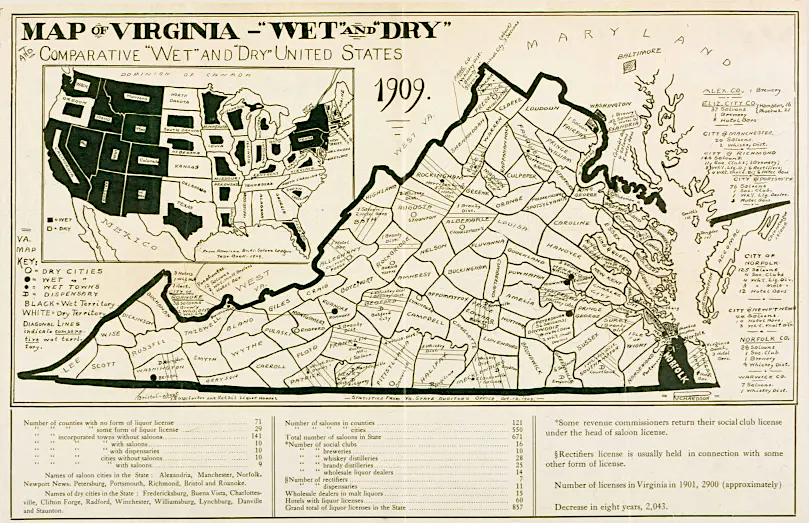

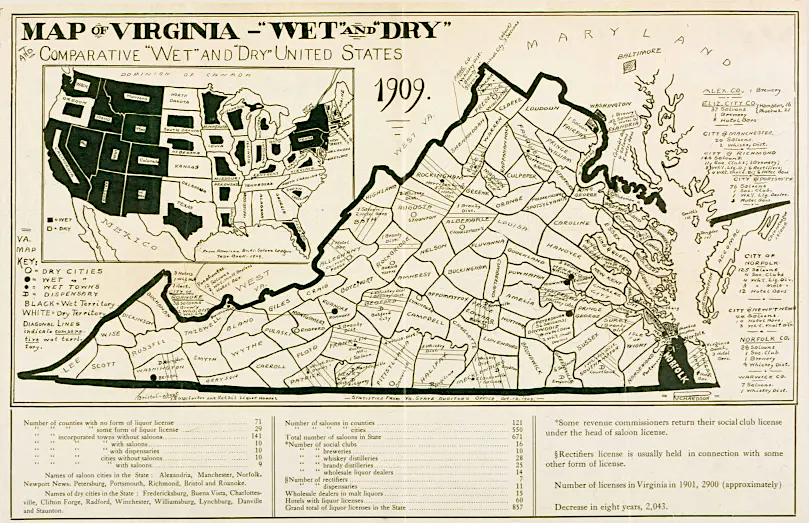

the 857 licenses to sell alcohol in 1909 was a 60% decrease from licenses in 1901

Source: Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia, Map Of Virginia - "Wet" And "Dry," 1909

the 857 licenses to sell alcohol in 1909 was a 60% decrease from licenses in 1901

Source: Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia, Map Of Virginia - "Wet" And "Dry," 1909

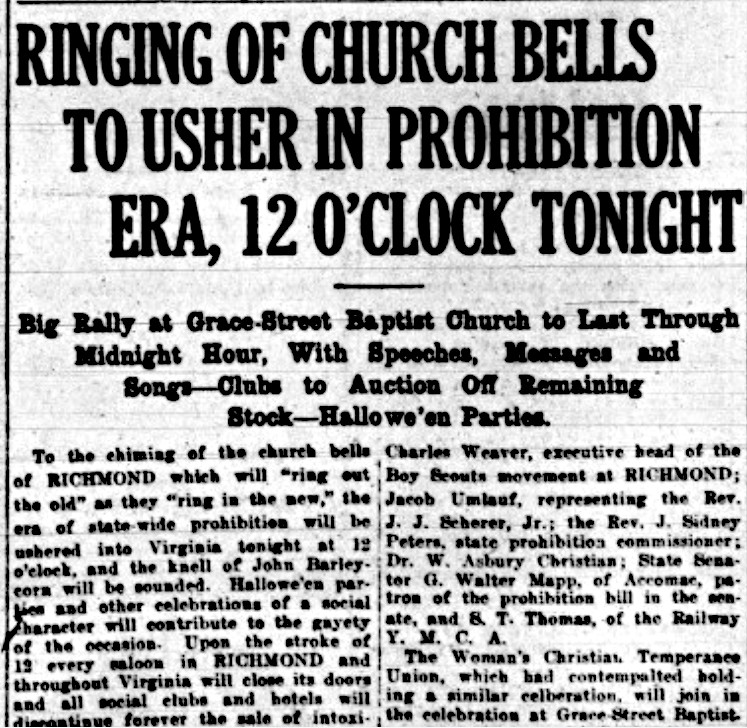

The statewide chapter of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union in Virginia was organized in 1883. In part due to its advocacy, the General Assembly passed the Virginia Prohibition Act on March 10, 1915. Under that law, production and sale of alcohol was prohibited after October 31, 1916. The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, establishing nationwide prohibition, was not ratified until 1919.

Virginia prohibited the sale of alcohol in 1916, two years before ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment

Source: Virginia Chronicle, News Leader and Richmond Times-Dispatch (October 31, 1916)

On October 3, 1933, Virginia voters ratified the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition by a 99,640-58,518 vote. By a slightly larger majority, voters also approved a state-managed liquor control program. Today, the state still controls all sale of distilled spirits through the Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC) stores, or licenses for direct sale of liquor produced at distilleries.1

During Prohibition, Virginia moonshiners manufactured alcohol illegally and distributed it to customers. Franklin County emerged as a major center of distilling and bootlegging, and Roanoke provided a supply of customers.

The grandson of one speakeasy operator in Roanoke recalled how business was conducted there when alcohol was prohibited. The grandfather was a typesetter for a local printer, until he started operating a jitney on Melrose Avenue (US 460). Driving a jitney was the equivalent of being a modern taxi, but the jitney could pick up and discharge riders only along one road. Business might have been light, but the car was primarily useful for driving to and from Franklin County.

In addition to driving a jitney, the grandfather started running a store and gas station. One room in the store was always locked, off-limits to the family's children. At night, customers would be allowed inside and a speakeasy operated in the room where the moonshine was kept.

According to the grandson, during the day customers would pull in for gas and his aunt would go out of the store to the pumps to collect payment. Some customers would tell her that they also needed a pair of shoes. She would go back inside and tell her father, who would get a shoebox from the locked room. For years she thought her father was the smartest man in Roanoke, because he knew without being told the exact shoe size and preferred color for so many different customers.

The grandfather became wealthy. He moved the family from rented space to a nice Victorian house, and purchased two upscale cars.

The speakeasy was the weak point in the scheme. Someone talked, the speakeasy was raided, and the grandfather was ultimately sentenced to six months in jail. He served half that time, and lived the rest of his life on the wealth accumulated from a few years during Prohibition. His grandson concluded the story with:2

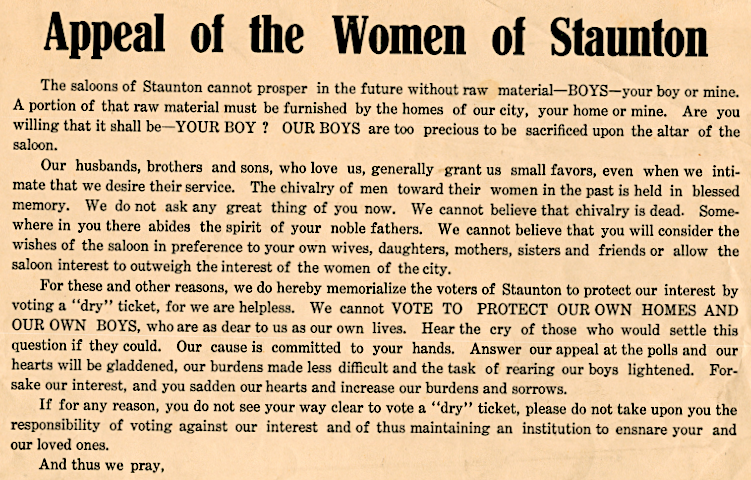

women championed temperance, to redirect the energies of their husbands (and their paychecks) towards the family

Source: Library of Virginia, Appeal of the Women of Staunton