loblolly pines at Conway Robinson State Forest are evergreens, with needles shed after a few years

loblolly pines at Conway Robinson State Forest are evergreens, with needles shed after a few years

Worldwide there may be over approximately 73,00 tree species, of which around 64,000 tree species have been documented. The undocumented trees are thought to be primarily in the tropics.

There are over 900 tree species in North America. The Flora of Virginia documents nearly 3,200 plant species which are native to Virginia or have become naturalized within the state, and Virginia has at least 350 species of trees.

Early English colonists introduced apple and peach trees, as well as the red mulberry in hopes of developing a silk industry. Red mulberries are now very common and many of the native white mulberries include red mulberry genes, as a result of hybridization over the last 400 years.

The evergreens retain leaves/needles throughout the year. Deciduous species go into the equivalent of hibernation for the winter, dropping leaves and storing sugars/protein/water in the roots. Starch is converted to sugar within cells, providing an antifreeze for protection against the cold.1

pines drop needles at various times so some are always present, while deciduous trees drop all leaves in the Fall

pine plantation in King William County

According to the Virginia Big Tree Program at Virginia Tech, which has documented 2,000 trees in the state, the oldest tree in Virginia is a water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) in Greenville County. It is thought to be at least 600 years old. Bald cypresses in the Cypress Bridge Swamp Natural Area Preserve in Southammpton County are estimated to be over 1,000 years old

The state's second-oldest living tree is a white oak (Quercus alba) in Brunswick County. It is 90 feet high, with a trunk circumference of 331 inches. In 2022, no other living white oak in the United States was larger.

Virginia's tallest trees are 140 feet high. Several have grown to that height, including a Southern Red Oak (Quercus falcata) in James City County, a Red Hickory (Carya ovalis) in Caroline County, and a Mockernut Hickory (Carya tomentosa) in an undisclosed location.2

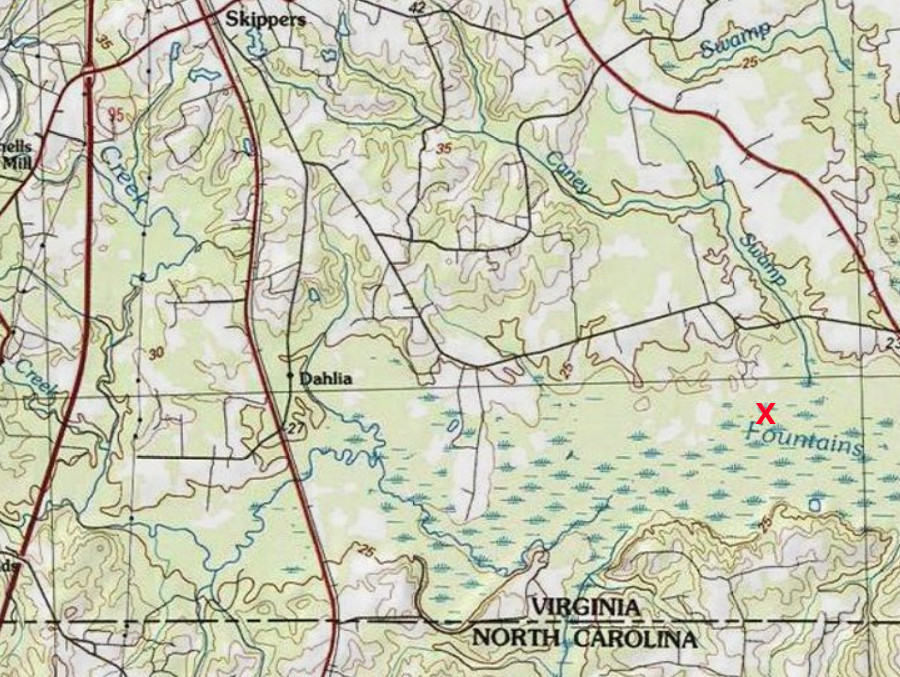

a water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) in a swamp along Fountains Creek, a tributary of the Meherrin River, is the oldest tree in Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Trees provide a wide range of ecological services. Trees provide habitat for nesting birds and squirrels; food for cicadas, caterpillars, and deer; and overnight shelter for owls and vultures. Trees prove shade and scenic beauty for humans. Retaining/establishing a tree buffer on the edge of parcels being developed is a common requirement in local zoning ordinances.

Trees maintain pervious surfaces that help recharge groundwater aquifers, and reduce stormwater runoff. The first quarter inch of rain can be intercepted by leaves.

Trees also retard erosion of sediment, nutrients, and road salt into nearby streams. The value of a tree buffer is recognized by the requirement in the regulations enforcing the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act that a 100-foot wide buffer must be protected along perennial streams in jurisdictions closest to the bay.

The "Save the Bay" effort to restore the Chesapeake Bay included a specific target for forest restoration: "Expand urban tree canopy by 2,400 acres by 2025." That target was identified in part because in the five years after 2013, the 663,667 acres of trees in the watershed were reduced by over 1%:3

Since Virginia has a mild climate and gets over 40" of rain each year, trees grow naturally on almost every patch of soil. In abandoned farm fields and forests where trees have been clearcut, the natural process of plant succession will produce a forest within the lifetime of the average human being.

Pines are early-succession trees. The wind blows pne seeds, with attached wings, into fields that have been created by natural storms or land clearing by farmers/developers. Three common species are Eastern white pines (with 5 needles in each bundle), loblolly pines (with three needles), and Virginia pine (with 2 needles). Eastern white pines are adapted to a colder climate, so naturally they were found at higher elevations. Virginia pine was most common in the Piedmont, while loblolly dominated in sandy soils of Coastal Plan.

However, the range of loblolly pine has been expanded by foresters planting it for faster production of lumber and pulp. Extensive timbering and production of "naval stores" (tar and turpentine) in the 1800's almost eliminated the longleaf pine from southeastern Virginia. Until recently, timber companies planted almost only loblolly pine. Without regular tree harvesting and other land disturbing activities, the forests of Virginia would have far less loblolly pine and far more deciduous hardwood species.

the forest which had grown up in the median of I-64 was removed for a widening project in 2019

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, I-64 Widening

Virginia's climate supports development of the Eastern Deciduous Forest, with a high percentage of hickories and oaks. Heavily urbanized areas still have some percentage of the landscape occupied by trees. The 250,000 residents in Arlington County are surrounded by 750,000 trees.4

Tree roots grow in the top two-three feet of soil, spreading radially from the trunk. The only Virginia tree with a taproot is the longleaf pine. Like a white oak, a longleaf pine will invest its early energy into growing the root system rather than push a trunk upwards.

Mycorrhiza in the soil are essential for tree roots to obtain water and nutrients. In a symbiotic exchange, roots share carbon with the fungal hypha in the development of a "wood wide web."5

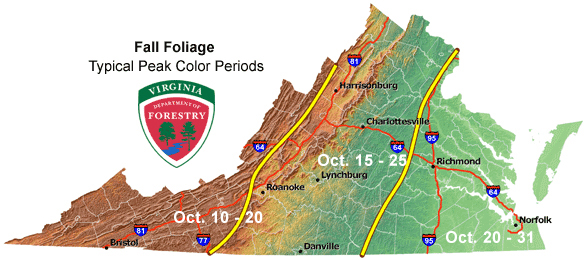

carotenoids produce yellow, orange, and brown colors, while anthocyanins produce red colors in September-October

Source: Virginia Department of Forestry, Fall Foliage

changing colors in Shenandoah National Park attract tourists each Fall

Source: Shenandoah National Park, Fall Colors from Big Run Overlook

corky abscission layers form at the base of leaves on most deciduous trees, and leaves break off in October-November

wounds can allow fungi to get into heartwood, weakening trees that then fall during storms

witch hazel, the last tree to flower each year

(on Blue Ridge Parkway at Mabry Mill)

in open fields without competition, trees can grow fast and produce wide annual rings

dead trees provide essential food and habitat while still standing and branches gradually fall off

Source: Friends of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, A Sedimental Journey: How Historic Deforestation Degrades Waterways Today by Chris Bolgiano

deciduous trees replace their leaves (food factories) annually

Source: The Nature Conservancy in Washington, The Power of Trees

an emerging tulip poplar leaf shows its distinct shape from the beginning

Source: USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab, Liriodendron tulipifera, Tulip Poplar

clumps of mistletoe are easily spotted in winter

grape vines can become almost a foot thick, as the leaves take advantage of sunlight in the canopy

fungal hyphae consuming dead tree cells can produce "turkeytail" and other mushrooms

yellow bellied sapsuckers drill through bark, then return to feed on the sap and insects that were attracted to it