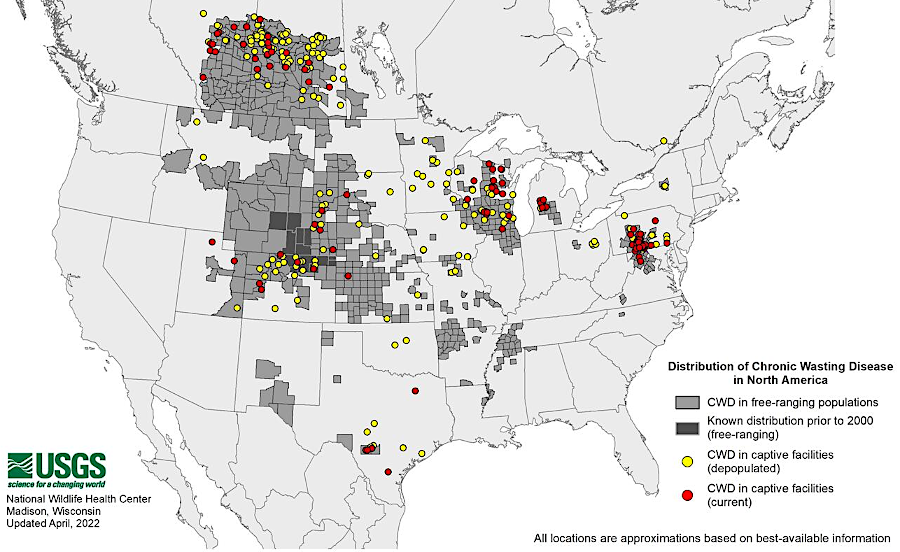

by 2022, Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) had been detected in 30 US states and four Canadian provinces

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Expanding Distribution of Chronic Wasting Disease (April 1, 2022)

by 2022, Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) had been detected in 30 US states and four Canadian provinces

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Expanding Distribution of Chronic Wasting Disease (April 1, 2022)

Chronic Wasting Disease is a fatal neurological disease to deer, caused by malformed proteins known as prions. The protein causes holes to form in brain tissue. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (known until 2020 as the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries) states that it is slow to kill deer but the disease is always fatal:1

There is no evidence that the disease can be transmitted to humans yet, but it is not clear that meat from an infected deer is safe for consumption. The state wildlife disease biologist told an overflow audience of concerned hunters in 2019:2

Infected deer can live for 18-24 months, so hunters are likely to eat some venison from healthy-looking deer without knowing that the animal was diseased. Late in the infection state, deer act confused, loose their normal fear of hunters, and ultimately starve to death. Hunters are unlikely to harvest animals in the last stages of the disease, but those deer may be killed in a collision with a vehicle. Drivers, State Police, and Virginia Department of Transportation personnel can be exposed to the prions when moving carcasses off the road.

Deer can shed prions across their natural territory before dying from severe emaciation. Prions are excreted from infected deer via saliva, feces, and urine. Other deer ingest the prions from contaminated soil and water. There is little potential to eliminate the disease from an area, once it has become common. The initial strategy in Virginia was to keep it from becoming established.

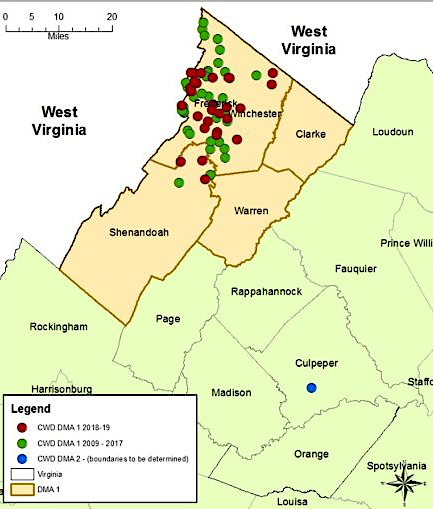

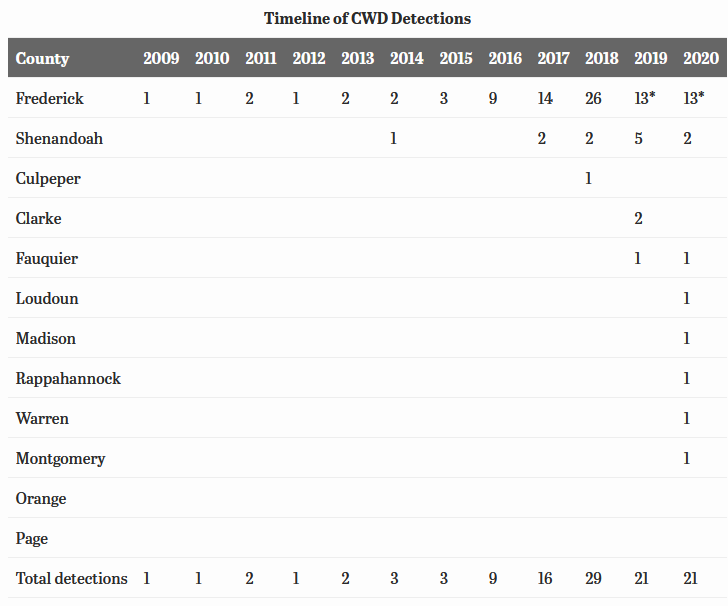

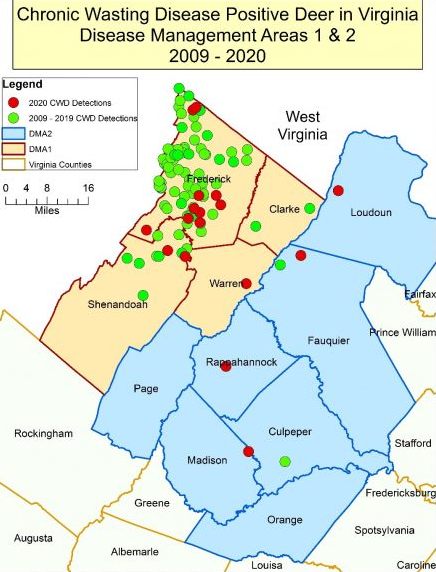

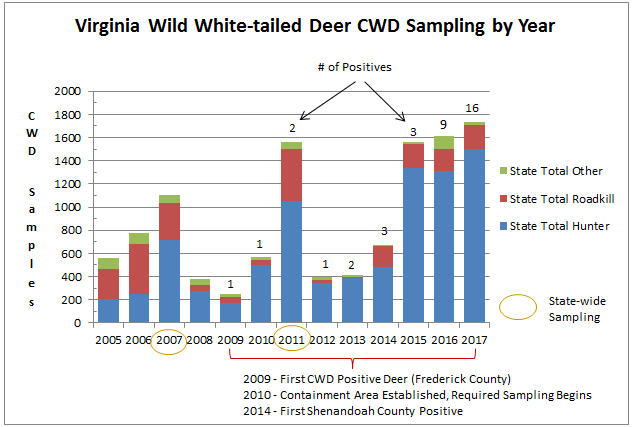

Between 2009-2018, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF) identified three counties where deer suffer from Chronic Wasting Disease. Later testing expanded the number of counties where deer were known to be infected.

The first infected deer was found in Frederick County in 2009. Presumably it had crossed the border from Hampshire County, West Virginia, where the disease had been recognized in 2005. All the infected deer were located very close to the West Virginia state line until 2013, when the disease spread further. In 2014, the state agency identified the first buck with the disease in adjacent Shenandoah County.

An infected deer was discovered in Culpeper County in 2018. At the time, there was no evidence of deer with chronic wasting disease in the counties between Frederick/Shenandoah (Warren, Rappahannock, Page, and Madison). Unless the infected deer migrated unusually far, that gap reflected insufficient testing rather than absence of the disease. Road kill was also tested and taxidermists were cooperative in providing samples, but evidently some sick deer were present but not identified between Culpeper and Shenandoah/Frederick counties.

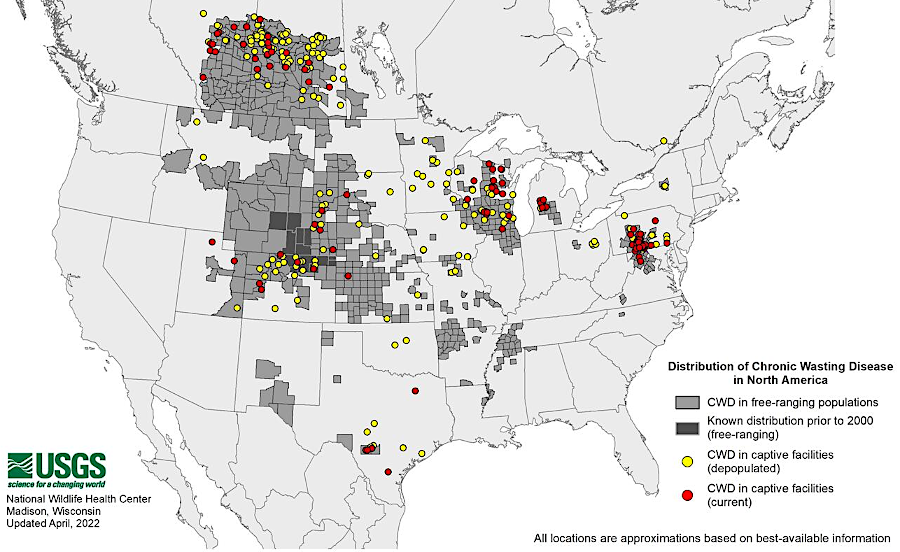

starting with a cluster in Frederick County, Chronic Wasting Disease was identified in three Virginia counties between 2009-2018

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Chronic Wasting Disease Surveillance and Response Plan, 2014 - 2019 and Tracking Chronic Wasting Disease in Virginia

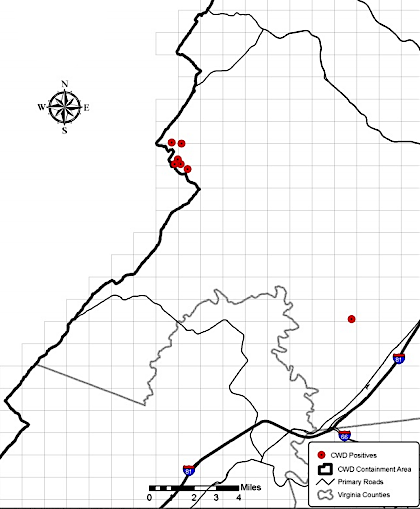

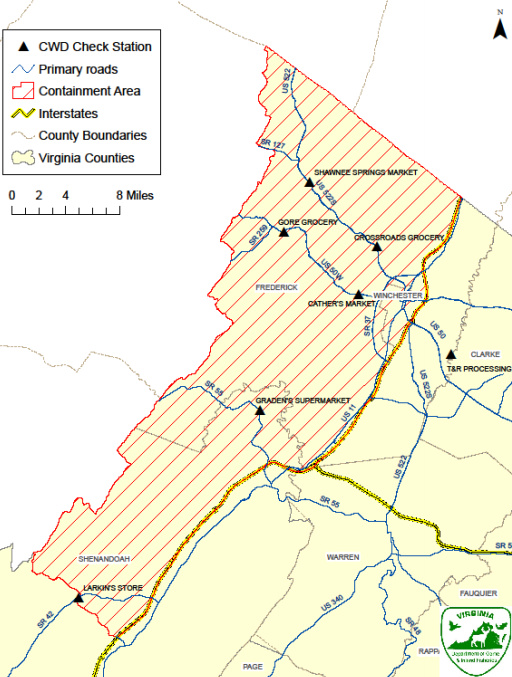

To contain the spread, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries quickly designated a portion of Frederick County as a Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) Containment Area. Deer, and parts of deer, can not be moved outside of the containment area. The state required deer in Frederick and Shenandoah County to be brought to sampling stations for testing.

Chronic Wasting Disease Containment Area, 2010-2014

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Chronic Wasting Disease Surveillance and Response Plan, 2014-2019 (Figure 5)

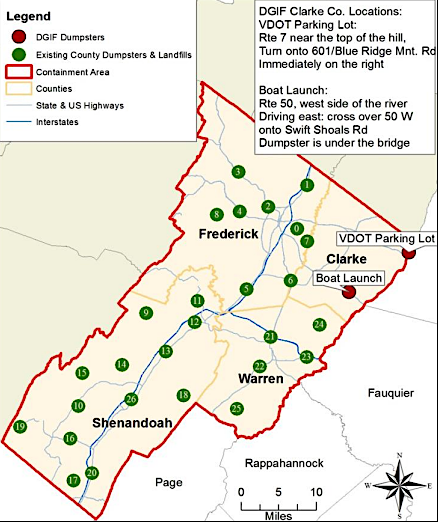

After the first infected deer was found in Shenandoah County, the containment area was expanded in 2014 to include all of Frederick, plus Clarke, Shenandoah, and Warren counties. Deer carcasses could not be moved outside of the Containment Area, but it was acceptable to process the carcass and then carry just the venison outside the boundary. The brain and spinal tissue was thought to be the most infectious component of the carcass, so the state wildlife agency encouraged hunters to bring carcasses to landfills or dumpsters for disposal.

landfills and dumpsters in northwestern Virginia that accepted deer carcasses (2019)

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Carcass Disposal Matters!

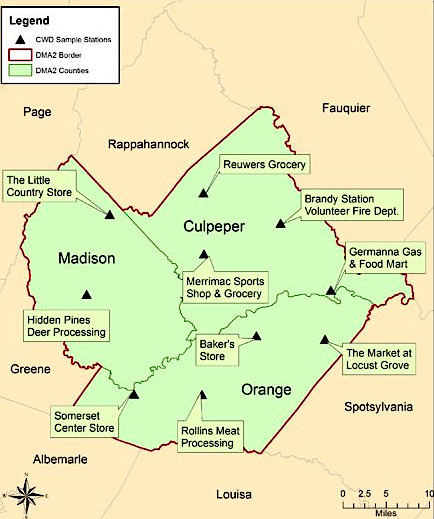

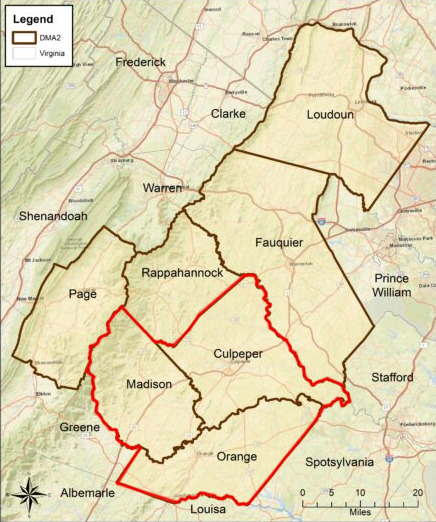

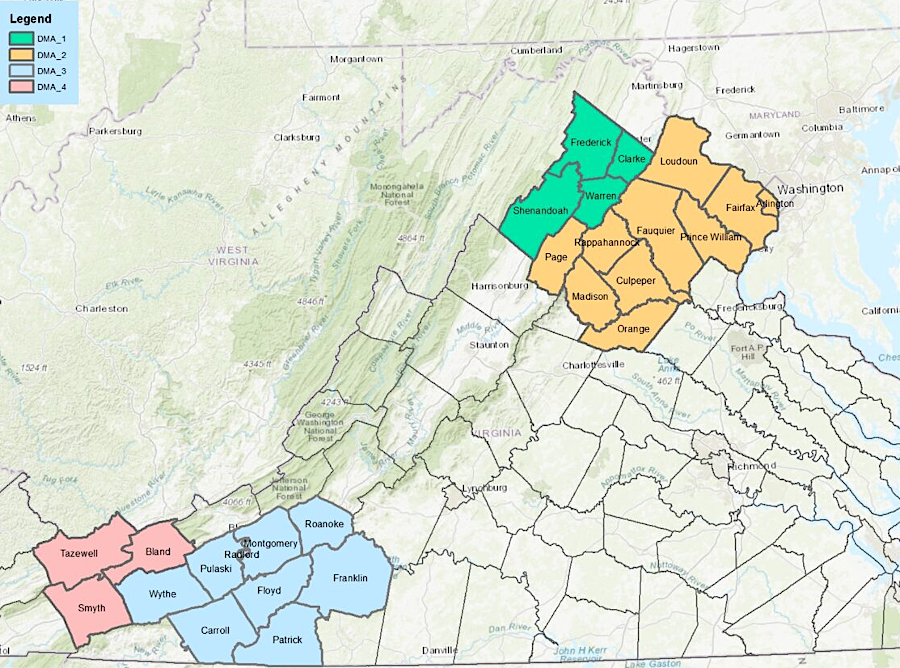

When the disease was identified in Culpeper County, the infected deer was 40 miles away from a previously-known location. The state agency recognized that containment was unlikely to succeed, so it reclassified the CWD Containment Area as CWD Disease Management Area 1 and designated a Disease Management Area 2 that included Orange, Culpeper, and Madison counties. Disease Management Area 2 was expanded to add Fauquier, Loudoun, Page, and Rappahannock counties.3

locations of hunter testing stations in the initial three-county Chronic Wasting Disease Containment Area 2

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, 2019 Mandatory Chronic Wasting Disease Testing in Disease Management Area 2

boundaries of Disease Containment Area 2 were expanded to include Fauquier, Loudoun, Page, and Rappahannock counties

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, What You Need to Know About Hunting in Disease Management Area 2

In 2020, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries announced that testing had identified infected deer in Clarke and Fauquier counties. Clarke was already within the boundaries of Disease Management Area 1. The deer in Fauquier County was found within two miles of the Disease Management Area 1 boundary. Later that year, after the agency changed its name to Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, a deer with the disease was identified in Loudoun County. The deer was killed by a hunter on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge, 10 miles from Clarke County and inside the expanded boundaries of Disease Management Area 2.4

The state agency focused its efforts on detecting infected deer outside Frederick County, since the presence there was already well documented, but Frederick County still remained the CWD "hotspot." Deer processors in northern Virginia worried that they might process what appeared to be a healthy deer but was actually an infected carcass, spreading the prions which caused Chronic Wasting Disease and potentially causing a human illness.

Chronic Wasting Disease spread outwards from Frederick County in an east/southeast direction

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Tracking Chronic Wasting Disease in Virginia

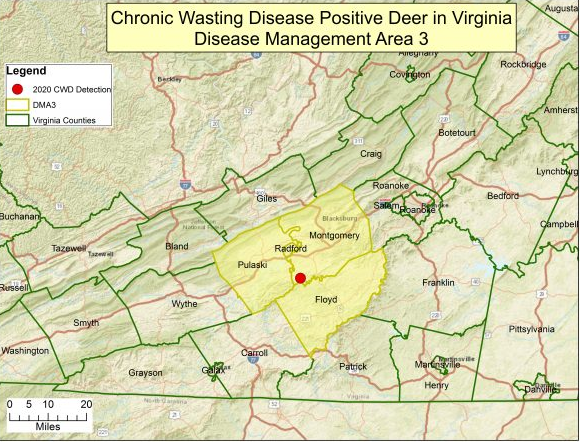

In 2021, the disease was identified in a deer from Montgomery County. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources quickly established Disease Management Area 3 encompassing Montgomery, Pulaski, and Floyd counties. Carroll County was added in 2022 after a CWD-positive deer was harvested in Floyd County.

Also, a 2022 sample submitted by a taxidermist in Fairfax County revealed that the disease had infected deer in the Vienna area. There were 47 positive cases in the 2022-23 season, and the only county outside a Deer Management Area to report such a case was Fairfax.5

Disease Management Area 3 was created in 2021, after discovering Chronic Wasting Disease in a deer from Montgomery County

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Tracking Chronic Wasting Disease in Virginia

By 2024, 15 years after the initial 2009 discovery in Frederick County, chronic wasting disease had been identified in 15 Virginia counties. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources established a fourth Disease Management Area including Bland, Smyth, and Tazewell counties, and expanded the number of counties in Disease Management Area 3.

In 2025, a deer with the disease was identified at Manassas National Battlefield Park in Prince William County.

Hunters have been allowed to carry meat from Disease Management Areas into other counties (typically to wherever they live). Transport of whole carcasses or brain/spinal tissue has been prohibited, but the meat is presumed to be safe to eat. Though chronic wasting disease is fatal to deer, the prions in consumed venison are not believed to initiate mad cow and Creuztfeld-Jakob diseases in humans.7

Disease Management Area 4, including Bland, Smyth, and Tazewell counties, was created in 2024

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Chronic Wasting Disease

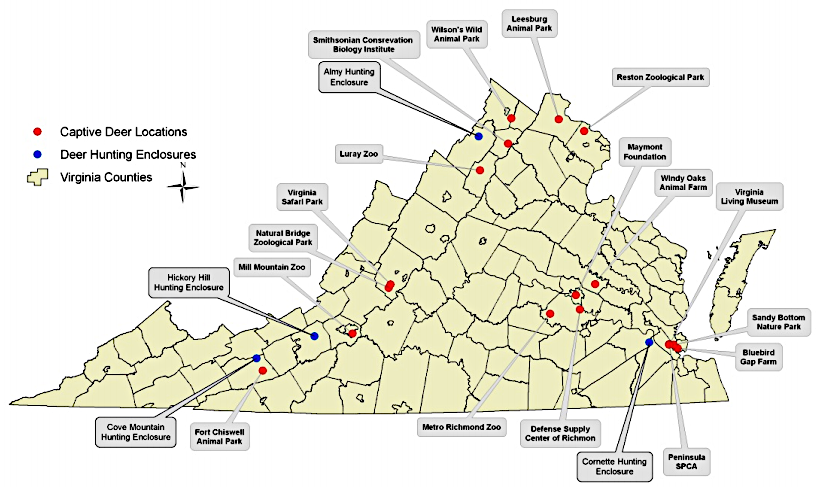

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources considers all areas with captive elk or deer ("cervids") to be at high risk for Chronic Wasting Disease. Before a moratorium in 2001, the state authorized four white-tailed deer hunting enclosures that are still in operation. In addition, the "Bellwood elk" have been at the Defense Supply Center Richmond since 1900, and various zoos, petting farms, and nature centers have cervids in captivity.8

where captive deer and elk are located in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Captive cervid facilities in Virginia (Figure 8)

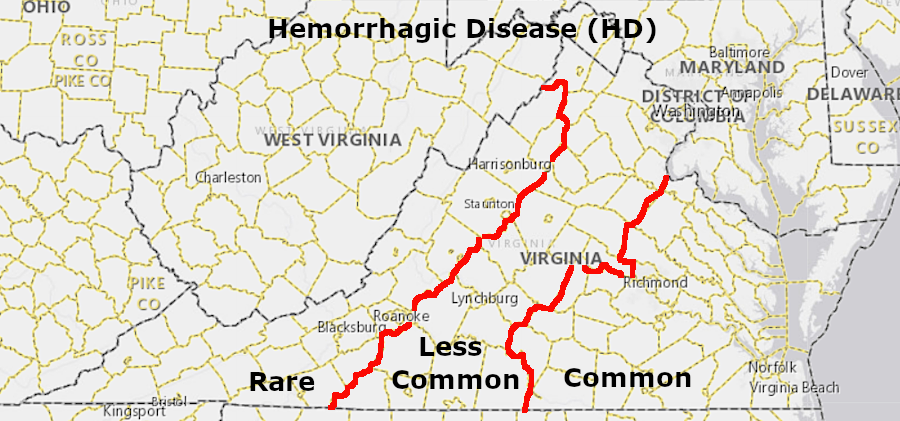

Chronic Wasting Disease is different from hemorrhagic disease (HD), which is caused by a virus transmitted via tiny biting midges. After mild winters and hot summers, massive numbers of gnats can multiply in mudflats during a drought. In 2014, about 50% of the deer between the Northern Neck and the North Carolina border became infected before the midges transmitting the virus were killed by frost.

Hemorrhagic disease is most common on the Coastal Plain. As of 2025, it was still rare west of the Blue Ridge, except in the northern part of the Shenandoah Valley (Frederick, Clark, and Warren counties).

hemorrhagic disease is most common on the Coastal Plain

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Hemorrhagic Disease (HD)

Deer suffering from hemorrhagic disease develop a high fever and act like they are intoxicated. Their heads "flop around" and they do not run away from people; some die from inflammation and fever. Deer that survive an infection often develop sloughing/splitting hooves.

Hemorrhagic disease is not transferable to humans. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources says the venison is safe to handle and eat, unless they develop secondary bacterial infections.

Outbreaks are most common in years with mild winters, hot summers, and a June drought. The disease is a common one in Virginia:9

Chronic Wasting Disease crossed from West Virginia into Frederick County in 2009, and then spread

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Tracking Chronic Wasting Disease in Virginia

hunter cooperation is essential in testing for Chronic Wasting Disease

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Tracking Chronic Wasting Disease in Virginia