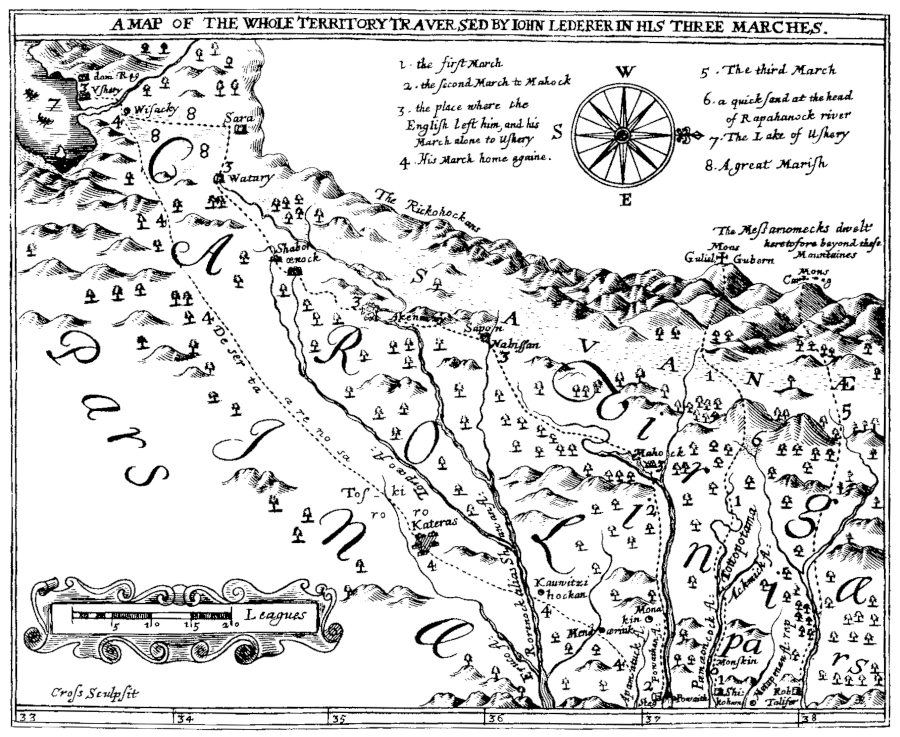

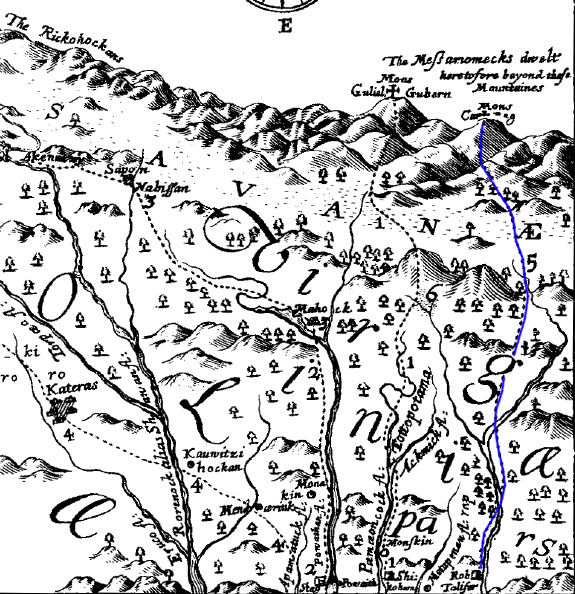

map of Lederer's journeys, based on his claims

Source: University of North Carolina, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

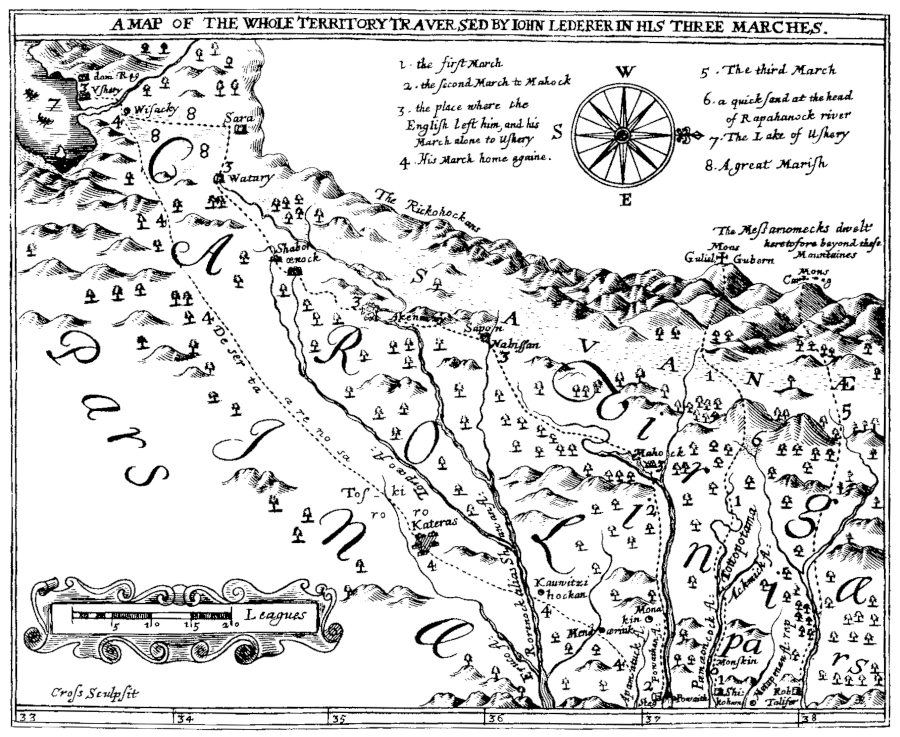

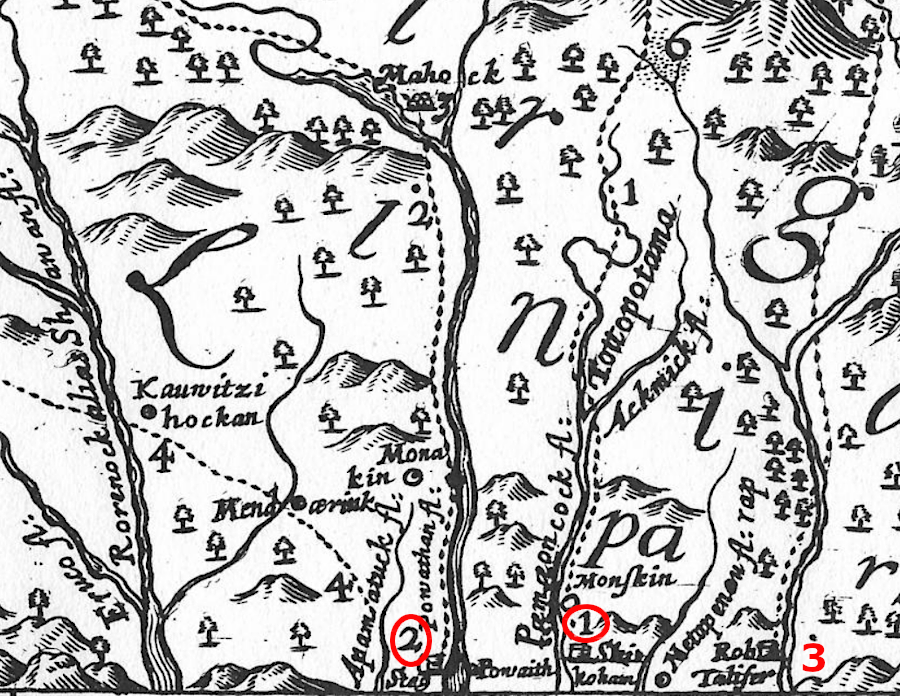

map of Lederer's journeys, based on his claims

Source: University of North Carolina, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

The first European to reach the top of the Blue Ridge was not English but a German physician, John Lederer. He went on three expeditions to the Blue Ridge between 1669-1670. He had received a commission from Governor William Berkeley. The governor was interested in expanding the fur trade in Virginia, which offered him the potential for substantial personal profit.

Others also sought connections with western tribes that could provide a reliable supply of deerskins. In 1671, a year after Lederer's expeditions, Abraham Wood sent Thomas Batts and Robert Fallam for Fort Henry (Petersburg) to the west. They reached the New River, becoming the first Virginia colonists known to have crossed the Eastern Continental Divide. In 1673, James Needham and Gabriell Arthur left Fort Henry to establish trading connections with the Cherokee. They followed the route used by Lederer on his second journey to Sapony, Akenatzy on the Roanoke River (which they called Hanathaskie), and Sara in North Carolina.

Lederer wrote an account of his journeys in Latin. His journals were translated into English by William Talbot, Proprietary Secretary of Maryland. Those journals demonstrate that by 1670 he had identified the major landforms and physiography of Virginia, while searching for the Northwest Passage offering a water route to the Pacific Ocean and trading relationships with Native American tribes.

Lederer's discoveries were not honored by the English in Tidewater Virginia, and later historians have questioned if his journals were based on actual travels. His translator noted that Governor William Berkeley had authorized Lederer's travels, but that "our Traveller at his return, instead of Welcome and Applause, met nothing but Affronts and Reproaches."1

Lederer's traveling companion on his second trip, Major Harris, returned early while Lederer himself continued further west. Harris apparently disparaged the German in order to increase his own reputation as an adventurer in Virginia. Harris may have assumed that Lederer would never return alive to contradict him.

Lederer's translator attributed this rejection to jealousy and embarrassment that a non-Englishman had been brave enough to explore the unknown. In addition to personal jealousy, the Tidewater landowners recognized that increasing the supply of tobacco-growing land west of the Fall Line would inevitably attract settlers. This would make it harder to obtain the labor needed for growing tobacco on existing lands in Tidewater. The enthusiasm for western exploration may have been limited by the Tidewater planters' recognition that western settlement would create competition.

The First Journey, March 1669

On his first exploration, Lederer followed the Pamunkey River upstream from "Pemaeoncock Falls" to the Southwest Mountains near modern-day Orange/Gordonsville.

It is difficult to match the place names and trip descriptions in his journal with modern maps. It is not immediately clear what falls on the Pamunkey River could be Pemaeoncock Falls.

Lederer's first recorded journey started on March 9, 1669. He started with three Native American guides at a town named Shickehamany, apparently located on the north bank of the Pamunkey River. However, if you pronounce the word rather than emphasize the spelling, it could be "Chickahominy." Members of that tribe had been forced from their original homeland on the Chickahominy River. They were pushed north to the lands between the headwaters of the York and Rappahannock Rivers, not yet settled by English colonists.

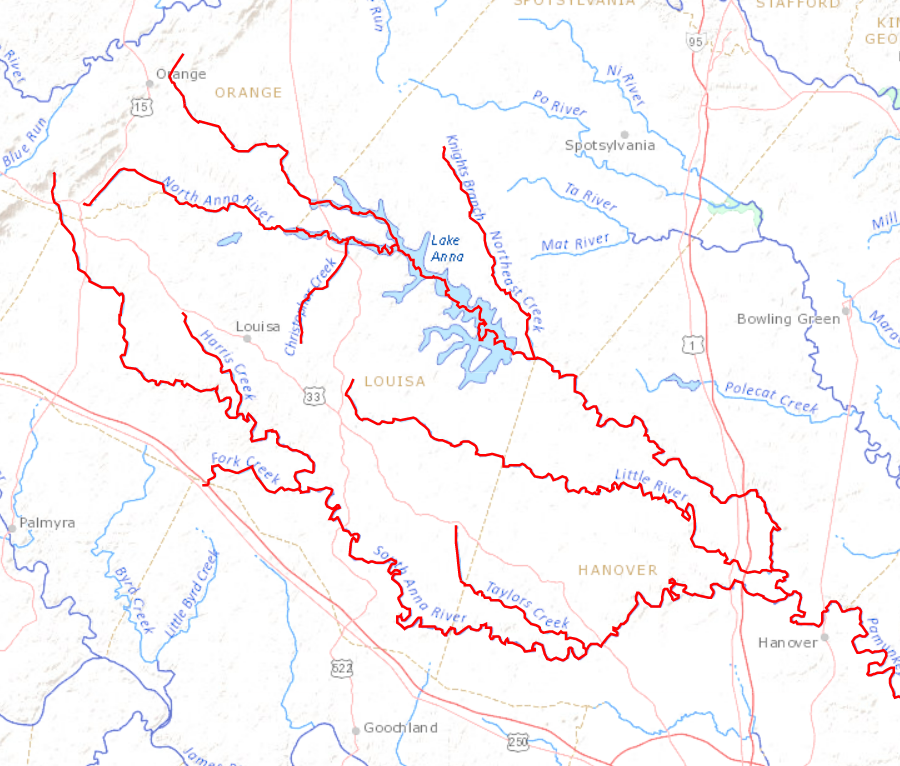

Lederer ran into marshy ground between the Pemaeoncock (Pamunkey) and Matapeneugh (Mattaponi) rivers. He crossed to the south bank of the Pamunkey "where its North and South-branch (called Ackmick) joyn in one." The Native Americans did not name places after English queens, but the Acmick is known today as the North Anna River.2

Lederer may have identified the junction of the two branches forming the Pamunkey at a location further downstream than our modern definition. He said one stream in the peninsula formed by the two branches was named after Tottopottoma, who had died in battle while assisting the English settlers. The battle was in 1653 at Bloody Run on Church Hill in Richmond, when the Algonquian-speaking Powhatans had allied with the English to prevent "western" Indians from starting at settlement at the falls of the James.

Modern Tottopottomy Creek joins with the Pamunkey River just west of where modern-day US Route 360 crosses the river in Hanover County, a dozen miles away from the modern junction of the North and South Anna.

Lederer's reference to marshy ground forcing him to detour is another piece of evidence that the initial definition of the two branches was downstream from the current definition of the start of the Pamunkey River. The current junction of the North and South Anna is not mapped as "marshy," but downstream of Moncuin Creek the Pamunkey River is lined with marshes. The bottomlands on the Pamunkey River have been cleared for farming purposes, but were once marshes far harder to navigate about 330 years ago.

He apparently traveled with his horse and guide up the North Anna River. On March 13, he reached what he called the "first Spring" (headwaters) of the Pamunkey River, which would be around the modern town of Orange.

Lederer's options for following the Pamunkey River west from Pemaeoncock Falls

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

On March 14 he spotted the first sign of mountains to the west:3

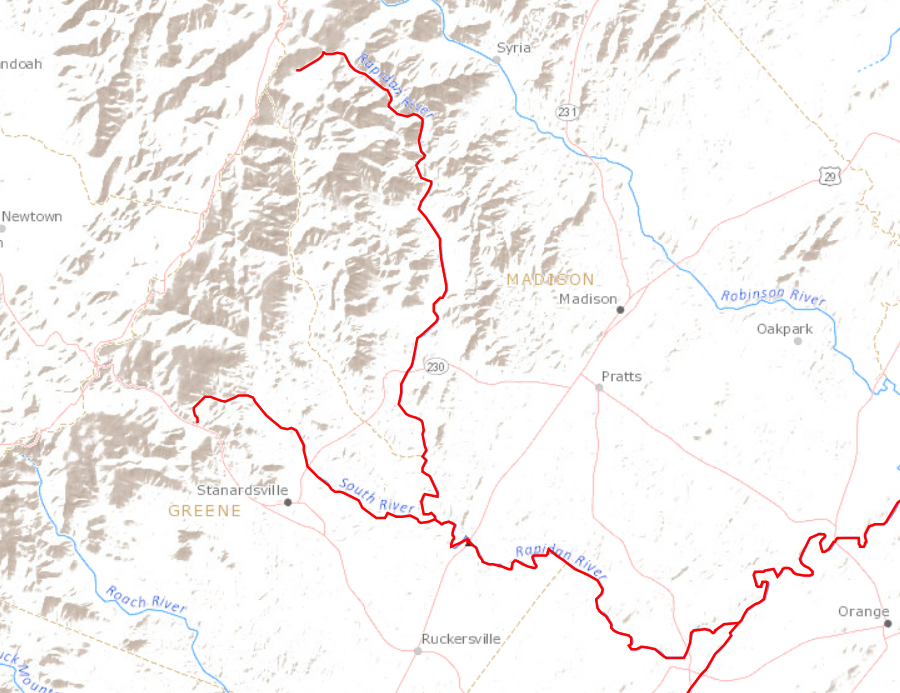

Lederer's first journey (red line) took him up the North Anna River

Source: University of North Carolina, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

The modern traveler driving west on Route 17 from Fredericksburg may have a similar experience near Morrisville. Looking west from Mountain View on Route 627 in Stafford County can be equally deceiving.

Lederer reported seeing snow on the mountains. He did not mention seeing flowering plants in early March, but evidently there was enough growing for grazing his horse. Assuming that the water level was low before the spring runoff, he may have been at approximately the location of modern Lake Anna. It is possible that he did not view the Blue Ridge clearly until reaching modern-day Gordonsville.

He reports that he crossed the "South-branch" of the Rappahannock River, presumably what we now call the Rapidan, and reached the mountains on March 17 after traveling for eight days.

possible routes, if Lederer followed the Rapidan River to the Blue Ridge

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

Lederer climbed the Blue Ridge on March 18. His effort to ride upward on his horse, used primarily to carry supplies, was a failure. He left his one remaining Indian guide at the bottom with the horse.

He claimed he saw the Atlantic Ocean to the east. The Chesapeake Bay was 100 miles east, and the ocean nearly double that; Lederer saw just low clouds on the horizon. His report of higher mountains to the north and west is more credible.

If he had followed the Rapidan River to its headwaters, he would have reached the top of the Blue Ridge south of the current Big Meadows Visitor Center in Shenandoah National Park, perhaps near Hazeltop Mountain. He would have been looking west across Powell, Grindstone, Smith, and Dovel mountains. He may have seen Massanutten Mountain, and perhaps even North Mountain on the western edge of the Shenandoah Valley.

He turned back east on March 24, 1669. If his dates are correct, he had wandered on the Blue Ridge in the snow for four days looking for a pass through the mountains. That would require that Lederer had somehow carried enough provisions up the mountain to survive multiple nights on a barren snow-covered mountaintop at the end of winter, but lacked the skill to find a route on the west side of the Blue Ridge down to the Page Valley.

He may have been deterred by concerns that the Massawomacks living west of the Blue Ridge might not welcome a visitor, at least when food supplies would have been low.

red X marks where Lederer may have looked west from the Blue Ridge on his first journey, if he traveled up the Rapidan River and then the Conway River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lederer's first route did not blaze a trail to the west. No major highway today runs from the confluence of the North Anna and the South Anna rivers to where he climbed the Blue Ridge. Route 33, the "Mountain Road" from Richmond, stays close to the watershed divide rather than follow the Rapidan River before passing through Swift Run Gap.

Lederer thus shares one characteristic with Lewis and Clark; his initial route was not the best. The first crossing by Lewis and Clark over the Rocky Mountains is at Lemhi Pass near modern-day Missoula, Montana. The preferred crossing today is where I-80 goes through South Pass in Wyoming. The first Surveyor landing site on the moon, or the first Viking landing site on Mars, may not evolve into a future transportation destination either.

The territory through which Lederer passed in 1669 appears to have been unsettled; he does not mention seeing any Native American towns. He describes the Piedmont as a wilderness:4

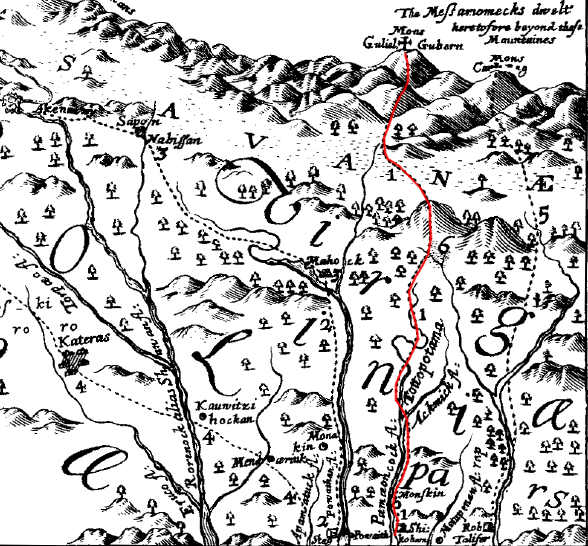

The Second Journey, May 1670

On his second journey, John Lederer traveled initially with a Major Harris. He led a party of 20 English explorers, plus five Native Americans. The expedition left from the Fall Line on the James River.

The start of the trip showed Lederer's willingness to listen to the Native Americans in contrast to Major Harris. The two travelers asked a Monacan how to reach the mountains, and he drew two paths in the dirt using a stick. One path may have followed the James River valley, and the other path may have followed the Appomattox River valley. Major Harris insisted on using his modern compass in order to go due west. That route, perhaps tracing the watershed divide, led them over "steep and craggy cliffs" that could have been bypassed had the European men followed directions of an experienced local traveler.

After two weeks of travel from May 20-June 3, 1670, the party reached the "south branch" of the James River at a place called Mahock. Lederer may have defined the "north branch" to have been where the Rivanna joins the James at modern-day Columbia (the junction of Fluvanna, Goochland, and Cumberland counties) or where the Rockfish River joins at Howardsville (the junction of Albemarle, Nelson, and Buckingham counties).

Lederer wrote that Major Harris had become excited at seeing the south branch veer to the north. The nearby hills were impassably steep, but the river was still as broad as at Manakin.5

Based on those clues, they may have traveled far enough west to reach the major shift in the James River's direction near modern-day Lynchburg.

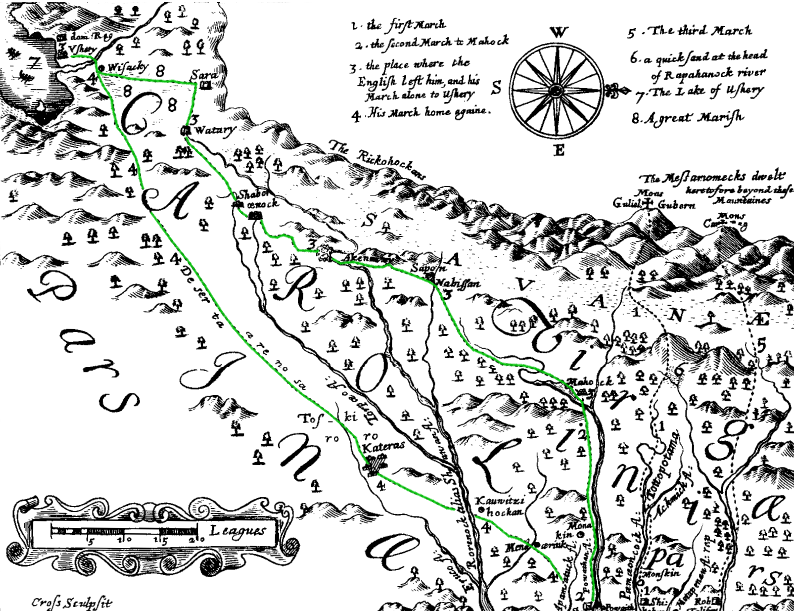

Lederer's second journey (green line) took him southwest through the Piedmont to the base of the Blue Ridge

Source: University of North Carolina, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

Lederer was happy to part from Major Harris and his retinue of English colonists and Native Americans on June 5. He continued with just one Susquehannock guide, turning south and southwest to avoid the difficulty of going uphill. His commission from Governor William Berkeley included direction to discover "a passage to the further side of the Mountains," not to climb the mountains.

He thought he was 100 miles from Manakin when, after four days of travel, he reached the Nahyssan town of "Sapon" on the Roanoke River on June 9th. Lederer calculated that Sapon was in Carolina, south of the Virginia border. He may have been in Bedford County near the Peaks of Otter.

The Native Americans at Sapony spoke a Siouan language similar to that of the Tutelo and the Monacans. The Occaneechi spoke Siouan at their trading island in the Roanoke River, but as traders they could communicate in various languages.

Lederer recognized the people at Sapony as potentially hostile; they had been at war with the "Christians" for the last decade. He successfully bargained glass and metal for hospitality and exchanged information with them, describing his travels and learning. Lederer must have been a good diplomat and storyteller; he was invited to marry into the tribe.

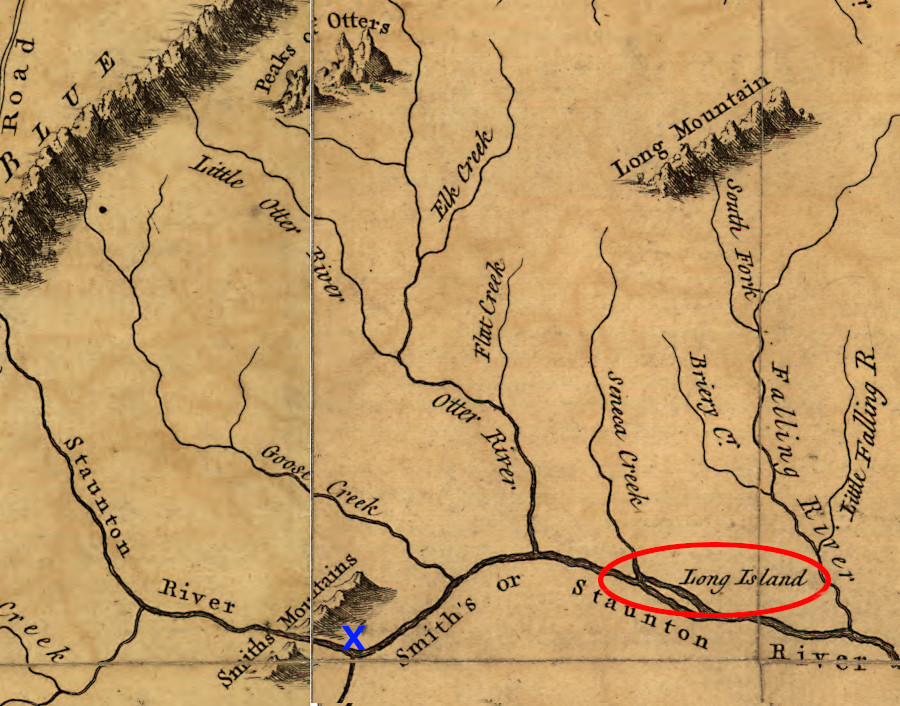

On June 12, 1670, the two explorers reached the town of Akenatzy on the Roanoke River. Lederer estimated that he had traveled 50 miles from Sapony. Akenatzy may have been located on what Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson labelled "Long Island" on the map they produced 85 years later. It became the center of the Ocaneechi trading route transporting furs to the colonists at Petersburg.

Akenatzy could have been at Long Island (red circle) or even near Smith Mountain Gap (blue X)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Akenatzy could have been at Long Island (red circle) or even near Smith Mountain Gap (blue X)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

An alternative possibility is that Akenatzy was upstream of modern-day Altavista. The town could have been on a peninsula rather than on an island, jutting into the Roanoke River near modern Smith Mountain Lake or Leesville Lake. Lederer does not mention the distinctive gap in the mountains through which the Roanoke River flowed, but does describe the town as "being naturally fortified with Fastnesses of Mountains, and Water of every side.6

Lederer saw four "stranger-Indians" there, and speculated they had traveled from California to Akenatzy. Their bodies were decorated with a yellow paint created from a form of arsenic sulfide which he called Auripigmentum, using the Latin term for a pigment known since Roman times.

The stranger-Indians were apparently welcome, but Lederer witnessed the assassination of a Rickahocan emissary visiting the Akenatzy along with five companions. Lederer was invited to a party in the evening:7

Lederer traveled from the falls of the James River to Akenatzy, perhaps 150-200 miles, between May 20-June 12, 1670 (NOTE: North is to the right)

Source: University of North Carolina, A new discription of Carolina by the order of the Lords Proprietors (by John Ogilby, c.1671)

Lederer and his Susquehannock guide "slunk away" on June 14. They went 30 miles further south-southwest and reached the town of the Oenock (Eno) two days later. That site may be near modern-day Eden, North Carolina. He described the society there as democratic, with advice from elders highly respected.

They continued to travel south and southwest along the east slope of the mountains, visiting different towns and trying to discover what lay on the other side to the west of the mountains. Fourteen miles west-southwest, he met "Shackory-Indians." Though it is tempting to consider Shakory to be equivalent to Cherokee, Lederer moved on quickly because they were so similar to the Siouan-speaking Eno in their customs and manners. The Shakory decorated themselves with what Lederer called antimony, which may in fact have been flakes of the mica common in the Blue Ridge of North Carolina.

Lederer and his guide traveled another 40 miles to Watary, where the culture was dramatically different. Lederer claimed the king there governed his people as slaves.

When he reached the town of Sara on June 21, he was still on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge and about 10 miles southeast of modern Mount Airy, NC. He noted that there was a passage through the Blue Ridge there, but he was still over 100 miles east of the west-flowing French Broad River.

He reported the Native Americans at Sara used cinnabar (mercury sulfide) to provide purple decoration on their bodies, and also had "hard cakes of white Salt." That suggests he was within trading distance of Saltville.8

Lederer left Akenatzy on June 14 and reached Sara on June 21, 1670

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

On June 25 he reached Wisacky (perhaps modern Waxhaw, NC). His journal indicates he crossed bogs and marshes "over-grown with Reeds, from whose roots sprung knotty stumps as hard and sharp as Flint." The landscape today at the foot of the Blue Ridge lacks the cane breaks that he may have traversed.

On June 26 he reached the town of Ushery, on the shoreline of a lake of the same name. Reportedly the tribe there feared the Oustack-Indians on the other side of the lake, whose women were warriors similar to the men. The residents may have been creating tall tales for the stranger who had arrived uninvited, and one in particular caught his attention. He was told the Oustack-Indians had hatchets made of silver, equivalent to the shiny pommel on Lederer's sword handle.

It is challenging to suggest where the Ushery lake may have been located. Lederer may have been on a wide spot of the Catawba River north of modern-day Charlotte, or on the Yadkin River south of modern-day Winston-Salem. He claims the lake water was brackish, but speculated the taste was from local minerals because he was so far from the Atlantic or Pacific oceans.

While at Ushery, he was told that "bearded men" lived to the south and could bev reached by a two and a half-day journey. He assumed these were Spaniards in Florida, and was unwilling to travel further for fear of being taken captive by them. Further west was "a Government inhospitable to strangers; and to the North, over the Suala-mountains, lay the Rickohockans."

So on June 28, after five weeks of exploration, Lederer started back home.

It took him two weeks to reach the capital of the Tuscaroras at "Katearas." Finding them a threatening tribe, he quickly moved, crossing the "Rorenoke," "Menchoerinck" (Meherrin), and "Natoway" rivers before reaching "Apamatuck" (modern Petersburg) on July 18th after a journey of two months.9

The Third Journey, August 1670

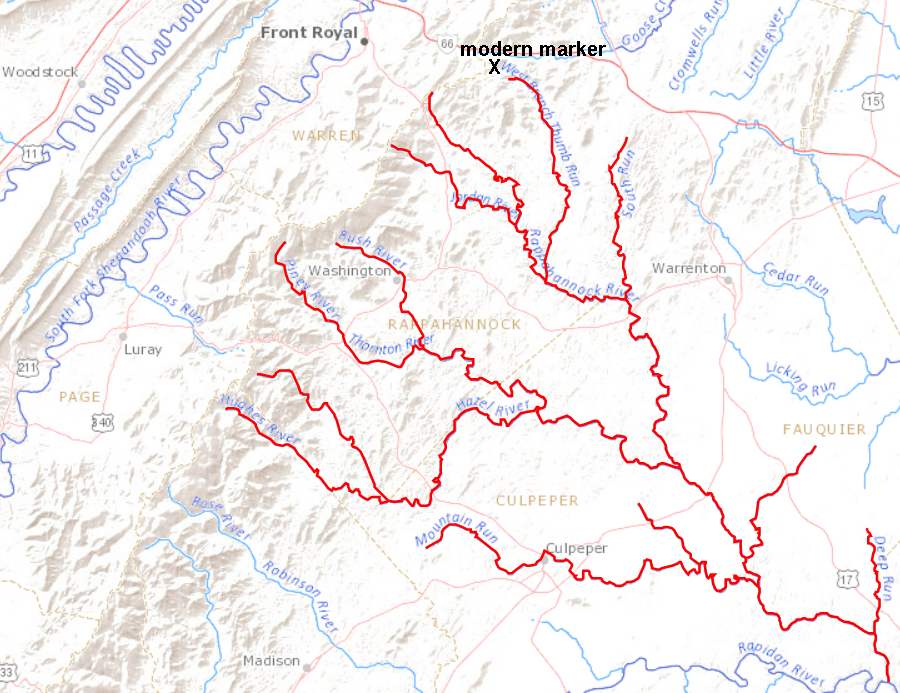

Lederer let no moss grow underneath his feet. A month after returning from his second journey, he walked upstream through the Rappahannock River valley to the crest of the Blue Ridge. He may have been seeking the water level crossing of the Blue Ridge at Zynodoa (Shenandoah). He missed the gap at Harpers Ferry because he stayed within the watershed of the Rappahannock River.

The expedition included Col. Catlet and five Native Americans. The party left from Robert Talliaferro's home on August 20, 1670. Lederer spelled it "Talifer," reflecting the pronunciation of the family name.10

It took a day for Lederer, Col. Catlet, and the five Indians to reach the falls at modern-day Fredericksburg. Travel required another day to reach the junction of the north branch (Rappahannock River) and the south branch (Rapidan River). It is not clear from his journal which branch they followed upstream, but Lederer had already explored up the south branch on his first journey in March, 1670.

Lederer's options for reaching the Blue Ridge by following the Rappahannock River, if he did not choose the Rapidan

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

By August 23, they were far enough upstream that the river was only deep enough to wet the hooves of their horses. By August 26 they had reached the mountains and were no longer able to ride horses. That day they climbed to the top and "drank the Kings Health in Brandy." They named the peak Mons Car Reg, or King Charles Mountain, in honor of King Charles II.

Lederer complained of the cold weather, though he was climbing to the crest of the Blue Ridge at the end of August and had previously been on top in March when there was snow on he ground. From the crest, the explorers saw an even taller ridge that Col. Catlet estimated to be 150 miles away.

There is a monument to Lederer on Route 55 near Linden. He and Col. Catlet could have reached that point if they had taken the northern branch (today's Rappahannock River) rather than the southern branch (today's Rapidan River), and then followed Thumb Run into what is now Fauquier County. Another possibility is that they continued upstream on the Rappahannock River rather than Thumb Branch and reached the crest at Chester Gap.11

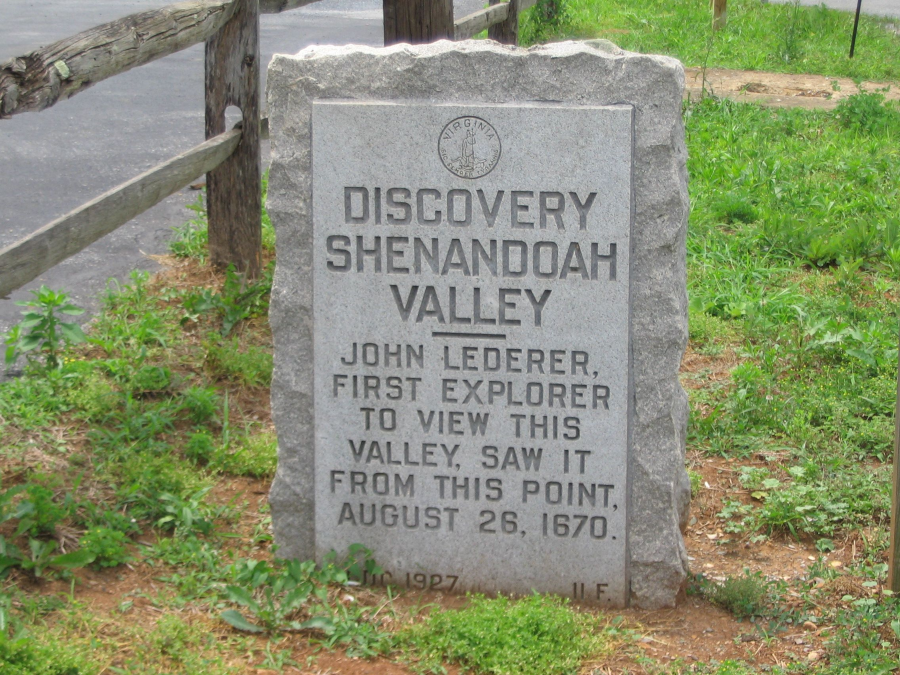

a marker at the headwaters of the West Branch of Thumb Run identifies one possible location where Lederer reached the crest of the Blue Ridge on his third journey in August, 1670

Source: Historical Marker Data Base, Discovery Shenandoah Valley (by Craig Swain)

Lederer, Catlet, and their Native American companions started back home the next day, in part because Lederer had been stung by a spider and his arm had become inflamed. One of the Native Americans made a "plaister" using the snakeroot plant, and also sucked the wound to remove the poison.

Lederer's third journey (blue line) took him up the Rappahannock River to the Blue Ridge, though the highway marker on Route 55 may be placed farther north than his route

Source: University of North Carolina, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

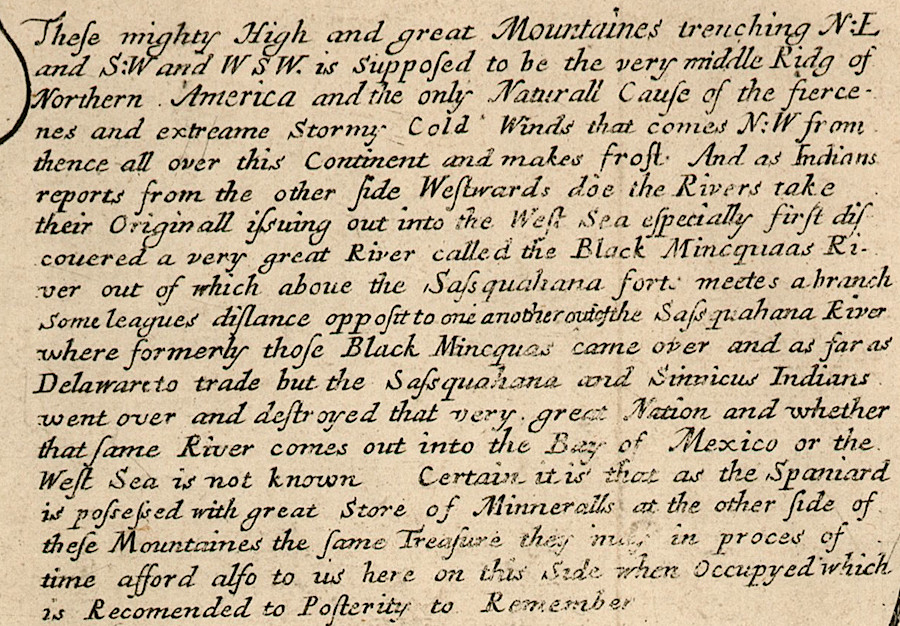

In his "Conjectures of the Land beyond the Apalataen Mountains," Lederer concluded:12

He speculated that an arm of the Gulf of California stretched inland to the west side of the Appalachians. He also guessed that the North American mountains would be similar to the Andes in South America, with long rivers stretching to the eastward but short streams falling quickly into the ocean on the west side. With surprising (but incorrect) insight, he thought the migration of the waterfowl from across the mountains to the rivers running into the Atlantic Ocean indicated that there were no equivalent rivers on the western slope.

Lederer may have manufactured some of the information he recorded, particularly the claim that he found a large inland lake. He was careful to note that of the reported two gaps through the Blue Ridge, he had visited only one in person:13

Lederer left Virginia in 1671. He may have been discouraged by negative rumors circulated by Col. Harris, who had turned back quickly with other English explorers during the second journey. Harris expected Lederer to die in the wilderness rather than to return with valuable information after a successful journey almost to the territory controlled by the Spanish. Lederer moved to Maryland, where Governor Calvert provided him protection. He also issued Lederer a license to trade with the Native Americans in the area explored in 1669-1670, so long as he did not trade with any tribes within 200 miles of Maryland.14

Batts and Fallam crossed through the mountain at Zynodoa (Shenandoah) in 1671. Needham and Arthur passed through the mountains at Sara in 1673.15

A key insight from the expedition was the identification of what the Native Americans desired in exchange for skins and furs. Trading cloth was in the highest demand, followed by "Axes, Hoes, Knives, Sizars, and all sorts of edg'd tools." Guns and ammunition were also highly desired, but such trade would violate restrictions imposed by the colonial government.16

The three explorations by John Lederer and his companions did not lead to an expansion of trade with tribes in the interior of Virginia and North Carolina. Expeditions by Batts, Fallam, Needham and Arthur were equally unproductive in stimulating trade.

John Speed used Lederer's journals for information regarding the Piedmont when he prepared a map of the Carolina in 1676, in which he portrayed what may be the Roanoke River stretching upstream from Albemarle Sound to near Sara

Source: Wikimedia Commons, A New Description of Carolina (by John Speed, 1676)

The economics of extending the fur trading business west of Fort Henry were daunting. Lederer noted that a large number of people would be required to carry trading goods to the Native American towns, and such expeditions would require a security force to prevent theft. Obtaining the necessary capital to purchase trading stock and finance journeys to acquire furs was difficult in Virginia. Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 disrupted the Virginia colony and led to the recall of Governor Berkeley.

In New York, the Dutch and then the English managed to get the Iroquois to serve as middlemen and facilitate delivery of furs from the Great Lakes region to the trading fort at Albany. In Virginia, no tribe assumed that role. The Siouan-speaking Native Americans on the Piedmont, such as the Tutelo, Saponi, and Monacan, were not powerful enough to resist encroachment by the colonists or to block the raids of the Catawba, Cherokee, and Iroquois.

The Virginia tribes were forced to move away, depopulating the Piedmont. Governor Spotswood's solution was to build Fort Christanna in 1714, in hopes of bringing Native American traders closer to the colonial settlements.

John Lederer started his three journeys in the watersheds of the Pamunkey (1), James (2), and Rappahannock (3) rivers

Source: Project Gutenberg, The Discoveries Of John Lederer

in 1718, the pattern of Virginia's rivers and mountains west of the Fall Line was still poorly understood

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Louisiane et du cours du Mississippi (1718)

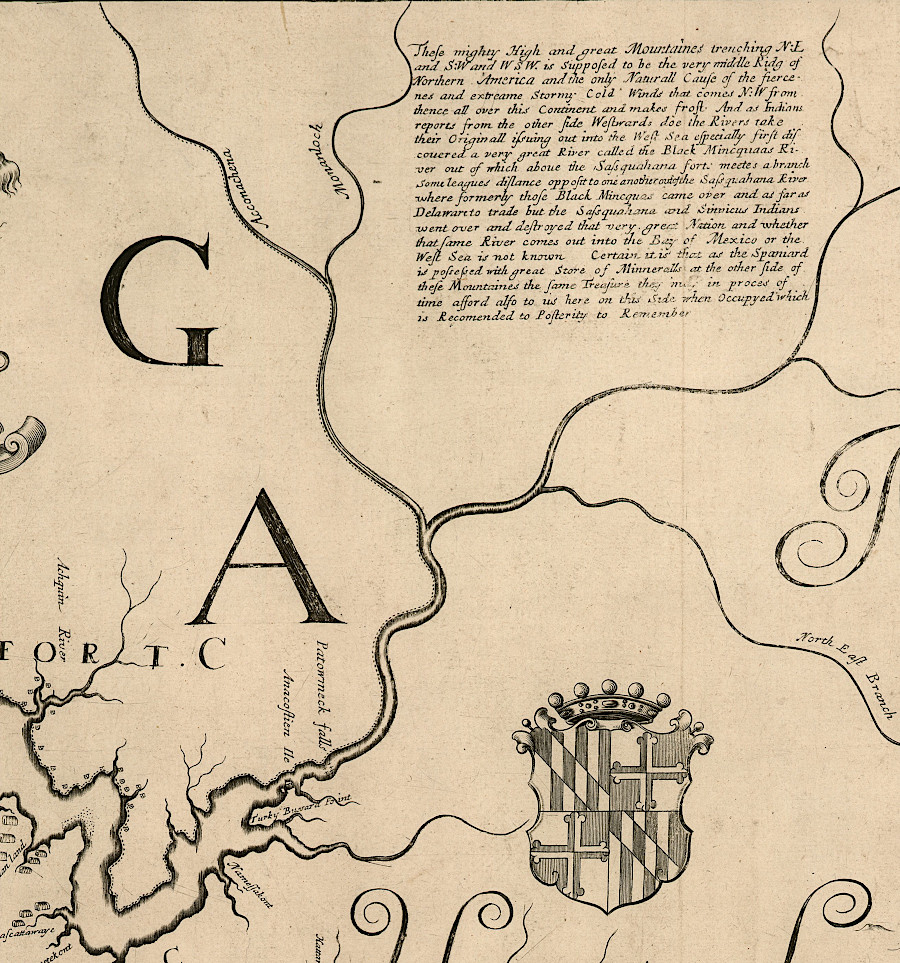

before John Lederer, there was more speculation than understanding regarding the Potomac River upstream from Great (Patowmeck) Falls

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Virginia and Maryland As it is planted and Inhabited this present Year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)