Bear Mountain and St. Paul's Mission (next to cemetery), focal points of Monacan culture today

(Amherst County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tobacco Row Mountain 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2010)

Bear Mountain and St. Paul's Mission (next to cemetery), focal points of Monacan culture today

(Amherst County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tobacco Row Mountain 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2010)

Between November 1999-March 2020, the Monacan Tribe re-created and interpretive a palisaded town at Natural Bridge. This was done in partnership with the commercial owners of the tourist site, who were trying to offer more attractions.

For the tribe, the site offered an excellent opportunity to educate far more people about Monacan culture and heritage, beyond the small number of people who visit the Monacan Ancestral Museum in the Blue Ridge. When Natural Bridge became a state park in 2016, the re-created village was retained for both education and as a tourist attraction.

As advertised by the Virginia Tourism Corporation, the Natural Bridge exhibit was the only re-created Monacan town:1

The building materials and construction techniques in the village reflected the technology and culture of the 1700's, except the reeds were not the local cane that would have been used 300 years ago. That cane is now rare, due to overgrazing.

At Natural Bridge the Monacan use cattail reeds, a species which would have grown naturally in their region's swamps 400 years ago. It took two years to collect 5,000 cattail leaves to cover one shelter at the village. The phragmites reeds used in some Indian village recreations is a non-native invasive species, one that is overwhelming natural vegetation in the marshes of Tidewater Virginia. 2

The site of the interpretive exhibit in the valley of Cedar Creek at Natural Bridge was chosen because there was an audience there. No Native American group actually built a town at that location. By the time settlements were established in the Woodland Period, towns were located where agricultural land was available. Defending a town in the narrow valley, where enemies could easily fire arrows and throw rocks from above, would have been too difficult. That location offered a chance to engage with tourists in modern times, but no opportunity for escape in historic times.

The Monacans took advantage of archeological studies and researched carefully how to construct a town that reflected life in the 1500's and 1600's. The number of dwellings, the distance between structures, the size of the garden, and even the garbage midden were constrained by the narrow valley floor and other infrastructure at the tourist attraction.

At the modern Natural Bridge tourist attraction, visitors saw people dressed in deerskins but with enough covering of the skin to match modern moral standards. The interpretive site was created to be practical as will as informative - visitors did not see a re-creation of how people extracted sinews from a deer carcass, or experience the flies and other insects that must have been associated with the human settlements.

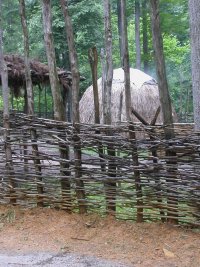

The palisade of sticks and woven branches surrounding the town reflected major investment in security infrastructure. Saplings were cut down and the bottom of the poles hardened in fires, then placed in a ditch and connected together with branches. The mud daub on the bottom helped exclude wildlife from wandering into the town. A ditch surrounding the outside the wall was the source for the mud.

The palisade was designed to deter attackers from racing directly into the village. Modern reenactors and others debate whether a wall around the village would have included the horizontal branches woven to make a tight barricade.

Monacan palisade and "ati" (house)

Village walls may have been just a loose fence of vertical logs with no horizontal branches, slowing an attack but allowing residents to escape by slipping through the gaps. Archeological evidence does not tell us; the postholes preserved in the soil do not document the design of the wall above the posts.

reconstruction of Native American palisade (protective barrier) at Monacan village in Natural Bridge

Natural Bridge must have been a special place to Native Americans ever since Paleo-Indians discovered the unique geological feature as much as 15,000-20,000 years ago. A visitor does not do not need modern technology or cultural sensitivities to recognize that the bridge of stone is a special place.

About 100,000 people per year saw a recreation of structures that were historically illuminating and stimulate thinking. If the re-created village had been located in 1999 at the confluence of the Rivanna and James rivers, the historical site of Rassawek, visitation and public education would have been minimal.3

when enough conflict justified constructing wooden barriers with stone and bone tools, a village in the valley would have been extremely vulnerable to attack

The exhibit closed during the COVID-19 epidemic in March 2020. It slowly decayed in the following years, though the palisade remained mostly intact. By 2025, archeology students at James Madison University had cleared the fallen material and excavated the site as an experiment. They discovered that after just a short period of abandonment, many of the features (such as the postholes) resembled what was discovered at Woodland Period digs across the region.4

European mapmakers repeated the information acquired by early Jamestown colonists about four Monacan towns west of the Fall Line

Source: University of North Carolina, Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Virginiae partis australis et Floridae partis orientalis interjacentiumq[ue] regionum nova descriptio (c.1640)