possible migration paths to Virginia from Beringea or even Europe

Source: base map from Wikipedia

possible migration paths to Virginia from Beringea or even Europe

Source: base map from Wikipedia

The first people to occupy Virginia, known today as Paleo-Indians, came here from elsewhere. Where they came from, and how they got here, is still a matter of dispute.

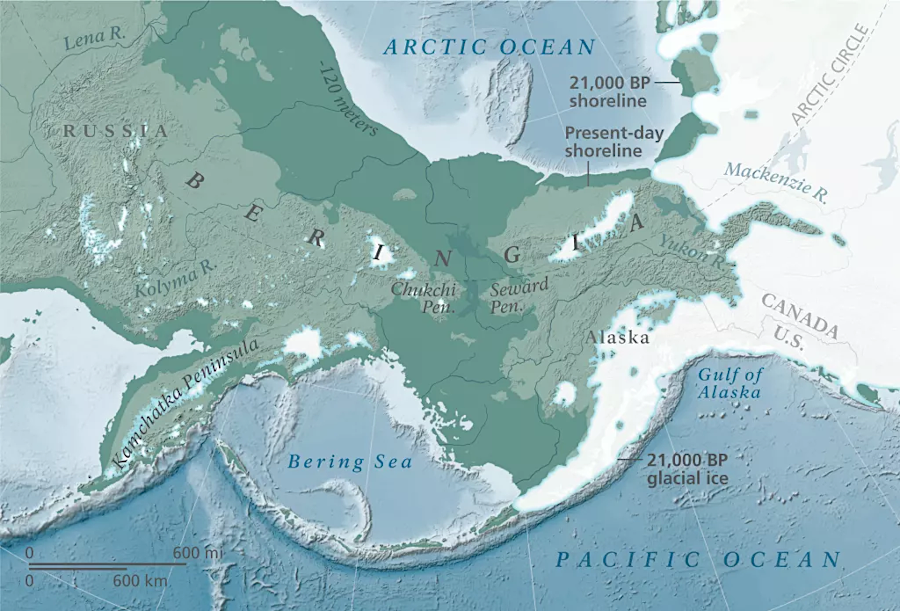

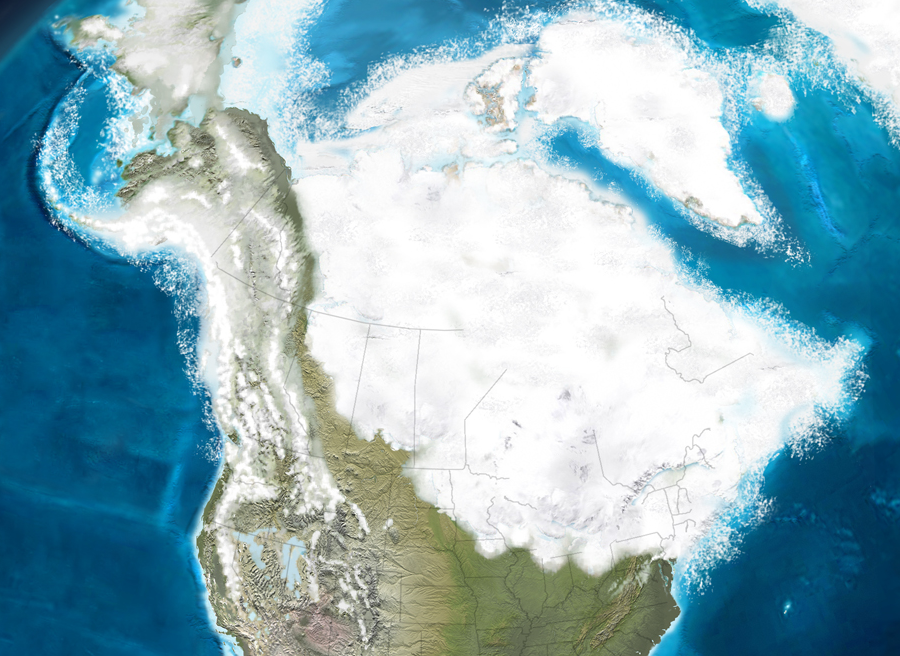

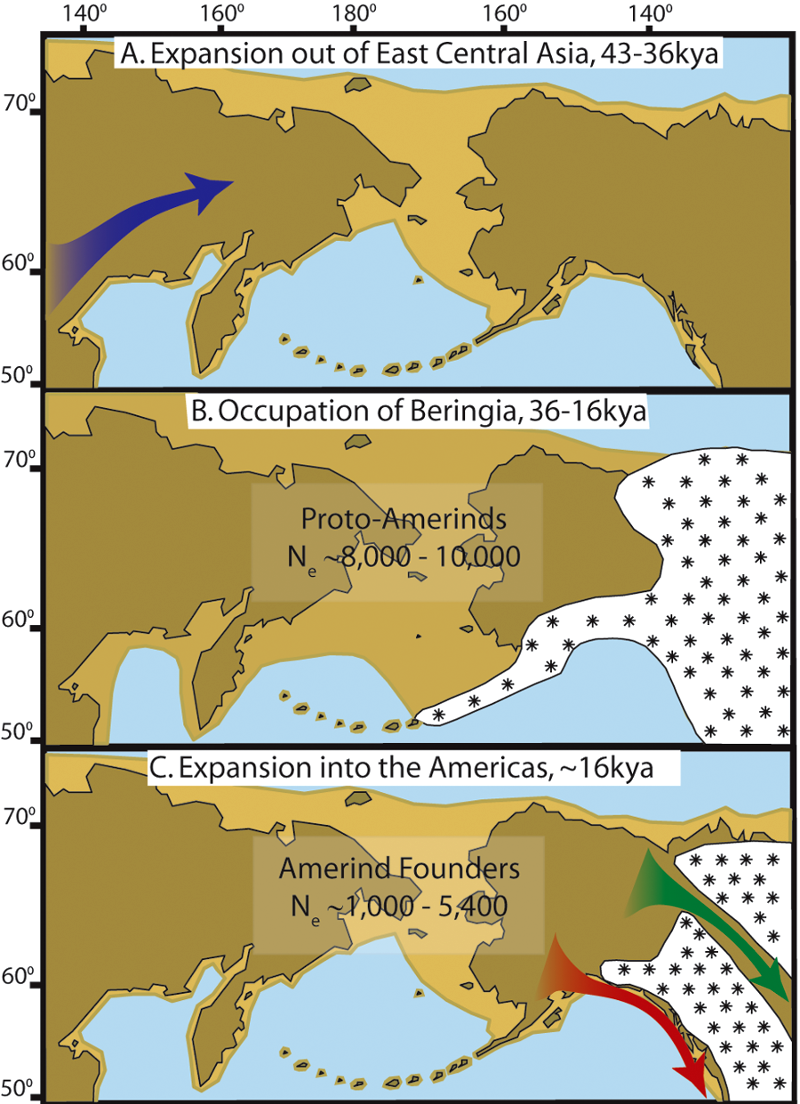

The first humans to occupy North American probably walked first from Siberia, crossing into Beringea as they hunted for game and gathered plant foods. The Beringea connection between Siberia and Alaska emerged around 36,000 years ago, and lasted until 11-13,000 years ago. It was a marshy landscape with small lakes and river channels, not a dry grassland steppe. Ground was solid enough for horses to migrate from North America to Asia, and from bison - and humans - to migrate in the other direction from Siberia into Alaska. The North American camel did not cross to Siberia, however.

Beringea was a homeland to occupants who took advantage of the new habitat that emerged when sea level dropped. People did not occupy the new land as just a temporary pathway in order to migrate into North America; Beringea was occupied as a "home," not just as a "bridge" to somewhere else.

Peple lived in Beringea for 10,000 years before the advance of the ice sheets peaked in the Last Glacial Maximum 26,000-18,000 years ago. Residents used boats in the rivers and on the edge of the ocean. Some moved along the coastline and managed to reach what is now New Mexico by 21,000-23,000 years ago.

the first humans to move into North America lived first in Beringea

Source: Yukon Geological Survey, Paleodrainage map of Beringia (Open File 2019-2, 2019)

Those staying on Beringea may have been isolated by the ice sheets on a 1,000 mile wide marshy grassland, which included northwestern Siberia and Alaska today plus what is now the seafloor beneath the Bering Strait. After ice sheets cut off easy access to Siberia, there was a "Beringian Standstill" when people in Beringea were isolated from both Siberia and North America. They survived on Beringea because a warm current from the Equator to the North Pacific created a habitable refuge, on lands that are mostly submerged beneath the Bering Sea today.

much of the land occupied during the Beringian Standstill is now underwater

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During the last Ice Age, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet covered the mountains along the coastline of what is now called Alaska. That ice sheet stretched westward over what is now the continental shelf, and icebergs calved off the edge of the ice into the Pacific Ocean. Ice eventually blocked all passages out of Beringea, but humans hunted wooly mammoths in the northern regions of Siberia until as late as 26,000 years ago.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet also stretched eastward. It coalesced with the Laurentide Ice Sheet, creating a combined barrier of ice that extended from the frozen Arctic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

For many years it was thought that human migration through the combined ice sheets was not feasible until 14,800 years ago, when a corridor began to open between them again as the ice melted. An ice-free path between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets, stretching north-south completely between modern Alaska and Montana, finally developed 13,800 years ago. Plants grew in the corridor, providing food to the animals and people exploring within it. At some point, even before development of the completely ice-free corriddor, people could cross whatever ice was blocking passage and move to the south.

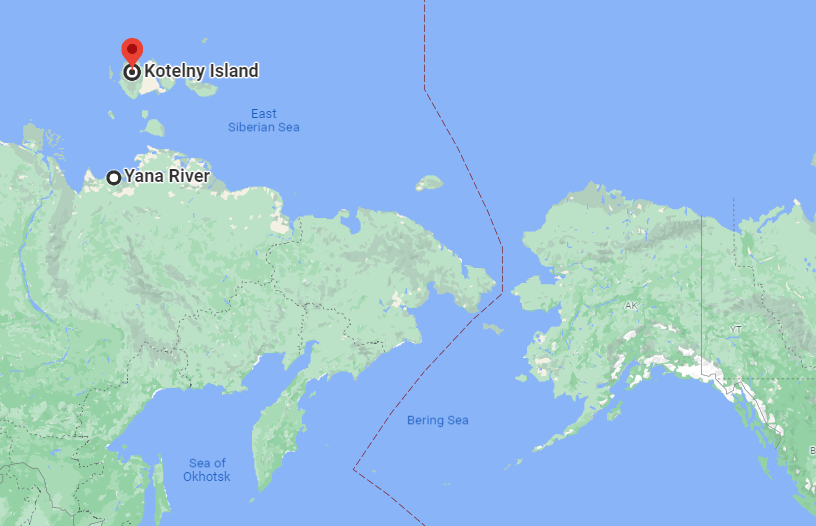

Paleo-Indians hunted on what is now Kotelny Island and the Yana River until at least 26,000-29,000 years ago

Source: GoogleMaps

However, the study of the first human arrival in North America is a dynamic field of study.

The announcement in 2021 of the discovery of 21,000-23,000-year old footprints at Lake Otero, in White Sands National Park in New Mexico, required reconsideration of the traditional scenarios - again. Humans left tracks in the sand there between 21,000 and 23,000 thousand years ago. Tracks were dated through pollen and grass seed trapped in the mud, and the age of the mud itself. Those footprints were made was long before the ice sheets melted far enough to expose a path out of Beringea, and 10,000 years before the development of Clovis points.

Stone tools and teeth from camels and bison at Rimrock Draw in Oregon suggest humans were there 18,250 years ago. Coprolites from Paisley Caves in Oregon have been dated to 14,200 years ago. The Manis spearpoint, made from a mastodon bone and found in what is now the state of Washington, is 13,900 years old. Paleo-Indians south of the ice sheet were carving bone, as well as flaking stone, to make tools 900 years before the development of the Clovis culture.

In 2023, researchers announced their conclusion regarding the age of stone pendants which had been made from giant ground sloth bones in central Brazil. The pendants had been made by people living in the Santa Elina rock shelter 27,000 years ago.

A year later, published reports claimed that human-caused butcher marks had been identified on the bones of a glyptodont. The marks indicate that the 660-pound animal, an ancestor of the modern armadillo, had been cut up for a meal 21,000 years ago.

The conclusion that people were living in Brazil 27,000 years ago is inconsistent with studies indicating that walking across the Bering Land Bridge was possible in just two windows, 24,500-22,000 years ago and 16,400-14,800 years ago. If humans had migrated from Asia to North America and reached Brazil 2,500 years before it was possible to walk across the land bridge, they may have made the intercontinental journey in boats.1

fossilized footprints suggest Paleo-Indians were in what is now New Mexico about 23,000 years ago

Source: National Park Service, Fossilized Footprints

The humans living in Beringia were not seeking to move in any particular direction in order to escape their habitat there. Unlike Columbus in 1492, they were not consciously on a journey to discover a new path to the other side of the world. In contrast to the crew of the USS Enterprise in modern Star Trek movies, they were not tasked by a government to push the boundary of human knowledge, to "go where no man has gone before."

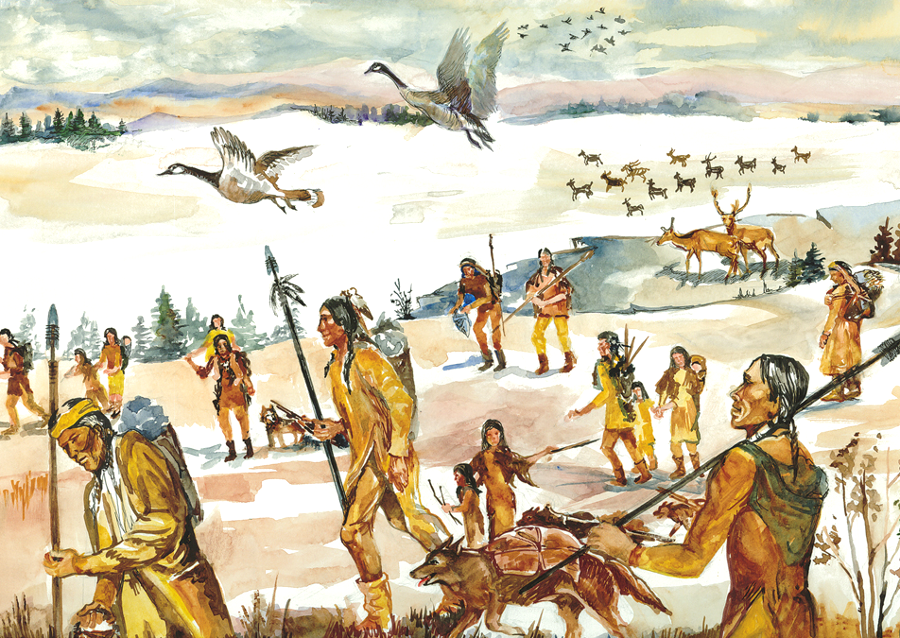

The first people in North America were hunters and gatherers, constantly exploring in search of another meal and a safe place to sleep. They communicated with each other in a precursor to the Sino-Tibetan languages that developed about 6,000 years ago.

People living in Beringia probably adopted a seasonal pattern of moving around, returning each year to sites known to be rich in ripening plants or migrating animals such as caribou. Hunters knew when seals frequented specific locations for breeding, and when those places were empty. It is likely that both men and women were hunters, based on the discovery that women are hunters in 80% of foraging societies that have been studied. The concept that patriarchy is justified by the inequality of how food was acquired, starting thousands of years ago, is not sustained by the evidence.

At each temporary campsite, local food resources were soon exhausted. On a regular basis, the people in Beringia packed up their stone and bone tools, furs, skin containers with everything else they owned. They were constantly on the move to find new plants with edible seeds and fruits, and more animals such as mammoths that would reduce hunger for the moment. Older people constantly taught younger ones simple tasks such as how to manage fire and complex tasks such as how to interact with other groups when their paths crossed. Training occurred through example, and certainly without textbooks or YouTube videos.

There were no permanently-occupied houses, because no location offered a year-round source of food sufficient to feed an entire hunting band. Paleo-Indians were migrants, constantly on the move. Old campsites would be re-visited if there were good food sources nearby. Returning to an old site would require less time to gather stones to make a hearth, or small tree trunks to be used as tent poles. Otherwise, everything they owned was carried from place to place, hung from their waists and on their backs/shoulders. One of the first steps in making camp would have been stripping off the sacks made from skins of animals and woven bags made from plant fibers.

Each generation had to adapt to a changing environment, modifying traditional patterns in the seasonal round for travel to certain places. Each generation had an opportunity to modify how to strip bark and fibers to make needed materials from different plants, and how to kill and process animals.

while isolated in Siberia/Beringia, humans hunted woolly mammoths and other animals that grazed on the tundra, grasses, and small trees

Source: PLoS ONE, What Killed the Woolly Mammoth? (Caitlin Sedwick, 2008)

Perhaps 6,000 to 10,000 migrants lived in Beringia for at least several thousand years. They adapted to the cold climate, and survived on the ice-free steppe and tundra that was suitable for hunting and gathering.

Humans probably tried to walk across the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and Laurentide Ice Sheet, even at the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum. Adventurous or starving hunters might have packed food and traveled a few days deep into the ice sheets that blocked efforts to travel to the east and south. Paleo-Indian bands with a surplus of food, perhaps after killing a musk ox, may have established food caches on the ice to extend the distance that could be traveled by explorers.

Leaders of bands may have looked for a path through the ice to occupy new territory, ideally with new food sources and a chance to avoid conflict with hostile family groups. Spiritual visionaries may have spurred expeditions onto the ice.

Savvy observers responsible for deciding where to forage must have noticed that birds appeared each summer from the south, crossing over the ice sheet to spend the summer in Beringea. If there was a place beyond the ice sheet with food and shelter for birds, then humans could live there too... if only they could get past the ice.

Some humans always want to go farther, to explore, to discover, to climb higher "just because it's there." Some intrepid explorers seeking to get across the ice must have returned back to camp hungry, with stories of blinding white land but no better places to live. Other explorers, and perhaps social outcasts who were forced to seek new places to live or those trying to get away from dangerous rivals, must have died on journeys across snow and ice that provided none of the necessary resources.

The main constraints to moving out of Beringia were food and fuel. Where ice covered the soil completely, there were no dwarf birch, willows or other shrubs to provide materials for building any form of shelter. Plants were required as "starter fuel" for the initial fires that would grow hot enough to ignite the marrow in large mammal bones, the greatest source of energy available for keeping warm.

the Cordilleran Ice Sheet blocked humans from moving past the eastern edge of Beringea

Source: National Park Service, About Beringia

Bands of earliest Americans who left the shrub tundra during the Last Glacial Maximum might find shelter from the winds by sleeping in large cracks within the moving ice sheets, but could survive only briefly without plants and animals for resupplying food. Without vegetation for fuel, even melting ice for drinking water would have been a challenge.

For a long time there was nothing inland from the ocean's shoreline but ice, ice and more ice. Short explorations on the ice sheet were feasible, but no one returned from a trip into the ice-covered interior of Alaska that lasted longer than the food supply carried by the travelers.

One of the major innovations of early humans was the invention of the eyed needle, made from the bones of small carnivores such as red foxes and rabbits. Needles allowed closer stitching of furs and skins than awls that were made from larger bones, so clothes provided greater warmth in northern latitudes.

the tundra steppe of Beringia provided food for thousands of years, before ancestors of Paleo-Indians in North America migrated past the ice sheets

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Cold Land Processes Field Experiment Plan

However, in another example of how the knowledge of early human occupation is changing, the traditional assumption that no one succeeded in crossing the ice sheets during the last Glacial Maximum may have to be reconsidered. In 2017, scientists published details of a site in northwestern Yukon where humans had lived 24,000 years ago. Somehow people reached the Bluefish Caves in Yukon Territory. They may have migrated there before the ice sheets spread to their greatest extent, but they may have reached the caves before the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated.2

ice sheets blocked early North Americans from moving south from Beringia primarily because there was no food for hunter/gatherers

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA Data Peers into Greenland's Ice Sheet

As the climate grew warmer at the end of the Ice Age, land once covered by ice was exposed. The ice-free path to the south may have opened up first along the edge of the Pacific Ocean, as the Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreated eastward from the coastline and north from the Olympic Mountains and Puget Sound. At some time, long-distance explorers managed to cross the remnants of the combined Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets and get direct access to the interior of North America. The hunting opportunities, in an environment where animals were unaccustomed to the newly-arrived predator, must have been extraordinarily rich.

Of the original immigrants from Siberia that were stranded in Beringea, a "founder group" - perhaps just 250 individuals or perhaps 5,000 people - could have reached California by traveling along the western edge of the melting Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Whatever the number of first arrivals, the founder population had a limited gene pool. Analysis of DNA today reveals evidence of a genetic bottleneck. Perhaps a small number managed to get beyond the ice sheets over 23,000 years ago, but further expansion of the ice blocked more migration until 17,000 years ago.

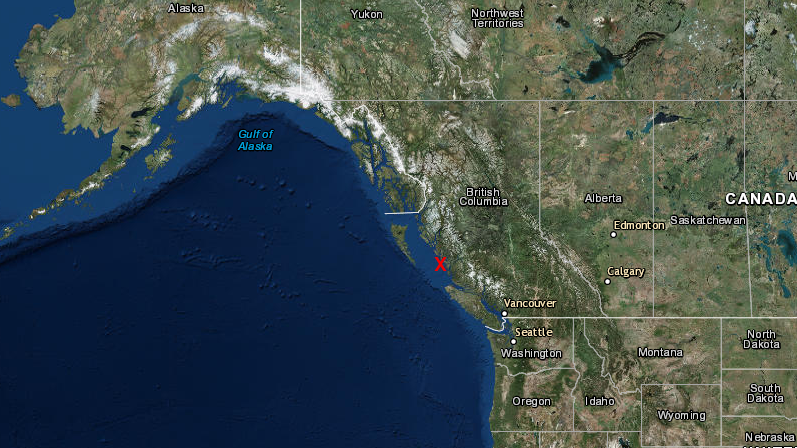

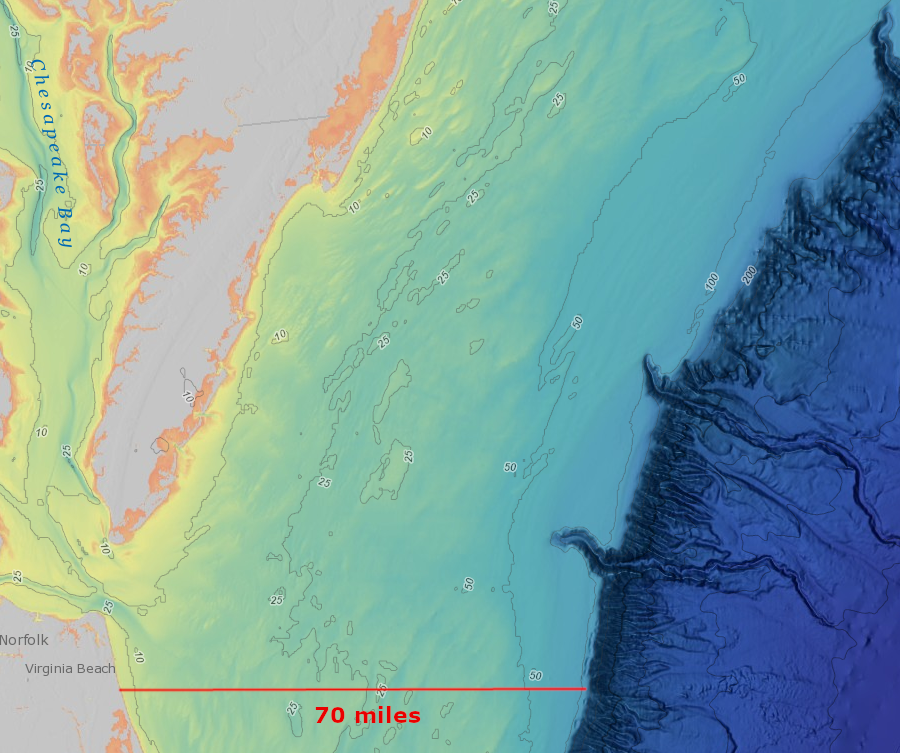

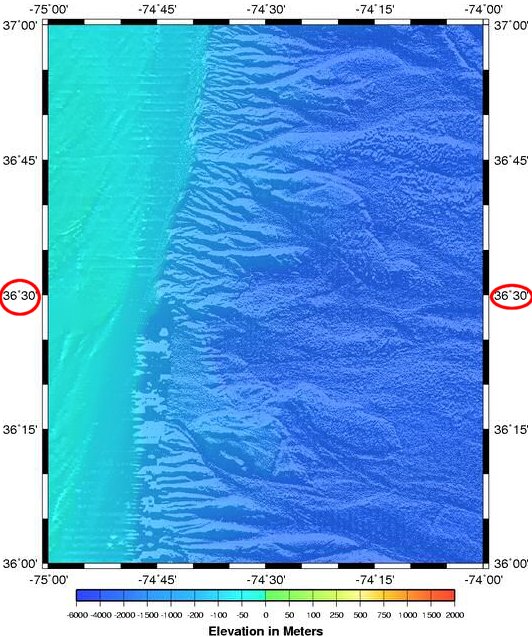

About 17,000 years ago, sea levels were nearly 400 feet lower than today. The shoreline along which the Paleo-Indians could have walked was 50-75 miles further west than the modern land-water edge.

Many of the original campsites of those immigrants are deep underneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean, but parts of the ancient Pacific Ocean shoreline have "bounced back" after the ice sheet retreated and the weight of ice was removed. The oldest Atlantic Ocean shoreline campsites in Virginia are 400 feet beneath the ocean surface, drowned by sea level rise, but some of the oldest campsites in Alaska, British Columbia, and the Pacific Northwest may be on dry land due to land uplift.

Discovery and research into sites along the Pacific Ocean could provide evidence of the migration. Underwater research may also illuminate the past. England and Scandinavia were connected by a land bridge until about 8,000 years ago, and archeologists are exploring for evidence of human occupation in "Doggerland" which is now underneath the North Sea.

Human migrations continued between Siberia and Alaska even after the ice melted, sea levels rose, and the continents were no longer connected by a land bridge. Glass beads from Venice have been discovered at an archeological site which was dated to 1397-1488 Common Era (CE) near Kotzebue, Alaska. The beads were prestige trade goods which had been transported from Venice via the Silk Road to China. Evidently kayakers in Siberia carried the beads over 50 miles across the Bering Strait.

an archeological site neat Kotzebue, Alaska shows continued migration from Asia to North America just before Columbus reached the Caribbean in 1492

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Assuming the archeological date is correct, those Asian travelers reached North America long before Columbus "sailed the ocean blue" in 1492 to the Caribbean. Travel to North America by boat could have been a common experience ever since the Ice Age, not a new travel mechanism developed by Vikings or later Europeans.

People from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) sailed to South America between 1250-1430 CE (Common Era). That island had been settled originally from Polynesia. Genes of South Americans in the bones of ancient islanders show that some sailors kept going east, and then returned back to Rapa Nui from South America.3

sailors from Rapa Nui traveled over 2,000 miles eastward to reach South America between 1250-1430 CE (Common Era)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Deglaciation was a slow process, but hunters and gatherers found an ecologically viable pathway when the Cordilleran Ice Sheet melted back and exposed coastline and islands 17,000 years ago. People somehow managed to walk/boat south and occupy Monte Verde in Chile 14,500 years ago.

Populations in Siberia with distinct DNA may have crossed the Bering Straight into Beringea and then North America in three "waves" approximately 20,000, 5,000 and 1,000 years ago. Native Americans also traveled back to Siberia during that time. They walked until rising sea levels separated the continents, and crossed the Bering Straight by boat starting 6,000 years ago.

Evidence shows that humans reached Triquet Island, now in modern British Columbia, 14,000 years ago. If the first humans to move south from Beringia used the shoreline route rather than an ice-free path inland between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets, they ate seafood on their journey. They may have used boats or walked along the "kelp highway," and enjoyed a "surf" rather than a "turf" diet.

Melting glaciers in the summer would have created strong ocean currents between 20,000-14,000 years ago. Migrating people might have chosen to move in the winter, perhaps even using dogs to carry gear across the pack ice. Marine mammals would have been a food source for such trips, which were feasible as long as 25,000-30,000 years ago.

A second surge of migration may have occurred around 13,000 years ago, once the inland ice-free corridor became passable. The oldest human bone found so far in North America is dated as 13,100 years old. It came from one of the Channel Islands off the coast of California,

when migrants reached Triquet Island 14,000 years ago, sea levels were lower and the shoreline was 50-75 miles further west

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Some genetic evidence suggests that around 13,000 years ago, the immigrants who had arrived in Beringea 10,000 years earlier split into two groups that populated North America in two separate migrations south. Other evidence suggests a steady flow of people from Beringea into North America without "waves," with one common set of genes. Today, up to 2% of the genes of indigenous peoples in the Brazilian Amazon are the same as in indigenous peoples of Australia and New Guinea, but scientists disagree on how those genes arrived in the New World.

Migrating from Beringea westward into what is now Russia may have taken longer than travel south to what is now California; long-distance boat trips across the Bering Straight required different technology and skills than short trips along the coastline. Beringea remained isolated from Siberia until about 5,000 years ago.

After the Bering Straight developed, only boats allowed continued migration in both directions. About 800 years ago, another wave of Siberians moved across the Bering Straight and became the ancestors of the modern-day Inuit and Yup'ik peoples.4

humans - perhaps the first to reach North America - traveled along the edge of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet

Source: National Park Service, Kenai Fjords National Park, Plant Succession

At the Manis site on the Olympic Peninsula, in 1977 archeologists found a spear tip embedded into a mastodon bone. The spear tip was also made of bone, and they were dated to 13,800 years ago. The Manis site, occupied nearly 1,000 years before an ice-free corridor emerged between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets, added evidence that humans boated around the edge of the ice sheet.

People quickly migrated all the way to the tip of South America. A footprint of a 155-pound human in Chile has been dated to 15,600 years Before Present (BP), equivalent to 13,600 Before Common Era (BCE).

By some route(s) not yet identified, people moved inland from the Pacific coast. At Buttermilk Creek in Texas, archeologists have discovered projectile points in soils that are 13,500-15,500 years old.

Tools, animal bones, and charcoal at Cooper's Ferry in Idaho date back to 16,560-15,280 calibrated years before the present (cal BP). That site suggests the Pacific coast migration route included an "off ramp" up the Columbia River to inland sites, perhaps used by migrants who came south after the ice sheets began to retreat 18,000 years ago.5

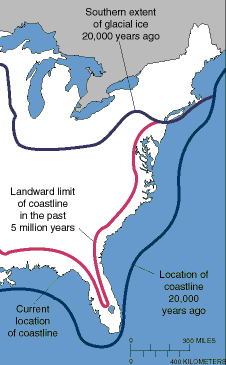

The humans who reached what is now New Mexico 23,000 years ago apparently crossed the continent and reached Virginia. Somehow they crossed wide and fast-flowing Ice Age rivers, including the Mississippi. The first immigrants were skilled kayakers, successfully moving along the Pacific Coast. They may have boated across the wide and braided channels of the Mississippi River along what was the Gulf of Mexico coastline 20,000 years ago. Since sea levels were 400 feet lower, that coastline would have been further south than modern New Orleans.

Paleo-Indians crossed the Mississippi River when sea levels were lower and melting ice may have generated a wider river

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The coastline of the eastern U.S. changes... slowly

It is also possible that they moved north to near the headwaters. Being close to the ice sheet would have required using the skills developed in Beringea for hunting on the edges of periglacial lakes, and protecting against the cold winds blowing off the ice sheet.

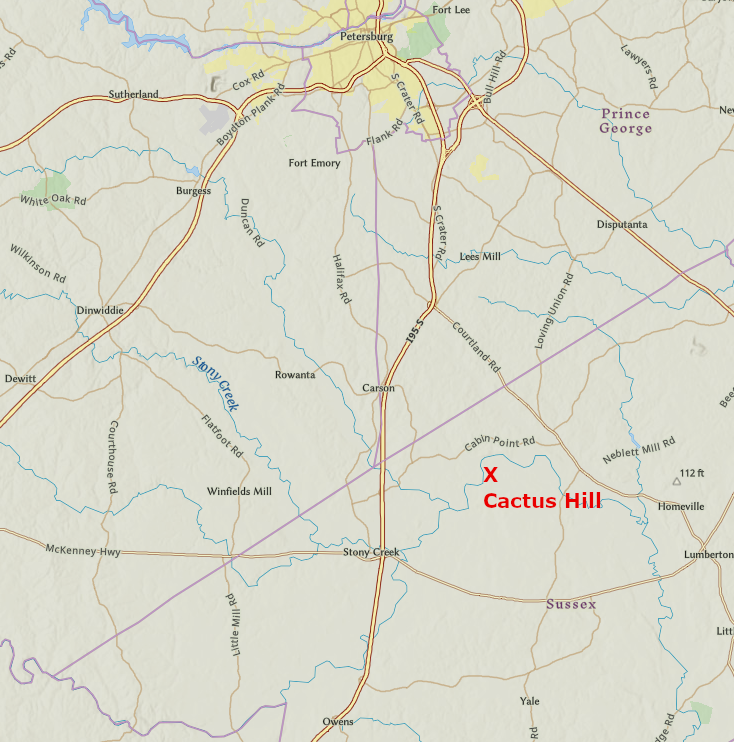

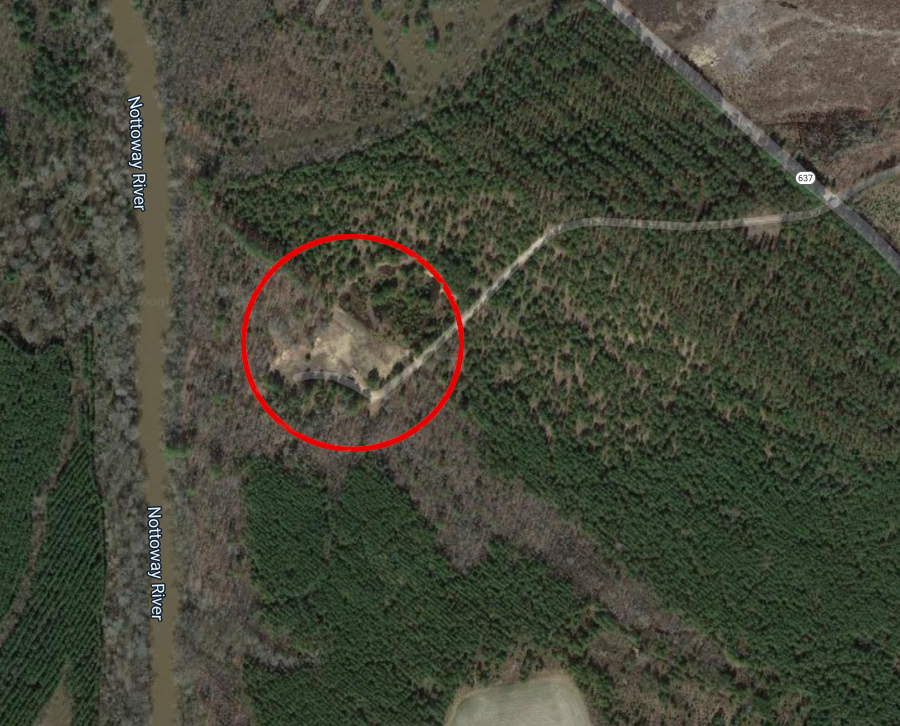

Evidence at Cactus Hill, along the Nottoway River in Virginia, indicates that site was occupied by Paleo-Indians as long as 15-20,000 years ago.

The north-facing slope along the proto-Nottoway River at Cactus Hill and a similar site at nearby Blueberry Hill would have been swept by steady winds blowing off the ice sheet. In the winter, the cold winds would driven Native Americans to camp in sheltered stream valleys. In the summer, the winds would have driven away biting/stinging bugs. Ridgetops, including what is now Parson's Island in Delaware, would have been desirable camping sites.

Human-created artifacts, embedded with charcoal dating back to 22,000 years ago, have been recovered from sites buried by moving sand on Parsons Island. Interpretation of the evidence remains a hot topic of discussion, but the evidence could indicate Pale0-Indians arrived thousands of years before the Clovis culture developed.

Charcoal flecks at Cactus Hill associated with Clovis artifacts have been dated as 10,920 years 14C yr BP (about 12,500 cal yr BP). Similar flakes below the Clovis level, thought to be associated with a human-managed fire, have been dated at 15,070 14C yr BP (about 18,200 cal yr BP).

An Optically-Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) date at Cactus Hill is 17-20,000 years BP (Before Present). The OSL technique measures the last time quartz sediment was exposed to light. After humans no longer occupied the site, sand covered the surface and blocked sunlight. Without sunlight, electrons stimulated by natural ionizing radiation stayed trapped in the crystal lattices of buried quartz grains. Archeologists and geologists trying to date when people were living at Cactus Hill carefully excavated and stimulated those grains to release photons of light, and the luminescence indicated the surface was buried around 15,000-17,000 BCE.

The sand was blown by cold winds coming off the ice sheet, especially at night when humidity was low. Sand dunes in the Carolina Sandhill region were formed between 75,000-6,000 years BP (Before Present time). During that time, sand dune formation was interrupted by two warmer and wetter periods totaling 15,000 years. In those two periods, as in the most recent warmer and wetter 6,000 years, plant growth stabilized the soils and interrupted the creation and movement of the dunes.

However, one sample at the site was dated with an inconsistently young age. Skeptics of the pre-Clovis evidence at Cactus Hill note two key shortcomings in the data:6

Cactus Hill is near the Nottoway River in Sussex County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

People lived in what is now called the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in western Pennsylvania between 14,000-16,000 years ago. Humans had lived in North America for thousands of years before they developed the Clovis point around 13,500 years ago.

The eastern edge of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and the western edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet finally separated roughly 13,000 years ago (BP, for "Before Present"). A gap between the two ice sheets opened up an inland route south to expose dry land and meltwater lakes. The human migrants could not carry a supply of food and fuel from what is now Alaska all the way south. They had to wait until the ice-free corridor was filled with plants and animals, creating a suitable habitat for hunters and gatherers.

Very possibly, no one left modern-day Alaska with the intention of going on a long journey south to colonize the middle of North America. Most likely, humans moved into the ice-free corridor as the habitat became survivable. Different bands wandered through the new territory, then emerged into what is now Montana and the Dakotas.

a land corridor between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheet finally opened up and allowed migration to the center of North America

Source: Dr. Ron Blakey, Northern Arizona University, Paleogeographic map of the North American continent during the Pleistocene Epoch

The gap between the western edge of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and the eastern edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet developed after the initial migration into what today is the continental United States.7

Evidence is strongest for the commonly accepted theory that the Western Hemisphere was populated by migrants who crossed into Beringea, and were blocked from moving further east by the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. They migrated south into North America perhaps 15-20,000 years ago, when sea levels were lower. However, there is an alternative possibility to the Siberians-migrated-via-Beringia hypothesis. Even if the vast majority of the first North Americans came from Beringea, it is possible that a few may have managed to find other routes.

In addition to the migrants from Beringea, some of the first people in North America could have arrived from Europe by boat, moving along the Atlantic Ocean coastline and hunting marine mammals at the edge of the ice. The Clovis points found in some of the earliest archeological sites in North America, and perhaps the point dredged up together with a mammoth skull from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean off the Eastern Shore in 1974, might be consistent with the theory that North America was settled by people from the Solutria region in France who paddled here from Europe.

the first Virginians arrived when sea levels were about 400' lower, and the edge of the Atlantic Ocean was perhaps 70 miles east from the modern shoreline

Source: National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

There is even the possibility that some humans reached California 130,000 years ago, based on one set of mastodon bones. They have fractures that may have been caused by tools, though few professional archeologists accept that interpretation. Weighing the evidence requires critical thinking as well as an open mind, though the standard phrase that "extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof" still applies. The controversy over abandoning the Clovis First model demonstrates the challenge in assessing when was North America first settled, and the from which source controversy has not ended.8

The isolation of Paleo-Indians who lived in Beringea would have been mitigated somewhat by man's best friend. Genetic evidence suggests dogs arrived in North America about 16-17,000 years ago. Other evidence suggests dogs were domesticated in East Asia about 15,000 years ago and migrated together with humans across the Bering Land Bridge. The oldest known dog artifact in North America is a tooth 13,100 years old, found in a cave in British Columbia.

Dogs were already domesticated before the end of the Beringea Standstill, when ice sheets blocked movement into North America. Dogs, domesticated Asian wolves, accompanied the people who crossed the Bering Land Bridge. The grey wolves of North American stayed wild; they were not domesticated after humans entered North America.

It is possible that the people trapped at the start of the "Beringean standstill" had no domesticated dogs with them. A later group moving from Asia onto Beringea may have brought the first domesticated dogs, arriving before the ice sheet melted enough for a coastal route south to open.

Dogs could have been hunting companions, pets, and beasts of burden in the exploration from Beringea to California. Man's best friend may have been mammoth's worst enemy. Harassment and distraction by dogs may have been key to how a small group of people with spears perhaps 10' long were able to kill such a large creature.

Dogs may have ridden in boats with some of the early human migrants who paddled along the Pacific Coast shoreline. Dogs could have pulled sleds for later immigrants who walked through the ice-free corridor that developed between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets, once that corridor had sufficient vegetation to support travelers.

Dogs reached Virginia long before Europeans, but the very first Native Americans to camp on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean may have arrived before domesticated dogs were common companions. The initial dogs to reach Virginia probably served as pets and as hunting partners, and perhaps as food. Dogs were the only domesticated animals in Virginia before Europeans arrived.9

Paleo-Indians brought dogs to Virginia, and they may have hunted in packs like wolves

Source: National Park Service, Mollies Pack Wolves Baiting a Bison

The first humans to settle in Virginia, the Paleo-Indians who immigrated here roughly 15,000 years ago, lived by hunting animals and gathering plants. They traveled widely in family-based groups. They moved to new places when local resources were exhausted, rather than settle in one place for more than a few days.

The first Virginians could have crossed the North American continent as fast-moving hunters, migrating steadily into unexplored country to seek out prey. In the "technology oriented" model postulated by scholars of the Paleo-Indian Period, the design of their stone points and the availability of large mammals could have resulted in consistently successful hunts. Few delays may have been required for choosing where to go, or resupplying in case the next territory offered poor hunting.

Alternatively, the "staging area" model postulates a sequential series of migrations, intermixed with occupation of selected areas for longer periods of time. The Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers could have provided such attractive places to live that Paleo-Indians chose to continue to hunt and gather in those valleys for one or more generations, rather than keep moving across the mountain ridges to occupy more virgin territory and ultimately reach Virginia.

Pauses would have allowed for cultural change by different groups in different places, Cultural change would be documented by variations in the styles of Clovis points in different staging areas. Archeologists find some differences, particularly in the techniques of shaping the base of the point where it was attached ("hafted") to the spear. How one chooses to interpret those differences, and whether the data supports the "technology oriented" model or "staging area" model, shapes conclusions on how fast the Paleo-Indians moved from Beringea to Virginia.10

Assuming Paleo-Indians slept in shelters made from fiber mats or skins, they had to haul their roofing materials by hand whenever they moved or manufacture new shelters wherever they stopped. Natural shelters would have been very limited. Traveling bands may have set up temporary camps with a natural wooden roof, after finding places where windstorms had knocked down enough trees to create dry spots for a few individuals. Some Virginia caves and rock overhangs were used, but groups that occupied the land east of the Blue Ridge found few such sites.11

Source: The Archeological Conservancy, An "Idiot's Guide" to the American Upper Paleolithic

The lives of each band, and the prestige and marriage potential of each hunter, depended the effectiveness and efficiency of each hunting and gathering expedition. During the initial migration into North America, there may have been a constant process of experimentation. Food gathering and cooking techniques, spiritual beliefs, and a wide range of behaviors must have changed as the new continent was explored for the first time, but speculation is required to understand their lifestyles. Only stone artifacts have survived to reveal the ancient cultural adaptations to different environments.

Hunters crafted points from bone, shell, antler, and wood as well as different types of stone. The Atlantic Ocean shoreline was 40 miles further east of its current location when Paleo-Indians first arrived. Though the rich supplies of seafood must have provided a strong reason for staying near the coast once people first arrived there, the eastern edge of the Coastal Plain was far from the source materials of the Blue Ridge or Piedmont. There were probably cobbles in the paleo-channels of the Susquehanna and James rivers, but few rock outcrops to supply stone for spear tips or for the knives used to cut skins and fibers.

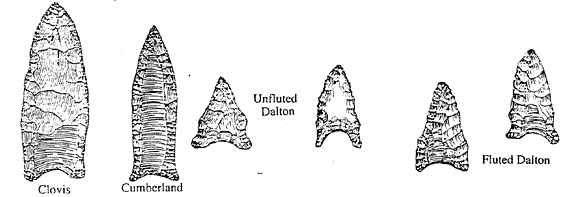

The Paleo-Indians must have tried making points with different shapes and types of edges as they encountered new plants and animals to convert into food and clothing. The evolution of points demonstrates that people tried to improve upon existing tools to be more successful when hunting different types of animals, and changing forms and materials used for knives/scrapers/awls suggest shifts in population.

Clovis Points, with distinctive "flute" of stone chipped out of the center at the base, were the dominant technology 13,250 and 12,800 years BP (Before Present)

Source: National Park Service, Southeastern Prehistory - Paleoindian Period

One of the oldest point designs, the "Clovis" point, is found in Paleo-Indian sites across North America. The namesake discovery site is the town of Clovis in New Mexico. Clovis points are found in some of the oldest - but not the very oldest - archeological sites in Virginia.

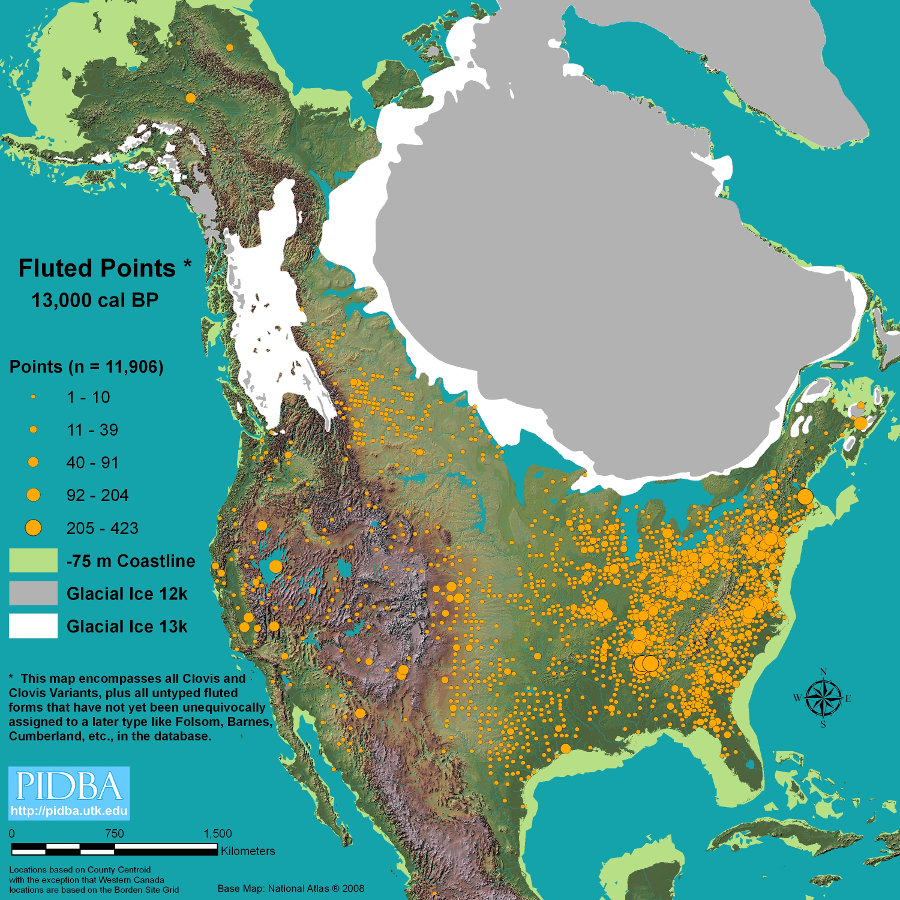

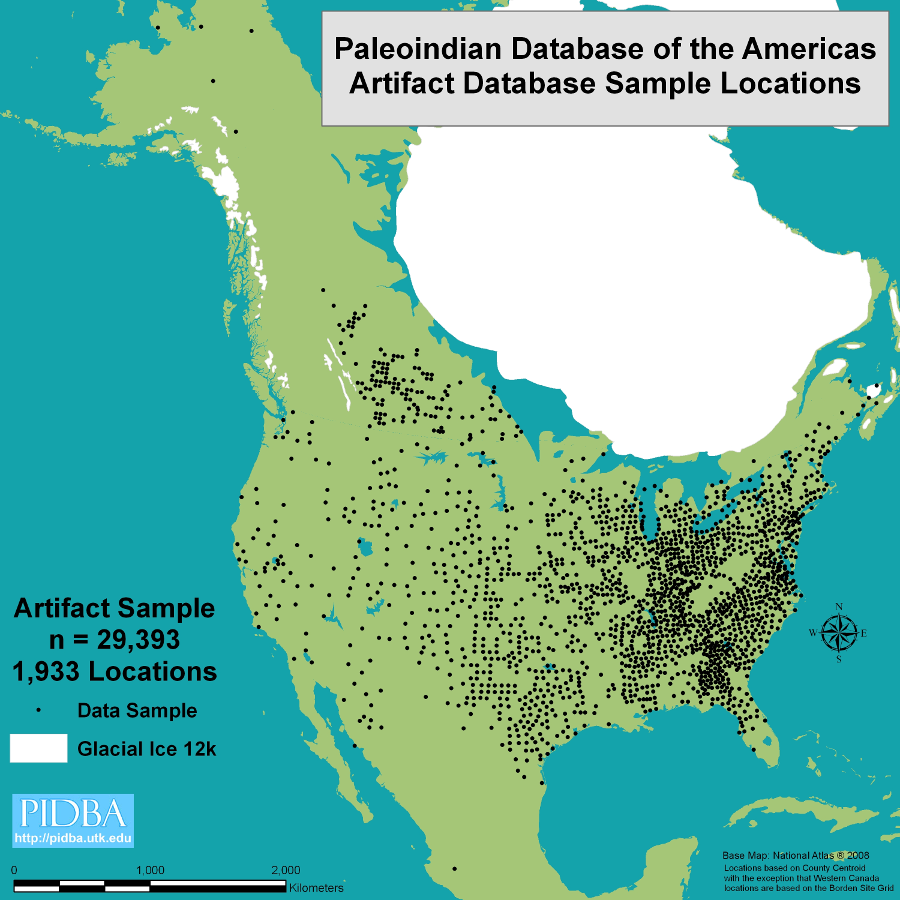

Most archeologists believe Paleo-Indians migrated first into the western side of North America and the oldest sites with Clovis points are west of the Mississippi River, but the greatest concentration of Clovis points is on the eastern side of North America. There are no precursors to the Clovis point in Siberia or Alaska. That design appears to have been developed in North America, and was in use for 20 generations (500 years) after its development 13,400 cal yr BP.

the oldest sites with Clovis points are west of the Mississippi River, but there are more sites east of the river

Source: Paleoindian Database of the Americas, All Fluted Points

The design could have started east of the Mississippi River, and through cultural diffusion spread westward to the Pacific Ocean. Clovis points have their technological advantages for hunting large game, but rapid spread suggests it may have been associated with a spiritual philosophy that made adoption of the design especially popular.

It is also possible that wide-ranging groups carried the design as they migrated into new territory. People occupying spaces that were previously "empty," but became more attractive as local environments changed at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, could have literally carried Clovis points across the continent. Rapid migration, without a unifying spiritual perspective that included a new design, could explain some of the diffusion.12

The Clovis point has a distinctive groove or "flute" in the center. The first people to make a Clovis point might have done so by accident, followed by trial-and-error, followed by intentional shaping of the stone to create the fluted point.

Removing stone from the middle of the point could be viewed as weakening it. A weaker point would crack easier, forcing the band to spend time finding a new quarry site to manufacture more replacements. Time spent replacing points would cut into the time available for collecting food. Making a less-reliable point would be counter-productive.

Clovis points were also harder to manufacture. Each point required about 30 minutes to make by "knapping" stone using pressure to peel off flakes. Near the end of the process, 10-20% of points were ruined when removing slices of stone to create the groove. Nonetheless, Paleo-Indians continued making Clovis points for 300-400 years. The shape had to offer some advantages, to be worth the extra effort required in the manufacturing process.

One obvious advantage of the groove is that it reduced the weight of the point, allowing a hunter to throw a spear farther/faster. The shape also may have reduced aerodynamic drag.

Testing has revealed a third advantage. The groove causes the point to crush near the base upon a hard impact, but protects the point from cracking in the middle. A Clovis point that hit hard bone in an animal could be reworked easily into a shorter, but still fully serviceable tip for a spear. An archeologist who identified the "shock absorber" advantage of the groove noted:13

people from Beringea first migrated into the interior of North America along the Pacific shoreline (red arrow), and later through a gap between ice sheets (green arrow)

Source: PLoS ONE, A Three-Stage Colonization Model for the Peopling of the Americas (by Andrew Kitchen, Michael M. Miyamoto, Connie J. Mulligan, 2008)

Spears tipped with Clovis points were useful in hunting large wild animals throughout North America. The initial developers of the Clovis point held no patent, and may have used the design as part of an intentional effort to spread a particular culture across different tribes and language groups. Paleo-Indian technology was widely imitated as hunters and gatherers ranged across fields and forests throughout that part of North America not covered by the Laurentide Ice Sheet.

Clovis and other point styles from the Paleo Period

Source: National Park Service, The Earliest Americans Theme Study

Because we find essentially the same style of point in many different locations, it appears that bands of people traveled widely and interacted with each other regularly. Archeologists recognize differences between types of fluted points crafted in different places over the three-four centuries that the Clovis design was popular.

The rapid adoption of the Clovis point design would not have been possible if Paleo-Indian groups lived in isolation from each other by separate languages or hostile behavior. There must have been physical and cultural barriers, but at least in the Clovis period they were not high enough to cause separate, independent technologies to be restricted to certain locations.

Some caches of unused and unusually large Clovis points appear to be ceremonial stones rather than functional spearpoints. The design may have been associated with a spiritual belief that spread different groups with ritual hunting of mastodons, and the technological advantages of the Clovis shape for killing big game may have been less important in its rapid spread.14

As one author noted:15

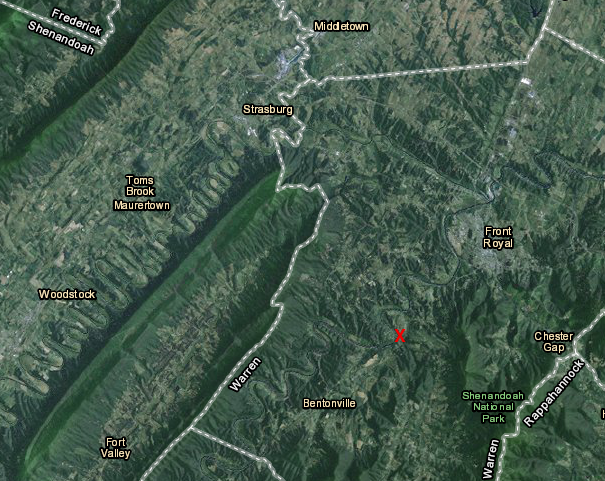

Archeologists have identified specific quarry sites from which Paleo-Indians extracted stone to make tools such as Clovis points. For thousands of years, groups regularly visited the jasper outcrop near Flint Run, on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River in Warren County. The quality of that stone for manufacturing replacement points, knives, scrapers, and other stone tools for another season of hunting and gathering was work the trip.

It appears some people even stayed there. The oldest known structure in Virginia - perhaps a house, perhaps a tool-making factory - was found at the Thunderbird site designated as 44WR11. Dr. William Gardner and his wife Dr. Joan Walker excavated the site for 15 years, starting in 1971. The National Park Service designated the Thunderbird Archeological District as a National Historic Landmark in 1977.

Close examination of a point discovered at Thunderbird showed evidence that it had been used on some form of cat, perhaps a saber-toothed tiger. Points found at the nearby Fifty Site showed evidence of rabbit and bear. Paleo-Indians in Virginia hunted far more species than just mastodons.16

Thunderbird is the only identified Paleo-Indian site where public visits have been encouraged. For several years a museum and archeological park located at the site provided public education, but the museum is gone. The archeological site is now subdivided and surrounded by modern houses. After excavations were completed, four lots were purchased by Archeological Society of Virginia and are the only part of the 1,800-acre site now protected by easement.17

the Paleo-Indian Thunderbird quarry is located on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

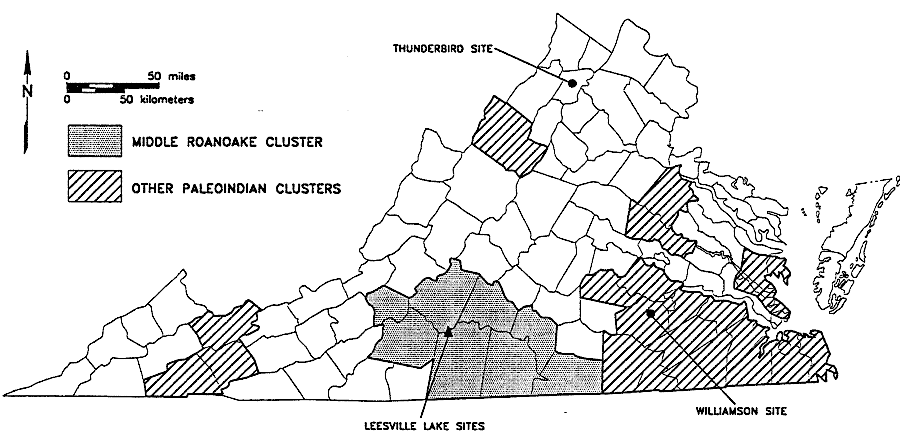

Paleo-Indians in Virginia developed other quarries besides those at Thunderbird. The chert outcrop at the Williamson site in Dinwiddie County supplied "Cattail Creek Chalcedony" for the bands hunting in what is now southern Virginia.

The jasper outcrop at Brook Run in Culpeper County may have been discovered and utilized by Paleo-Indians as well. We find evidence from just later periods at that site, but the evidence of the first users of that stone may have been destroyed by the continued extensive quarrying in the Archaic Period.18

Paleo-Indians developed "point" designs other than Clovis. Shafts and handles were made from bone and wood, so only the points of weapons used for hunting and for fighting other people have survived for later discovery by archeologists.

18,000 years ago at the Last Glacial Maximum, the edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet was at least 150 miles north of the Potomac River and deciduous forests thrived in Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Each hunter may have made some sort of fiber/skin basket or backpack to carry their gear from campsite to campsite, before lightening the load and carrying only selected weapons for an actual hunt. They may have worn a wristband with a part of an antler attached, which they used to re-sharpen a knife or point by quick percussion strokes.

Paleo-Indian camping gear would have included specialized stone tools, used for specific purposes. They carried spearpoints to kill animals, knives to cut a carcass into chunks that could be carried back to camp, scrapers to separate flesh from skin to make clothing, and awls to drill holes in skins before sewing pieces together.

The stone/shell/bone/wood tools would have been wrapped in fiber/skin "wallets" or sacks, in part to leave the traveler's hands free but also to prevent damage to the sharp edges of the tools. People packed carefully, though lightly, to avoid damaging their stone tools during transport.

Paleo-Indians could chip off a stone flake for one-time use in just seconds, but it took precious time to create a sharp edge on a specialized tool. The first people in North America spent the majority of their time, perhaps 80%, hunting and gathering their next meal. Points were re-sharpened as needed, and new tools were made constantly as wear and tear blunted edges. By one estimate, a family group used roughly 100 pounds of stone annually.19

"Food security" was low, so ecological sensitivity was high. Paleo-Indians were skilled geologists as well as skilled wildlife biologists, botanists, meteorologists, etc. They were able to distinguish the high-quality lithic materials of cryptocrystalline stone (jasper, chert, chalcedony, and other silica-rich rocks), forms of quartz that chipped easily and held a sharp edge longer.20

Some stone was acquired from specialized quarry sites, including the Thunderbird Quarry on Flint Run near Front Royal. Often, tools were manufactured from whatever was available when it was needed during seasonal travels into different habitats. For simple tasks, perhaps slicing up a carcass for a meal, a rock could be found, shaped, used, and discarded. Only the specialized tools, made from preferred rock types, were worth carrying around from place to place.

excavations at a former sand-mining site at Cactus Hill (Sussex County) documented that the first people in Virginia arrived before Clovis technology developed

Source: Center for the Study of the First Americans

Cactus Hill, which may be the oldest known site occupied by humans in Virginia, was discovered at a sand-mining operation in Sussex County

Source: GoogleMaps

18,000 years ago, Virginia was far from the edge of the ice sheet. There was vegetation everywhere, providing food for wildlife and the newest species to arrive. The landscape was not comparable to the modern Hudson Bay area. In Virginia, there was not a treeless tundra stretching to the ocean. In the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, there was more of a grassland environment with a steady and cold northwest wind blowing from the ice sheet. In contrast, more-sheltered river valley were warmer and rich in trees.

Hunting bands killed moose, elk, caribou, bison, and deer in the open grasslands created by lightning and mixed woodlands with patches of spruce, fir, and deciduous trees. Wild game may have been limited on the wind-swept mountaintops or mountain slopes with just a few scattered trees, but river valleys in Virginia were filled with pines and deciduous trees at the end of the Ice Age.

In Northern Virginia, where hills provided shelter from the cold and dry winds blowing off the ice sheet, chestnut, oak and hickory trees produced an annual supply of nuts that fed both wildlife and humans. Further south, the percentage of fir, spruce, and pine trees in the forest was lower. Deciduous forests covered the landscape, including a Coastal Plain 40 miles wider than today.

Paleo-Indians discovered habitats in Virginia that included open grasslands and forests with a mixture of spruce, fir, pines, and deciduous trees

Source: The State Museum of Pennsylvania, Archaeology, Paleo-Indian Diorama

Virginia's first hunters probably spent much of their time in the river valleys and lowlands such as the Shenandoah Valley, where the diversity of habitat offered opportunity to hunt rabbits, birds, and other small game. Constant movement enabled the Paleo-Indians to find new herds of large (and small) mammals, as well as to gather some wild seeds and fruits.

They also hunted or scavenged mastodons that had managed to remain in Virginia as the climate changed. What could be a tool manufactured from the tibia bone of a musk ox has been excavated at Saltville, from a site where a single mastodon may have been butchered and burned 15,000 years ago.21

Bones of a butchered mastodon have also been found near Yorktown. Because the arm and leg bones are missing, paleontologists suspect Paleo-Indians took the meat-rich appendages away to their campsite.22

Elsewhere in the Southeast, it is clear that Paleo-Indians hunted large game before the Clovis point was developed. Between 11,000 and 13,000BCE, they killed and cut up a mastodon on the edge of a pond at the Coats-Hines archaeological site south of Nashville, Tennessee. There is also clear archeological evidence that humans killed a mastodon 14,550 years ago at the Page-Ladson site on the Aucilla River in Florida. That was roughly 1,500 years before the Clovis point was developed, and 2,000 years before mastodons went extinct in the area.

Extinction of the mastodons at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch may have occurred even without human hunting pressure, as a result of climate change. However, some species such as mammoths, horses, and saber-toothed cats may have been hunted heavily enough during the Clovis Period to cause extinction. The 13,000-year old bones of an 18-month old boy excavated in Montana, labelled as Anzick-1, indicate that 40% of his mother's diet came from mammoth meat.

The extermination of the megafauna, such as mammoths, may have occurred in three phases:23

hunting party killing a mastodon, perhaps for ritual more than meat

Source: National Park Service, "The Earliest Americans Theme Study - Northeast Property Types," Paleo Time Period

The stereotype of the first Virginians being big-game hunters, traveling great distances in small hunting parties and spearing mammoths/mastodons for a meal every week, may be completely inappropriate for Virginia and even elsewhere in North America. Because the Clovis points were large, there was assumption that it was used to hunt large mammals. The Big Game Hunting hypothesis has now been supplanted by an assumption that:24

Killing a mastodon may have required separate family groups to unite in the effort, and there were easier sources of food that exposed hunter-gatherers to lower risks. A megafauna kill could have been a rare ceremonial event with great social and symbolic significance rather than just a routine hunting exercise. It is possible that the Clovis point was not able to penetrate the hide of a mammoth, and was used primarily to butcher rather than to kill large animals.

If mastodons in Virginia were not hunted primarily for food, one possibility is:25

The Paleo-Indians interacted with other family groups, traveling great distances to obtain food. It is unlikely that different groups had well-defined hunting/gathering territories. Similar to modern humans, Paleo-Indians were social animals seeking the company of others for trade, marriage partners, and entertainment.

based on where Clovis points have been found, that shape may have been developed initially in eastern North America and spread westward by cultural diffusion

Source: Paleoindian Database of the Americas, Maps - Entire Database Sample

Population levels were low, based on the small number of artifacts recovered from the Paleo-Indian Period compared to the later Archaic Period. Less than 100 Paleo-Indian sites have been located in Virginia.

During the Paleo-Indian Period within Virginia, different small family units with shared family connections may have gathered into microbands of about 25 people. Within Virginia, there were at least three macro-bands numbering 175 to 475 individuals during the Clovis Phase. For special hunts of large game, microbands may have gathered into two to eight large macrobands. The total population of Virginia may have been 250-500 people at 8,900BCE, growing to 725-1,450 people at the end of the Paleo-Indian Period around 8,000BCE.

Initially, groups may have been widely separated, each ranging across an average of perhaps 80 square miles on regular "seasonal rounds." At that sparse density, there would have been just 500 bands with just 5,000-10,000 people hunting and gathering across all of Virginia. They would have arranged to meet at designated spaces at specific times, to trade and allow maturing children to form family units.

There is no archeological evidence that shows Paleo-Indian hunters were predominantly male while those gathering fruits, nuts and plants were predominantly female. Assumptions about gender-based roles may reflect the perspectives of modern anthropologists. There are also logical assumptions that females were less muscular, mothers were responsible for nursing/child raising, and gathering involved less risk than hunting, so gender-based roles in a Paleo-Indian band would be advantageous.

Gathering nutrients requires more time than killing animals. The stomachs and intestines of animals provide carbohydrates and other nutrients derived from plants, so having both males and females participate in hunting expeditions would increase the number of humans stalking animals and increase the potential for success.26

Microbands did not roam at random, looking for food. Some may have engaged in a seasonal round, seeking food in certain places at roughly the same time each year.

Paleo-Indians moved constantly to find new food resources, but bands returned to some places seasonally or to quarry new stone for their toolkit

Source: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Paleoindian Period

At least some demonstrated "tethered nomadism." Microbands or family units came back to a few, highly-preferred quarry sites whenever their toolkit was depleted. Such return visits might occur at any time of the year.

After quarrying more flint and jasper, they would pause long enough at a site nearby to make a new set of points, knives, awls, scrapers, etc. Worn-out tools could then be discarded at the site where new tools were manufactured. When enough stone knapping had been completed, the local food resources exhausted, or rivals appeared to conduct their own resupply operation, the microband or family group would return to its pattern of hunting and gathering.

It is clear that Paleo-Indians regularly excavated at Flint Run and Williamson quarries to extract their preferred cryptocrystalline stone. The quarries were rare sources of chalcedony, chert, and jasper, forms of silica like quartz, that made sharp edges when shaped skillfully through percussion (hammering to crack off large pieces) and pressure (to remove smaller, specific flakes). There is evidence that 20 different groups used separate spots at Flint Run for collecting and processing the stone to restock their tool kit.27

Each Paleo-Indian band included roughly 25 members. Groups who lived together were based on close family connections; only later would different families share the same space and develop into tribal groups.

The initial interactions between bands of strangers armed with spears and razor-sharp stone knives must have been stressful, but the need to find mates outside the family would have spurred regular social interaction. When groups met, it is reasonable to assume they traded information and also special objects, such as shiny shells and stones preferred for making tools. The "first date" between adolescents in other hunting bands would have been followed by a quick decision to select a mate, before the bands traveled in different directions for perhaps another year.

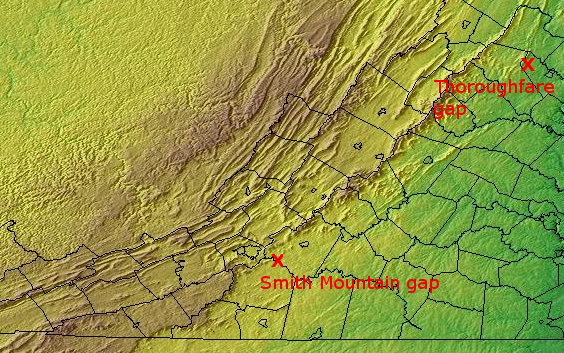

The roaming macro-bands (groups larger than single families, but not organized into tribes independent of family kinship) may have used gaps through the Blue Ridge as the geographic locators of where to meet. Groups roaming through the valleys west of the Blue Ridge might make repeated visits to the eastern edge of the mountains, or groups roaming on the Piedmont might push westward through a wind/water gap to meet other macro-bands.

Paleo-Indians may have used gaps in the Blue Ridge as easy-to-recognize locations for meeting with other traveling bands

Source: Global Land One-km Base Elevation Project (GLOBE), State Topography Image: Virginia

Former Fairfax County Archeologist Mike Johnson has suggested that Paleo-Indians may have used Smith Mountain Gap (Pittsylvania County) and Thoroughfare Gap (Prince William County) to specify "meet-up" sites. On some pre-arranged date, perhaps defined by cycles of the moon, separate bands would gather for a few days to trade, socialize, and find new partners. Negotiations had to be concluded before local food supplies were exhausted and the bands set off in different directions, after arranging the time and place for a future rendezvous.

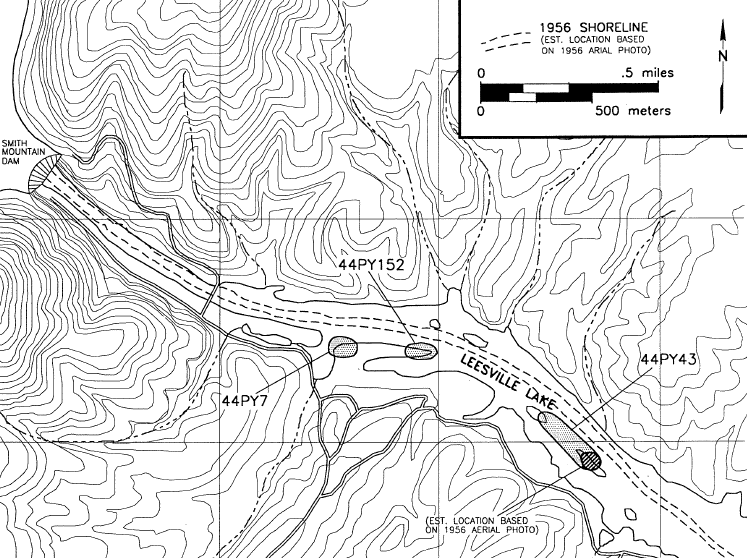

Some of the oldest human-created artifacts in Virginia have been revealed at excavations at the eastern edge of Smith Mountain Gap, on the eroding shoreline of the pumped storage hydropower reservoir between Smith Mountain Dam and Leesville Dam. That location provided an easy-to-identify slot in the Blue Ridge, recognizable from as far as 30 miles away on the eastern side. Before the Roanoke River was dammed, anadromous fish such as Atlantic salmon swam far upstream to the rapids there, providing a key protein source for a rendezvous there in April-June.

Paleo-Indians returned to sites on the Roanoke River, later inundated by Leesville Lake

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Archaeological Assessment of Sites 44PY7, 44PY43, and 44PY152 at Leesville Lake, Pittsylvania County, Virginia (Figure 9)

Travelers from the east could have brought brightly-colored shells from the Atlantic Ocean, located 40 miles further east from the current shoreline. During the Ice Age, sealskins were readily available at the latitude of modern Virginia. Ocean-based items would have been especially valued by Paleo-Indians living west of the Blue Ridge.

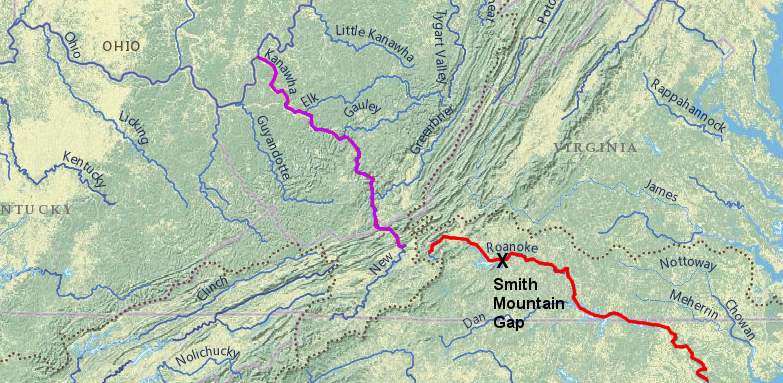

Travelers from the west could have brought trade items from the Mississippi River valley. One of the easiest routes to the Piedmont of Virginia from the Ohio River Valley was to walk up the Kanawha River to the watershed divide between the New River and the Roanoke River. Near Blacksburg, Paleo-Indians could cross into the headwaters of the Roanoke River and reach the distinctive landscape feature, the Smith Mountain Lake gap.

Perhaps the item of greatest interest for trading at a rendezvous would have been different forms of stone. Skilled knappers could get new blocks on raw material that they could shape into tools, or alter to create effigies. Paoli chert from the Big Sandy River drainage in Kentucky has been identified at Leesville Lake. Clearly Paleo-Indians transported it there for a reason; that form of chert could not have been carried naturally by a river from Kentucky to the gap.28

Smith Mountain Gap offered a meeting spot in Paleo-Indian times for travelers from moving east up the Kanawha/New rivers (in purple) and west up the Roanoke River (in red) to trade sealskins, seashells, and unique forms of stone

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The predictive model allows archeologists to target specific sites for research, rather than rely upon chance discovery. Specific criteria entered into a Geographic Information System (GIS) can suggest where, 10-15,000 years ago, traveling bands of hunters would have said "let's meet there, to trade and party" at a particular time of year.

Even without GIS technology or archeological expertise, it is possible to recognize distinctive locations. For example, a sandstone outcrop offering a spectacular view from the west side of the Blue Ridge near the Loudoun/Clarke county line known as Bears Den may have been a gathering point.

Paleo-Indians may have walked from the Shenandoah River to Bears Den, following the topography the way Route 7 does today

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The first Virginians moved often through the course of a year. Groups living near a source of stone for their tools (Paleo-Indian quarries) may have traveled less than groups living on the Coastal Plain, where there were fewer rocks that were easy to fracture into tools that held their sharp edges. Paleo-Indians in Virginia probably:29

On Spout Run near the Shenandoah River in Clark County, an archeologist has claimed that a series of concentric stone circles (designated site 44CK151) could be a 12,000-year old observatory. Jack Hranicky hypothesized that Paleo-Indians, after quarrying jasper for tools at Thunderbird, walked down the Shenandoah River and held some sort of cultural ceremonies at the Spout Run site.

Petroglyphs in the shape of foot prints could be intended to mark where to stand in order to observe an equinox - or the arrangement of the rocks could also be natural, with alignments created by just gravity and erosion over time. If it was built in the Paleo-Indian period to mark the summer/winter solstices and fall/spring equinoxes, the Spout Run site is unique.

Modern scholars have identified only one other possible solar observatory in Virginia. Hand glyphs in a rock shelter at Little Mountain in Nottoway County are illuminated by sunlight only around the winter solstice. The relationship between sunlight and that rock art, painted much later in the Woodland Period, may be just coincidental.

It would always be a challenge the accept that humans arranged the rocks at Spout Run over 10,000 years ago to create a solar observatory, but constructed at most one other calendar site in all the remaining time before European colonization.

Perhaps there are more prehistoric calendar sites in Virginia. They could have been disrupted by farmers who occupied the lands in the 1600's and 1700's, or perhaps modern archeologists have just failed to see the evidence. There is no reason to assume that cultural changes at the end of the Paleo-Indian period included the loss of astronomical understanding.30

The end of the Paleo-Indian period, and the start of the Archaic period, is marked by new designs of points. The distinctive fluted point, with the flake removed from the center, is replaced by notches on the side. That may reflect a different technique for attaching the point to a wooden shaft.

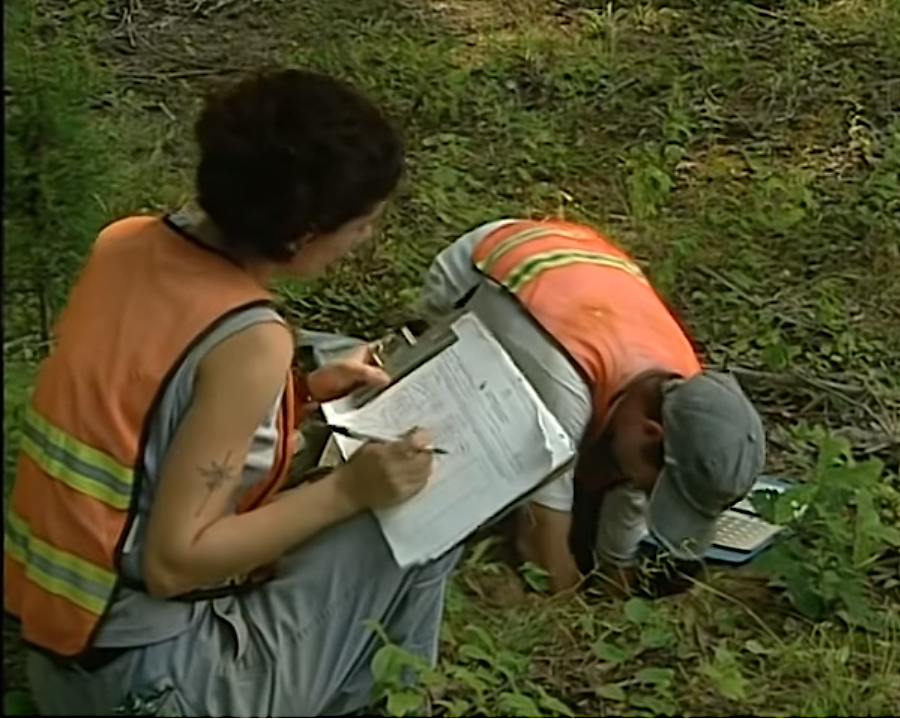

archeologists search for stone and pottery evidence of early Virginians by excavating small sample locations based on a mathematical grid (shovel testing)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

Around 8,000BCE, human travel and settlement patterns were affected by the emergence of new habitats and new food sources. In Virginia, large mammals such as the mastodon were replaced with deer and other smaller game animals. Deciduous forests replaced open grasslands, offering nutritious hickory nuts and even acorns. Estuaries on the Coastal Plain stabilized, followed by an increase on accessible oysters, clams, and crabs. Anadromous fish swam up river valleys to the Fall Line, offering yet another source of protein and fat.

Changing habitats may have encouraged foraging in more areas, expanding the number of ridgetops and valleys visited by hunting and gathering parties. as people moved into areas formerly unoccupied, family groups may have become more isolated. Interaction between groups may have been blocked by evolving religious or political barriers, and the emergence of separate languages.

Finding different designs in different locations that were occupied at the same time period suggests that the occupants of those two places were isolated by physical or cultural barriers, allowing time for flintknappers in different groups to evolve separate styles. Access to the Thunderbird quarry may have been limited by new boundaries between foraging groups that emerged about 10,000 years ago.

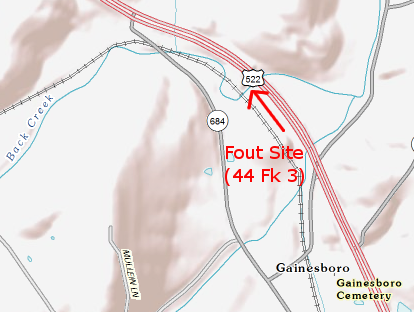

That constraint could have spurred a hunting band to use chert from Back Creek, north of modern-day Winchester. A workshop location where chert was reduced to cores and some finished points, later labeled the Fout Site, was destroyed when the Virginia Department of Transportation expanded US 522. The site was excavated by archeologists before the highway bridge over the creek was built, though the information from the 1969 dig was not finally published until 1996.31

Fout Site (44 FX 3), a chert quarry workshop first used in Early Archaic Period

Map Source: US Geological Survey, National Map

The presence of a significantly new stone tool or pottery design in a location could also suggest human migration. New designs may appear quickly, without gradual changes in the preceding design, when a place is occupied by a new group. Immigrants bring new cultural patterns.

By tracing the locations of archeological sites with a specific design, it is possible to show the migration paths of the past. In the Paleo-Indian Period, groups interacted often enough to have a standard way of making Clovis, Dalton, and Cumberland points across all of Virginia.

meticulous documentation is as important as finding artifacts, to identify patterns of living in the past

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

In the Archaic Period, the Native American population expanded. Greater diversity in point styles suggests that boundaries between different groups of people became more firm, limiting long-distance travel of individual hunting/gathering bands. New points were smaller and had many with notches on the corner, where sinew and plant fibers were wrapped to attach the point to a smaller spear or an atl-atl projectile.

Media stories occasionally suggest the organized bands of Paleo-Indians have survived intact to modern times. For example, one 2018 story about the Pamunkey proposing a gambling casino began with "They've survived in Eastern Virginia for more than 10,000 years..."32

Native Americans but not tribal polities have been in Virginia for 10,000 years. Modern tribes such as the Pamunkey evolved after the introduction of agriculture 1,000 years ago, when the hunting and gathering bands of the Archaic Period became more sedentary and constructed permanent towns.

In the Archaic and then the Woodland Period, groups organized and re-organized into different tribal identities and allegiances, with three major language groups in Virginia. The distinct, individual tribal identities that the Europeans encountered in the 1500's and 1600's may have crystallized only after Hernando de Soto disrupted Native American societies in the mid-1500's.

Had the English not colonized Virginia in 1607, Powhatan's paramount chiefdom might have evolved into a more-centralized state, dissolved during a period of environmental stress, or been conquered by the Iroquoian-speaking tribes which formed the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Native American cultures and political alignments were as dynamic and as fluid as the cultures and political alignments in Europe over time. The boundaries of Virginia as a political unit, and the people who identify themselves as "Virginians," have changed substantially over the short 450 years since a region in North America was named for an English queen.

No individual band has maintained a distinctive identity as a "tribe" for 10,000 years, from the Paleo-Indian Period until today. The shapes of points chipped from stone changed, and three major styles evolved in Virginia during the Paleo-Indian period:33

Source: cf-apps7865, Cactus Hill & Brook Run ~ 18,000(!) Year Old Virginia Sites

edge of the Atlantic Continental Shelf, where first Paleo-Indian camps may be located underwater today (36° 30' is the latitude of the southern border of Virginia)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

principal Paleoindian artifact clusters in Virginia, as identified in 1994

Source: Archaeological Assessment of Sites 44PY7, 44PY43, and 44PY152 at Leesville Lake Pittsylvania County, Virginia (Figure 44)