the exercise yard at the State Penitentiary in Richmond, which closed in 1990

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory, Virginia State Penitentiary Photograph Collection

the exercise yard at the State Penitentiary in Richmond, which closed in 1990

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory, Virginia State Penitentiary Photograph Collection

Incarcerating a prisoner was not a simple challenge in colonial Virginia. The initial structures built by the English were "earth fast," meaning the frame was placed directly on the ground without a stone foundation and wood in moist soil rotted within a few years.

A brick jail with a stone foundation was the obvious alternative, but Virginia colonists could not afford to build many brick buildings until a century after landing at Jamestown. There was no long-term imprisonment for major crimes in colonial Virginia. Many crimes in colonial Virginia were punished by fines, a whipping, or by being placed in the "stocks" where the public could see them.

In addition, feeding a prisoner while prohibiting him from working was a high burden to impose on the rest of the colonial Virginians who paid taxes to finance government operations. The lower the cost of government operations, the lower the taxes. It made more sense to impose a fine or a whipping, rather than to impose a jail sentence to punish criminal behavior. A common crime was for indentured servants to run away before serving their time, and the typical punishment was to extend the term of service. By using a financial or physical punishment rather than imprisonment, the community was not burdened by the costs of jails or jailors.

The opportunity to extract value from slave labor was not wasted by imprisonment. Punishment for slaves convicted of crimes included cropping ears and whipping backs. Local county courts were authorized to condemn a slave to death, though white convicts accused of a capital crime had to be sent to Williamsburg for trial by the General Court.

If a slave was executed for committing a capital crime in pre-Civil War Virginia, the slaveowner was reimbursed the value of the slave. The rationale was that unless slaveowners were reimbursed, they would hide their slaves from execution, protecting their personal economic investment but exposing the community to the risk of future criminal behavior.

During the pre-Civil War era, fears of slave insurrections were always present. The number of actual armed rebellions were few, but individual resistance was common. In cases where the slave was convicted of a crime and expected to remain a troublemaker, the slave might be shipped to a more-southern colony or to the West Indies where conditions were more brutal.

Local courts handled civil and almost all criminal cases, along with legislative issues and executive management of the county, after county governments in Virginia were established in 1634. Local jails were built next to local courthouses to hold prisoners until the members of the court would assemble each month. When debtors were imprisoned to try to "encourage" them to repay their obligations, the debtors themselves (or the creditors demanding to be paid) were required to pay for the room and board at the county jail.

Criminal justice was usually very swift, though civil issues often involved delays until witnesses were gathered and evidence submitted. If a case was a capital crime (meaning a verdict of guilty would be followed by execution), the local court would meet and direct that the defendant be transferred to Jamestown or Williamsburg for trial by the colonial General Court, which met every three months.

There was no Death Row in colonial Virginia. People convicted of capital crimes were executed at the gallows in Jamestown or Williamsburg soon after the General Court condemned them. Admiralty courts also had the power to order executions, and some pirates associated may have been hung at Hampton. Their prison before trial and execution was the HMS Pearl, the British warship which sailed to North Carolina and ended Blackbeard's reign in 1718.1

Shortly after the capital of Virginia was moved from Jamestown to Williamsburg in 1699, a sturdy brick "gaol" (jail) was constructed in Williamsburg next to the colonial Capitol building. The whole jail was 20x30 feet, which is the size of a modern great room in today's suburban homes. In the first version of that tiny jail, there were two even tinier 10x10 foot cells.2

The sanitary and jail crowding standards of that time were far different than today. In 1779, seven prisoners were incarcerated in just one cell, and that space included the toilet. The top British official captured at Detroit, Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, wrote:3

At the time of the American Revolution, a new concept in punishment was advocated by the Quakers in Pennsylvania. They proposed to reform criminals by placing them in a building for a period of time, during which they could contemplate their past, become penitent, and change their behavior before being released.

Thomas Jefferson led the charge in Virginia to modify state laws, and he proposed a "Bill for Proportioning Crimes and Punishments in Cases Heretofore Capital" in 1785. Jefferson also sketched out designs of a prison where people could be held in solitary confinement to labor and to reflect upon their sins.

In 1786, the General Assembly adopted a modified version of Jefferson's bill, and in 1800 a state penitentiary was built in Richmond. That structure represented the new approach to punishment, with imprisonment preferred over physical punishment or execution.

For nearly two centuries, the "state pen" was located west of the state capitol, on a ridge overlooking the James River next to the modern Lee Bridge. Redevelopment of downtown Richmond was enhanced in the 1980's by the razing of the state prison. The site is now the research center for Ethyl Corporation.

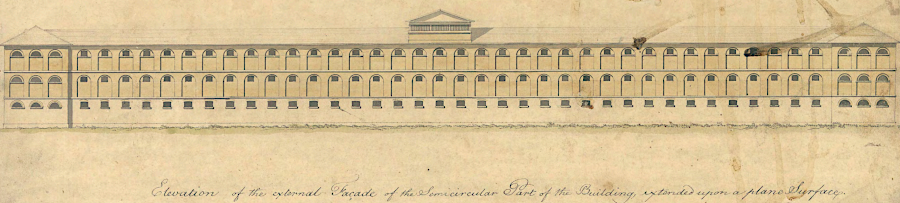

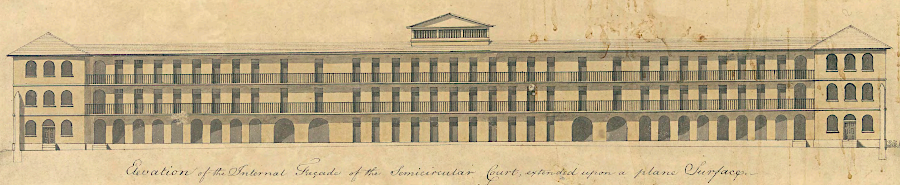

Benjamin Henry Latrobe planned the state prison built in Richmond

Source: Library of Virginia, Benjamin Henry Latrobe Collection, Virginia State Penitentiary - proposed plans, elevations, and perspective drawings

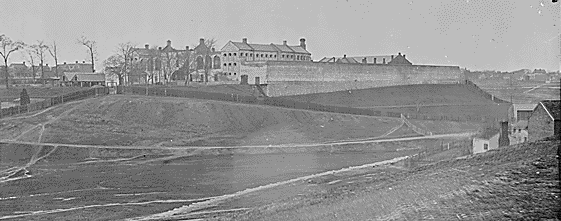

state penitentiary in Richmond, 1865

Source: National Archives, State Penitentiary, Richmond, Va

the state penitentiary was located west of the Capitol on Byrd street for nearly two centuries

Source: National Archives, Map of City of Richmond, Virginia (c.1858)