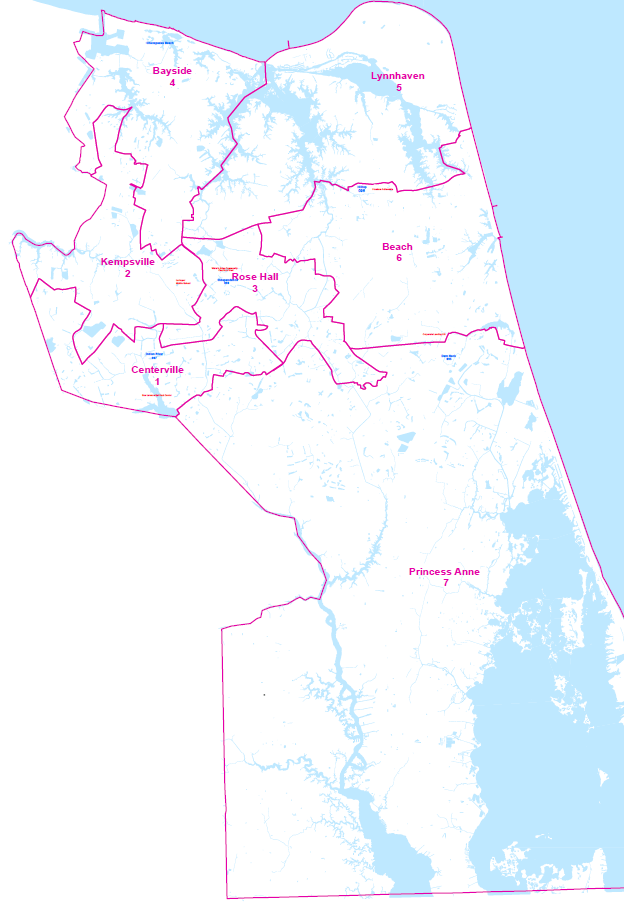

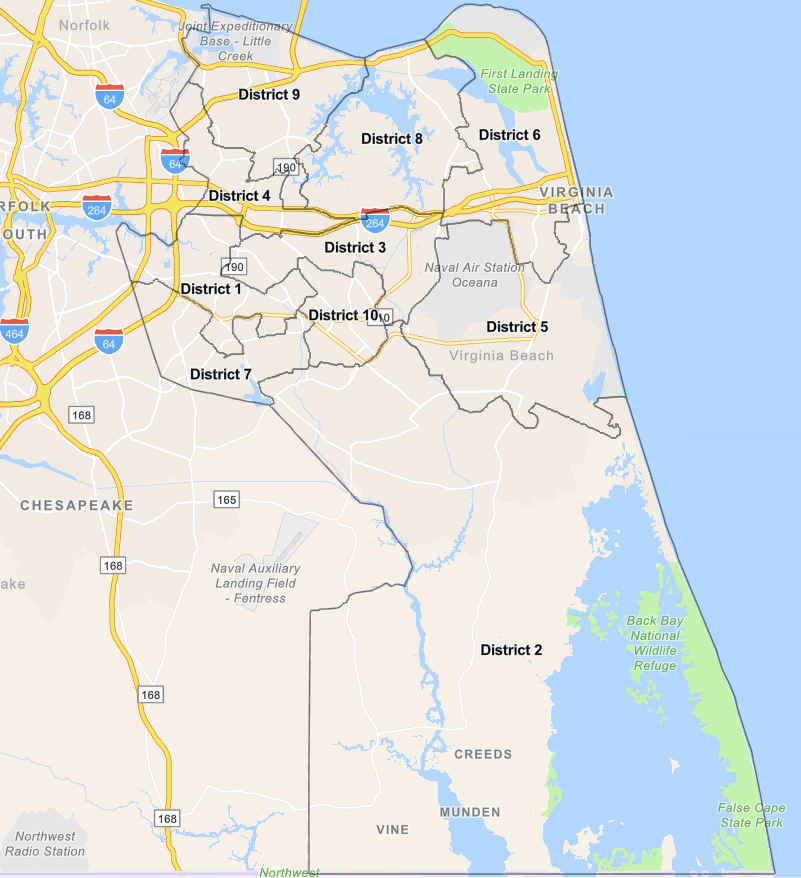

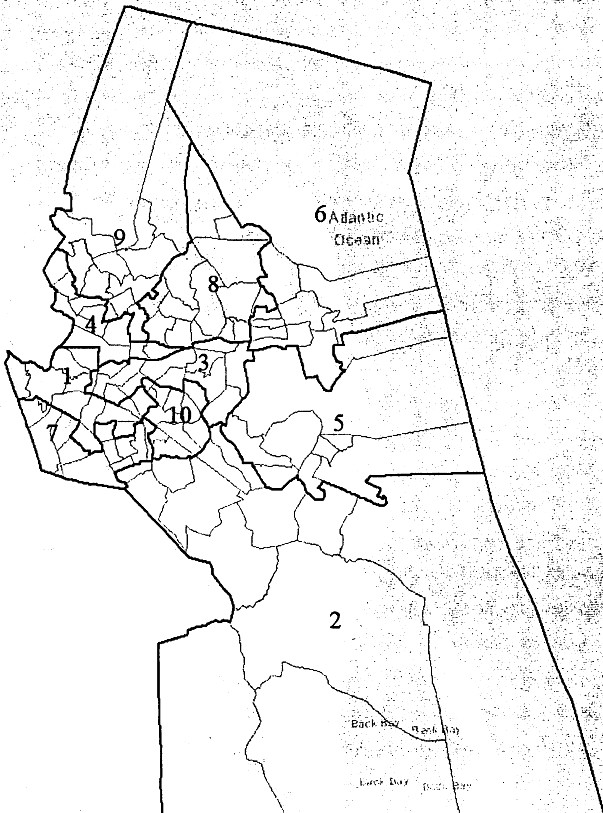

Virginia Beach had seven single-member districts for city council elections between 1966-2021, while three City Council members and a mayor were elected at-large

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Local Election Districts (as of 2015)

Virginia Beach had seven single-member districts for city council elections between 1966-2021, while three City Council members and a mayor were elected at-large

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Local Election Districts (as of 2015)

In 1952 the Town of Virginia Beach became an independent city, separate from Princess Anne County. The two jurisdictions merged in 1963, a step with prevented the City of Norfolk from annexing any part of Princess Anne County.

The new city had an 11-member City Council. The pre-1963 boundaries of the City of Virginia Beach became one electoral district in the merged jurisdiction, and the "old" City of Virginia Beach was given five seats on the new City Council. In addition, one seat was established for each of the six magisterial districts in the old Princess Anne County.

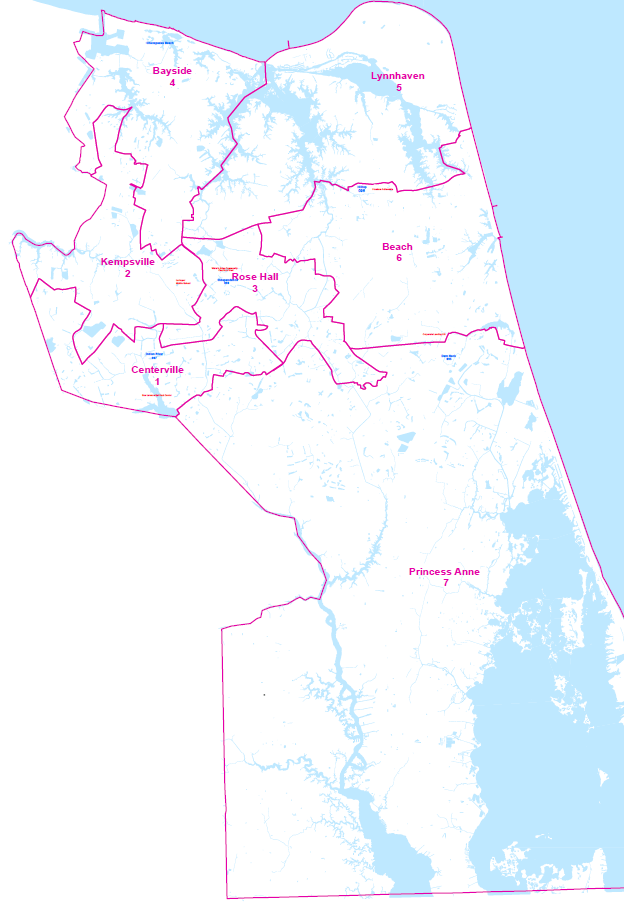

The election districts had significantly different populations; the smallest district (Blackwater) had less than 3% of the population of the largest district (Bayside). When Federal courts established the one-person, one-vote principle in 1965, the voting structure in Virginia Beach was no longer acceptable.

courts objected to the population imbalances between election districts in Virginia Beach, as defined between 1963-66

Source: US Supreme Court, Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S. 112 (1967)

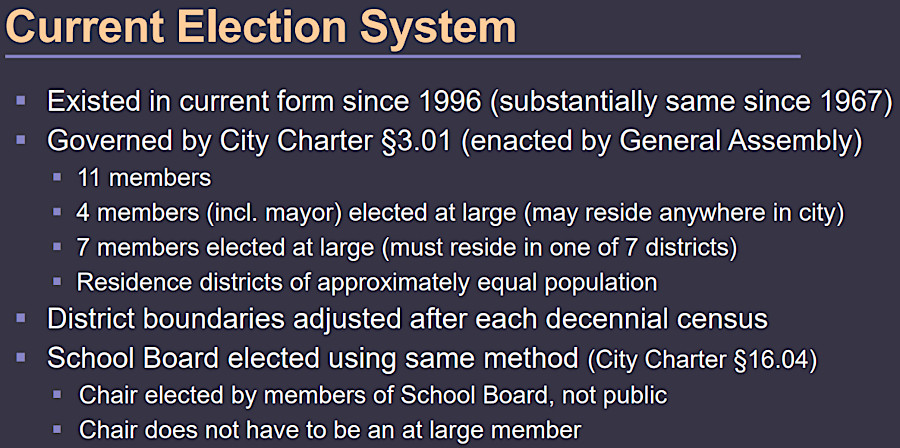

The General Assembly modified the city's charter to respond to the one-person, one-vote problem. The City Council was kept at 11 members, but boundaries of the seven voting districts were revised. The new voting districts were created to have a roughly equal population. In addition, the modified charter created an additional four seats to be elected at-large. Candidates running in the seven districts had to live within those districts, but voters across the city cast ballots for all 11 seats.

Starting in 1966, all residents could vote for all 11 members. All of Virginia Beach became a multi-member district for City Council and School Board elections.

A voter's residence within the city did not limit their ability to vote for every member of City Council, but there were geographic restrictions on the candidates. A candidate running to represent one of the seven defined magisterial districts, rather than running for one of the four at-large seats, had to live within the boundaries of that particular district.

A legal objection to the Seven-Four system reached the US Supreme Court. In 1967, it ruled that the four at-large districts provided a reasonable balance between concerns of urban and rural areas in the city and did not obviously discriminate against minorities, but agreed with an earlier District Court decision that:1

Until 1988, the City Council members chose the mayor. Afterwards, one of the at-large seats was designated for the mayor's race. The School Board continued to select its chair, so there was no special race for that office.2

The use of multi-member districts for elections was common across the United States, but declined after the 1960's. Federal courts ruled that minority voting rights had to be protected, and in many cases multi-member districts were a violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because such districts ensured that only whites would be elected to every seat. Virginia ended the use of multi-member districts to elect members of the General Assembly after the 1980 Census. By 2021, Prince George County was the only one of the 95 counties in Virginia that elected local supervisors from multi-member districts.3

In 2018, about 20% of the population in Virginia Beach was black - but all 11 of the City Council Members were white. A black woman had been elected in 2012 to represent the Kempsville District, but she was defeated by a white candidate in 2016. By 2020 two members were black, but only five black members had been elected since the voting districts were established in 1966.4

In 1990, the US Supreme Court upheld lower court decisions that required Norfolk to change its election process. All seven members of the Norfolk City Council had been elected at-large, and the council then appointed the mayor. Federal courts ruled that the at-large process diluted the voting power of racial minorities, violating the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Norfolk then defined seven wards, three of which had a majority of black residents, and in the next election three blacks won seats on City Council.

An eighth seat was created after a 2000 referendum in which 82% of the voters supported electing the mayor. The Norfolk mayor was elected at-large starting in 2004, and in 2009 a Federal judge affirmed that the at-large process for that seat was legal.5

Voters in Newport News approved a 1987 referendum to elect the mayor at-large, rather than have the city council appoint the mayor from among its members who were also elected at-large. The US Department of Justice blocked the change, arguing that it diluted minority voting power. Blacks were elected in Newport News between 1970-1990, but the 1990 election had created an all-white City Council in a city where one-third of the population was black.

Despite election of another black member of City Council in 1992, the Federal government demanded Newport News adopt a ward system for City Council and School Board elections starting in 1994. Three wards were created, with one in the southeastern corner of the city designed to facilitate election of a minority candidate, plus a seventh seat for a mayor elected at-large. The winner of the 1994 race for a School Board seat, a black woman, said:6

In Hampton, two districts were created in 1994 for School Board elections, with three members elected in each district. A seventh member was elected at-large. The elections for the six seats on Hampton City Council plus the mayor remained at-large.

A Blue Ribbon Commission organized in 1995 to advocate for creating wards to replace the city's at-large election process. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia declined to block the scheduled 1996 election based on claims that the at-large system diluted minority voting power unconstitutionally. In that 1996 election, two blacks ended up winning seats on the seven-member council, undercutting the argument that at-large elections diluted the political power of minority voters.

Holding at-large elections for City Council but district-based elections for the Hampton School Board was confusing. in 2016, the city changed the School Board elections to be at-large, eliminating the two districts.7

Hampton has maintained at-large elections for the six members of City Council plus the mayor. In 2021, only three of the seven members of City Council and only one member of the School Board were white.

The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ruling in 1996 noted:8

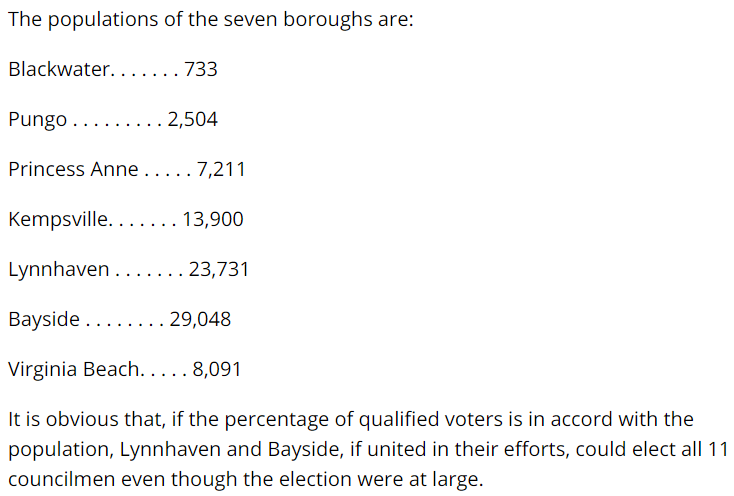

in 2021, the racial composition of the Hampton City Council was consistent with the 2020 Census statistics

Source: Bureau of Census, QuickFacts - Hampton city, Virginia

Virginia Beach was the last jurisdiction in Hampton Roads to have a Federal judge require modifications in election district boundaries in order to comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In a 1994 referendum, voters had endorsed having city council members elected from specific districts. In 1995 the General Assembly passed legislation requiring that the seven districts have equal population, but the state legislature did not require the city to establish wards with voters casting ballots for just candidates within one ward (plus the at-large mayor).

To allay concerns that the question on the ballot in 1994 was confusing, another referendum was held in 1996. The vote that year was decisively in favor of retaining the current system. A US District judge upheld the legality of the Virginia Beach residency districts in 1997.9

Virginia Beach's election system lasted between 1966-2021

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Potential Changes to City’s Election System (May 11, 2021)

In 2017 Latasha Holloway, a resident of Virginia Beach, filed a lawsuit to force a change in the Virginia Beach election process. She pursued the case for 10 months on her own initiative, using free legal advice from a Legal Aid program, until the Campaign Legal Center provided professional legal counsel. A co-plaintiff, Georgia Allen, was added to the case. She had received about 70% of all minority votes but only 20% of the white vote in a 2008 race for an at-large seat on City Council, and lost to a white incumbent.

The Holloway et al. v. City of Virginia Beach lawsuit stated:10

As the lawsuit progressed, City Council debated holding another non-binding referendum to allow the public to express its preference. In 2020, the Virginia Beach City Council decided in a 5-6 vote that no referendum would be held that year.11

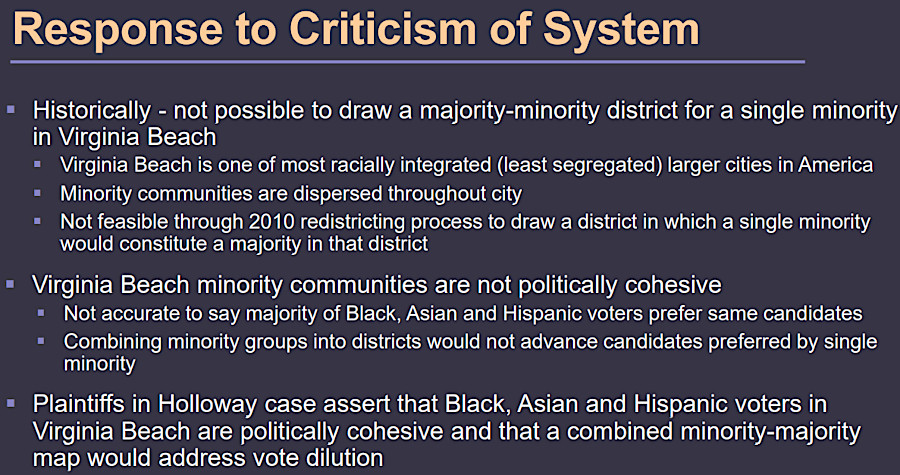

The city objected to claims that the Black, Asian and Hispanic voters in Virginia Beach were politically cohesive, and that defining wards with a majority of non-white voters would address vote dilution. It claimed that the residential patterns made it impossible to draw district boundaries that would have a majority on non-white residents, a "majority-minority" district.12

Virginia Beach officials claimed it was not possible to draw boundaries to create a majority-minority district

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Potential Changes to City’s Election System (May 11, 2021)

U.S. District Judge Raymond Jackson of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ruled in the 2021 Holloway et al. vs. City of Virginia Beach case that the Virginia Beach election districts violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Allowing all residents to vote for all 11 members of City Council denied Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians equal access to the electoral and political process. When the US Supreme Court upheld the district voting system in 1967, the judges had identified the possibility that at a later time other judges might rule the Voting Rights Act was being violated and require corrective action.

Two-thirds of the city's population was white in 2020, but the percentage of white city council members was far higher. By 2021, a Federal judge had finally ruled that the 1966 system violated Federal law. Allowing all voters to elect all 11 City Council members limited the political voice of minorities. As described in a news story:13

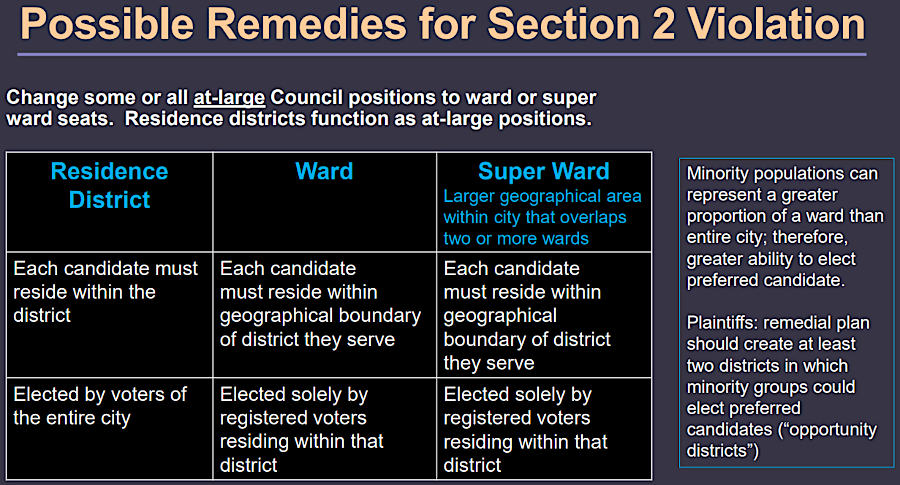

The Virginia Beach City Council opposed the solution recommended by the plaintiffs, creating 10 single-member wards plus a mayor elected city-wide. If 10 single-member districts were required, then all 10 City Council candidates would have to live within the boundaries of the ward they sought to represent. Residents of each ward would vote for just one representative, plus the at-large mayor.

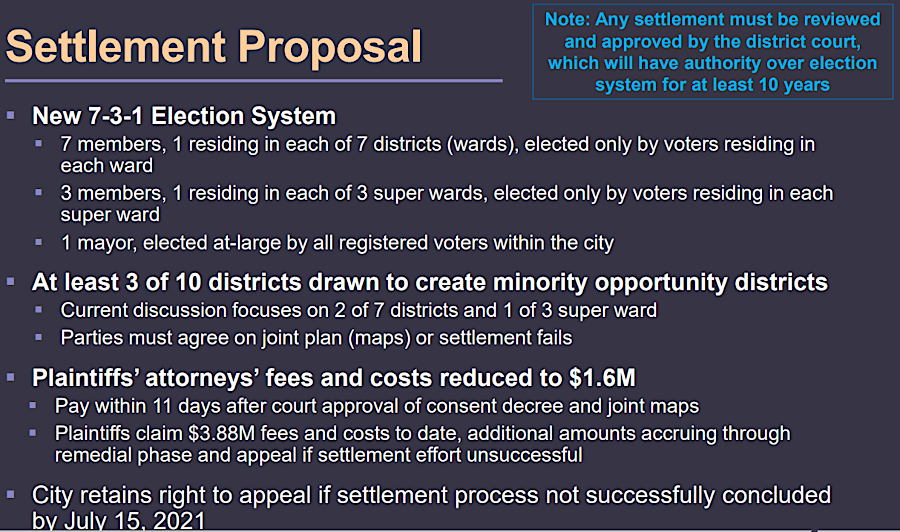

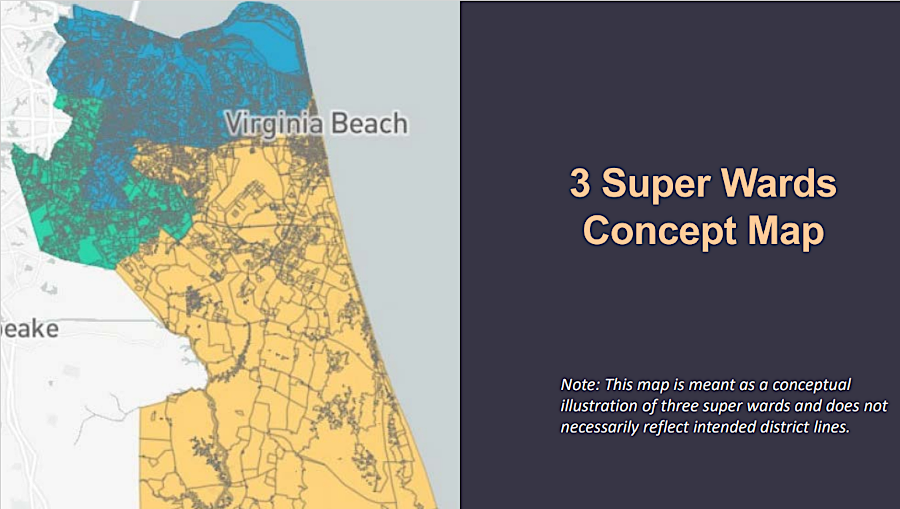

The incumbents on City Council proposed a 7-3-1 alternative to the 10-1 proposal. The city would retain the seven existing single-member districts and draw three additional larger "super wards," each with boundaries encompassing a third of the city's population. The mayor would be elected in the only city-wide vote. Under that arrangement, residents could cast three votes - one for their district councilmember, one for their super ward councilmember, and one for mayor.

after losing the case, Virginia Beach officials proposed a settlement where voters would cast ballots in three superwards, plus within single districts and for an at-large mayor

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Potential Changes to City’s Election System (May 11, 2021)

The option of electing all 11 members in a city-wide race was eliminated when the 2021 Virginia General Assembly passed a series of voting-related bills. The legislature responded strongly to efforts in other states, after the 2020 election, to increase restrictions and suppress voting. HB 2198 stated:14

Two other bills, HB 1890 and SB 1395, were described as the Virginia Voting Rights Act. They incorporated provisions similar to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That bill ensured that starting in 2022, Virginia would protect minority groups from voting discrimination techniques even if judges gutted provisions of that Federal law. Any attempt by Virginia Beach to eliminate its seven voting districts and create a Zero-Eleven (0-11) system, with all members elected citywide, was expected to result in a state court ruling that the proposal illegally diluted the influence of minority voters.15

To correct the violation of the Voting Rights Act, as determined in 2021, Judge Jackson ordered both parties to submit plans that would remedy the problem. The judge chose an independent expert, a political science professor at the University of California at Irvine named Bernard Grofman, as the Special Master to evaluate the plans.

The judge had not accepted any proposal to draw new boundaries for local elections when the member on City Council from the Kempsville District resigned in early July, 2021. The City Council sought to hold a special election for a new member in November, 2021. A local television station emphasized the problem with using the process adopted in 1996 in the headline of its news story:16

Judge Jackson rejected the city's request to authorize one last election under the old process, but the court did not decide on a new process with district boundaries that would meet state and Federal requirements in time for a November, 2021 special election. As a result, no special election was held for the Kempsville District replacement.

The Virginia Beach City Council ended up having to appoint a new member for that district, choosing a former state delegate to complete the last year of that term. Voters in the Kempsville District had to wait until the 2022 election cycle to identify their preference for who should represent them.17

The settlement proposal from the city to create a 7-3-1 system with three superwards was rejected. The Federal judge chose the 10-1 system with 10 voting districts, plus a mayor elected at-large.

In late December, 2021, U.S. District Judge Raymond Jackson released a new voting district map with 10 election districts, with district boundaries drafted by Special Master Bernard Grofman. At that time, Grofman also was one of two redistricting specialists chosen by the Supreme Court of Virginia to draft new redistricting maps after the 2020 Census. Those two special masters had been appointed after the Virginia Redistricting Commission failed to approve any post-2020 Census redistricting maps for the US House of Representatives, State Senate, and House of Delegates districts.

In Virginia Beach, there were 2022 elections scheduled for six of the 10 City Council seats. Judge Jackson's decision required that the 46,000 residents in each of the six districts with 2022 elections would vote for just one member of City Council.

The new boundaries were drawn by Special Master Bernard Grofman to protect most of the 10 incumbents on City Council; only two were placed in the same district. Incumbents lived in each of the five districts that were not scheduled for election until 2024. Those incumbents remained qualified to serve on City Council, and they met the residency requirement even after redistricting. The mayor, who was not up for re-election until 2024, already could live in any district.

The decision by U.S. District Judge Raymond Jackson did not address elections for the School Board, but the charter for Virginia Beach required School Board elections to follow the same manner and schedule as City Council elections. The School Board decided in early 2022 that future elections would use the new district boundaries and require residency within them, with the 11th member elected at-large just like the city's mayor.

The 2022 School Board election was more complicated than the City Council election. Bernard Grofman's redistricting maps resulted in four School Board incumbents living in District 9. Two districts, District 5 and District 7, had no resident serving on the School Board.

In District 9, one member was serving a term that ended in 2022; the other three had been elected to terms ending in 2024. District 9 was not scheduled for another election until 2024. The one member whose term was expiring had the choice of not running for re-election and leaving the School Board at the end of 2022, or moving to one of the six districts where an election was scheduled and running there in 2022.

The two districts with no incumbent were not scheduled for a School Board election until November 2024. Unless a member of the School Board resigned early, those districts would have no representation for nearly three years while one district had four representatives in 2022 and three in 2023-24. State law prohibited terminating early the terms of the elected School Board members, which would have created vacancies and enabled elections in District 5 and District 7.18

Under Professor Grofman's map, the Oceanfront area with most hotels and resort facilities was divided between District 5 and District 6. In three of the 10 districts, people from racial and ethnic minorities formed a majority of the voters. They gained a greater opportunity to elect a non-white member of City Council, because in a 10-1 single member district system the citywide white majority would not be a factor except in electing the mayor.

When adopting the new 10-1 map, Judge Jackson wrote:19

Virginia Beach was forced by a 2021 Federal Court decision to adopt 10 separate election districts for City Council and School Board elections

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Virginia Beach Local Election Districts

In a 6-4 vote, the City Council chose to apppeal Judge Jackson's ruling. If the city lost the appeal, it would be obliged to pay the legal fees of the plaintiffs who had won the case in Judge Jackson's court. They claimed they were owed $3.6 million. Virginia Beach officials rejected an offer by the plaintiffs to accept $1.6 million and settle the case. The appeal argued that the non-white residents did not vote as a bloc:20

Virginia Beach won the appeal, successfully overturning Judge Jackson's decision. The legal fees for the appeal cost $400,000, but winning limited the risk of having to pay $3.6 million in legal fees to the plaintiffs.

The Fourth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals determined on July 27, 2022 that the General Assembly had already passed a law requiring the city to establish 10 single-member districts before Judge Jackson had ruled, so the case was moot. That allowed the appeals court to avoid deciding if the District Court judge had been correct and the 7-3-1 system violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act.21

In the 2022 election, two incumbents were defeated. That election created the most diverse City Council in Virginia Beach history; four African Americans won seats on the 11-member council.22

new voting districts established by a Federal judge at the end of 2021 split the Oceanfront into District 5 and District 6

Source: Eastern District Court of Virginia, Holloway v. City of Virginia Beach

Winning the appeal created the opportunity for City Council to ask the General Assembly to authorize at-large seats again. Such authorization would create the risk that a future Federal judge would rule, like Judge Jackson, that at-large districts in Virginia Beach illegally diluted the minority vote and violated the 1965 law.

In 2023, the new City Council elected under the 10-1 system rejected trying to return to the old system. City Council formally adopted the 10-1 redistricting plan, with no at-large voting except for electing the major.

At the start of 2024, a special election was held in District 1 because the incumbent had resigned to become the Sheriff. Only residents in District 1 could vote for their member of City Council.

The next step was for the General Assembly to modify the city's charter, because the old charter issued by the legislature to establish the independent city in 1964 reflected concerns about the merger with Princess Anne County and still required three seats to be chosen in at-large districts. Before the 2024 session of the General Assembly, the Virginia Beach City Council officially requested that the charter be changed to authorize the 10-1 system. As requested, the General Assembly revised the charter in the 2024 session to align it with the court decision and establish that City Council members would be elected in 10 separate districts and the mayor would be elected at large.

However, Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed the 2024 bill, after the legislature rejected his proposed amendment to make the change effective only if the 2025 session of the General Assembly reenacted the bill. Youngkin justified the veto by citing a lawsuit filed by city residents. They were asking a state judge to say the charter required having seven single-member districts and three at-large districts with a mayor elected at-large, and that the city must comply with the charter requirements in its elections.

The plaintiffs failed to obtain an injunction from a state judge to require the 2024 City Council election be based on the old 7-3-1 system as required by the city charter. The judge did authorize the suit to continue. Plaintiffs had the possibility of winning the case in 2025. If so, that would require drafting new post-2020 Census maps to define the boundaries of seven single-member districts and three at-large districts.23

As City Council prepared its 2025 legislative agenda in October, 2024, the lawsuit was still in process. City Council was prepared to renew its request to revise the charter and establish 10 single-member districts, but the influential business community remained opposed. The Virginia Beach Hotel Association, Virginia Beach Restaurant Association and Atlantic Avenue Association advocated for the City Council to support General Assembly authorization of three or four at-large seats plus a mayor elected at-large.

State Sen. Aaron Rouse, who had served on City Council in Virginia Beach, was blunt in his assessment that key business owners wanted excessive representation on City Council:24

A majority of the members on City Council voted on November 12, 2024 to include in the legislative agenda a request for the General Assembly to modify the city charter. Action by the state legislature to authorize the 10-1 system of representation would bring to a close efforts to re-establish multi-member districts. However, amendments to the city's charter required a 75% approval majority, and the 7-4 vote fell two votes short of that threshold.

Three incumbents on City Council who had voted for that legislative agenda item in 2023, and had just been re-elected in 2024, switched their votes and opposed the charter change. Mayor Bobby Dyer, who was one of the three, said:25

Even though City Council remained divided on requesting a change in the city charter, some members from the region in the 2025 General Assembly proposed mandating the 10-1 voting district system. The request for action by the state legislature to eliminate the potential for future at-large elections, except for mayor, failed in the State Senate. The final vote was 21-19, split along partisan lines. Though 21 Democrats supported the bill, charter changes require a supermajority of 27 votes in the State Senate.

The lawsuit challenging the redistricting in 2023 was still in process, and the Attorney General stated that the city was not obliged to alter its charter to match the Federal court order issued in 2021 by U.S. District Judge Raymond Jackson.

A state senator from Virginia Beach identified the key factor causing the General Assembly to avoid action:26

On May 6, 2025, the City Council authorized asking the Circuit Court to put a referendum on the November 2025 ballot. If city voters supported the 10-1 system, in which all but the mayor ran in separate single-member districts, then the redistricting debate would end and no further action would be required.

If the voters supported returning to something like the previous 7-3-1 system, then Virginia Beach representatives in the General Assembly would be expected to request a change in the city charter. The change would be required to authorize electing some City Council members as well as the mayor at-large.27

On June 16, 2025, Judge Jackson rescinded his ruling in the Holloway v. City of Virginia Beach case. That authorized the plaintiffs to bring a new challenge to the multimember district system, but created the opportunity for the voters to determine their preference before another Federal ruling on whether the 7-3-1 system violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

A Circuit Court judge ruled later in June, 2025 that the City Council lacked authority to bypass the charter and create the 10-1 voting system. The judge decided that action on his decision should wait until after the November referendum, when city voters would determine if they wanted to adopt the 10-1 system. Federal and state courts had both decided that the imposition of the 10-1 system, inconsistent with the city charter, required the General Assembly rather than the just the courts to revise the city charter. Both levels of courts decided that the referendum should be held before further legal action.

If voters supported the 10-1 system, then the General Assembly was expected in 2026 to modify the city charter. If voters rejected the 10-1 system, then the city would have the legal authority to return to the 7-3-1 voting system - but potentially face a renewed legal challenge claiming that multimember districts violated the Voting Rights Act.28

One local advocate for retaining the 7-3-1 system noted:29

On November 4, 2025, voters endorsed changing the city charter to use single-member districts for City Council elections. By a 53-47% majority, city residents voted "yes" on this referendum question:30

Two weeks after the election, the Virginia Beach City Council voted unanimously to request that the General Assembly modify the city charter and establish the 10-1 voting system.31