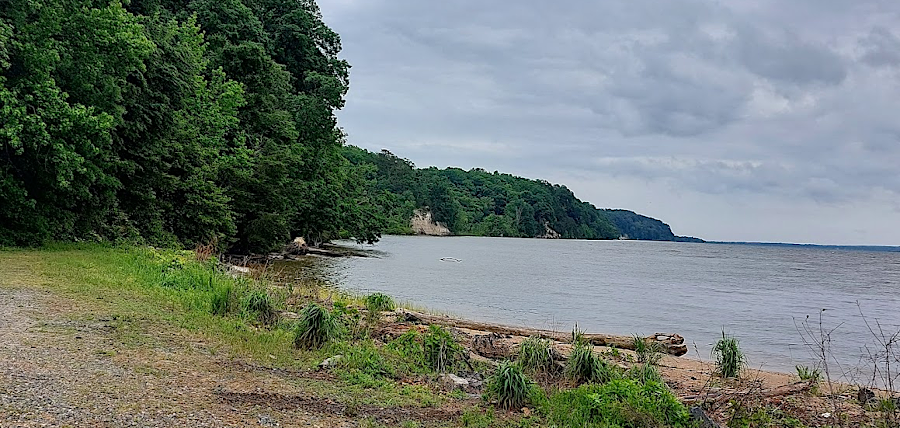

Fones Cliffs stretches for four miles on the north bank of the Rappahannock River, upstream of Warsaw in Richmond County

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fones Cliffs at Rappahannock River Valley NWR (by Paul Welch)

Fones Cliffs stretches for four miles on the north bank of the Rappahannock River, upstream of Warsaw in Richmond County

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fones Cliffs at Rappahannock River Valley NWR (by Paul Welch)

looking south from Carter's Wharf, showing a series of cliffs on the north bank of the Rappahannock River

In 1608, John Smith sailed/rowed for about four miles past what today is known as Fones Cliffs, as he pushed upstream on the Rappahannock River towards what today is Fredericksburg. Smith recorded three towns of the Rappahannock tribe, Wecuppom, Matchopick, and Pissacoack, on the cliffs upstream from Topahanocke.

At the time, there were about 2,100 members of the tribe. The Rappahannocks were part of the North American trading network through which shells from the Chesapeake Bay were exchanged for copper from the Great Lakes.1

Since the first Paleo-Indians arrived in Virginia roughly 20,000 years ago, the vista from Fones Cliffs would have been recognized as a special place and used for spiritual ceremonies.

The cliffs of weakly lithified sand were created before the peak of the most recent Ice Age about 20,000 years ago. As the Rappahannock River carved its current channel, the high-energy outside edge of a river bend created the local topographic feature on the north and low marshes on the southern side of the river.

Fones Cliffs tower 100 feet above the Rappahannock River and low marshes on the southern bank

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Champlain VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2022)

The cliffs formed a tight chokepoint on the river in 1608. Since then, erosion has continued. The Rappahannock River has etched away another 300 or more feet of the cliffs, destroying the original site of the Native American towns while expanding the marshes on the low-energy side of the river bend.

Beverly Marsh, viewed from cliff just south of Carter's Wharf

the cliffs above Carters Wharf are not stable, so the US Fish and Wildlife Service has built a fence to keep visitors away from the crumbling edge

The white sediments in the cliff include more than sand that had eroded off the Appalachian Mountains. The Fones Cliff sediments also include diatomaceous earth, silica that had once coated marine algae (diatoms) living in the Atlantic Ocean. When sea levels were higher, what is now Richmond County was submerged underneath the Atlantic Ocean and the coastline was near modern I-95.

Those sediments in Richmond County are mapped as part of Cobham Bay Member of the Miocene Eastover Formation, part of the Chesapeake Group. They had been deposited over five million years ago during the Miocene Epoch, when sea levels were higher and the Coastal Plain was underwater. As an untold number of diatoms in that Atlantic Ocean died, their shells sank to the bottom. As a result of Rappahannock River erosion, the sediments are exposed now at Fones Cliffs. (Modern diatoms are still so common that they produce 20-30% of the oxygen on earth.)2

the unconsolidated sediments at Fones Cliffs are mapped as part of the Chesapeake Group (TC), deposited when sea levers were higher over 5 million years ago

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geologic map and generalized cross sections of the Coastal Plain and adjacent parts of the Piedmont, Virginia (1989)

The high number of bald eagles living around Fones Cliffs, plus perhaps 20,000 eagles visiting each year to feed on shad, herring and blue catfish during migration, made the site a target for land acquisition by conservation groups. Eagles were attracted by the forested shoreline, offering nesting, perching, and roosting sites next to waters for foraging. The National Audubon Society has designated the Lower Rappahannock River, including Fones Cliffs, as an Important Bird Area.

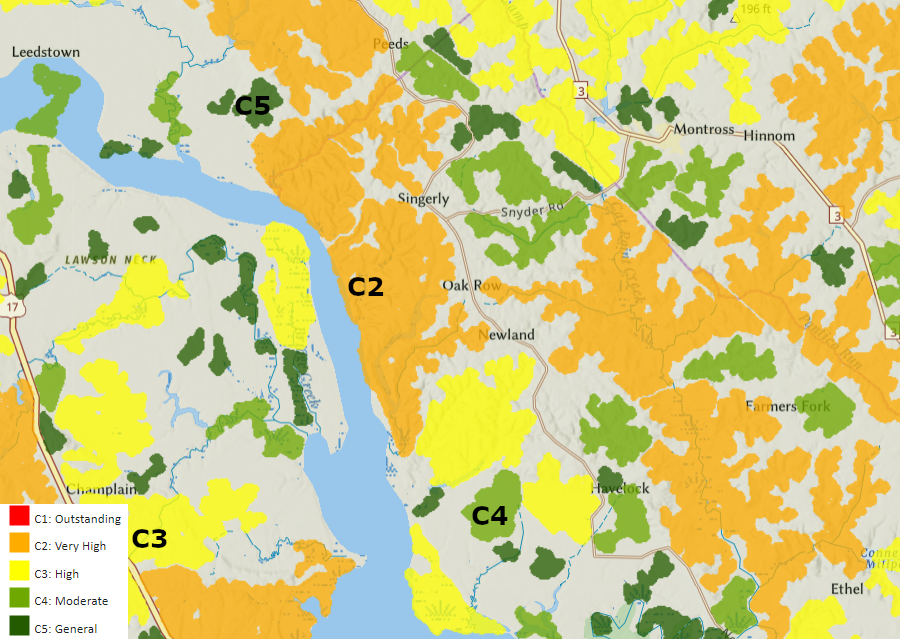

The Virginia Natural Heritage Program categorized the Mixed Mesic Hardwood Forest there as a "Very High" ecological core, Category C2 on a scale of five where C1 was "Outstanding." The state agency mapped the forest around Fones Cliff as a node on the proposed statewide network of natural lands that could be connected by wildlife corridors. The US Fish and Wildlife Service was authorized to acquire 20,000 acres for the Rappahannock River National Wildlife Refuge, which was established in 1996.3

the area around Fones Cliffs is mapped as a C2 (Very High) ecological core

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Natural Heritage Data Explorer

However, the vista made the site attractive for real estate speculation as well. Richmond County officials anticipated new development would generate new property and sale tax revenue. Developers claimed that land where conservation easements limited construction generated $5/acre in property taxes, but building new 3,500-square-foot houses could generate as much as $9,000/acre for the county.

In 2012, Richmond County designated the 252-acre Bowers Tract next to the cliffs for future residential development. In 2015 Richmond County designated another 977 acres tract owned by Diatomite Corporation of America, which proposed to build a resort with a 116-room lodge, restaurant, 18-hole championship golf course, 205 homes, and 513 multi-family units.

Diatomite Corporation of America had originally acquired the property in the 1950's for mining the silica-rich sediments at the site. The material was used for multiple industrial purposes such as purifying beer and as an additive in cement, as well as household purposes such as a kitchen grease cleanser.

Fones Cliffs is a 100' tall layer of white diatomaceous earth located downstream of Leedstown on the Rappahannock River

Source: Chesapeake Conservancy, Fones Cliffs 360

Virginia True Corporation acquired the Diatomite Corporation of America property in 2017, for a $12 million price. Opponents to the development focused initially on the impacts on natural resources, while the developer promised to build monuments recognizing John Smith and the first English settlers who visited Fones Cliff in 1608. The significance of the site to the Rappahannock Tribe became prominent later.4

In 2017, Virginia True Corporation cleared 13 acres next to the river without authorization from the county. The resulting erosion caused 800 feet of the cliff face to slough off into the Rappahannock River in 2018, with trees falling from the top of the cliff. Whatever archeological resources may have remained from the past were destroyed. One of the conservation advocates stated:5

Later in 2018 the Virginia Attorney General filed a lawsuit, saying:6

Virginia True Corporation went into bankruptcy in 2019. In 2020, it proposed an $83 million development plan that included a hotel and luxury condos in 10-story towers, but eliminated the golf course. Housing units would also be constructed for seniors and veterans, using funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality proposed a $200,000 fine for the unauthorized clearing, while conservation advocates suggested $500,000. The bankruptcy court had to determine if the fine was a debt which would be paid in full, in part, or not at all. Part of the challenge for Virginia True Corporation was a claim that the lawyer who negotiated the property sale to Virginia True Corporation had a conflict of interest. He been also the agent for the landowner, who was suffering from Alzheimers.7

Conservation groups, the Rappahannock, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service worked together with hopes of acquiring as much as 2,000 acres at Fones Cliffs. An additional 1,000 acres on the southern bank of the Rappahannock river was also targeted. The Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge had grown to 9,000 acres in 2022 towards its authorized 20,000 acres.

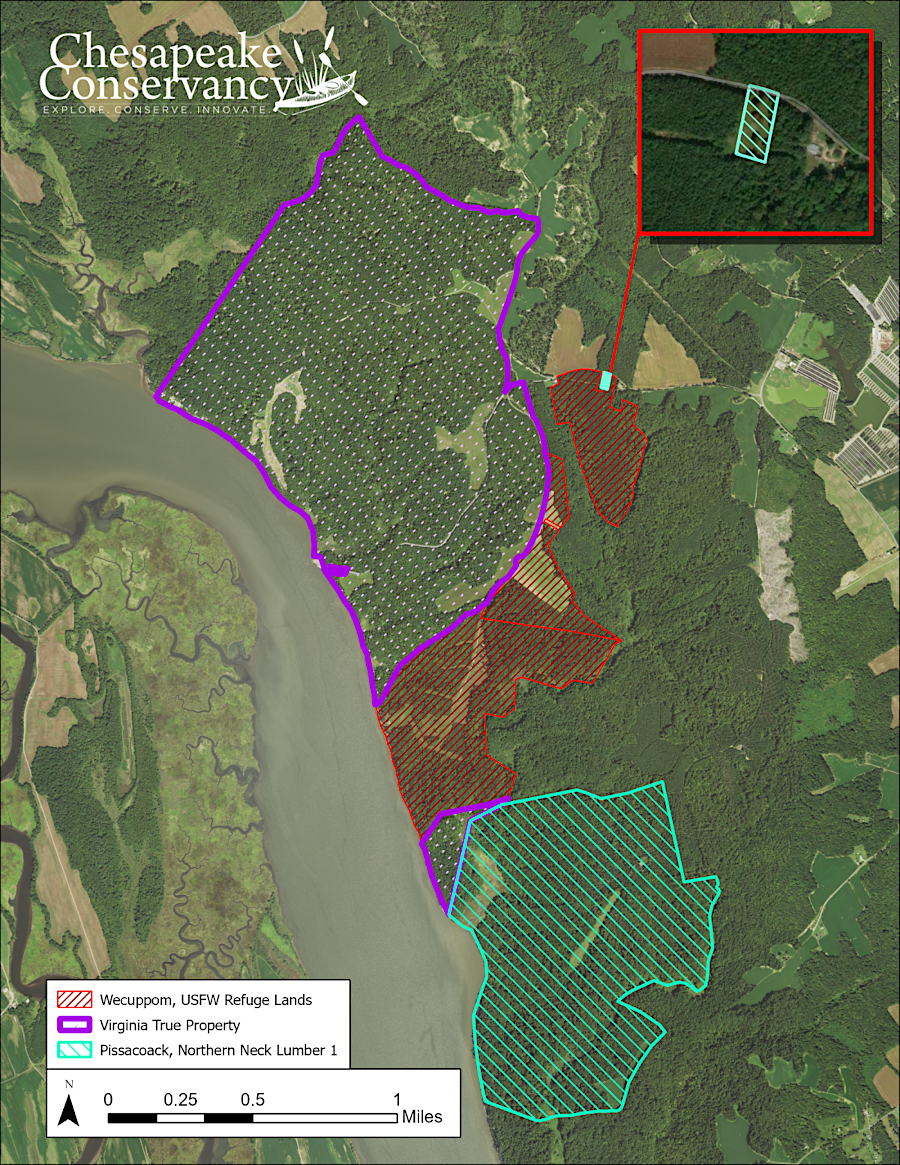

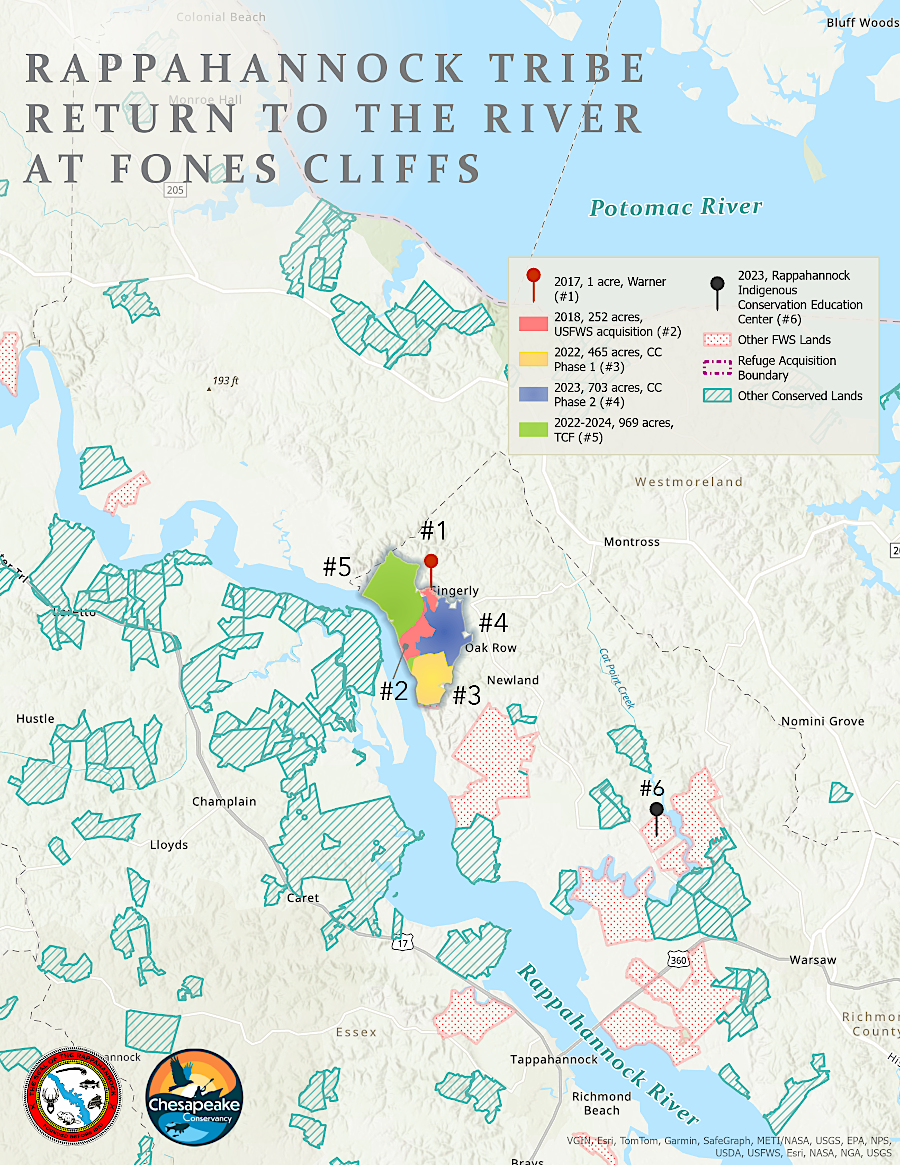

In 2017, the Chesapeake Conservancy used a private donation from the daughter of former Senator John Warner to acquire one acre at Carters Wharf downstream from Fones Cliffs. That parcel was donated to the Rappahannock Tribe for use as a staging area for "Return to the River" program.

In 2018, with the support of the modern Rappahannock Tribe and $4 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, The Conservation Fund purchased the 252-acre Bowers Tract at Fones Cliff. The non-government conservation organization transferred what could have been 45 building lots to the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge in 2019.8

the Chesapeake Conservancy has acquired land at Fones Cliff, then transferred parcels to the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge and the Rappahannock Tribe

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Return to the River (photo by Jeffrey Allenby, Chesapeake Conservancy)

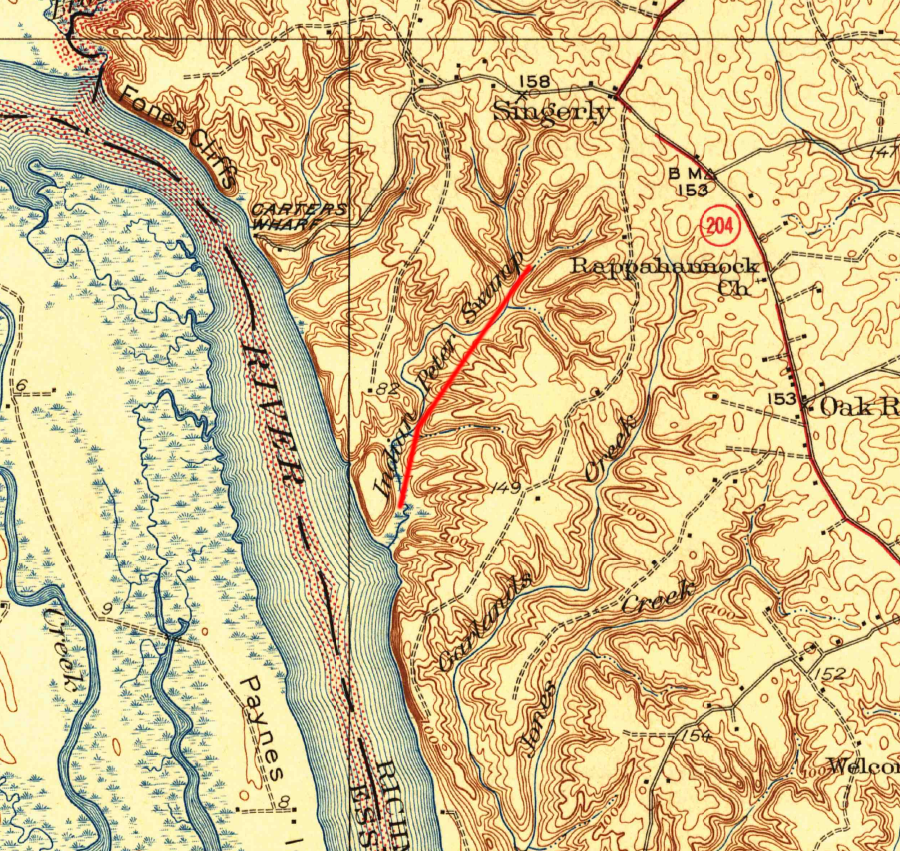

The land added to the Federal wildlife refuge may have included the site where "Indian Peter" lived. Indian Peter was a Rappahannock who had been enslaved and "owned" by a colonist, but was manumitted in 1699. Archeologists have found crystals and other artifacts suggesting where he may have lived from 1700-1730.9

Indian Peter, a once-enslaved Rappahannock Indian, lived near Fones Cliffs

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Wakefield, VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1932)

In 2022, the Chesapeake Conservancy used donations and a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to acquire 465 more acres at Fones Cliffs from the Northern Neck Lumber Company. The Chesapeake Conservancy planned to transfer 703 acres, the Bowers Tract and land at Fones Cliffs in fee title to the tribe and not to the Federal government. Before the land transfer, however, the US Fish and Wildlife Service obtained a permanent conservation easement on the Fones Cliff property.

The tribe re-established the name "Pissacoack" for the site and initially planned to recreate a 1500's Native American town. The land given to the tribe was located within the authorized boundary of the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge. Since the tribe had been Federally recognized in the 2018 Thomasina E. Jordan Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act, it could place the property in "trust" with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.10

in 2022 the Chesapeake Conservancy acquired 465 acres of Fones Cliffs, adjacent to the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge, for transfer to the Rappahannock Tribe

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Return to the River (photo by Jeffrey Allenby, Chesapeake Conservancy)

In 2022, Virginia True Corporation announced plans to sell nearly 1,000 acres next to Fones Cliffs as part of the bankruptcy case. Though the land was technically zoned for just agricultural use, the sale announced:11

The Conservation Fund announced on December 8, 2022 that it had purchased 964 acres, including the site of the Rappahannock tribe's ancient town of Wecuppom, from Virginia True. The Conservation Fund successfully bid at an auction against a development group that included some investors frm Virginia True. They were apparently planning to build housing and a golf course.

The Conservation Fund paid $8.1 million for land that had sold for $12 million in 2015. The Conservation Fund planned to transfer the 964 acres to the Rappahannock Tribe, after selling a permanent conservation easement to the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The strategy of having non-government organizations partner with government agencies to purchase land, establish conservation easements, and then transfer the land to the tribe became a national model.12

One challenge for the land transfer was identifying how provisions in a conservation easement could be enforced. As a Federally-recognized tribe, the Rappahannock are a sovereign nation and could establish their own judicial system. There was no desire on the part of the US Fish and Wildlife Service or The Conservation Fund to go into a Federal court to force compliance with the terms of the easement.

The Rappahannock Tribe relied upon grants and donations to raise the funds needed to complete the land transfer. Between the Chesapeake Conservancy and the Conservation Fund, the tribe ended up owning nearly 1,500 acres of its former territory.13

The tribe's community center in King and Queen County has no access to Rappahannock River. The conservation easement on the former Virginia True parcel did not authorize housing, so the tribe can not move back and live at Fones Cliff.

The easement did authorize development on three small parcels, so there could be facilities for community gatherings on the traditional lands of the tribe. In addition, new structures can be built to store boats near Carter's Wharf, and a public access trailhead with parking could be constructed north of Carter's Wharf. The initial plans to recreate a historic town are likely to be modified into building an education and cultural center.

After establishing the conservation easement, the Conservation Fund transferred the 1,000 acres to the Rappahannock Tribe on April 16, 2025. Today the tribe now controls the land where in 1608 John Smith found them living in the towns of Wecuppom, Matchopick and Pissacoack.14

map depicting the Pissacoak property and two Virginia True parcels purchased by The Conservation Fund in late 2022

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Nearly 1,000 acres of Fones Cliffs to be returned to the Rappahannock Tribe

the Rappahannock Tribe acquired Fones Cliffs through multiple acquisitions by different partners

Source: Chesapeake Conservancy, Fones Cliffs

Fones Cliffs from Carters Wharf in 2024, showing erosion from Virginia True land clearing

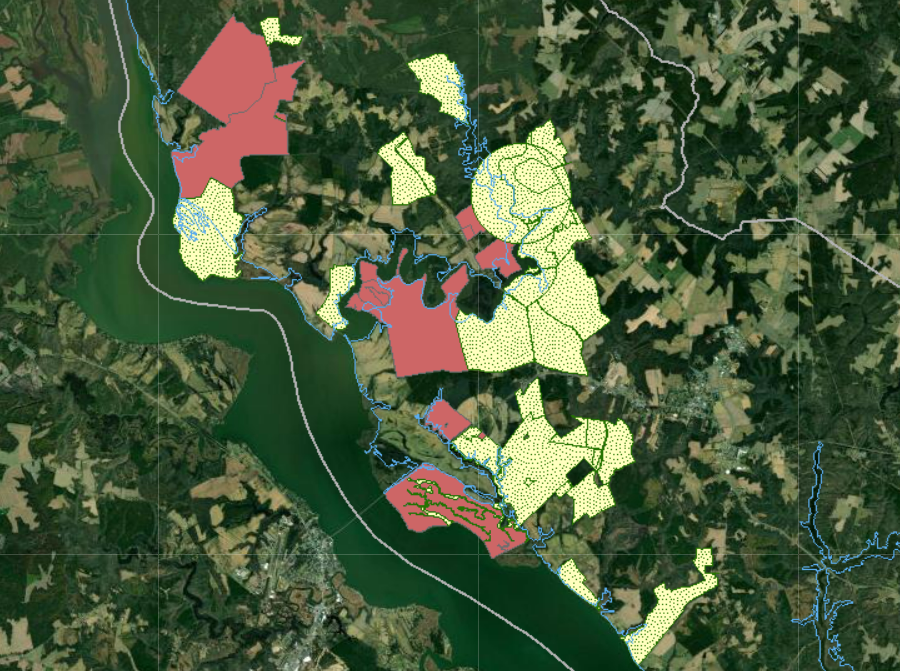

Federal land (brown) and conservation easements (yellow) near Fones Cliffs in early 2022

Source: Richmond County, Comprehensive Map Viewer