The Basis for Local Government in Virginia vs. the Basis for the Federal Government

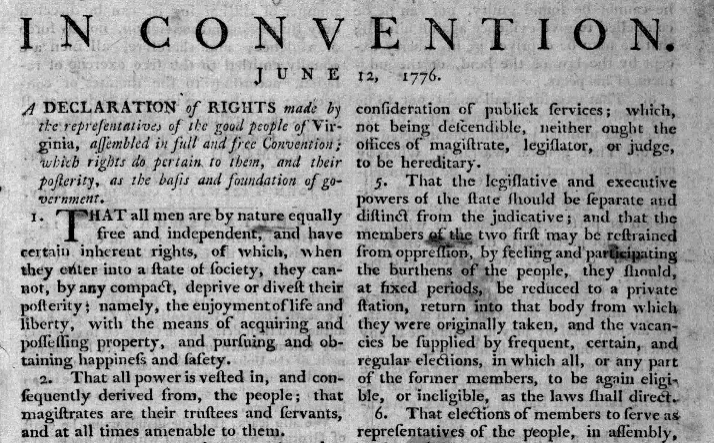

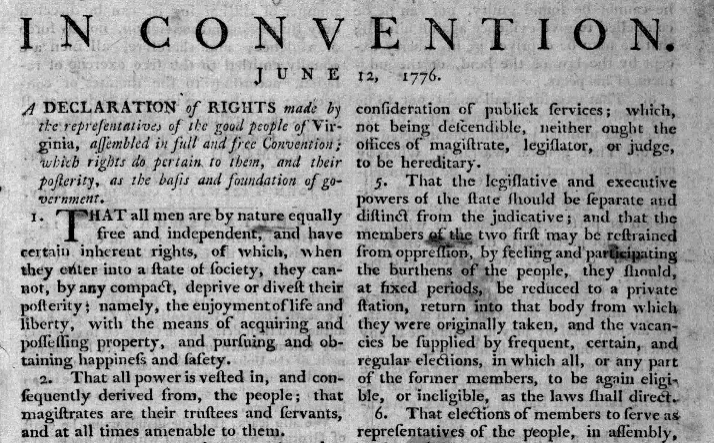

the June 12, 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights defined the basis for government authority: "all power is vested in, and consequently derived from the people"

Source: Library of Congress, In convention. June 12, 1776. A declaration of rights made by the representatives of the good people of Virginia

In 1776, the Fifth Virginia Convention declared independence and crafted the first state constitution. The convention claimed that the new state government inherited all the powers of the old colonial government, yet the new constitution eliminated the role of a king who had previously been considered the source of those powers.

Philosophically, the powers of the new Commonwealth of Virginia were based on a "bottom up" grant of the people rather than the old "top down" grant from the king of England. The convention adopted a Bill of Rights earlier on June 12, 1776, before voting on a constitution. In that Bill of Rights, Section 2 stated:1

- ...all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people...

Though authority flowed from the people, there was no vote by the people to ratify the first constitution. In the chaos the early days of the American Revolution, the Fifth Virginia Convention simply proclaimed the new constitution to be in effect. The role of British officials was eliminated, but the powers of the General Assembly were retained.

The people in Virginia have been defined as the source of authority for the state government since 1776. However, that basis should not be extrapolated to say that "the people" are the source of authority for 95 counties, 38 cities, and 191 towns in Virginia.

Local governments in Virginia get all of their authority to make decisions through laws passed by the state legislature, the General Assembly. The authority cited for splitting from King George III - and for the creation of the Federal government, "We the People..." - is not the authority for the creation of local government in Virginia.

Between 1619-1852, the legislature appointed all local officials, including the members of the county court and the sheriff. After 1619, white men could vote, but only for two people to represent them as burgesses in the Grand Assembly. When county courts were established and county boundaries formalized in 1634, no one could vote for local officials. All of the members of the county court were appointed by the governor.

Starting in 1670, the General Assembly added property requirements, limiting the right to vote to those who owned some form of real estate.

Patrick Henry's speeches in the House of Burgesses were heard by the only people elected by local voters

Source: Library of Congress, Stamp Act of 1765

Even after the General Assembly was modified with the 1776 state constitution, residents in Virginia's counties and towns still could not vote for the local officials who resolved legal disputes, collected taxes, authorized new ferries, set rates for taverns, and made so many other decisions that impacted local life.

The members of the General Assembly and the governors chose all of those local officials until a new state constitution went into effect in 1852. Today, the legislature still chooses the judges who serve in district and circuit courts.

Disestablishment of the Anglican church did increase the power of local voters. During the colonial era, the Anglican vestries were responsible for choosing ministers and for many local social welfare functions, such as making arrangements for the care of orphan children. The vestry imposed taxes upon county residents, comparable to taxes imposed by county courts for other local government expenses, to pay for the minister, building maintenance, and social welfare. Local residents could vote for their parish vestry just once, when the General Assembly created a new parish. After that initial election, only the vestry members chose new members to replace those who died or retired.

Government services performed by the Anglican vestries were transferred to county courts after 1776. Though local residents could not vote for members of the county court, they gained greater freedom in choosing the leadership of their local churches. Different denominations adopted different procedures for choosing leadership and ministers, reflecting both religious and political perspectives on the authority of an individual to make choices.

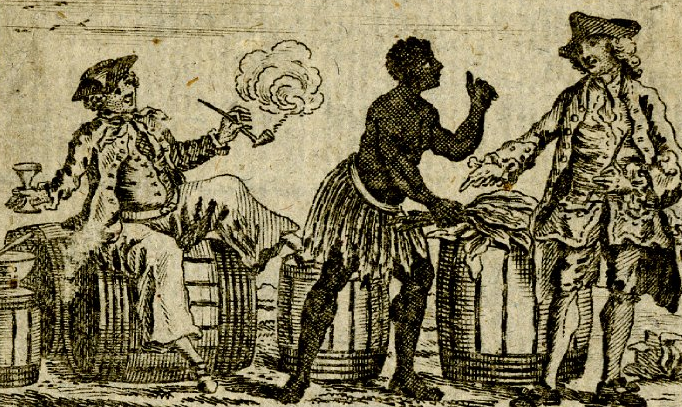

After 1776, the voting electorate was still restricted to a minority of Virginia residents. Only men could vote, and the 40% of Virginia men who were enslaved could not participate in the decision process. The burgesses revised George Mason's draft of the Virginia Bill of Rights before adopting it, in order to limit who could participate in the elections and making government decisions.

George Mason drafted the first version of the 1776 Declaration of Rights, but it was revised during debate in the House of Burgesses

Source: Library of Virginia, Adoption of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, oil painting

The final version limited who was entitled to "the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety." People had to first "enter into a state of society."

That phrase was designed to exclude slaves and prevent them from asserting the right to vote or seek other political rights. All governmental power might be "derived from the people," but not all people could participate in the governmental process.2

George Mason's draft of the Virginia Bill of Rights was edited in 1776 to ensure slaves could not cite that document and claim political rights

Source: British Museum, Newman's Best Virginia (tobacco label)

Today, most local officials are elected by local voters and not appointed by the General Assembly or governor. As a result, local government officials may be the ones who are most responsive to local priorities, but local voters can not increase the powers of local government on their own initiative.

Since 1776 the state constitution has granted all rights for government to the state. The General Assembly has delegated a portion of that authority to local towns, cities, counties, and regional authorities. Local governments have whatever powers were granted by the state legislature, not all powers based on a grant by the people.

The state government in Virginia was not created by local leaders who negotiated a contract that ceded only certain powers to the state and retained all other authority at the local level. There is no equivalent in the Constitution of Virginia to the US Constitution's Tenth Amendment along the lines of "all powers not granted to the state government are reserved to local cities/counties."

The Federal Constitution starts with "We the People of the United States... do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America," but prior to the Civil War politicians in Virginia argued that the Constitution was not a direct contract between all of the American people and the new Federal government. Instead, the US Constitution was a contract between the states, and that contract was ratified by 13 states rather than by a national referendum.

The leaders who met in Philadelphia in 1787 expected the new national government they created to resolve trade and tax issues that had blocked economic development after the American Revolution, but those leaders also feared the new national government would become too powerful. When asked to ratify the new Constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation in 1788, key Virginians such as Patrick Henry objected. Three of Virginia's representatives who participated in the 1787 Constitutional Convention (including George Mason) refused to sign the final version.

George Washington, depicted as standing at the table as the Constitution is signed, was key to adoption of a Federal government

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Signing of the Constitution (by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940)

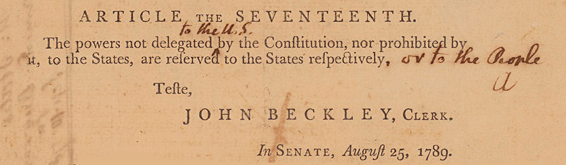

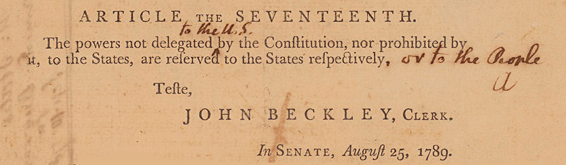

To soften the opposition, James Madison promised that a Bill of Rights would be added to the United States Constitution. The first nine amendments limited the power of the new Federal government, and the Tenth Amendment was expected to provide a final level of protection. It stated that the authority of the Federal government was limited to specifically-authorized purposes:3

- The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Of course, other clauses have been interpreted later to authorize broad powers now exercised by the US Congress, President, and Supreme Court. The "original intent" of the Founders continues to be debated in Supreme Court cases today, as states contend with the central government over which level of government has a specific authority.

what became the Tenth Amendment to the US Constitution (originally the 17th amendment proposed by the House of Representatives in 1789) limits the power of the Federal government, but there is no equivalent in the Constitution of Virginia limiting the authority of the state and reserving other powers to local governments

Source: National Archives, Senate Revisions to House-passed Amendments to the Constitution (draft of Bill of Rights), September 9, 1789

There are few questions regarding the power of the General Assembly regarding the local governments in Virginia. State courts have applied the Dillon Rule since 1896, making clear that local governments have no "home rule" powers. All power flows down from the state legislature. Virginia's cities, counties, and towns have no original authority, no powers granted directly by the people.

The General Assembly has defined "uniform charter powers" for all cities and towns, in Code of Virginia Section 15.2-1100 et seq. It has also established some clear authorities for counties.

Transportation planning has been controlled by the state since the General Assembly authorized the Little River Turnpike, and the Board of Public Works was finally created in 1813. Counties managed local roads until the 1932 Byrd Road Act centralized responsibility for road construction and maintenance at the state level. Though four counties were permitted to retain their authority, there was no question that the state legislature determined local authorities.

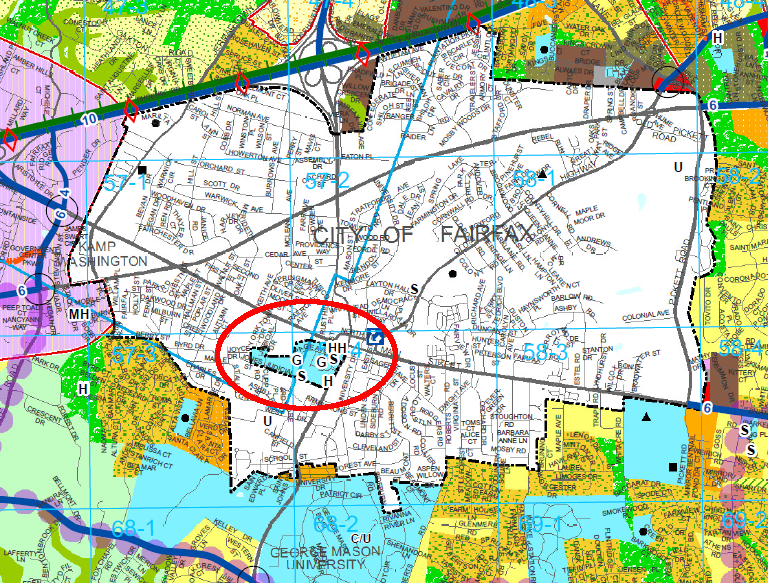

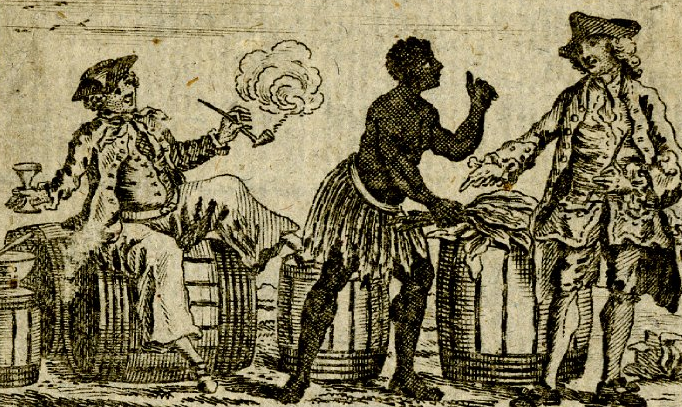

The General Assembly has given authority for land use planning and zoning to the separate local jurisdictions. The state did create 21 Planning District Commissions to facilitate regional coordination and the Federal government mandates regional planning for its transportation funding, but the General Assembly has not required that local jurisdictions coordinate their land use decisions.

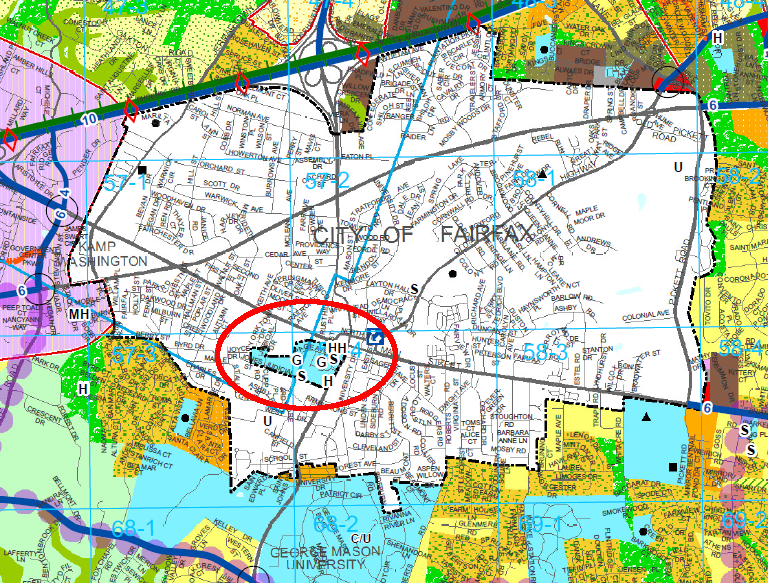

A small slice of one jurisdiction may be completely surrounded by another jurisdiction, but each city/county/town can ignore the planning of its neighbor. For example, Fairfax County determines the use of the Fairfax courthouse property, which is part of the county. The courthouse property is completely surrounded by the City of Fairfax, but the city has a separate long-range Comprehensive Plan and separate zoning categories. The city's plans and zoning do not define appropriate uses for the courthouse property, because it is within the county.

a small slice of Fairfax County is isolated within the boundaries of the City of Fairfax, comparable to a hole in a doughnut

Source: Fairfax County Comprehensive Plan

Arlington County has tested the ability of a local government to exert authority independent from the state government based in Richmond. In 2006, the General Assembly expanded the authority granted to localities for managing how vehicles are towed from private property, including parking spaces controlled by Home Owner Associations.

State code defined the membership of a localities' Trespass Towing Advisory Board to include only one member from the general public, along with three members from the local police department and three the towing industry. In 2016, Arlington County enlarged its local Trespass Towing Advisory Board with 10 more members to ensure public concerns about inappropriate towing practices were considered more fully.

The county also required a "second signature" from property owners just before cars could be towed from commercial property during business hours, generating opposition from the towing industry and Arlington Chamber of Commerce. In response, the state legislature passed HB 1960 to prohibit a second signature requirement and limit the membership on local Towing Advisory Boards.

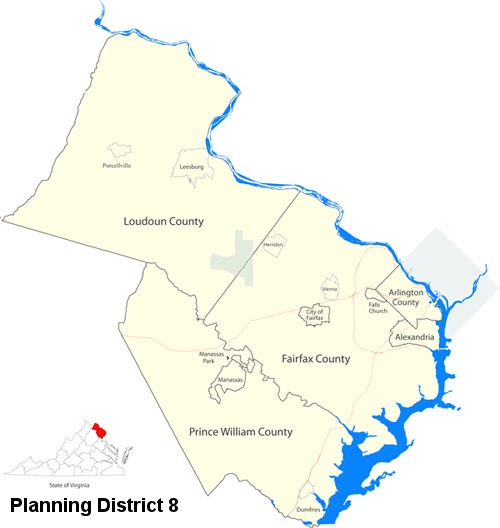

In a clear demonstration of the legislature's dominant position, law affected only local jurisdictions in Planning District 8 (Northern Virginia). The General Assembly allowed Virginia Beach and Stafford to keep their local ordinances, which included the second signature requirement.4

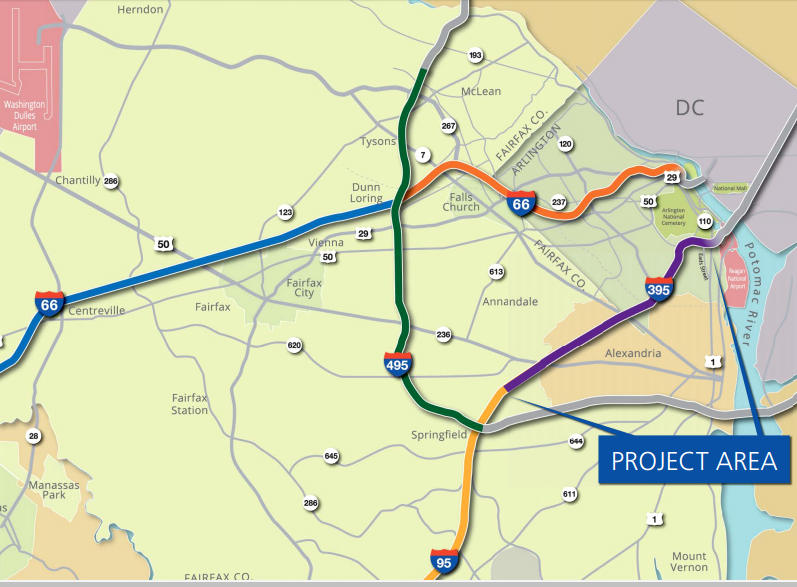

the General Assembly passed legislation in 2017 that limited the ability of localities in Planning District 8 to regulating the towing of cars from private property

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Northern Virginia Map

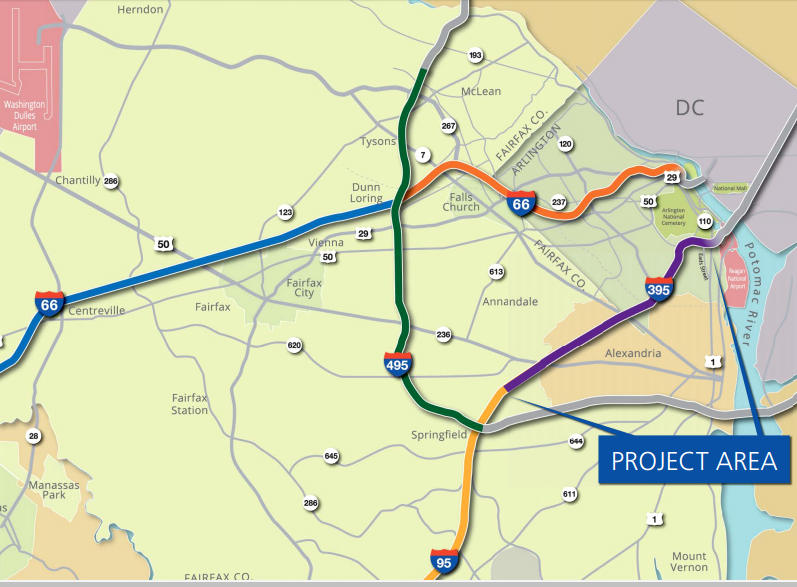

The targeted legislation reflected in part the General Assembly's frustration with Arlington County county's success in blocking creation of the High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes on I-95/I-395 to add another lane. The Virginia Secretary of Transportation had negotiated a deal with a private company, Transurban, to add the additional lane and convert the two existing High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes on I-95 between Garrisonville and the Potomac River into a toll road. Arlington County sued in 2009, claiming the Federal Highway Administration's environmental analysis was inadequate.

Rather than delay the project, Virginia and Transurban truncated the project at Eads Road just north of the I-495 Beltway. It took another six years to negotiate a deal to widen the highway and extend the HOT lanes all the way to the 14th Street Bridge across the Potomac River.

At the time, the General Assembly was controlled by Republicans who were not in sympathy with the heavily-Democratic "Peoples Republic of Arlington." In a move widely interpreted as retaliation, the General Assembly refused to re-authorize a 0.25% hotel tax surcharge imposed by Arlington. The loss of that extra tax reduced the city's funding for tourism promotion by $1 million/year. When the surcharge renewal was considered, the Republican chair of the subcommittee suggested Arlington County could have used for tourism the money spent on the lawsuit to block the HOT lanes:5

- If they've got so much money for silly, abusive, intimidating, frivolous lawsuits like this, then they obviously have plenty of cash in Arlington and don't need this tax reauthorized.

Arlington County delayed extension of High Occupancy Toll (HOT) Lanes to the Potomac River in 2009, but the project (section colored purple) was finally approved in 2015

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, I-395 Express Lanes Extension - Display Boards (Design Public Hearings were held October 24, October 26 and November 30, 2016)

Links

References

1. "Virginia's Declaration of Rights (1776)," Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, https://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/270/ (last checked August 24, 2017)

2. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights, June 12, 1776," Library of Virginia, http://edu.lva.virginia.gov/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/doc/declaration_rights (last checked August 24, 2017)

3. "US Constitution," National Archives, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_transcript.html (last checked February 18, 2015)

4. "County Board Agenda Item Meeting of February 22, 2014," Staff report on Amendments to the County's towing ordinance, Chapter 14.3 of the Arlington County Code, February 10, 2014, http://arlington.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=2726&meta_id=118159; "Arlington County Board Approves Towing Changes, Despite Some Business Opposition," ARLnow, December 14, 2016, https://www.arlnow.com/2016/12/14/arlington-county-board-approves-towing-changes-despite-some-business-opposition/; "HB 1960 Tow truck drivers and towing and recovery operators; civil penalty for improper towing," Legislative Information System, Virginia General Assembly, 2017 Session, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?ses=171&typ=bil&val=hb1960; "McAuliffe Signs Bill Overriding County's Towing Changes," ARLnow, April 26, 2017, https://www.arlnow.com/2017/04/26/mcauliffe-signs-bill-overriding-countys-towing-changes/ (last checked September 21, 2017)

5. "Virginia to extend I-95/395 HOT lanes north to D.C. line," Washington Post, November 20, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/dr-gridlock/wp/2015/11/20/virginia-to-extend-i-95395-hot-lanes-north-to-d-c-line/?utm_term=.59a95b88218e; "Richmond Bites Back on HOT Lanes Suit By Blocking Tax Bill," ARLnow.com, January 21, 2011, https://www.arlnow.com/2011/01/21/richmond-bites-back-on-hot-lanes-by-blocking-tax-bill/ (last checked September 21, 2017)

Virginia Government and Virginia Politics

Virginia Places