red-cockaded woodpeckers (Picoides borealis) search for insects and spiders underneath pine bark, but also eat seeds and berries

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Red-cockaded Woodpecker Proposed Downlisting

red-cockaded woodpeckers (Picoides borealis) search for insects and spiders underneath pine bark, but also eat seeds and berries

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Red-cockaded Woodpecker Proposed Downlisting

The seven-inch long red-cockaded woodpecker (Picoides borealis) has a line of red feathers on its head. The bright color, sandwiched between white and black feathers, resembles the colored ribbons that decorated hats ("cockades") in the 1700's. In the War of 1812, volunteers from Petersburg wore cockades in their caps, and President Monroe declared Petersburg to be "Cockade City" in honor of their service.1

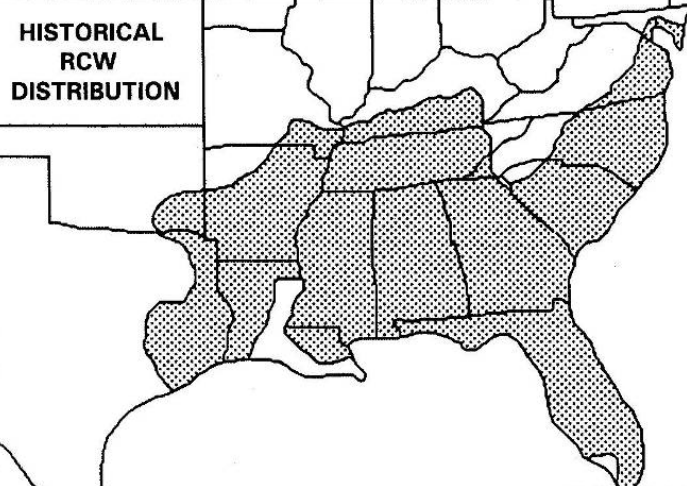

The red-cockaded woodpecker is on the list of endangered species because its habitat, open longleaf/loblolly pine forests maintained by frequent fire, has been reduced dramatically. Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) savanna once spread across 90 million acres from Texas to New Jersey, but is now reduced to less than 3% of that original range.

Virginia is at the northern edge of the range for longleaf pine forests and red-cockaded woodpeckers

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Red-cockaded Woodpecker Proposed Downlisting

The bird once had access to a million acres of forest savanna in Virginia, mostly south of the James River. Red-cockaded woodpeckers lived in Maryland until 1960,breeding in large stands of mature loblolly pines until they were harvested for timer. The birds have been transient visitors since then. As pine forests mature from their status of marginal to preferred habitat, red-cockaded woodpeckers from Virginia may expand their breeding range north into Maryland again.

By 2005, only 200 native longleaf pines trees remained in Virginia. The red-cockaded woodpecker was listed a "endangered" in 1970, when there were only 4,000 clusters (groups of cavity trees used by one or more woodpeckers) remaining in the entire United States. The species had experienced a genetic bottleneck, and was at risk of going extinct.2

The red-cockaded woodpecker ("RCW") populations declined as the longleaf pine forest disappeared:3

The red-cockaded woodpecker excavates a cavity in living longleaf pines, often mature (60-100-year old) trees suffering from fungal red heart disease. The species does not drill holes in dead trees like other woodpeckers. The birds are the primary creator of cavities in the southern pine ecosystem; secondary cavity nesters rely upon the hole for roosting or nesting. A family group of red-cockaded woodpeckers will create up to 20 cavity trees (a "cluster") across as many as 60 acres. The birds peck at the cavities to keep resin flowing, perhaps as a deterrent against rat snakes and other predators.

The birds are cooperative breeders. Male offspring remain with the parents for a year to brood eggs, while female offspring typically disperse to search for new breeding sites. The males stay behind to feed the next generation of nestlings for up to six months:4

Longleaf pines are the only tree in Virginia that grows a taproot. Seedlings spend up to a dozen years in a "grass stage" with vegetation low to the ground, as energy is devoted to expanding the root system. Longleaf pines are adapted to grow where fires are common. The small amount of grass-like material on the surface will burn, but the root collar can resprout.

The grass stage is followed by the "bottlebrush" stage, when trees grow about four feet straight up with no branches. As branches are finally created, saplings grow into what looks like a standard pine tree. Longleaf pines grow for 30 years before they begin to produce seeds.5

In 1998, The Nature Conservancy purchased a 2,700-acre tract of loblolly pine forest in Sussex County to create the Piney Grove Preserve. At the time, it was the only documented location for the red-cockaded woodpecker in Virginia. The Nature Conservancy began to harvest the loblolly pines and replant longleaf pines, in a long-term initiative to increase habitat for the endangered woodpecker.

Woodpeckers were captured in South Carolina from a stable population and transplanted to Piney Grove in 2005. The transplant was successful in expanding the number of breeding colonies, filling the available habitat on the Piney Grove Preserve.

The Commonwealth of Virginia purchased more acreage in 2009 and established the Big Woods Wildlife Management Area. Prescribed fires in 2015 and 2016 burned over 2,000 acres, helping longleaf pine to outcompete loblolly pine and hardwoods.

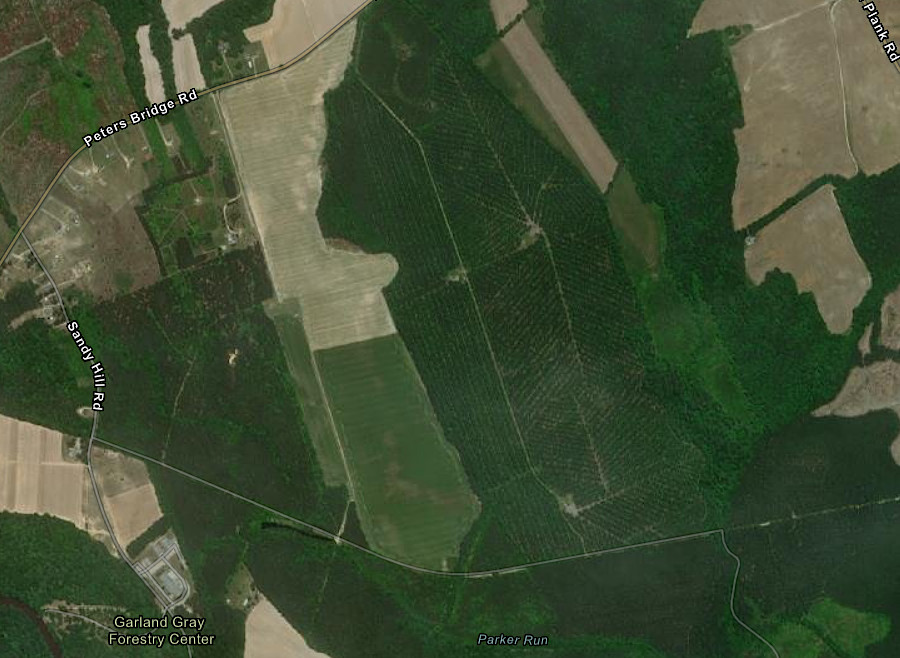

Initially the longleaf seeds that were collected from remaining trees in Virginia were grown to transplantable seedling size at a nursery in North Carolina. As a sign of the state's commitment to longleaf pine restoration, the Virginia Department of Forestry upgraded its Garland Gray Nursery in Sussex County. In 2018 the first crop of all-Virginia longleaf pines was planted on the nearby lands of the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe.

longleaf pines are grown by the Virginia Department of Forestry at the Garland Gray Nursery in Sussex County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In Sussex County, the Virginia Department of Forestry and Department of Wildlife Resources manage Big Woods State Forest and Big Woods Wildlife Management Area as one unit. The habitat in Sussex County provided by the Big Woods State Forest, Big Woods Wildlife Management Area and The Nature Conservancy's Piney Grove Preserve was expanded in 2021 by the creation of the 446-acre Piney Grove Flatwoods Natural Area Preserve, resulting in a 10,000-acre conservation area.

As desired, in 2019 a pair of red-cockaded woodpeckers from the Piney Grove Preserve carved out a nest in a pine tree at the Big Woods Wildlife Management Area. A biologist with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources described why cooperative land management was essential to the recovery efforts:7

cavities for nest sites were created artificially to accelerate recovery of red-cockaded woodpeckers

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Red-cockaded Woodpecker Proposed Downlisting

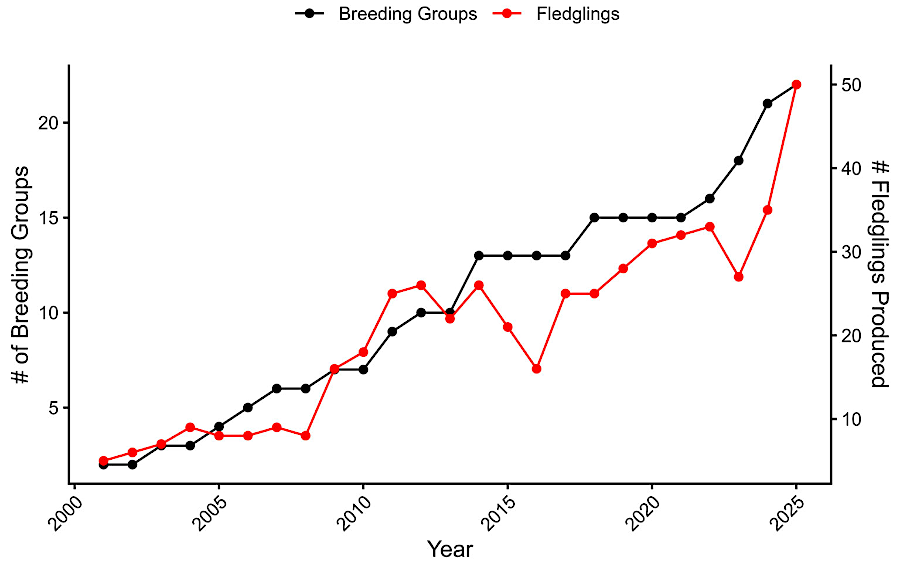

In 2018 and 2019, the number of breeding groups in Virginia reached 18. In 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed reclassifying the red-cockaded woodpecker as "threatened" rather than "endangered."8

In 2022, Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources biologists counted 74 red-cockaded woodpecker adults in the 2,204-acre Big Woods Wildlife Management Area and the adjacent Piney Grove Nature Preserve. In 2019, 2020, and 2021, two young red-cockaded woodpeckers fledged from nests but in each of those years they were lost to predation or other natural causes. In the 2023 winter count, one of the two 2022 fledglings was identified in Big Woods Wildlife Management Area. That sighting demonstrated how increasing the suitable habitat could trigger population recovery.

In 2024 there was a record-breaking number of fledglings at the Piney Grove Preserve. Habitat restoration in the 3,200 acre preserve, and in the nearby the Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (WMA) and Big Woods State Forest, had increased the number of breeding groups. In 2025, the number of fledglings increased by a surprising 50%, perhaps because the 22 breeding groups which had developed engaged in fewer territory-boundary skirmishes. Peaceful co-existence across the 10,000 acres of managed land led to more birds.9

Source: Wild Hope, Sparking fires... to save a woodpecker?

in 2022, the habitat at Big Woods Wildlife Management Area and Piney Grove Nature Preserve supported 74 adult red-cockaded woodpeckers

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Returns

One of the largest red cockaded woodpecker recovery efforts has been at Fort Liberty (formerly Fort Bragg) in North Carolina. Biologists were surprised to discover the largest number of birds were concentrated in the disturbed areas of the base. Further research revealed that use of tracer bullets, artillery, and other live ammunition had created a pattern of low-intensity fires in the longleaf pine forests, creating the preferred habitat.10

the number of red-cockaded fledglings increased 50% in 2025

Source: Center for Conservation Biology, College of William and Mary, Piney Grove’s Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Rebound

red-cockaded woodpeckers depend upon mature longleaf or loblolly pines for excavating nest sites

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Closer vertical shot of trees