ABC stores are commercial operations, standard self-service customer-based facilities often located in strip malls.

ABC stores are commercial operations, standard self-service customer-based facilities often located in strip malls.

After Prohibition ended in 1933 with ratification of the 21st Amendment, states could authorize sale of alcohol for non-medicinal purposes. Not all states did; Mississippi retained prohibition and was a "dry" state until 1966.

Virginia voters endorsed being "wet" again and approved the repeal of the 18st Amendment by a nearly 2-1 margin in a special election on October 3, 1933. A second issue was on the ballot that day, a choice between continuing prohibition in just Virginia or adoption of a "plan of liquor control." Authorizing sale of alcohol in Virginia also passed by a similar margin.

On October 11, 1933, a 15-person Liquor Control Committee started drafting legislation for the 1934 General Assembly.

The committee endorsed local control so different jurisdictions could determine if they would stay "dry" or allow the sale of alcohol. Focus was on control of managing access to intoxicating drinks to ensure temperance, not generating revenue. The committee also prioritized preventing the return of saloons subsidized by manufacturers seeking to maximize the sale of hard liquor.

The final Liquor Control Committee report in 1934 included:1

The state still has agents authorized to destroy illegal stills, close down unlicensed places ("nip joints") selling alcohol, and impose fines on any of the licensed establishments selling alcohol to underage customers. They work in partnership with local and state police, local sheriff's departments, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms because illegal trade in alcohol is often accompanied by illegal activities involving drugs and firearms.

The state agency now responsible for regulating alcohol, the Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, puts most of its energy into generating revenue. In 2022 the mission statement for the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority was:2

Prior to Prohibition, all the way back into colonial times, Virginia had issued licenses for places to sell all forms of alcohol. One alternative considered by the Liquor Control Committee was for the state to retain a complete monopoly, limiting all retail alcohol sales to state-controlled stores for off-premises consumption. That would prevent a return of the saloon, but allowing package sales only would block customers from having just one or two drinks in a public social setting.

The Liquor Control Committee chose to recommend a middle approach based on the system used in Canada. It proposed sale of wine and beer under different rules that the sale of distilled spirits, including allowing the sale of beer/wine by the drink but not hard liquor. Under the proposal, state-controlled stores would sell wine and liquor but not beer, while private stores licensed by the state would sell only wine and beer.

Sale of liquor by the drink (vs. wine/beer) was viewed as unacceptable because it created the risk of re-establishing saloons:3

The General Assembly established the Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control on March 22, 1934, with three board members appointed by the governor. The first four ABC stores selling liquor and wine opened in Richmond on May 15, 1934. The agency was also tasked with enforcement of state laws controlling the manufacture and sale of alcoholic products, to block moonshiners from producing untaxed and potentially unsafe liquor.

Despite the legal availability of alcohol starting in 1934, moonshining by "whiskey trippers" continued. It was perpetuated by culture and tradition, particularly in the mountains, but primarily because untaxed liquor was significantly cheaper and the market remained for the product. The driving skills demonstrated in "running moonshine" from stills in the Blue Ridge to customers is part of the heritage of NASCAR races today.4

Virginia created a three-tier system separating the manufacture, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages. That approach fragmented the business opportunities, intentionally creating checks and balances that blocked the potential of vertical integration. The three-tier approach also facilitated collection of taxes by the state from manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers.

With a few exceptions, breweries and wineries must rely upon independent distributors to carry alcoholic products to sales outlets. Distributors may not sell directly to customers; instead, they ship beer and wine from warehouses to retail stores.

Today, various forms of wine and beer are sold at convenience stores such as a 7-11, grocery stores, and even gas stations that obtain the required ABC license for off-premise sales. In 2023, Virginia had over 18,000 licensees authorized to sell beer and wine. Stores selling beer and win in Virginia compete for customers by offering different prices, hours of operation, and levels of service.5

Distillers with a Beverage Distilled Spirits Plant permit from the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco and Trade Bureau (TTB) and a distillery license from the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority ship liquor directly to the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority warehouse in Richmond. The state agency distributes products from distilleries to state-owned liquor stores for package sales to the public, and to restaurants and bars with a mixed beverage license allowing liquor-by-the-drink sales to customers.

Distillers may also sell their products to tourists who visit a distillery and may taste a sample there, so long as that product is also sold in the state ABC liquor stores. Distillers must designate someone to serve as an independently operated agent of Virginia ABC and operate a Distillery Virginia ABC store at the distillery. The state agency "contracts out" the operation of a state-controlled liquor store at a distillery, in part to enhance tourism in Virginia.6

When the General Assembly set up the Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control in 1934 (now the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority) and gave it the exclusive right to sell hard liquor directly to the public, the monopoly on sales allowed the state to control prices. Even high-demand products, such as Pappy Van Winkle bourbon, are sold legally in Virginia only in ABC stores at prices set by the state. When demand exceeded supply, customers hunted for stores which had scarce products. A lottery system was set up in 2021 to manage who would be able to purchase products for which demand exceeded supply.

Until restaurants were authorized in 1968 to sell liquor by the drink (one glass at a time), the only legal hard liquor sales in Virginia were bottles handed by ABC clerks to customers standing on the other side of counters in state-owned stores. Private clubs allowed customers to BYOB (Bring Your Own Bottle). Clubs typically charged a fee for pouring drinks rather than selling alcohol "by the drink."

By 2023, self-service stores had replaced all but three counter stores. Two counter stores remained in Richmond and one was in Petersburg. A fourth store in Portsmouth was planned for conversion back into the form of a counter, due to concerns about retail theft and crime in the neighborhood.

into the 1970's, customers went to a counter to order bottles of liquor; there was no self-service

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, Media Library

The Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority issues on-premises licenses restaurants to serve beer, wine, and since 1968 hard liquor. Restaurants have competitive business practices, but the state has limited their ability to sell alcohol at a discount.7

At one time, the Virginia Administrative Code also limited advertising that uses the words Bar Room/Saloon/Speakeasy/Happy Hour, hoping to minimize the potential for excessive drinking. Beer and wine wholesalers were not allowed to deliver beer/wine on Sundays "except to boats sailing for a port of call outside of the Commonwealth, or to banquet licensees," and retail outlets were required to purchase their beer/wine through wholesale distributors that are regulated by the state.8

Billboard advertising of alcohol is now permitted, but billboards:9

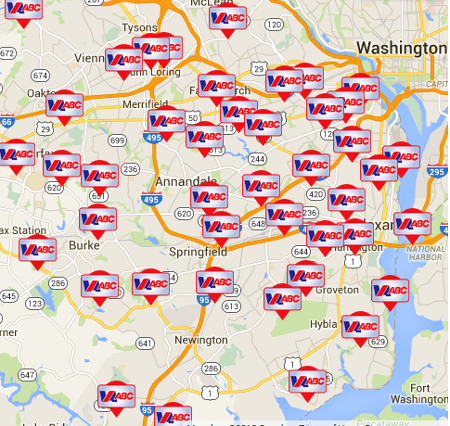

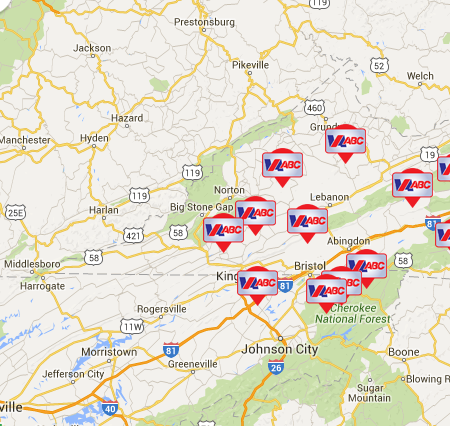

In contrast to retail sales of wine/beer and the sale of hard liquor by the drink in restaurants, the only competition for the sale of bottles of hard liquor in Virginia comes from moonshiners selling untaxed and illegal liquor in plastic one-gallon jugs or even in the classic Mason jar container. No matter what the size of the bottle, the state has a near-monopoly on the legal sale of rum, vodka, bourbon, etc. through 350 state-owned and state-operated ABC stores. Whenever hard liquor is sold in bottles legally in Virginia, that alcohol is sold in a state-run ABC store or in a "distillery store" with an ABC license.

Counties and cities in Virginia can ban the sale of alcohol, but the General Assembly can overturn such limits. The hours of operation, the brands sold, the price of different products, and the locations of ABC stores are state rather than local decisions. Customers who want buy a bottle of bourbon for a modern mint julep (perhaps pretending it was brought by servants on silver platters to their plantation veranda near the boxwoods...) go to a state-run liquor store, or to a state-licensed distillery.

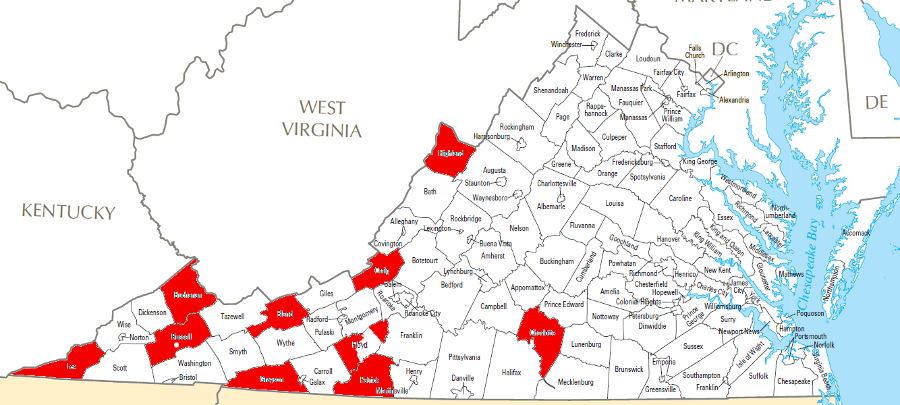

In most cases, it would be a short trip to buy a bottle. The Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control claimed by 2015 that an ABC store was located within a 10--minute drive of 92% of Virginians.10

ABC stores are scattered across Northern Virginia in all jurisdictions, but Lee County forbids sale of alcohol - so someone living at Cumberland Gap (near Middlesboro, Kentucky) would have to drive over an hour to the ABC store in Big Stone Gap (in Wise County) or in Gate City (in Scott County) to purchase a bottle of hard liquor legally in Virginia

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, ABC Store Finder

All ABC stores used to be closed on one day each year when elections were held. Stores shut down on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, in addition to the traditional holiday closings on Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, New Year's Day and Easter. Sales stopped because the state had decided that bottles of hard liquor and elections do not mix. Closing the ABC stores was expected to reduce the chance that modern voters might be swayed by liquor.

That first Tuesday after the first Monday in November is always election day in Virginia, every year. In odd-numbered years, all 100 seats for the House of Delegates are on the ballot. Every 4 years in odd-numbered years, voters also make decisions on all 40 seats for the State Senate. In even-numbered years, registered voters can choose one of the 11 different Representatives who serve in the US Congress. Every 6 years, the race for one U.S. Senate seat is on the ballot.

The now-repealed election day closure of ABC stores contrasted with the confluence of drinking and voting in colonial elections. In the 1700's, candidates in Virginia offered alcoholic punch to voters throughout election day.

The free drinks offered to all voters gave rural farmers a rare opportunity to gather, see their neighbors, and party at the expense of the candidates. Voting in Virginia was by "open outcry" (viva voce), not by secret ballot, until after the Civil War. Voters would approach the sheriff and announce their decision, and candidates and onlookers heard each vote announced. Candidates who failed to provide any alcoholic rewards for participating in the process could be punished by the voters.

James Madison lost only one election in his life, in 1777, when he failed to offer Orange County voters any refreshments on election day. George Washington was rejected by the voters of Frederick County in 1755 when he first sought election to the House of Burgesses. One reason for the rejection was his opposition to local taverns selling alcohol to the Virginia Regiment troops. Washington led the militia from his headquarters in Winchester at the start of the French and Indian War, and his major discipline challenges were exacerbated by the easy availability of booze.

In George Washington's second attempt at office in 1758, he made sure to treat the voters liberally to honor their participation in the electoral process and to obtain their support. He provided about 150 gallons of beer, hard cider, punch, and rum to entertain 391 voters. Simple math suggests that they drank heavily throughout the day, or shared with others who took advantage of Washington's hospitality.11

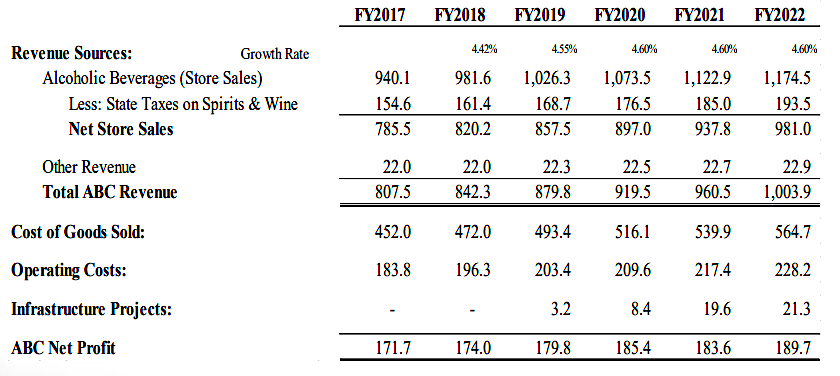

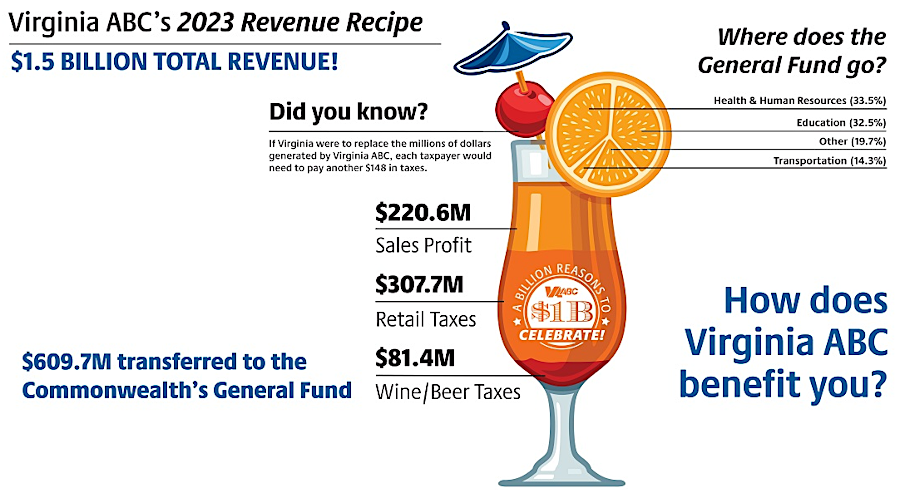

The liquor monopoly generates substantial revenues for the state. The state excise tax is 20% on distilled spirits and 4% on beer/wine, and the ABC stores also charge 5% sales tax. In 2018, the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control was reconstituted as the Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, giving it greater flexibility in running a for-profit operation. That year, for the first time the state generated over $1 billion in revenue from the ABC stores where hard liquor was sold.

Alcohol sales in FY2019 generated $500 million in state revenue - $198 million in profits from retail sales at ABC stores, $223 million in taxes on alcohol sold in those stores, and $80 million from taxes on wine and beer sold in other stores. That reflected a steady increase due to opening more stores, and keeping stores open for longer hours (including Sunday mornings).12

profit and loss projections assume a steady growth in sales exceeding 4%, in part by opening eight new stores each year

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, Virginia ABC

Overview of Operations and Budget

The top products sold in ABC stores (based on total dollars, rather than total volume) have changed over time:13

2022 Rank | 2021 Rank | 2020 Rank | 2019 Rank | 2018 Rank | 2017 Rank | 2016 Rank | 2015 Rank | 2014 Rank | 2013 Rank | 2012 Rank | Brand | Product Category |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 21 | 40 | 40 | Tito's Handmade | domestic vodka |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 11 | Hennessy VS (1) | Cognac\Armagnac |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Jack Daniel's 7 Black | Tennessee whiskey |

| 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 17 | - | Patron Silver | tequila |

| 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | Jim Beam | straight bourbon |

| 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 22 | Crown Royal | Canadian whisky |

| 7 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | Maker's Mark | straight bourbon |

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Jameson Irish | Irish whiskey |

| 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | Fireball Cinnamon | Canadian whisky |

| 10 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 14 | Grey Goose | imported vodka |

| 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | Smirnoff 80 | domestic vodka |

| 12 | 12 | 14 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 39 | - | - | - | Crown Royal Regal Apple | Canadian whisky |

| 13 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 23 | 27 | 37 | 43 | - | - | Woodford Reserve | straight bourbon |

| 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | Bacardi Superior | domestic rum |

| 15 | 18 | 21 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 39 | 45 | 48 | 50 | - | 1800 Silver | tequila |

| 16 | 17 | 15 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 14 | - | Jose Cuervo Especial Gold | tequila |

| 17 | 16 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 8 | 7 | Captain Morgan's Spiced | rum |

| 18 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | Absolut | imported vodka |

| 19 | 19 | 43 | 35 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Jose Cuervo Especial Silver | tequila |

| 20 | 30 | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Lunazul Blanco | tequila |

| 21 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - | Evan Williams Black | straight bourbon |

| 24 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | Pinnacle | imported vodka |

| 32 | 26 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 8 | Aristocrat | domestic vodka |

In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2012, three of the four top-selling ABC stores were located in Virginia Beach - a key destination for tourists. Store No. 256, in the Hilltop North Shopping Center, was the "king of booze" in Virginia:14

The top-ranked store in 2012 was still the biggest seller in 2024:15

If the state tries to make too much profit from its retail markup, customers can not go to a competitor down the street. Because the state ABC stores are the only legal places for selling hard liquor by the bottle, customers must travel across the state line to find a different price on hard liquor.

To limit that competition, Section 3VAC5-70-10 of the Virginia Administrative Code prohibits importing more than one gallon of alcoholic beverages from outside the state or from military posts with PX stores. Many Virginians working in Washington DC who plan to "stock up with cheap liquor for a party" have heard rumors of ABC agents staking out DC liquor stores, then tailing cars with Virginia plates back across the Potomac River to enforce the one-gallon import limit.

In 2010-11, Governor Robert McDonnell tried to abolish the system of state control and privatize alcohol sales, eliminating the state monopoly on the sale of hard liquor. In the original proposal, 1,000 retail licenses would have been auctioned, tripling the number of outlets in Virginia for liquor sales.

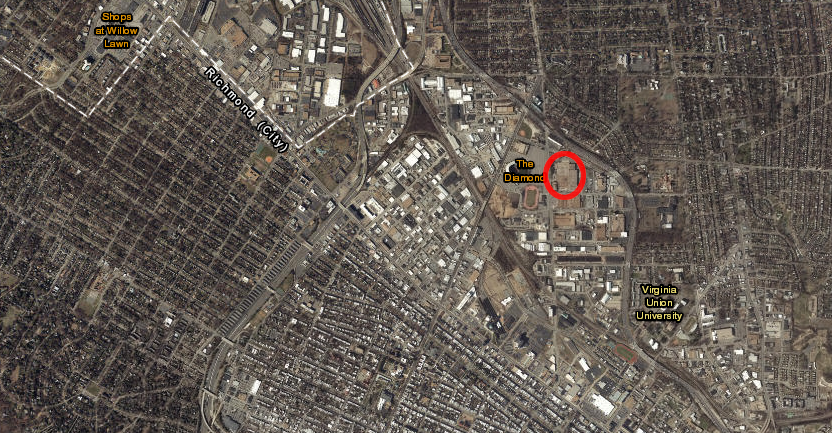

Wholesale operations would also be shifted to the private sector, and the state would sell the main ABC warehouse in Richmond. It had been located at the intersection of Harrison and West Broad streets (known locally as "Alcohol and Broad"), then moved in 1971 to 2901 Hermitage Road.

The governor claimed privatization would generate $500 million, which would be used to finance transportation projects.16

the central warehouse ships bottles of hard liquor to the 350 or so local ABC stores

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, Image Bank

The governor's proposed new tax on restaurants selling alcohol was unpopular among anti-tax conservatives in the General Assembly. When the governor modified his plan and dropped that tax, outside reviewers determined that privatizing the entire ABC operation would not be revenue-neutral. After the one-time initial surge of funding from selling 1,000 licenses, the state would end up receiving $47 million less annually.

In the end, the General Assembly killed the proposal in February, 2011 without a hearing. The governor found a different way to raise taxes that financed his transportation agenda in 2013. Five years later, the 2018 General Assembly authorized sale of the ABC headquarters and warehouse in Richmond. The state decided to move the facilities to Mechanicsville in Hanover County, near the intersection of pole Green Road and I-295.

The agency was cooperative. The shift in location gave Alcohol Beverage Control the opportunity to implement modern technology in a four new warehouse totaling 778,000 square feet, plus a new office building. The most important factor in relocation, however, was to free up the land occupied by the warehouse and offices at 2901 Hermitage Road.

Making it available provided greater flexibility for replacing the baseball stadium next door, built in 1985 and known as The Diamond. The Atlanta Braves moved Richmond's AAA minor league team to Georgia in 2009, after playing for 43 years in Richmond. Gwinnett County built a new ballpark after Richmond could not commit to replace The Diamond. After recruiting a AA team known as the Flying Squirrels, the city negotiated a deal for them to stay in Richmond for 30 years if a new stadium was constructed.

Virginia Commonwealth University and the Flying Squirrels developed a plan to build a new $55 million shared stadium. The university would also construct an Athletics Village, with sports medicine and other academic programs.

The General Assembly supported the plan by moving the Alcohol Beverage Control to Hanover County and giving Virginia Commonwealth University first rights to purchase the state-owned land at fair market value. The university purchased the 20-acre site of the former ABC headquarters/warehouse at 2901 Hermitage Road in 2022 for $16 million, a price that was below market value but had been established previously by the General Assembly. That purchase completed the university's assemblage of different parcels totaling 41 acres, costing $39 million total, to create the Athletics Village.17

moving the Alcohol Beverage Control headquarters on Hermitage Road made space for replacing The Diamond baseball stadium

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia has permitted sale of liquor by the drink in food establishments (as opposed to whole-bottle sales in ABC stores) only since 1968. Restaurants and the entertainment industry lobbied for that change in the 1960's. Liquor by the drink eliminated the "brown bag" requirement that customers join a private club and bring their own bottle to the restaurant (typically in a brown paper bag) in order to enjoy a drink before a meal.

State regulations known as the Mixed Beverage Annual Review (MBAR) require that restaurants serving liquor must earn at least 45% of their revenue from food sales. In addition, restaurants must sell at least $4,000 each month of food prepared and consumed at the restaurant. Prepackaged snacks and take-out food itens do not qualify, and beer and wine sales are not assesed as part of the 45% minimum.

Those thresholds are designed to limit the creation of pre-Prohibition "bars" where customers just drink. The 12,000 members of the Virginia Restaurant, Lodging, and Travel Association (VRLTA) are split on efforts to modify the limit.

The large chain restaurants typically are supporters, since their business model includes a high percentage of food sales. Especially in tourist areas, many small restaurants would prefer to lower the percentage; they want the opportunity to serve casual customers who do not sit down for a meal. Some restaurants want to sell more high-priced drinks, offering specialty liquors and cocktails, but the extra revenue from alcohol sales makes it more difficult to meet the 45% minimum from food sales.

Efforts to change the Mixed Beverage Annual Review (MBAR) regulations in the 2025 session of the General Assembly were blocked because a fish and chips shop in Portsmouth had filed a lawsuit claining the regulations were unconstitutional. It was customary for the legislature to avoid changing state laws while they were being challenged in court; modifications were traditionally made after judges had made a decision.

In the meantime, a member of the Danville city council had to wait. He highlighted how the requirement to generate a substantial percentage of income from food sales was a problem in his city, since North Carolina businesses selling alcohol across the state line operated under less-restrictive requirements:18

Not every community in Virginia allows alcohol sales. In some rural Virginia counties, there have been odd alliances of religious opponents opposed to the use of alcohol and moonshiners who wanted to protect their business from legalized competition. Since 1968, however, the lure of additional tax revenue from ABC payments and especially from restaurants selling liquor by the drink has overcome the opposition in nearly every jurisdiction.

top-selling products at ABC stores change a little every year, as customer tastes change

Source: Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control, 2015 Annual Report and Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, 2019 Annual Report

100% of the cities are "wet," reflecting the influence of the hospitality industry in urbanized areas. Between 2001-2015, the number of "dry" counties changed from 35 to 8. In 2016, Russell County voters approved sale of alcohol in the Town of Lebanon.

In 2019, the General Assembly changed the rules. It made all counties "wet," starting in 2020, unless local voters in a referendum acted to keep it "dry."17

At the time, the remaining 100% "dry" counties were Appomattox, Bland, Botetourt, Buchanan, Campbell, Carroll, Charlotte, Craig, Dickenson, Floyd, Franklin, Giles, Grayson, Green, Halifax, Henry, Highland, King William, Lee, Louisa, Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, Patrick, Pittsylvania, Pulaski, Russell, Scott, Smyth, Surry, Tazewell, Warren, Washington, Wise, and Wythe.19

officially-dry counties are concentrated in southwestern Virginia, but all counties on the I-81 corridor are "wet"

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS) National Atlas, County Map

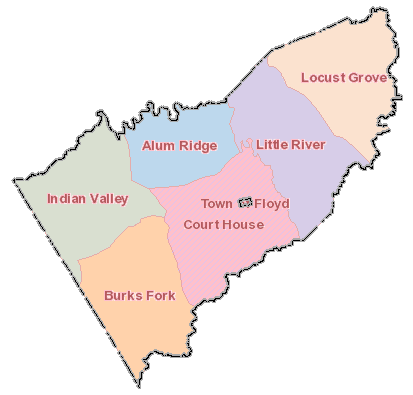

Prior to the General Assembly changing the rules in 2019, selected portions of "dry" counties managed to get approval to serve alcohol. Some used a local referendum, while others got members of the General Assembly to sponsor special legislation that created an exemption.

The Little River District of Floyd County, one of the magisterial districts in the county, went "wet" in 1996. Voters in that district had rejected alcohol sales in a 1991 referendum, but changed their mind five years later. Only one restaurant, Ray's, sold liquor-by-the-drink consistently after the vote.

In 2013 entrepreneurs creating a legal moonshine distillery, Five Mile Mountain, discovered the limits on alcohol sales in Floyd County would prohibit serving their product to customers. The distillery owners partnered with local restaurants seeking the opportunity to sell alcoholic drinks to diners, and arranged for a referendum to authorize liquor sales in the Courthouse District (including the town of Floyd with its restaurants). In 2014, voters approved liquor sales in the Courthouse District.

That decision led to several restaurants getting ABC licenses for liquor-by-the-drink sales. It also led to the opening of the first ABC retail store in Floyd County.

Under state law, restaurants must purchase their liquor from ABC stores for resale to customers. Food and all other items used in restaurants/bars can be purchased directly from wholesalers, but in Virginia hard liquor must be bought at the ABC store.

In Floyd County, the restaurant Ray's had to drive to an ABC store in another county to purchase its liquor. When the voters in 2014 authorized alcohol sales in the Courthouse District as well as the River District of the county, the state expected a significant increase in the number of Floyd County restaurants obtaining ABC licenses to sell liquor by the drink.

The Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control chose to open an ABC store to supply hard liquor to those restaurants, and to sell directly to individuals as well. When that store opened (in the Courthouse District) in 2015, people could purchase a bottle of hard liquor in Floyd County legally for the first time since 1916.20

in Floyd County, only the Little River district and the Courthouse district (including the Town of Floyd) have authorized sale of liquor-by-the-drink

Source: Floyd County, iGIS

In 2017, voters in Wise County approved a referendum to allow sale of wine and beer on Sundays, and Boone's Mill in Franklin County authorized restaurants to sell alcohol. In 2018, voters in the Town of Richlands in Tazewell County also approved the sale of mixed alcoholic beverages in restaurants by a 60%-40% majority.21

When local voters stayed reluctant to authorize sale of liquor by the drink, some entrepreneurs bypassed them by going to the General Assembly to gain approval. Legislators who did not live in that jurisdiction carried the bills granting exemptions, so local voters could not retaliate at the polls. The presumption is that the local legislator who may have wanted to do a favor for a business did some horse-trading with a legislator who lived elsewhere, providing support for some other legislation in exchange.

The 2019 legislation finally deleted that section of the Code of Virginia which included the following specific authorizations for 31 places where mixed drinks could be sold within a "dry" county:22

Kanawha Valley Arena Resort - exception (xxvii) - qualified as "property fronting Kanawha Ridge Road, located within approximately 700 feet of Route 638, and operated as a resort in Carroll County as of December 31, 2007"

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The "town incorporated in 1894 consisting of 1.9 square miles and, prior to the town's incorporation, known as Guest Station" - exception (xxvi) - is Coeburn in Wise County. The former Woodberry Restaurant, which was located within one-quarter mile of Mile Marker No. 174 on the Blue Ridge Parkway - exception (iv) - advertised that customers should imagine "strolling around the beautiful grounds after a perfectly mixed cocktail at our bar ."23

selling mixed drinks on the Blue Ridge Parkway in Floyd County was a marketing opportunity for the Woodbridge Restaurant

Source: Woodberry Inn, Imagine

In 2020, when Governor Northam issued Executive Order 53 closing all dining and congregation areas in restaurants, dining establishments, food courts, breweries, microbreweries, distilleries, wineries, tasting rooms, and farmers markets during the COVID-19 pandemic, he declared beer, wine, and liquor stores to be "essential retail businesses" which could stay open.

That ensured the state would continue to receive revenue, at a time when economic disruption was forcing dramatic budget reductions. However, purchases by licensees such as restaurants dropped to zero, since those facilities were closed. Such sales typically generated 20% of the revenues.

Leaving the stores open also reflected customer priorities. Had the ABC stores closed, Virginians would have driven across the state border and purchased alcohol in the District of Columbia or in other states.24

Despite the pandemic, the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority had a record year for profits. Sales to bars and restaurants declined as those outlets closed, then recovered as the state increased flexibility and allowed customers to order mixed beverages with takeout orders. For the 2019-20 year as a whole, sales to licensees declined 19%. However, retail sales grew 18%.

Of the total increase of $117 million in sales, $18 million could be attributed to the 12 new stores. Retail sales had already increased 7% before the pandemic, in part because of more careful selection of products being stocked. A major factor was the decision during the pandemic of customers to consume more alcohol.25

The pattern of increased consumption continued. Revenue increased over 10% between July 1, 2020-June 30, 2021, reaching $1.4 billion. The General Fund of the state budget received $616.4 million in profits. Sales to licensees - restaurants and bars - were down 15% due to the continued effects of COVID-19 pandemic, but consumer purchases steadily increased.

Standard sales techniques that increased profits included opening more stores, expanded operating hours, pricing products with sales and discounts, and offering in-store tastings. The Chief Executive Officer of the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority credited the General Assembly's decision in 2015 to allow the organization to operate more like a business:26

After the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control became the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, the Board of Directors prioritized investment in new information technology and a new warehouse for distribution. Sales increased in FY23 to $1.5 billion, and sales volume grew from 6.32 million cases to 6.46 million cases. Overall revenue to the state reached a new record of d $610 million, counting profits from liquor sold through the state monopoly, sales taxes collected at the state liquor stores, and taxes on wine and beer.

However, profits from retail sales declined in FY23 due to a 7.3% increase in operating expenses. The retail sales portion of the revenue transfer to the state treasury declined from $229 million in 2021 to $221 million in 2023, despite selling an additional $100 million in products and a 4.9% revenue growth in FY23.

in FY23, profits from liquor sales dropped to $221 million as cost increases offset a 4.9% growth in revenue

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, About Us

In 2023, Governor Youngkin proposed a reduction in the authority's expenses so the state would get more net revenue. The independent Board of Directors initially rejected that proposal. Since the Authority was self-funded from its sales, it did not need to comply with the governor's proposal. However, the Governor directed the board members to vote again, after chastising them for neglecting their duties.

For the FY25-26 budget, Governor Youngkin projected that state alcohol sales would increase revenue by 5%. As the General Assembly was considering the FY25-26 biennial budget in February, 2024, the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority issued a report that anticipated lower FY 25 and FY26 revenues, since FY24 revenue was predicted to grow by just 1.4%. Revenue from liquor sales increased on average by just 1.7% in FY24 in the other 17 "control states." Customers were buying less, and liquor suppliers decreased prices in response.

The Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority projected transferring $33.8 million less than initially planned in FY25 and $48.2 million less in FY26.

Despite the lower sales projections from the state agency, the General Assembly adopted Governor Youngkin's optimistic estimates for the FY25-26 budget. Before the governor could sign it, the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority issued an even lower revenue projection. The estimate predicted a FY25 shortfall of $44.1 million (vs. the earlier $33.8 million). In FY26, the predicted shortfall grew to $66 million (vs. the earlier $48.2 million).

Rather than see Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority revenue grow 5% in 2025 and another 5% in 2026, by October 2024 the state agency predicted 0% growth in 2025 and 1% growth in 2026. Customers were buying less alcohol, perhaps in part due to competition from cannabis, and choosing lower-priced items when making purchases at ABC stores.27

Like all retail businesses selling high value products, the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control experienced theft. In 2022, the director of retail operations discovered that $1.7 million in inventory had disappeared from the central warehouse in Richmond as the agency was implementing its new distribution center in Mechanicsville. In addition, a flaw in the cash register system allowed employes at seven retail stores to steal liquor.

The director of retail operations ended up filing a "whistleblower" lawsuit. She claimed top ABC officials had retaliated against her, and covered up the problems at the Mechanicsville distribution center. One problem was a broken scale used to weight shipments; it was essential for determining if bottles had been stolen and cartons then resealed. Distillers were paid only after their products were shipped from Mechanicsville, so theft before distribution cost distillers money as well as the state agency.

Several top officials at the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority resigned in 2023, including the Chief Executive Officer. None of the personnel changes indicated the board appointed by the Governor had any issues with those executives.

In 2024, over 30,000 bottles worth over $1.5 million were stolen from ABC stores. Organized crime gangs were stealing high-value products such as bottle of cognac from the shelves in Northern Virginia. Statewide, in 2024 64% of items stolen from the state-run stores were tequila. In Richmond, nearly 50% of the police department's shoplifting cases were thefts of liquor bottles from the store shelves.

Unlike electronics and other expensive products in many retail stores, ABC stores did not place items prone to theft inside locked cases. The store near Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond was converted from self-service to counter sales, and it quickly fell off the list of high-theft sites.

Police in Virginia Beach reported that over 20% of their shoplifting calls came from from ABC stores. To reduce the significant drain on local resources, the police chief asked that ABC's special agents take on primary responsibility for dealing with shoplifting cases.

A news release issued in mid-2023 said the percentage of inventory "shrink" (loss of inventory through process control failures, theft and damages) as far below the national average of 1.4% in fiscal year 2021:28

| Year | Total Shrink | Gross Alcohol Sales | Percent of Sales |

| FY 23 as of 04/30 | $1,127,449 | $1,198,907,081 | 0.094% |

| FY 22 | $1,528,488 | $1,369,654,840 | 0.112% |

| FY 21 | $2,828,253 | $1,329,826,387 | 0.213% |

| FY 20 | $2,205,666 | $1,173,498,688 | 0.188% |

the ABC store in Staunton still includes the traditional glass bricks, but is now self-service

The 2021 General Assembly loosened restrictions on alcohol consumption by authorizing creation of up to three Designated Outdoor Refreshment Areas (DORA's) in a jurisdiction. They were intended to facilitate towns/cities creating entertainment districts, boosting economic activity by allowing customers to wander outside while carrying alcoholic drinks:29

Danville was an early adopter of the Designated Outdoor Refreshment Area flexibility. It hoped to turn the River District into a place where customers could gather and explore food and entertainment venues without having to stop at barriers to finish a beer, glass of wine, or cocktail. Permanent city restaurants would benefit from increased business, as opposed to beer trucks. Though Danville may never rival Bourbon Street in New Orleans, it could offer the same level of flexibility and festival atmosphere for outdoor drinking.

Downtown Roanoke Inc. was one of the first organizations to use a DORA license. The 2021 GO Fest event was held in the city's downtown. It previously had been held at River's Edge Park, with beer trucks brought in to provide alcohol. In a DORA location, temporary beer trucks would compete with existing business selling alcohol, and state regulations required that only permanent retail on-premises licensees could sell alcohol. Downtown Roanoke Inc. used the DORA license so that existing restaurants could sell alcohol to customers and allow them to leave the premises, though drinkers had to remain within the boundaries of the Designated Outdoor Refreshment Area.30

The three-tier distribution system for beer, requiring brewers to sell to distributors who then sold to retailers, was modified when on-site sales were permitted to breweries. The 2023 General Assembly loosened the system again. The legislature authorized creation of the Virginia Beer Distribution Company as a state agency within the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The new agency created an online portal, allowing retailers to go to one website to purchase beer from craft breweries which had not signed a distribution agreement with another company.

The new law allowed 300 craft breweries in Virginia to self-distribute about 500 barrels (1,400 kegs) each directly to restaurants and other customers each year. The law also closed a loophole through which some almost-direct sales were occurring. Brewery owners were not allowed to own a distribution company, but spouses or family members had been able to own one. The 2013 Beer Industry Limited Distribution Act banned future such "arms-length" arrangements.

The creation of the non-profit Virginia Beer Distribution Company (VDBC), the first state-operated beer distributor in the United States, was modeled on the earlier creation of the Virginia Wine Distribution Company. Both the Virginia Craft Brewers Guild and the Virginia Beer Wholesalers Association supported the 2023 law. By expanding self-distribution, craft breweries were expected to find more markets for niche products which distributers found unprofitable to handle.

The creation of a specialized distributor for craft breweries was designed to assist small operations while maintaining the three-tier distribution system. Breweries producing more than 500 barrels a year were expected to sell through standard distribution channels. The wholesale distributors prioritized doing business with larger breweries, and creating a state distribution company reaffirmed their state-guaranteed business model without impacting wholesale profits.

In January, 2025 the Thin Blue Line bewery in Virginia Beach became the first to distribute beer to restaurants and retailers through the Virginia Beer Distribution Company. The head of the Virginia Beer Wholesalers Association highlighted that craft breweries:31

former Bowman distillery - and former Wiehle town hall/Methodist church - at Sunset Hills farm (now Reston)

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Bowman Distillery 029-5014

the 2018 General Assembly authorized sale of the Alcohol Control Board headquarters and warehouse on Hermitage Street in Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

new headquarters and warehouse in Henrico County near Mechanicsville

Source: Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority, Media Library and ESRI, ArcGIS Online