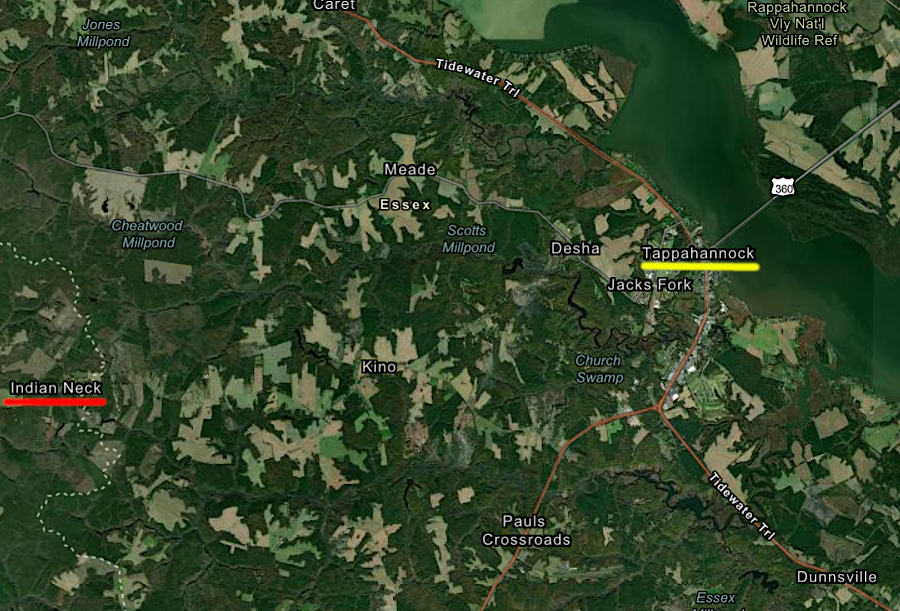

the modern Rappahannock Tribe is concentrated around Indian Neck in King and Queen County, 10 miles away from the ancient capital at Tappahannock

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the modern Rappahannock Tribe is concentrated around Indian Neck in King and Queen County, 10 miles away from the ancient capital at Tappahannock

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The first time the Rappahannock Tribe encountered an English ship in 1603, they welcomed it. However, the captain (possibly Samuel Mace) ended up killing the Rappahannock chief and took captives back to England. The captives carried to London ended up demonstrating canoeing on the Thames River, entertaining the English.

The Rappahannocks forced to cross the Atlantic Ocean were among the 60 indigenous North Americans brought from North America to England between 1576-1630. The canoeists may have died in the plague that ravaged London; they certainly were not returned home. When Shakespeare needed inspiration to create characters in The Tempest about seven years later, he may have drawn upon reports of the canoe demonstration.1

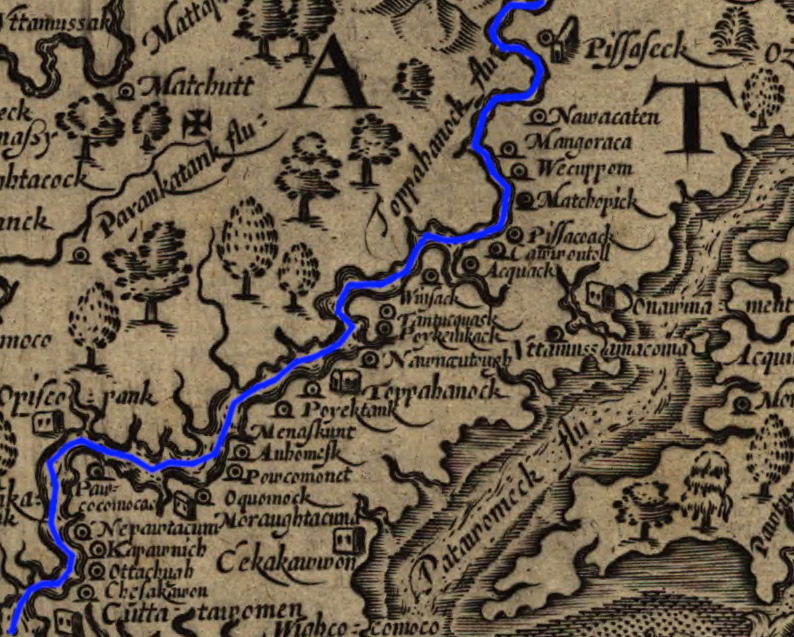

Captain John Smith met the Rappahannock on their home territory in December/January, 1607/1608. The English leader was a prisoner, captured by Powhatan's brother Opechancanough while exploring near the headwaters of the Chickahominy River. Smith was taken to the capital of the Rappahannocks on the Topahanocke (now Rappahannock) River so they could determine if he was the English ship captain who had mudered the tribe's weroance three years earlier.

Smith's short height was his savior; the captain had been tall. After the Rappahannocks indicated they had no desire to punish Smith, he was "saved" by Pocahontas and then released.2

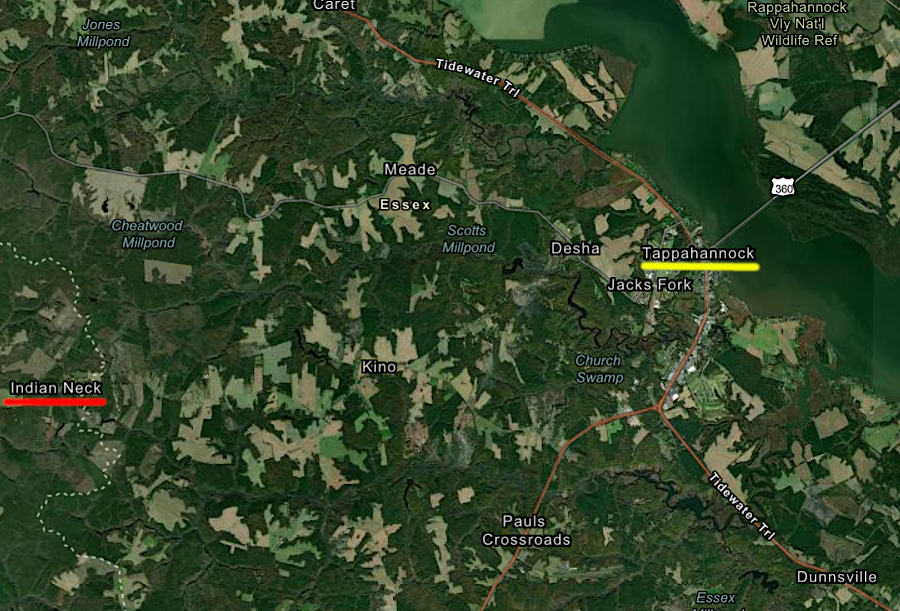

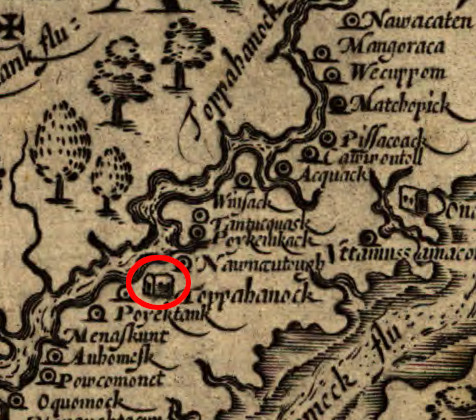

in December 1607, John Smith met the Rappahannocks at their capital town of Topahanocke

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

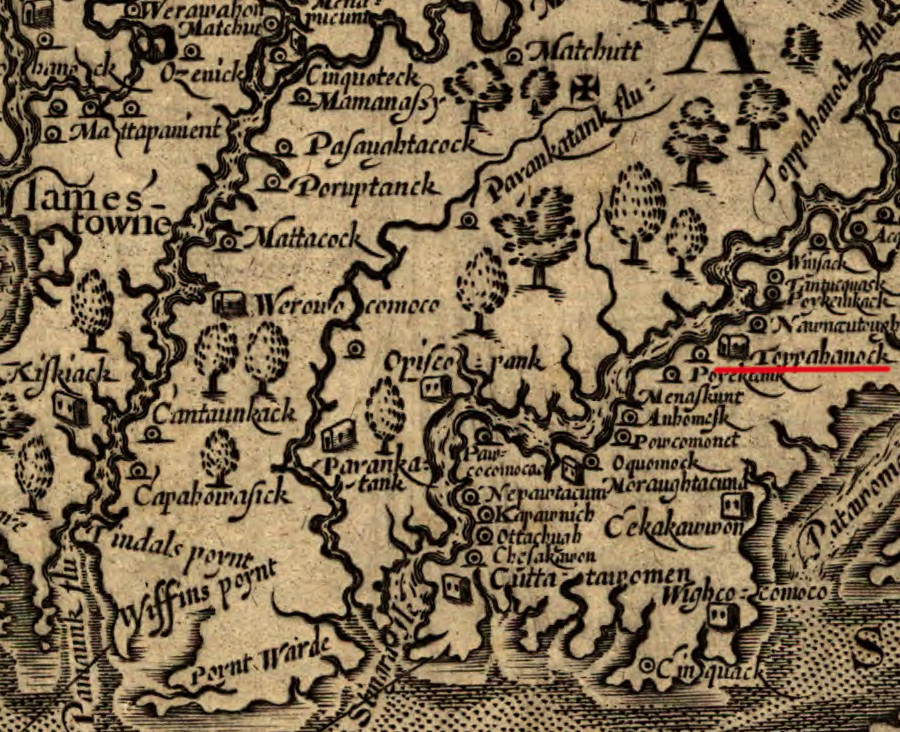

Smith returned to visit the Rappahannocks on his second journey around the Chesapeake Bay in 1608. He learned the Moraughtacunds has stolen three women from the Rappahannocks who lived upstream, and Smith ignored warnings by the Moraughtacunds not to sail further up the river. The Rappahannocks met Smith's shallop with several canoes loaded with material for trade. The English and the Rappahannocks exchanged hostages, a precaution to reduce the risk of attack by either side.

The English hostage, Anas Todkill, warned Smith that there were warriors hiding behind trees preparing an ambush. The Rappahannock hostage tried to swim away, but was killed in the river. The Rappahannocks fired a barrage of arrows at the English; Smith claimed there were 1,000 arrows. The Englishmen on the shallop survived by hiding behind shields acquired previously from the Massawomeck, and used gunfire to disperse the Rappahannocks.

Todkill managed to escape back to the shallop. The English fastened their shields around the edges of their boat and continued upstream. The Rappahannocks also moved upstream, traveling on the southern bank. They organized another attack from the shoreline opposite Fones Cliffs/Pissacoack, but again their arrows did not penetrate the shields.

the Rappahannocks fired arrows from the shoreline opposite Fones Cliff, but failed to stop the English boat from proceeding upstream

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Making peace on the return trip in 1608 was facilitated by other tribes telling the Rappahannocks how the English had defeated the Mannahoac in a fight near modern-day Fredericksburg. Smith negotiated a deal to resolve the theft of the three women, and:3

the English fought with the Rappahannocks while going upstream in August 1608, but on the return trip from Mohaskahod the two sides negotiated peaceful trade

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

The Moraughtacunds would eventually merge with the Rappahannocks. They sold their land claims downstream of the Rappahannocks in 1662. As part of the sale, the roughly 40 Moraughtacund bowmen got a county court to allot them 2,000 acres on Totuskey Creek in traditional Rappahannock territory. The Moraughtacunds migrated from there with the Rappahannocks to live on the Mattaponi River in 1669, after which they lost their distinctive identity.4

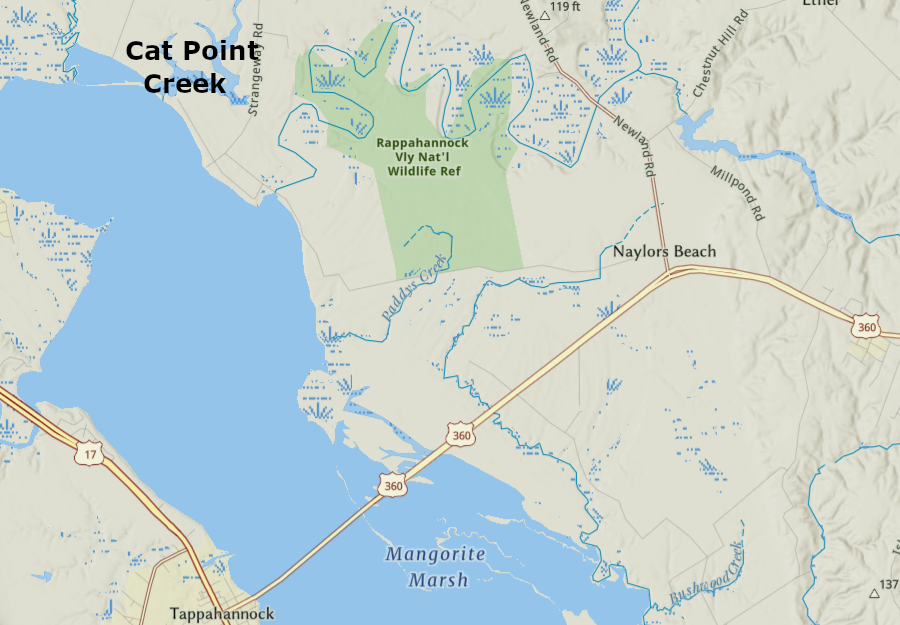

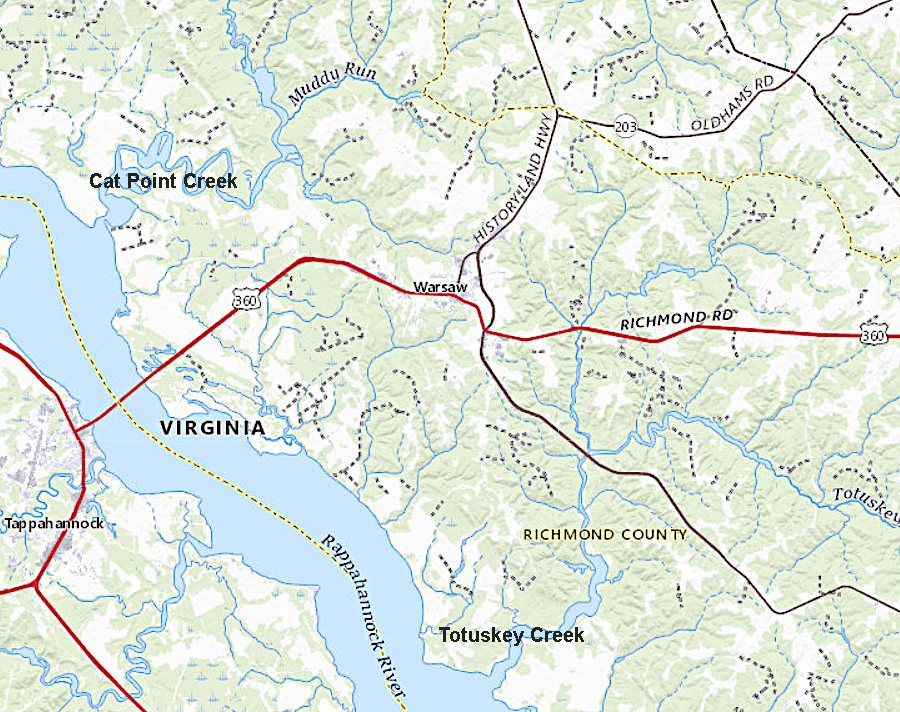

some of the Moraughtacund territory near Cat Point Creek is now part of the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Based on his ethnographic and geographic assessment in 1608, Smith recorded that there were eight Rappahannock weroances with responsibility for 43 towns. The chief lived at Topahanocke, which Smith marked on his map of Virginia with a "king's house."

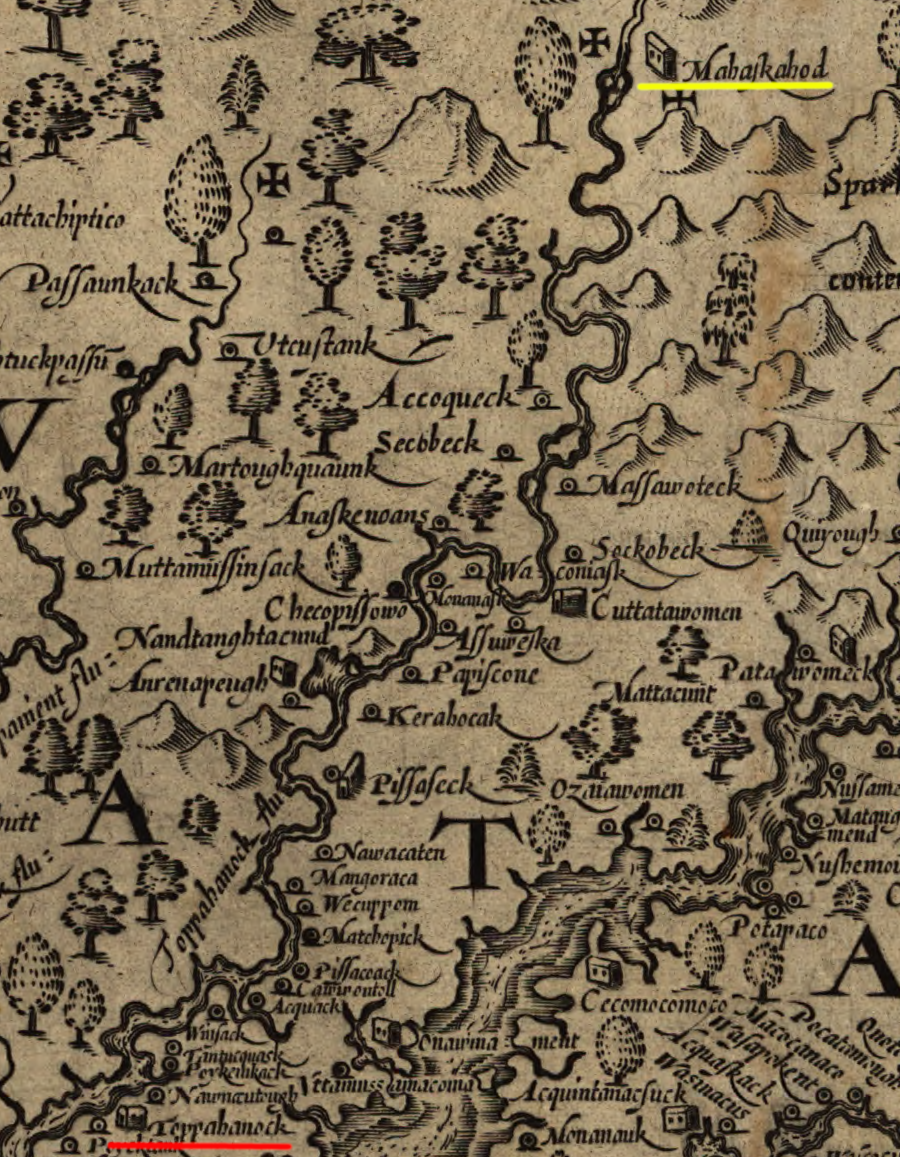

the chief of the Rappahannocks lived at Topahanocke (today spelled Tappahannock)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

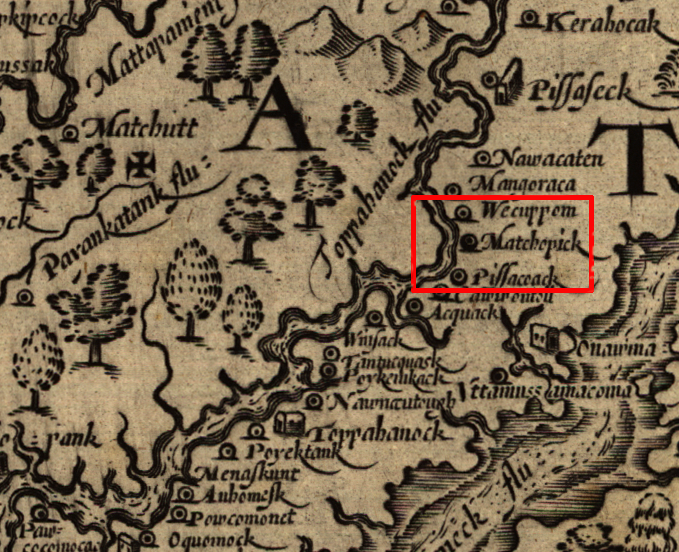

Smith mapped 14 Rappahannock towns on the northern bank of the Rappahannock River. Three of the towns mapped by Smith, Wecuppom, Matchopick, and Pissacoack, were at Fones Cliffs.

three of the towns of the Rappahannocks were on top of Fones Cliffs

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

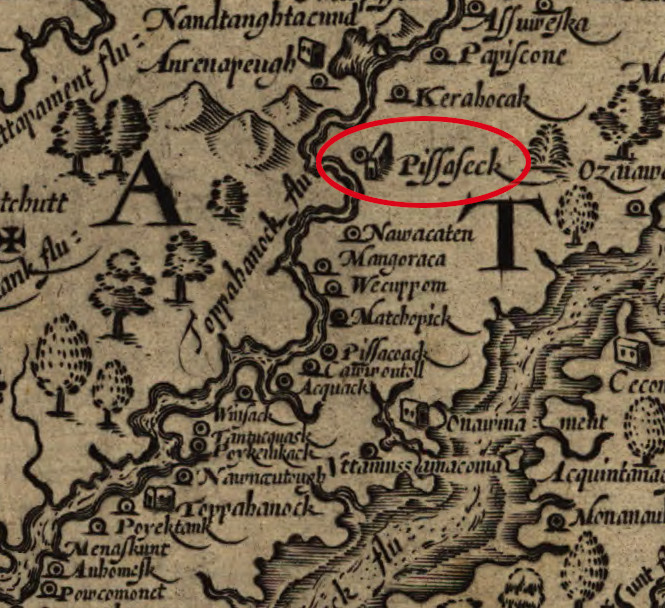

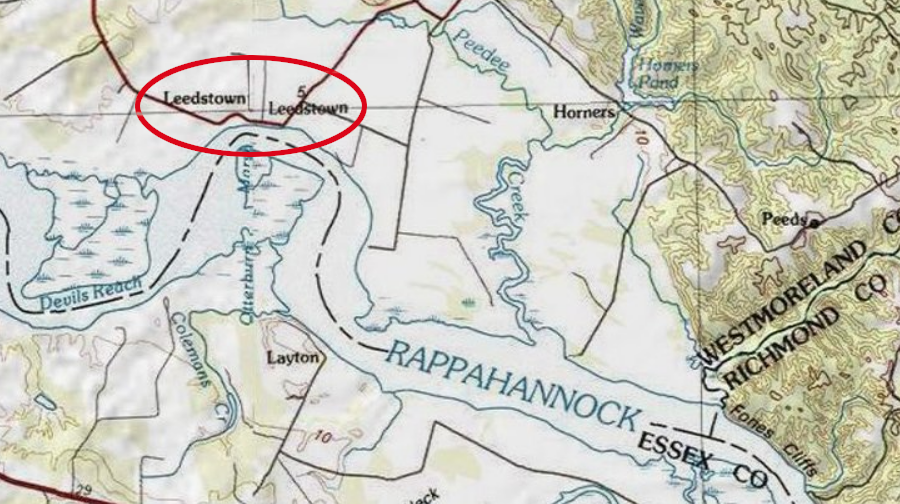

The settlement known in 1608 as Pissaseck is today occupied by the community called Leedstown. The Native Americans who lived there at the time of contact may have been Rappahannocks, or they may have managed to operate as an independent community without allegiance to the Rappahannock weroance. In the mid-1600's, those living at Pissaseck and others in the area coalesced into the Rappahannocks, while different groups merged with the Nanzaticos.5

John Smith mapped Pissaseck at the site of modern-day Leedstown, in Westmoreland County

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624) and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

When the English first arrived, the Rappahannock used both sides of the Rappahannock River for hunting and gathering. The Rappahannocks traditionally used the land on the southern side of the river, closer to the Pamunkey, for hunting grounds. On a seasonal cycle, the king's house and the town of Topahanocke would move to the south side of the river.

However, most towns were located north of the river, with some on top of Fones Cliff. That river may have been used as an extra barrier providing protection against the Pamunkey, the dominant tribe in Powhatan's area of control (Tsenacomoco). Ossuaries storing the bones of Rappahannock tribal leaders were placed on the northern side of the river.

view of marshes on the southern bank of the Rappahannock River, from top of Fones Cliff

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Return to the River

However, Geographic Information System (GIS) modeling reveals that environmental conditions on the northern bank were more favorable for farming towns. Better soil for farming rather than political reasons may have shaped the Native American settlement pattern along the Rappahannock River in the 1500's. English colonists focused on Powhatan and his control over other tribes, but the English may have overestimated his influence as the paramount chief.

One clue that Powhatan and the Rappahannocks were closely aligned as partners in the paramount chiefdom is that Opechancanough brought John Smith to the Rappahannocks when captured at the end of 1607. Powhatan's brother went out of his way to give the Rappahannocks an opportunity to exact revenge on the Englishman.6

John Smith discovered Rappahannock towns were concentrated on the northern bank of the Rappahannock River ("north" is to the right)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

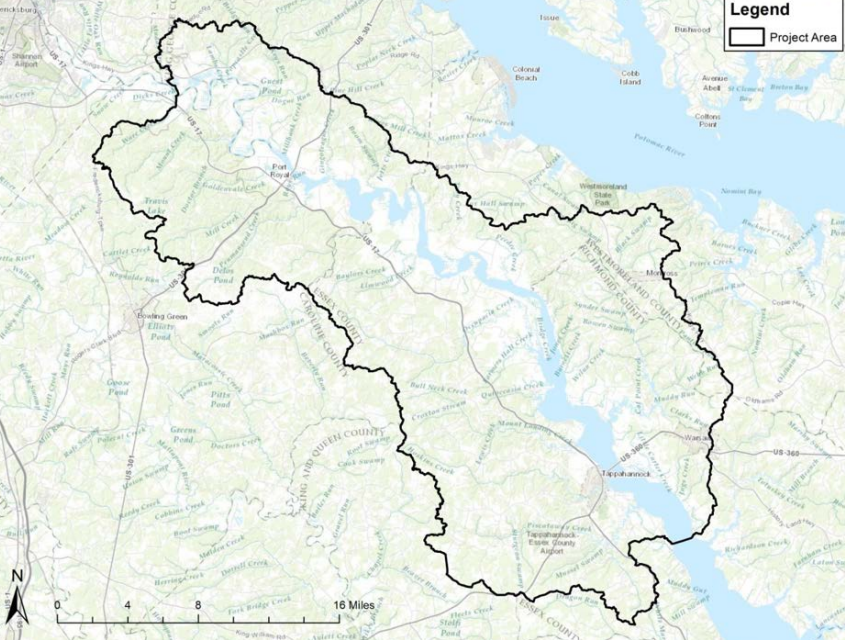

The Native Americans foraged widely along both banks of the Rappahannock River; they stayed in compact towns for just a portion of their day. For better understanding the resources along the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, the National Park Service has identified an Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Rappahannocks that encompassed over 550 square miles.7

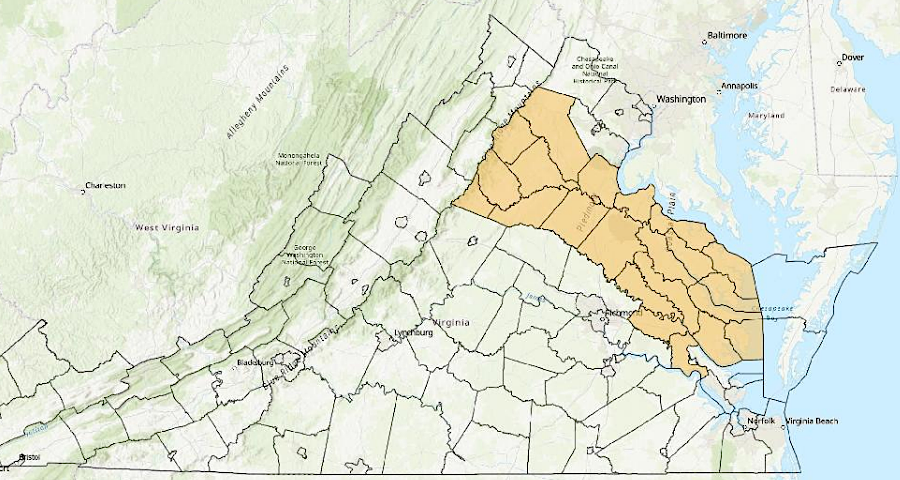

the territory of the Rappahannocks may have included over 550 square miles

Source: National Park Service, Defining the Rappahannock Indigenous Cultural Landscape (Figure 2)

Colonial settlement advanced up the Rappahannock River after the failure of the 1644 uprising led by Opechancanough, and Necotowance signed a treaty in 1646 to end the Third Anglo-Powhatan War. To avoid the land-hungry and aggressive English settlers, the Rappahannocks began to hunt and farm on just the northern side of the Rappahannock River.

Peaceful accommodation and separation was not successful; the English were not willing to stay south of the river. In 1651 the Rappahannock weroance Accopatough signed a deed to sell some of the land on the northern bank. He sold all the land that was east (downstream) of Totuskey Creek to Moore Faultleroy. Accopatough soon died, but his successor Taweeren and another man who may have been the Moraughtacund weroance traveled to Jamestown to confirm the deed.

English settlers patented more land, moving further upstream on the northern bank of the Rappahannock River. The Rappahannocks retreated further up the Rappahannock River first, then returned to their traditional hunting territory south of the river.8

By 1652, the tribe's primary town was two miles upstream of Cat Point Creek. The General Assembly authorized colonists to patent all the land within the Rappahannock River watershed in 1653, after enough land had been allotted (reserved) to all the Native Americans. At the time, England was fighting a full-scale civil war and the royal governor in Virginia, Sir William Berkeley, had been displaced. However, the Virginia gentry were united in their desire to acquire more land no matter who was in charge of the colonial government.

Lancaster County quickly negotiated a deal with the Rappahannocks, including a promise to build the chief an English-style house. The allotment of land did not result in peaceful coexistence between the settlers and Native Americans. There were enough conflicts for the militia of Lancaster, Westmoreland, and Northumberland counties to demand the Rappahannocks compensate settlers for damage to their livestock and crops. A meeting with the Rappahannocks ended in violence, and weroance Taweeren was killed.

Enough colonists moved into the Rappahannock watershed to justify the creation of a new county. The judges of the original Rappahannock Count court reached their own deal with the tribe in 1656. The General Assembly affirmed in 1658 that enough land would be allotted for each bowman to have 50 acres.

the original Rappahannock County (orange) was created in 1656, carved out of Lancaster County (red)

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

As the English started to establish farms north of the Rappahannock River in the 1650's, the Rappahannocks, the Moraughtacunds, and the Totuskeys living in the area were forced to live together.

Moore Faultleroy, who purchased the Rappahannock's land downstream of Totuskey Creek in 1651 from the weroance Accopatough, failed to pay the tribe. Despite that failure, Governor Samuel Mathews (serving in that role during a portion of the Commonwealth while civil war continued in England) granted Faultleroy the right to hunt upstream of Totuskey Creek. Moore Faultleroy was authorized to hunt all the way to Cat Point Creek.

After Samuels died, Sir William Berkeley resumed the role of Governor and the General Assembly demanded to see the deed of purchase from the Rappahannocks. In 1661, the General Assembly demanded that Moore Faultleroy complete his promised payment to the tribe.

He responded by jailing the weroance rather than making the payment. The General Assembly then forced Faultleroy out of his official positions in Rappahannock County, and a colonial commission defined the boundaries for the Rappahannocks. The western edge was Cat Point Creek, and the eastern edge was Totuskey Creek.

the General Assembly defined the territory of the Rappahannocks as the land between Cat Point Creek and Totuskey Creek in 1662

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

By 1669, the Rappahannocks had moved west to the headwaters of the Mattaponi River, beyond daily interactions with colonists. They sacrificed access to their farms and towns, traditional hunting grounds, special spiritual areas, and ossuaries with bones of previous leaders. While on the Mattaponi, the population of the Rappahannocks was reduced to just 30 bowmen, less than 100 people total.9

After Bacon's Rebellion, Cockacoeske signed the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677. She signed for the Rappahannocks, but despite the efforts of Virginia officials the tribe refused to sign that treaty directly or acknowledge the Pamunkey chief as their ruler.

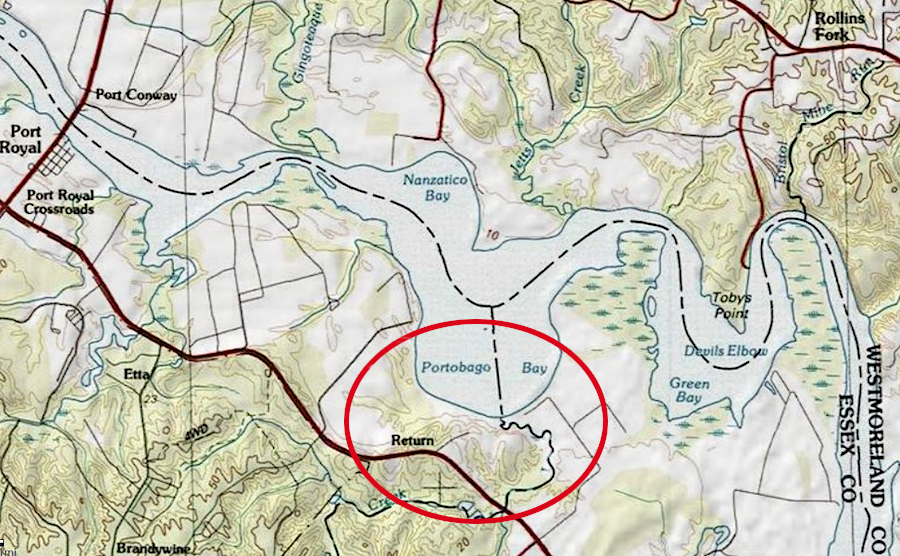

The colonial government identified 3,474 acres for the Rappahannocks in 1682, but then in 1683 forced them to merge with the Nanzaticos. The Rappahannocks were relocated by the Essex County militia to the Portobago Indian Town on the Rappahannock River. Ocean-going ships could not navigate above Portobago Bay easily, so the colonists were pushing the Rappahannocks beyond the edge of land suitable for growing tobacco for export to Europe. They were also placed where, together with the Nanzatico, they would be more exposed to raids by the Iroquois.

In 1705, the Nanzatico living across the Rappahannock River on the northern bank were seized and sold into slavery. The land at Portobago was sold to colonial settlers, and in 1706 the remnants of the Rappahannock returned back to their traditional hunting grounds in King and Queen County. Removal of the Nanzatico left the Rappahannock as the dominant tribe in the Rappahannock River valley.10

the Rappahannocks were forced off their reservation in 1683 and moved to Portobago, then displaced from there in 1706

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The tribe incorporated in 1921. That gave the members the ability to navigate Virginia laws as a business, and to possess property as a community rather than as individuals. The Rappahannock Indian Baptist Church was founded in 1964, and the General Assembly included the Rappahannocks as one of the first state-recognized tribes in 1983. The tribe purchased 120 acres to build housing for its members in 1998. That land was not established as a reservation by state or Federal government. Instead, it was an investment by the tribe in its community.11

Anne Richardson became chief of the Rappahannock Tribe in 1998. She had been born in the chief's house and was the fourth in her family to serve in that role, but the first female chief in Virginia in over three centuries.12

She was still chief in 2018 when the tribe gained Federal recognition. The administrative process of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in the US Department of the Interior, required demonstration of cultural continuity as a tribe.

Colonists had not eliminated the Rappahannocks, but they maintained a low profile after being forced out of Portobago in 1706. Conflicts with neighbors were resolved quietly at the local level, and tribal members minimized the time they might spend in court or with government agencies generating official records. In the 1920's, Walter Plecker in Bureau of Vital Statistics sought to deny the existence of Native Americans in Virginia, declaring that they were all "colored" and should comply with white/colored segregation laws rather than claim a third status.

The lack of official records blocked recognition through the administrative process. The solution was to gain Federal recognition through legislation. Passage of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act took 18 years, but the US Congress approved it and President Donald Trump signed it in 2019. The tribe had approximately 100 members and owned less than 200 acres then, compared to the 350,000 acres controlled by roughly 2,400 members when colonists arrived.13

Acquisition of land around Fones Cliffs for conservation included transfer of some parcels to the Rappahannock. A donor gifted one acre in 2017 at Carter's Wharf near Fones Cliffs, enhancing the capacity of the tribe's "Return to the River" program. In a ceremony honoring the transfer, Chief Ann Richardson stated that the acquisition was:14

In 2018, the Chesapeake Conservancy acquired the 252-acre Bowers Tract at Fones Cliff. The property included the land where "Indian Peter" may have lived between 1700-1730. He was a Native American and perhaps a Rappahannock, who had been enslaved by a colonist but then manumitted in 1699. The Chesapeake Conservancy granted that land to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, to be included in the Rappahannock River National Wildlife Refuge.15

In 2022, the Chesapeake Conservancy acquired a additional 465 acres at Fones Neck that included the site of the town of Pissacoack. It was one of three Rappahannock towns, along with Wecuppom and Matchopick, mapped by John Smith in 1608 at Fones Cliffs. That property was given to the tribe, after placing a conservation easement on the tract held by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 2023 the US Fish and Wildlife Service transferred Cat Point Creek Lodge to the tribe, for conversion into the Indigenous Environmental and Conservation Education Center. That structure had been acquired as part of the Cat Point Creek Unit purchase in 2017.

Since the Rappahannocks were officially recognized as a Federal tribe after 2018, they had the option to place the land they owned "in trust" with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the US Department of the Interior.16

In 2025, the Conservation Fund officially transferred 1,000 acres to the tribe. The property had been purchased for $8.1 million at auction after plans by the Virginia True Corporation to build a golf course and resort failed. After that transfer:17

Archeologists from St. Mary's College of Maryland, using Smith's maps, land deeds, and oral history from tribal members, found sites that may identify the locations of the three towns the English noted in 1608. Stone tools, pottery, beads and pieces of pipes were excavated on Fones Cliff. Chief Anne Richardson put the discovery into context:17

the US Fish and Wildlife Service transferred Cat Point Creek Lodge to the Rappahannock Tribe in 2023

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge’s Cat Point Creek Lodge transferred to the Rappahannock Tribe of Virginia

Source: James Monroe Museum, Rappahannock Indian History in the Colonial Period

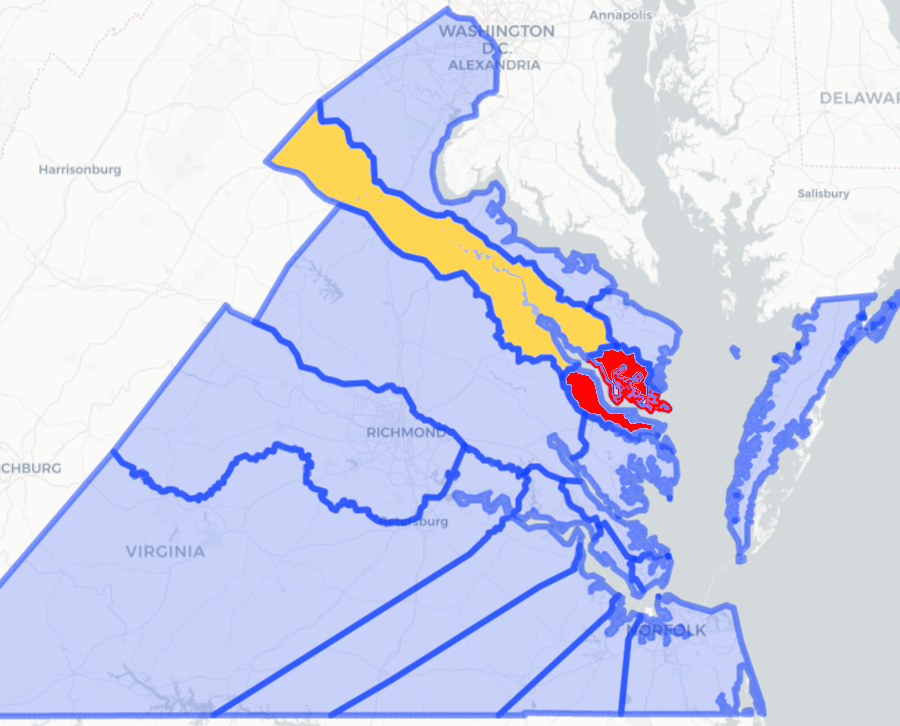

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Rappahannock tribe should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation