From Paleo-Indian to Woodland Cultures: Virginia's Early Native Americans

The first Virginians hunted elk, moose, deer, bear, bison (buffalo), wolves, perhaps even some mastodons and mammoths. Over the last 15,000 or so years, they developed or imported new tools, such as the atl-atl throwing stick and ultimately the bow-and-arrow, to accompany their earlier stone scrapers and points.

They adapted to dramatic climate change. They learned to domesticate plants and to fire clay to make pottery. They made canoes, floated the Virginia rivers, and even paddled across the Chesapeake Bay to the Eastern Shore.

The English colonists who arrived in 1607 considered the Native Americans to be "savages" with different religious beliefs, different customs when engaged in war, and different forms of dress. Those "savages" had greater skills than the European immigrants in understanding, exploiting, and adapting to change in the environment in which they lived.

the English discovered Native Americans with different forms of dress, but in this portrayal the bag around the waist looks like the sporran worn by Scots with a kilt

Source: LearnNC, Theodor de Brys engraving The Coniuerer (from Thomas Hariot's 1588 book A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia)

The cultural patterns of the first Virginians evolved substantially over time; technological change started long before the modern challenges of new computers and social media. The original small (perhaps just family-based) bands coalesced into organized groups capable of building large ceremonial burial mounds west of the Blue Ridge and in the upper Rivanna/Rappahannock river valleys. At the time of European arrival, one group of tribes centered along the York River was organized into what approximated a political state, with a paramount chief named Powhatan who exercised control over multiple tributary tribes.

The structure of Powhatan's organization was based on more than kinship ties, but it is a stretch to call Powhatan's government an "empire" comparable to the political units in Europe that sponsored voyages of discovery. Tribes paid taxes (tribute) to Powhatan; he was superior in authority over people not related to him. Powhatan had to consider the opinions of religious leaders and chiefs of subordinate tribes, but those tribes were ultimately controlled by one leader.

The Virginia Council of Indians advises:1

- Powhatan's tributaries (the tribes that paid tribute to him) are best referred to as a "paramount chiefdom" or "paramountcy."

Up the Potomac River near the Fall Line, the Piscataway tayac based in modern-day Maryland governed multiple tribes, including the Moyumpse (Dogue) in Virginia living between the mouth of the Occoquan River and modern-day Mount Vernon. George Washington built his grist mill on Dogue Creek.

At times, the Patawomeck living at the mouth of Potomac and Aquia creeks were more closely allied with that tayac across the Potomac River, rather than with Powhatan on the York River. In 1607 there was no "empire" controlled by either Powhatan or the tayac. Though both spoke Algonquian languages, there was no Algonquian "confederacy" in Eastern Virginia; Powhatan and the Piscataway tayac did not share authority. They were rivals, competing for power at the edge of their territories.

The individual leaders who controlled kinship-based towns and tribes also competed for prestige and power. Competition was between tribal leaders, and with the paramount leaders too. Resistance to Powhatan's control is indicated by the location of so many towns north of the Rappahannock River. That river was a dividing line between Native Americans long before King Charles I made it a boundary of the Fairfax Grant.

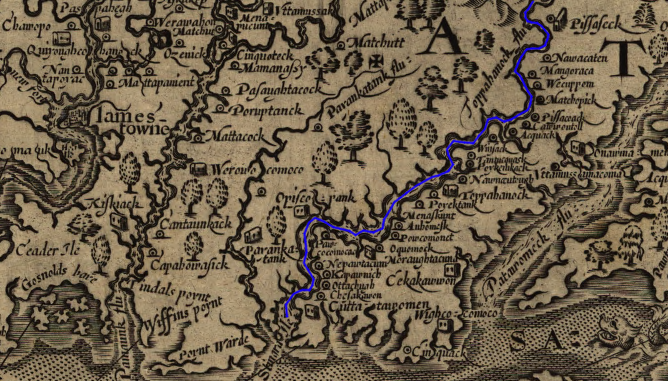

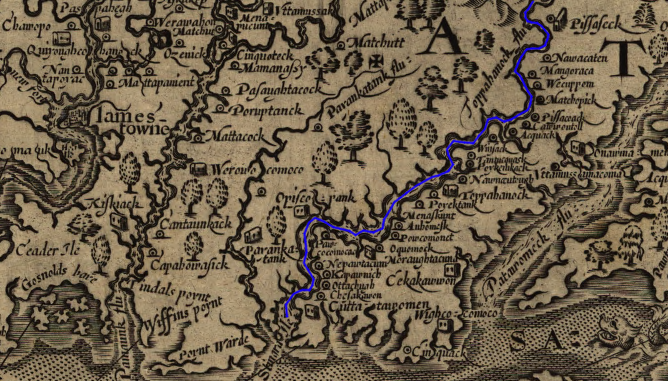

John Smith documented an imbalance of towns on the north vs. south banks of the Rappahannock River (marked with blue line), suggesting an attempt to use the river as a protective barrier against control by Powhatan

(NOTE: North is to the right, not towards the top of the map)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

Evidence is clear that "Indians" were living in Virginia at least 12,000 BCE (Before the Common Era), and perhaps as much as 15-20,000 years ago. There must be far more archeological resources than we have discovered, but four centuries of plowing farmland, and more recently the dramatic urban/suburban development across Virginia, has disturbed almost all of the pre-colonial surface on the land.

The Chesapeake Bay is only several thousand years old, and for 18,000 years a rising ocean has been drowning the ocean shoreline of Virginia. Near the bay, artifacts of the first hunting/gathering camps of the Paleo-Indians and the initial sites of the Archaic Period may be buried under sediments deposited over the last 6,000 or so years. Further offshore, on what is now the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), even older sediments could bury evidence of the first hunting bands to set up camp in what is now Virginia.

The level of the Atlantic Ocean was lower at the end of the Ice Age, with fresh water locked up in the ice sheets of that era. The Virginia shoreline was far to the east, and much of the modern continental shelf was exposed above water.

One day, when underwater archeology is much easier, we may discover a great deal of information about the first Virginians - under the Chesapeake Bay, and as much as 30 miles offshore from Virginia Beach on the Outer Continental Shelf. The Virginia Department of Historic Resources is quite conscious of the potential for underwater archeology east of the Delmarva Peninsula:2

- If humans lived in the region over the past 22,000 years, over 50 percent of the former upland environment available for human occupation and settlement currently lies submerged beneath the Atlantic Ocean and the Chesapeake Bay.

-

underwater research may one day reveal how the first Virginians lived

Source: National Park Service, Archeology Program

The best clues to understanding prehistoric societies, the cultures that existed before European colonists began writing down their perspectives on Native Americans, are the tools used by the hunters/gatherers and the remnants of their camps. Most artifacts are stone, but a few seeds and bones charred by campfires have survived and facilitate dating ancient archeological sites.

Unlike clothing based on animal skins and plant fibers, food, or even bones, the stone tools and chards of pottery in the ground have stayed unchanged over the centuries. Archeologists recognize different time periods by variations in the specialized designs of stone tools and pottery, and the different designs are the best modern indicate to cultural changes. Gradual shifts in designs suggest a group stayed in place as styles evolved, while rapid changes suggest a group of people with a different culture migrated into that place.

Evaluating population changes based on changes in stone tools and pottery requires determination of dates when new technologies were introduced/developed at a location. Top layers of soil are younger than layers deeper down, so an artifact found at depth is typically older than an artifact found on the surface.

Not all items "on top" are younger. Items tossed into human-dug pits can appear to located at an older depth. Bioturbation of soil by burrowing animals, or falling trees bringing a rootball to the surface, can confuse the picture. At the Williamson Paleo-Indian site in Dinwiddie County, archeologists found a piece of chert that had been chipped by Paleo-Indian and buried underneath the accumulated soil, until a crayfish brought it to the surface.3

a crayfish ejected a Clovis age chert artifact from its hole at the Williamson site

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, The Williamson Clovis Site, 44DW1, Dinwiddie County, Virginia (Figure 9.4)

Archeologists are careful to document the different layers of soil when excavating a site. They look for organic materials associated at a common level with tools and pottery. Radiocarbon dates of charcoal from a hearth can be used to determine the age of stone tools found at the same layer, or stratum. Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) can be used to date when certain minerals were last exposed to sunlight on the surface.

It is common for farmers across Virginia to have a collection of "arrowheads" collected after plowing. All arrowheads are "points," but not all points are arrowheads. Human-shaped stone tools used on the tips of spears and other devices for killing animals also are called "points." Other stones were shaped to serve as knives, scrapers, awls (needles), and other purposes.

Bow and arrow technology had not been invented when the first humans walked into Virginia. For over 10,000 years, until the bow and arrow was developed in the Middle Woodland period, stone/bone projectile points were attached to spears and atl-atl shafts in Virginia rather than to arrows.

Palmer/Kirk and other notched points developed in Archaic Period

Source: National Park Service, Terminal Paleoindian Occupations in the Southeast (10,800-10,000 rcbp, ca. 12,900-11,450 B.P.)

Native Americans also shaped antlers, wood, and shells. A small amount of copper was used for jewelry, but Native Americans in Virginia never developed a technology based on metal. They lived within a Stone Age culture until the Europeans arrived.

Once pottery was invented, the designs and styles of bowls and other items provide additional clues to Indian lifestyles before contact with Europeans. (In centuries to come, future archeologists might study the cultural differences between Singapore and Norfolk during the 21st Century by examining the different types of computer chips found in our landfills.)

Intact, undamaged tools from the Paleo-Indian period are rare. Most items made from skins, wood, and bone have disappeared through natural decay of the organic material. Most stone tools have been reworked, with flakes of stone chipped away to repair a tool after damage. Broken stone tools and pottery are discovered by archeologists; intact points and pots are rare, in comparison to items discarded after breakage.

even after development of pottery, turtle shells were used for cups and bones were carved to make fishhooks, needles, and other tools

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Turtle Shell Cup with Bone Tools

A stone knife may be resharpened only so many times to generate a new sharp edge, before the tool is worn out and thrown away because too much rock has been chipped away to permit further use. In addition, there is much stone litter from chipping a tool out of a core or blank of raw stone. Lithic scatters ("debitage") are waste rock, discarded as a point was shaped.

From a naive collector's point of view, broken items are of lesser value than an intact spear point or pot. From an archeologists perspective, however, broken items and even debitage can offer valuable insight into the culture of the time and place. The Clovis points may have been produced only during a short window of time 11,000 years ago that lasted just 200 years, but finding a broken base of a point with the distinctive flute provides valuable information about when a site was occupied.4

Nonetheless, there is an obvious distinction in our appreciation of broken vs. intact artifacts, and a sense of shock when excavation or handling damages items of great age. Virginia archeologists maintain a survey of over 1,000 fluted points, to document the remnants of the Clovis culture in the state. The description of Point #583, which was located near the Meherrin River five miles east of Emporia, notes it was:5

- "...found in 1977 by a farm laborer, dropped and broken into two pieces." And that happened after it had existed unbroken for 10,500 years!

The Native Americans in the Archaic Period saw global warming occur, with major effects on the landscape, as the last Ice Age ended. The earliest Virginians would have seen the valley of the Susquehanna River drown, and watched the Chesapeake Bay form as water levels of the Atlantic Ocean rose. Those early immigrants to what we now call Virginia would have seen the spruce-fir forests retreat to the north, as Virginia's environment shifted towards an oak-hickory-pine forest.

mud protected the edge of a canoe as fire was used to carve out the center

The number of Native Americans in Virginia has grown from the original "first Virginian" who migrated into the state long ago. Today, there are 200 people/square mile in the entire state of Virginia, and even Highland County had over 5 people/square mile. When Jamestown was founded, population density on the Coastal Plain was only 2 people/square mile, but that was up significantly from the population in the state at the start of the Archaic Period:6

- Late Paleo-Indian Period (initial settlement - 8000 BC) - 725 to 1,450 people in all of Virginia

- Early Archaic Period (8000 BC to 5000 BC) - slightly over 1,000 to slightly over 3,000 persons living on Coastal Plain

- Middle Archaic Period (5000 BC to 3000 BC) - slightly over 3,000 to about 5,000 persons living on Coastal Plain

- Late Archaic Period (3000 BC to 1000 BC) - about 5,000 to about 8,000 persons living on Coastal Plain

- Woodland Period (1000 BC to 1600 AD) - about 8,000 to about 13,000 persons living on Coastal Plain

The "periods" are artificial boundaries established by archeologists to describe major changes in culture. Between the periods, the technologies change - as do, presumably, the organizational characteristics of Native American societies. The dates for each period are rough boundaries.

Within a period, people living in different places were culturally diverse as new ideas, new tools, and new environmental conditions caused new patterns of behavior. There is no such thing as a "standard" person living in any particular period.

By 900 AD, the Native Americans in the Woodland Period had adopted agriculture and were growing corn. In the Coastal Plain, villages moved to floodplains where soils were richer. On the Eastern Shore, however, fish and shellfish were readily available, and corn farming appears to have been less significant there. Since 3000 BCE in the Archaic Period, people living on the Atlantic Coast had repeatedly occupied shoreline sites and tossed shells into waste piles that formed shell rings. Some settlements were occupied for over 1,000 years, so a pattern of steady occupation of one location does not define a simple time distinction between the Archaic and Woodland periods.7

Population pressures, or simply a desire for greater power, were large enough to generate conflicts over territory. Some Europeans such as Jean Jacques Rousseau viewed the American Indians as noble savages, but the original residents of what is now Virginia were not all conscientious objectors. At times, large sections of the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley may have been used only for hunting and as a buffer zone between groups, with few permanent villages.

Perhaps the surplus of food after adoption of corn triggered disputes over control of the storehouses and distribution of the supply. Long before the English settled at Jamestown in 1607, different groups restricted access to land and water by their rivals.

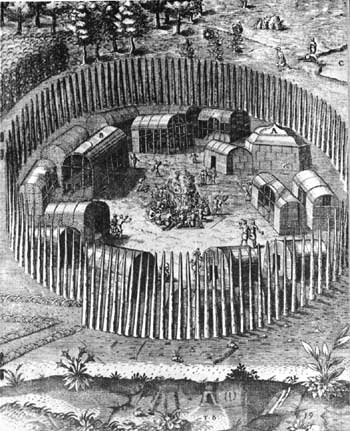

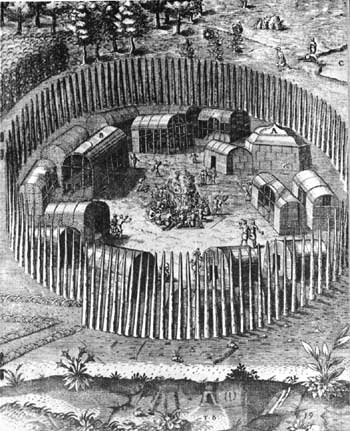

The original Virginians did not live in peace and harmony where everyone just "got along" with everyone else, until the Europeans brought discord to America. European settlers arriving in the 1500's discovered that Native American towns were protected by wooden walls, which would have required back-breaking labor to construct when the only tools were made of stone, bone and shell.

Theodore DeBry's engravings of fortified village of Pomeiooc near the Roanoke Colony, 1587

Source: National Park Service, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

how a Native American palisade may have looked, if poles were placed close together without woven vines/branches

(reconstructed at Henricus Historical Park in Chesterfield County)

In 1607, John Smith discovered that the Algonquian-speaking tribes under Powhatan's control blocked access to the protein-rich estuaries of the Chesapeake Bay from Siouan-speaking tribes further inland. The Siouan-speaking Manahoac and Monacan tribes west of the Fall Line could not collect shellfish from Tidewater Virginia, controlled by Powhatan's Algonquian-speaking tribes.

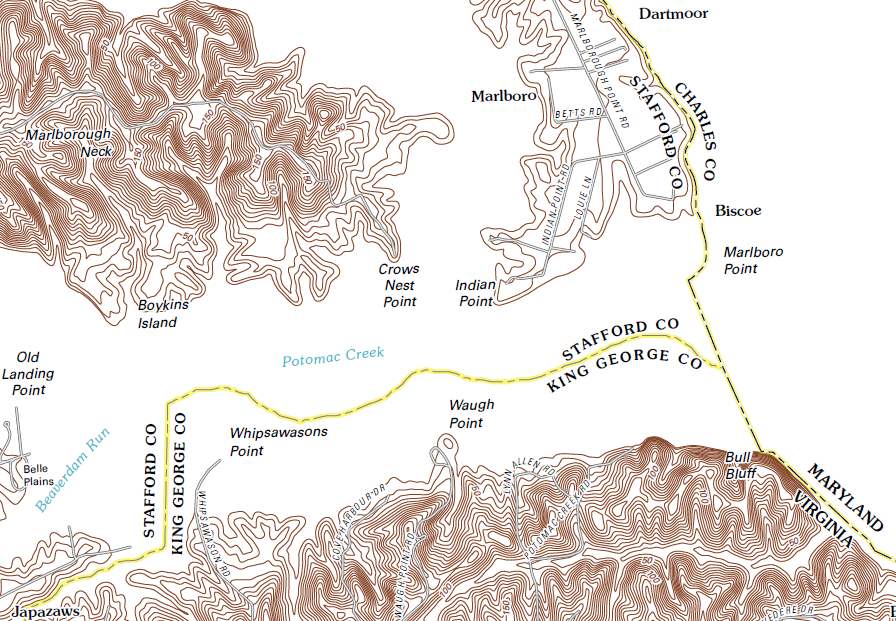

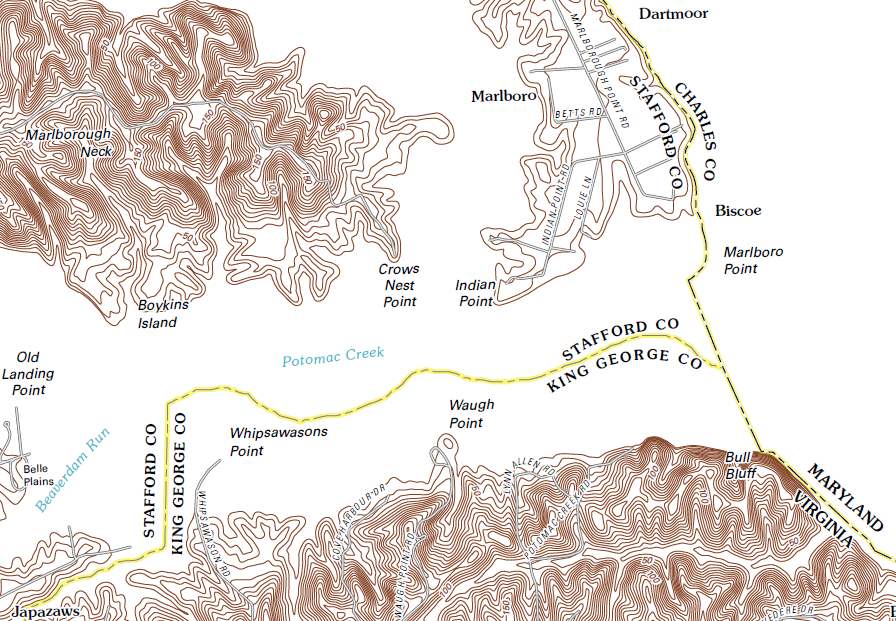

Indian Point, named after Patawomeck village where Pocahontas was captured in 1613

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Passapatanzy 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2011)

Controlling food resources did not come without a fight. The Algonquian-speaking Patawomeck tribe built a log palisade to enclose their town at the mouth of Potomac Creek. The palisade may have been for protection from the Algonquian-speaking tribes under Powhatan (to the south) and the Piscataways (to the north), as much as from the Siouan-speaking Manahoacs (to the west).

Such fortifications were not unique to Tidewater. A similar barricade was also built by those who lived along Wolf Creek in Southwestern Virginia, in a village of about 100 people that was occupied for about 5 years around 1500 AD. Over 200 saplings 3-4" thick were placed in 15" deep holes, creating a 10' tall barrier surrounding a village with 11 houses. The saplings were spaced one foot apart, so vines and branches may have been woven between the posts to block entry:8

- This would have made the palisade look like a wicker basket, but it would have stopped an arrow. It would also have prevented the undetected entry of an enemy seeking to penetrate the village to attack sleeping inhabitants...

-

- The irregularity of the palisade indicates the work was done piece-meal by various people building only to general guidelines and not to a marked-out circle on the ground. It is probable that each family was assigned the section of wall next to the family house as a project... One family wanting more work-space adjacent to the house might bow the palisade a few feet out from the house, and another seeking short-cuts might flatten the palisade line closer to the house.

reconstructed palisade at Wolf Creek, with woven vines/branches between poles

(Bland County)

location of Wolf Creek archeological site in 1895, long before I-77 was built

Source: US Geological Survey, Pocahontas 30X30 topographic quad (1895)

Links

References

1. Virginia Council on Indians, A Guide to Writing about Virginia Indians and Virginia Indian History, September 19, 2006

(last updated June 2010), http://indians.vipnet.org/resources/writersGuide.pdf (last checked June 22, 2012)

2. Darrin Lowery, "The Challenge of Conducting Prehistoric Underwater Archaeology," Notes on Virginia 2009-2010, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Number 53 (2009-2010), p.50, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/Notes_No.53.2009_sm.pdf (last checked June 22, 2012)

3. "The Williamson Clovis Site, 44DW1, Dinwiddie County, Virginia: An Analysis of Research Potential in Threatened Areas," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 2003, p.152, http://dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/Archeo_Reports/DW-087_44DW001_Williamson_Clovis_Site_2003_VDHR_report.pdf (last checked August 8, 2017

4. Michael R. Waters, Thomas W. Stafford Jr., "Redefining the Age of Clovis: Implications for the Peopling of the Americas," science, Vol. 315 no. 5815 (February 2007), p.1122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1137166 (last checked July 3, 2012)

5. Ben McCary, "Survey of Virginia Fluted Points, Nos. 537-603," Quarterly Bulletin, Archeological Society of Virginia, Vol. 34 No. 3 (March 1980), p.175

6. E. Randolph Turner III,, "PaleoIndian Settlement Patterns and Population Distribution in Virginia," in Paleoindian Research in Virginia: A Synthesis, J. Mark Wittkofski, Theodore R. Reinhart (ed.), Special Publication No. 19 of the Archeological Society of Virginia, 1989, p.86; E. Randolph Turner III, "Population Distribution In The Virginia Coastal Plain, 8000 B.C. To A.D. 1600," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 6 (Summer 1978), p.67, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914168; "Population, Census, April 1, 2010," QuickFacts, Bureau of Census, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/VA/POP010210#viewtop (last checked August 8, 2017)

7. R. Michael Stewart, "The Status Of Woodland Prehistory In The Middle Atlantic Region," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 23 (Fall 1995), p.193, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914397; Victor D. Thompson, C. Fred T. Andrus, Rachel Cajigas, Anna Semon, Matthew C. Sanger, Howland, Clark Alexander, Elliot H. Blair, Isabelle Lulewicz, Karen Y. Smith, Carey J. Garland, Carla S. Hadden, David Hurst Thomas, "Shellfishing, sea levels, and the earliest Native American villages (5000–3800 yrs. BP) of the South Atlantic Coast of the U.S," Scientific Reports, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72567-w (last checked November 6, 2025)

8. Howard MacCord, Sr., "Wolf Creek Indian Village," reprint of "The Brown Johnston Site: Bland County, Virginia" from the Archeology Society of Virginia June 1971 Quarterly Bulletin, p.8

"Indians" of Virginia - The Real First Families of Virginia

Virginia Places