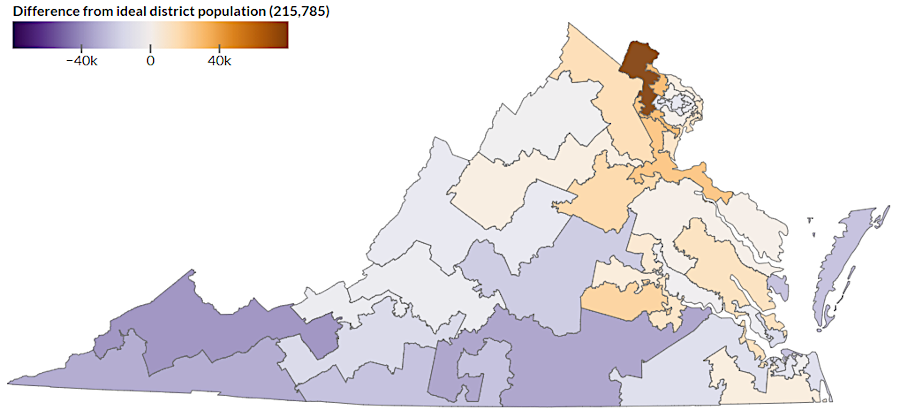

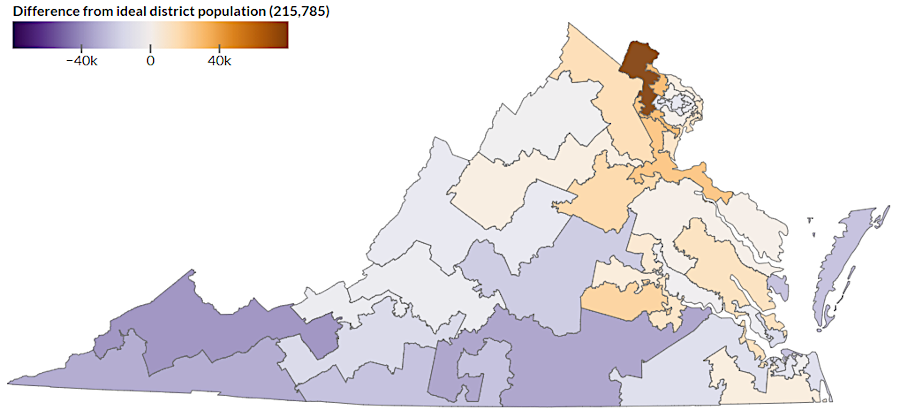

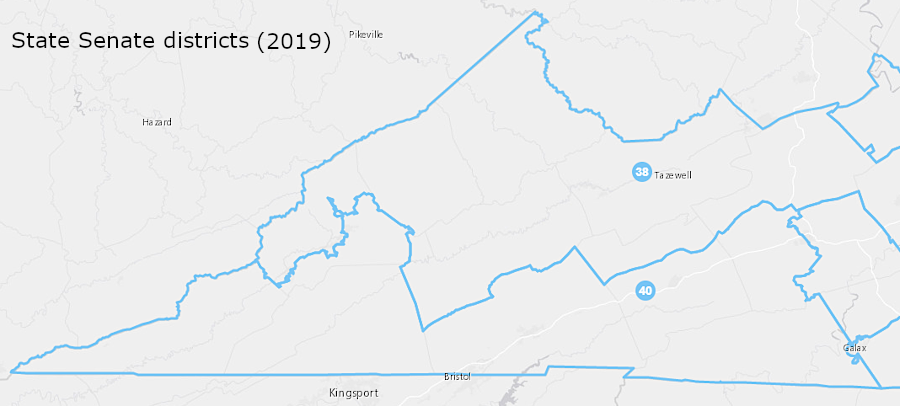

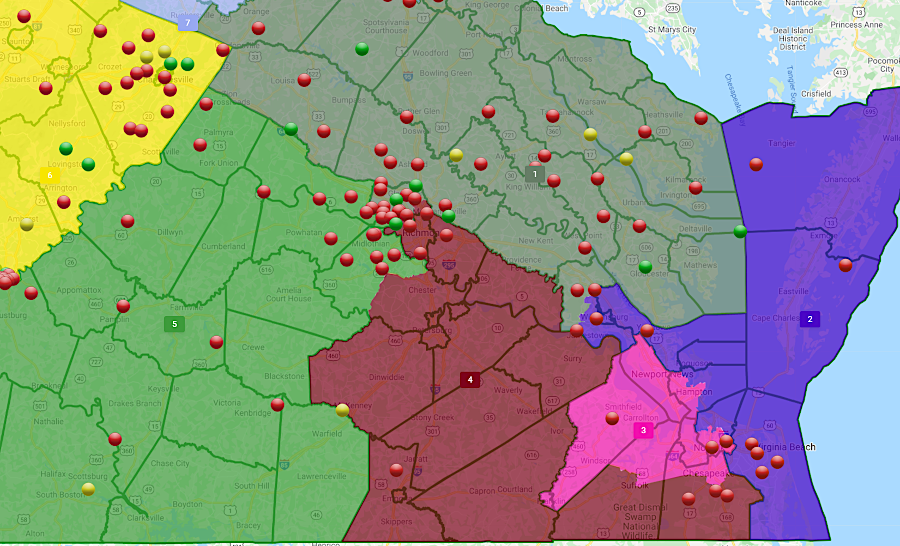

40 State Senate district boundaries established in 2011 had to be readjusted to reflect population changes between 2010-2021

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Gainers, Losers in Redistricting

40 State Senate district boundaries established in 2011 had to be readjusted to reflect population changes between 2010-2021

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Gainers, Losers in Redistricting

Redistricting was required after the 2020 Census so US Congressional districts would be essentially equal to each other in population, meeting the US Supreme Court requirement for "one-person, one-vote." The requirement for Federal election districts was stricter than for state election districts, but Virginia districts had to be "substantially" equal in population.

The 2021 redistricting process was unique. For the first time, the General Assembly had to share responsibility for drawing new voting districts after the decennial census with a group of citizens. The voters had passed a constitutional amendment in 2020 that created a 16-person Virginia Redistricting Commission to propose new boundaries.

As one scholar at William and Mary Law School noted:1

The commission was designed to be bi-partisan, not non-partisan. The elected legislators structured the commission to maintain a measure of control over the process, resisted efforts by OneVirginia2021 and other anti-gerrymandering groups to eliminate the ability of the politicians to choose their voters by "packing" and "cracking" communities of interest when drawing election district boundaries.

Half of the commission's 16 members were chosen by the General Assembly. The House of Delegates selected two Republicans and two Democrats, as did the State Senate. The legislators chosen for the 2021 commission were:

Del. Les Adams (R - Chatham)

Sen. George Barker (D - Fairfax)

Sen. Mamie Locke (D - Hampton)

Sen. Ryan McDougle (R - Hanover)

Del. Delores McQuinn (D - Richmond)

Sen. Steve Newman (R - Lynchburg)

Del. Margaret Ransone (R - Westmoreland)

Del. Marcus Simon (D - Fairfax)

Three of the four members from the State Senate had to approve the new boundaries for State Senate districts, and three of the four members from the House of Delegates had to approve the new boundaries for House districts. Two members from one party could vote against a draft map that was perceived as too partisan against their party, blocking the proposal from moving forward.

One of those chosen to represent the General Assembly was State Senator George Barker. He had been the lead Democrat in 2010 for that party's redistricting of the State Senate, when Republicans in control of the House of Delegates gerrymandered those 100 districts and Democrats in control of the State Senate gerrymandered those 40 districts. The Democratic gerrymander was not successful; Republicans gained two State Senate seats in the 2011 election. The 2011 results created a 20-20 tie, and Democrats were forced to cede control of the State Senate in a power-sharing arrangement.

A panel of retired judges chose another eight citizens for the Virginia Redistricting Commission. Since the legislature had elected ll of the judges, their partisan leanings would be a factor. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia presented a list of retired Circuit Court judges to the party leaders in the General Assembly. Those leaders chose four judges, and the four judges chose a fifth from the same list.

The five judges were required to choose the eight citizen members of the Virginia Redistricting Commission from lists prepared by the party leaders in the House of Delegates and State Senate. The judges did not have the option of choosing eight non-partisan citizen members based on their own preferences; they had to choose from lists submitted by four partisan leaders. The judges had to select two people from four separate slates, one each submitted by the Speaker of the House, the House minority leader, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate and the Senate minority leader:2

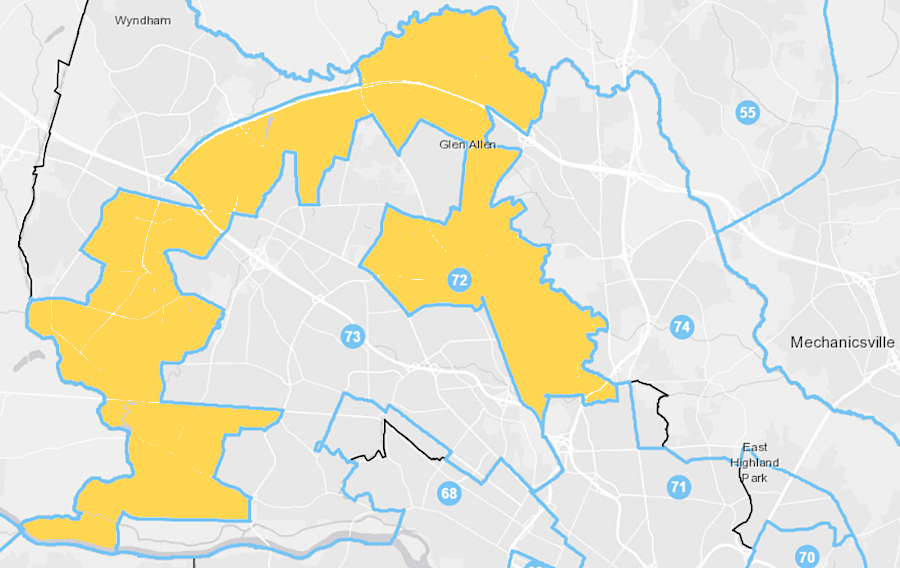

House of Delegates District 72, as drawn in 2011 redistricting, resembled a horseshoe or toilet bowl and was a classic example of boundaries that were not "compact and contiguous"

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, House (HB5005 Passed 4/28/11)

Over 1,200 people submitted applications to those four partisan leaders, seeking to be included in one of the four lists submitted to the retired judges. The leaders of the two parties in the legislature nominated 62 people from that pool. The five retired judges consciously tried to select a diverse group of panelists.

Creating the commission limited the traditional ability of the party in power to gerrymander election districts to increase the electability of their candidates. Gerrymandering was also used to constrain the potential election of candidates from the other party, and to force incumbents into running against each other in one district. The Republican legislators consistently supported creation of the Virginia Redistricting Commission in 2019 and 2020, as did the Democrats in the State Senate.

The constitutional amendment to create the Virginia Redistricting Commission was passed by two sessions of the General Assembly, in 2019 and 2020, before being approved by the voters in November 2020. In 2019, when the Republican Party controlled the General Assembly and it was unclear who might win a majority in the elections later that year, the delegates had voted 83-15 in favor of putting the redistricting commission proposal on the ballot.

Results of the 2019 election caused a dramatic reduction in support among the Democratic members in the House of Delegates. Control of that house shifted after the 2019 election to the Democrats. It became clear that one party could control the 2021 redistricting of both houses of the General Assembly.

In 2020, only nine Democratic Delegates were willing to give up control of the redistricting maps and support a bipartisan commission with citizen members. Just nine Democrats in the House of Delegates joined with 45 Republicans to endorse the ballot measure, which passed in a 54-46 vote.

One observer commented:3

The advocates for a nonpartisan commission had to compromise to get a process not controlled by incumbent politicians. As one noted:4

The political switch among Democrats in the House of Delegates between 2019-2020 reflected the traditional desire to craft partisan maps. As one experienced observer noted when the redistricting commission started to meet:5

The commission faced the challenge of revising boundaries to ensure an equal number of people lived in each district, for elections to state and Federal offices. That one person-one vote requirement also applied to revising districts for city council and county supervisor seats, where cities had defined wards and counties had defined magisterial districts. However, the Virginia Redistricting Commission had no responsibility for local districts, and local officials were free to gerrymander as in the past.

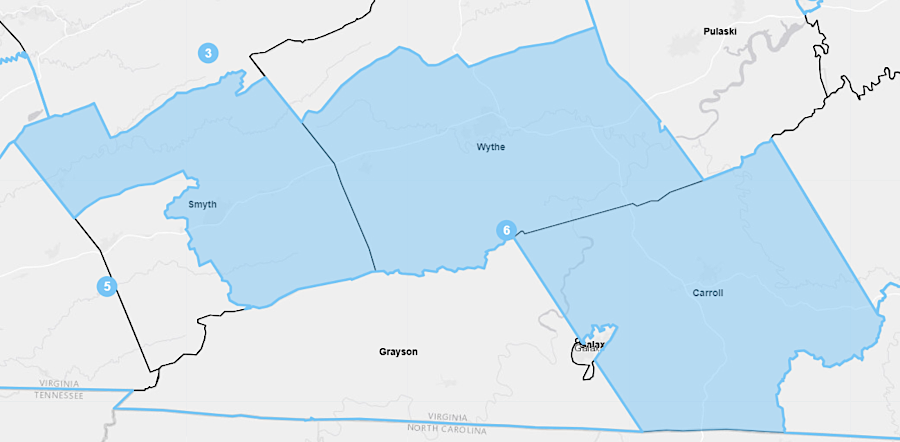

In advance of redistricting, it was clear that Republicans in Southside and Southwestern Virginia would be affected. Slow population growth in those regions, compared to Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, would require drawing larger boundaries. Even if voters approved the redistricting commission, some Republican incumbents in rural Virginia would end up having to run against another Republican incumbent.

To avoid that challenge, in 2019 Del. Todd Pillion decided to run for the 40th District in the State Senate. He had not been challenged by another candidate in his last two elections to the House of Delegates, but his election to the State Senate in 2019 guaranteed he would be in office through 2023 no matter how redistricting affected Southwest Virginia.6

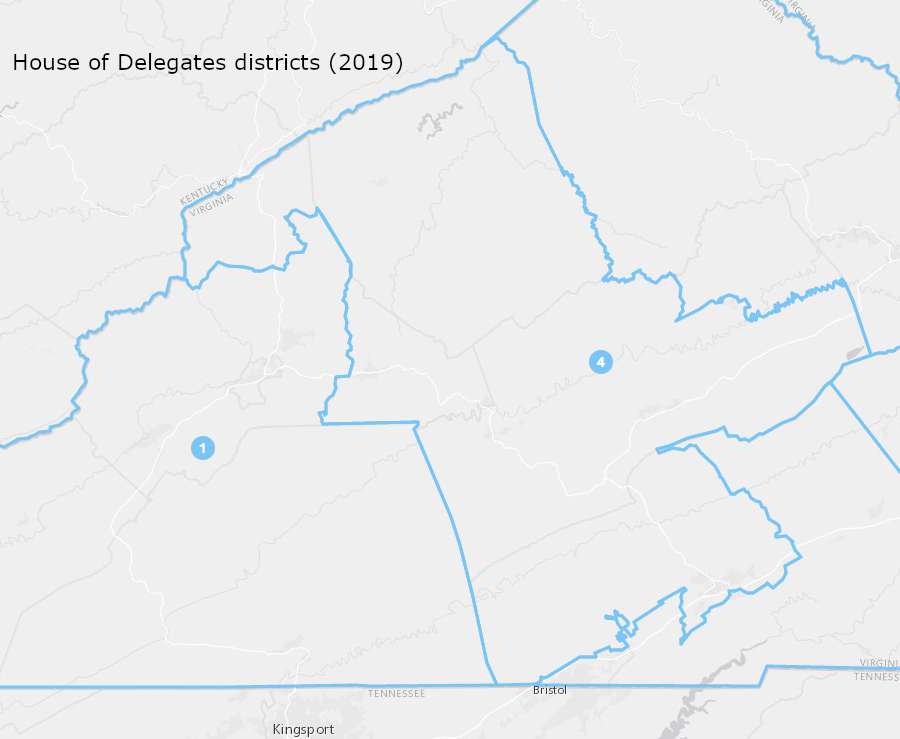

in 2019, Del. Todd Pillion chose to run for a four-year term in State Senate District 40 rather than for re-election to a two-year term in House of Delegates District 4

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Virginia Redistricting Commission

The timelines for action by the redistricting commission were tight. It was required to propose new district boundaries for the State Senate and the House of Delegates of the General Assembly within 45 days after the Census Bureau released final population numbers for Virginia. Boundaries for the US House of Representatives districts had to be drawn within 60 days. The deadline for both maps was July 1, unless the Census Bureau's delivery of population data was delayed.

The Census Bureau did delay. It failed to complete the state population counts for apportionment of US House of Representatives seats by the statutory deadline of December 31, 2020. Delays in "counting every American once, only once, and in the right place" were caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. That limited the ability of enumerators to contact nonresponding households, and to resolve duplicate counts for people living in group quarters such as college dormitories but also at alternative residences. There was political interference in the process, including a failed effort to distinguish between residents vs. legal citizens in the Census numbers.

The Census Bureau announced at the end of January, 2021 that apportionment data for drawing new districts within the states would not be available until July, or even later. That created the possibility that the 2021 elections would be held using the same boundaries as in 2019, but terms would be limited to just one year with new elections required in 2022. That approach had been used in 1981, when there were elections for the 100 House of Delegates seats in 1981, 1982, and 1983 (finally for a two-year term).7

The redistricting commission has to complete its work in time for the political parties to hold primaries, select candidates, and campaign before November elections. There was a risk that the commission would end up in deadlock, since the constitutional amendment creating it required approval by 75% of the delegates and 75% of the state senators but each political party appointed only 50% of them. Advocates for a completely non-partisan commission were concerned about the risk of backroom bargaining, creating boundaries that protected re-election potential for key politicians or incumbents in districts at risk of having competitive elections.

Partisan officials also highlighted the remaining potential for political bias, noting that even the citizen members selected by retired judges were nominated by political leaders in the General Assembly. Delegate Marcus Simon was appointed to the commission; he had supported creating it in February 2019, when the House of Delegates voted 85-13 to advance SJ 306.

However, Del. Simon became a leading opponent of ratifying the constitutional amendment after Democrats won control of the legislature in the November 2019 elections and his political party gained the power to define the election districts for the next decade of elections. Simon then flipped his opinion and claimed to be concerned about potential partisan influence, when he argued for a "No" vote before the 2020 election:8

The General Assembly rejected the proposal for a non-partisan (vs. bi-partisan) redistricting commission which included no legislators, as originally advocated by OneVirginia2021. Instead, the General Assembly structured the commission so any two delegates or any two state senators could block adoption of new maps.

To adopt any new set of maps for Congressional, State Senate, and House of Delegates districts, 12 of the 16 commissioners had to approve. Within those 12, six of the eight citizens had to approve. In addition, six of the eight legislators also had to approve the maps, including a minimum of three of the four delegates and three of the four state senators. Since Democratic and Republican leaders in the General Assembly each appointed two delegates and two state senators, the potential for the Virginia Redistricting Commission to endorse a overly-partisan redistricting plan was reduced.

There was also the potential for delay by the legislature. Each house of the General Assembly was given an opportunity to reject the redistricting plan submitted by the commission. In that case, the Virginia Redistricting Commission would have to revise its rejected proposal and submit another redistricting plan. If rejected by legislators a second time, then the Supreme Court of Virginia would draw the district boundaries.

The review process at the legislature could consume as much as 14 days for the first review, plus another seven days if a second review was required. In addition, time would be required by the redistricting commission to made adjustments, and for the Supreme Court of Virginia to make a decision.9

On February 12, 2021, the Census Bureau announced that Virginia would not receive the detailed data needed to redistrict boundaries within the state until September 30, 2021. The Federal agency decided that dropping plans to follow staggered delivery dates for redistricting data sped up the total process for all 50 states, though it would disrupt the scheduled legislative elections in New Jersey and Virginia.

The Census Bureau prioritized completing the population data required for the fundamental task of reapportioning membership in the House of Representatives. Population changes had caused Virginia to lose one seat in the House of Representatives after the 1930 Census, and to gain a seat in 1950 and 1990. The 2020 Census did not alter Virginia's total in the House of Representatives, but the delay still left plenty of time for the Virginia Redistricting Commission to the boundaries of the 11 districts to ensure equal population numbers before the 2022 elections to the US House of Representatives.

The September delivery date was six months after the deadline established by law, but members of Congress quickly announced support for changing the deadline and releasing data for all states at the same time in order to ensure accuracy. Prioritizing delivery to Virginia and New Jersey, releasing their data 4-6 weeks ahead of other states because of their 2021 elections, no longer offered any benefits. By February it was clear that the release date would be too late for Virginia to complete redistricting, nominate candidates, and have adequate time for candidates to campaign in new districts before the scheduled November, 2021 elections.10

Delaying the redistricting for 2021 elections violated the state constitution, as amended in 2020. The constitution granted the Virginia Redistricting Commission 45 days to craft new boundaries, with results expected by July 1. If the Census Bureau delivered the population data on September 30, there was no possible way to comply with the constitutional mandate:11

The redistricting amendment to the state constitution, approved in 2020, had little impact on redistricting for local offices. Elected officials retained the power to choose their own voters, and to enhance the potential of incumbents to be reelected. Prince William County established redistricting criteria that defined retention of incumbents as a priority:12

Prior to the 2020 constitutional amendment, state law did require at the local level:13

The amendment did not require the Virginia Redistricting Commission to get involved in any way with redistricting magisterial districts in counties, wards/districts within cities and towns, or school board seats. The Amendment did add one new requirement for local election districts intended to enhance the election of candidate from minority groups. In a majority-minority county such as Prince William, where no ethnic group exceeded 50% of the population, that provision created a new possibility. Advocates could argue for magisterial district boundaries intended to increase the opportunity for electing white candidates to the Board of County Supervisors:14

The 2020 amendment did not require, and the General Assembly has not mandated, that local redistricting meet the "communities of interest" standard which was established for congressional and state legislative districts:15

The 2020 General Assembly modified the requirements for drawing county and city precincts. It required:16

when Virginia drew 2021 election district boundaries, a new srtate law required that people incarcerated in rural prisons (top) be assigned to their last known residential address (bottom)

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), End of "Prison Gerrymandering" Saps Rural Virginia

The legislators were prescient in anticipating that congressional, Senate, and House of Delegates districts might not be adopted by June 15, 2021 after the 2020 census. Local jurisdictions were authorized to draw precinct boundaries based on previous districts for 2021, then revise those boundaries after the district boundaries were completed for US House of Representatives, State Senate, and House of Delegates districts.

The delay in receiving the 2020 Census data made it impossible to revise the House of District boundaries for the House of Delegates races in 2021. The solution was to cut the term of those elected in 2021 in half, to just one year. Delegates elected in 2021 had to run again in 2022, in newly-drawn districts, and would serve only one year again. Those elected in 2023, from the districts established in 2022 after consideration of the Census data, would serve two-year terms.

The delay in redistricting was expected to help the Republican Party capture control of the House of Delegates in 2021. The boundaries for the 100 delegate seats were drawn in 2011, when that party controlled the House of Delegates. Even after court decisions that required some redistricting before 2020, those 2011 boundaries created districts that favored election of Republicans.17

That change did not affect members of the State Senate whose terms ended in 2023, but altered the opportunity for incumbent members of the House of Delegates to seek the nomination of their party for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, or Attorney General in June, and if unsuccessful to run again for re-election to the House of Delegates in an August primary.

Del. Kirk Cox, the Republican Party's Minority Leader, chose to run for his party's nomination for Governor; he did not get on the 2021 ballot as a candidate for the House of Delegates. When he lost, he had no "fall back" opportunity to be elected to another office that year. Del. Haya Alaya declined to run again in the 51st District, and put all her efforts into being nominated as the Democratic Party candidate for Lieutenant Governor.

Some incumbents chose to run simultaneously for both their House of Delegates seat and higher office. Del. Sam Rasoul had no primary challenger in the 11th District, so he was guaranteed to be on the ballot in November even if his effort to be nominated for Lieutenant Governor failed.

Del. Mark Levine, seeking nomination for both Lieutenant Governor and to the 45th District seat in the House of Delegates, advertised he was "A leader so nice, you can vote for him twice!" Del. Lee Carter was on the ballot twice on June 6, seeking nomination as the Democratic Party candidate for governor and for the 50th District seat. Del. Elizabeth Guzman initially announced she would run only for Lieutenant Governor and got on the ballot for that office, while other candidates got on the ballot seeking to replace her as delegate for the 31st District. After realizing her statewide candidacy would not succeed, she dropped her bid for Lieutenant Governor and got on the ballot in time to run for re-election to her House of Delegates seat.

As described by the Washington Post:18

Two of the three incumbents seeking dual offices were defeated in both races, ending at least temporarily their careers are elected officials. Delegate Lee Carter (D-50) lost both the Governor's race and his House of Delegates race. Delegate Mark H. Levine (D-45) lost in both the Lieutenant Governor's race and in his House of Delegates race. Delegate Elizabeth Guzman (D-31) won her 2021 primary and then the general election in November, so she returned to the House of Delegates in 2022 after dropping out of the Lieutenant Governor's race.

Former Delegate Haya Ayala's gamble paid off. After resigning her seat in the 2nd District, she won the Democratic nomination for Lieutenant Governor. Sam Rasoul, who lost his bid for Lieutenant Governor, had no primary opponent. That ensured he would be the Democratic nominee for re-election in the 11th District in November, 2021. Jennifer McClellan was serving a four-year term in the Virginia State Senate which ended in 2023, so after losing the 2021 race for Governor she remained in the General Assembly.19

The redistricting process in 2021 altered the traditional way of counting prisoners when redrawing election district boundaries. The General Assembly required that inmates be assigned to their last known residential address, not to the address of the facility in which they were incarcerated on April 1, 2020 (as counted by the US Census).

The different addresses used for 20,000 people held in federal, state and local institutions changed reduced the political influence of rural areas, where many prisons were located, and increased the population count in more-urban areas where many of the convicts had lived. The Supreme Court of Virginia rejected a challenge to the new way of counting prisoners in the 2021 redistricting process.20

To cope with the delay in delivery of new Census data, some states started their redistricting process by using American Community Survey data. In Illinois, Democrats who controlled the legislature drew new maps prior to a June 30 deadline. Delay past that deadline would have made a bipartisan commission responsible for that state's redistricting, increasing the opportunity for Republicans to win elections. Oklahoma's legislature did the same, though in that case the Republicans raced to complete redistricting to their advantage before a deadline that would transfer the process to a bipartisan commission.

In Colorado, the independent redistricting commission used the American Community Survey to draw draft maps for public comment. The deadline for that commission was tied to the date the Census Bureau released the data, but it chose not to wait. The release of draft maps in June, 2021 stimulated public review and comment, which could be incorporated into the final maps to be completed after the Census Bureau provided the official 2021 data.21

An appointee to the redistricting commission, Marvin Gilliam, resigned in July, 2021. He had been nominated by Senate Minority Leader Tommy Norment, and happened to be the only member from west of the Blue Ridge. Though the initial eight citizen members had been appointed by the panel of judges, the redistricting committee chose his replacement to fill the vacancy. The procedures for his replacement required that at least one of the eight Democrats had to vote in favor of a new Republican member. In the end, the appointment was made by a 13-1 vote.21

A person from the Lynchburg area was selected as the replacement. That left Southwest Virginia without any representative on the Virginia Redistricting Commission. Though one member of the commission noted that the appointment was "as close as we kind of get to Southwest, the Roanoke Times questioned if the lack of geographical diversity met the requirement to "give consideration to the racial, ethnic, geographic, and gender diversity of the Commonwealth."

The paper editorialized:22

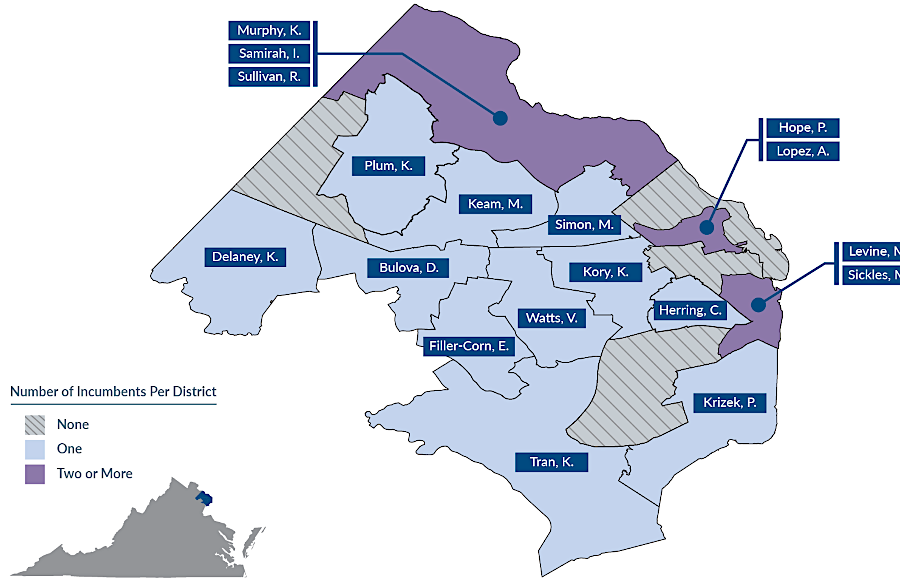

Prior to the release of the detailed Census data, differences of opinion became clear between legislators and non-legislators on the redistricting commission. In the initial discussions, the legislators appeared more concerned about incumbency than partisanship. In October 2020, the General Assembly's Joint Reapportionment Committee had required that the redistricting commission be provided the home addresses of the current members of the legislature. That address data would allow the commission to draw district boundaries that avoided placing incumbents in the same district, or to use a partisan perspective and purposely place incumbents in the same district to reduce the chances of one getting re-elected.

The General Assembly did make clear that boundaries of existing legislative districts did not qualify as a "community of interest." Even if a legislator had served one area for the last decade or two, the commission should not define the legislative district boundaries as a community of interest to be protected - but the General Assembly ensured the commission could still consider the addresses of incumbents for political reasons. A briefing to the commission by a Division of Legislative Services attorney included:23

In 2010, California voters had established an independent redistricting commission and prohibited it from considering the addresses of incumbents when drawing new boundaries. As described by political pundit Larry Sabato at the University of Virginia, the commission took a "wrecking ball" to the old district boundaries for state legislators. It drew a new map after the 2010 Census that provided little protection to incumbents:24

In 2021, the eight legislators on the Virginia Redistricting Commission appeared more concerned than the non-legislators about splitting the process so House of Delegates members were not responsible for drawing State Senate district boundaries, and vice-versa. The legislators proposed creating two subcommittees, one for House of Delegates redistricting and one for State Senate redistricting. Two committees would avoid having members of one house shape boundaries for members of the other house. In 2011, when Republicans controlled the House of Delegates and Democrats controlled the State Senate, the members of the two houses had worked independently to redraw their boundaries.

The bi-partisan co-chairs, both citizen members, recommended having members of each house on each subcommittee. The legislators refused and the commission was unable to get a majority vote for any subcommittee option, so no subcommittees were created.

The commission members also debated whether to start from scratch to define new district boundaries as done by California's commission after 2010. The alternative was to start with the boundaries of existing districts and make modifications. Changes might improve the compact and contiguous character of a district, and facilitate the preservation of communities of interest. Starting with existing boundaries could minimize the number of incumbents who might be forced to move, or to run in a new district with voters who had not supported them in the past.

Experienced incumbents argued that the expertise accumulated over years of service were essential to effective government. The members of the General Assembly were part-time legislators paid just $18,000/year to make decisions on over a thousand bills in a six-eight week session. The legislators lacked the staff and time to understand the complicated budget and potential impacts of transportation, education, energy, and other key issues in their initial years, but gained perspective with experience. The legislators with decades of service should be considered as essential resources, not vilified as "career politicians."

The lawyers hired to represent Democratic and Republican perspectives advocated for modifying existing boundaries to retain incumbents. In response, one of the non-legislator members commented to the State Senator who led the redistricting for the 40 State Senate districts in 2011:25

The Bureau of Census released its detailed data on August 12, missing the schedule release date by ahead of its self-imposed September 30 deadline. Virginia Redistricting Commission chose to use August 26 as the start date for its 45-day map-drawing window, aligning the time to reflect the date when the Census data would be available in a more-useful format. That set the deadline for proposing 140 General Assembly district maps by October 10, and 11 maps for US House of Representative districts by October 25.

News stories about the redistricting process highlighted how the members of the commission were struggling to reach across the political divide, with headlines such as "Partisan tension roils Virginia redistricting commission" and "Virginia Redistricting Committee Opts for Partisan Approach to Map-Drawing."

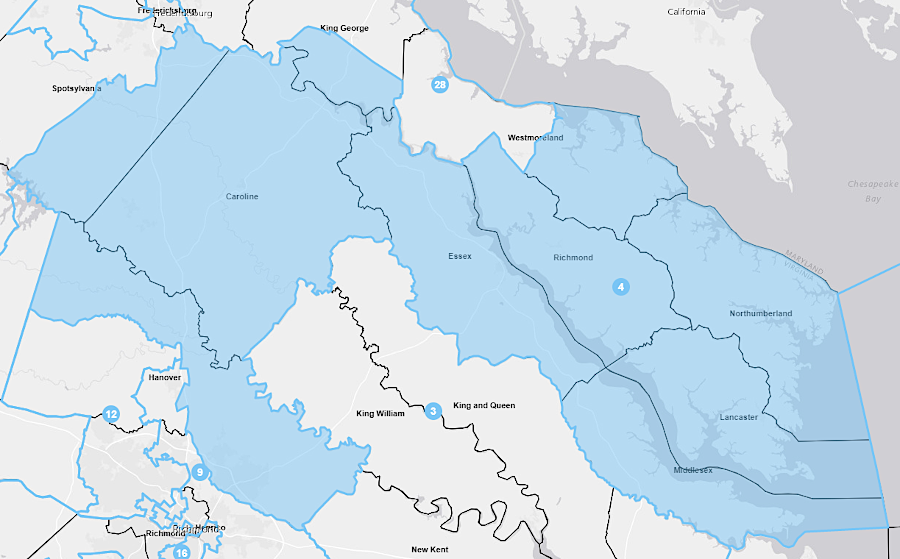

The members did manage to agree on a 9-6 vote to consider the residence of incumbent legislators when drawing new boundaries. In a 12-4 vote, it decided to minimize how jurisdictions were split into different districts. Sponsor of that motion was Sen. Ryan McDougle, whose State Senate District 4 included parts of 10 separate jurisdictions. They also acknowledged that they would consider political voting trends when crafting new maps, rather than wait until maps were drafted and then review the political impacts. One opponent of that decision described it as "rigging the process from the beginning."

State Senate District 4, represented by Ryan McDougle in 2021, stretched across all or part of 10 jurisdictions

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Current Senate (HB5005 Passed 4/28/11)

One of the conflicts was whether the Virginia Redistricting Commission should hire two teams of partisan map-makers, comparable to its two teams of Republican and Democratic lawyers. The other option was to hire a non-partisan organization, such as the Spatial Analysis Lab at the University of Richmond. One Republican member claimed that finding a neutral mapmaker with experience in redistricting would be equivalent to finding a unicorn.

After release of the Census data, the commission deadlocked on the decision. All eight Democrats voted for a single map drawer and all eight Republicans were opposed, so the motion failed on a tie vote. That left the partisan lawyer teams free to hire separate mapping specialists to draft boundaries for the 2022-2030 elections.

Several of the citizen members were frustrated by the partisan angles and decisions to "split the baby constantly along party lines." One commented:26

One of the members appointed by the General Assembly noted more optimistically:27

That comment reflected the narrow focus of elected officials to balance Republican and Democratic party interests, being bipartisan rather than nonpartisan. Citizen members appeared less interested in creating district boundaries that would be "safe Republican" or "leans Democratic," and more willing to consider districts that blended voters of both parties and created greater opportunity for flipping seats.

A "hot mike" exchange, when two commission members did not realize their conversation was being broadcast, was revealing. Brandon Hutchins, a citizen member representing Democrats, was speaking with State Senator George Barker. He led the process in 2011 to create partisan redistricting maps for the State Senate. As reported by the Virginia Mercury, Hutchins expressed concerns to Barker that citizen reaction to a process that prioritized political considerations of Democratic and Republican leaders would be negative:28

The director of the National Black Nonpartisan Redistricting Commission made clear his expectation that the divided commission, unable to agree on a single set of lawyers or mapmakers, would be unable to agree on maps either. His aid in frustration:29

In a surprise to some observers, the Virginia Redistricting Commission decided by a 9-7 vote to create new boundaries from scratch, without a parallel effort to draw boundaries also based on existing districts. The alternative was to adjust existing district boundaries, starting with boundaries that were comfortable to most incumbents and then adding/subtracting precincts to meet the required population numbers.

Starting from scratch prioritized creation of compact and contiguous districts that represented communities of interest. Such an approach increased the potential of putting multiple incumbents into one district, and creating other districts with no incumbent.30

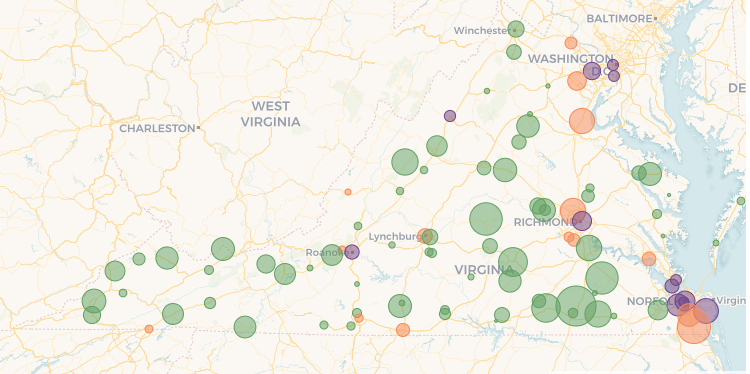

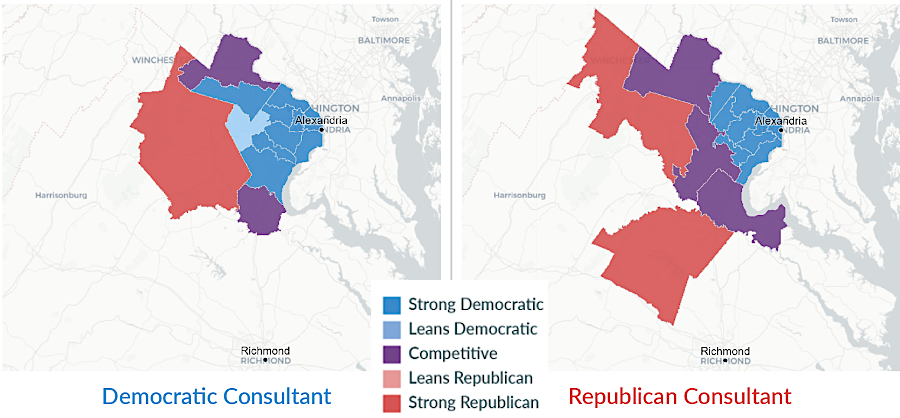

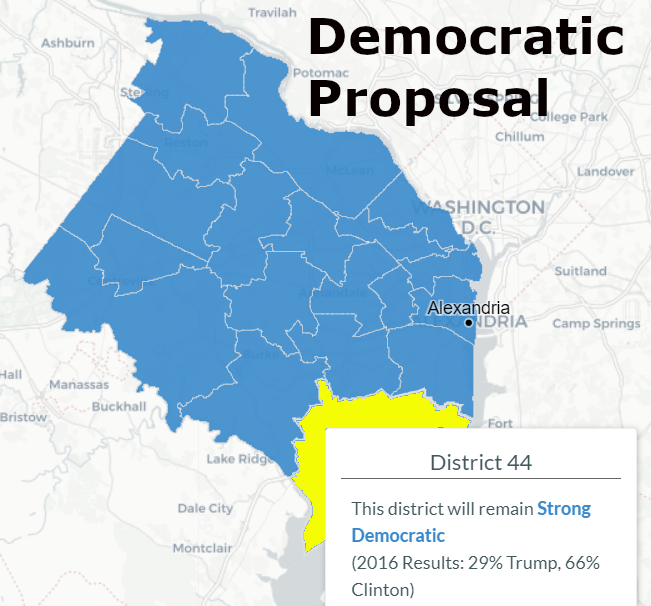

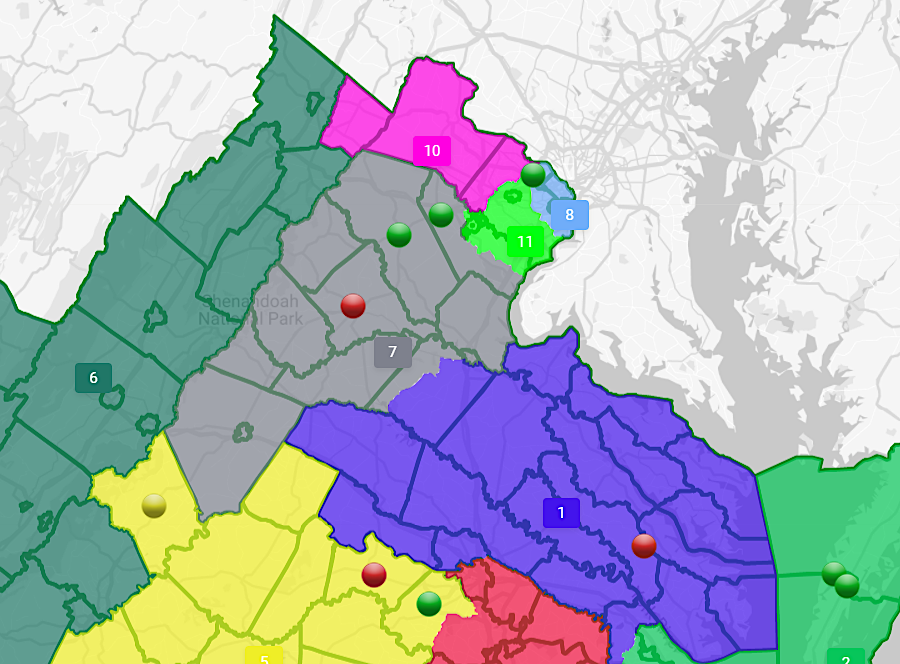

The first draft maps were prepared for Northern Virginia, with seven other regions to be mapped later. No matter how the district boundaries were drawn, there would be relatively little partisan advantage because the area was so heavily Democratic. Most districts would remain tilted towards election of Democrats, but the Republican lawyers managed to draw boundaries of "compact" and "contiguous" territory would be more competitive. than the Democratic proposal.

Republican lawyers drafted maps that created more-competitive State Senate districts than the proposal from Democratic lawyers

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Partisan Consultant Drawing Maps

proposed redistricting by Democratic and Republican lawyers still left all Northern Virginia House of Delegates districts as strongly tilted towards Democratic candidates

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Proposal B1 for Northern Virginia, presented by the Redistricting Commission's Democratic map drawers on September 2, 2021

The draft prepared by the Democratic lawyers ignored the home addresses of incumbents, and the elected officials on the Virginia Redistricting Commission were not happy with the proposal. Delegate Marcus Simon commented that he liked the Republican proposal better, since it left more of his existing district intact. The draft map placed State Senator Barker and State Senator Chap Petersen in the same district. Barker warned that the General Assembly had to approve the final map, and not protecting incumbents might result in rejection.31

Republican lawyers proposed new House of Delegates districts in Northern Virginia that would place three incumbents within one district

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Without Regard to Incumbency

Right after the Census data was delivered and the first maps were drafted, one of the commission members was infected with COVID-19 and meetings were paused. Then, as the work of defining new election district boundaries was getting intense, State Senator Steve Newman resigned from the Virginia Redistricting Commission.

One observer noted that Sen. Newman may have been frustrated because the commission co-chairs had "dropped a bomb" at the August 23 meeting. They adopted a protocol, without a commission vote, that banned commission members from communicating with the attorneys and map drawers except in a public meeting. The intent was to increase transparency and to minimize citizen concerns about maps being prepared in secret. Sen. Newman had objected strongly, even though he said he was not planning to run for re-election and thus would not be impacted personally. The co-chairs refused to modify their protocol.

The resignation, with 37 days remaining before the deadline to finalize maps for the Virginia House and Senate, forced the Senate Minority Leader to appoint a replacement to step in for the final six weeks of the redistricting process. State Senator Bill Stanley from Franklin County was appointed, adding some geographic diversity.32

After drafting a map that lumped Delegate Marcus Simon with another incumbent, the Democratic lawyers revised their proposal to provide him a district without an incumbent competitor. The consultant used an independent website to get data on the addresses of incumbents; the commission had not provided that information to the map drawers. Del. Simon claimed he had made no request for a change.

State Senator George Barker made an overt effort to amend the map submitted by the Republican lawyers. He proposed a new map that would shift a few precincts so his home would not be within the same district as State Senator Chap Petersen. Barker complained that most of that proposed district was already represented by Petersen, so Barker would be at a disadvantage when trying to win the Democratic nomination in 2023:33

The residence of incumbents could end up being a significant factor when assessing if the proposed statewide map created an unfair impact on one political party. It was possible that the final 100 House of Delegates districts or 40 State Senate districts would create boundaries where many incumbents of one party were forced to run against each other for renomination, while few incumbents of another party were consolidated into common districts.

One of State Senator Bill Stanley's first comments was:34

In mid-September, the commission abandoned the idea of producing maps for different regions and then integrating them. The co-chairs decided there would not be adequate time for that process, and the impacts would be easier to evaluate if statewide maps were considered.35

Protecting incumbents ended up being part of the process. In late September, the addresses of all incumbents were released to the Republican and Democratic map drawers. That enabled drawing maps that had "political fairness," but that particular criterion was given lowest priority. Drawing boundaries to maximize the potential of individual incumbent politicians to win re-election in the next election was seen as a separate issue than partisan gerrymandering, in which boundaries would be drawn to maximize one political party's success for the next decade.

The Republican and Democratic map drawers modified their draft boundaries to alter precincts near the edges of districts, in order to minimize the number of districts in which two or three incumbents would be placed. One experienced reviewer of the redistricting process noted the changes in the October 3 draft maps:36

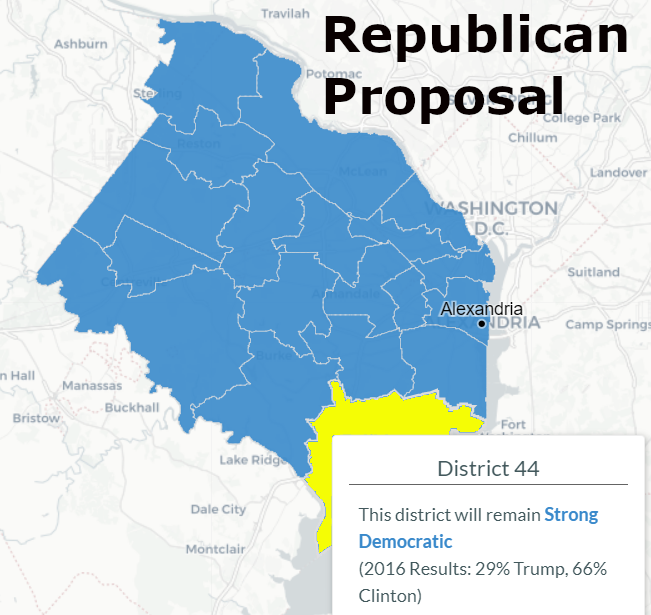

The Republican and Democratic consultants partnered to avoid partisan deadlock on the map of 40 State Senate districts. They proposed a revised map that both sides endorsed, and which would minimize the number of incumbent State Senators who would be placed in the same district.

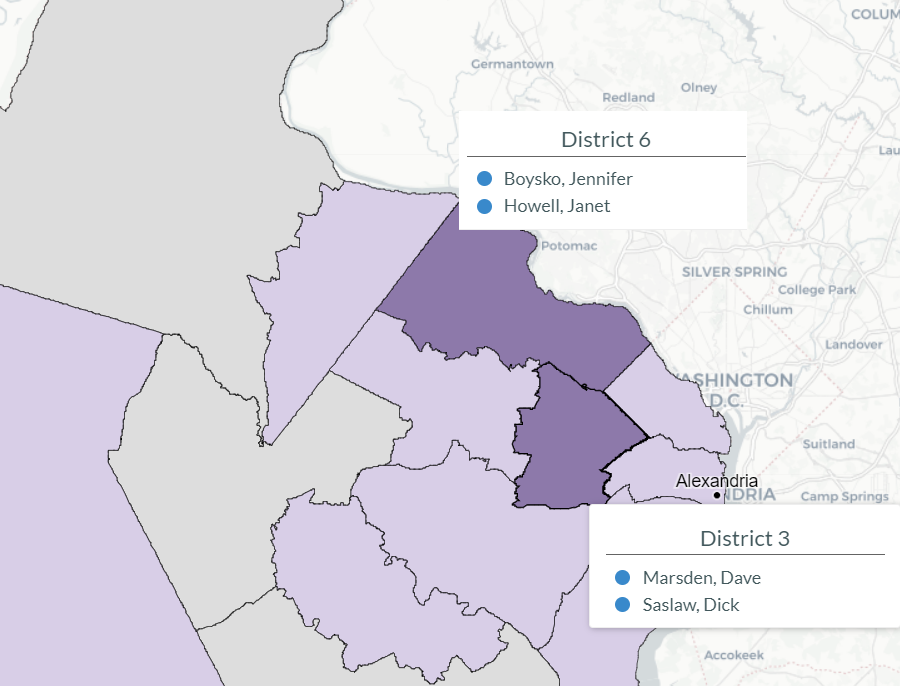

The "tweaked" map had only two districts in Northern Virginia that included the homes of two incumbents. In both cases, one of them was expected to retire rather than compete in a primary for re-election. The two incumbents predicted to retire were senior leaders in the State Senate - Dick Saslaw, the Senate Majority Leader, and Janet Howell, the chair of the Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee.

two proposed State Senate Districts in Northern Virginia (dark purple) included two incumbents, while other districts (grey) had no incumbent

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Commission - Statewide - C2

Near Lynchburg, two Republican State Senators were also placed in the same district. The map drawers apparently assumed that State Senator Steve Newman, who had resigned from the Virginia Redistricting Commission, was not planning to seek re-election.37

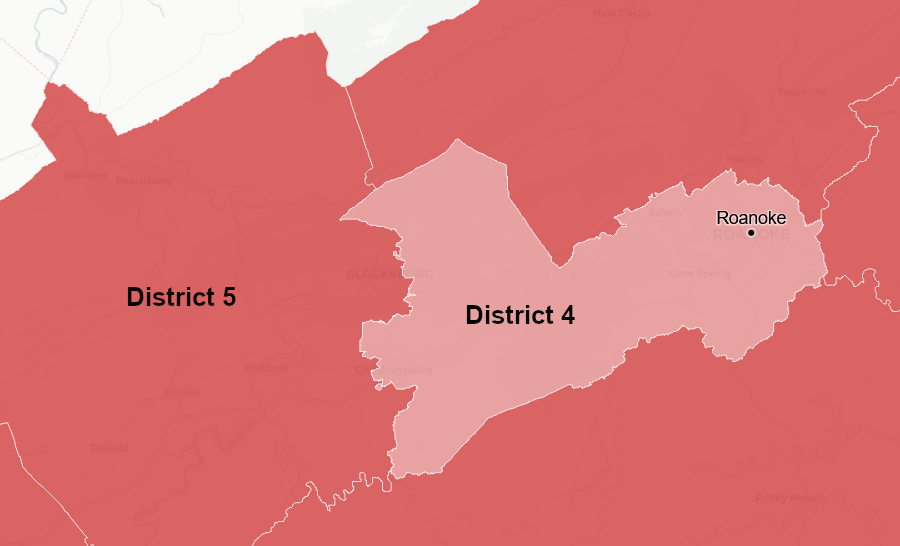

One commentator noted that while statewide races might be won consistently by Democratic candidates, the Democratic voters were concentrated in a smaller percentage of the state than Republicans. A gerrymander that ignored "compact and contiguous" criteria was the only way to put the isolated pockets of Democrats in Blacksburg, Roanoke, and Charlottesville into a US House of Representatives district that would be competitive. However Congressional district boundaries were drawn for those cities in 2021, the Republican-leaning voters in surrounding rural counties would dominate elections.

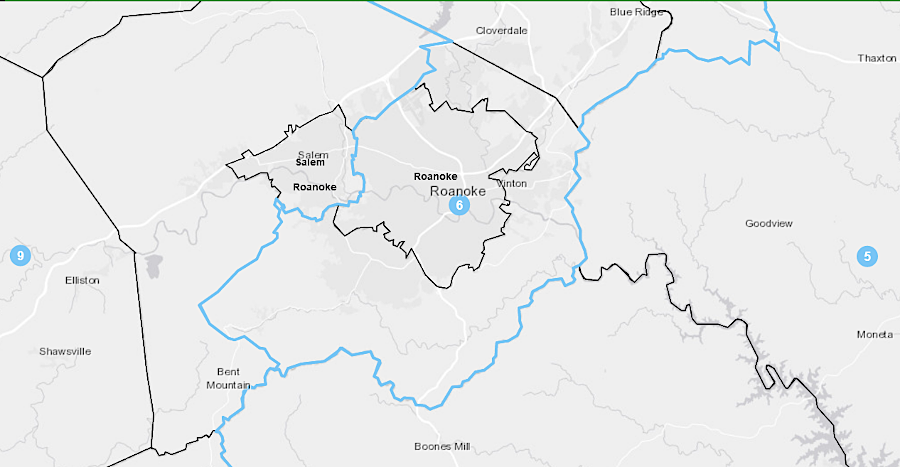

in 2011 redistricting, the City of Roanoke was kept in the 6th Congressional District

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Current Congressional (Court Ordered Modification 1/7/16)

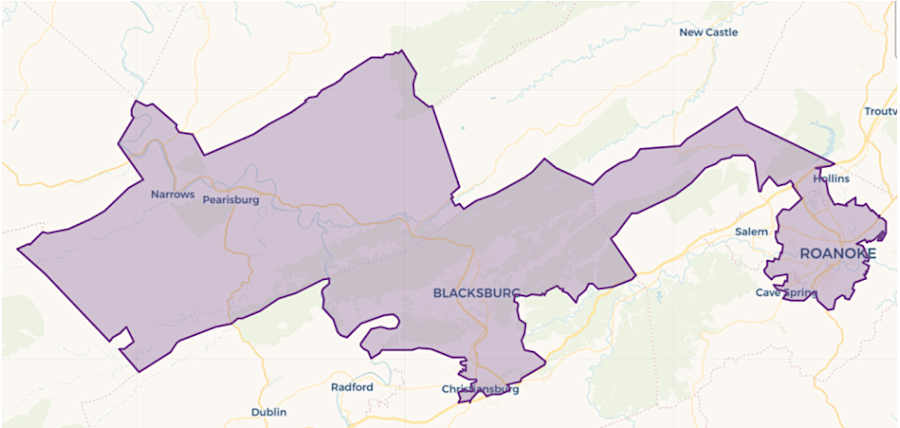

in 2011 redistricting, the Democratic-controlled State Senate had ensured Blacksburg and Roanoke were combined in District 21

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), State Senate District 21

the 2021 redistricting created two Republican-leaning districts, with Blacksburg in District 5 and Roanoke in District 4

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Virginia Redistricting 2021

Boundaries of compact and contiguous districts representing communities of interest inevitably include a high percentage of Democrats in Northern Virginia, Richmond area, and Hampton Roads. Democratic candidates are predicted to win in those districts by high margins, but a high percentage of other districts will be competitive or guaranteed for Republican candidates.38

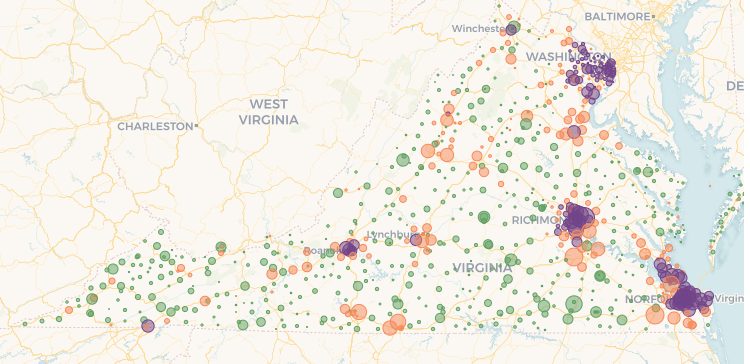

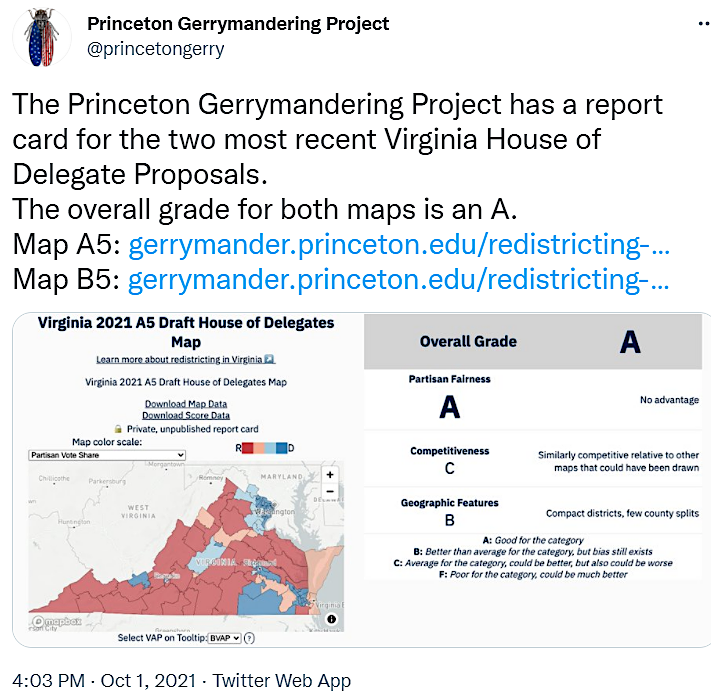

Though representatives of the two political parties could not produce a combined map for the 100 House of Delegates districts in early October, the Princeton Gerrymandering Project's Redistricting Report Card gave both Republican and Democratic early drafts an "A" for non-partisanship. The good start was not sustained; later drafts got lower marks, including an F.

early in the process, the Princeton Gerrymandering Project rated highly both Democratic and Republican draft maps for House of Delegates districts

Source: Princeton Gerrymandering Project

The differences between the two initial draft maps were primarily regarding the opportunity for election of candidates from minority ethnic groups. The Democratic proposals included two "opportunity districts" for Hispanic candidates and one district for an Asian candidate, while the Republican draft had one Hispanic opportunity district and three such districts for Asian candidates.

In addition, the Democratic draft proposed an additional opportunity district for black candidates in Hampton Roads. The Republican draft concentrated more black voters into two districts near Richmond. Based on the presumption that black voters supported Democratic candidates, packing them into a small number of districts would make the remaining districts more competitive for Republican candidates.

Consideration of race was challenging. A key 1965 Federal law banned voting discrimination based on basis of race, color or language, but equal treatment under the law also required ensuring the opportunity for candidates from minority groups to win elections. The 2011 redistricting resulted in 5 Senate and 12 House majority-minority districts, but Federal courts later required revisions of the House of Delegates district boundaries because they split up black voters.

The 2020 amendment to the state constitution which created the Virginia Redistricting Commission included:39

Democrats argued that boundaries should increase the number of districts involving politically cohesive groups, living closely together, to maximize the potential to elect black candidates. They cited the challenge in District 75. The Republicans had controlled the House of Delegates in 2011, and they drew the boundaries to ensure a voting-age population that would be 55% black.

Del. Roslyn "Roz" Tyler won with over 60% of the vote in 2017. After boundaries were adjusted by a Federal court and the percentage of black voters in the district was reduced, she won with just 51% of the vote.40

A Democratic member of the commission stated bluntly:

The Republican map-drawer in 2021 was involved in creating the unconstitutional boundaries after the 2010 Census, which affected the ability of the two sides to compromise on one map in 2021. Knowing that most black candidates would be Democrats, the Republican legal advisor justified concentrating the black voters into a smaller number of districts:41

Failure to choose one set of mapdrawers, followed by 8-8 decisions split along party lines, led to the commission reaching a point of failure just before its deadline to deliver a final map for General Assembly districts.

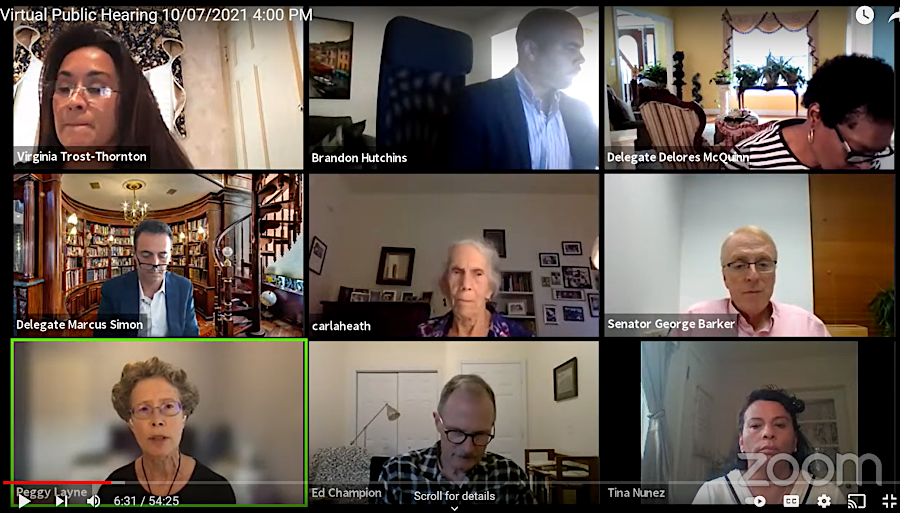

The commission was unable to agree on a single officially-proposed map to submit for public comment at the start of October. Instead, the public had to consider 21 separate House of Delegates proposals and 20 proposals for State Senate districts. The commission held eight virtual public hearings without offering a preferred proposal for public review.42

COVID-19 led to the commission holding virtual meetings, which increased public access to discussions and transparency of debates previously held in secret

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Virtual Public Hearing 10/07/2021 4:00 PM

Then on October 8, facing a deadline of adopting maps by October 10, the meeting started with a focus on four maps. Republican members had coalesced around a map for the House of Delegates districts and a map for the State Senate districts; Democrats had proposed a pair of different maps. The Democratic map for the State Senate was a new proposal that had received no public review.

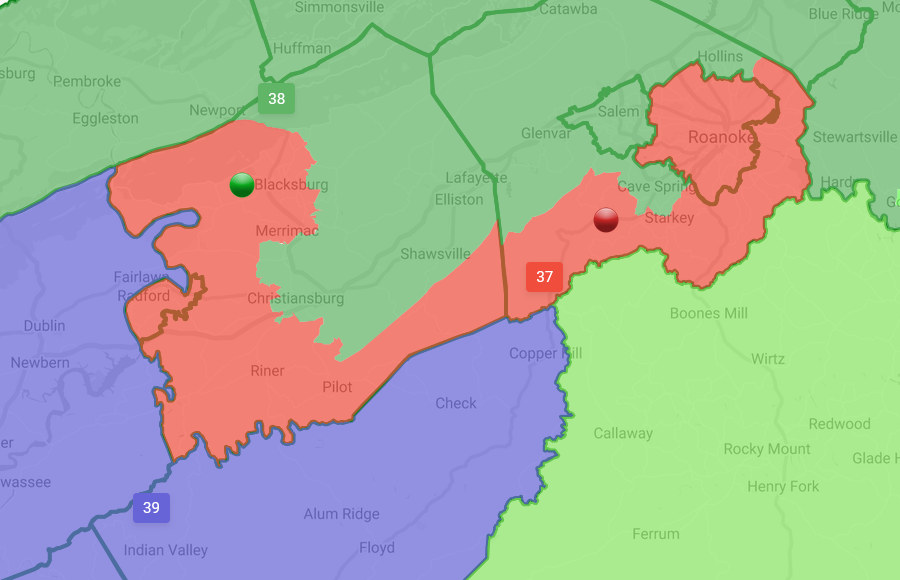

Democrats proposed a plan for a State Senate District that prioritized linking Democratic-leaning precincts in Roanoke and Blacksburg over "compact and contiguous" criteria

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, B4 Statewide SD

Republican members rejected a proposal by the Democratic members to pick one map for each part of the General Assembly, and to complete the process by refining those chosen maps. Democrats proposed starting with the map of State Senate districts produced by the Democratic map drawers and the map of House of Delegates districts produced by the Republican map drawers.

There were two more 8-8 votes where Republican members insisted on starting with a Republican version of the State Senate map. Democrats ended up abandoning their proposal to start with their new State Senate map and use a previously-proposed Democrat map and Republican map as starting points, but all eight the Republicans voted no. After a short recess, three Democratic citizen members left the meeting. That stunning action reduced attendance below a quorum and ended discussion for the day.

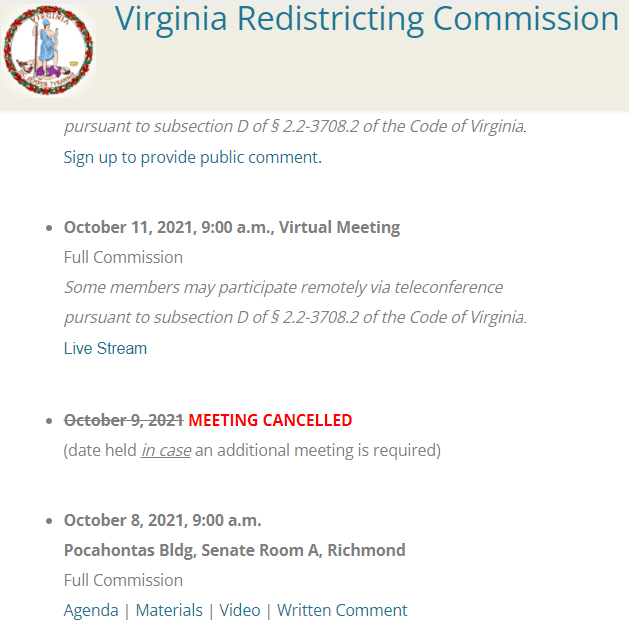

The very frustrated Democratic co-chair declared that she perceived no trust established across partisan lines, and no potential for 12 of the commission's 16 members (six of eight legislators, and also six of eight citizens) to agree on a map. She made clear that the Virginia Redistricting Commission process was over and, according to the 2020 constitutional amendment, the Supreme Court of Virginia would have to create the redistricting maps:43

There was no formal vote to adjourn, and the scheduled meeting on Saturday was cancelled.

the scheduled Saturday meeting of the commission was cancelled, after the collapse of negotiations and a walkout by Democratic citizen members on Friday

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Public Meetings

The State Senate map proposed by the Republican map drawers was significantly more partisan than the Democratic proposal. According to the Richmond Times-Dispatch:44

One commentator clarified that the decision to consider the home addresses of incumbents was not a factor in the inability to agree on new maps. Adjusting boundaries to protect incumbents was popular among legislators in both parties, and may have facilitated adoption of any proposed maps.

Instead, the commentator allocated blame for the Commission's failure to both Republican and Democratic members, after the meeting ended in failure on October 8. The partisan commission was never able to create a non-partisan process:45

the public could provide comments on all drafts proposed for review by the Virginia Redistricting Commission

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, C1 Statewide CD (Plan 364)

Another allocated blame on the structure of the commission, rather than on the 16 members who could not find a path to compromise:46

The chaotic end of the commission's efforts to draw maps for General Assembly districts and failure to adopt maps by October 10 still left open an option. The law creating the commission included an automatic 14-day extension beyond the deadline.

All 16 members of the commission chose to meet virtually again on October 11, but they explored how to notify the Supreme Court of Virginia that the commission would not revisit the General Assembly maps. The remaining time would be spent drawing maps for the 11 House of Representatives districts, in hopes of meeting the October 25 deadline for that process.47

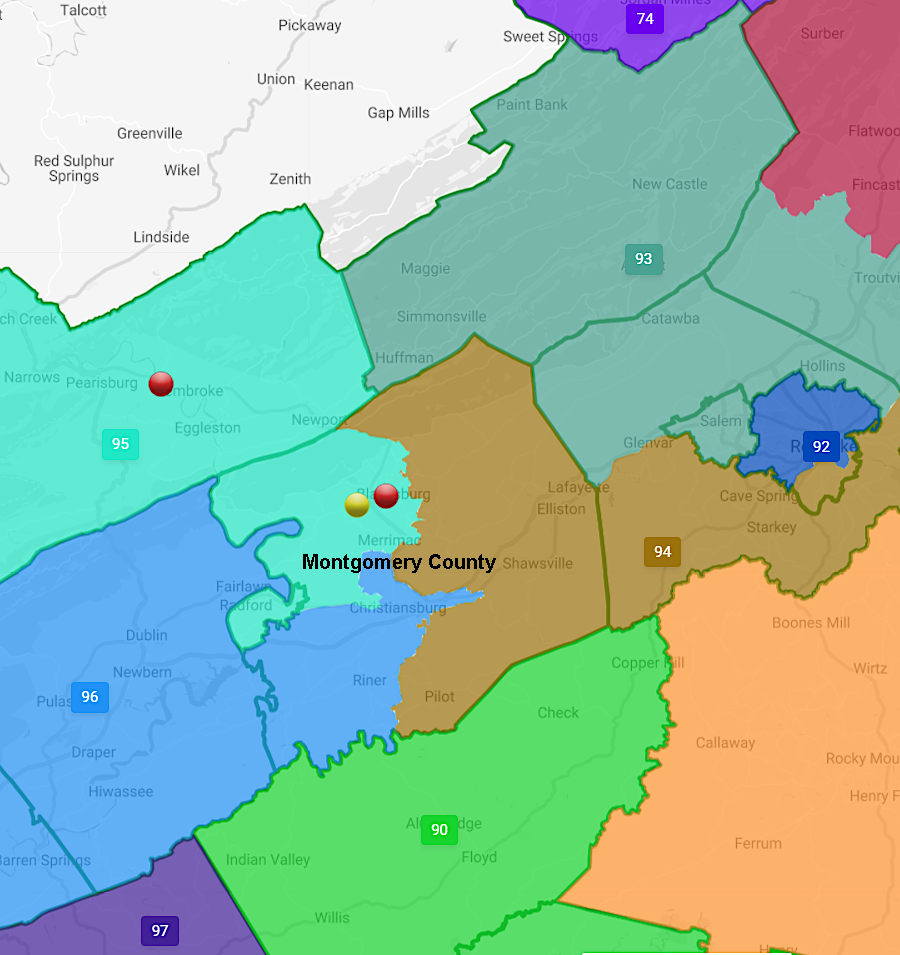

the collapse of the Virginia Redistricting Commission on October 8 meant that public comments on drafts, such as splitting Montgomery County into three House of Delegates districts, became irrelevant

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, B7 Statewide HOD

The commissioners negotiated a deal where the Democratic map drawers would propose boundaries for the 8th, 10th and 11th Congressional districts in Northern Virginia, while Republican map drawers would propose boundaries for the 5th, 6th, and 9th districts. The political tilt was so strong in those two regions that there was little opportunity to draw "compact and contiguous" boundaries that would result in a competitive two-party race.

The commissioners also agree to maintain the current boundaries of the 3rd and 4th districts, which a Federal court had defined. That deal left the Democrats with confidence they could win five of the state's 11 districts.

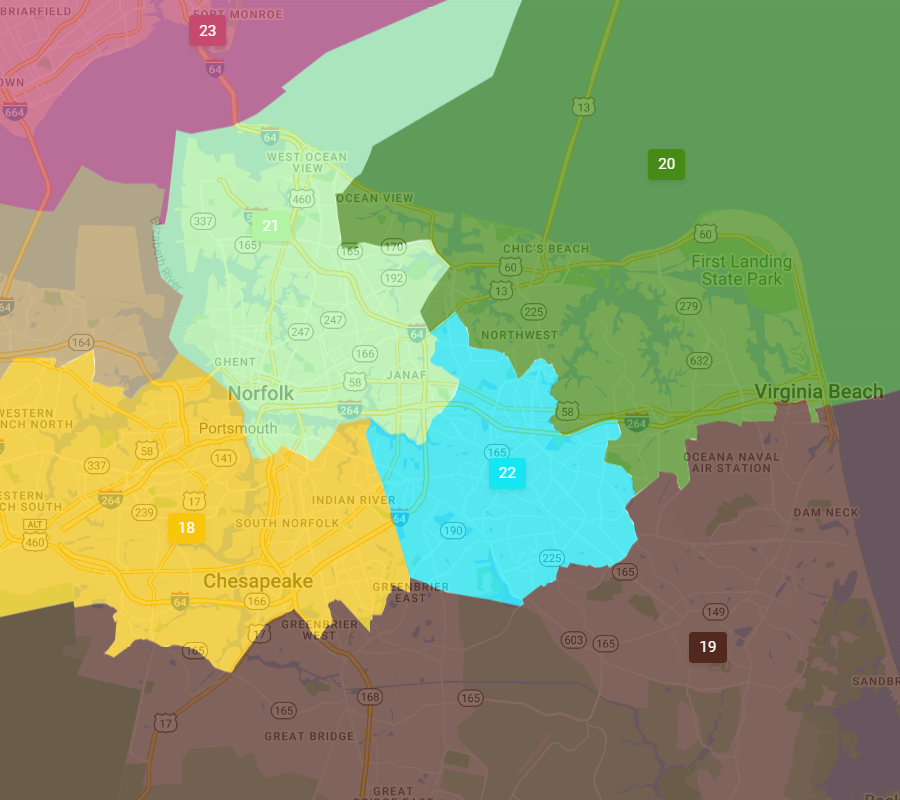

The commission's staff created a proposal for discussion with five districts that would be safely Republican, along with the five safely Democratic districts. The one highly-competitive district would be centered on Hampton Roads. At the time, there were seven Democrats and four Republicans serving in the House of Representatives. Three districts were competitive, with seats that had flipped from Republican to Democrat in 2018, but the boundaries of those districts had to be revised to reflect the population numbers from the 2020 Census.

the Virginia Redistricting Commission considered redrawing Congressional districts to create just one competitive "swing" district (purple)

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Commission - US House - C1

The discussion on Congressional maps at the Virginia Redistricting Commission soured almost immediately, once the Democratic members realized the staff's proposed map drew heavily upon a submission created by the National Republican Redistricting Trust. Even discussing the "Republican dream map" was challenging, even if the Democratic members ultimately decided the staff proposal was developed in a benign process without undue partisan influence behind the scenes.

One commentor noted:48

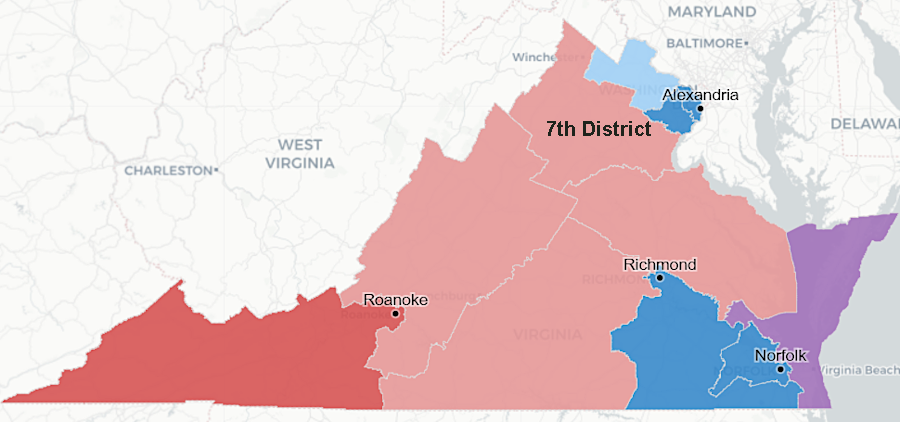

The final collapse of the commission's efforts occurred on October 20. Democrats proposed two maps that would create five safe Democratic districts, four safe Republican districts, and two "swing" or competitive districts. Republicans also created two maps, but with just one swing district and five safe Republican districts.

The dispute was centered on the 7th District, which could be redrawn to keep it competitive or make it safely Republican. The Republican map proposal moved many Democratic voters into what would be reliably Republican 1st and 5th districts. That would diminish the impact of their votes, leave Henrico County split between three districts, and make the 7th District reliably Republican as well. Democrats on the commission would not accept that proposed outcome.

Democrats drew boundaries of the 7th District (grey) to make it a swing district, rather than the staff's proposal for a reliably-Republican district

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, C1-A Statewide CD (Plan 420)

Democrats wanted the new election district maps to reflect "political fairness," acknowledging that in statewide elections the Democrats were winning consistently. At the time, the Republican and Democratic candidates for governor locked in a tight race. Virginia's recent reputation as a "blue" rather than "purple" state was in question.

The commission's votes on October 20 once again split along party lines. The eight Republicans endorsed their 5-5-1 map, and the eight Democrats endorsed their 5-4-2 map. That partisan deadlock was followed by a vote to adjourn permanently, without producing any maps for consideration by the General Assembly. The Democratic co-chair saw no reason to keep meeting and discussing the Congressional maps, even though the deadline for completing them was still five days away:49

In the end, the Virginia Supreme Court appointed special masters to draw new election boundaries for the US House of Representatives, House of Delegates, and State Senate. Those boundaries were set in December 2021.

For the upcoming 2022 US House of Representatives, both the Democratic and Republican nominees lived outside the boundaries of the new 7th District boundaries. For the 2023 elections for the State Senate, the boundaries of new District 20 included the homes of three incumbents. One chose to run for the US House of Representatives in 2022. If she lost that race, she would still be a State Senator in 2023 and could run for re-election.

McGuire Woods Consulting assessed the new political landscape, after the failure of the bipartisan Virginia Redistricting Commission to draw maps that offered incumbent protection:50

The court's redistricting in 2021 resulted in intra-party nominating contests which threatened incumbents in 2023. However, only about 25 of the 140 races in the general election were judged by political observers to be realistically competitive. In nearly 80% of the districts, a Republican or Democratic candidate was expected to get at least 55% of the vote. Whichever candidate won nomination by the dominant party in those districts by June 20 was highly likely to win the general election in November 2023.

Despite the court's realignment of district boundaries, the strong preferences of urban voters for Democrats and of rural voters for Republicans left a small percentage of districts with competitive inter-party races. A seasoned reporter observed:51

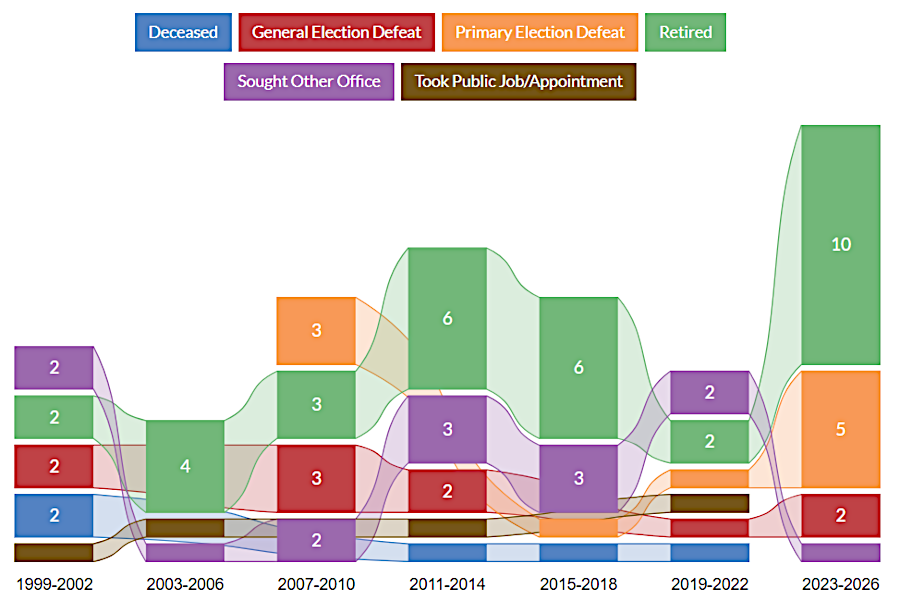

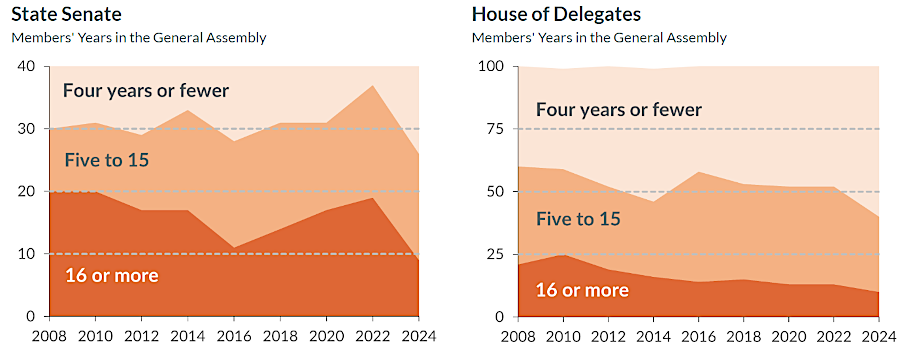

Between 2016-2023, half the members of the House of Delegates left office voluntarily or through election defeat but the top leaders remained in office. District boundaries had been drawn in 2011 so the party leaders rarely experienced a competitive election.

The 2021 redistricting did trigger a major turnover in the leadership of both the House of Delegates and the State Senate. The "people that have run the place" were forced into new districts, since the court-directed redistricting process did not protect incumbents.

Both the Senate Majority Leader and the Senate Minority Leader chose not to run for re-election. Almost half of the Republican committee chairs in the House of Delegates were not on the ballot in the November 2023 general election. Similarly, almost half of the 15-member Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee chose not to run in 2023.

The installation of new leaders after the 2023 election created the opportunity to pass legislation that had traditionally been blocked, such as paid family leave. The loss of institutional memory also created the potential that lobbyists with expertise in specialized programs would gain greater influence with legislators who had less experience.

OneVirginia2021 led a successful Fair Maps campaign, though it had not intended for the Supreme Court of Virginia to draw the boundaries. The chair of the Republican Party of Virginia commented on how the changes coming after the 2023 elections, based on the 2021 redistricting maps, would impact both political parties:52

As a result of the delay, the 2021 election for the Virginia House of Delegates were based on the "old" election districts which did not reflect the 2020 Census data.

The 2021 election was a sweep for the Republicans in the three statewide races for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General. Those races were not affected by redistricting, but Republicans also took control of the House of Delegates. Democrats who were upset at that loss soon punished Eileen Filler-Corn, who had been Speaker in 2020. She had refused to block the bill allowing Virginia citizens to vote on create the redistricting commission. Blocking the bill would have blocked the constitutional amendment, thus allowing the Democratic majority in the House of Delegates and State Senate to gerrymander district boundaries in the traditional process to protect incumbents.

After the 2021 election, the remaining Democrats in the House of Delegates elected Eileen Filler-Corn to serve as minority leader. However, once the General Assembly started its 2022 session, the Democrats held a special election and voted the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House of Delegates out of that leadership role. The caucus chair was elevated to minority leader and Filler-Corn became a back-bencher for the session. In 2023, she announced she would not run for re-election, while hinting she might run for governor instead in 2025.

When redistricting was delayed in 1981, a court ruled that a new House of Delegates election was required in 1982 using the new boundaries. The delegates elected in 1981 served just a one-year term, as did the delegates elected in 1982. Those elected in 1983 returned to two-year terms.

A lawsuit was filed to force new House of Delegates elections in 2022, matching the 1981 experience. Since the Republicans had flipped enough districts in 2021 to take control of the House of Delegates, a new election in 2022 would have given Democrats a chance to regain the majority. The legal process was delayed, and in June, 2022 a panel of three Federal judges ruled that the plaintiff lacked legal "standing" and no special election would be required for the House of Delegates.53

That decision was followed by a new lawsuit from an individual with legal "standing." The Federal judge hearing the case demanded speedy action. The judge suggested that former Attorney General Mark Herring had intentionally delayed a legal decision, in a political effort to "run out the clock" and prevent a 2022 special election. If the Federal judge required a special election, then primaries would have to be scheduled to select candidates just a few months before the general election on November 8, 2022.

However, in August 2022 a Federal court ruled that early elections would not be required. The court concluded that forcing 100 members in a House of Delegates elected in 2021 to leave office only halfway through its term was too great a remedy for the harm caused by failure to redistrict in 2020. The election officials being sued were not responsible for the delay by the Bureau of Census in delivering the data needed to redistrict, and:54

After the lawsuit was settled and it was clear that 100 new House of Delegates elections would not be held in 2022, the nonpartisan advocacy group OneVirginia2021 reorganized as UpVote Virginia. Former Governor George Allen was the primary speaker when the new organization was launched. He highlighted the advantages of ranked choice voting, which the Republican Party used successfully to choose nominees for statewide races at the 2021 convention. UpVote Virginia also identified several other issues which it had prioritized, along with ranked choice voting:55

OneVirginia2021 reorganized as UpVote Virginia in 2022

Source: OneVirginia2021 Foundation, Big News!

When two or more incumbents were placed in a new district, one option was to move to another district - especially if that district had no incumbent - for the 2023 election. That approach was complicated by a provision in the Constitution of Virginia:56

To establish residency and qualify for the 2023 ballot, incumbents could move to an area that was within the boundaries of their "old" district as well as the new district. There were many such "overlapping areas" after redistricting, but in some cases an incumbent might decide to move to a new primary residence outside their current district and establish residency there before the "veto session" of the 2023 General Assembly.

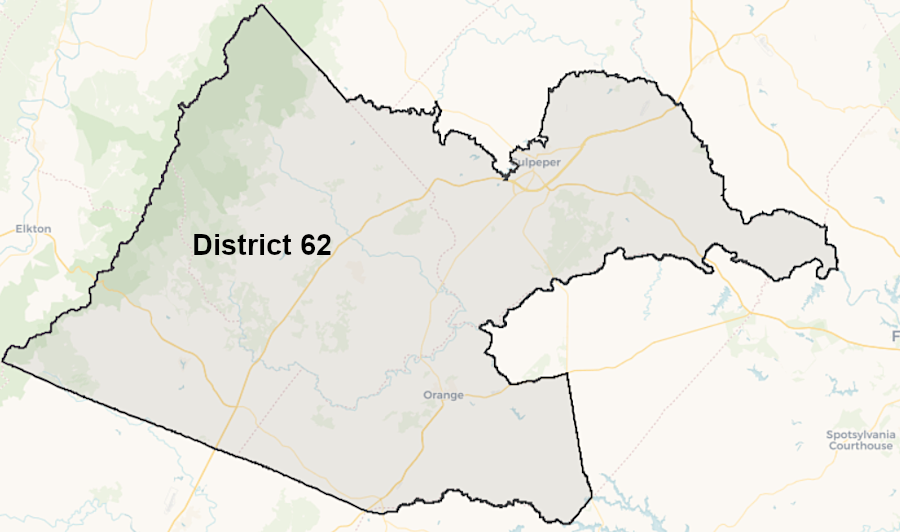

When boundaries of District 30 of the House of Delegates were redrawn in 2021, 75% of the voters ended up in the new District 62. However, the home of the incumbent, Delegate Nick Freitas, ended up in District 61. Rather that run against a fellow Republican in District 61, Del. Freitas moved into a home nine miles away owned by his mother. His family and livestock remained at his original home, but his official residence changed to District 62.

Delegate Nick Freitas moved his official residence nine miles in 2023 so he be eligible to run in District 62

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Big News!

If that occurred, the incumbent would be forced out of office until potentially being re-elected and returning to serve again the General Assembly in January 2024. One or more vacancies could alter the close political balance between Republicans and Democrats in any remaining sessions of the 2023 General Assembly.

The first session of the 2023 General Assembly failed to complete legislation to amend the state budget, authorizing expenditure of a $5 billion surplus in state revenues. A "skinny" budget was approved to spend a portion, but a special session was expected to be called for allocating the remainder.

The ability to participate in that anticipated special session was constrained by the requirement for legislators to live in their new districts long enough to be eligible to qualify for the ballot in November 2023. Legislators had to file paperwork by April 6 noting their new address in a new district. As some legislators interpreted the law, that filing would force them to vacate their current office and lose the right to serve in the reconvened "veto" session on April 12 or in a special budget session.

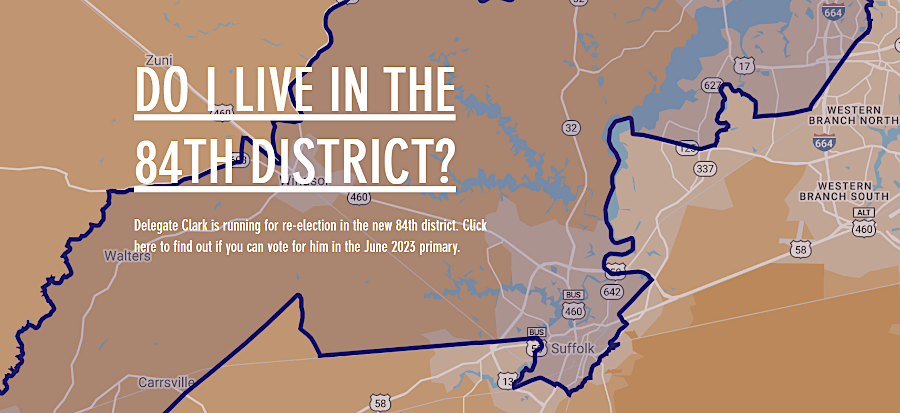

The first to announce a planned resignation in order to qualify for a new district was Del. Nadarius Clark. He had been elected to the House of Delegates in 2021 from District 79 in Hampton Roads, but planned to run in 2023 in District 84. He acknowledged in mid-March that he would lose the opportunity to attend a special session held after April 6, 2023:57

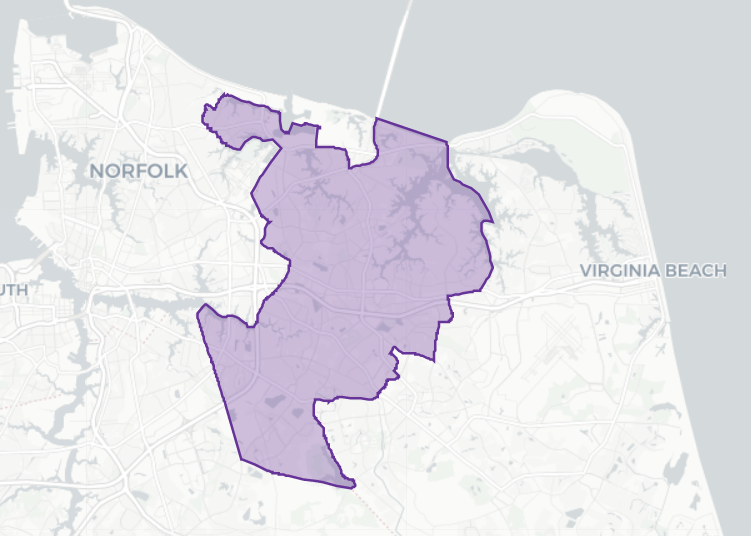

A State Senate vacancy was created in November, 2022. Republican State Senator Jen Kiggans defeated the incumbent Democrat, Rep. Elaine Luria, and won the 2nd District seat in the US House of Representatives. Redistricting in 2021 had moved many Democrats in Norfolk out of the 2nd Congressional District, helping Republicans flip the seat in the 2022 election.

One observer credited the redistricting by the Virginia Supreme Court, rather than by partisan legislators, with that Republican victory:58

The victory by Kiggans triggered a special election for her 7th District seat. The special election used the same boundaries that were in place in 2019 when Kiggans had been elected to serve a four-year term, and not the new State Senate district boundaries created in the 2021 redistricting process. The new redistricted boundaries were not used until the November 7, 2023 election for General Assembly seats.

A Democrat, Aaron Rouse, won the special election. His replacement of Jen Kiggans gave the Democratic Party a 22-18 majority in the State Senate. Because the Democratic Party already had a majority, and the "blue wall" had stayed united and blocked various Republican initiatives after the 2021 election. the shift in the 7th District from Republican to Democrat in th special election had no impact of the partisan balance within the General Assembly through the end of 2023.59

the special election to replace State Senator Jen Kiggans used the 7th District boundaries of 2011 redistricting, not the new boundaries established in 2021

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Special Election: Senate District 7

different district boundaries, as well as different numbers for State Senate seats, were in place for the 2023 election for State Senate after 2021 redistricting

Source: Supreme Court of Virginia, SCV Final Senate Districts Map (interactive)

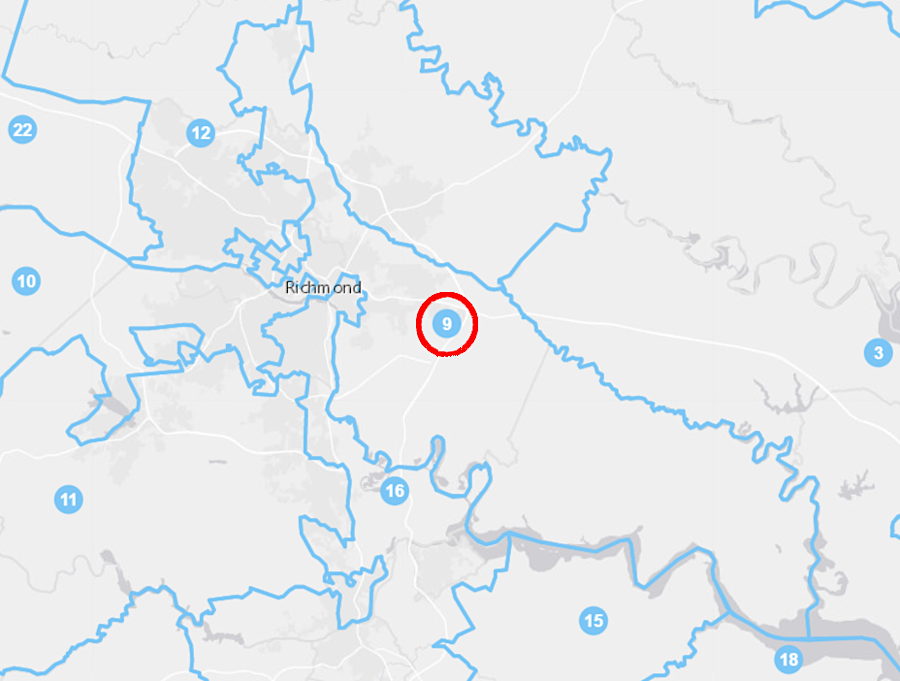

A series of special elections were triggered in early 2023, after US Representative Donald McEachin died soon after re-election to his 4th District seat in 2022. State Senator Jennifer McClellan won the election, so a special election was required to fill her 9th District seat.

Del. Lamont Bagby won the race to replace her. That restored the 22-18 Democratic-Republican balance in the State Senate for the remainder of the 2023 session.

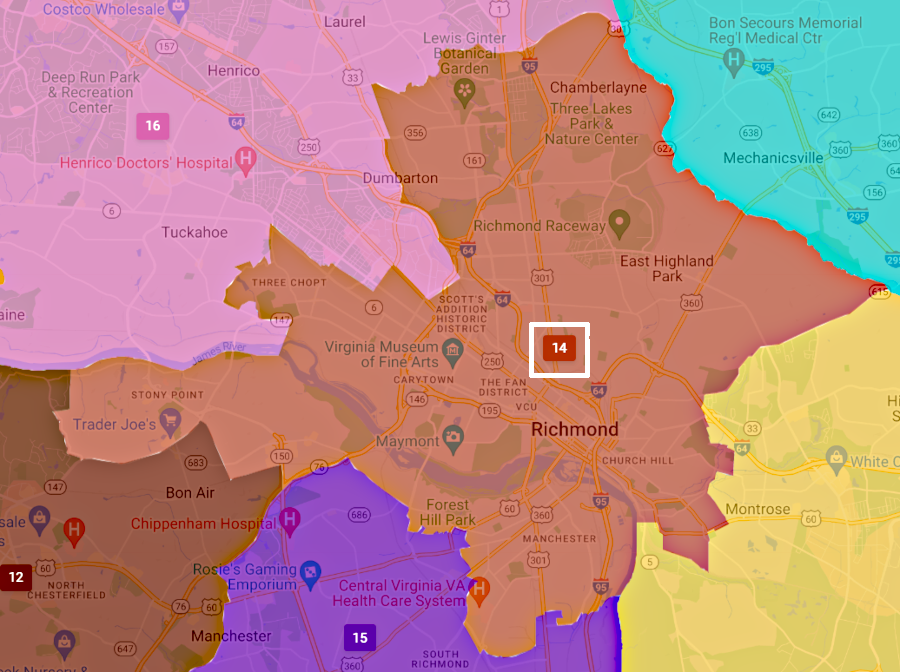

Bagby sought to represent some of the 74th District voters, plus voters in new precincts, when he campaigned successfully for the 9th District State Senate seat in the March 2023 special election. To win the November 2023 general election, however, he had to appeal to a third set of voters within the boundaries of the 14th State Senate District.

He campaigned in one set of precincts to win the 74th District seat in November 2021, a different set of precincts in February/March 2023 to win the special election for the 9th District State Senate seat, then a third set of precincts in his effort to win the June 2023 primary for the 14th District State Senate seat. All of the special elections in 2023 used boundaries for Congressional and General Assembly districts that had been established prior to the December 2021 redistricting decisions of the Virginia Supreme Court.

His 74th District seat remained empty in the House of Delegates for the rest of 2023. Democratic and Republican leaders in the General Assembly agreed that no special election should be called to fill that seat before the regular November 2023 election date. Democratic leaders claimed the Senate had not adjourned so the General Assembly was still in session, so the Speaker of the House of Delegates rather than the governor had the authority to call for a special election. Both the Speaker and the Governor concurred that no election should be called, which finessed the issue of who had the authority.

the special election for the 9th District in the State Senate in March 2023 used the boundaries established in the 2011 redistricting

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, 2011 Interactive Maps

the special election for the 9th District in the State Senate in March 2023 was followed by an election for the new 14th District in November 2023

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, SCV Final Senate Districts Map (interactive)

The effort required to nominate and elect a replacement for Bagby involved too much work for too little benefit because:

- the anticipated special session on the budget was likely to be completed before a new member could be elected to fill behind Bagby

- the current 74th District boundaries would evaporate at the end of 2023 due to redistricting

- the expected victory of a Democratic candidate would not affect the power balance in the Republican-controlled House of Delegates

For the same reasons, no special election was called in 2023 for the "old" 79th House District or the 83rd District. The incumbent in the 79th House District resigned in March 2023, after moving to establish residency within the boundaries of the new 84th District as defined by the 2021 redistricting process. He was seeking the Democratic Party nomination in the new district, and under state law he automatically was disqualified from representing the 79th District after moving outside its boundaries.

The incumbent in the 83rd District also resigned in order to run for a State Senate seat. He too moved in order to qualify.

no special election was held after the incumbent in the 79th District moved in March 2023 to qualify for election from the new 84th District, leaving the 79th District unrepresented for the rest of the year

Source: Nadarius Clark for Delegate

As a result, the General Assembly reconvened for its veto session on April 12 with three empty seats. Politically, electing two replacement Democrats would not affect the power of balance in the House of Delegates. The Henrico County Registrar articulated the burden that another special election would impose:60

After the 2021 redistricting maps were finalized, Del. Glenn Davis chose not to run against a fellow Republican. He resigned in April 2023 in order to become the Director of the Virginia Department of Energy, appointed by Governor Youngkin to continue public service in the Executive Branch. His resignation left the House of Delegates with just 96 members.61

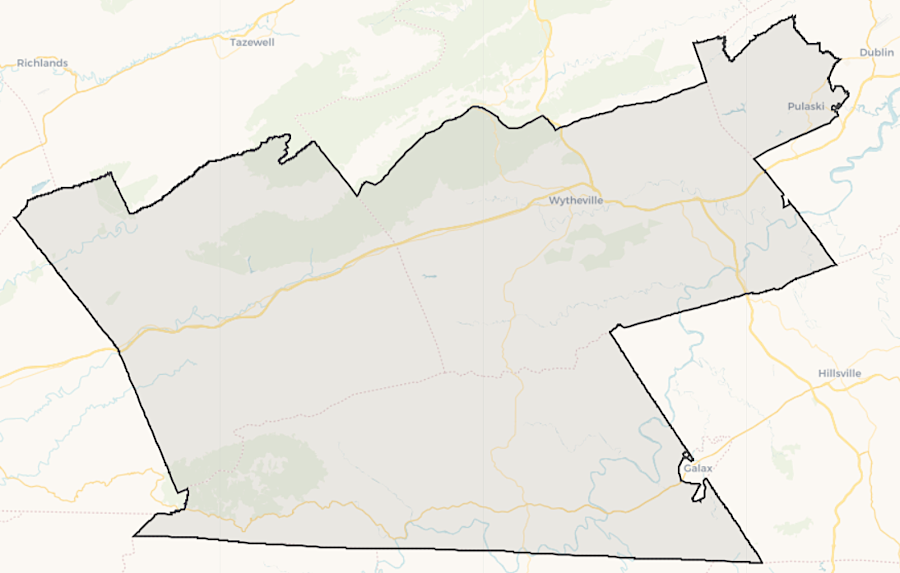

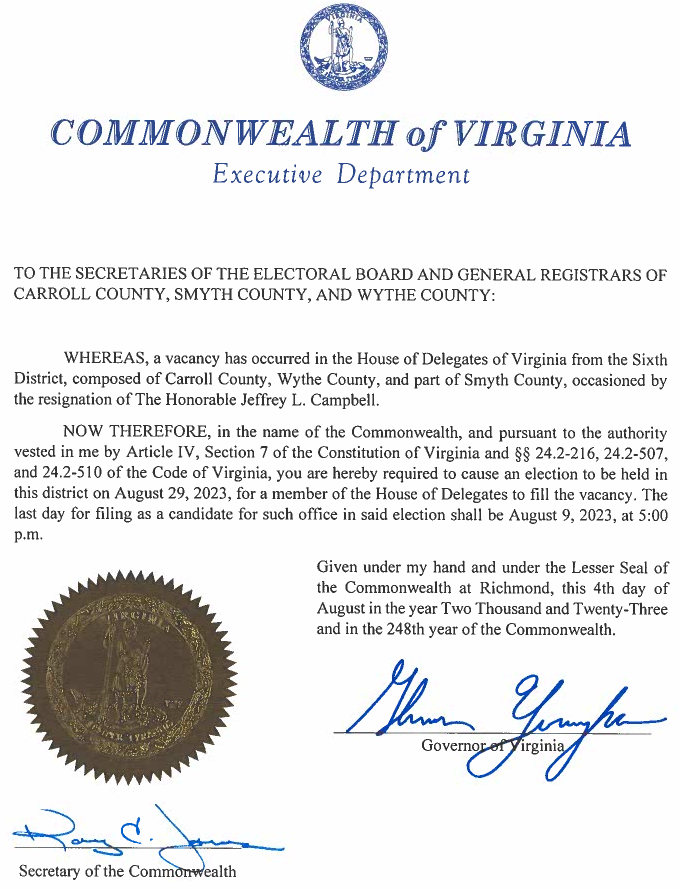

Del. Jeff Campbell resigned his 6th District seat in the House of Delegates in July 2023, in order to accept appointment as a General District Court judge. The local judges in the 28th Judicial Circuit chose Del. Campbell to be a new judge, with the expectation that the General Assembly would confirm his appointment within 30 days of reconvening.

Governor Youngkin determined that a new state law, which went into effect on July 1, required him to issue a writ of election within 30 days of the vacancy created by Del. Campbell's resignation.

The winner of the August 29, 2023 special election was destined to serve the 6th District only for four months. It was unclear if the General Assembly would meet for even one day within that time period. In addition, whoever won election in November 2023 would be the last to represent the boundaries of the 6th District as drawn a dozen years earlier in the 2011 redistricting. Most of those voters were scheduled to elect a new delegate for the 46th District on November 7, 2023.

a special election was required on August 29, 2023 to fill a vacancy in the 6th House of Delegates district, using 2011 redistricting boundaries

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Current House (Court Ordered Modification 1/29/2019)

on November 7, 2023, many of those same voters were electing a member of the House of Delegates from the 46th District

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), House of Delegates District 46

Del. Campbell's aide, Jed Arnold, was favored heavily to win both elections; the political balance of the House of Delegates would not have been impacted if the seat had been left vacant. Campbell could have spared the district the cost of a special election if he had resigned before the new law went into effect on July 1, or later when another section of the Code of Virginia prohibited a special election within 55 days of a general election.

However, Democratic leaders of the General Assembly challenged the authority of the 28th Judicial Circuit judges to appoint Del. Campbell or for Gov. Youngkin to schedule the special election. Those leaders contended that the State Senate did not vote to adjourn "sine die" at the end of a special session in 2022. Since the General Assembly was still in session, at least by the interpretation of the Democrats, only the legislature had authority to appoint judges and only the Speaker of the House (not the Governor) had the authority to schedule a special election for the 6th House of Delegates district.

The special election was held as scheduled on August 29, 2023. By winning it, and then the general election in November in which he was the only name on the ballot, Jed Arnold gained seniority over all the other new members in the House of Delegates. Because redistricting led to so much turnover, he gained a step ahead of one-third of the members.

Del. Arnold was able to vote when the General Assembly returned on September 9, 2023 to approve a revised budget. On that day, there were four empty seats in the House of Delegates and one empty seat in the State Senate.62

Governor Youngkin determined he was forced by a new state law to schedule a Special Election for the soon-to-disappear 6th District

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Writ for Special Election, HD-6

After the June 20, 2023 primaries, it was clear that the 2021 redistricting would dramatically transform the 2024 General Assembly. One third of the 140 members would be new, with at least 15 new State Senators and 33 new members in the House of Delegates.

One Republican State Senator was defeated in the primaries, together with four Democratic State Senators with long seniority. In Fairfax County, both State Senator George Barker and State Senator Chap Peterson lost to younger, more liberal candidates in Democratic primaries. Each of those two incumbents had raised over $1 million in campaign contributions, while the amount raised by the two challengers combined was less than $1 million.63

Some generational change was anticipated in the 2023 elections as baby boomers aged out, but the loss of institutional memory was extraordinary. The State Senate Finance & Appropriations Committee was dramatically impacted by the retirements and primary defeats. Of the 15 members on the committee, nine chose to retire or were defeated - including both of the co-chairs.

That committee is one of the most important in the General Assembly, filled with the most-experienced legislators. They negotiate the state budget with counterparts in the House of Delegates and the Governor; the other 25 members of the State Senate do not get to participate in the decisionmaking until the final deal requires a vote. As a result of the retirements and defeats, 137 years of legislative experience would not return to the Senate Finance & Appropriations Committee in 2024.

After the November 2023 election, the senior Republican on the Senate Finance & Appropriations Committee received a cancer diagnosis that caused him to retire. That removed an additional 20 years of legislative experience, and led to the 2/3 of the 2024 committee having new members.

The traditional rise to power, through accumulating seniority after being elected repeatedly, was destabilized. It was clear that Republican Glenn Youngkin would still be Governor in 2024, but neither political party could be confident that it would control either of the two houses of the state legislature.

One possibility was that the Republicans would win both houses and have a "trifecta" of control with the Governor. When the Democrats had such control in 2020-2021, they passed a series of laws to implement policies that Republicans had opposed for the last decade. If the Republicans gained similar control after the 2023 elections, that party could implement its policies on issues such as abortion.

A former member of the House of Delegates commented:64

In a clear cntrast to the past, the 2021 redistricting was *not* designed the benefit one political party over another. In 2023, when all 140 seats in the General Assembly were on the ballot, incumbents in multiple districts were forced to introduce themselves to new voters who had no history of previously supporting or opposing that candidate. The benefits of incumbency over new office seekers were minimized.

On November 7, 2023, Democrats regained control of the House of Delegates with a 51-49 majority and retained control of the State Senate with 21-19 majority. The diversity of people elected to the General Assembly was historically high, with seven blacks elected to the 40-member State Senate. For the first time in history the Speaker of the House would be a black man (Del. Don Scott) and there would be black leaders for the powerful "money committees," the Senate Finance Committee (Sen. Louise Lucas) and the House Appropriations Committee (Del. Luke Torian) .

Millions of dollars were spent to affect the partisan outcome, but the redistricting boundaries may have had more impact on the outcome than the advertising, door knocking, or even the Get Out The Vote efforts. Winning election after being moved into a district with another incumbent, or where voters had no track record of support, created a major challenge that a significant number of incumbents chose not to face.

After the 2021 redistricting, there were 21 open seats (for which there was no incumbent) in the House of Delegates. New district boundaries were a major factor in the decisions of 16 members to retire and for 14 members to seek election to the State Senate. By the end of November 7, 2023, one additional member had resigned to take another public job, one more had been defeated in a primary, and two others were defeated in the General Election. Of the 100 delegates in 2024, 34 (34% of the House of Delegates) were new.

In the State Senate, there were 9 open seats. That was one reason so many delegates sought to move up to the State Senate, where members are elected for four year terms rather than have to run every two years. In the State Senate, 11 of the 40 incumbents chose not to run for re-election. One member left after she was elected to the US House of Representatives in a special election. In the June 20 primary, five more incumbents were defeated; another two lost in the General Election, and one retired for health reasons after the November 2023 general election.

Of the 40 senators starting in 2024, 17 (43%) were new to that legislative body. Some had served previously in the House of Delegates, and one member had served an earlier term but had been defeated for re-election in 2019.

In his address to the General Assembly on January 10, 2024, Governor Youngkin noted that 54 of the 140 members (39%) were sitting in new seats. That unusually-high number was triggered in large part by the inability of incumbents to choose their voters in the 2021 redistricting process. Legislators were also sitting in new offices after completion of the new General Assembly building, with its new tunnel to the Capitol.65

the 2021 redistricting led to a record number of new members in the State Senate in 2024

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Turnover in the State Senate and Loss of Institutional Knowledge

A former Republican member of the House of Delegates stated in frustration, after it became clear that the Democrats would control the General Assembly:66

A Democratic delegate concurred, saying:67

The traditional gerrymandering of the House of Delegates districts in 2001 and 2011 had allowed Republican candidates to win 5% more seats in that legislative body than their percentage of total votes. The 2021 redistricting created more balanced results. One analyst noted regarding the 2023 election:68

The importance of redistricting and how close votes in swing districts shape elections was made clear in 2024. After the 2023 ballots were counted, including two special elections in January 2024, Democrats controlled both chambers of the General Assembly by the narrowest of margins. The partisan balance was 21-19 in the State Senate, and 51-49 in the House of Delegates.

The Democratic majority, though thin, was a majority. The Democrats rejected several major budget intiatives proposed by Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin. They recognized that he could veto bills and budget amendments in response, but the governor was limited to just one term. A Democratic delegate commented before the veto session in April 2024:session:69