roadside taverns served whiskey, beer, rum punch, and other forms of alcohol, and provided community gathering places

Source: Library of Congress, Barroom dancing (by John Lewis Krimmel, c.1820)

roadside taverns served whiskey, beer, rum punch, and other forms of alcohol, and provided community gathering places

Source: Library of Congress, Barroom dancing (by John Lewis Krimmel, c.1820)

Native Americans in Virginia did not develop alcoholic beverages, so there was no beer, wine, or hard liquor crafted in Virginia until the arrival of the Europeans. Mind-altering states were achieved by other means, including brewing tea from the caffeine-rich (Ilex vomitoria).

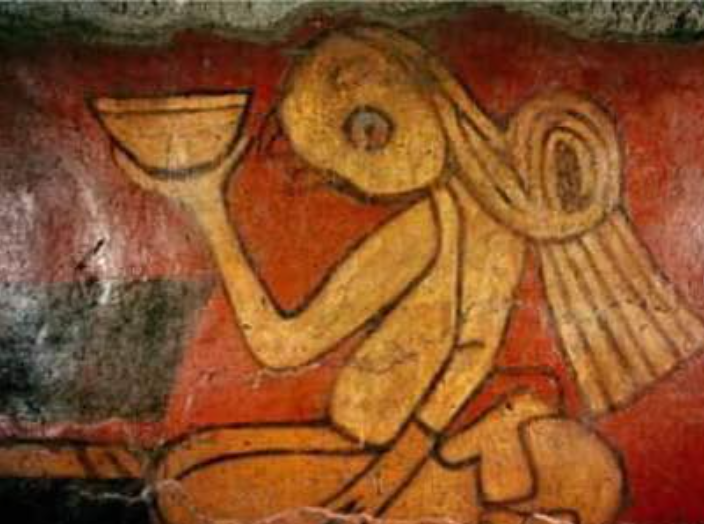

In Central and South America, alcohol was readily available even before Native Americans in Virginia switched from the atl-atl to the bow and arrow. In Central Mexico, milky white sap from the agave plant was fermented to create a low-alcohol beer known as pulque.

The agave juice fermented within hours, and pulque was drunk regularly soon after it was made. The 1,800-year old Mural of the Drinkers ("Los Bebedores") depicts 164 people drinking pulque in a ritual ceremony, which was a time for making a more potent drink.

In the Andes as long ag as 5,000BCE, chicha was made by chewing corn or other starchy products such as potatoes. Chewing added enzymes from human saliva, and they decomposed starches into sugars comparable to the modern process by which grains are sprouted to create malt. Yeast then fermented the sugars into alcohol.

The lack of beer or wine in Virginia's Native American communities is unusual. Dr. Patrick McGovern, the archeologist who first developed the science of studying ancient vessels to identify the residue of alcoholic beverages ("drinkology"), noted how fermenting food to create bread and alcohol was a fundamental trait in different societies:1

in central Mexico, agave was fermented to produce alcoholic pulque 1,800 years ago

Source: Government of Mexico - National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), "Los Bebedores" de Cholula

The Spanish, English, and other sailors who came to the Chesapeake Bay brought rum. The first successful distilling effort by an English colonist, George Thorpe, produced a batch of corn whiskey in 1620. Alcohol became a popular trade item between the European colonists and the original residents of Virginia.

Beer and liquor are normally manufactured from corn, rye, and other grains. Wine or cider is produced from grapes, apples and other fruits. To create alcohol, typically carbohydrates in starch are converted into sugar by boiling. After cooling, yeast transforms the sugar molecules into alcohol and carbon dioxide bubbles away as a waste product.

Europeans were unfamiliar with making liquor from corn until after the Spanish discovered the New World in 1492. English colonists settling at Jamestown quickly discovered that they could use corn instead of rye, wheat or barley to make alcohol:2

The English colonists also tried to make wine from the native grapes. Because there was so little sugar in those native grapes, the fermentation process created very little alcohol. In addition, the grapes had a high acid content, and grapes from the "fox grape" (Vitis labrusca) contained a bad-tasting chemical also found in the musk of foxes.3

The colonists made beer, distilled brandy from local fruit, and imported rum made from sugar cane grown on the Caribbean islands. There were no Manhattans or Moscow Mule cocktails then, but mixing different components was common. A popular drink was "flip," made with a combination of beer, rum, dried pumpkin, plus eggs or cream. The ingredients were stirred together in a container, then a hot metal rod ("flip-dog") would be thrust into the center. The heat cooked the eggs and caramelized the sugar, creating a sweet and frothy drink.

As described by Colonial Williamsburg:4

Alcohol was a common component of everyday life. Cider was easy to create from locally-grown fruit. "Small beer" with a naturally low alcoholic content was brewed from wheat bran, hops, water and molasses imported from the Caribbean. By 1621, hops were grown near Jamestown to add spice flavor to the local beer. Persimmons and various herbs were used as well to create distinct flavors.

Beer was not bottled, and the preservative value of hops was marginal because beer was consumed so quickly. After the grain/molasses/herbs were mixed together and brought to a boil, whatever yeasts were present within the air near the pot stimulated fermentation. Ale was the most common form of beer, because it was created by yeasts which fermented best around 60°°F. Lagers might be created when temperatures averaged around 40°F

In the 1600's beer was brewed every week in individual households by the women in the kitchen as a standard food item. In a local community, women might arrange for different husholds to brew small beer and share with others in a rotation of workload.

Around the 1700's, brewing shifted to being a commercial business. Gender roles changed as beer became a product sold to strangers; men took over the role as brewers. Small planter households continued to make cider and small beer for the second half of the year, when grains and fruit were available. Large planters had the resources to distill liquor and store it in barrels. Until the 1760's, when enough taverns were finally available to offer an alternative, small households typically purchased distilled alcohol from the large planters during the first half of the year.

Men drank 8-10 beers daily to stay hydrated while working outdoors, and children and wives drank beer routinely as well. Beer was thought to be safer than drinking the alternatives:4

by the 1700's, Virginia men began brewing and selling beer as a commercial business operation

Source: National Park Service, Brewing in the Seventeenth Century

Cider from fruit and beer were brewed at home, primarily by women in household kitchens through the 1600's. The low-alcohol product was difficult to store, so alcohol was traded through a barter system where different chores were exchanged. Later, alcohol production shifted to larger operations requiring more equipment. Brewing and distilling were "re-gendered" out of the kitchens dominated by women, and became a responsibility of men.5

Much of the alcohol created by Virginia's colonists in the 1700's was brandy produced from orchard fruits (especially apples), rather than distilled from grains such as corn or rye. Only the wealthy owners of large plantations had the capital to set up a distillery. After fruit trees were planted and began producing, the fruit was harvested and fermented into cider with the alcohol equivalent to what is in a beer today. Cider could be reprocessed through distillation into a higher-alcohol brandy, which could be stored and transported easily compared to beer/cider.

The wealthy elite also could make arrangements to import other forms of liquor from England, France, or the Netherlands, or rum from the Caribbean. Large planters such as George Washington typically sold their crop through "factors," representatives in England who charged high prices to sell hogsheads of tobacco delivered to England and to buy manufactured goods/luxury items requested by the large planters. Small farmers settled for beer/cider, or purchased hard liquor from those large planters.

The traditional pattern of alcohol production and sale changed after passage of a law in 1730 to create tobacco inspection warehouses. New towns developed near tobacco inspection warehouses in Tidewater, and Scottish merchants opened stores in those town. The merchants came to Virginia to buy tobacco directly, provide credit immediately to the tobacco growers, and then recycle that credit back into the merchants' pockets by selling items - including brandy and hard liquor in wooden casks - to the tobacco growers.

Alexander Henderson of Dumfries is known as the "Father of Chain Stores" because he opened multiple stores in separate locations to dominate business with small farmers from Stafford County to Alexandria. Thanks to his stores, small farmers no longer needed to ask large planters to order items from England as a favor and to wait up to 18 months for delivery.

The new towns that emerged after the 1730 tobacco inspection act also led to the emergence of taverns to shelter and feed travelers, and created a market for commercial sale of liquor at those taverns.

George Washington built his distillery in 1797, speculating that he could convert rye and corn selling at a low price into a more-profitable product. When he died in 1799, Washington's distillery was the largest in the United States.

Mount Vernon has rebuilt George Washington's distillery, next to his mill on Dogue Creek

The product from George Thorpe's 1620 distilling and George Washington's industrial scale operation was whiskey, but not bourbon. Thorpe's whiskey was made from corn, but not aged in charred barrels made from white oak. Washington's whiskey was made from rye, not corn. Neither meet the definition of "bourbon." Both would qualify as "whiskey," the American way of spelling what distillers in Scotland (and the distillers of Maker's Mark bourbon in Kentucky) spell as "whisky."6

Smooth-drinking Virginia bourbon, aged in charred oak barrels for seven or so years, was not developed until after the Revolutionary War. Prior to 1800, rum imported from the Caribbean was the primary liquor in Virginia. Virginia ships would carry pork and wheat to the islands and return with slaves, rum, and sugar. Rum was usually mixed with sweet juices and served as a punch. Various types of punch could be formed by different combinations of alcohol, juices, and sugar to create a special treat in colonial times:6

Before he opened his distillery, George Washington was well-versed in the economics of converting grain into rye whiskey. One of the major challenges that he faced in his second term as president was the Whiskey Rebellion. It helped two Virginia leaders establish the authority of the new Federal government.

Washington's Secretary of the Treasury (Alexander Hamilton) convinced the US Congress to impose an excise tax on whiskey in order to fund the Federal government. The Federal government needed revenue to pay for the Revolutionary War debts absorbed by the Federal government from the states, in the compromise that had resulted in the capital being located on the Potomac River.

Farmers in western Pennsylvania felt the new Federal tax on whiskey was unfair. It was not economical to ship grain to Philadelphia or New York because the roads over the mountains were so poor. Distilling grain into whiskey reduced the bulk. One bushel of grain became one gallon of whiskey; one acre of grain could be converted into forty gallons.

Distilling grain into whiskey produced a high-value product that would not spoil and was easy to transport. In the first decades of the United States, before the construction of canals and railroads, most of the western whiskey may have been sold in local markets west of the mountains rather than shipped to Eastern seaports or New Orleans. When the region had few good roads connecting farms to markets, it was still easier to haul a few barrels to local taverns than to haul wagonloads of grain to local mills.

Pennsylvania farmers refused to pay Federal taxes on whiskey and physically blocked tax collectors from doing their job, while officials in the new state of Kentucky took a simpler approach: they just refused to collect the excise tax.7

President George Washington assembled an army of over 10,000 troops - the largest force of revenuers ever created - to suppress what was portrayed as an armed rebellion against the new Federal government. Virginia Governor Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee led the troops from Bedford, Pennsylvania into the western part of Pennsylvania.

Washington had understood the importance of symbolism and drama since his early youth in colonial Tidewater society. The refusal of those Pennsylvania farmers to pay Federal taxes on whiskey gave the first president of the United States a chance to demonstrate that the national government was empowered to enforce within the states laws passed by the US Congress created by the new Constitution ratified in 1788.

Washington, Adams, and Hamilton took advantage of the crisis. They used the Whiskey Rebellion to draw a clear contrast between the powerful Federal government created by the Constitution ratified in 1788 vs. the weak national government that existed under the old Articles of Confederation. The military force that Washington assembled in 1794 included far more soldiers than was necessary to defeat a few poorly-armed farmers; he wanted to ensure that the supremacy of the Federal government was clearly recognized.

The 1794 Whiskey Rebellion was one of the first sectional threats that could have broken the union of the United States, which finally occurred with secession of southern states followed by a civil war in 1861-1865. Once "Light Horse Harry" Lee marched into western Pennsylvania in 1794, the rebellion dissolved and pardons were quickly issued for most participants.8

Transporting grain across the Blue Ridge of Virginia was also not economical. Distilling became a tradition in the Blue Ridge of Virginia, as small farmers converted high-volume, low-value wagonloads of grain into easy-to-transport barrels of whiskey. When Prohibition blocked sale of alcohol through official channels, liquor production continued. It was called "moonshining" because, in theory, the stills were heated at night when smoke would not be so visible.

Virginia implemented Prohibition before the national ban was established through an amendment to the US Constitution. In 1903, the General Assembly passed the Mann Act, which essentially limited sales of alcohol to just urban areas. The entire state voted in favor of Prohibition in 1914, and it went into effect on October 31, 1916.

In 1933, Virginia was the 29th state to ratify the 21st Amendment to the US Constitution ending Prohibition. Over 60% of Virginians voted in favor of ending prohibition and creating a state-controlled monopoly to manage liquor distribution and sale. Prohibition ended in Virginia in 1934.9

hop vines growing on porch, Blacksnake Meadery