layered in the mounds shows periods of intense harvesting, followed by reduced collection pressure during which oysters could grow larger again. The change in harvest patterns suggest the Native Americans allowed the oyster bed to recover, practicing sustainable management of the resource. Modern oysters are 30% smaller than those in the Chesapeake Bay 400 years ago. That size difference may reflect excessive harvest of the large oysters, but also an earlier harvest before oysters finish growing to full size. Quicker harvest allows collection of the oyster crop before diseases such as MX and Dermo can kill them.

Archeologists who have measured the size and age of oyster shells suggest that in the Archaic Period, harvesting focused on the larger oysters at reefs in deeper water. Later, in the Woodland Period, most oysters were collected from easier-to-access reefs near the shoreline. Larger oysters were collected occasionally from the deeper reefs, presumably for special events.

In 1891, a Smithsonian anthropologist wrote:4

oyster with hard shell of calcium

Source: US Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Crassostrea virginica

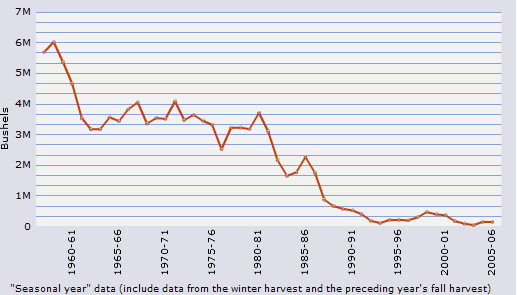

Oyster collecting relied upon simple technology - a stick, antler, or rock to break oysters free. The harvest was extensive, but not intensive. Oyster bars were not destroyed when Native Americans plucked oysters from the top. The "fishery" was sustainable, and oyster bars were common in shallow areas where water salinity was suitable. When John Smith sailed/rowed around the bay and its tributaries in 1608, his men struggled to get their shallop across shallow reefs of oysters exposed at low water; oyster bars were a navigation hazard.

Early English settlers were also able to harvest oysters in great quantities without reducing the ability of the species to recover. In 1686, Durand de Dauphine noted that his host had no difficulty obtaining several hundred pounds of oysters on short notice:5

Since 1900, and especially since the 1950's, oysters have fallen upon hard times in Virginia due to overharvesting, pollution, and disease. Those ancient reefs have been flattened and excavated by tonguing with double-sided rakes to dig oysters by hand, or by dredging to strip mine the oysters from a reef using wind- or motor-powered boats to drag a cage with a hard edge that rips oysters free.

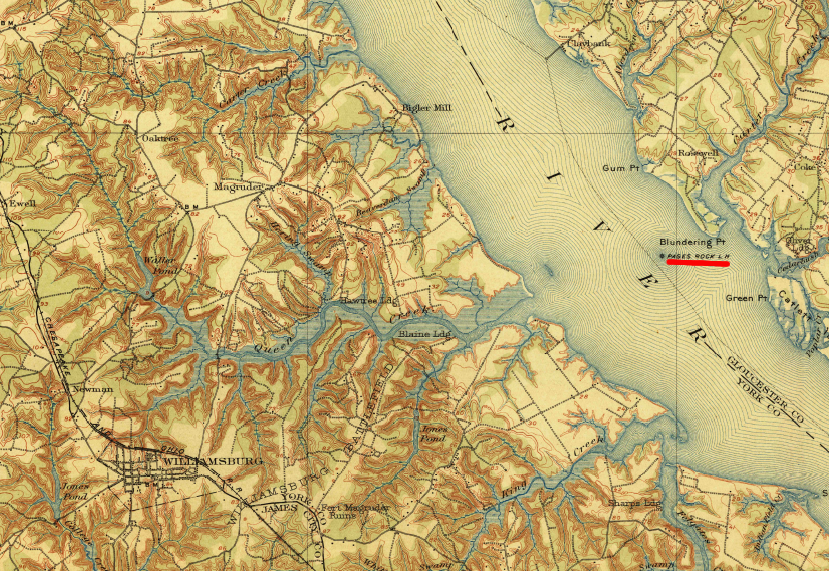

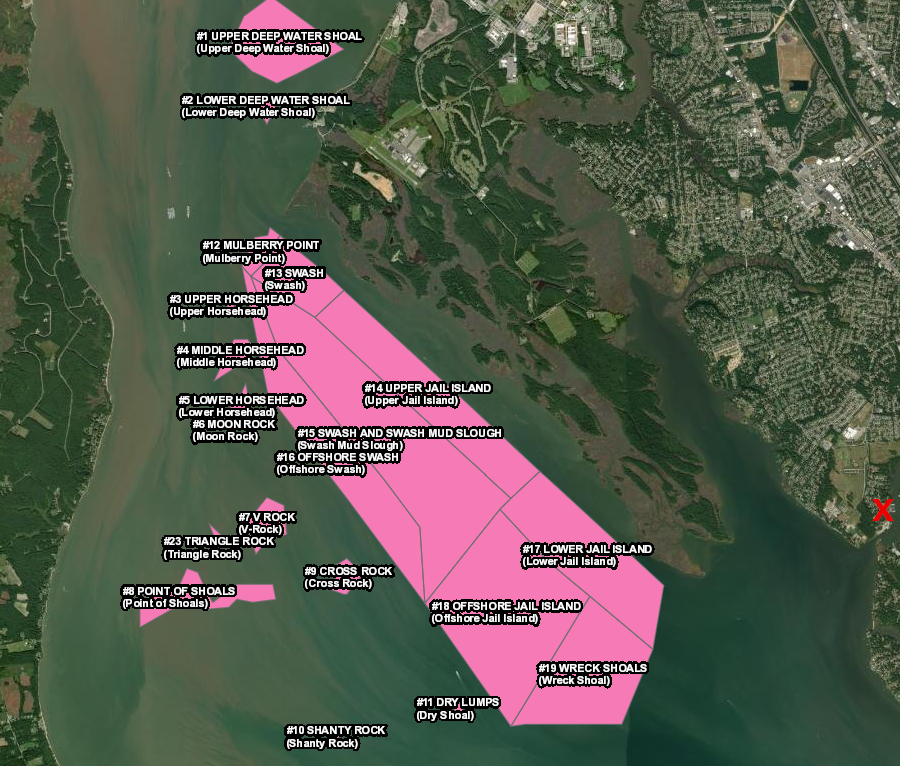

oyster reefs at the mouth of the York River were mapped as a navigation hazard to the early English colonists

Source: Huntington Library, Tyndall's draughte of Virginia 1608

New technology allowed watermen to remove oysters faster than they could naturally reproduce, while culture and law permitted extraction without consideration of the natural restocking rate.

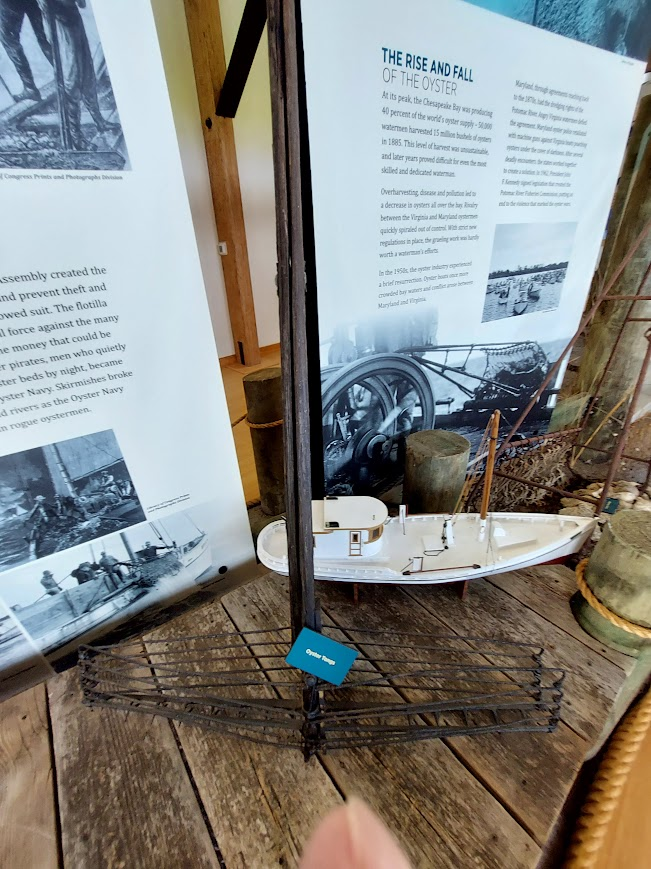

oysters in shallow water could be harvested using rakes, but oyster beds in deeper water required boats and long-handled tongs

Source: Library of Congress, Oystering on the Chesapeake and Fred, a young oyster fisher; working on an oyster boat in Mobile Bay

oyster tong and dredge at Belle Isle State Park visitor center

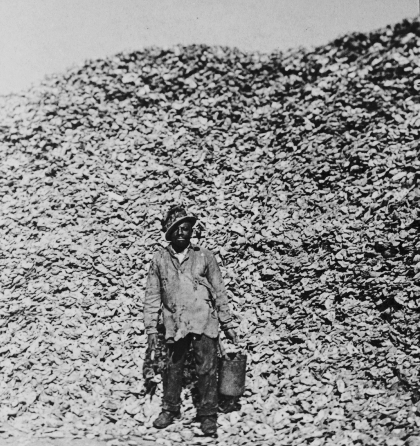

As the oyster shells were mined (ground up and used as grit in chicken feed, for fertilizer, or for road construction), the reefs disappeared. At Wreck Shoal in the James River, 4-6 feet of oysters have been removed. As reported by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science:6

Pages Rock Lighthouse, near modern-day Cheatham Annex of Yorktown Naval Station, as depicted on 1906 map

Source: US Geological Survey, Williamsburg 15x15 topo map (1906)

The biological impact of the destruction of the oyster population is significant:8

oyster shells removed from the Chesapeake Bay were often used for construction, rather than recycled to support another generation

Source: Library of Congress, A Virginian oyster shucker (c.1896) and Oyster pile, Hampton, Va.

Overharvest of Chesapeake Bay oysters is a classic example of the "tragedy of the commons." Virginia and Maryland did not treat reefs as a renewable resource. The state governments allowed watermen to mine the oyster populations in the same way that coal is mined today: scrape up the resource and haul it away.

Oysters grew on the river and bay bottoms, on submerged land owned by the state rather than by any single individual. There was no incentive for a waterman to leave behind any oysters when harvesting a reef - some other waterman would simply take the oyster, before it had a chance to reproduce.

States did not ensure enough young oysters would remain to repopulate reefs and support perpetual oyster removal. When regulations were passed to manage the harvest, state agencies failed to enforce those regulations consistently. Various ineffective efforts to manage the oyster harvest included limits on dredging, reduced seasons, and prohibition of "foreign" boats.

illegal oyster harvesting including dredging at night

Source: Harper's Weekly, The Oyster War in Chesapeake Bay (March 1, 1884)

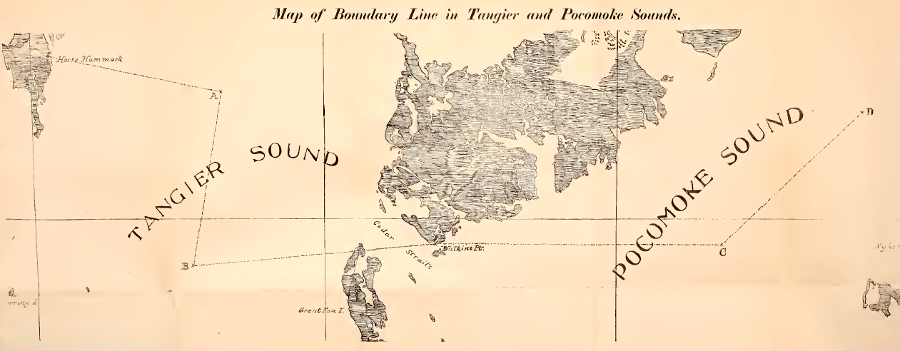

Foreign boats included Connecticut watermen who moved into the Chesapeake after overharvesting the beds in Long Island Sound - and also boats from across the state line. "Oyster wars" broke out between Maryland and Virginia, as each state tried to block watermen from dredging oysters on the "wrong side" of the state boundary. The Virginia-Maryland boundary arbitration in 1877, determined by the Black and Jenkins decision, was triggered by a desire to define control of oyster beds in Tangier and Pocomoke Sounds.

the Virginia-Maryland boundary was clarified in 1877 to resolve conflict over territory valued for oyster harvesting

Source: Report of the commissioner on the part of Maryland, for the re-locating and re-marking of the boundary line between Maryland and Virginia in Tangier and Pocomoke Sounds (1877)

Despite clarified boundaries, both local and out-of-state watermen continued to violate Virginia's laws on oyster harvesting. In 1882 and in 1883, Virginia Governor William Cameron led nautical expeditions from Norfolk to capture illegal dredgers in the Rappahannock River. In 1884, Virginia created a naval police force to ensure compliance with oyster regulations. The "oyster navies" of Virginia and Maryland fought with watermen and each other at times until the 1950's, until the oyster population had collapsed and the natural resource no longer justified the effort to control the harvest.9

In the 1890's, Virginia took action to address the loss of natural oyster reefs. Virginia's solution was to increase the supply of oysters, rather than deal with the demand of watermen to harvest an excessive amount. Political influence by the watermen (and the state's reluctance to fund a police force to ensure regulations were followed) blocked effective controls on hunting/gathering wild oysters.

Virginia's supply side strategy was to encourage private farming of oysters. Virginia initiated a privatization process to lease submerged lands, authorizing individuals and companies to create new oyster reefs. Private funding was mobilized to re-establish oyster populations in selected locations, by creating leaseholders of "private rocks."

Physically, new reefs were created by transporting old oyster shells from packing houses (or by mining even older ancient Native American middens) and depositing the shells on the leased portion of submerged land. Seed oysters were moved from beds on the James River to areas within the boundaries of leases.

Hauling shell was the easy part. The politically-challenging part was establishing a legal framework, so naturally-reproducing oyster beds remained open to public harvest but only the individual/company responsible for creating a private reef was allowed to remove oysters from that location.

watermen harvested oysters with 14-foot and 20-foot long tongs, and even in good weather it was hard labor

Source: Library of Congress, Favorite bed for small boats - Gathering and dressing oysters under difficulties

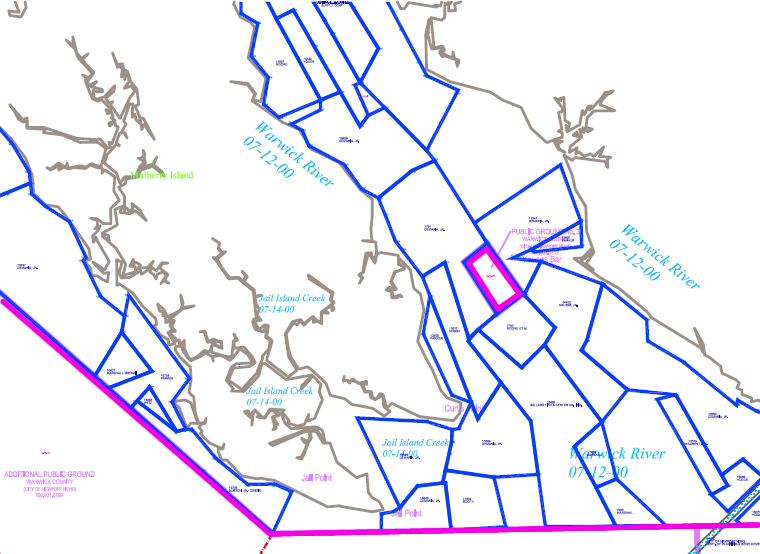

Virginia's privatization program began with identification of the remaining underwater sites where natural oyster production was sufficient to maintain interest in commercial harvest. These areas were mapped during 1892-94 by James Baylor, from the US Coast and Geodetic Survey.

Under the 1892 legislation passed by the General Assembly, local officials maximized the area defined as barren and thus left open to raking/tonguing/dredging by the public. The boundaries of the Baylor Surveys were drawn as straight lines to simplify the initial cost and administration of the surveys. As a result, polygons that included the full extent of where oysters were growing also included substantial buffers of submerged land where no oysters were reproducing naturally.

About 200,000 acres of the submerged bottom were designated as public oyster grounds, while 400,000 acres were made available for private leases. Baylor himself was a political progressive who thought private leases would encourage scientific management of oysters like a crop, replacing the hunting/gathering model where watermen exhausted the natural beds.

However, the business leaders with enough capital to lease submerged lands in Virginia did not raise strong objections to local efforts to draw broad boundaries for public oystering grounds in the Baylor Surveys. (In 1909, James Moore's resurvey of Baylor Survey tracts on the James River determined that 58% of the bottomland was devoid of oysters.)

Allowing excessive acreage minimized political conflict over excluding local watermen from traditional areas, and those planning to plant new beds on leased bottom did not desire areas where oysters were growing naturally. Barren bottomland allowed newly-planted oysters to grow to a larger, more-valuable size without competition from existing oysters.10

Boundaries of underwater beds were hard to mark, and easy to ignore. Once a portion of submerged land was included in a private lease, Virginia law permitted leaseholders to build watchtowers with armed guards to protect their crop from oyster rustlers. State law enforcement to protect private oyster beds was theoretically possible. However, direct action to deal with trespass (or alternatively, tipsters reporting violations to state officials) was more reliable a century ago... and is not uncommon today.

Oyster packing companies with political influence, and a desire to lease submerged lands, supported privatization. Virginia watermen willing to allow privatization in part because the private beds would be harvested by local tongers, who by law had to be Virginia residents, rather than by dredgers from other states. Also, under the 1902 Constitution of Virginia, the voting power of the watermen themselves was suppressed after the poll tax and other tools restricted the ability of low-income residents to vote.11

in the Warwick River, a small polygon (with purple boundary) of public rocks defined by the Baylor Survey is surrounded by private leases of submerged land (blue polygons)

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, The Wreck Shoals-James River Oyster Sanctuary Map

In contrast, Maryland watermen did not support privatization, and the state did not lease significant portions of its submerged lands until the 21st Century. In the 1900's, watermen ensured oyster reefs in Maryland's portion of the Chesapeake Bay, and in bays on the Atlantic Ocean shoreline, would stay public and open to commercial harvest. The downside is that state funding would be required to create new oyster beds in Maryland, since there was no incentive for private funding.

Public access to the areas where oysters were naturally reproducing, as documented in the Baylor Surveys, was incorporated into the 1902 Constitution of Virginia as Article XIII, Section 175. That policy survives in today's state constitution as Article XI, Section 3:12

After the Baylor Survey delineated the public oyster grounds where reproduction was occurring naturally, counties appointed oyster inspectors and surveyors to lease submerged lands for private oyster plantings, and to ensure compliance. That responsibility was shifted to the State Fisheries Commission in 1920.

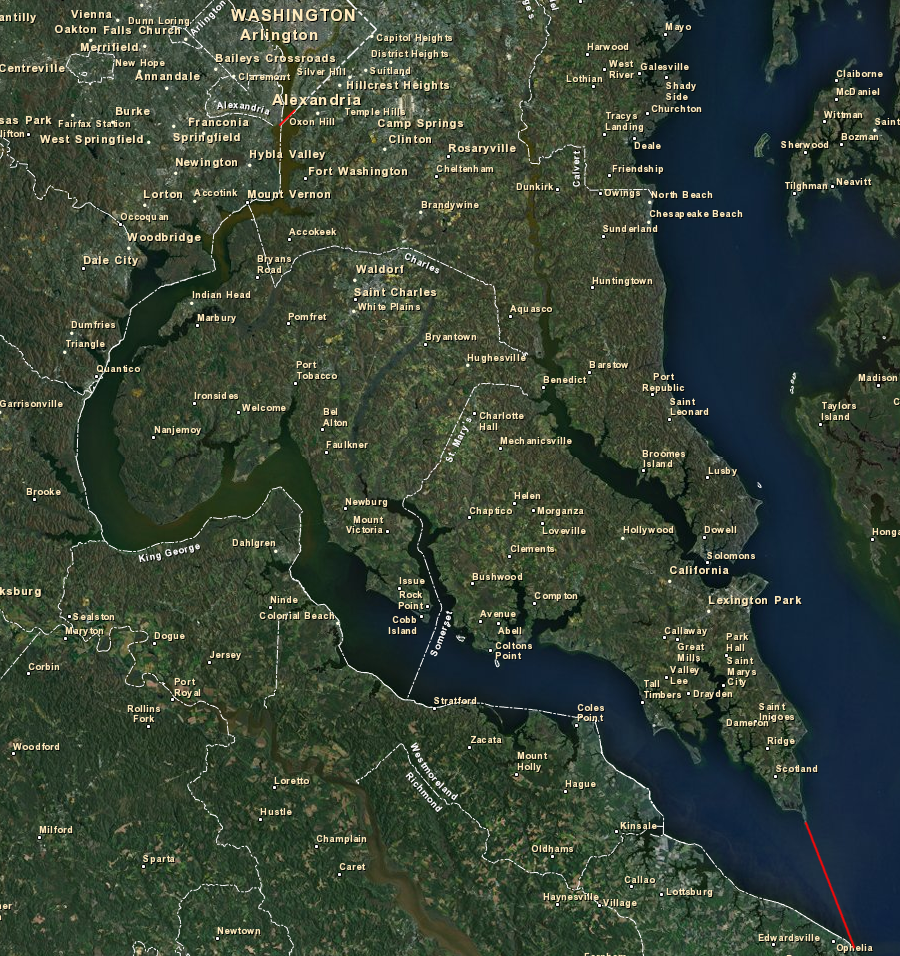

Based on the Compact of 1785, Virginia had equal rights to the river. The conflict between Maryland and Virginia over oyster management continued after World War II. In the 1950's, oyster dredgers from Virginia were famed for operating a "mosquito fleet" that illegally dredged oyster bars on Maryland's submerged land. Maryland threatened to break the Compact of 1785 and assert control over the river's aquatic resources, and Virginia threatened to bring suit in the Supreme Court. The two states then negotiated the Compact of 1958, and created the Potomac River Fisheries Commission (based in Colonial Beach).

an exhibit at the Morattico Waterfront Museum shows how many companies steamed oysters and shipped cans to distant customers

Opposition to the 1958 compact was strong in Tidewater Maryland, where watermen feared the new arrangement would lead to restrictions on public oyster bars and more leasing. From the perspective of many Maryland watermen, Virginia packing plants relied upon leased beds to provide most of their oysters, and Virginia officials did little to enforce restrictions on the public oyster bars (Baylor grounds).

One opponent tried to modify the Compact of 1958 to regulate recreational and commercial use of aquatic resources in the Chesapeake Bay, as well as the Tidewater portion of the Potomac River between the DC boundary and Point Lookout/Smith Point. Supporters of the compact may have increased publicity of the 1950's "oyster wars," to create support for the bi-state agreement. Opponents were able to force a statewide vote in Maryland, but voters approved the Compact of 1958, replacing the Compact of 1785.13

The Potomac River Fisheries Commission issues licenses for oystering, clamming, and fishing in the Potomac River downstream of DC, and Virginians get equal access to the resource according to the 1958 compact:14

the Potomac River Fisheries Commission has authority in the tidal Potomac River, downstream from the District of Columbia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC), which was created in 1968 to replace the State Fisheries Commission, issues leases for use of submerged land not included within the Baylor Surveys, ensures compliance with aquaculture regulations, and enforces state regulations on Virginia's waters and submerged lands.

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission also deals with modern-day poaching from leased beds, and illegal harvesting from sanctuaries and closed areas. The General Assembly authorized stronger penalties in 2013, after recovery of the oyster population from its lowest point in 1999 led to a boom in private leasing. Quick raids to scrape oysters from restricted areas on a foggy day can generate quick profits, and failure of some oyster restoration projects might be associated with poaching. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission approach to manage the oyster resource includes law enforcement:15

Menchville Marina in Newport News (red X), where many watermen bring harvested oysters, is near multiple reefs in the James River

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia Oyster Stock Assessment and Replenishment Archive (VOSARA)

Since oysters feed by filtering water, there have been claims that restoration of the oyster population will help restore the water quality of the Chesapeake Bay. Oysters extract nitrogen from the bay's water and fix it into their shells and flesh, so each oyster could be viewed as a tiny wastewater treatment plant. Oysters might serve to correct the overload of nitrogen in the bay, if source reduction of urban/agricultural runoff is not fully implemented as proposed in the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan developed by the Environmental Protection Agency.

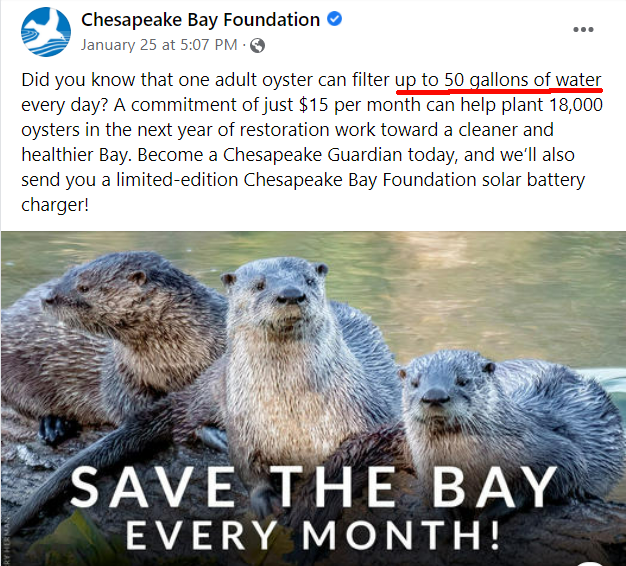

Though each oyster may do its tiny bit for water improvement, claims that they process 50 gallons a day are overstated. Even if true, a fully-restored population of oysters would not have a significant impact on nitrogen levels in the bay. The oyster harvest from the late 1800's-1920's reached 4 million-7 million bushels/year, and exceeded 1 million bushels/year until 1980-81 before dropping to a low of 18,000 bushels in 1995-96. If restoration is successful and harvest increased to 1 million bushels/year again, that would remove only 0.2 percent of today's nitrogen load.16

oysters filter water in the Chesapeake Bay, with claims of up to 50 gallons per day

Source: Facebook, Chesapeake Bay Foundation (January 25, 2022)

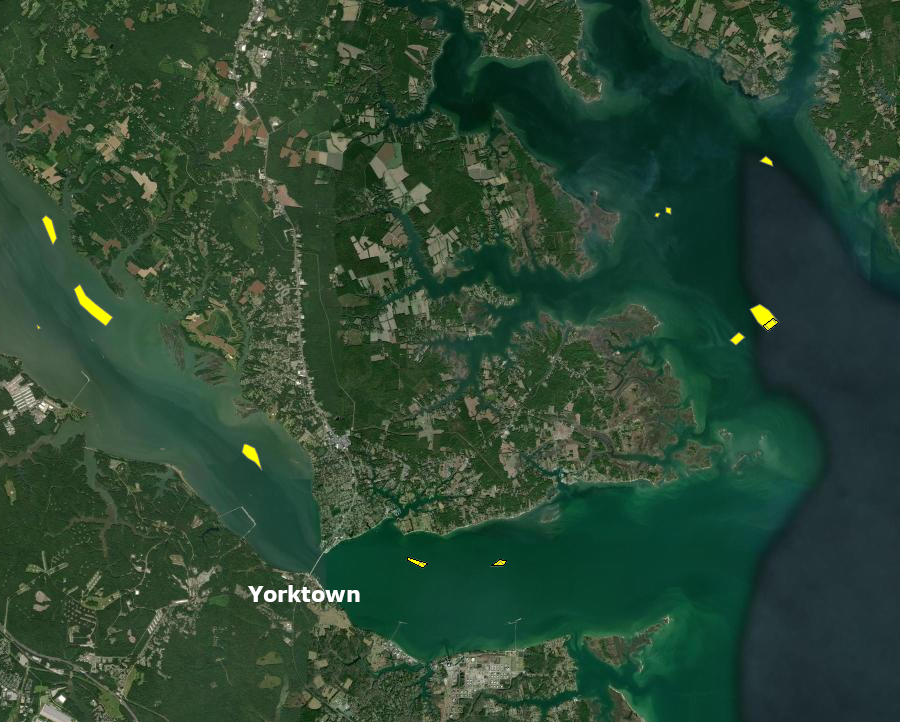

Oyster restoration efforts focus on recreating reefs of wild oysters, as well as aquaculture operations that increase the supply of "farmed" oysters. Hurricane Agnes in 1972 devastated the wild populations, sending a surge of fresh water and sediment into the bay. Heavy rains in 2018 damaged the reefs within the rivers on a similar scale, though the rainfall was spread throughout the year.

salinity in the York River is too low for large oyster reefs upstream of Yorktown Naval Weapons Station

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia Oyster Stock Assessment and Replenishment Archive (VOSARA)

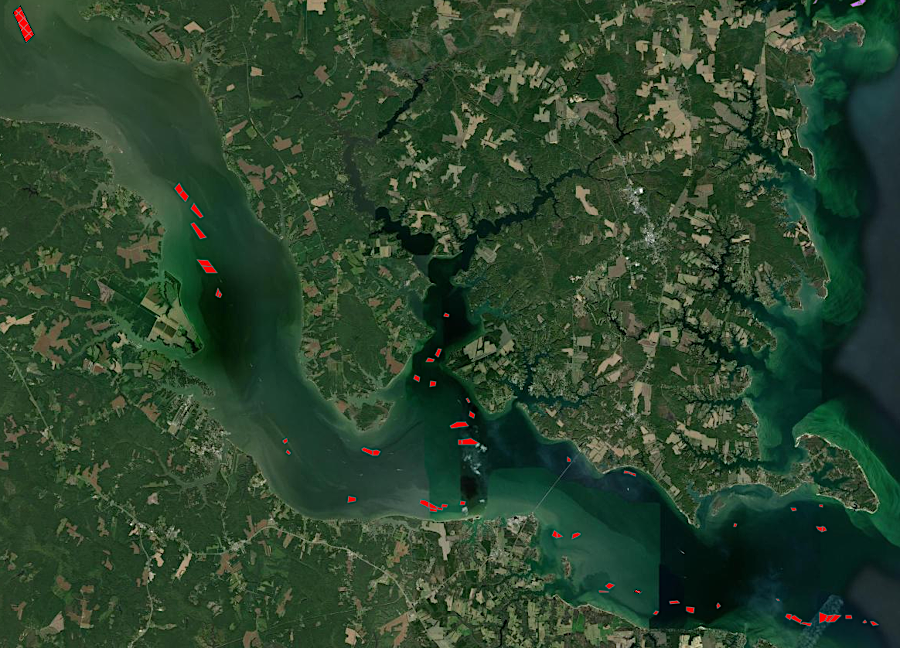

a deeper channel in the Rappahannock River allows salty water suitable for oyster reefs to reach further upstream

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia Oyster Stock Assessment and Replenishment Archive (VOSARA)

The salinity at the mouth of the Potomac River dropped to 7 parts per thousand, far below the normal 15-20 parts per thousand, and plans to plant a new sanctuary were postponed. The ability of oysters to outlast temporary surges of fresh water were stressed in 2018, and all died in one sanctuary planted in the Potomac River upstream of the US 301 Harry Nice Bridge.17

Source: AV Geeks, Virginia And Oysters

The 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, signed after a Federal court required implementation of a Total Daily Maximum Load (TMDL) by 2025 in order to achieve water quality that can support aquatic life, defined an oyster-related outcome:18

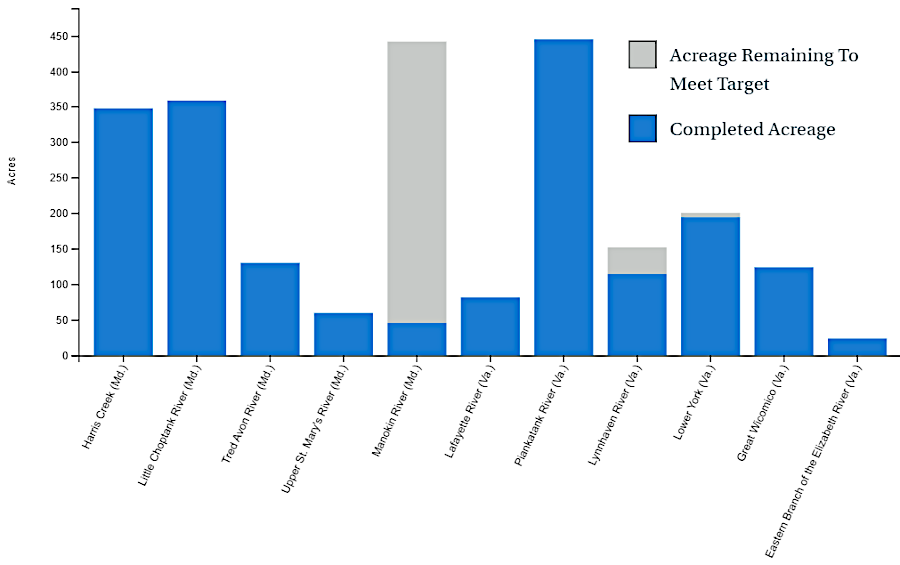

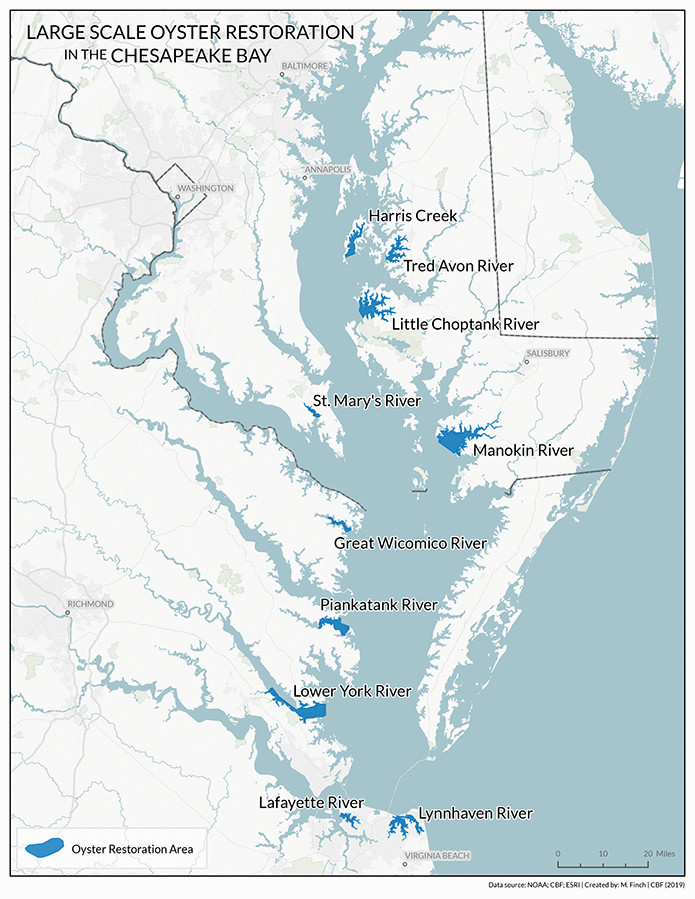

That obligation impacted Maryland and Virginia, the only two states in the Chesapeake Bay watershed where oysters could survive. Virginia planned to construct artificial reefs and establish healthy new oyster populations in the Lafayette River, Piankatank River, Great Wicomico River, Lynnhaven River, and the York River. In 2020, the state added the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River as a "bonus" oyster restoration project.

By 2022, the artificial reef construction targets had been achieved in four of the six rivers selected by Virginia. The York and Lynnhaven rivers were partially completed.19

by 2022, Virginia had completed oyster reef restoration projects in four rivers

Source: Chesapeake Progress, Oysters

Public oyster beds, where commercial harvest is authorized, are also enhanced by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC). Between 2000-2024 it invested $14 million in shell replenishment on the Rappahannock River, where 22% of the river bottom is suitable for oyster reefs. A study published in 2024 documented that oyster harvests from the area were worth $24 million over that time period, and that habitat improvements had resulted in the growth of more oysters. The replenishment increased brown shell volume on the reefs, which is the amount of oysters and shell above the bottom sediment layer that is a measure of health.

Key to the investment has been the authorization of public harvest on a three year rotation cycle. There are six oyster areas on the Rappahannock River where harvesting is permitted once every three years. More shells have increased the number of oyster spat in the first year, and in three years they grow to the desired harvest size for the commercial market.20

in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, Virginia committed to create healthy, functioning oyster reefs in five tributaries by 2025

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Large-Scale Oyster Restoration

oysters grow along the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Pacific Ocean

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Oyster Reefs

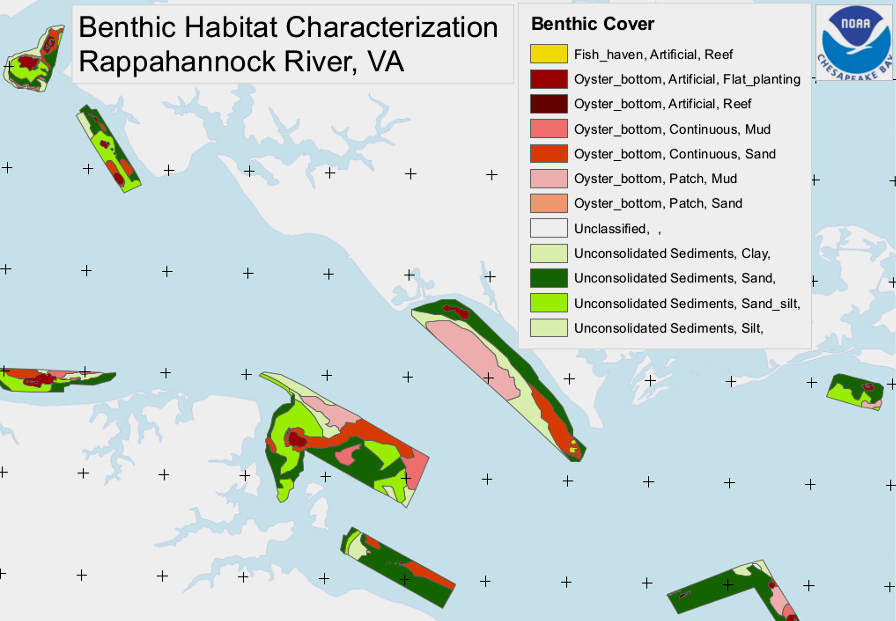

characterization of submerged river bottom at mouth of Rappahannock River; oysters need a hard surface to "set"

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Lower Rappahannock River, VA, Benthic Habitat Characterization

Source: Chesapeake Bay Journal, A Passion for Oysters (2023)

after the Civil War, Virginia's primary customers for oysters were in northern cities

Source: Library of Congress, Just received a supply of those celebrated oysters...