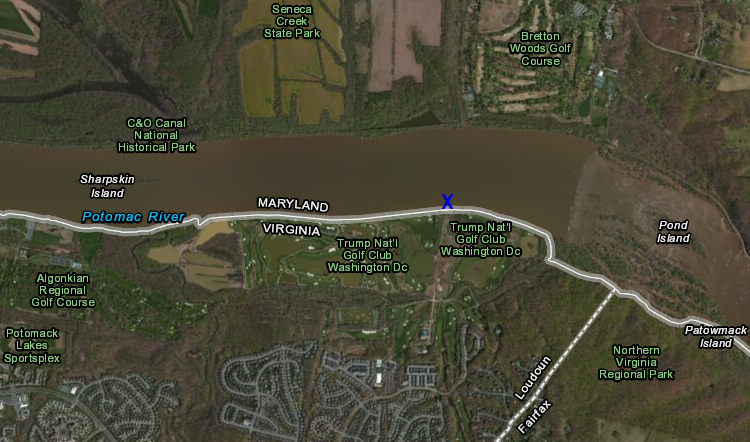

the intake for Fairfax Water's Corbalis drinking water treatment plant is in Maryland, and the pipe crossed the Trump National Golf Club

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the intake for Fairfax Water's Corbalis drinking water treatment plant is in Maryland, and the pipe crossed the Trump National Golf Club

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After centuries of disputes, negotiations, arbitration, and court cases, it is clear that Maryland owns the Potomac River to the low-water mark on the Virginia side... but that boundary still creates confusion.

In 1986, a man was convicted in Loudoun County of murdering his ex-wife. In 1988, that conviction was overturned by the Virginia Court of Appeals because the body had been found floating in the Potomac River at least six feet away from the shoreline. Under homicide law, prosecution occurs where the body is found unless the actual location of the crime is unknown, so the body was in Maryland and officials from that state had to pursue the murder case.1

Further downstream, Virginia and Maryland have continued to debate Maryland's control over the bottom of the Potomac River. The 1958 Maryland-Virginia Compact replaced the Compact of 1785 in hopes of resolving disputed claims to oyster beds and fishery resources, but lawsuits continue to cite colonial-era documents as well as the 1958 agreement.

In 1997, Maryland claimed that the Fairfax County Water Authority needed a Maryland state permit in order to extend a water pipe to the middle of the Potomac River. Fairfax wanted to minimize the sediment in the water that it will treat at its Corbalis Water Treatment plant, near the Loudoun County line, by extracting raw water from the middle of the river.

The old Fairfax County intake pipe on the southern shoreline was receiving water with too much sediment, partly due to muddy runoff from housing developments in Loudoun County. Fairfax wanted to suck cleaner water from the middle of the river. The water in the middle of the Potomac River is cleaner, in large part because C&O Canal National Historical Park on the Maryland side provides a buffer of natural vegetation and there is less mud flowing into the Potomac on the north bank.

location of intake for Fairfax Water's Corbalis drinking water treatment plant

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

That 1997 proposal created yet one more Virginia v. Maryland lawsuit in front of the US Supreme Court.

Maryland opposed the plans of the Fairfax County Water Authority (now Fairfax Water). It tried to force the Virginia county to get a Maryland state permit before constructing the intake pipe on the bed of the Maryland river. Part of the "back story" is that Maryland wanted Virginia to reduce the impacts of shoreline development that pollute the Potomac River. Simply avoiding those impacts by extending the intake pipe addressed the symptom without dealing with the cause.

In 2003, the US Supreme Court ruled that Fairfax County has the right to place the intake pipe on Maryland's river bed without having to obtain a permit from Maryland. Though Maryland owns the whole river due to the wording in the 1634 charter, various bi-state negotiations and court decisions (including the 1877 Black-Jenkins Award) have made it possible for Virginia to use the Potomac River.

In particular, the Maryland-Virginia Compact of 1785 said:2

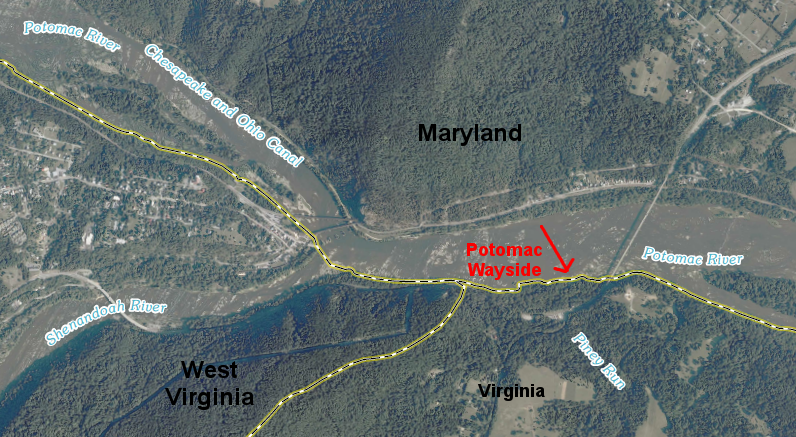

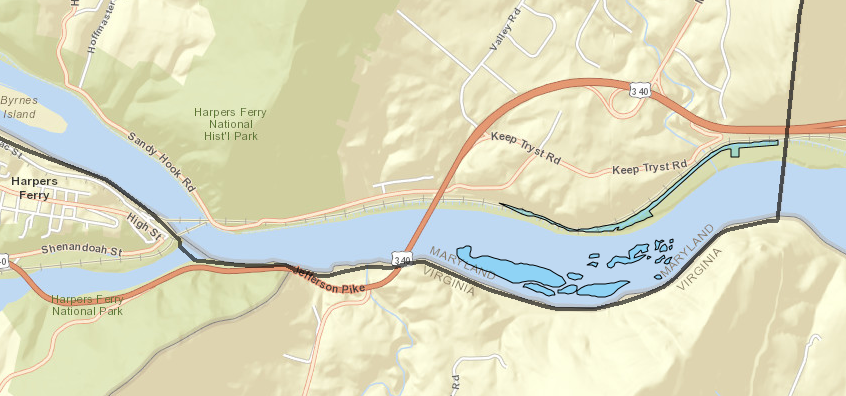

In 2011, landowners in Maryland claimed control over the riverbank downstream of Harpers Ferry, on the Virginia side of the river at Potomac Wayside. Maryland sold rights to the bottom of the river until 1862, and the parcel in dispute has been private property since 1833.

location of boundary dispute downstream of Harpers Ferry

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Harpers Ferry 7.5 x 7.5 topographic map (2011)

Potomac Shores, Inc. asserted that their 1833 deed described property boundaries that extended to the median high-water mark (the average of the water level throughout the entire year) on the southern bank of the Potomac River. Based on that claim, canoeists and rafters who floated downstream past Harpers Ferry 175 years later were trespassing on private property in Maryland when getting back on dry land at Potomac Wayside. The company also claimed the rocks above water in the middle of the Potomac River were private property as well.

tax assessor maps of river bottom owned by Potomac Shores

Source: Washington County, Maryland, Zoning Map Viewer (Map 0088, Parcel 0047)

The commercial outfitters had obtained permits from the National Park Service to use Potomac Wayside, and paid fees to the Federal agency. Potomac Shores claimed its deed documented a strip of land between the low-water mark and the median high-water mark was privately owned, and sought to force commercial outfitters to pay fees to Potomac Shores as well.3

In a tactical legal decision, Potomac Shores filed suit against the commercial outfitters in a Maryland court. The company did not pursue a suit against the National Park Service to quiet title for the land; the Federal agency had far more resources for defending their claim. The outfitters did not compromise in order to minimize their legal expenses (estimated at $10,000).

Judge Long of the Washington County Circuit Court of Maryland ruled in 2013 that the 1877 Black-Jenkins arbitration decision had settled the issue:4

The Court of Special Appeals of Maryland affirmed that decision in 2014. When sediments on the southern shoreline of the Potomac River shift, the low water line shifts. The Virginia-Maryland border follows that shifting boundary, and all land above the high-water mark on the Virginia side of the river will be in Virginia.5

Virginia has bargained with the District of Columbia on how to fund replacement of the Long Bridge, almost all of which crosses Potomac River water within the District. The two-track railroad bridge was the bottleneck that blocked expansion of Virginia Railway Express (VRE) commuter rail service from Northern Virginia into the District of Columbia. Virginia proposed to revise the limits on funding from the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA), order to allow that regional agency to contribute to a project outside the boundaries of Northern Virginia.

In three cases, Maryland and Virginia have succeeded in negotiating boundary-crossing deals rather than disputing ownership rights. Both states wanted to replace the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, Gov. Harry W. Nice Memorial/Sen. Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge, and American Legion Bridge crossing the Potomac River. Virginia chose to partner with Maryland rather than seek to base its share of the costs on just the percentage of the bridges in Virginia.6

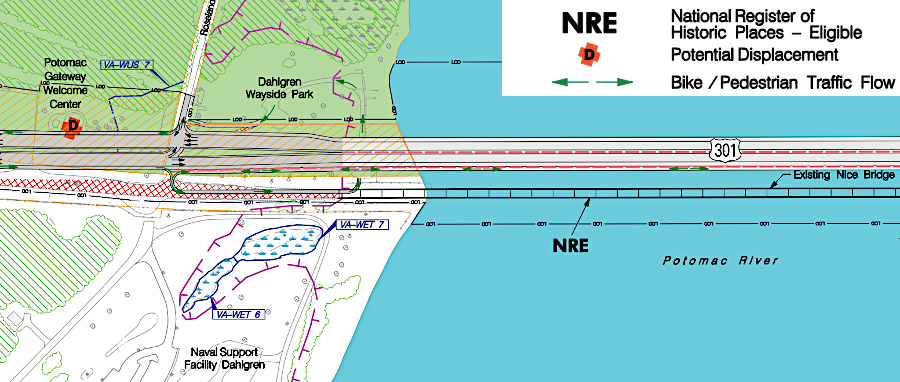

Maryland had full authority to design and build a replacement for the Nice Bridge, and then demolish the old structure in 2022. (The name of Maryland State Senator Thomas "Mac" Middleton was added to the bridge honoring Governor Nice, after he sponsored legislation for the replacement bridge.)

State officials in Virginia did not object when Maryland eliminated the planned bike/pedestrian lane on the new span. Three hiking/biking groups - the Potomac Heritage Trail Association, the Dahlgren Railroad Heritage Association and the Oxon Hill Bicycle and Trail Club - had to file a private lawsuit to retain the old bridge in order to preserve a safe connection for non-motorized traffic across the Potomac River.

A Federal judge ruled against the groups, allowing the Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA) to remove the old bridge and dynamite the pilings which supported it. Arrangements for bikers to use the travel lanes were promised in 2023, but there were no provisions for pedestrians to cross the new bridge.

the old Nice Bridge lacked safe access for bike/pedestrian traffic (and the new bridge did not provide the planned dedicated lane)

Source: Wikipedia, View south along U.S. Route 301 (Governor Harry W. Nice Memorial Bridge) crossing the Potomac River from Charles County, Maryland to King George County, Virginia

In what may have been unplanned irony, State Senator Thomas "Mac" Middleton commented regarding the original plan to include a dedicated bike/pedestrian lane on the new bridge:7

Maryland proposed one design for the new bridge with a dedicated bike/pedestrian lane, then revised the design to reduce costs

Source: Governor Harry W. Nice Memorial/Senator Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge Environmental Impact Statement, Finding of No Significant Impact/Final Section 4(f) Evaluation (Appendix A. Modified Alternate 7 - Selected Alternate)

the Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA) proposed allowing bikers to cross the new bridge by sharing a travel lane with cars/trucks

Source: Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA), Nice/Middleton Bridge Project