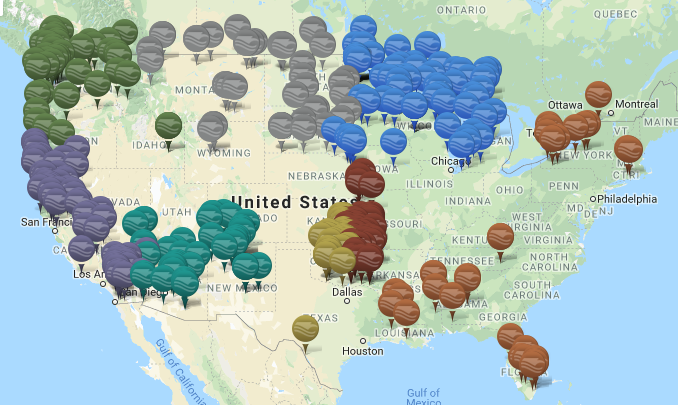

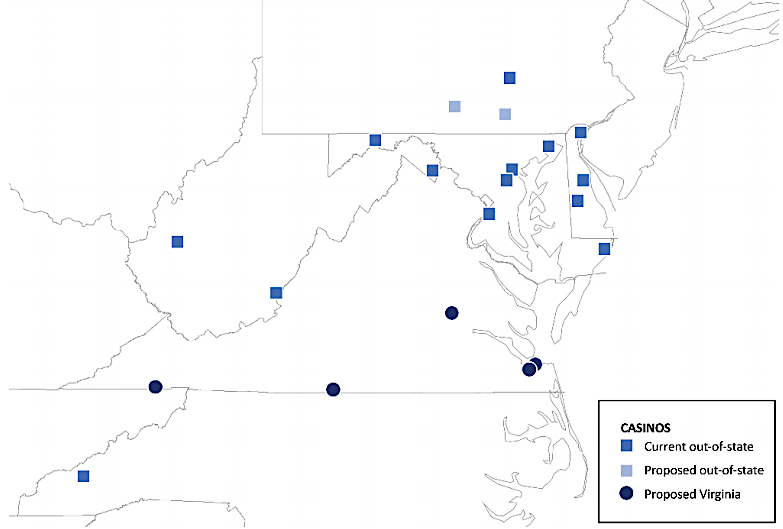

in 2018, there were no Native American gaming centers on the East Coast between Foxwoods Resort & Casino in Connecticut and Cherokee Tribal Bingo in North Carolina

Source: National Indian Gaming Commission, Map of Indian Gaming Locations

in 2018, there were no Native American gaming centers on the East Coast between Foxwoods Resort & Casino in Connecticut and Cherokee Tribal Bingo in North Carolina

Source: National Indian Gaming Commission, Map of Indian Gaming Locations

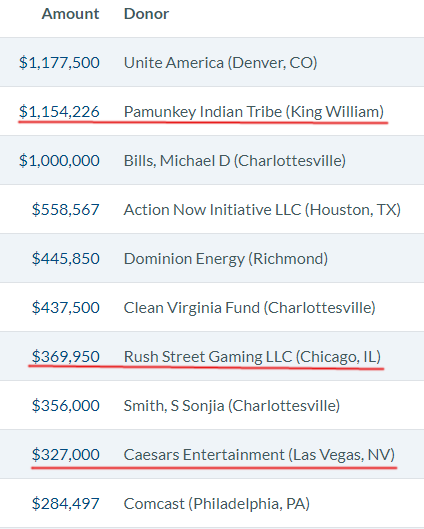

Federal recognition of the Pamunkey tribe in 2015 opened the door for the tribe to offer some form of gambling on the reservation, or on lands acquired later by the Pamunkey, under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. That led to the 2019 General Assembly ordering a study of casino gambling in Virginia, a precursor to anticipated approval in 2020. The 2019 law set criteria which limited a casino to just five cities - Norfolk, Portsmouth, Richmond, Danville, and Bristol. Only the Pamunkey tribe was authorized to open a casino in Richmond and Norfolk.

In 2015, the potential of the Pamunkey to open a casino was unique in Virginia. Six other Virginia tribes were Federally recognized by an act of Congress in 2018, but the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 prohibited those other six tribes from engaging in gaming. A section for each tribe stated:1

in 1776 the Fifth Virginia Convention, which took the great risk of declaring independence at the start of the American Revolution, sought to block gambling

Source: Library of Virginia, Resolution regarding gaming, 1776 June 25

The Pamunkey were recognized through the administrative procedures of the Department of the Interior, not through legislative action by the US Congress. Throughout the long recognition process, the tribe always retained the option of using the authority in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act to start Class II or Class III gaming operations. That risk was great enough for the MGM corporation, which operated the MGM National Harbor Resort and Casino in Maryland, to oppose Federal recognition of the Pamunkey.2

The US Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, once year after the US Supreme Court ruled in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians that states could not prohibit gambling on reservations of Federal-recognized tribes unless the state prohibited all forms of gambling. States with a lottery, or which authorized bingo, had to negotiate some deal with tribes that wanted to open casino-style operations.

When the Federal Bureau of Investigation sought to seize slot machines from the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation in 1992, tribal members surrounded the Federal agents and blocked the trucks with the slot machines from driving away. After that incident, governors recognized they had to negotiate deals with the tribes and authorize gambling on Native American reservations.

The law defined traditional behavior at tribal ceremonies as Class I gaming, including prizes for individuals and groups. Class II gaming included bingo and card games involving skill, such as poker. Class III gaming included slot machines and games of pure chance, such as craps, baccarat, and roulette wheels.

By creating three classes of gambling, Congress increased the leverage of both tribes and states.

If a state simply refused to bargain, the Secretary of the Interior was granted authority to approve Class II gaming operations. Under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, states have no authority to regulate or block Class II operations on lands held "in trust" for the tribe by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.3

Class II operations requiring some level of skill by the gambler, including bingo and poker, can generate substantial revenue. However, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act required tribes to get a Class III license before offering games involving pure chance without any level of skill, such as the pull-the-handle-and-see-if-you-won slot machines so common in Las Vegas. Class III gambling offered the potential for higher profits.

The Federal law required a state and tribe to negotiate a joint "compact" before a tribe could offer Class III games. State officials were given the power to block tribes from offering the more-lucrative Class III gambling opportunities until tribes agreed to some sort of deal. In exchange for state approval and the opportunity to provide a full gambling experience, tribes might bargain over where casinos will be located, and agree to share gambling profits with the state.

The law was also designed to allow tribes to sue states and force them to negotiate and ultimately agree to a compact authorizing a Class III license. The ability to force action by a sovereign state was blocked by a Supreme Court decision in 1966, but technology has offered ways to blur the lines between Class II games of skill and Class III games of chance.

Modern bingo machines can be almost indistinguishable from slot machines. Castle Hill Studios in Charlottesville, now Castle Hill Gaming, developed video bingo machines that technically required some form of skill on the part of the gambler while offering the equivalent experience of pulling the handle of a Las Vegas slot machine. Tribes willing to invest in high-tech equipment have regained some leverage in the negotiations.4

Castle Hill Gaming, based in Charlottesville, has created a wide range of Class II video bingo games

Source: Castle Him Gaming, The Best Games in Class II

Virginians have taken their gambling business out of state to Charles Town in West Virginia, the MGM casino at National Harbor in Maryland, or more-distant locations. West Virginia has five casinos, Maryland has six, Delaware has three, Pennsylvania has 12, not to mention Atlantic City and Las Vegas.

Starting in the 1990's, legislators from Norfolk and Portsmouth asked the General Assembly to authorize a riverboat casino. Over 50% of the land in Portsmouth is tax-exempt, and revenue from gaming could help fund city services. the General Assembly has consistently rejected proposals to allow gambling in Hampton Roads or create a Virginia Casino Gaming Commission.5

Federal recognition of the Pamunkey authorized a casino on lands owned by the Pamunkey, including property on I-64 outside the current boundaries of the reservation on Pamunkey Neck. Opening a casino with games of pure chance such as slot machines required the Bureau of Indian Affairs to take the property "in trust" for the tribe, and for the Virginia governor to sign a Tribal-State compact authorizing Class III gaming.6

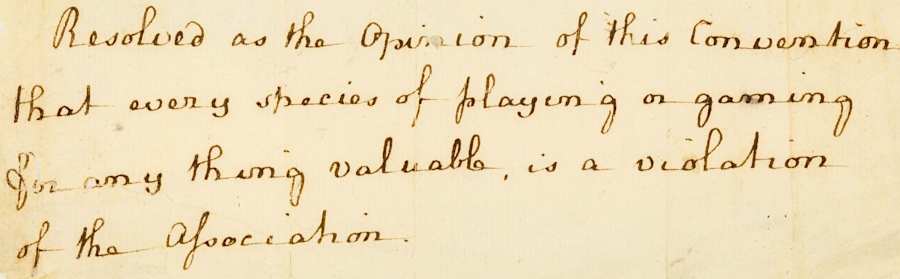

the National Indian Gaming Commission has defined the key steps for opening casinos with Class III gaming

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (Figure E-2)

The tribe did not expect customers to drive for almost an hour on narrow, two-lane roads from I-64 to the historic reservation site on Pamunkey Neck. The tribe first announced plans for a $700 million casino, hotel and spa elsewhere in eastern Virginia, working with private partners who would provide the needed investment capital. The Pamunkey anticipated they could work with the Middle Peninsula Planning District Council to find a site on territory that was formerly within Tsenacommacah, and where local governments would support economic development based on gambling.

The site would be designated as "trust" land and added to the reservation, even though it would not be adjacent to the current reservation on Pamunkey Neck. Once the tribe and state signed a compact establishing ground rules for revenue distribution, then slot machines, roulette wheels, and card games such as blackjack would be regulated by the National Indian Gaming Commission. The tribe might start with Class II gaming prior to the General Assembly approving a tribal-state compact, but the intent was to match the scale of the MGM National Harbor operation with its 4,000 employees.7

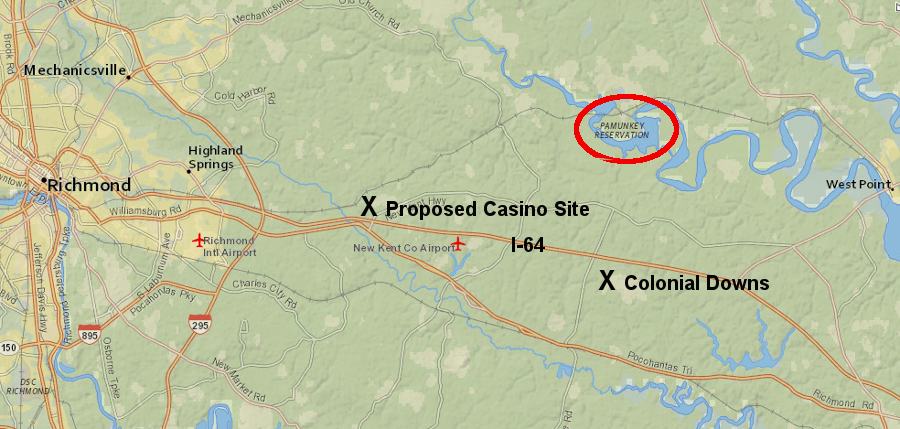

The Pamunkey and a billionaire who had become wealthy by selling video games to Native American casinos, venture capitalist Jon Yarbrough, announced in 2018 that he had purchased 610 acres at an I-64 interchange east of Richmond. He paid over $3 million for land that was in New Kent County, on the north side of Exit 205 and just east of the Chickahominy River.

The Pamunkey indicated they would consider locating a casino there, though there were still other locations being considered. Chief Robert Gray commented on the New Kent County land purchase:8

an Illinois-based video gaming operator purchased 600 acres along I-64 east of Richmond as a potential site for a Pamunkey-owned casino and resort

Source: Daily Press, Pamunkey Indian Tribe associates buy New Kent land for possible resort, casino site

A casino at the Exit 205 interchange would place a Pamunkey-based gambling center in direct competition with Colonial Downs, about 10 miles east on I-64 at Exit 214. Prior to the Pamunkey's announcement about their casino plans, the 2018 General Assembly had loosened restrictions on video gaming at the former racetrack and Off Track Betting parlors, by allowing "historical horse racing" machines that closely resembled slot machines.

Despite moral opposition to gambling by many voters, the General Assembly relies upon the Virginia Lottery to generate over $650 million annually by 2018. Legislators were willing to increase gambling opportunities in order to incentivize a new owner to re-open Colonial Downs in 2019. The new owner, Revolutionary Racing, had no association with the Pamunkey when it paid over $20 million to purchase the track. The demand for gambling opportunities was not unlimited. Authorizing a casino right after re-opening Colonial Downs obviously would reduce revenue from horse racing.9

The tribe did not commit to any project at the Exit 205 interchange when the land purchase was revealed. The Pamunkey bought an interest in the property at the Exit 205 interchange, but kept open the possibility that they might negotiate a deal to locate at some other site between Richmond and Hampton Roads. A partnership with the tribe to build a casino at Colonial Downs could have enabled Revolutionary Racing to offer far more gaming choices at the racetrack, but profits would have to be shared.10

As one commentator noted, even with expanded gambling on historical horse races, the racetrack is still far from the population center in Northern Virginia. Despite traffic, it is easier for a gambler living north of the Occoquan River to go across state lines to the Charles Town Racetrack and Hollywood Casino in West Virginia or to the full-scale casino opened by MGM at National Harbor in Maryland. Colonial Downs is also far from most Virginia horse farms, which send thoroughbreds to race at Charles Town, Laurel and Pimlico.11

two gambling centers have been proposed on I-64 east of Richmond, one by the Pamunkey tribe and one at the former Colonial Downs racetrack

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Wherever the Pamunkey casino and resort might be located, the political approval process required actions by Federal, state, and local officials.

New Kent County could have benefitted from a casino at either Colonial Downs or on the Pamunkey's nearby land. There could have been gambling at both sites, unless casino developers decided that only one site would be economical.

The preference of New Kent County officials and residents for gambling at Colonial Downs over a casino owned by the Pamunkey Tribe became clear when the county organized a public meeting in May, 2018. Racetrack officials discussed how they would reopen in 2019, with historical horse race wagering machines. No Pamunkey were invited to present their proposal. Instead, the county hired a law firm not associated with the tribe to discuss the regulatory process through which Native American gambling could be authorized.

News reports of the meeting noted:12

The tribe recognized that a casino at Exit 205 would meet resistance, and responded that it would consider other locations. Chief Robert Gray said the tribe would sign a revenue-sharing agreement with the state and whatever local jurisdiction in which it located, in order to mitigate the extra costs associated with the facility. He also noted:13

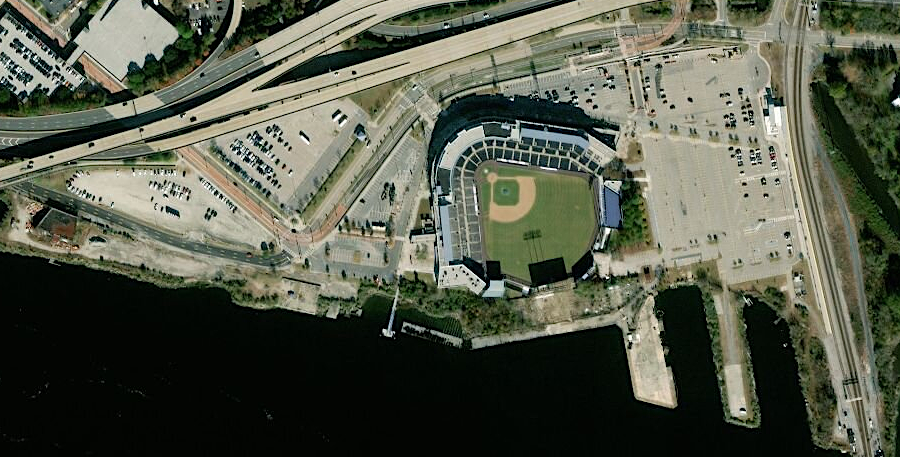

The preferred location was revealed in late 2018 to be a site in Norfolk, next to Harbor Park and the Amtrak station.

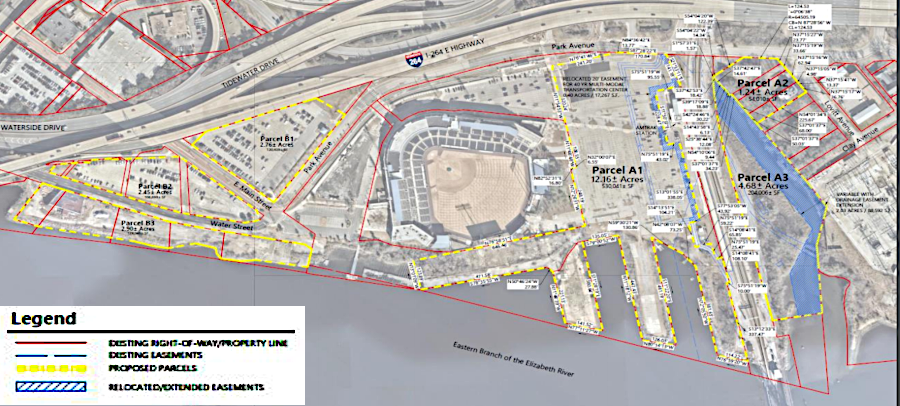

parking lots surrounding the Harbor Park baseball stadium would be replaced by the casino/hotel complex

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online and Norfolk City Council, Hotel & Resort Casino Update (September 10, 2019)

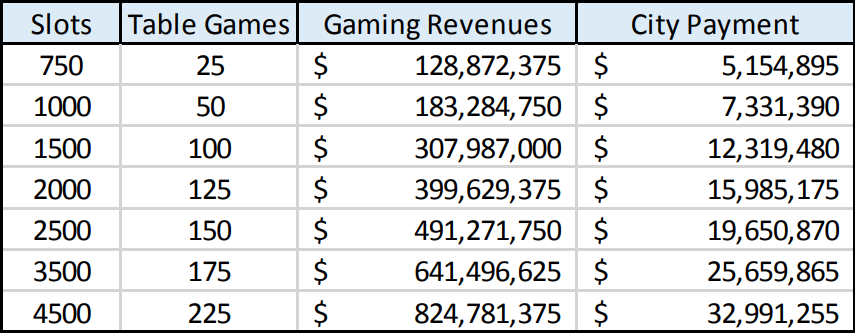

The tribe's financial backer, real estate developer Jon Yarbrough, proposed to purchase 13 acres between the baseball park and the Amtrak Station for $10 million. He would build a $700 million facility with up to 4,500 slot machines and 225 gaming tables, a 500-room resort hotel, up to five on-site restaurants, and a 750-seat entertainment facility. When completed, it would generate 3,500 jobs.

Yarbrough had gotten started in gambling while working at the NASA-Langley facility in Hampton, Virginia. When he returned to college, he had no room for his foosball table. He cut a deal with a local game room and placed it there, and then discovered how much income could be generated by customers paying just $0.25 per game. He bought more foosball tables and stationed them in fraternities, expanded with the Space Invaders video game, and eventually built an empire based on video slot machines in Indian casinos.

Norfolk officials viewed the proposed casino as a transformational economic development and revenue-generating project

Source: Norfolk City Council, Hotel & Resort Casino Update (September 10, 2019)

The Pamunkey proposal for Norfolk included no city incentives, and local officials viewed the project as "transformational" for the city.

the Pamunkey proposed building a high-rise resort hotel, as part of the casino package next to Harbor Park

Source: Norfolk City Council, Hotel & Resort Casino Update (September 10, 2019)

Once the Virginia General Assembly authorized a commercial casino, the tribe planned to pay standard taxes for food, hotel rooms, etc. The city initially expected to receive a minimum of $3 million in revenue annually, and up to $33 million.14

the lobbing/public affairs firm hired by the Pamunkey made clear that Norfolk would receive substantial revenue if the casino was completed

Source: All In for Norfolk Casino

If the 2020 General Assembly did not authorize a commercial casino, then the Pamunkey could rely upon the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and build a casino according to Federal law. The tribe could under Federal law offer Class II gambling opportunities requiring a certain level of skill, such as poker. Class III gambling, with all types of slot machines and table games, would require a compact between the tribe and the state.

The authority of the Pamunkey to build a casino next to the Harbor Park baseball stadium in Norfolk, based upon the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act separate from authorization of casino gambling by the 2020 General Assembly, would require convincing the Department of the Interior to take that parcel of land into trust for the tribe. To get the Federal agency to take that action, the Pamunkey would need to prove that the Norfolk area was part of its ancestral lands.

When the English colonists arrived in 1607, the area on the Elizabeth River was controlled by the Chesapeake tribe. The paramount chief, Powhatan, seized their territory around that time Jamestown was founded and added it to his paramount chiefdom, making it part of Tsenacommacah. Powhatan had been born into the Pamunkey tribe, so the claim to the Norfolk area was based on conquest of the Chesapeake tribe. The Pamunkey had traditionally lived along the Pamunkey River, so Norfolk was not near any of their ancestral towns.

The current Pamunkey chief supported the plan, saying "We don't say this is ours and no one else's." The previous Pamunkey chief, who had been ousted from his position in 2015, was an opponent of the casino proposal. He viewed it as an effort by a billionaire to use the tribe's historical status in Virginia as a social justice front, to prevent opposition to what otherwise would be a business deal with competition from other investors.

The former chief also was skeptical about the tribe's claimed association with Norfolk. He suggested that Pamunkey traders and representatives from Powhatan had paddled to the Elizabeth River territory, but the tribe had never settled there. The Virginian-Pilot reported:15

in 1607, the Pamunkey town of Powhatan was far from the proposed location of the tribe's casino (red X) in 2018

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

The Chesapeake tribe was disrupted and displaced during the colonial period, and the tribe no longer exists as a recognized group. The Nansemond tribe is the state-recognized Native American group living closest to the Elizabeth River now. When Virginia returned, in compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the parts of 64 Chesapeake skeletons which had been excavated at Great Neck in Virginia Beach, the remains were given to the Nansemond. The Nansemond, not the Pamunkey, reburied the bones of the Chesapeakes in First Landing State Park in 1997.

As soon as the Pamunkey proposed placing a casino in Norfolk, the Nansemond tribe objected. They had used a process for Federal recognition which was different than the administrative route used by the Pamunkey. The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 had granted formal Federal recognition to the Nansemond, but the law blocked the tribe from engaging in gambling. The Nansemond considered Norfolk to be within their historic territory, but lacked any option to offer gambling there.

Source: 13News Now, Nansemond Tribe defends its history as Pamunkey, Norfolk move forward with casino plans (September 27, 2019)

the lobbing/public affairs firm hired by the Pamunkey asserted that multiple tribes could claim historic rights to the land along the Elizabeth River

Source: All In for Norfolk Casino

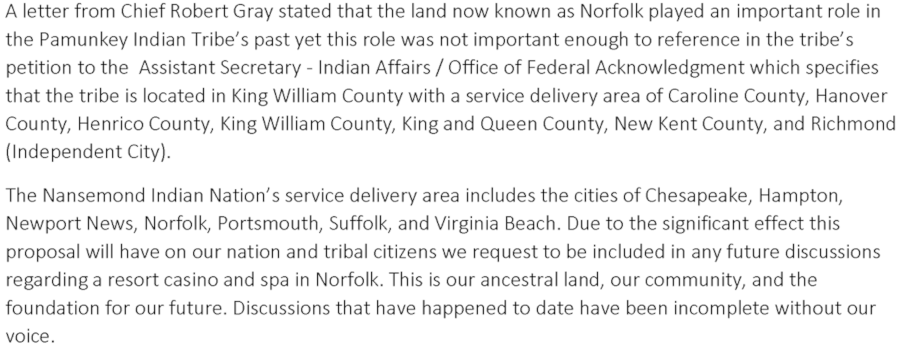

There was the potential for the Nansemond to acquire land in Norfolk and have the Federal government take that property into "trust" for the tribe, with a variety of uses other than gambling there. Only one tribe would be able to go through that process in Norfolk, however. When the Pamunkey plans for a casino at Harbor Park became public, the Nansemond chief sent a letter to the Norfolk mayor saying:16

the Nansemond objected to the Pamunkey claim in 2018 that Norfolk was part of their ancestral lands

Source: Facebook, Nansemond Indian Nation (December 19, 2018)

Indian gaming politics are especially complicated if the site is not located within the boundaries of the reservation of a Federal-recognized tribe. Rival casino operators can find state and Federal officials who will delay or stop the opening of a competitor.

In Connecticut, plans by the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot tribes to build an off-reservation casino were blocked by top officials in the Department of the Interior in 2017, apparently after lobbying pressure applied by competitor MGM Resorts International. The Bureau of Indian Affairs staff had endorsed the project, but final Federal approval was not granted.

MGM had a history of trying to block the Department of the Interior from granting Federal recognition to the Pamunkey prior to 2015. Protecting the marketing zone for MGM's casino at National Harbor provided enough economic incentive to lobby the Virginia General Assembly so no casino would be authorized in Northern Virginia, and to interfere with the Pamunkey's plans in Norfolk as well.

Other competitors, potentially including Colonial Downs, could have requested the Secretary of Interior from authorizing Class II gaming by the Pamunkey. Opponents of the Norfolk casino could cite the Carcieri v. Salazar decision of the US Supreme Court. The judges determined that land acquired by a tribe which was not "under federal jurisdiction" in 1934 may not be taken into trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the Indian Reorganization Act. Federal jurisdiction over the land is required before triggering the provisions of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and authorizing oversight by the National Indian Gaming Commission.

One objection to Norfolk's deal with the Pamunkey did come from the company that had recently redeveloped the Waterside District. That developer's contract for Waterside blocked the city from providing any financial incentives or grants for a competing major entertainment facility until October 2023. The Waterside developer's claim of a breach of its contract was based on Norfolk granting exclusive casino rights to the tribe, and exclusivity was described as a prohibited subsidy.

In 2024 the Virginia Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling that the clause in the lease was unenforceable. The Waterside developer could not claim exclusive rights to opening a casin0 in Norfolk.17

Promoters of new casinos always highlight projections of new employment and tax revenues. A 2015 report on potential casino gambling at Hampton Roads described how claims can be overstated. One problem is that expenditures at casinos by local residents will divert money that would otherwise be spent in the same geographic area for other goods and services.

A casino could end up redistributing dollars already being spent in Hampton Roads by local residents, such as reducing movie ticket sales in exchange for betting at the Pamunkey tables. If other local businesses shrink as the casino grows, there the claims of economic benefits for a casino will not offset economic losses. Promoters ignore that economic reality and emphasize only the new jobs in a casino, without acknowledging loss of existing jobs from restaurants, theaters, sports events, and various other entertainment sites. If all the money spent in a new casino came from local residents who previously had spent that money in local businesses, then the net economic impact of a casino would be zero.

Promoters claimed that Virginia casinos would generate new revenue primarily from customers who lived outside the state and traveled to the casino. It could also capture revenue now being spent by Virginians who travel out of state to gamble in west Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, etc. A location in Hampton Roads could attract out-of-state customers from North Carolina, but might not attract people who live north of Richmond and drive to the MGM National Harbor casino.

Like all real estate, value is based on location, location, location. If a casino can attract customers who do not already live in Hampton Roads, then the local economy will grow without diverting revenue from other businesses within the area.

The Pamunkey projected that there would be 6.7 million visits annually to their resort in Norfolk. Of that total, roughly 60% would come from parts of Virginia other than Norfolk itself. Visitors from Virginia Beach might simply shift spending to the casino from other places in Norfolk, but visitors from outside of Virginia and from more-distant places in Virginia (Richmond, Northern Virginia, Roanoke, etc.) would increase economic activity within the city.

Economists hired by the tribe claimed there would be:

- 1.4 million visitors from Norfolk

- 4.3 million from the rest of Virginia

- 1 million visitors from out of state

The 2015 State of the Region Report was not so optimistic. It noted:18

James V. Koch, the author of that report, was an economist who had served as president of Old Dominion University. He repeated his message that the economic benefits were being overstated in 2020, as the General Assembly neared approval of a bill authorizing casino gambling in five Virginia cities. He emphasized that the economic benefits assumed "zero expenditure displacement," that all consumers would spend money at casinos without altering their current spending habits. That assumption allowed the economic consultants to ignore impacts on existing businesses, which was an unrealistic approach:19

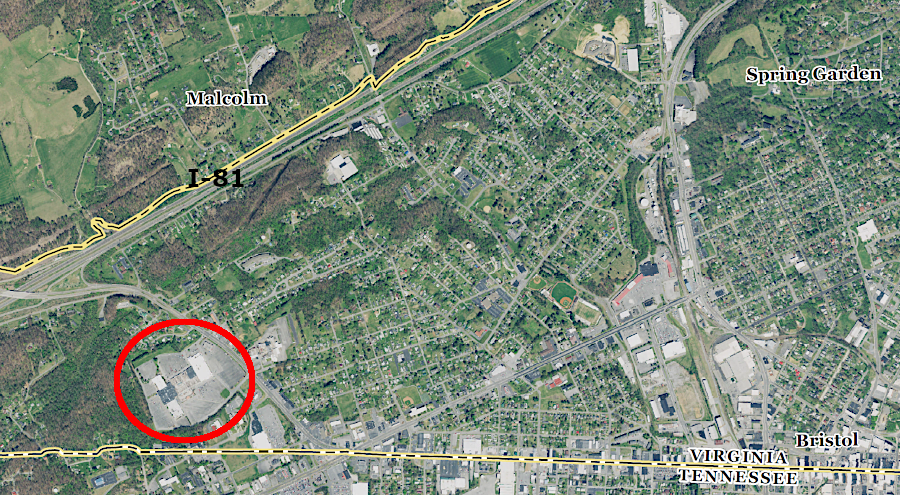

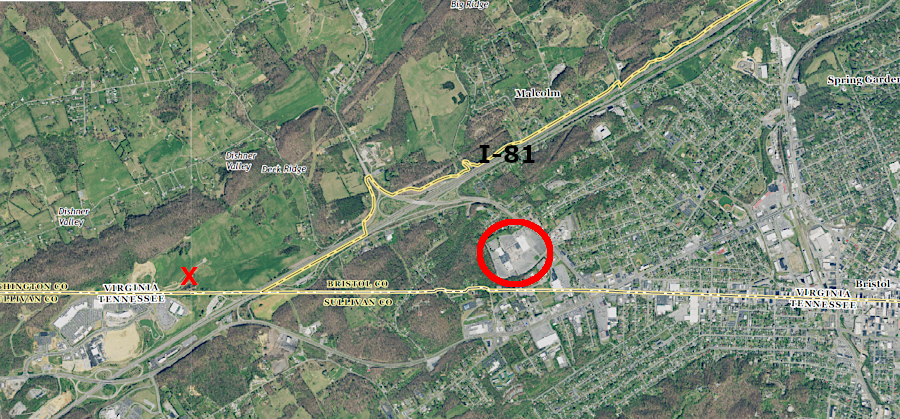

A group in Bristol had the same idea as the Pamunkey in 2018, and the Bristol Resort and Casino Team proposed a casino in a shuttered shopping mall near the Tennessee border. The casino would replace the Sears store in the now-closed mall, while the former Belk department store would be converted into a convention center. The hotel would be built in the rear parking lot.

The developers of the proposed casino/resort had to deal with the fact that the Virginia Department of Health had recently approved Dharma Pharmaceuticals locating its medical marijuana growing/processing/sales outlet at the same mall. Rather than offer both gambling and marijuana sales at the same site, the casino team proposed to move the medical marijuana facility.

Key conservative Republicans who represented the area in the General Assembly endorsed the proposal. Legislators saw a casino as a rare opportunity to create tourism-based jobs and increase tax revenue from visitors, but local religious leaders in the area organized opposition to a casino. At an ant-casino rally, one exclaimed:20

the shuttered Bristol Mall was approved for a medical marijuana facility while the Virginia General Assembly debated authorizing casinos

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol, TN 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle (2019)

The arguments of casino advocates in Bristol, which voted 70% for Donald Trump in 2016, matched those of the liberal Democratic state senator from Portsmouth, Louise Lucas. Starting in 2013, she had introduced legislation in every General Assembly to authorize casino gambling in the Elizabeth River city. Other legislators from the area had done the same in previous General Assembly sessions.21

After Bristol revealed its plans, Danville business leaders then proposed a casino in their area. That city hoped to draw customers from across the border in North Carolina, and to re-start a local economy that had been heavily damaged by the decline in manufacturing jobs since the 1980's.

In advance of the 2019 General Assembly, the city councils in Portsmouth, Bristol, and Danville voted to support casino gambling, despite opposition from some residents on moral grounds.

In November 2019, Danville voters also approved opening a Rosie's Gaming Emporium in the city, an Off-Track Betting parlor with satellite betting on live horse races and "slot machines" allowing betting on historical horse races. In 1987, 52% of the voters had opposed opening an Off-Track Betting parlor, but that ratio was reversed in 2019 and 52% of the voters were in support of Colonial Downs bringing state-authorized gambling to Danville.22

One member of the Danville City Council compared the potential economic stimulus of a full-scale casino to the recruitment of Amazon, which in 2018 chose to locate a portion of its second headquarters ("HQ2") in Arlington County:23

Bristol was a conservative area, politically and culturally. One of the casino opponents was a evangelical Baptist minister who commented:24

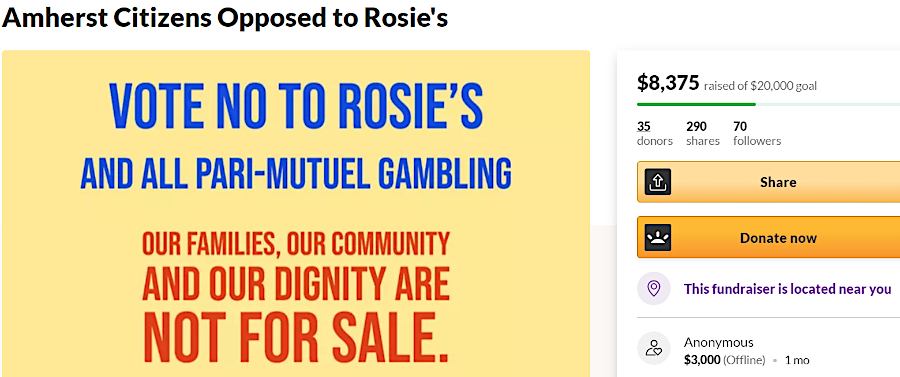

The Family Foundation of Virginia, a conservative organization, opposed the 2019 referendums in Danville and Dumfries that would permit Rosie's Gaming Emporiums there. The organization described the facilities that used historical horse racing machines as "miniature casinos filled with slot machines" and said:25

Danville officials saw a Rosie's Gaming Emporium as a precursor to permitting full-fledged casino gambling there, once state law allowed it, and were supportive.

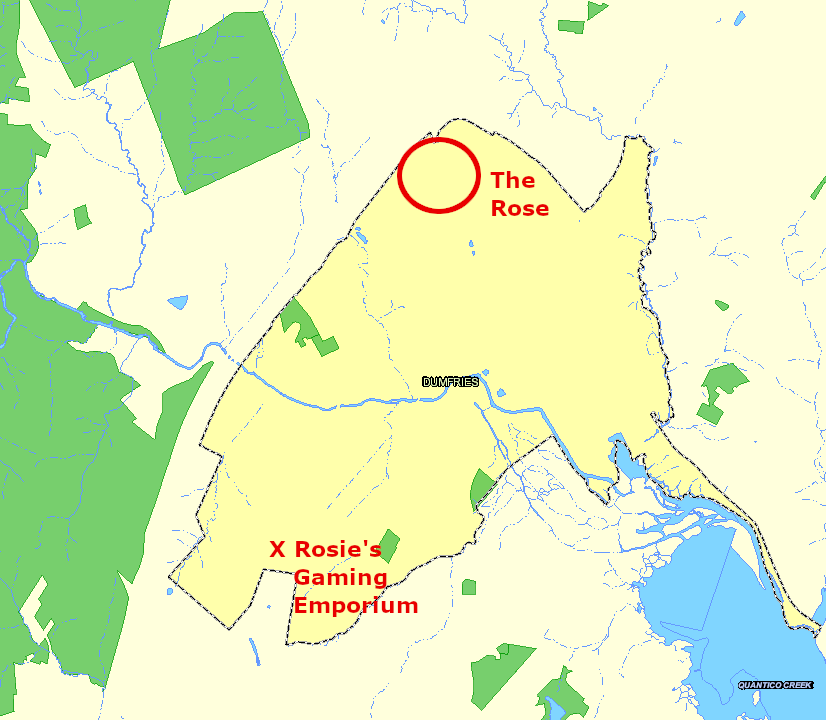

In Northern Virginia, where no casino was proposed for authorization, Colonial Downs was denied in its first effort to get a permit in Dumfries for a Rosie's Gaming Emporium. The company estimated it would pay $640,000 annually in tax revenue to the town, contribute an additional $100,000 to local charities, and pay its 150 workers a $15/hour minimum wage ($9/hour for tipped employees). It already had a lease agreement for space in the Triangle Shopping Plaza, but only three of the seven members of the Town Council supported the proposal.

Colonial Downs leased a vacant building for a Rosie's Gaming Emporium at Dumfries

The issue was brought back to town council, and approved in the second vote by a 4-3 margin. At the same time, the General Assembly was preparing to authorize an expansion from 150 historical horse racing machines to as much as 1,800 in Dumfries. Adding 150 machines would increase the town's tax revenue by $720,000 a year. If more machines were added, the town could double its tax revenue without any increase in the property tax rate.

When Colonial Downs opened the facility in January, 2021, it started with just 94 gaming machines spaced apart for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The $27 million investment in the Rosie's Gaming Emporium was expected to make profits off food as well as gaming. In the 50-seat restaurant, a bacon cheeseburger was priced at $14; chicken and BBQ sandwiches were priced at $10 each.

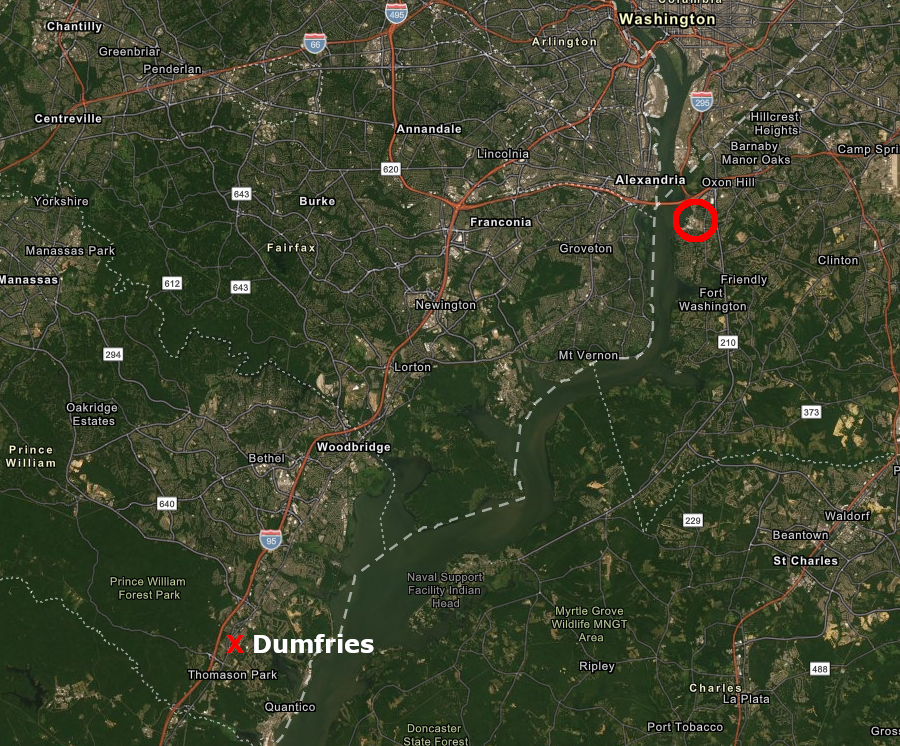

The mayor of Dumfries was a supporter. He said before the initial vote to approve gambling in his town:26

a Rosie's at Dumfries (red X) would compete with MGM National Harbor in Maryland (red circle)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The momentum from the Pamunkey proposal spread widely in 2019, with legislators recognizing that their areas could benefit if gambling restrictions were altered. No Native American tribe was associated with the Bristol, Danville, or Portsmouth proposals, but the Pamunkey would have competitors. One possibility was that greater competition/advertising for casino gambling at multiple sites in Virginia would expand the total number of customers, rather than reduce the number coming to a Pamunkey-owned casino.

casinos within a two-hour drive time from potential Virginia casino locations in 2019

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (Figure 1-1)

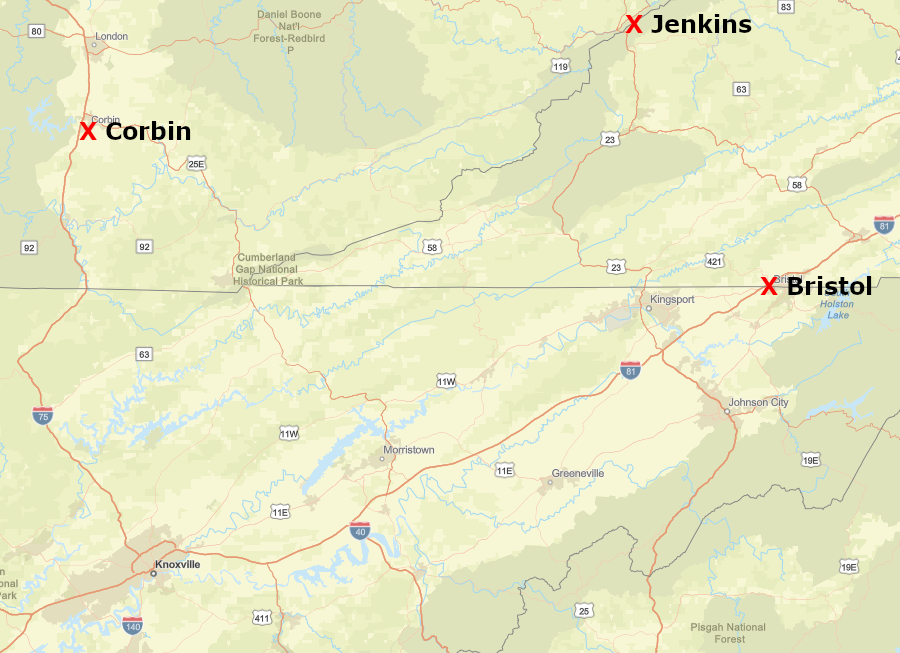

Advocates of the Bristol casino proposal recognized that the region could support only one casino. Bristol was not Las Vegas; business at a casino in Southwestern Virginia would come predominantly from people living within a one-day drive.

The casino planners feared that a legislature in an adjacent state would authorize casino gambling before Virginia, and the first casino would also be the last casino in the area. The Eastern Band of the Cherokee opened its first casino on the Qualla Boundary in 1997. It built a second casino in Murphy, North Carolina, in 2015. That facility was designed to attract customers from Atlanta, Chattanooga and Knoxville.

Another threat in 2019 came from Kentucky. Betting on horse races was already well-accepted in Kentucky. Bristol's leaders feared that the Virginia legislature would debate and delay casino approval while Kentucky's legislature authorized one, or perhaps more.

Churchill Downs planned to open an off-track gaming center in Corbin, Kentucky, while other developers proposed a full-scale facility in Jenkins, Kentucky. Economic change was the driver in Jenkins, as it was in Bristol. One investor in the proposed Raven Rock casino in Kentucky summarized the justification for expanded gambling:27

Jenkins was located west of Pine Mountain, a 90-minute drive from I-81. Corbin was a three-hour drive from Bristol. Casinos at those places might intercept customers planning an overnight vacation in Bristol Jenkins was unlikely to divert people from I-81 headed to the Bristol casino. Gamblers from Knoxville and East Tennessee could get to Corbin easily via I-75, so a full-scale casino there could diminish the economic activity at Bristol.

Jenkins might not draw gamblers off I-81, but Corbin could compete with Bristol by attracting gamblers from East Tennessee

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

If Tennessee authorized a casino, the competitive threat to Bristol would be even greater. Bristol itself was a low-population market, and the business model was based on attracting customers from nearby states with tighter restrictions on gaming operations. If the supply of casinos increased in Kentucky and Tennessee, then the customer base for a "unique opportunity" to play cards or slot machines at Bristol would shrink.

Building a casino at Bristol was literally a gamble. The boosters pushed hard for approval by the 2019 General Assembly, fearing further competition. One stated bluntly:28

a casino in Bristol could attract customers from 150 miles away

Source: Bristol Resort and Casino, Our Location

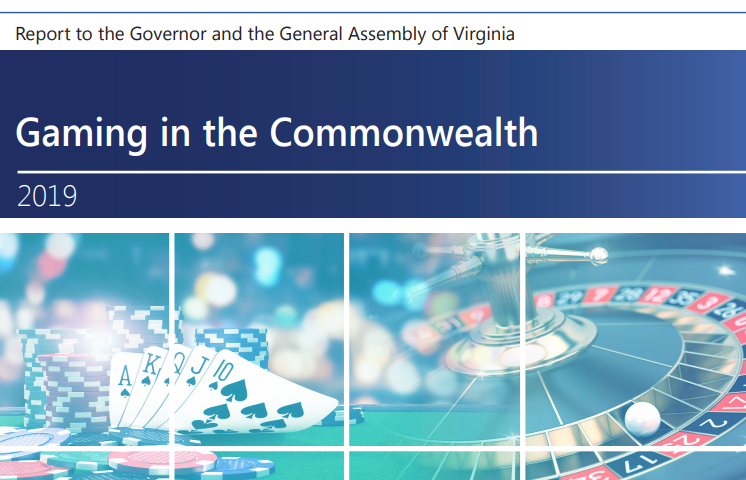

In 2019, the General Assembly approved a study of casino gambling, with the Virginia Lottery Board to be the state regulator. If the legislators gave final approval in 2020, then local referenda would have to pass before casino gambling could start in a locality. Only one casino would be allowed in each city.

The Pamunkey tribe had supported an earlier version of SB1126 that would have authorized casinos only in cities with at least 200,000 people. That constraint would have eliminated Portsmouth (with less than 100,000 people), blocking the possibility of a second $700 million casino, hotel and conference center in Hampton Roads that might compete with the Pamunkey's plans in Norfolk.

The committee modified the bill to specifically authorize Portsmouth, and also allowed the Pamunkey to build a casino in either Norfolk or Richmond. The state would receive 10% of the Pamunkey's revenue for authorizing Class III gaming.

State Senator Louise Lucas, a consistent advocate for authorizing a casino in her economically-stressed city of Portsmouth, exclaimed:29

Then the Senate Finance Committee applied the brakes and delayed action for a year. It required the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission to complete a study of the impacts of casino gambling, and no local referendum would be authorized unless the 2020 General Assembly approved. The 2019 session was a "short session" of just 47 days, and legislators were not comfortable that they understood the unintended consequences that might come with approval of casinos.

The effect of the delay was to give the Pamunkey an advantage. They could continue to prepare for a casino with Class II and potentially Class III gaming. Other investors in Portsmouth and Norfolk, as well as Danville and Bristol, lacked assurance for at least another year that their casino projects would be permitted.30

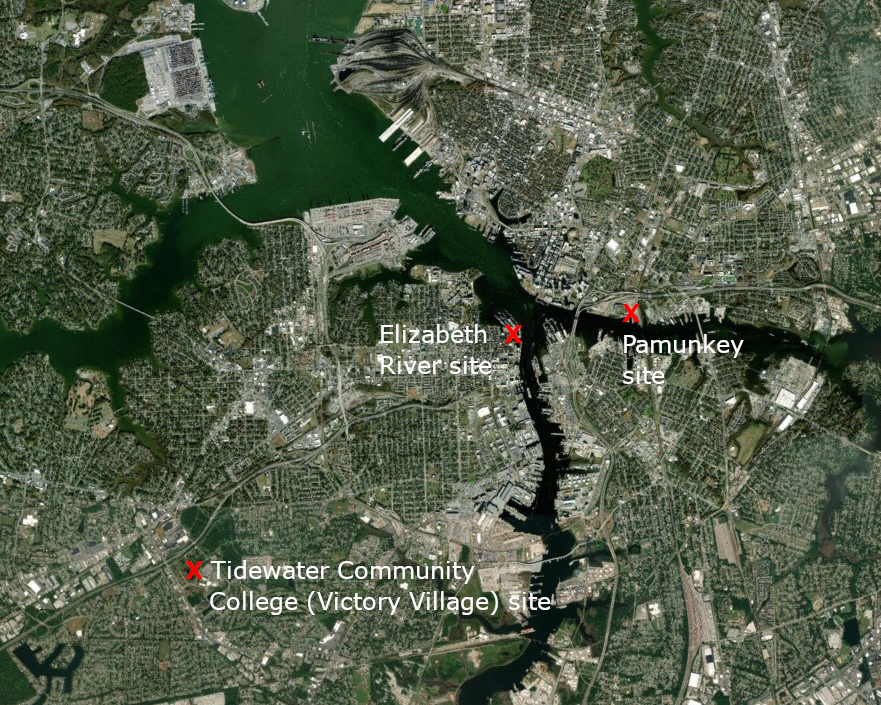

During the delay, Portsmouth re-examined its preferred location for a $700 million casino, hotel and conference center. It had originally supported a 7-acre site on the Elizabeth River waterfront where a former Holiday Inn had been torn down. City officials shifted their priority to a 50-acre parcel location closer to I-264.

The new site was closer to the interstate. It was adjacent to the Tidewater Community College campus, and had been planned for a town center called Victory Village. That project, also known as The Commons at Portsmouth, had not materialized and the developer resold the land back to the Portsmouth Economic Development Authority. The 50 acres could support development of a larger entertainment district with retail shops, restaurants, and meeting space.

in 2019, Portsmouth officials shifted the planned casino location from the Elizabeth River to a location closer to I-264

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Later in 2019, the city agreed to sell the site to a Chicago gaming firm, Rush Street Gaming, which had already built "regional casinos" in Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania. The sale price was for a minimum of $400,000/acre, totaling $10 million for the 50 acres. If the state did not authorize a casino resort, or if the company determined that was not an appropriate investment, the city anticipated that the site could still be developed as an entertainment district.

That location next to Tidewater Community College was also further away from the Harbor Park location in Norfolk, where the Pamunkey were considering building an equivalent casino complex. Investors doing due diligence might decide that the population in Hampton Roads was not large enough to fund two such facilities, but consultants for Portsmouth claimed that if both were built, Portsmouth would get 60% of the regional casino business. The percentages were based in part upon an assumption that Portsmouth would be authorized to have more gaming "devices" (i.e., slot machines) and tables for card games and other gambling.

One reason the casino was so attractive to Portsmouth officials was that it required no city-financed subsidies. An official with Rush Street Gaming commented:31

Rush Street Gaming planned to build a lake and pavilion, as well as buildings for gamblers at Rivers Casino Portsmouth

Source: Rivers Casino Portsmouth, Site Plan

That delay also gave opponents more time to organize. Del. Israel O'Quinn supported legislation in the House of Delegates that would lead to a casino in Bristol, and that led a challenger to run against him in 2019 for the 5th District seat in the Republican primary.

O'Quinn won the primary and then the general election in November. That month, the developers of the proposed Bristol Resort and Casino announced the planned casino operator would be a nationally-recognized company:32

Advocates of a casino in Danville argued that it could generate new business activity by attracting 75% of its visitors from North Carolina, including Greensboro, Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill, and Charlotte - so long as North Carolina did not authorize competing casino operations in Greensboro and Raleigh-Durham. The majority of the remaining visitors would come from other sites in Virginia, such as Lynchburg, Roanoke, and Martinsville.

North Carolina became very conscious of its lost economic opportunity and considered legalizing casino gambling outside of the Native American lands within the state. The North Carolina General Assembly debated authorizing casinos in 2023, delaying approval of the state budget by three months, before rejecting a proposal to authorize four new casinos and 50,000 video lottery terminals.

The Catawba Indian Nation purchased land on I-85 near Kings Mountain, close to the South Carolina border. The property was placed in trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and a temporary gaming facility opened in 2021. The Two Kings Casino there, a $1 billion project, is scheduled to open in

However, a local member of the General Assembly said that the city was being "used" by those seeking a casino elsewhere. State Senator Bill Stanley claimed Danville was included in the 2019 proposed legislation only to get the General Assembly to authorize gambling at Bristol and Portsmouth. He expressed his opposition in part by saying:33

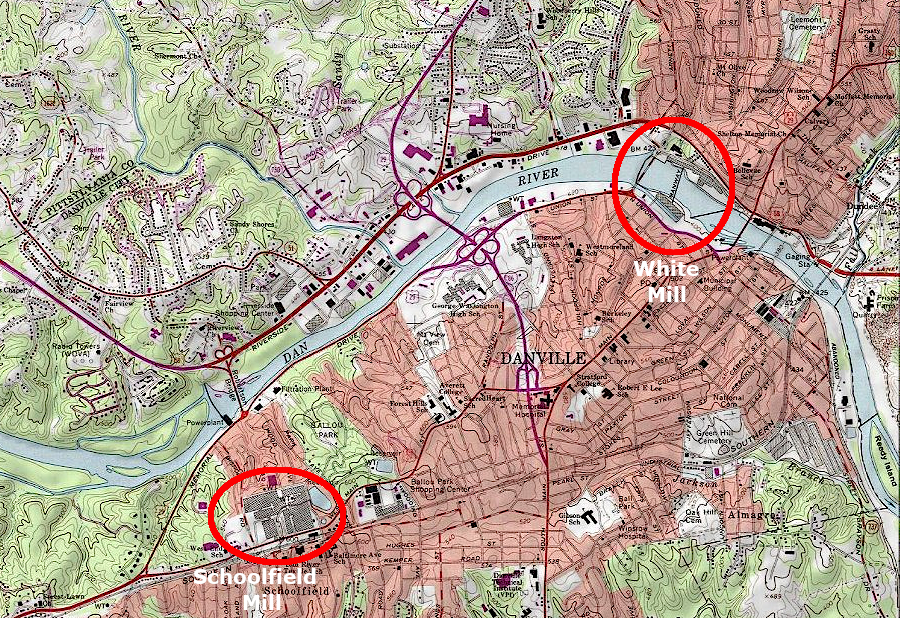

In anticipation of a 2020 local voter referendum which would authorize a casino, Danville studied the potential for a casino at four locations.

One was the White Mill building, formerly a key factory for the Dan River Inc. textile operations. The Danville Industrial Development Authority had purchased the vacant building in 2017 for $3 million. It had agreed to sell it for the same price to a company that renovates historic buildings and gets them back on the tax rolls, but ended up proposing it as a casino location. The Industrial Development Authority also owned the Schoolfield industrial site on West Main Street, once the home of housing for Dan River Mills workers s well as mill operations.

Along with White Mill, consultants hired by the city assessed the impact of a casino at the Schoolfield site, the Piedmont Drive retail corridor, and an unnamed location. The last of the four locations was not advertised to avoid biasing the decisions of potential casino developers. The consultants evaluated development in Danville of both a resort scale casino with 2,500 slot machines, 100 table games, and 325 hotel rooms and a smaller project with 1,200 slot machines, 60 table games, and 225 hotel rooms.

After hearing the consultants' report, city officials advertised a Request for Proposals for a private operator to develop a casino. The company could propose two locations, but one had to be either the White Mill or the Schoolfield site owned by the Industrial Development Authority.

Danville ended up receiving seven proposals from competitors. No other city created the opportunity for open competition. Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Bristol negotiated deals directly with just one casino operator, while Richmond allowed the Pamunkey and two other companies to discuss proposals.34

two former mill sites owned by the Danville Industrial Development Authority were identified as potential locations for a casino

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Norfolk accelerated its potential for getting the state's first casino in September, 2019. It negotiated a deal with the Pamunkey to sell land next to Harbor Park for the proposed hotel, restaurants, and entertainment venue featuring either Class 2 or Class 3 gaming. Just two weeks after releasing the details for public review, the Norfolk City Council voted 7-1 to give the tribe a five-year option to buy 13 acres west of the stadium for $10 million.

The one "no" vote said the deal was too quick, since the state study on gambling would not be completed for another two months and Norfolk did no independent study of the claimed impacts of the casino. The tribe could build a hotel with just 150 rather than 500 rooms, install just 750 rather than 2,000 slot machines, and provide just 25 rather than 225 table games. However, the tribe's payment to the city must be at least $3 million, whatever the size of the casino complex.

Among the speakers objecting to the quick sale at the City Council meeting were representatives of the Nansemond tribe. They were unsuccessful in getting the city to examine which tribe had legitimate historical claims to the territory where the casino was proposed. The Pamunkey chief asserted broad ownership by the Pamunkey throughout Tidewater, and also described Powhatan's paramount chiefdom as a "confederacy":35

The Pamunkey claim that Norfolk was within their tribe's historical territory is an issue would have to be addressed by the US Department of the Interior, if that Federal agency decided the Harbor Park parcel could be added to the Pamunkey reservation. Incorporating the parcel within the reservation would make activities exempt from state and local taxes, except what the Pamunkey negotiate to pay in order to get a Class 3 gaming license.36

After the quick approval of the land sale by the Norfolk City Council, a citizen's group started collecting signatures on a petition to block the action. Under the city charter, they could force a referendum if they collected signatures from at least 4,000 qualified city voters within 30 days of the city council's decision.

At the same time, the lobbying/public affairs company hired by the Pamunkey launched a pro-casino website, "All In for Norfolk Casino." It pretended to be a local effort unrelated to the Pamunkey tribe, but the local newspaper quickly identified that it was an artificial "astroturf" initiative by the Richmond-based firm Capital Results rather than an authentic grass-roots effort from Norfolk residents.

The initial purpose was clear - the website highlighted how people who had signed the petition for a referendum could withdraw their name. The effort succeeded - the petitioners failed to gather enough signatures to trigger a referendum. They were about 10% short of the required 4,000 signatures.

The anti-casino group then took advantage of a provision in the city charter to force another vote by City Council on the land sale, once 1,250 registered voters signed a petition for that action. The group collected 3,403 notarized signatures on Election Day, November 5, 2019. City council reacted by forming a Mayor’s Committee on Gaming, but the process did not increase citizen confidence that the issue would be reconsidered. The council created the committee at a meeting without announcing its plans or even placing the item on the official agenda circulated in advance.

It was obvious that the Norfolk City Council would re-affirm its earlier 7-1 decision, but the process to force a re-vote then gave the anti-casino group a new nine-month window to collect the 4,000 signatures required to force a citywide referendum.

Downtown restaurants were among the opponents of the casino. They feared that local customers would redirect their spending to the food facilities at the casino, and also hire away the waitstaff, cooks, and other workers needed by the downtown restaurants. Economic activity might increase overall if a casino was developed at Harbor Park, but the co-chair of the Downtown Norfolk Restaurant Association said:37

the pro-casino website was designed in part to block the referendum which might undo the City Council's land sale to the Pamunkey

Source: All In for Norfolk Casino

As anti-casino forces mobilized in Norfolk, the Hampton City Council voted to request that the General Assembly authorize a casino in that city on the Peninsula. That would expand legal gambling opportunities in a city that had just opened a Rosie's Gaming Emporium, a Off-Track Betting facility tied to the Colonial Downs racetrack in New Kent County, with 700 electronic gaming machines.

Mayor Donnie Tuck said in support of a casino in Hampton:38

Norfolk officials assumed that competition from a casino in Richmond would be healthy, but worried that a casino in nearby Hampton or Portsmouth might limit the economic benefits in Norfolk. They sought to position Norfolk as the prime location, hoping to deter investors from financing a competing casino in Hampton Roads.

Another concern was the lack of available land for creating mixed-use developments within walking distance of the proposed casino at Harbor Park, which would limit the opportunity to create a "Harbor Village" where casino customers made other purchases. A consultant warned that some cities had seen minimal revitalization of properties near their casinos:39

Throughout 2019, as officials debated legalizing casinos in Virginia, Georgia-based software maker Pace-O-Matic took advantage of the provision in state law that defines gambling based on the role of a player's skill. If there is any element of skill in whether a reward is authorized by a machine, then a player is not gambling on a slot machine where results are determined 100% by chance. For example, of a screen displays assorted pictures and the player has to identify a pattern, then skill is involved. Players must hit a second button within a fixed timeframe to claim their reward; that is proof of the pattern recognition and memory skills involved.

The Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority determined in 2017 that a facility's license to sell alcohol would not be at risk if Pace-O-Matic's skill-based entertainment machines known as Queen of Virginia were installed.

At the start of 2019, there were 500 vendors with skill-based entertainment machines. During the year, Queen of Virginia worked with 50 entertainment companies and, before the year was over, had placed 6,000 machines in 2,500 bars/restaurants, convenience stores, and other businesses with an ABC license. The company claimed that machines of its competitors, including Gracie Technologies and Banilla, had not received approval by the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority - and sought to have local police require their removal as illegal gambling devices. It even reported to police that a business using machines from a rival company was a "mini casino" operating illegally.

In each local jurisdiction, the commonwealth’s attorney had the option to define if the machines were legal. In June 2019, the commonwealth’s attorney in Charlottesville was the first to order the removal of gaming machines there.

The "grey machines" were installed in 10,000 stores by late 2019, many where Virginia Lottery tickets were sold. Lottery officials predicted a decline of $138 million in sales and a loss of $40 million in state profits. That created greater interest among members of the General Assembly in legalizing more forms of gambling that could generate tax revenue for school funding.

The Secretary of Finance reported a 28% drop in Virginia Lottery sales for October, 2019. His message for the General Assembly that would meet in January was clear:40

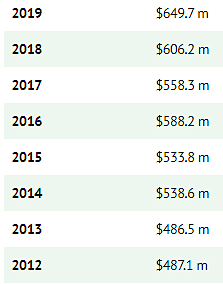

a predicted decline in previously-climbing Virginia Lottery profits spurred interest in legalizing other gambling that could be taxed

Source: Virginia Lottery, Giving Back to Virginia Public Schools

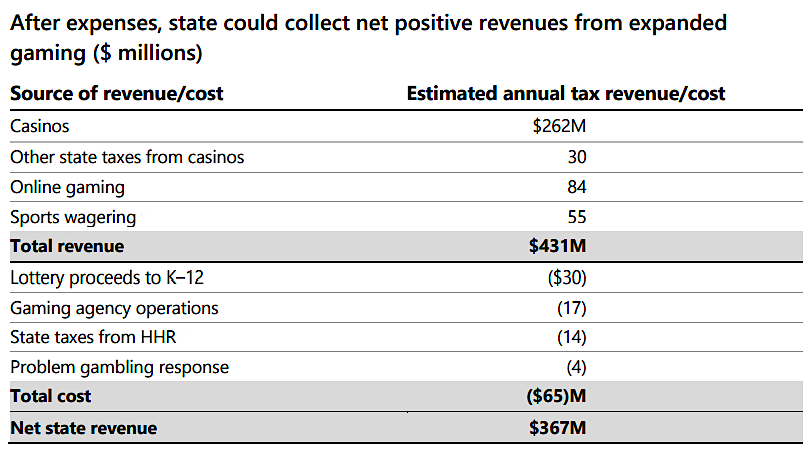

Authorizing casinos in Portsmouth, Norfolk, Richmond, Bristol and Danville could generate over $250 million/year in revenue for the state by 2025, according to a November 2019 report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission. Authorizing a sixth casino in Northern Virginia would generate another $150 million/year. The report assumed the General Assembly would set a 27% tax rate. Changing state laws to permit sports betting and online casino gaming, as well as casinos, could add another $100 million/year in revenue.

There were offsets to the new tax revenue that would be stimulated by the legalization of casino gambling. A program to address gambling addiction could cost $2-6 million annually.

Gamblers would bet 45% less on the historical horse racing machines at Colonial Downs and in Rosie's Gaming Emporiums, reducing the state tax revenue from those machines. The Virginia Lottery, a state-run gambling program which had been generating $600 million annually before skill-based entertainment machines became common in 2019, would generate $30 million less each year if customers could go to legal casinos. Bingo games and other local charitable gaming operations would see a 4% decline in revenue, primarily in the five markets where casinos would be operating.41

the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission projected five casinos would generate over $250 million in state gaming tax revenue

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (p.ii)

legalizing casinos would generate a net revenue increase that General Assembly legislators could appropriate or use to offset existing taxes (HHR=historical horse racing)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (p.vi)

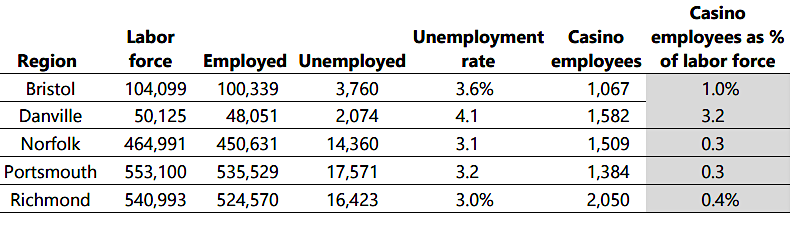

The state agency estimated that each casino would employ at least 1,000 people. Roughly half of the casino-related jobs would be low-skill and low-wage; the projected median wage of $33,000 would be lower than average in Portsmouth, Norfolk, Richmond, Bristol and Danville. A casino in Northern Virginia, with its larger market, could create an additional 3,200 jobs there.

estimated casino employment as a proportion of labor force for five proposed casino localities

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (p.ii)

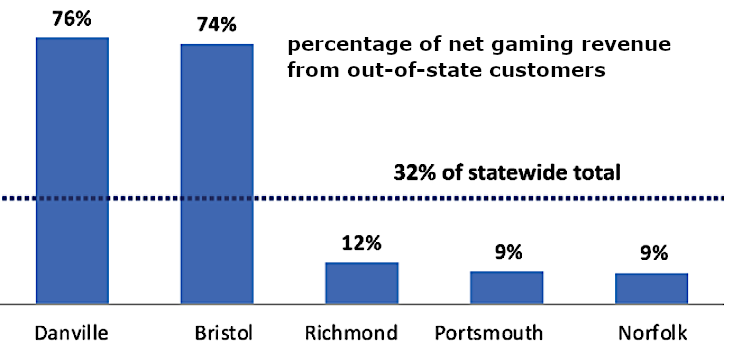

One-third of customers were predicted to come from outside of Virginia, but the vast majority of that business would be concentrated on the two casinos near the North Carolina state line because less than 10% of customers drive more than two hours to gamble. The competition at Harrah's in Cherokee, North Carolina, Mardi Gras Casino near Charleston, West Virginia and the Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia were at least a three hour drive from Bristol.

The Danville and Bristol casinos would be viable despite their small local populations, so long as neighboring states continued to limit casino gambling:42

Danville and Bristol would be most dependent upon out-of-state customers

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Gaming in the Commonwealth (Figure 2-2)

The proposal for the Pamunkey casino in Norfolk was scaled back in December 2019, after city staff completed an economic analysis independent from the studies submitted earlier by the tribe. The revisions came after opponents in Norfolk had gathered enough signatures to force a re-vote by City Council.

The new economic analysis indicated that there was not sufficient demand to construct a $700 million complex equivalent to the MGM National Harbor casino and resort hotel in Maryland. The city's analysis identified a potential for a $375 million complex, while the gaming study produced by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission considered a $300 million facility. The smaller facility would create 1,700 rather than 3,500 jobs. It would generate $6.4 million annually in tax revenues for Norfolk, far below the $33 million in the most-optimistic early projection by the tribe's consultants.

The Pamunkey responded to a request from Norfolk officials, and agreed to abandon plans to put 13 acres just west of the Harbor Park baseball stadium into trust and open a tribal casino. They would focus on a commercial casino, with revenue sharing negotiated between the tribal and state officials. In January, 2020 tribal and city officials signed an option for the Pamunkey to purchase the 13 acres to construct the Pamunkey Resort & Casino, if the General Assembly authorized casino gambling there.43

The reassessment of the casino potential in Norfolk happened prior to the opening of the 2020 General Assembly session which could authorize casino gambling in Virginia. The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission study released a month earlier had assessed the economic viability of casinos with a state tax rate of 27%. If the legislators adopted a lower tax rate, then casino developers might not be incentivized to invest more and build larger facilities, because the size of the customer base shaped how big a casino complex could be justified more than the tax rate. However, a lower tax rate could incentivize construction of casinos in more locations. A tax rate lower than 27% could help both Portsmouth and Norfolk find financing for two casinos on opposite sides of the Elizabeth River.

Taxes could also be imposed at different rates on different aspects of casino operations. One of the authors of the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission study noted that Pennsylvania's tax rate on slot machine revenue was 55%, but just 16% on revenue from gaming tables:44

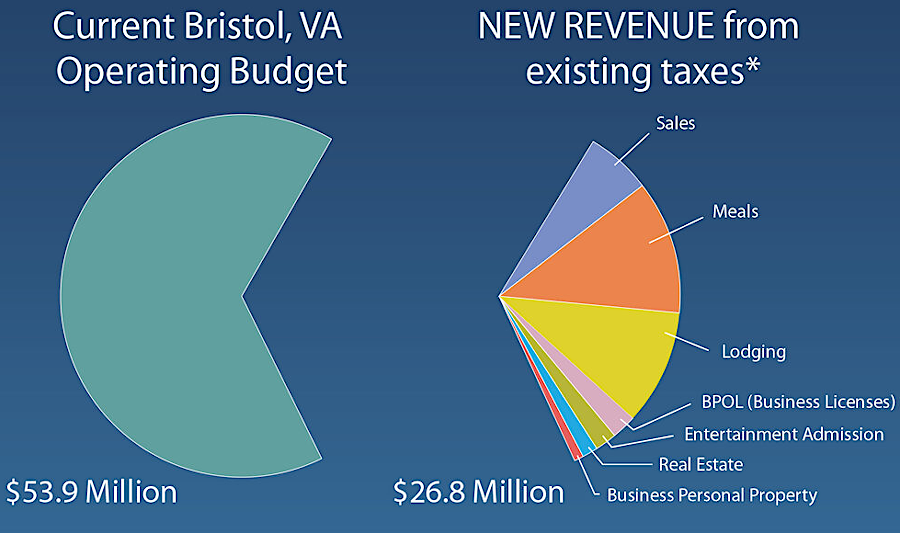

Those who proposed the Bristol casino argued that the state tax rate would be a major factor in their willingness to invest, and that the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission had miscalculate the economic benefits. The leader of the casino team suggested that a state tax rate of 9-12% rather than 27% might cause them to build a 600-room hotel rather than a 200-room project. The state report had focused on potential state tax revenue, but a full-scale casino/resort/hotel in Bristol might generate local taxes equal to 50% of the city’s current general fund budget.

The economic basis for the Bristol casino was to stimulate development of an entertainment resort, with the reputation of Hard Rock as a major draw. The plan was to use the casino as "the nuclear engine that makes people come here" and create a destination resort with entertainment, concerts, restaurants, and all the amenities offered by Hard Rock. 50 retail stores and space for sports betting were also planned.45

before the November 2020 referendum, the Hard Rock Bristol Casino and Resort claimed it could attract visitors from as far away as Atlanta and even Dallas

Source: Bristol Casino Resort

The business opportunity for a casino near Bristol was clear enough to attract a competing proposal in January, 2020. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians proposed to build a casino, 15,000-seat amphitheater, and hotel with an indoor waterpark to create a gambling-centered resort on the Virginia-Tennessee border. The Native American tribe already operated two casinos/resorts in North Carolina.

The proposed location was on a 350-acre parcel just north of The Pinnacle shopping center in Tennessee, behind the Bass Pro Shops store. It had to be across the state line in Virginia, since Tennessee was not proposing to authorize casino gambling - yet. The site was also in Washington County, outside the city limits of Bristol.

in 2020, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians proposed to build a casino, 15,000-seat amphitheater, and hotel just north of the Tennessee-Virginia line

Source: GoogleMaps

The casino developer working with the Cherokee had a history of competing with Bristol since 2012. The city built The Falls retail complex at Exit 5 on I-81. The developers of The Pinnacle began several years earlier, constructing their project just south of the Tennessee-Virginia border. Bristol was an economically-stressed city in part because the Falls had not generated as much revenue as planned, largely due to competition from The Pinnacle.

Developers of The Pinnacle had proposed an entertainment complex at that location in 2016. Washington County officials planned to use a special tax on admissions to finance its projected 50% share to build a new road for access. The county was willing to pay $13 million, and expected the Virginia Department of Transportation to pay the other half.

in 2016, developers of The Pinnacle proposed an entertainment center across the state line in Virginia

Source: Johnson Commercial Development, Plans to build entertainment venue, sports complex behind The Pinnacle move forward

That part of Southwestern Virginia was well within the traditional territory of the Cherokee, before colonists displaced them after the French and Indian War. The tribe initially rejected the possibility that the proposed site might be taken into trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, allowing Class III gaming through a Federal approval process. Since the Seminole Tribe of Florida had acquired the Hard Rock brand in 2007, the competition was between two separate tribes.

Bristol officials had chosen to work with one business group whose leaders were well known in the local community, and whose casino/resort would be located within the boundaries of the city rather than in Washington County. Bristol's leaders were not supportive of a different group of investors offering a different proposition in a different jurisdiction.

The city manager of Bristol claimed that a casino in Washington County was not authorized under the legislation already passed by the General Assembly, which identified only five sites for economically distressed communities. He made clear immediately that the competitive alternative to the Hard Rock casino/resort proposal was not welcomed:46

The attorney for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians said in response:47

The Bristol-based developers proposing the Hard Rock casino drew a key distinction between their plan and the less-ambitious Cherokee plan:48

in early 2020, even before the General Assembly authorized casinos, two gambling-based resorts were proposed on the Virginia-Tennessee border

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol, TN 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle and Blountville, TN 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle (2019)

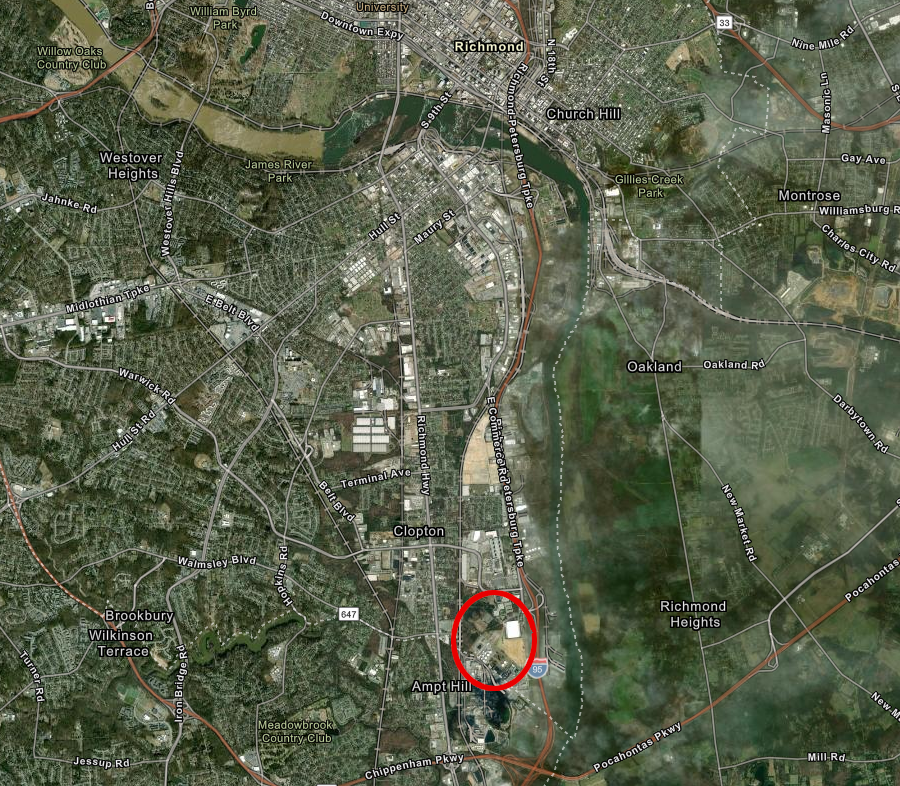

After the Cherokee announced their plans, and while the General Assembly was considering legislation that would authorize casino gambling in Virginia, the Pamunkey announced a proposal for a $350 million resort and casino in Richmond. A 275-room hotel was planned as part of the project, plus a separate workforce training center.

A spokesperson for the Pamunkey noted that a tribal casino could be developed in Richmond under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and be regulated by the National Indian Gaming Commission, if the General Assembly chose not to alter state laws and legalize commercial gaming in the state. Utilizing that authority would exempt the casino from state taxes, if the Bureau of Indian Affairs placed the Pamunkey's property in Richmond within Federal trust. In contrast with Norfolk, the tribe could make a stronger claim that Richmond was within its historical territory. A tribal-state compact would still need to be negotiated, and the compact would probably include a revenue sharing deal in lieu of a state tax.

in January 2020, the Pamunkey announced plans for a casino in Richmond

Source: Facebook, All In For Richmond Casino

The proposed location was less than a mile away from an existing I-95 interchange. Even though the site was south of the James River, 100 miles away from MGM National Harbor in Maryland, a Richmond casino could divert some customers who had been going across the Potomac River.

Virginia residents generated 30% of the revenue at MGM National Harbor and Maryland Live Casino & Hotel. MGM National Harbor could lose as much as $100 million/year in revenue to a casino in Northern Virginia, and half that amount to a casino in Richmond.49

a Washington Business Journal headline after authorization of casino gambling in Virginia made clear that MGM National Harbor could lose business

Source: Washington Business Journal, Virginia moves closer to casino gaming, posing real threat to MGM National Harbor's revenue

Closer to home, Colonial Downs recognized that a full-scale casino in Richmond would reduce business at the Richmond Rosie's off-track betting parlor 10 miles away. That site generated more revenue than any other Rosie's location. The horse racing company and its casino partner requested that it be allowed to expand the Richmond Rosie's into a full scale casino. Colonial Downs suggested that incumbent operators deserved preference, rather than Native American tribes:50

As the General Assembly debated allowing Colonial Downs and the Pamunkey to compete for casino rights in Richmond, some legislators wanted to require casino developers to contract with small and minority-owned businesses. The Pamunkey chief's response was that their casino would be 100% minority owned:51

the Pamunkey proposed a casino in Richmond within one mile of an I-95 interchange

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

At the very end of the 2020 General Assembly, legislators passed a bill allowing Portsmouth, Richmond, Norfolk, Danville, and Bristol to hold a referendum and, if endorsed by local residents, issue permits for casinos. Baccarat, blackjack, twenty-one, poker, craps, dice, slot machines, roulette wheels, Klondike tables, punchboards, faro layouts, numbers tickets, push cards, jar tickets, pull tabs, and on-premises mobile casino gaming were made legal activities in the five casinos.

Tax rates were graduated, as were payments to the host cities. State taxes were 18% on the first $200 million of adjusted gross receipts, with 6% returned to the city. Taxes were 30% on adjusted gross receipts in excess of $400 million, with 8% returned to the city. Of the tax revenue retained by the state, 0.8% was directed to the Problem Gambling Treatment and Support Fund and 0.2% was directed to the Family and Children's Trust Fund. The remainder was available for the legislators to appropriate annually as general fund revenues.

An additional 1% tax was imposed on any casino operated by the Pamunkey, with the money deposited into a new Virginia Indigenous People's Trust Fund. Those dollars were to be distributed equally to the other six Federally-recognized tribes in Virginia. The Nansemond received no special consideration.52

The cities could choose their preferred operator; no statewide competition for permits was created. The Virginia Mercury described the influence of casino operators in shaping the legislation, after noting that the Virginia Senate gambling subcommittee had relied upon a lobbyist to explain the casino selection process and the House of Delegates subcommittee was prepared to do the same until a legislator objected:53

The owner of Colonial Downs, Peninsula Pacific Entertainment, focused on gaming in Danville. It had planned to open a Rosie's Gaming Emporium there after city voters approved a pari-mutuel betting facility in 2019, but in 2020 expressed interest in being chosen as company authorized to open a casino in Danville.

The legislation also allowed Colonial Downs to install 2,000 more historical horse racing machines, raising the total statewide from 3,000 to 5,000 machines. Each time a city authorized a casino, the company could add 600 more machines. As many as 1,650 betting machines could be authorized in Dumfries if Colonial Downs chose to expand in just that location, but it chose to open with just 150 of them.

Dumfries, a town within Prince William County, had approved hosting 150 machines in a 2019 vote. As the only Rosie's Gaming Emporium in Northern Virginia, it offered the closest competition to the MGM National Harbor in Maryland and to the Charles Town Racetrack and Hollywood Casino in West Virginia.54

As soon as the General Assembly approved expansion of historical horse racing, Facebook ads began to object to expanded gaming opportunities in Northern Virginia. Whoever spent $50,000 chose not to identify themselves, but claimed to be locally-oriented with their objections:55

a Facebook campaign against "out-of-state gambling special interests" sought to limit expansion of historical horse racing machines in Dumfries

Source: Facebook, NotInNoVa

Peninsula Pacific Entertainment, owner of Colonial Downs, was based in Los Angeles. However, the label "out-of-state gambling special interests" would apply equally to MGM.

the NotInNoVa campaign began before Dumfries could authorize an expansion to up to 1,650 historical horse racing machines

Source: Facebook, NotInNoVa

Though the initial 150-machine Rosie's Gaming Emporium would be at the Triangle Plaza site, a larger resort could be built at the site of the Potomac Landfill and still be within the town's boundaries. A facility with 1,800 historical horse racing machines could compete effectively with the 3,100 slot machines at MGM National Harbor.

The mayor of Dumfries repeated his desire to create a facility that would attract new business to the town.56

The potential for a casino in Northern Virginia was clear, even though the 2020 General Assembly authorized only five casinos. The groundbreaking ceremony for the new Rosie's Gaming Emporium at Dumfries, a casino-sized gaming facility without casino games, was held while the Potomac Landfill was still operating and trash trucks were delivering construction and demolition debris material to the site.

The City of Hampton hoped to be included in the next round of approvals as well, arguing that a facility on the Peninsula was justified - specifically, near the coliseum.57

Legislation passed by the 2020 General Assembly legalized sports betting, with 12 digital sportsbooks to be licensed and a 15% tax rate on gross gaming revenues. Betting on in-state college teams was banned, however.

Gov. Ralph Northam proposed several significant amendment before the legislature's regularly-scheduled "veto session" on April 22, 2020. He had originally proposed taxing skill-based entertainment machines and directing the funding from a 35% tax on gross profits towards school building repairs. They were omnipresent in truck stops and convenience stores; one distributor had placed 7,500 devices in 2,500 locations.

The General Assembly chose instead to ban the unregulated "gray machines" completely. The governor amended that bill, delaying it a year while imposing a $1,200 per month per machine tax for a year. As amended, the funding would be directed to the pandemic response instead of school repair. The need for emergency pandemic funding was expected to decline, while the need for school repair funding would always be a justification for reauthorizing and taxing the skills-based machines for many more years.

The legislators approved a year of authorized, taxed skills-based machines. It also approved directing tax revenues of casinos to school construction and repair, with the details to be determined by later General Assembly actions before the first casino opened. In the end, legislators did not create any requirement for competitive statewide bidding for the five casino licenses.

Bristol was required by the General Assembly legislation to share gaming tax revenues with twelve nearby counties, members of the Regional Improvement Commission which will receive 6% of the revenues. The state will receive an additional 12%.

12 jurisdictions around Bristol will split 6% of the gaming tax revenue generated by the Hard Rock Bristol Casino and Resort

Source: Vote Yes For Bristol Referendum Committee, What's the Plan?

A 2018 study by an economic consulting firm estimated that the city would gain $28 million annually from existing taxes on meals, lodging, license fees, and admission fees. That optimistic fiscal impact analysis suggested the city could pay down debt and increase services with the 50% increase in annual revenues. Washington County in particular would also benefit from sales and lodging taxes from whatever visitors purchased items within its jurisdictional boundaries, outside of Bristol.

Only the gaming tax revenues, imposed on an estimated $130 million of net gaming revenues, had to be shared with the 12 surrounding counties:58

the Hard Rock Bristol Casino and Resort advertised before the November 2020 referendum that the casino and resort would increase tax revenue by over 50%, before even counting the city's share of the gaming tax revenue

Source: Bristol Casino Resort

The five cities were authorized to hold a voter referendum to approve a casino. Norfolk, Portsmouth, Danville and Bristol planned votes in 2020. Norfolk smoothed the path for voter approval by officially rescinding the deal with the Pamunkey which would have allowed the tribe to add the 13 acres next to Harbor Park to the reservation. If the land had been taken into trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and made tribal territory, the city would not receive any tax revenue from the casino, hotel, restaurants, or entertainment facilities; the tribe would instead have negotiated an annual payment to Norfolk.

the Pamunkey planned to build the Norfolk casino between the Amtrak station and Harbor Park

Source: All In For Norfolk Casino, Norfolk Resort & Casino

Making the operation a simple commercial venture was expected to reduce local opposition to the casino, in advance of the voter referendum in November 2020. The Pamunkey hired lobbyists to create the "All In for Norfolk" campaign, advocating for approval of casino gambling by voters a year before the November 2020 referendum. The campaigning continued despite the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and how it might complicate financing such a major investment.59

advocates for the casino mounted a political campaign to get the referendum approved on November 3, 2020

Source: All In For Norfolk Casino, All In For City Revenue

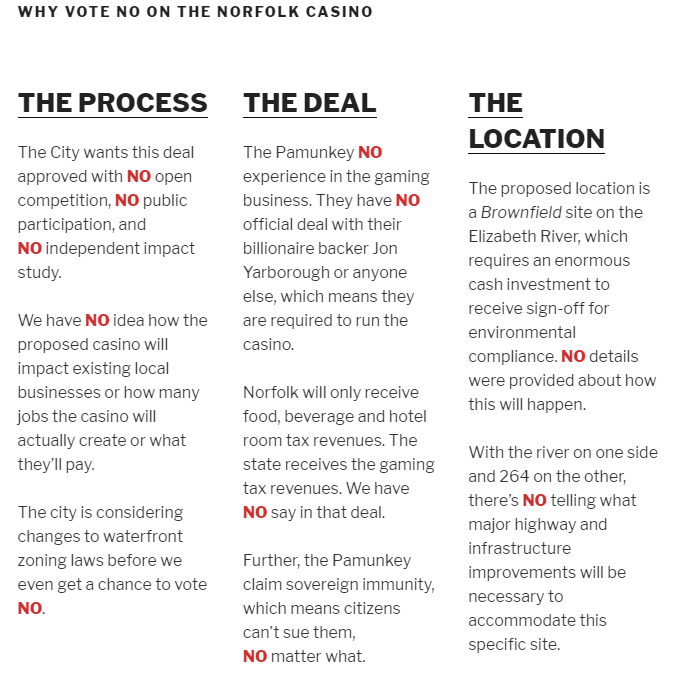

Only in Norfolk was there organized opposition to casino gambling, when four Virginia cities voted on the issue in 2020.

The company operating the Waterside District, Baltimore-based Cordish Company, funded a "Vote No Norfolk Casino" campaign. Cordish Company already owned the Live! Casino & Hotel Maryland at the Arundel Mills Mall south of Baltimore. It hoped to block authorization of a Pamunkey-run casino and create the opportunity for its own deal in Norfolk, by getting voters to reject all casino gambling in the November 2020 referendum.

the Vote No Norfolk Casino effort in 2020 was funded by a rival casino operator, hoping to block approval of the city's deal with the Pamunkey tribe

Source: Vote No Norfolk Casino

Cordish Company also threatened lawsuits. It claimed the lease of Waterside from the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority prohibited the city from subsidizing any major competing restaurant or entertainment projects until 2023. The city noted that it was providing no funding or incentives to the casino, but Cordish Company claimed the exclusive deal with the Pamunkey was an economic benefit prohibited by the Waterside lease.

Both the "All In for Norfolk" and the "Vote No Norfolk Casino" groups initially presented themselves as grassroots efforts, before revealing Cordish was the source of funding. The "Be Informed Norfolk" group claimed to be "a committee of concerned citizens." It highlighted the impact of a casino complex drawing customers away from the restaurants in downtown Norfolk and at the Waterside. The group linked its Facebook page to present the arguments of the "Vote No Norfolk Casino" group, revealing the close connection.

a report in October, 2020 showed how only Norfolk had a funded campaign opposing casino gambling

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, "House Money" Drives Casino Initiatives

One leader of the opposition conceded that residents wanted the economic stimulus expected from the casino and 2,500 permanent jobs. He suggested residents should oppose the 2020 proposal, in the expectation of getting a better deal later:60

the Vote No Norfolk Casino group wanted to replace the Pamunkey tribe as the casino operator, and was not morally opposed to gambling

Source: Vote No Norfolk Casino

the Be Informed Norfolk group was closely aligned with the Vote No Norfolk Casino group

Source: Be Informed Norfolk

All four cities voted in favor of casino gambling on November 3, 2020. The approval percentage of 71% in Bristol was highest in the state. The Norfolk vote in favor, 65%, was lowest of the four cities.

Supporters of the casino initiatives spent $2.75 million to campaign for "yes" votes in the four cities. In Portsmouth and Danville, pro-casino advocates spent less than $400,000 in each city on opinion polling and advertising. The Betting on Bristol group and the Pamunkey Indian Tribe each spent over $1 million in their campaigns. The Informed Norfolk opponents to the Pamunkey proposal spent just $31,000.61

Richmond held no referendum in 2020. At the time the 2020 election ballots were finalized, Richmond had the Pamunkey tribe, Colonial Downs, and Urban One (involved with the MGM National Harbor casino) still negotiating with the city.

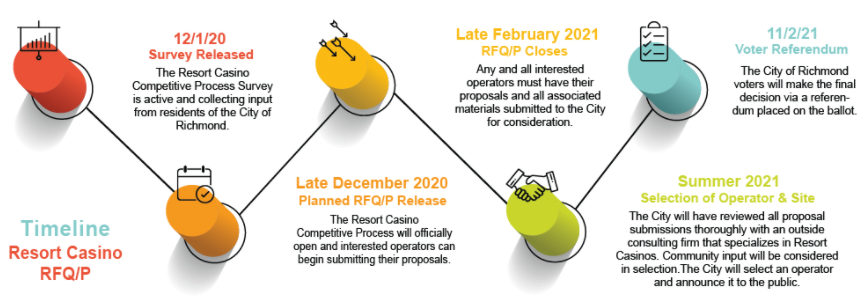

Richmond planned a competitive process to select a preferred casino operator before seeking public approval in a 2021 referendum

Source: City of Richmond, Richmond Resort Casino Development - Learn More about the Competitive Process

Unlike the other four cities, Richmond officials were not prepared to close a deal with the Pamunkey or a different operator. The mayor had just failed in his efforts to get City Council to approve a $1.5 billion project for redevelopment of Navy Hill, and recognized that he needed to build public support before endorsing another new development project that would impact neighborhoods.

Richmond officials held the required voter referendum in 2021, when residents would have a clearer understanding of what development might occur if a casino was authorized. The delay also allowed the election for mayor to be completed in 2020, without casino gambling being on the ballot.

Six competitors submitted proposals for building a casino in Richmond. City officials had to select one, before the voters would authorize a casino in the November 2021 election.

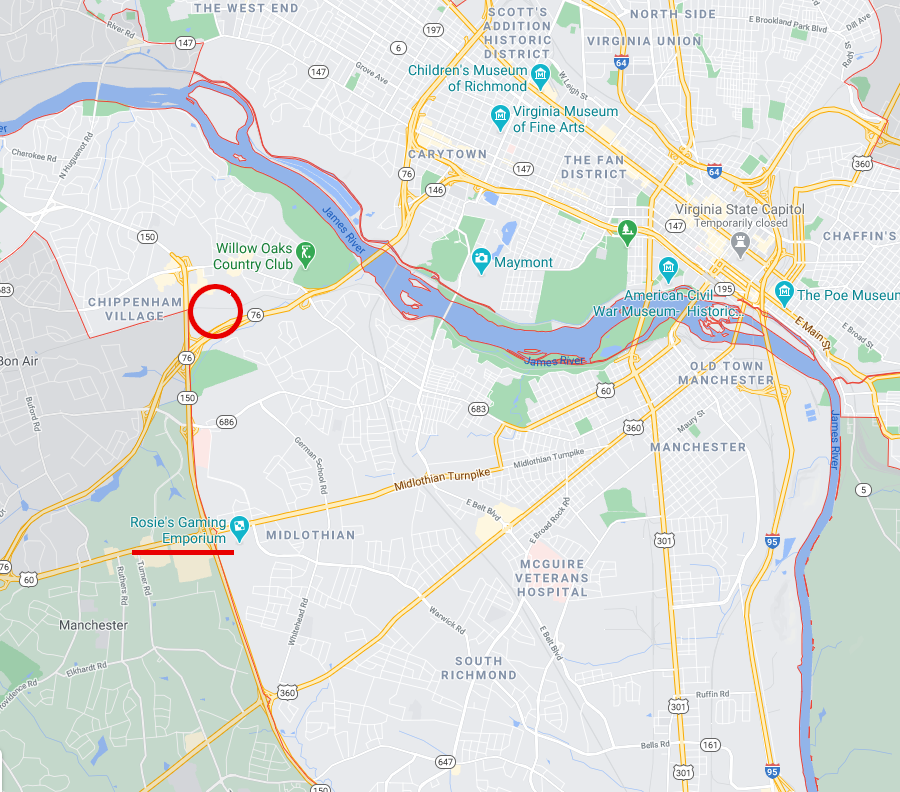

In February 2021, Urban One and Peninsula Pacific Entertainment (owner of Colonial Downs) announced a joint proposal for a $517 million casino and entertainment complex on 100 acres at Exit 69 near the southern edge of the city. Urban One would be the majority partner, and it highlighted the benefits of having a black-owned company getting the license. Urban One already owned four radio stations in Richmond, and had a 7% ownersip in the MGM National Harbor casino. The proposal included offering up to 200 live music events a year for audiences as large as 3,000 people.

Urban One and Peninsula Pacific Entertainment proposed a casino complex at Exit 69 on I-95, on the southern edge of Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Peninsula Pacific Entertainment may have been willing to accept minority ownership because it had just announced plans to expand its Rosie's Gaming Emporium in Northern Virginia. The company's new facility appeared to be a precursor to a full-scale casino in Prince William County. Peninsula Pacific Entertainment had the option of closing its Rosie's Gaming Emporium near the proposed casino, if it was successful in becoming a minority partner in a much-larger project.

The Cordish Companies proposed a casino at the Movieland cinema complex. Wind Creek Hospitality, and authority of the Federally-recognize Poarch Band of Creek Indians in Alabama, proposed a $541 million casino resort at roughly the same location as the Pamunkey had chosen.

Wind Creek Hospitality bid a location where the neighborhood had already objected to a casino proposed by the Pamunkey

Source: City of Richmond, Resort Casino Proposed Locations

The Pamunkey tribe changed its initial proposal, and chose a new location four miles south after objections by the neighborhood to the initial site. Bally proposed building at the intersection of Powhite and Chippenham Parkways, and Golden Nugget announced it was offering to build a $400 million casino resort at the same location proposed by Bally.63

Richmond officials quickly rejected the proposals from Wind Creek Hospitality, the Pamunkey Indian Tribe and Golden Nugget. Left in competition were the proposals from Urban One/Peninsula Pacific Entertainment, The Cordish Companies, and Bally.

Bally's proposal to build at the intersection of Powhite and Chippenham Parkways was accepted by Richmond officials

Source: Bally, Our Commitment to Richmond

Neighbors objected to the location chosen by Bally for a $650 million resort complex, and the company suggested moving to a vacant parcel on Midlothian Turnpike behind the Rosie's Gaming Emporium. City officials refused to consider a last-minute proposal to move locations, after evaluations had screened out three competitors. The city also rejected the company's suggestion to separate the selection of a casino operator and a specific location, which would have changed the rules of the competition to enhance Bally's chances of winning at least part of the business.