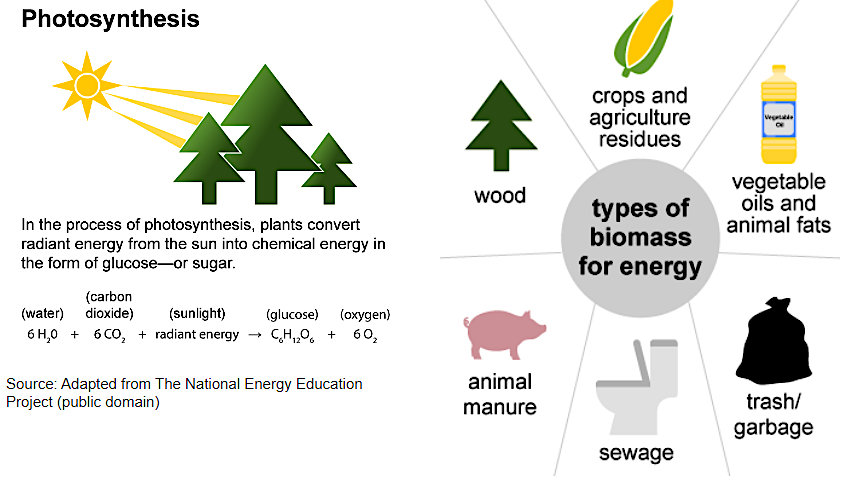

biomass captures solar energy, and releases it when burned

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Biomass, explained

biomass captures solar energy, and releases it when burned

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Biomass, explained

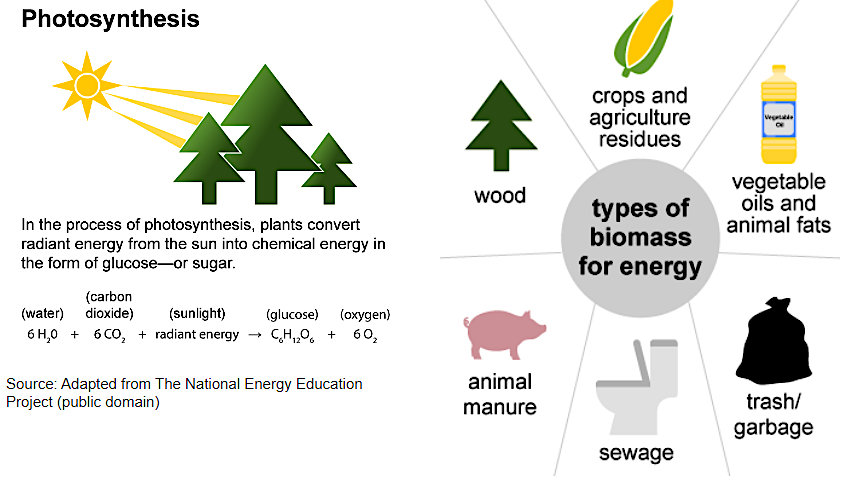

In 2020, the Environmental Protection Agency classified 32 electricity generating facilities in Virginia as being fueled at least in part by biomass. That number included power plants burning wood and "black liquor" from paper mills, waste-to-energy incinerators burning municipal solid waste, and landfills extracting methane for small generation operations.

In addition, other locations burned wood waste, corn stover, and switchgrass for heat. The Piedmont Geriatric Hospital switched from burning coal/sawdust to just switchgrass and installed a new boiler, after two trial runs in 2006-2007. Switchgrass, with 15% water content, was more cost-effective than sawdust with a 50% water content. That shift in fuel source created a local market around Nottoway County for local farmers to raise switchgrass with targets for high BTU content, rather than raise hay with targets for its nutrition content.

Source: US Department of Energy, Growing Bioeconomy Markets: Farm-to-Fuel in Southside Virginia

delivering switchgrass to the boiler at Piedmont Geriatric Hospital

Source: FDC Enterprises, Harvesting Switchgrass for Biomass

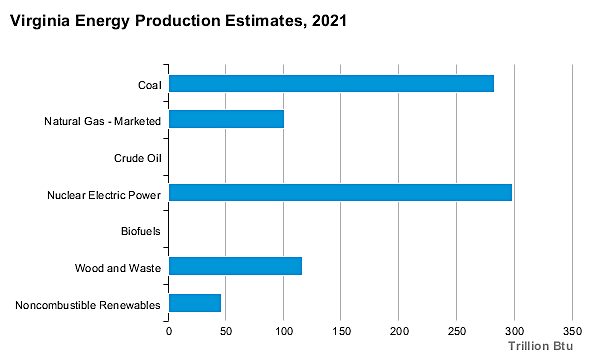

In 2021, 4% of the electricity generated within Virginia came from biomass facilities. Of that total, about two-thirds came from facilities that use wood and wood waste and one-third from municipal solid waste and landfill gas. Solar generated another 4%, coal about 4%, and conventional hydroelectric plants about 2%. Natural gas and nuclear provided the remainder.

In 2023, Virginia's consumption of biomass was #3 in the nation behind Georgia and Alabama, and ahead of California and Louisiana. The rankings reflected the availability of waste material from wood processing facilities.1

in 2021, there were 30 biomass facilities in Virginia generating electricity from municipal solid waste, landfill gas, black liquor, and wood

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Emissions & Generation Resource Integrated Database (eGRID 2021)

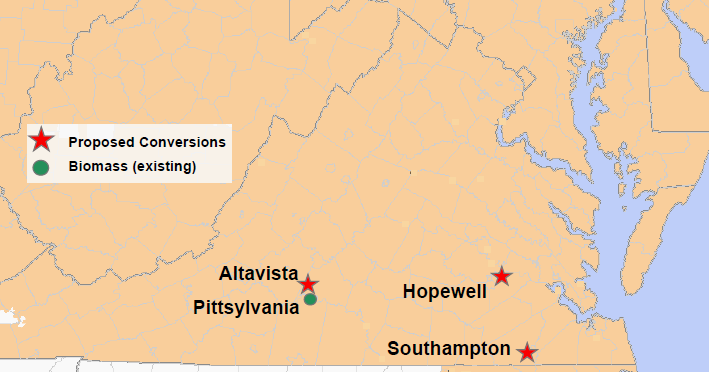

Virginia has several facilities that generate electricity by burning waste wood from timber operations, particularly Dominion Energy power plants in Altavista, Hopewell, and Southampton that formerly burned coal. The shift in fuel resulted in the stations dropping from 63MW of generation to 51MW.2

The primary renewable resource be used as fuel is wood. Biomass companies planned to process sawmill residue and forest "slash." The waste wood was low-cost residue, available for primarily the cost of hauling to a processing plant. In theory, biomass facilities would not use many pine or hardwood tree trunks which could be converted into profitable lumber, veneer or paper.

Slash consists of portions of trees (such as branches and tops) that are not suitable for conversion into lumber or furniture, and are not close enough to a mill to chop into wood chips. In addition, Virginia plants also process wood into pellets exported to Europe, where they are burned to meet European Union mandates for generating electricity from renewable sources.

Utilities and pelletizing operations highlight how their operations provide jobs in rural areas of Virginia (as well as the Port of Chesapeake), and cite how forests are a renewable resource for energy in contrast to traditional fossil fuels - oil, gas, and coal. Environmental groups have raised concerns that the demand for biomass to generate electricity in Virginia (or Europe) could spur excessive logging, beyond sustainable levels and beyond the processing of just "waste wood." A particular concern is the harvest of whole trees for biomass operations, in addition to the removal from forests of logging residue normally left on the ground to rot.

artist's depiction of South Boston Biomass plant, and aerial view after completion

Source: NOVI Energy and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2013, the Northern Virginia Electric Cooperative (NOVEC) opened the 50MW Halifax County Biomass (HCB) power plant in Halifax County, using fuel supplied by timber operations within 75 miles. Waste is chipped first before loading into the facility, so the fuel will burn smoothly. The heat then converts water into steam that turns a rotor in a generator and produces electricity, just as in a coal-fired power plant.

The plant also utilizes trees and brush collected as waste by the South Boston Department of Public Utilities and formerly burned in open pits. Wood dust and other waste from the Ikea furniture plant in Danville was another potential fuel source for the Halifax plant, but that facility closed in 2019.3

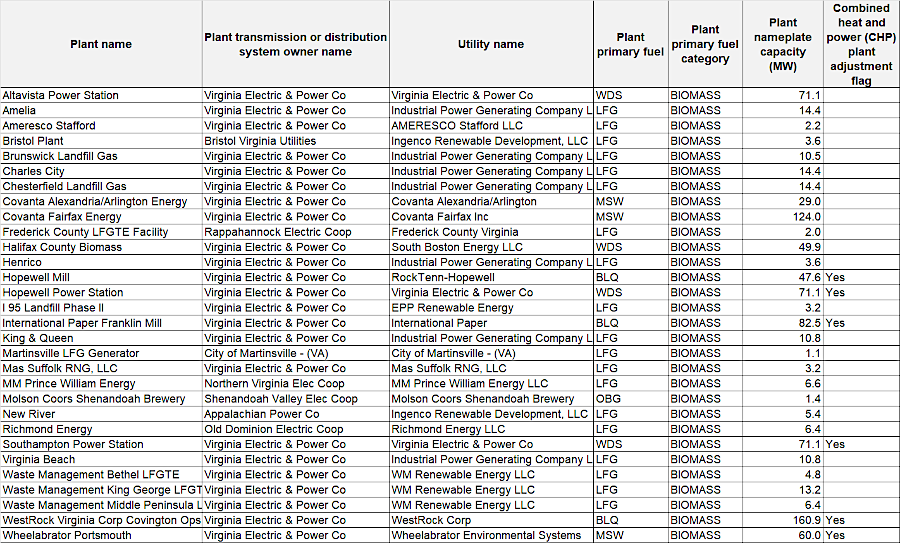

in 2020, the Energy Information Administration mapped landfill gas facilities as biomass operations

Source: US Energy Atlas, Biomass Energy Infrastructure and Resources

The NOVEC utility considers electricity generated from biomass to be carbon-neutral "green energy." Unlike power plants burning coal or natural gas (or vehicles burning gasoline/diesel/jet fuel), the CO2 emitted up the South Boston Energy smokestack would enter the atmosphere anyway as bacteria/fungi decomposed the slash on the forest floor. In a reflection of sustainable design principles, for cooling purposes the facility also used graywater from South Boston's wastewater treatment plant.4

The biomass plant was initiated after a Georgia Pacific plant closed in the Halifax County Industrial Park and local officials sought new economic development. With strong local support, an entrepreneurial company (NOVI Energy) developed a plan, obtained permits and a $3 million grant from the Virginia Tobacco Commission to subsidize the project. That company ultimately sold the facility to NOVEC.The electric cooperative has customers only in Northern Virginia, far from the Halifax County Biomass plant. No electrons actually flow from Halifax to Northern Virginia. As electricity enters the grid in Halifax, NOVEC draws equivalent amounts of electricity from the grid on the other side of the state.

NOVEC sells Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) to environmentally-conscious customers. The utility's advertisement clarify that the actual electricity being used in Northern Virginia does not come from the biomass plant:5

pattern of field and forest near Altavista, south of Staunton (Roanoke) River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Altavista 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013, Revision 1)

In Altavista, Dominion claims the Pittsylvania Power Station is "one of the largest biomass power stations on the East Coast." Each day, the plant is supplied with roughly 150 truckloads of wood chips by MeadWestvaco. Because wood chips contains less sulfur than coal, the utility highlights the low-sulfur emissions as well as the carbon-neutral character of the plant.6

The largest utility in Virginia, Dominion, also operates the power plant with the greatest opportunity for conversion of biomass into electricity. The 600MW Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County is "hybrid" because it can generate as much as 20% of its output from locally-grown wood/wood waste.

The fluidized bed boiler design allows use of low-quality wood or waste coal, which generate far less heat per unit of volume compared to the bituminous coal normally used in power plants. There are technical challenges in creating a steady flow of heat and steam when burning coal with high heat content and wood chips at the same time, but the biomass creates less residual ash than the coal.7

trucks deliver wood chips to the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center

Source: Dominion, Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center

The air quality permit was the last hurdle for opponents to try to block that plant from going into operations, and the final permit requires at least 5-10% of the electricity to come from biomass. In response to concerns that the power plant would spur excessive timber harvesting, Dominion responded with a claim that burning biomass would increase forest health:8

Dominion converted three coal-fired power plants to use exclusively wood waste for fuel, comparable to its larger facility in Hurt

Source: Dominion, Dominion's Planned Conversions from Coal to Biomass Power (2011 Powerpoint presentation)

Dominion Energy converted three 63MW coal-fired power plants at Altavista, Hopewell, and Southampton from coal, creating 51MW plants powered by waste wood biomass. The plants had been constructed to produce steam for adjacent manufacturing plants, and co-generated electricity as a byproduct. The utility could have upgraded the plants to meet Clean Air Act standards or closed the small facilities completely, but chose instead to create three renewable-fuel operations.9

The Altavista plant, like Dominion's biomass facility in Hurt, gets its wood chips from MeadWestvaco. That company harvests timber in the region to supply its paper mill in Covington. Dominion's 51MW renewable power plants are supplied with wood pellets manufactured by a separate company, Enviva. Because the Hopewell and Southampton plants are located closer to the ports in Hampton Roads, Enviva also has the option of shipping its wood pellets overseas.10

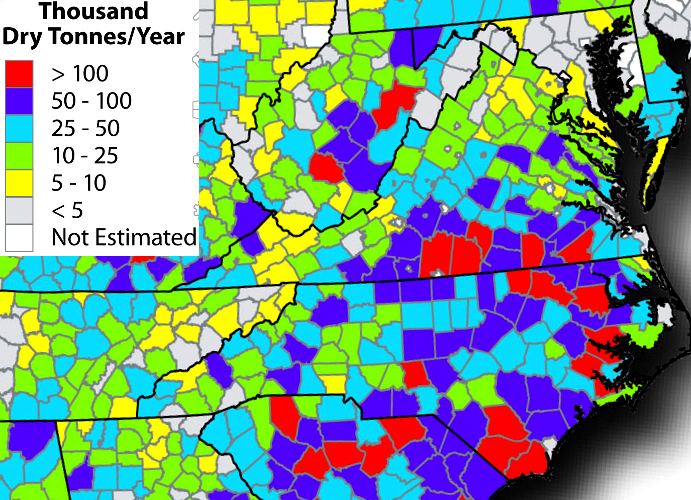

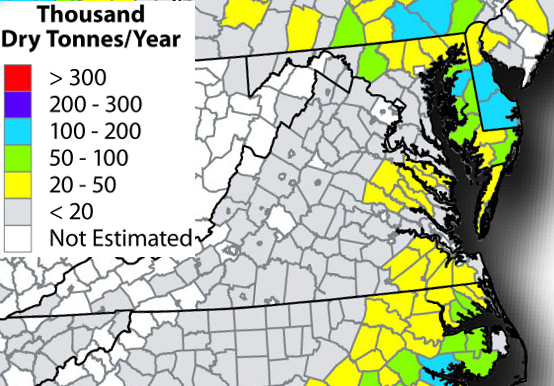

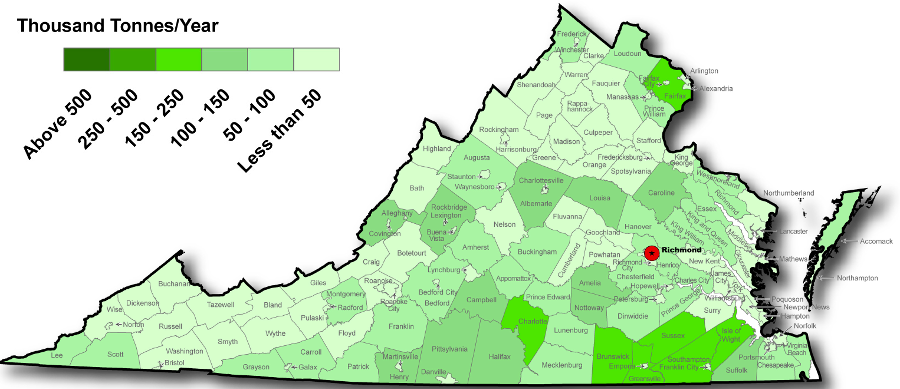

Southside Virginia, especially the Roanoke River basin, has the greatest potential to provide logging residues for biomass energy

Source: US Department of Energy - National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Forest residues

European Union regulations require use of renewable energy sources for generating electricity, so there is a strong market for shipping wood pellets from Virginia across the Atlantic Ocean. A wood processing plant in Louisa County could manufacture compressed wood pellets, ship them overseas from a terminal in the city of Chesapeake, make a profit despite the low energy value in the pellets and the high transportation costs - and regulators could consider the final product to be a form of green energy.

Such a deal was announced in 2011, though later that year the proposed production site shifted from a mill in Bumpass (Louisa County) to the Turner Tract Industrial Park in Courtland (Southampton County). The Bumpass plant, owned by Biomass Energy, closed in 2013. The Southampton County plant opened in 2015, ending up with the capacity to produce 760,000 tons of wood pellets per year.11

logs stockpiled at the Enviva plant in Southampton County for processing into wood pellets

Source: GoogleMaps

European utilities increased the percentage of their electricity coming from renewable sources by prioritizing wood pellets. By 2022, wood was Europe’s largest renewable energy source. Burning it avoided Europe's carbon tax and earned renewable fuel credits in that highly-regulated energy market.

Since there was no way to ship electricity directly to Europe, the United States could contribute to Europe's shift to renewable energy by shipping wood pellets instead of coal from Hampton Roads. However, the carbon neutrality of manufacturing the pellets in North Carlina and Virginia and shipping them to Europe were questionable.

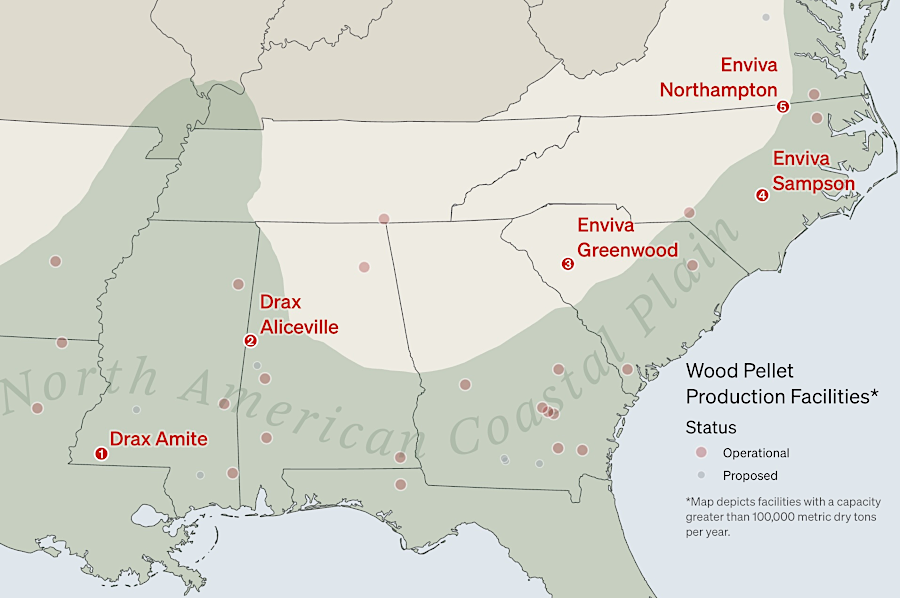

The Dogwood Alliance highlighted that burning wood increased carbon dioxide emissions now, while tree regrowth required decades to offset the impacts. Claims that only limbs, scrap and waste wood was being processed into pellets were disputed; logs suitable for conversion into lumber were clearly being used at Enviva's plant in Northampton, North Carolina. After the plant opened in 2013, logging nearby increased by 50%.

A whistleblower in 2023 exposed that branches/limbs were being left in the woods rather than processed into pellets, because the pellet density was increased by using the trunks of trees. Instead of being a "green" energy company, Enviva was contributing to deforestation of forests in the Southeastern United States.

The company's planned mix of 80% hardwood scrap and 20% pine was reversed. Because Enviva was competing with lumber mills to purchase logs, costs exceeded revenues. The dividend was cancelled, and in one day the stock price dropped from $21 to less than $8 per share. At its peak in 2022, the stock was worth $80/share. The drop continued and in November 2023, the price was down to $1.50/share.

Enviva had 10 plants in the Southeastern United States in 2023 and another under construction, with strong demand by customers and a reliable supply of wood - but it declared bankruptcy in March 2024. Even in a favorable environment for selling pellets, the company had seriously miscalculated the costs required to meet its commitments to deliver the final product to customers. Enviva sought court action to break contracts, and proposed that shareholders lose 95% of their equity investments.

the Enviva plant in Southampton County can produce 760,000 tons of wood pellets per year

Source: Enviva, Enviva Southampton

Virginia's plants burn wood chips to generate electricity, but an extra processing step is required to export biomass across the Atlantic Ocean. Since raw wood is typically 50% moisture, logging residue is converted into wood chips, dried, ground to powder, then compressed into pellets to create a higher-density product. By the time utilities in Europe buy the pellets, the cost of the original logging residue has increased 600%.12

To support its export plans, Enviva acquired the Giant Cement Co. terminal in Chesapeake and constructed storage facilities for pellets coming from Virginia and North Carolina facilities. Enviva planned to load 2-3 ships with wood pellets, every 10 days. Great Britain is a major destination for Virginia's wood chips, especially after a utility in Selby, England converted a coal-fired power plant there to burn pellets.13

Competing companies planning to manufacture and export wood pellets announced plans for wood pellet production in Greensville County and near the city of Franklin, taking advantage of low wood prices after International Paper closed its mill in Franklin.

One Enviva competitor, ecoFUELS, leased 15 acres at the Portsmouth Marine Terminal in 2012. ecoFUELS drew attention as the first long-term tenant at Portsmouth Marine Terminal since container operations were shifted to APM Terminal in 2011, and because a major investor was the Democratic candidate for governor, Terry McAuliffe, in 2013. The extensive forests in the region, together with easy access to export terminals in Hampton Roads, spurred proposals for supplying biomass to European customers:14

DRAX planned to build several BioEnergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) power plants in the southeastern states by 2023. Each plant, burning wood chips and sequestering carbon emissions underground, would cost $1 billion.

The company anticipated a demand from data centers providing Artificial Intelligence (AI). Technology companies such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google had made pledges to reduce carbon emissions, and they needed reliable power 24 hours/day. DRAX anticipated selling electricity generated from wood chips, competing with wind/solar with battery storage and nuclear power plants. The company's chief executive said at the end of 2024:15

a major wood pellet production plant is just south of the Virginia border in Northampton, North Carolina

Source: Southern Environmemtal Law Center (SELC), A case of wood pellet pollution versus community

One other potential source of fuel for biomass-produced energy, beyond forest products, is the production of crops directly for energy. The economics indicate that growing annual crops for "direct thermal conversion processes" (i.e., burn biomass to generate heat/electricity, without initial conversion into biofuels such as ethanol) will require major subsidies. As one researcher noted in a 2010 biomass meeting, energy companies were willing to pay only 25% of the cost of producing the crop. Without a subsidy equal to 75% of the cost of production, there was little potential for farmers to shift away from traditional food crops in order to grow material for biomass operations.16

A more-likely scenario is that crop residue could be utilized for energy. The primary crop would be sold for food, but leftover components might be converted into energy. Use of crop residues such as wheat straw and corn "stover" for energy (cob, husk, stalk, and leaf, everything except the high-value kernels) would match the use of logging residue from timber harvest operations to fuel biomass plants.

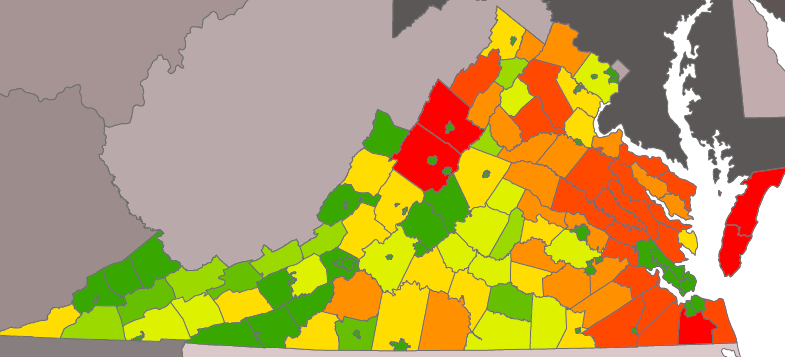

geographic distribution of corn stover in Virginia reflects the patterns of agriculture, with Accomack and Augusta counties providing the highest levels of crop residue

Source: Preliminary Residual Biomass Inventory for the Commonwealth of Virginia (p.22)

The Department of Energy estimated that 35% of the residue after harvest of grain crops could be utilized, with the other 65% required for soil conservation, animal grazing, or other farm-related purposes. The cost to collect and transport crop residues limits the economic potential; corn stover and wheat straw have low amounts of energy compared to the potential heat value for burning as fuel to generate electricity.17

Research for crop residue focuses on converting it into energy-dense biofuels, using on-farm digesters to minimize transportation costs. That approach parallels the decisions made by farmers on the western frontier of Virginia in the 1700's, in places without good road access to market cities. Producers of corn, wheat, rye, and barley in isolated areas could not afford to ship grain long distances by wagon. The logical alternative was to digest the grain, converting it into a product with lower volume and higher density - whiskey.

Southeastern Virginia, the Northern Neck, and the Eastern Shore have the greatest potential to provide crop residues for biomass energy

Source: US Department of Energy - National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Crop residues

One early adopter of alternative energy sources was Riverhill Farms in Rockingham County. To reduce the costs of heating turkey houses with propane, it started burning corn, wood chips and turkey litter. In 2010, it was selected as a demonstration farm for the Chesapeake Bay Farm Manure-to-Energy Initiative, a collaborative effort to find ways to reduce phosphorous pollution from excess poultry litter.

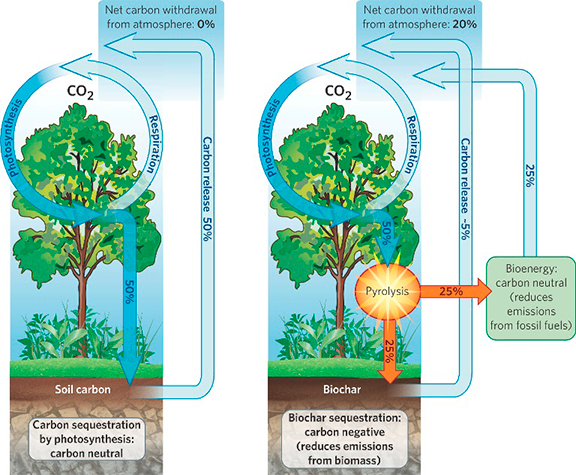

Heating the turkey litter in a closed container without oxygen created biochar. It could be used as a soil amendment, or burned to generate energy. The dried manure was also cheaper to transport to a disposal site where there was not already an excess of phosphorous in the soil. The Chesapeake Bay Program highlighted that benefit:18

In Floyd County, SWVA Biochar planned to manufacture biochar in 30 oxygen-free ovens from waste wood products and mix it with chicken litter to create a soil amendment. One possibility was to put the biochar in the bedding used by the chickens, rather than mixing it later with chicken litter.

The plan was for the final product, with the right balance of phosphorous and carbon, to convert chicken waste from an expensive burden on the Eastern Shore into a valuable fertilizer. As described by a manager at SWVA Biochar:19

In 2022, Restoration Bioproducts announced plans to build a new $5.8 million biochar plant in Sussex County. The company would take the waste generated from production of the EasyPellet brand of wood pellets by Wood Fuel Developers, heat the waste material via pyrolysis (in the absence of oxygen) to create biochar and syngas, then burn the syngas to generate electricity. The biochar would be sold as an agricultural soil amendment, or for various other uses that took advantage of its capacity to absorb odors.

The project would also sell carbon credits. Roasting plant matter in an oxygen-deprived environment, converting cellulose and other carbon-rich molecules in plant material to biochar, stops the normal biological decay process. That extends the time of carbon sequestration from years into centuries. The technology to create biochar is readily available, unlike high-tech and unproven proposals for Direct Air Capture or other forms of carbon sequestration.

As described by the board chair of the International Biochar Initiative:20

biochar delays return of carbon into the atmosphere

Source: International Biochar Initiative, Sustainability and Climate Change

In 2020, the General Assembly passed the Virginia Clean Economy Act and required Dominion Energy to close its three biomass facilities by 2028. In 2023, the legislature dropped that requirement, while also declaring electricity generated from biomass facilities to be "renewable energy" - so long as no coal was burned with it in co-fired generation. That provision excluded electricity generated at the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County from being defined as "renewable."

Environmental groups did get the General Assembly to order a life-cycle carbon analysis of the carbon in biomass, to better evaluate the positive and negative impacts of burning it to generate electricity. However, Dominion Energy, NOVEC, and the Virginia Loggers Association were unwilling to share "market sensitive" data on the volume of wood delivered by contract loggers to power plants. The volume of wood waste used by the WestRock paper mill in Covington and the International Paper mill in Franklin were also not clear to the study team.

A concern was that burning forest slash was accelerating the conversion of wood waste into carbon dioxide that was emitted into the atmosphere. If left in the woods after a timber harvest, tree branches and wood not suitable for lumber would decay far more slowly. In contrast, waste delivered from sawmills would decay quickly.

The climate benefits from stopping the burning of biomass would be far less, if most of the biomass being burned at power plants was largely from sawmills. If the study group could not determine the percentage from sawmills vs. forests, then the value of the study would be greatly reduced.21

wood waste left in the forest decomposes and releases carbon dioxide far slower than sawmill waste

Source: John Lloyd, slash

The 2023 legislature rejected the governor's effort to authorized NOVEC to sell Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) for the electricity generated by burning wood waste at its Halifax plant to Virginia buyers.

Dominion had been authorized to sell RECs from its wood-burning facilities because the utility was required to produce a certain amount of electricity to meet a Renewable Portfolio Standard. NOVEC had been blocked from selling RECs in-state, because it was not required to meet a Renewable Portfolio Standard.

The governor's rejected amendment in 2023 would have required NOVEC to generate 148 megawatts of renewable energy in addition to the output from the Halifax plant, before selling the REC's. That would have created the equivalent of a Renewable Portfolio Standard for the co-op. The renewable generation could come from any source within the PJM regional electrical grid, had the amendment been approved.

NOVEC's Chief Executive Officer explained the relationship between the mandatory Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) and selling RECs:22

One possibility for using biomass was to convert it via pyrolysis into a bio-oil which could be injected underground. That sequestered carbon, and was justified because large corporations were seeking ways to offset their greenhouse gas emissions that were triggering climate change. Heating "stover," the leftover stalks, leaves, and husks of corn and other crops, in kilns without oxygen produced a fluid that could be pumped deep underground. Purifying and refining the pyrolysis bio-oil for other uses was not cost-effective, but if sequestered it would qualify for carbon offsets.

The pyrolysis process also created bio-gas which could be burned to generate heat, and biochar which could be used to amend soil and increase its productivity.23

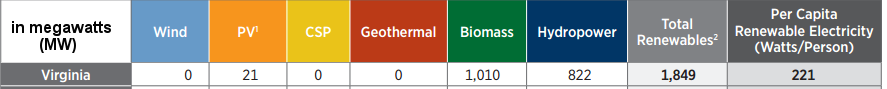

in 2015, Virginia had more installed capacity for generating electricity from biomass than from hydropower sources

Source: US Energy Information Administration, 2015 Renewable Energy Data Book (Cumulative Renewable Electricity Installed Capacity - South)

in 2021, burning wood was the third largest source of producing electricity and industrial heat in Virginia

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Virginia - State Profile and Energy Estimates

pellets are produced by chipping, drying, and compressing wood to create a fuel with higher energy density than raw wood waste

Source: Tennessee Valley Authority, Biomass Direct Generation

forested areas near the paper mill in Franklin offer the greatest potential for residue/slash suitable for wood pellets and biomass energy plants

Source: US Department of Energy - National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Virginia Biomass Resource