the State Penintentiary in Richmond held prisoners from 1800-1990

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory, Virginia State Penitentiary Photograph Collection

the State Penintentiary in Richmond held prisoners from 1800-1990

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory, Virginia State Penitentiary Photograph Collection

The Virginia Department of Corrections has built numerous new prisons in the 1990's. More prison beds were required by court decisions forcing better treatment of prisoners, and the state anticipated a need to house more prisoners resulting from "get tough" policies on crime. Most significantly, the General Assembly abolished parole under then-Governor George Allen, and funded new prisons to house inmates longer until their full sentences were completed.

In 2003, Virginia hired a private company to manage one prison, the Lawrenceville Correctional Center. The Virginia Department of Corrections did not renew the contract in 2024, and determined that state employees would serve as guards, staff, and managers starting on August 1.

That was part of a decision to close four other facilities: Augusta Correctional Center, Sussex II State Prison, Haynesville Correctional Unit #17 and Stafford Community Corrections Alternative Program (CCAP). That left the Virginia Department of Corrections with 36 other facilities, including state prisons, correctional centers and units, and work centers. Two were dedicated to housing female prisons, the Fluvanna Correctional Center for Women in Fluvanna County and the Virginia Correctional Center for Women in Goochland County, plus the Chesterfield Women's Community Corrections Alternative Program.1

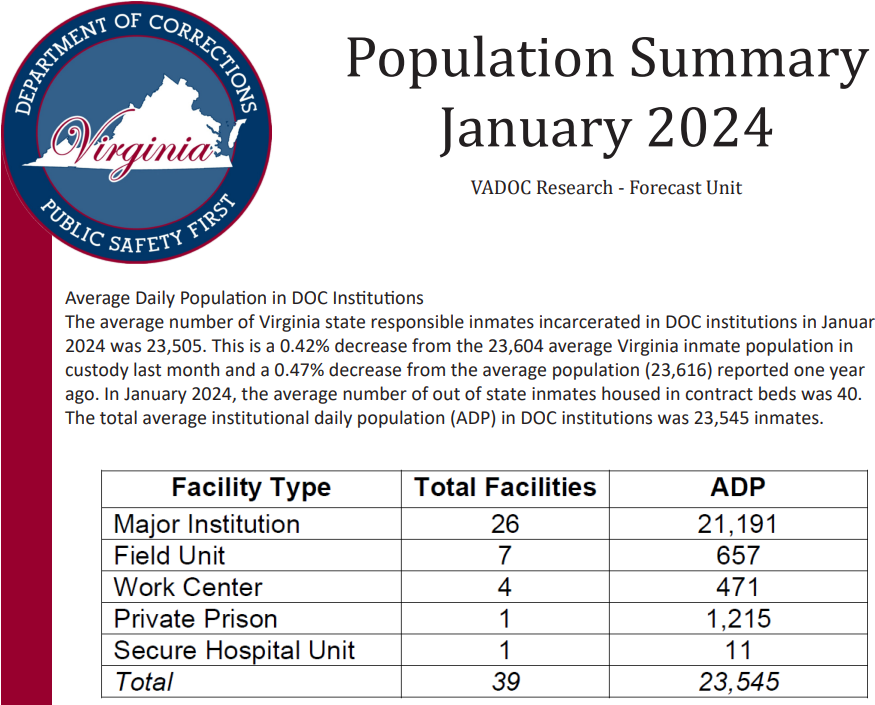

at the start of 2024, over 23,000 people were incarcerated in state-run facilities (in addition to those in local jails)

Source: Virginia Department of Corrections, Population Summary January 2024

The surge of prison capacity in the 1990's created more jail cells faster than Virginia judges created prisoners. The excess capacity in modern prisons was created in part by a lower-than-expected crime rate. Project Exile and other deterrents my have been effective, or perhaps the aging population was less inclined to commit crimes (or smarter about not getting caught...). The good economy in the "dot com" boom may have made it easier to earn money than to steal it, or perhaps Virginia failed to catch the first crooks that shifted to e-crime.

Other states, which had the opposite situation, contracted with Virginia to house their inmates. New Mexico, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia were the most visible in this rent-a-cell program. This generated revenue for Virginia, and met the needs of the states that had exceeded population capacity of their jails.

The "supermax" prisons are located in Southwest Virginia, where the local demographics are substantially different from urban areas. As a result, the diversity of the guard force does not match the racial patterns of the criminal population in the facility. Out-of-state legislators have nothing to lose by blaming Virginia's correctional officers whenever an inmate from their region is injured or dies in a Virginia jail, and even suggesting racial bias. (Connecticut had its prisoners moved to the Greensville Correctional Center in 2001, before returning them all to Connecticut in 2004.)

The warden at Wallens Ridge State Prison filed suit against New Haven, Connecticut newspapers after they portrayed him unfavorably in articles about treatment of the Connecticut prisoners. As described in a 2002 appeals court decision:2

A District Court had ruled that "the defendants' Connecticut-based Internet activities constituted an act leading to an injury to the plaintiff in Virginia" because "the newspapers understood that their defamatory articles, which were available to Virginia residents on the Internet, would expose Young to public hatred, contempt, and ridicule in Virginia, where he lived and worked.... The defendants were all well aware of the fact that the plaintiff was employed as a warden within the Virginia correctional system and resided in Virginia," and "...any harm suffered by Young from the circulation of these articles on the Internet would primarily occur in Virginia."

However, the appeals court dismissed the suit, ruling that "newspapers do not have sufficient Internet contacts with Virginia to permit the district court to exercise specific jurisdiction over them."

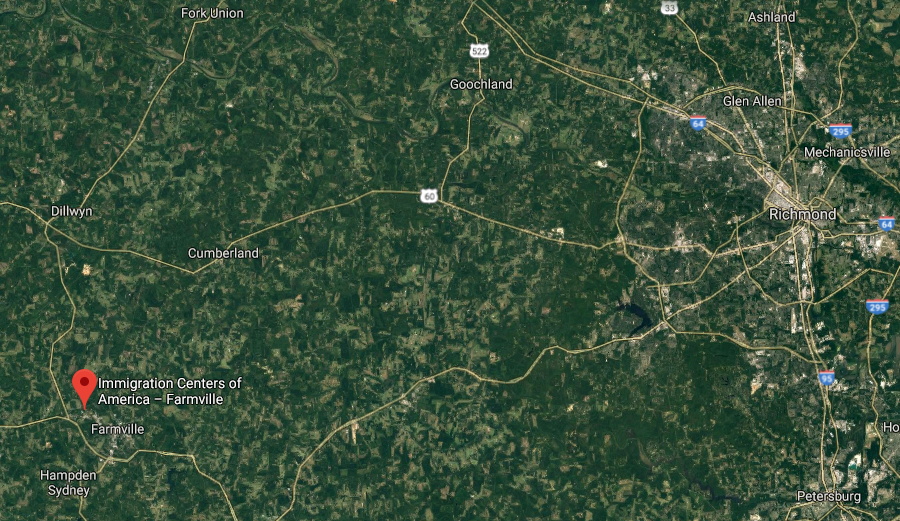

In 2009, a private, for-profit corporation (Immigration Centers of America) built the Farmville Detention Center in Prince Edward County, near the Piedmont Regional Juvenile Center. It contracted with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a Federal agency in the Department of Homeland Security, to house undocumented immigrants.

In 2018, the Department of Justice decided to stop keeping Federal inmates in private prisons, but the Department of Homeland Security did not mirror that decision and kept housing detainees at the Farmville Detention Center.

the Farmville Detention Center was built in 2009, and is located near the Piedmont Regional Juvenile Center in Prince Edward County

Source: GoogleMaps

Later in 2018, Immigration and Customs Enforcement arranged for a second facility in Virginia to house immigrants. The Peumansend Regional Jail had operated in in Caroline County between 1999-2017, housing overflow prisoners for the counties of Arlington, Caroline, Loudoun and Prince William plus the cities of Alexandria and Richmond. When the need for additional space declined, the prison closed and Caroline County ended up the only remaining member of the authority.

President Donald Trump announced in 2018 that all illegal immigrants would stay in detention rather than be released before trial, and that increased the demand for housing the immigrants. Immigration and Customs Enforcement planned to hire over 100 people, and pay Caroline County a minimum of $27,600 daily for five years. As part of the arrangements, the Peumansend Regional Jail was renamed the Caroline Detention Facility.3

The Federal agency planned to keep 336 people there. It guaranteed payment of $123.15/day per person for the first 224 detainees, $50.08/day for the next 55 people, and $22.08/day for the last 55 detainees. The average stay was expected to be 78 days, during which a person would go through the administrative hearing process and be deported or released.

Five buildings there were designated to house undocumented men, and one for women. Each room was scheduled to hold four detainees.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement did not plan for children to be kept at the site. The Caroline County site was not open during the 2018 furor over separating undocumented parents from their children.4

in 2018, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) contracted to use the former Peumansend Creek Regional Jail to house 336 undocumented immigrants

Source: Peumansend Creek Regional Jail

note the absence of state prison facilities in Northern Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Corrections