the Susan Constant was the first prison in Virginia, restraining John Smith until the colonists unloaded the vessel at Jamestown

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown National Historic Site

the Susan Constant was the first prison in Virginia, restraining John Smith until the colonists unloaded the vessel at Jamestown

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown National Historic Site

Long before the English colonists reached Virginia in 1607, they incarcerated their first prisoner - John Smith. He was too outspoken during the beginnings of the journey from London to Virginia. After the three-vessel expedition resupplied at the Canary Islands, the other leaders of the expedition accused Smith of mutiny.

Smith wrote later that he was "restrained as a prisoner" for the last 13 weeks of the trip from the Canary Islands, so the first prison in Virginia was a cabin on the Susan Constant as it sailed into the Chesapeake Bay. In the close quarters of the ships during an ocean journey, "restraint" may have consisted of a loss of status and shunning by the leaders who had tired of hearing his advice, but he could have been shackled in a cabin. According to Smith, he was able to communicate to others on the ship that he was being treated unfairly.1

After arriving in the New World, the unhappy leaders did not mellow in their attitude towards John Smith. Captain Christopher Newport decided to hang Smith when the three ships reached the island of Nevis. Smith reported with wry understatement later that:2

Smith may owe his life to the intercession of other leaders on the journey. Captain Christopher Newport had been given exclusive command during the trip across the Atlantic Ocean, and while on Nevis no one knew who would be appointed to the Council that would govern once the colony was established, but key leaders such as Bartholomew Gosnold must have known that Smith had been recruited by the Virginia Company of London for his military skills. Newport had the authority as sole leader during the ocean journey phase to execute a mutineer, but was evidently persuaded to show mercy.3

Smith remained estranged from the other colonial leaders in Virginia until June 10, when he was finally released from the Susan Constant, the first prison in Virginia. Smith was given the seat on the council assigned to him in the instructions that had been prepared by the Virginia Company in London in 1606.

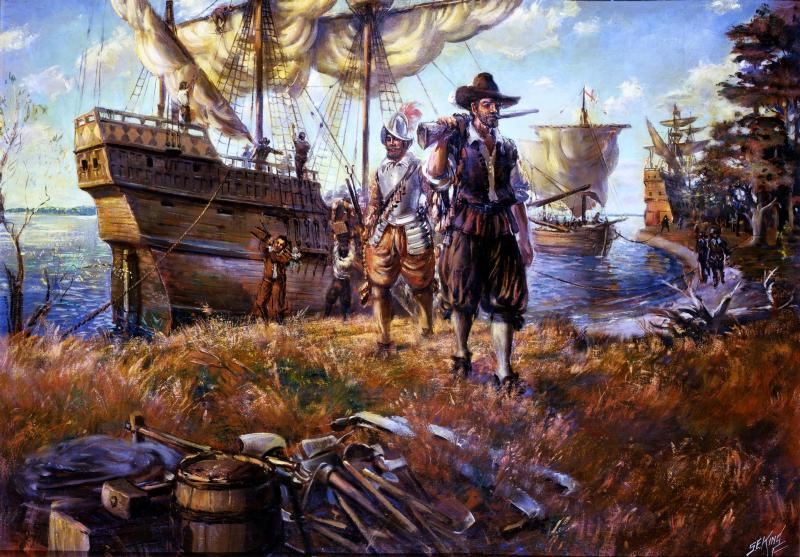

On June 22, Christopher Newport took the Susan Constant back to England, and the Godspeed accompanied him. The smallest vessel, the pinnace Discovery, was left behind in Virginia. It ended up as the second prison in the colony.

the first two prisons in Virginia were the ships Susan Constant and Discovery

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, Colonists Landing at Jamestowne

Christopher Newport was able to command authority while in Virginia. After he sailed back to England, president of the council Edward Maria Wingfield and the members of the council were in constant conflict with each other. Captain George Kendall may have been a prime agitator, seeking to add his ally George Archer as an official member of the council.

For unstated crimes described just as "hainous matters," the council removed Captain George Kendall from his leadership role and placed him under arrest sometime before September, 1607:4

Kendall was expelled from the council and placed under arrest, but classifying him as a political prisoner may not be appropriate. The arguments between John Smith and others on the council must have been blunt and heated, perhaps more so than arguments between the "gentlemen" president and councillors who understood the social graces of the times, but it was George Kendall who was arrested.

If his unacceptable behavior involved another person, no one else was accused. His crime was undocumented and remains unknown.

Arresting Kendall required the colony to have a secure facility, and there were no such buildings within the fort at Jamestown. John Smith noted that in September, 1607:5

The solution was to place Kendall in a locked cabin on the Discovery. That ship was about the size of a modern singlewide house trailer, and evidently had at least one cabin that could be used as a jail cell.

a copy of the Discovery, the second prison in Virginia, was created by the state of Virginia for the 350th anniversary of Jamestown in 1957

Forcing George Kendall off the council reduced the leadership team at Jamestown to four members by September, 1607. Captain Christopher Newport had sailed back to England, and Bartholomew Gosnold had died. Though smaller, the council remained a hostile working environment.

On September 10, the three council members (John Ratcliffe, John Smith and Captain John Martin) rebelled against president Edward Maria Wingfield and deposed him from the office of president. John Ratcliffe, captain of the Discovery on the initial journey from London, was elected as the new president.

The council placed Wingfield under arrest and on September 11 conducted the first formal trial in Virginia using English procedures, up to a point. His request for written articles detailing the charges was rejected, and there as never a real possibility that the three mem who had arrested the president of the council would deliver a verdict of innocent.

The council incarcerated Edward Maria Wingfield on the Discovery. To make room, they released George Kendall from confinement on the ship.6

John Smith had planned to use that ship to sail to nearby towns of local tribes and obtain corn. He ended up using smaller barges instead, so Wingfield did not have to be transferred to confinement on land. Wingfield remained imprisoned on the ship until Captain Newport arrived with the First Supply in early January, 1608 and ordered him to be freed. Wingfield finally left Jamestown in April, 1608 when Newport returned to England.7

After deposing Wingfield, John Ratcliffe was the new president of the council but he found it difficult to command respect from other colonists. When he was abusive to James Read, a blacksmith in Jamestown, that man responded with a threat to hit Ratcliffe. The new president made an example of his authority, and had the council try the blacksmith and condemned him to death. That process was perhaps the second jury trial following English procedures in Virginia, and the verdict must have been equally unsurprising as the verdict against Wingfield.

The blacksmith was incarcerated briefly, perhaps in a storehouse that had been erected inside the fort during the earliest stages of settlement. Some building may have been used as the colony's first, de facto prison on land in 1607, while a cabin on the Discovery was reserved for a prisoner of higher status such as Wingfield.

A gallows was erected to hang the blacksmith, but he used a creative maneuver to save his life. Just before being hung, the condemned man accused George Kendall of being a spy for the Spanish. Instead of hanging the blacksmith, president John Ratcliffe and the two members of the council (John Martin and John Smith) tried Kendall, declared him guilty, and had him executed in November 1607. It is unclear if Kendall was confined on the Discovery or within the fort before his execution.

Kendall became the first Virginia colonist to experience the death penalty under English law. That harsh punishment reflected fears that Kendall might somehow escape and inform the Spanish of the weak condition of the colony, and the reality that there was no way to imprison people in Jamestown.8

Though Virginia Company leaders were able to lock up the blacksmith and Native Americans briefly on land and keep Wingfield/Kendall incarcerated on a ship, they were unable to keep colonists from wandering away from the fort or leaving the peninsula. Powhatan benefitted from colonists willing to trade supplies stolen from the Virginia Company storehouses, and from deserters who brought him intelligence, tools, and even weapons. The loss of supplies ended only after Smith placed a blockhouse to control passage across the narrow peninsula.9

In addition to arresting each other, the council did order the seizure of Native Americans and keep them within the walls of the fort at Jamestown. In the spring of 1608, the colonists were frustrated by steady pilfering items made of iron and copper, and by intermittent attacks on individuals or groups who left the safety of the fort. The English seized a dozen men one day, adding to four or five already being held as punishment for some sort of offenses.

In response, the Native Americans around the fort captured two men who had been gathering food. John Smith reacted by leading a force on the barge to various settlements along the James River, burning towns and destroying canoes. The English also separated the captives and fooled them into thinking their friends were being executed.

After three days, Powhatan sent messengers (including Pocahontas) to request the release of his men. The colonists let them go, thinking that the Native Americans had been intimidated sufficiently. The alternative was to execute the prisoners, or to whip them and let them go. There was no space in which to restrain them indefinitely, and not enough food to feed long-term prisoners. After the short imprisonment, the small-scale attacks stopped briefly.10

the palisade constructed for the fort at Jamestown enabled the colonists to incarcerate Native Americans briefly, but there was no jail within the fort intended to isolate prisoners

During the Starving Time in the winter of 1609-10, Virginia Company officials at Jamestown had to deal with murder and cannibalism. Punishment came quickly after recognition of the crime; there was no consideration of long-term incarcertation. George Percy, president of the council at the time, wrote:11

In 1610, Percy was faced with the challenge of incarcerating captured members of the Paspahegh tribe. That problem was solved by killing the prisoners, eliminating the need for using any structure as a prison.

Percy led an expedition against the Paspahegh tribe, living just upstream of Jamestown, after Sir Thomas Gates finally arrived from Bermuda and took charge of the colony. The English raiders captured several Paspahegh men, plus the queen and two children. The men were killed, but the queen and children were loaded on the boat to be carried back to Jamestown.

On the trip back downstream, the English threw the two children overboard into the James River and used them for target practice. Percy "had mutche to doe To save the quenes lyfe" and bring her alive to Jamestown.

Once there, Sir Thomas Gates decided he did not want her as a hostage. He directed that she should be burnt alive rather than kept alive as a prisoner requiring food and guards. Rather than follow the suggestion, Percy had the queen executed by sword thrusts. It may have been a more-humane technique than burning, but was equally effective in eliminating the need for a prison.12