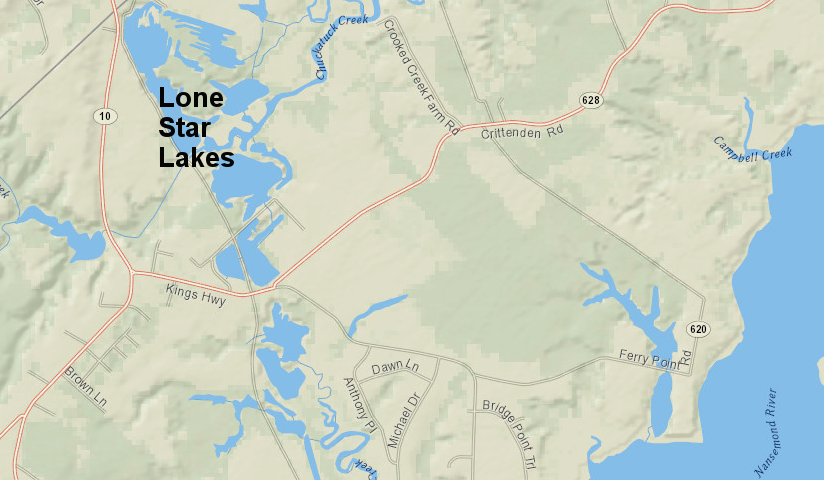

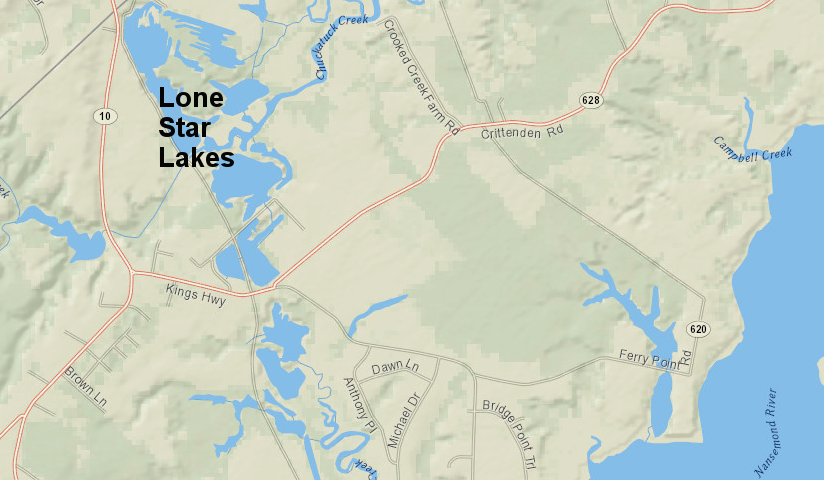

Lone Star Lakes Park in the City of Suffolk marks where marl was excavated for 50 years

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lone Star Lakes Park in the City of Suffolk marks where marl was excavated for 50 years

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In Delaware, New Jersey and New York, "marl" refers to Cretaceous Period sediments also known as "greendsands." They are rich in glauconite, a potassium, iron, aluminum silicate derived roiginally from the fecal pellets of marine organisms. Beds of greensands in the Middle Atlantic states may not include a signifcant amount of calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

Farmers near Marlboro, New Jersey, recognized the value of greensand to improve crop yield starting in 1768. The value of adding potassium to the soil was determined by Professor William B. Rogers at the College of William and Mary in 1835.

Greensands in Virginia also are enriched with calcium. It was added by shells on the ocean floor among which the fecal pellets accumulated. Edmund Ruffin studied agricultural chemistry in hopes of restoring the fertility of old tobacco fields, and is credited with the discovery of a greensand deposit in 1818. Ruffin became a well-known agriculturalist and published An Essay on Calcareous Manures in 1832.

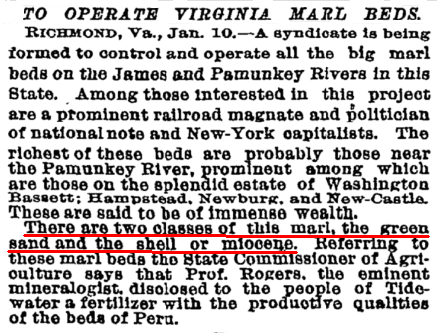

Until the 1850's, marl was dug up along the James, Pamunkey, Mattapony, and Rappahannock rivers and spread by enslaved laborers on farm fields. "Marling" was thought to improve crop yields for a decade or more. Before the Civil War, less-expensive and more-concentrated guano from Chile and potash fertilizer from Germany outcompeted Virginia marl.1

An advocate for using marl as a soil amendment and fertilizer wrote:2

greensands in Virginia include the mineral glauconite (a potassium, iron, aluminum silicate) plus calcium carbonate

Source: TimesMachine New York Times (Jan. 11, 1891)

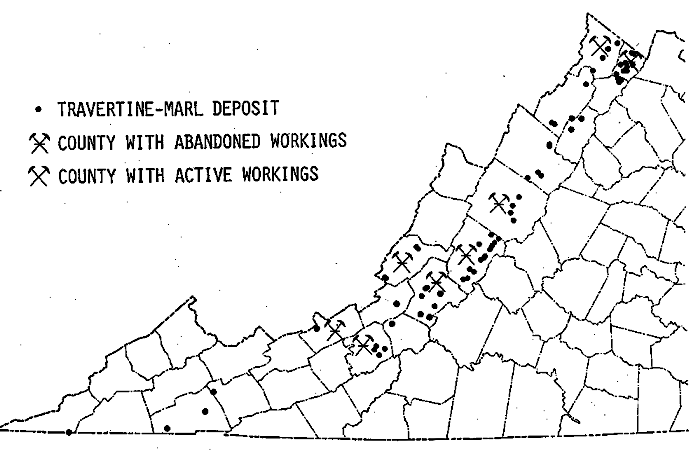

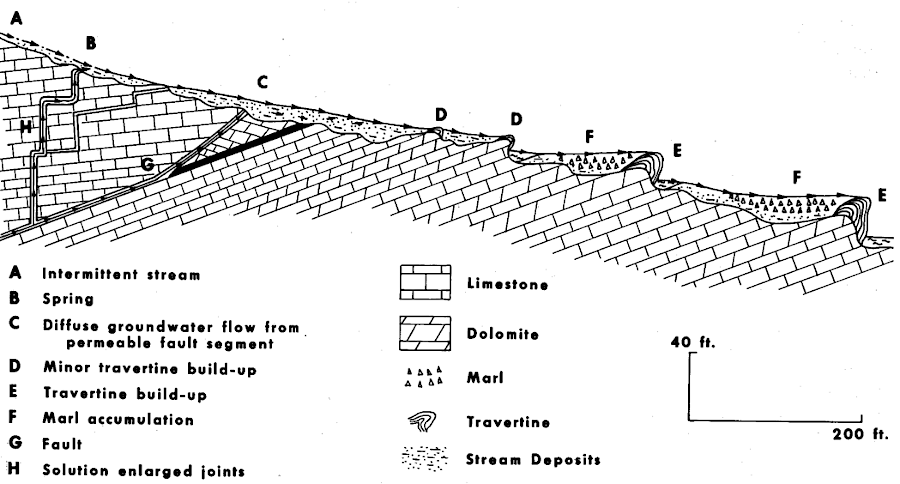

West of the Blue Ridge, marl deposits were formed in the Quaternary Period from calcium that leached out of Paleozoic Era limestone formations and was deposited near freshwater springs. Travertine and marl have been identified in 57 streams within 17 western counties:3

marl deposits west of the Blue Ridge are from freshwater springs, unlike marine deposits on the Coastal Plain

Source: Virginia Minerals, Travertine-Marl Deposits of the Valley and Ridge Province of Virginia - A Preliminary Report (February 1985. Figure 4 and Figure 5)

Calcium-rich marl in Southeastern Virginia comes from a sedimentary bed of shells, or coquina, in the Yorktown Formation that accumulated in the Pliocene Epoch about three million years ago. Within the Yorkown Formation in Virginia, some of the shells once grew on shallow bars on the continental shelf in the Atlantic Ocean. Sea levels were higher 5-10 million years ago during the Late Miocene epoch, and the shoreline was further west at the line of the Suffolk Scarp. A precursor to the James River also carried broken shell fragments down to the bars in the warm waters of the estuary.

During the Pliocene:4

Sediments deposited in the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs on top of the Yorktown Formation were later stripped off by erosion, exposing the coquina bars at the surface.

At the northern end of the coquina beds near Yorktown, the Jamestown Portland Cement Corporation mined coquina beds that were as much as 15 feet thick from the bluffs along the York River. The material there was 75-85% calcium carbonate. The Colonial Portland Cement Corporation owned beds as much as 30 feet thick on the James River at the community of Grove, southeast of Williamsburg near the Carters Grove plantation.5

From 1929-1971, marl was mined in Nansemond County, from the Nansemond River ultimately past Chuckatuck to the Isle of Wight County line. Prior to 1924 acquisition of the land by a cement company, sisters Annie and Lucy Upshur mined the marl for use in chicken feed, fertilizer and even driveway construction.6

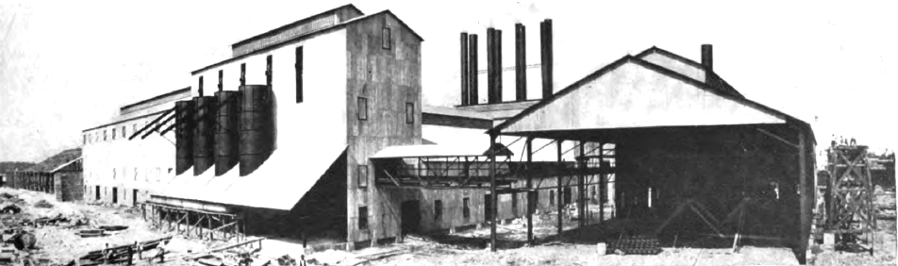

The raw material was floated by barge to South Norfolk and heated in furnaces there. The American Cement Company built the furnaces on the Elizabeth River, opposite the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, to produce Portland cement. It used marl instead of hard limestone bedrock as the source of the calcium, and was built after shipping marl to the company's existing plant in Pennsylvania to prove the resulting cement would meet the company's standards. The Portland cement, a mixture of silica from local clay and calcium from local marl, was shipped to customers via barge and via the Norfolk & Portsmouth Belt Line.7

a plant in Norfolk, built in the 1920's, transformed marl mined in Nansemond County (now City of Suffolk) into Portland cement

Source: Cement Age, New Portland Cement Plant at Norfolk, Virginia (p.91)

The potential of using marl from the Nansemond River region to fertilize the soil, and even to make cement, was recognized a century before the American Cement Company completed its plant in South Norfolk.8

The cement companies wanted to built plants closer to their customers in the South as the region began to industrialize after World War I, but there were no outcrops of limestone bedrock in Tidewater where ships could distribute the cement to customers. In Virginia, the closest outcrops were in Loudoun County.

Limestone sediments near Cumberland Gap were economic to develop because coal for heating the furnaces was nearby. The coquina beds near the mouths of the James River and York River were used as raw material primarily because transportation costs were so low. A 1913 report from the US Geological Survey noted:9

marl was mined from beds on the surface, then excavated from pits that later became recreational lakes

Source: Cement Age, New Portland Cement Plant at Norfolk, Virginia (p.91)

At the mining site, a drag line excavated blue mud from the creekbeds and the narrow (1 mile wide and 5 miles long) vein of marl which had been deposited 35 million years ago. The electrically-powered drag line could excavate marl from as much as 90-120 feet deep. When the rock was so hard the drag line bucket could not scrape it free, dynamite was dropped down to the bottom of the pit. Observers later commented that the resulting geyers were "better than any Disney ride."

The marl was loaded into cars pulled slowly by coal-fired steam locomotives and then by diesels to the hammer mill and washer plant on the Nansemond River. Sand, clay, whale vertebra, and reportedly a fragment of a meteorite were removed before the crushed stone was transferred by conveyor belt to barges and carried to the furnaces in South Norfolk.

The marl pits filled with water and became swimming holes. Local children ignored the No Trespassing signs erected after one boy drowned and used the ponds for skinny dipping. One later reported to the Greater Chuckatuck Historical Foundation:10

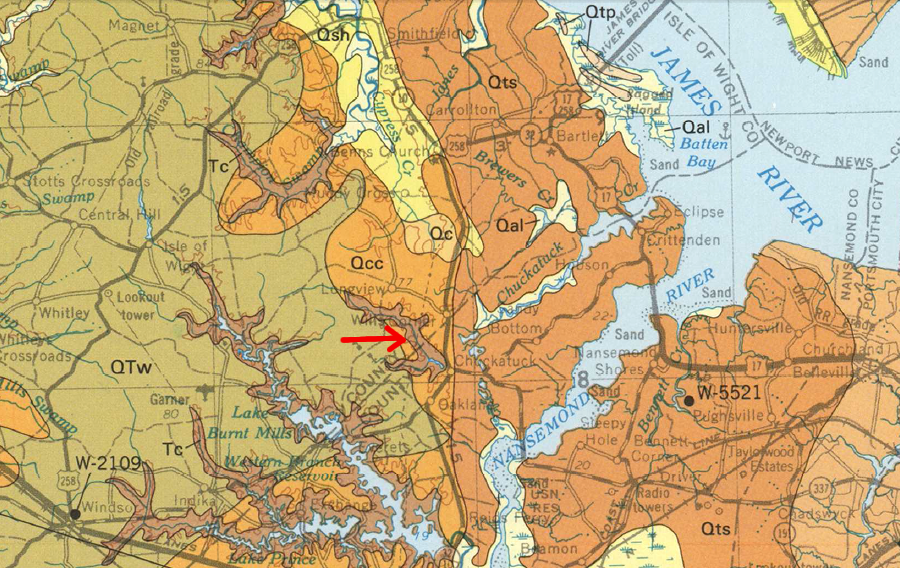

The mining site today is Lone Star Lakes Park, which is in the City of Suffolk after Nansemond County became a city in 1972 and then merged with the City of Suffolk in 1974.

Lone Star Lakes Park includes 12 lakes, some of which are interconnected. Water has filled 490 acres of pits excavated by the Lone Star Cement Company on Cedar Creek. Kings Highway, which leads to the park from Route 10, was the path of the railroad line that carried crushed marl to be loaded on barges on Chuckatuck Creek. Mining stopped in 1971, when the company chose not to upgrade the furnaces in order to meet air quality standards. The City of Suffolk then acquired the land, including the 11 mine spoil pits.11

coquina bars from the Yorktown Formation (see red arrow) were deposited in the Miocene epoch, and were mined for over 40 years

Source: US Geological Survey, Geologic map and generalized cross sections of the Coastal Plain and adjacent parts of the Piedmont, Virginia (1989)