the invention of pottery enabled better food storage, but heavy pots made sense only in a society that occupied one place for long periods of time

Source: National Park Service, Southeastern Prehistory - Middle Woodland Period

the invention of pottery enabled better food storage, but heavy pots made sense only in a society that occupied one place for long periods of time

Source: National Park Service, Southeastern Prehistory - Middle Woodland Period

The climate and the environment in Virginia changed at the end of the last Ice Age, 18,000 years ago. Native Americans responded by changing their technology for hunting, placing smaller points on their spears and hunting smaller game as the large mammals disappeared and deciduous forest expanded to cover Virginia. That shift in Native American culture is defined today by archeologists as the shift from Paleo-Indian to Archaic.

The shift from Archaic to Woodland is also defined by new technology and new patterns of behavior. The Woodland label marks a distinctive evolution in Native American culture that evolved from internal reasons. That cultural change probably was not triggered by a major shift in climate, in contrast to the change between Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods.

Archaeologists distinguish the Woodland period from the preceding Archaic period by adoption of agriculture (ultimately including corn) and widespread adoption of pottery. The switch from hunting with a spear (including those thrown with an atl-atl) to hunting with a bow and arrow came in the middle of the Woodland Period. In Virginia, the Woodland Period (after the Archaic Period, and before European contact) lasted from 1200BCE to 1600CE.

Native Americans made lightweight "points" from bone as well as stone tools

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Bone Weaving Tools and Projectile Points, Early Woodland Stone Tools

Agriculture gradually replaced more and more of the hunting and gathering of food during the summer months. Groups of people began to occupy houses in one location for a longer part of the year - presumably between the time crops were planted and harvested.

People on more-sedentary communities began to use pottery. Pottery and its precursor, soapstone bowls, facilitated cooking of food directly within the fire or by putting hot stones into skin/bark sacks. Heavy soapstone bowls were not suitable for carrying on long hunting expeditions, but quite useful if a group of people stayed in one place. Clay pots were fragile, equally unsuitable for travel but valuable for constant use at a settlement.

The bow-and-arrow (with smaller stone points that can legitimately be called "arrowheads") replaced the spear and atl-atl, the "throwing sticks" of the Archaic period.

Key cultural changes appear to have occurred in southern Georgia and the Ohio River Valley first. The changes were imported into Virginia either as people migrated directly into Virginia, or as new ideas were transmitted gradually between groups of people living near each other.

Cultural shifts in Virginia can be attributed to both migration and diffusion. Rapid changes may reflect immigration of a new group of people after conquering territory and displacing the previous residents. Another possibility is that the residents were the conquerors, and brought back captives who introduced new technology such as making pottery with a different material used for "temper." Slow changes, with the speed of change interpreted by the age of artifacts recovered by archeologists, may reflect diffusion of culture during long periods of trading and intermarriage.

The Woodland Virginians left no written records; cultural diffusion never brought the writing invented by the Maya to people living north of Mexico. Through archeology, we know the Native Americans in Virginia after 1000BCE preferred the same locations as later emigrants from Europe - river bottoms where crops could be grown on flat, fertile ground.

archeologists depend upon organic stains in the soil to identify the locations of structures, such as palisade walls

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Native American Settlement at Great Neck (Figure 11)

Little evidence of their lifestyle has been protected from later disturbance in the fields that were plowed by late-arriving English, Scotch, and German settlers. Even isolated shelters in the mountains have been used by modern day hunters and hikers, disturbing the archeological evidence and contaminating sites with modern charcoal.

We do find enigmatic symbols preserved in a limestone cave at Paint Lick Mountain in Tazewell County. Someone drew figures on the wall, creating geometric designs as well as shapes of humans and animals, using fingers dipped in red pigment. We can date human occupation at the site because charred remains of wood on the cave floor were 1,000 years ago. When or why the pictographs themselves were drawn remains unknown.

The one other rock art site in Virginia is also thought to date from the Mississippian Period. Three hand glyphs were painted inside a rock shelter at Little Mountain in Nottoway County. Because the hands are in shadow except during the time around the winter solstice in December, the rock art may be related to a solar calendar of some sort. Today we understand less about those symbols that we do about the glyph chosen for the singer formerly known as Prince.1

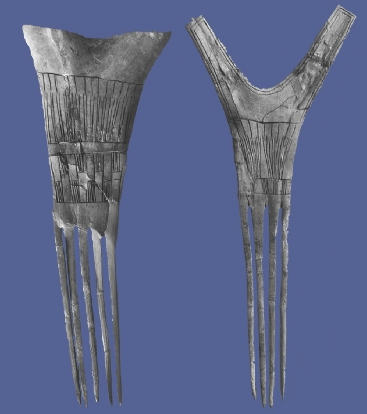

combs carved from antlers, found at Bowman Mound near Linville (Rockingham County)

Source: National Park Service, Rock Creek Park: Prehistoric Landscapes of the Nation's Capital

Pottery developed initially in the southeast, between northern Florida-North Carolina (perhaps initially near Stallings Island on the Savannah River), before it appeared in Virginia. The earliest forms of pottery in Virginia showed a transition from the older soapstone bowls. The Bushnell Ware and Marcey Creek Ware forms of pottery, dating back to 1000BC, included ground-up bits of soapstone in the clay as a "temper" to minimize the cracking of pottery as clay was heated in a fire. Later forms of pottery used ground-up mussel/oyster shells or sand as a temper, eliminating reliance upon access to soapstone quarries.2

French explorers found massive mounds at Cahokia (les Chateauex runinez - "the ruined cities"), relics of the Mississippian culture

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Louisiane et du cours du Mississippi (1718)

In the late Woodland Period, Southwest Virginia was affected by the Mississippian culture, which thrived between 1000-1400CE in the Mississippi River Valley. A distinctive feature was construction of massive earth mounds, with temples and housing for the rulers on top. Inside many mounds were graves, presumably a place of honor for people who were considered special in some way.

Some combination of religious zeal and imposed power spurred people to load 20-40 pounds of soil into baskets and carry them as much as 100 feet uphill. On hot summer days, it would have been exhausting work to zig-zag up narrow steps carved into the sides of the growing artificial mountain, dump a basket where directed by a prehistoric engineer, and then return for another load.

At the top of the mound was a unique and powerful vista enjoyed by just a few people. At the bottom of the mound was a hierarchically structured society that reflected strong control by an elite, who benefited from the labor of many others. Most of the mound builders spent their time in the area scraping and hauling dirt, building palisades, growing food, processing meals for the workers, and keeping the construction site sanitary.

construction of mounds required an organized society, with a labor force motivated by some reason to carry 40-pound baskets of dirt uphill in a monotonous routine

Source: National Park Service, Ancient Architects of the Mississippi

The city of Cahokia developed across the river from modern St. Louis between 700-1400 CE, and may have been the largest prehistoric Native American city north of Mexico. There were 120 mounds, so it was a probably a permanent construction site. Around 900 CE, people moved a five-ton tree over 100 miles to the norh to Cahokia to serve as a marker post.

Some specialists estimate Cahokia had a population of 10-20,000 people at its peak around 1100CE. Others estimate 40,000 people, and in 1250CE Cahokia may have had more residents than London. At the bottom end of population estimates, the population may have been closer to 3,000-8,000, with residents steadily building the mounds by contributing several weeks of work each year.3

The Mississippian culture edged up the Tennessee River and Kanawha River watersheds into Southwest Virginia. It first arrived about 2,000 years ago, long before the creation of Cahokia. The expertise to domesticate plants, first developed in the Mississippi River Valley, may have been the trigger for transforming societies. The once-egalitarian bands of hunters and gatherers evolved into stratified societies, with social and economic gaps separating the elites from ordinary workers. One group arrived at the Carter Robinson site around 1250CE, built a mound about 75 years later, and left after another 75 years.4

During the Mississippian Period, people lived in towns controlled by chiefs. Society was structured into two classes, with elites and commoners. The gap between elites and ordinary people is recorded in the gravesites of the Mississippian period. The elites were buried in earth mounds, which are believed to have been constructed by the ordinary workers.5

Ely Mound is one of three mounds in Lee County that may have formed a city complex. It was excavated in the 1870's. At that time the mound still had the rotting cedar posts of what may have been a building used by tribal leaders of that area. Ely Mound is about as close to Monticello or Mount Vernon as you can get, for that now-vanished culture.

only a remnant of Ely Mound remains today, near Rose Hill in Lee County

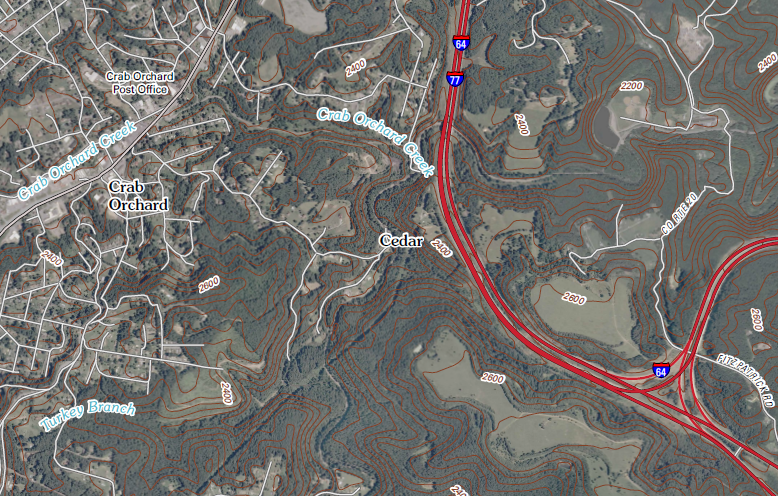

Around the time Columbus set out to find trading opportunities in Asia and ended up proving the earth was round, the residents of what would become Tazewell County build a palisade around the town at Crab Orchard. The palisade was a series of tall poles stuck in the ground, one next to the other, to either keep enemies out or animals in. Inside the palisade were houses made on saplings and covered with bark and/or skins, storage pits for food, and burial pits. A gate house would sometimes be built to guard the entrance through the palisade.

Crab Orchard (Tazewell County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Crab Orchard 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2011)

Burial mounds were also constructed further north, in the Shenandoah Valley and the Piedmont. Tools were made from local materials, with use of quartz in the Piedmont but chert/jasper in the Shenandoah Valley and Blue Ridge.

The distinctive burial mounds, now largely removed through plowing and floods, held the remains of hundreds of Virginians, including the bones of many that were ritually reburied there. The mounds grew larger over time, as more and more people were buried in them, comparable to the Hopewell culture burial mounds.

One of these mounds was excavated by Thomas Jefferson in 1784 along the Rivanna River. This was after he had retired as Governor of Virginia, the Revolutionary War was over (Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown in 1781), and Jefferson was living the life of a "scientific" country gentleman.

forks of the Rivanna River today (Albemarle County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Charlottesville East 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2011)

Jefferson dug perpendicular into the "barrow" and found bones on the bottom. It was covered by a layer of stones brought from a cliff a quarter-mile away, covered by more earth, more bones, etc. in three separate strata. He estimated 1,000 skeletons were in that one mound. At the same time, he estimated the population of living Indians in Virginia, indicating how he thought the Virginia tribes were losing their distinctive character through demographic change:6

The earliest English settlers may have met two tribes that built such mounds, the Manahoac at the Falls of the Rappahannock and the Monacan at the Falls of the James. They spoke languages based on a Siouan rootstock, rather than the Iroquoian languages south of the James River or the Algonquian languages of the coastal tribes.

John Smith identified tribes beyond the Fall Line

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith

At the start of the Woodland Period, bands of hunters and gatherers were probably based on family groups. The food supply increased with the adoption of agriculture, and people settled at places with good soil and water. Annual harvests would not guarantee enough food to last for a year until the next crops ripened, so hunting and gathering was a major source of food during the winter and spring months.

About 1,000 years ago, the best places for growing corn became places that were worth defending against rivals. Groups expanded to include multiple families, since a larger population provided greater security. Assembling more workers also enabled building palisades around towns. Building defensive infrastructure required much labor, since cutting trees and digging holes was done with stone tools or use of the wheel. Logs were moved without draft animals such as horses.

Around 1300 CE, a period of global cooling known as the Little Ice Age triggered a new settlement pattern. The power of the elites who dominated Mississippian chiefdoms collapsed, perhaps as harvests failed and people lost faith in both political and religious leaders. New coalitions and confederacies were established in the 1500's and 1600's as neighbors formed alliances that Europeans identified as Iroquois, Choctaws, Cherokees, Upper and Lower Creeks, Shawnee, Monacans, Piscataways, and Powhatans.

Communities that had grown dependent upon agriculture migrated to river valleys with better soils and southern locations with a longer growing season, changing the size of towns:7

During the Woodland Period, everyone had a similar level of stone-based technology but different cultures evolved. Groups worshipped differently, built houses differently, and spoke differently. Virginia ended up with people speaking languages in Iroquoian, Siouan, and Algonquian language groups. Tribal governance varied. Cherokee towns were only loosely allied, and going to war required recruiting leaders in indivdual towns. The Monacans in the Piedmont, and the Piscataway and the Powhatans on the Coastal Plain, established paramount chiefdons with a more-centralized form of government.

The first Europeans met by Virginia's Native Americans were sailors. Most ships in the 1500's that stopped along the Virginia coastlines had Spanish captains, but the mariners were a mixture of many cultures. The first black Africans to be seen by Native Americans in Virginia were probably sailors on those ships.

During the initial contact period, European ships provided metal tools and prestige objects. Shoreline towns along the Chesapeake Bay may have welcomed their arrival, though some people were kidnapped and taken away. The sailors knew they would be returning to Europe, but the captives had no previous experience of an ocean view with no land in sight. The captives must have been in shock during the trip. Those who survived and reached Europe discovered a dramatically different Old World with houses heated with coal, wagons pulled by horses, and mass concentrations of people in cities.

In the 1500's, the Native Americans had little resistance to new diseases. Coastal towns in Virginia were not exposed to much infection during the brief visits of the ships. By the time sailors reached Virginia, they had been traveling for so long that any who had tuberculosis, malaria, yellow fever or other contagious diseases when leaving port had either died or recovered.

Most people kidnapped in North America and taken to Europe during the contact period had a different level of exposure; few lived long enough to return. A rare exception was Paquiquineo, captured in 1561 and returned by Spanish colonists (as "Don Luis") to the James River in 1570.

Politics and cultural patterns of the coastal plain Indians are known best, including some reports from the Spanish adventurers who sailed to Virginia in 1525. Apparently the Europeans arrived about the time a political shift occurred, or triggered that shift.

Spanish expeditions in the 1500's trampled across Native American societies from modern-day Florida into North Carolina and Tennessee. The disruption did not directly affect groups living in modern-day Virginia, but the shattering and reconstitution of Woodland Period societies rippled across beyond the places actually visited by Hernando de Soto, Juan Pardo, and others.

Along the Coastal Plain a hierarchy of political and military power developed. Small, militarily weak tribes had to submit to dominant tribes, paying heavy tribute in exchange for peace and a measure of independence. Chief Powhatan's father may have assembled the first six tribes of his paramount chiefdom in reaction to the Spanish traveling through the Carolinas and their attempt to settle on the Peninsula in 1570-71, and in response to the stories shared by Paquiquineo/Don Luis.

By the time the English settlers moved inland across the Fall Line, into the Piedmont and the Shenandoah Valley, the impact of disease and/or attacks by the Haudenosaunee from the north and Cherokee from the south had dramatically reduced the population of tribes living on the Virginia Piedmont. With the exception of Jefferson's report, and negative assessments by the settlers crossing into their territory and planting their own crops in the openings in the woods created by the Indians, there is little about their lifestyles in the historical record.

In contrast, we have many reports about the natives who greeted the English in Tidewater. The Coastal Plain Culture was characterized by saltwater food resources, in contrast to the Indians above the Fall Line and in far Southwest Virginia. Shellfish like oysters, anadromous fish like the sturgeon and shad and striped bass, plus crabs provided reliable food resources and enabled towns to develop all along Tidewater rivers and creeks. Instead of burial mounds, the Coastal Plain culture created middens of oyster shells.

The lack of stone along the coast caused the Coastal Plain culture to rely more heavily upon tools made from bone, shells, and wood. However, trading patterns throughout North America brought copper all the way from the Great Lakes area, as well as corn, squash, and beans up from Mexico. Coastal tribes could trade for stone tools with groups living on the Fall Line or Piedmont, where Native Americans could quarry outcrops for stone. in addition, chert cobbles and other forms of quartz washing downstream provided raw material would not have been a challenge for the earliest Virginians.

meticulous excavation can identify patterns of artifacts and postmolds that reveal how Virginians lived prior to the arrival of the English colonists

Source: Werowocomoco Research Project, Werowocomoco: A Powhatan Place of Power

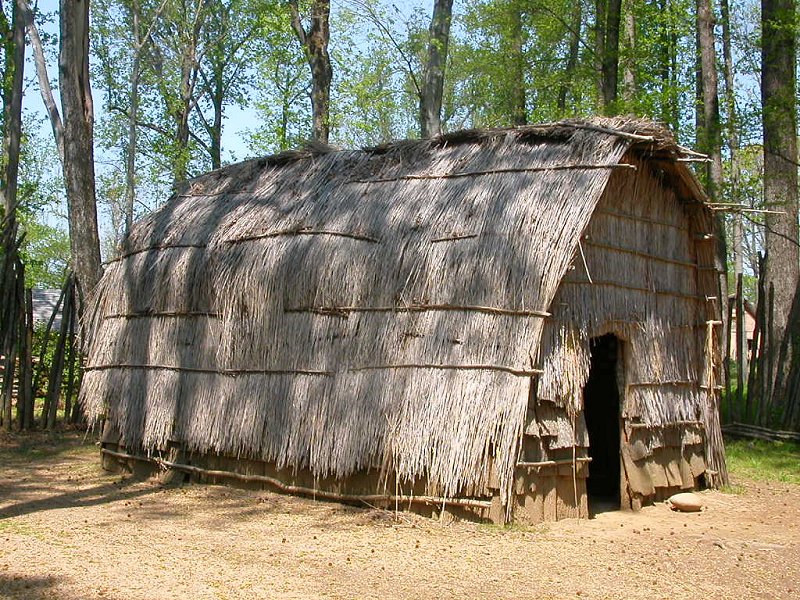

The towns of the Coastal Plain Culture were drawn by early European artists, so we have more than archeological stains in the dirt to deal with. The lodges were oval, covered with bark, and wouldn't pass today as even minimum quality housing. No running water, no indoor toilets, no phones, no cable TV - it was a different environment, and even the modern recreations are hard to get exactly right because the maintenance of the raw materials is time-consuming. Some were fortified towns surrounded by wooden palisades. They were built for protection, just as the English built a wooden wall around the first settlement at Jamestown.

Native Americans built wooden palisades where towns were threatened by rival groups

Source: University of North Carolina, Theodore De Bry Maps, Native American Village of Pomeiooc

One cultural practice recorded by the English colonists after 1607 was the huskanaw. A ritual marked the transition on young boys into men, a rebirth process that the English thought at times included actual death of the boys. Key to the ritual was a poisonous plant, Datura stramonium, known today as "Jimsonweed." All parts of the plant are toxic, and ingestion of the seeds in particular can cause convulsions, hallucinations, and even death. A psychoactive experience by the young boys during the initiation process led to their change in status, if they survived the experience with poison.8

The burial rituals of the first "First Families of Virginia" after the Mississippian Period were quite different than those we use in Virginia today. Sometimes they were buried in pits, but in other cases the dead were first left on high platforms where the flesh decomposed, or was eaten by birds and other animals. Then the bones were buried in pits (rather than mounds to the west). The bodies of the chiefs were treated differently. They were mummified and kept in lodges known as "quioccasans."

Today, in the suburban sprawl west of Richmond in Henrico County, there is a road called Quioccasin. On the Colonial golf course in Williamsburg, there is other evidence of prehistoric Virginia that was preserved when the golf course was built:9

interpreter explaining Native American canoe construction

with fire and scraping, at Jamestown Settlement

bark-covered dwelling structure, recreated to represent Siouan-speaking Totero in Valley and Ridge (Explore Park, Roanoke County)

reed-covered dwelling structure, recreated to represent Siouan-speaking Monacan in Valley and Ridge (Natural Bridge, Rockbridge County)

reed-covered dwelling structure recreated to represent Algonquian-speaking Appomattoc in the Coastal Plain (Henricus Park, Chesterfield County)

residents at Werowocomoco kept fires burning constantly inside their reed-covered structures

Source: National Park Service, Werowocomoco Planning

Native Americans in Virginia, unlike their counterparts on the Great Plains, did not live in teepees made of animal skins

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Comanche Village, Women Dressing Robes and Drying Meat (by George Catlin)