newly-planted grapes at LaGrange Winery in Prince William County (opened 2006)

newly-planted grapes at LaGrange Winery in Prince William County (opened 2006)

The oldest known fossil of a grape seed dates back to the time that dinosaurs went extinct, 66 million years ago. Based on the fossil evidence, grapes now in the genus Vitis evolved initially in the western Hemisphere. The oldest fossils appear to be direct ancestors of the Vitoideae family, which includes commercial grape varieties now being cultivated.

As forests recovered from the asteroid impact which formed the Chicxulub crater, there were no large herbivores to graze high branches. Without dinosaurs the new forests created a closed canopy, blocking sunlight from reaching the ground. Vines such as grapes then evolved to climb trees in their fight for light that allows photosynthesis. Everyone drinking a glass of wine today owes a small debt to the asteroid that created the Chicxulub impact crater.

Wine from fruit and honey was probably the first alcohol produced by humans. Early humans probably carried ripe/overripe fruit back to their shelter, where natural fermentation by yeast created an alcoholic juice at the bottom of the containers and created what one author calls "a kind of Stone Age Beaujolais Noveau." Purposeful, regular production of alcoholic beverages may have started in China, but cultivation of grape vines (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera) began in what today is the Near East - Turkey, Iran, Georgia, and other countries near the Caucasus Mountains.1

Wine production may have occurred before beer production. Beer, produced through fermentation of carbohydrates in grains such as barley/wheat/rice/corn, tubers such as cassava, or the sap of the agave plant requires an extra step. The complex molecules of starch carbohydrates must be transformed into simpler sugars through the extra step of sprouting/conversion into malt. The easiest way to convert the starch into simpler sugar molecules is through chewing (mastication), where the phytase enzyme present in human saliva does the conversion.

Pulque was produced in central Mexico by capturing sap from the agave plant, then letting it ferment naturally. The milky sap ended up as a low-alcohol beer. Pulque spoil quickly, so pulque production may have been an almost-daily task.

The original domestication in southwestern Mexico of the grain teosinte, precursor of modern corn, may have been driven by use of the stalk for making corn wine. If that was the case, only later did growing teosinte kernels for food become the primary objective, ultimately leading Native Americans to genetically modify the species by selective breeding to create large ears of corn. Pottery may have been used initially in South America 7,000 years ago to store chicha, a beer made from fermenting corn after chewing the grains.2

When Europeans arrived to settle in Virginia in 1607, the Native Americans in Virginia produced no alcoholic beverages. Alcohol had been crafted by other New World residents for thousands of years, using agave, cacao pods, cacti, cassava, maize, palm, sweet potatoes, and a variety of fruits (including the berries from the Peruvian pepper tree). Native Americans in Virginia learned from others, including how to grow corn and make pottery, but alcohol production was never adopted. Outside of what is now the southwestern United States, tobacco or mushrooms may have provided sufficient mind-altering capabilities and alcohol was not desired by the original residents of North America.3

The early colonists quickly discovered that the raw material for wine was abundant in Virginia. The Vikings who explored North America around 1000 CE (Common Era) named the new continent Vinland ("land of wine") because grapevines were common. Captain Bartholomew Gosnold named an island off the New England coast "Martha's Vineyard" in 1602. English colonists discovered the Algonquian-speaking Native Americans along the East Coast were growing grapes. The Croatoans on Roanoke Island may have been tending the "Mother Vine" in 1584.

making wine in colonial Virginia, using grapes from a vineyard rather than collected from wild vines

Source: National Park Service, Wine Making: A 17th-Century Enterprise (from Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings)

The Europeans who sailed across the Atlantic Ocean roughly 600 years after the Vikings were not teetotaler. The sailors and early colonists were accustomed to using alcohol as a source of calories and pleasure. The settlers at the Plymouth Company's Popham colony, near the mouth of the Kennebec River in modern-day Maine (at 44°N, comparable to Bordeaux, France) may have been the first Virginians to make wine from native grapes in the fall of 1607. The northern colonists may have made their wine a year earlier than the London Company colonists, 650 miles further south in Jamestown - which was located in the same latitude (37°N) as Gibraltar and Sicily.4

John Smith recorded grape vines in Virginia were in "great abundance in many parts... covered with fruit" and "we made neere twentie gallons of wine." In 1610, Lord de la Warre wrote back to the London Company that he had found the colony in the process of being abandoned due to lack of food, but he quickly recognized the potential of making wine:5

modern vineyard on Carter's Mountain next to Monticello (Albemarle County)

Governor Thomas Dale was a professional military man who, as governor, sought to impose strict discipline on the colony through the Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall - and also planted a three-acre vineyard in 1611, using local Virginia grapes. The London Company tried to make a profit from exporting wine from Virginia, competing with the French, before the colony discovered the tobacco business could displace the Spanish control of that market.6

in 1647, a traveler in the colony noted the abundance of native grapes. He suggested the colonists be more energetic in making wine rather than shipping it across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe:7

Durand de Dauphine noted in 1686 that native grapes were common in the colony in the areas which received bright sun:8

However, the New World grapes were better suited for the wild foxes to eat than for the Europeans to convert into wine. Today some species of grapes native to Virginia are still called "fox grapes," but the wine we drink is coming from French grapes. The plants in the vineyards are often hybrids, with French plants grafted onto Virginia roots. The Virginia plants are resistant to disease, while the French grapes are far better for wine production. (However, if you have the taste buds of a fox, you might disagree...)

Haymarket in Prince William County had vineyards soon after the Civil War. Robert Portner is usually associated with his large brewery in Alexandria, but by the 1890's he too was growing grapes on his 2,000-acre Annaburg estate in Manassas. The Fairfax Herald reported a visit to Manassas in May 1895 to another winemaking operation:10

The Xander Wine Company in Washington, DC used Portner's grapes to made Virginia Port, Virginia Claret, and other wines. A wine made from those grapes won a medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition during the International Viticultural Congress, 76 years before a California wine was judged superior to French wines in a tasting made famous in the movie Judgment of Paris.11

Until the 1960's, it was generally accepted that American wines could not equal the quality of French wine. However, California used its university system to research new techniques for growing grapes and producing wine in the Mediterranean climate of that state. After years of state subsidy, innovative California winemakers developed new mechanisms for crafting fine wine. After they began to win medals *and* earn a profit, grape growing expanded north intro the Alexander Valley, to Mendocino, and to other cooler sections of California.

Virginia farmers in the Piedmont recognized that they could mimic California's success. Marginal pastureland converted to vineyards would generate far more income, assuming people would buy Virginia wines. One acre of grapevines can produce four tons of grapes, which can be converted into 120,000 bottles.12

In the 1970's and 1980's Americans began drinking more wine overall, and the Virginia gamble paid off. There were only six Virginia wineries in 1976, but by 2016 there were over 250.13

Mass market wineries in California and New York must maintain very low production costs, in order to compete on price rather than quality or esthetics. In 2015, wine grapes were grown on over 600,000 acres in California. Virginia grew wine grapes on slightly more than 3,000 acres.14

Virginia wineries are small producers crafting a niche product, rather than trying to sell high volumes of wine to the mass market. There is sufficient demand within the state to purchase all the wine bottled in Virginia; no Virginia wine will displace the long rows of Gallo or Taylor bottles on supermarket shelves.

Virginia has wineries small enough to be self-financed by one family. Some are operated more as boutiques, even personal hobbies, than as profit-making businesses. A winery in Central Virginia searched for an evocative historical Virginia name for its new wine in 2003. One appropriate name might have honored Theodore Roosevelt's nearby retreat, but customers were not expected to drink wine named after "Pine Knot."

Wine in Virginia is more than an agricultural product - it is a tourist product as well. The Virginia wineries make a profit by attracting visitors. To stimulate the tourist business, Virginia wineries engage in joint marketing efforts such as the "Passport To Virginia Wineries."

Tourists at a winery purchase meals, memorabilia, and wine. Direct purchases at a winery maximizes the winery's profit, by eliminating middlemen such as grocery stores. Tourists who enjoy the experience may return for another visit, and generate future wine sales.

In 2015, Virginia wineries attracted 2.3 million visits, in a state with a population of 8.3 million people. The visitors to wineries included repeat visits by Virginia residents, as well as out-of-state tourists.

Many wineries rely upon sales in their tasting rooms, minimizing the costs of transportation to retailers and capturing all the profit at the winery. At Afton Mountain Winery and nearby Veritas Vineyard & Winery, over 85% of their wines are sold onsite at the winery.

Winemakers worry that the inability to produce more product is limiting their exposure to new customers in restaurants, limiting the potential for future growth once more acres are producing wine grapes. In 2016 it cost roughly $20,000/acre to plant grapes in addition to the cost of the land, and a commercial harvest would not occur for another three-five years.15

There are now wineries on the Coastal Plain and Shenandoah Valley, as well as in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge. Locating a winery involves both agricultural and marketing skills. Tasting rooms of some wineries are located primarily for attracting tourists and potential new customers, and grapes are purchased from other locations rather than grown on site. In such cases, the unique mix of soil, topography and climate known as "terroir" is less significant than the winemakers talent for blending different juices, because the wine will be produced from grapes grown at other locations. Proximity to a major highway, making a tasting room easily accessible to tourists, can become the primary consideration in selecting a site.

The significance of terroir may also be altered by climate change. In France, the Institut National de l'Origine et de la Qualité has established an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) for 363 different wines produced using traditional processes from particular regions. Each wine has a distinctive character, and the designation helps customers recognize they are purchasing "authentic" products.

Of the 1,200 types of French cheese, 46 are allowed to print on their label Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP). Climate change is forcing a reconsideration of what cheeses are worthy of the "Protected Designation of Origin" label. That designation is a sign of quality to discriminating cheese buyers. It has enabled traditional cheesemakers to charge higher prices; it has helped preserve small farming operations as agriculture has industrialized.

Now, hotter and drier weather is reducing the acreage where goats can graze on specific grasses. Perpetuating past cultural practices may no longer be feasible as environmental patterns are changing.

One option is to alter long-standing requirements for earning the Appellation d’Origine Protégée designation, rather than force the cheesemakers to produce so little of the traditional product that they go out of business. A cheese association leader posed the basic question in 2023:16

Attimo Winery grew grapes in the middle of what was intended to be a rural subdivision in Montgomery County

In other cases, the winery is co-located with the grape-growing site. That was the case with the Attimo Winery in Montgomery County. The owner chose the location in part because it has the lowest average rainfall of any site in Virginia, just 18" of rain annually - comparable to Napa Valley in California.17

Grapes were planted on five lots originally planned to be part of a rural subdivision. The tasting room was built at the end of a cul de sac next to the grapes, but the vista includes other subdivision homes. With such esthetics, the potential for winery being a destination for weddings and other special events was limited.

Attimo Winery was welcomed by neighbors, who preferred a winery rather than five additional houses

Source: Montgomery County Geographic Information Systems

Northern Virginia offers especially-rich opportunities both to grow grapes and to attract visitors. Virginia's seventh American Viticultural Area (Middleburg AVA) was established on Oct. 15, 2012 by the US Treasury Department's Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. The name of that AVA in Loudoun and Fauquier Counties generated some controversy, with some comments proposing "Northern Virginia," "Greater Loudoun," "Northern Piedmont," and "Northern Virginia Piedmont" because "Middleburg" was too narrow a location. AVA's are the equivalent of brand names based on the unique physical character of an area, intended to:18

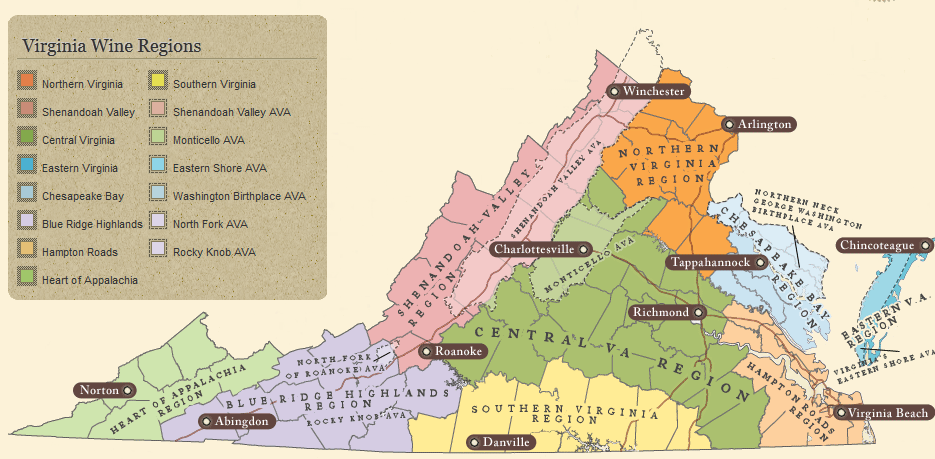

Virginia's six American Viticultural Areas and tourism-defined wine regions, before the seventh (Middleburg Virginia AVA) was approved in October 2012

Source: Virginia Wine

Viticultural areas are, at least in theory, places that share enough common characteristics for the wine to develop a common identity:19

The fast development of wineries in Virginia, in many cases by people who had recently moved to an area, makes the value of designating viticultural areas suspect. Designation is an attempt to transplant the European heritage of shared wine-making practices and shared physical characteristics, creating wines with shared properties. The innovative approaches used by different wineries also calls into question whether geographic proximity in Virginia will result in wines from one viticultural area sharing common characteristics, while being distinct from wines in another viticultural area.

More controversial than the name of the new viticultural area has been the debate regarding uses permitted at wineries. In 2007 the General Assembly, in its efforts to encourage wineries as an agricultural activity, limited the ability of local jurisdictions to limit activities at farm winery operations. According to one opinion:20

Despite the state law, in 2012 Fauquier County passed a local ordinance limiting the hours that wineries could be open to the public, how many events could be hosted in a month, and other activities that neighbors might consider to be more entertainment-related rather than farm-related.21

The Fauquier supervisors were reacting to complaints about loud parties, large weddings, and excessive traffic through rural neighborhoods. Fauquier lost, and wineries are evolving into rural event/entertainment centers. In Virginia, state law supersedes local ordinances, but the edges of authority between the state/county regarding land use controls at wineries is still being resolved by the courts.

Behold the rain which descends from heaven upon our vineyards, there it enters the roots of the vines, to be changed into wine, a constant proof that God loves us, and loves to see us happy.

(Benjamin Franklin, in a 1779 letter to the Abbé Morellet)22