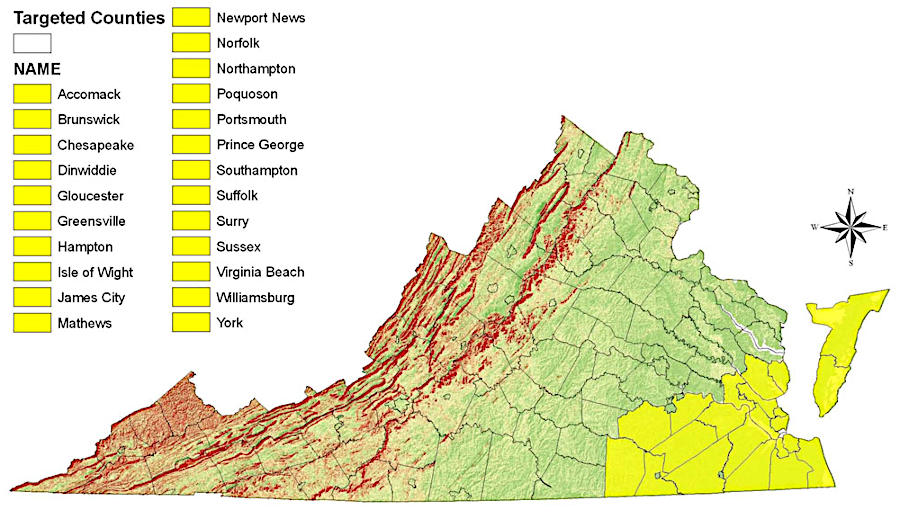

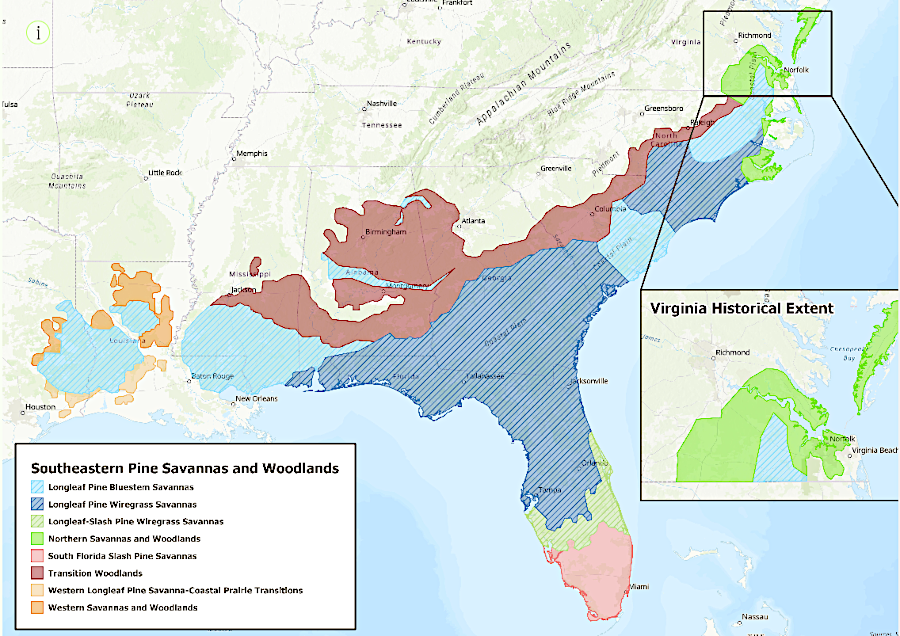

Federal funding in 2016 to restore and manage longleaf pine targeted counties thought to be within the historical range of the species

Source: Natural Resources Conservation Service, Longleaf Pine Initiative

Federal funding in 2016 to restore and manage longleaf pine targeted counties thought to be within the historical range of the species

Source: Natural Resources Conservation Service, Longleaf Pine Initiative

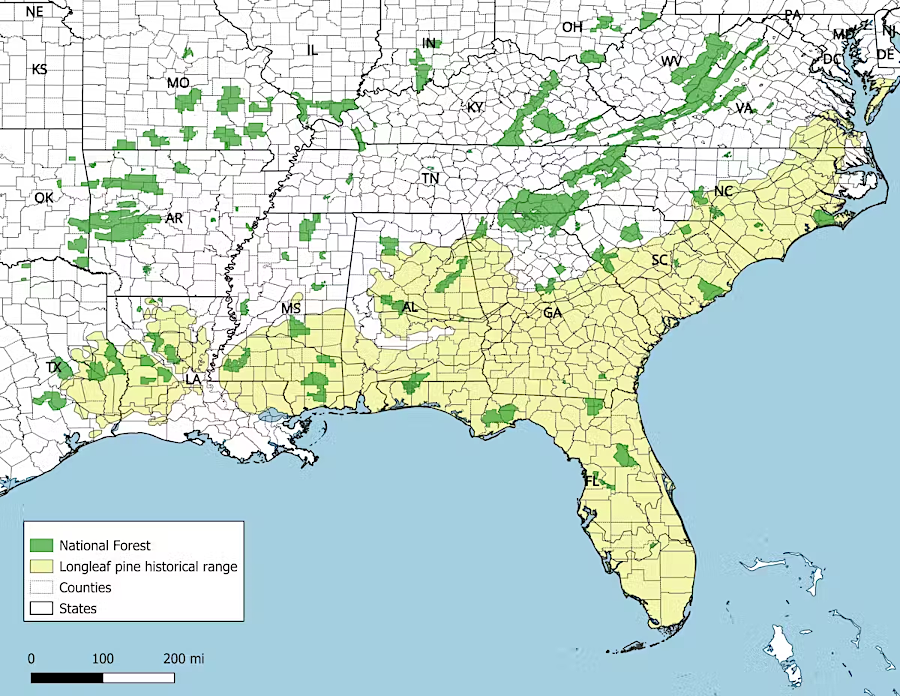

When European colonists arrived, up to 1.5 million acres of what is now Virginia were covered by longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests. It grew on the Coastal Plain south of the James River between the Atlantic Ocean and modern I-95, and had extended its range onto the Peninsula and Eastern Shore.

The Europeans would discover eight pine species and a wide variety of hardwood trees in Virginia. The longleaf pine, with its distinct 8-20" long needles, was the most common tree in the uplands of southeastern Virginia outside of the swamps.

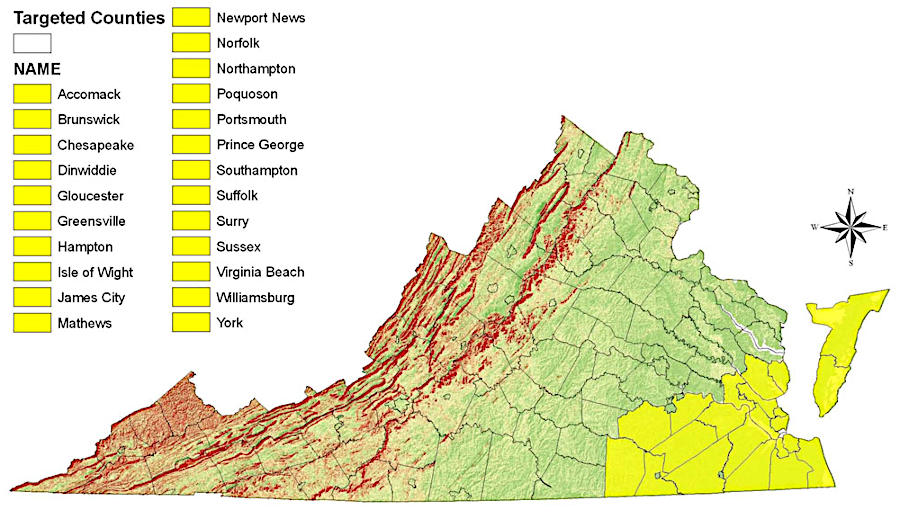

longleaf pine forests stretched from Texas to Virginia

Source: The Conversation, How fire, people and history shaped the South's iconic longleaf pine forests (by Andrea De Stefano)

The forests were valued for lumber (especially for building ships) and naval stores such as tar, pitch and turpentine. After the Civil War, uncontrolled logging was followed by fire and grazing by hogs which ate the roots:1

Colonization transformed the Virginia landscape. In 1893, a forester declared the longleaf pine in Virginia to be:2

by 1600, the longleaf pine was growing north of the James River and on the Eastern Shore

Source: Virginia Department of Forestry, The Effort to Restore

Virginia’s Native Longleaf Pine (Figure 1)

A 1998 census recorded only 4,400 longleaf pines in Virginia, growing on less than 800 acres. Some were from Louisiana seed that had been planted by Union Camp Corporation. Longleaf pine trees can live 250-450 years, surprisingly long for a pine species, but a 2007 survey identified just 134 longleaf pine trees in Virginia that were at least 57 years old.

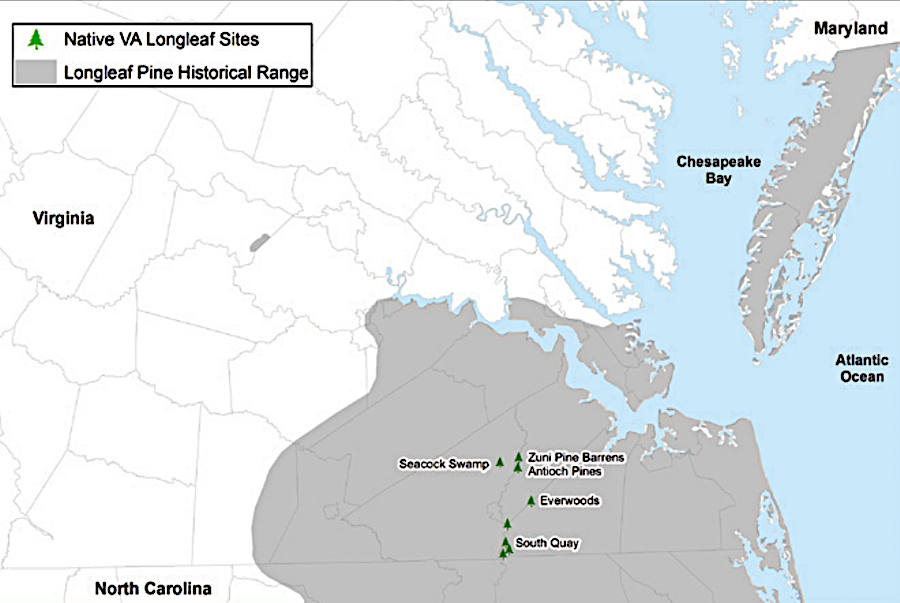

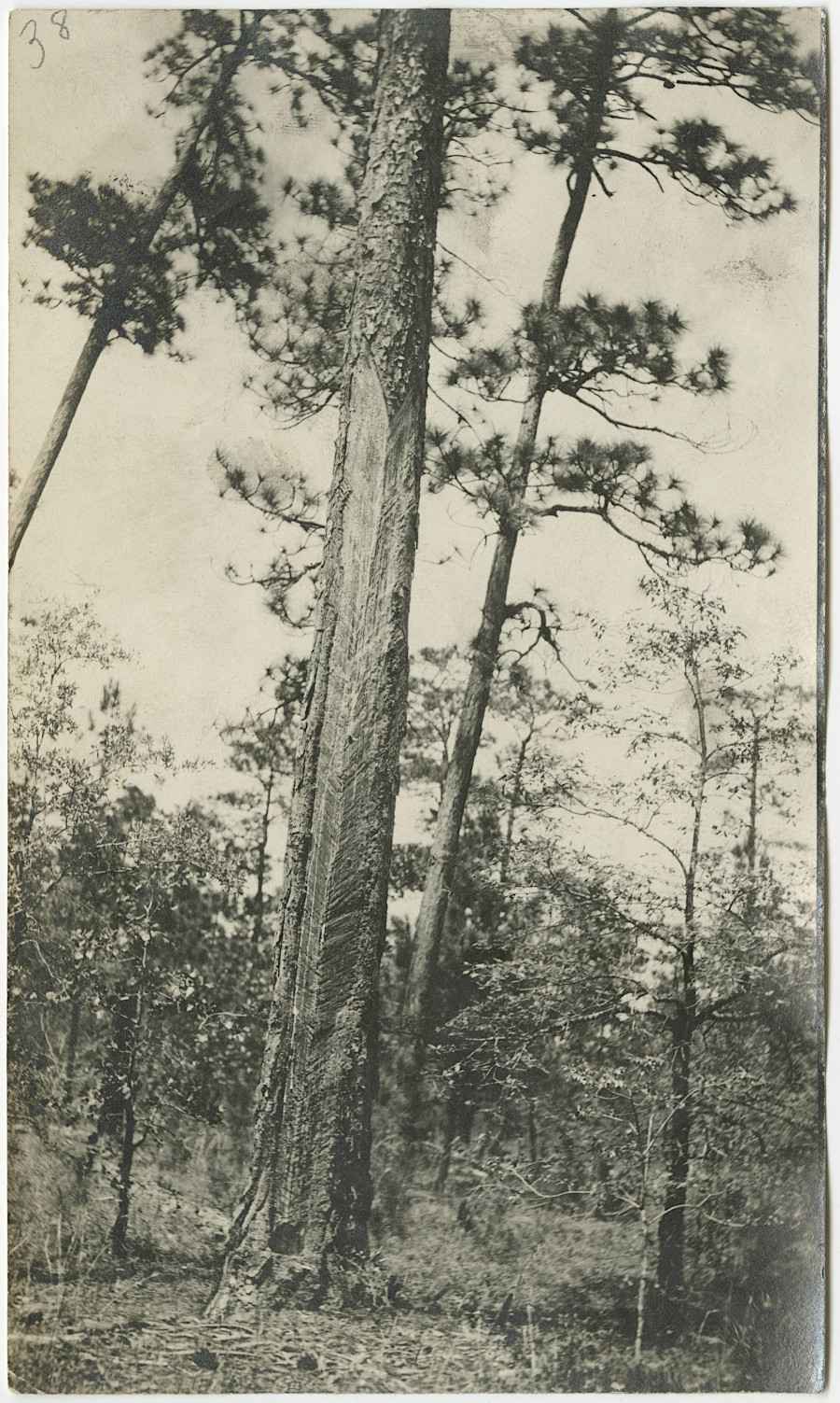

The trees were harvested for timber and "naval stores" required in the days of wooden ships. The sap of longleaf and loblolly pines was collected by carving a hole ("box") and gradually stripping away bark above it. The wound response of the tree lasted for five or more years until it no longer generated sap.

The sap was boiled to create turpentine, rosin, tar and pitch. During boiling, vapors were collected and distilled to make the turpentine. Trees that no longer generated sap could be cut and logs boiled to extract the last valuable sap.

Pine sap products were used to preserve the ropes on sailing ships and seal cracks between the wood planks. In 1608, the Jamestown colonists sent back to England "tryalls of Pitch and Tarre" in hopes of finding a way to make the private colony a profitable business for the Virginia Company investors.

The traditional naval stores business based on pine trees faded away after the Civil War, as steel ships became common. Today North Carolina residents (and the University of North Carolina sports teams) are still known as "Tar Heels," a relic of the historic pine processing industry.

The longleaf pine ecosystem is one of the most endangered in North America currently. The pines covers only 6% of their historic 90 million acres in the southeastern United States, stretching from Virginia to Texas. Thanks to modern restoration efforts, however, there are 5.2 million acres of longleaf forests now growing.3

Restoration efforts include raising longleaf pine seedlings in nurseries, acquiring land and replanting seedlings to establish new forests, and using prescribed fires to hinder growth of competing species. Stands in which longleaf pines compose nearly 100% of the trees were common in the past, and are being recreated now by government and non-government organizations.

Longleaf pine seeds must be in contact with bare mineral soil in order to germinate successfully. In the past, frequent fires burned away the leaf litter and facilitated soil contact. Pinus palustris requires full sunlight, so fires also reduced shade from competing shrubs, hardwoods, and loblolly pines (Pinus taeda ).

prescribed burns facilitate expansion of longleaf pine forests, since in the grass stage the species is fire-resistant

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Longleaf pine restoration efforts to expand

The longleaf pine ecosystem may have expanded substantially in the last 5,000 years as Native Americans started fires, in addition to the natural fires ignited by lightning. Anthropogenic fires artificially produced conditions that favored longleaf pine growth. Human land use practices have been a fundamental factor in the creation, then reduction and restoration of longleaf pine forests.

After the last ice sheet retreated, the species expanded from Florida and reached the James River by 1600. It is possible that longleaf pine would have extended its range north of the Potomac River by now, if colonists had not cut down the trees.

Trees growing on the northern edge of the range, north of the Neuse River in northeastern North Carolina, are considered to be a distinct population with unique character traits. The northern race of Pinus palustris has a higher water-use efficiency, apparently from differences in the photosynthesis process. Seed from Louisiana is no longer seen as an appropriate source for Virginia nurseries to grow seedlings.4

In anticipation of a warming climate, longleaf pine is being established north of its historic range in Maryland. Early in an "assisted migration" project, a hard freeze killed many of the seedlings and demonstrated why there is a northern edge to the tree's natural range.

Creating longleaf pine forests in eastern Maryland is expected to attract the red-cockaded woodpecker to start nesting again to Maryland. That endangered species is expanding its population in southeastern Virginia, where restoration and management of mature longleaf pines is creating the essential soft heartwood required for excavating nest cavities.5

The longleaf pine is uniquely fire resistant. After a seed germinates, the tree develops first in a "grass" stage. It grows a deep taproot for 3-15 years. Needles surround the terminal bud and help protect it from fire.6

Source: Smarter Every Day 2, This Tree LOVES FIRE (Longleaf Pine)

The last remaining natural stand of longleaf pine in Virginia is at the South Quay Conservation Site in the City of Suffolk. The privately-owned site is identified for conservation uses in the city's 2035 Comprehensive Plan. It is just north of the 3,700 acre South Quay Sandhills Natural Area Preserve, state-owned land managed by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation.

In 2024, city officials approved a permit to mine sand on 212 acres of private land that included the South Quay Conservation Site. A consultant for the developer reported that there was no remaining longleaf pine on the property, but state officials expressed concern that removing the sand would block any future efforts to restore the pine species there.7

longleaf pine extended its range to Virginia by 1600

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Longleaf Pine Habitat in Virginia

to "box" a pine and obtain sap for about 5 years, a hole was cut and bark was gradually peeled away above it

Source: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Folder 0173: Turpentine: Tree Tapping: Scan 1