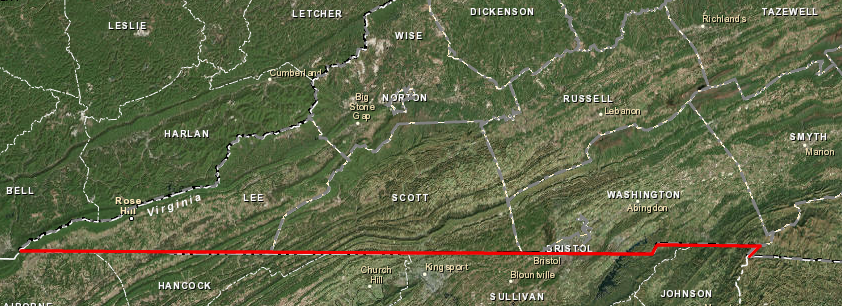

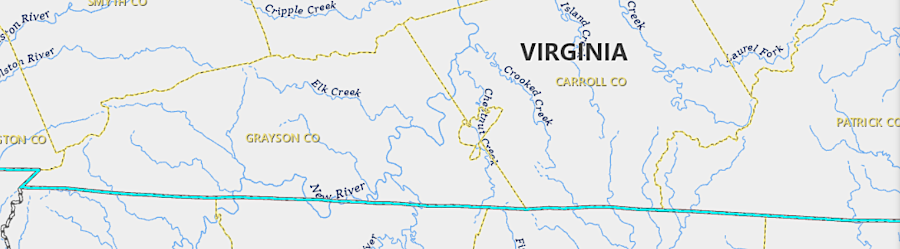

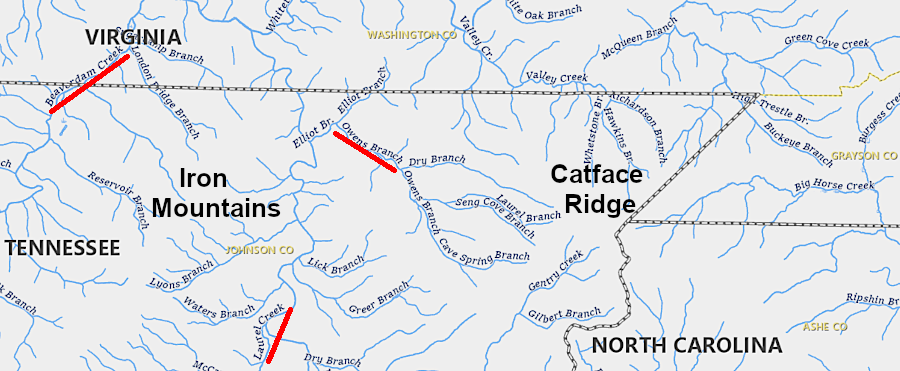

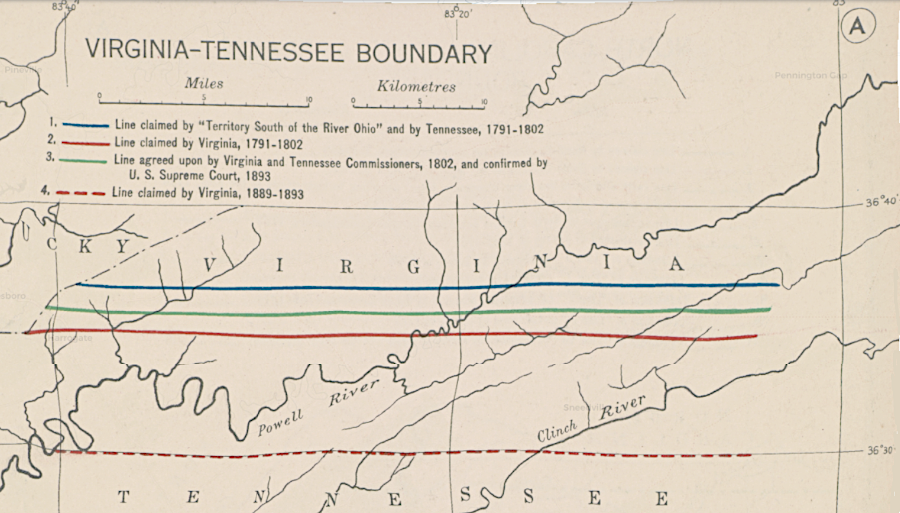

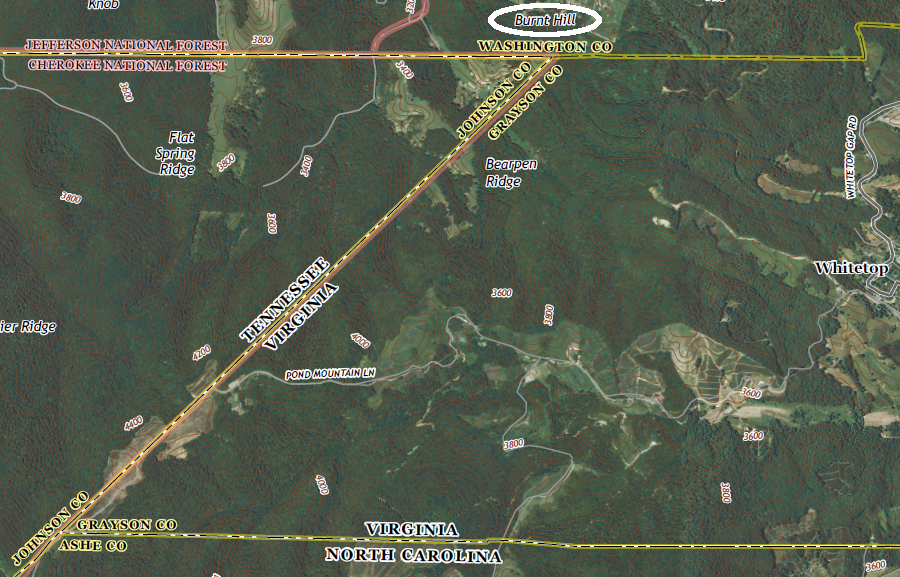

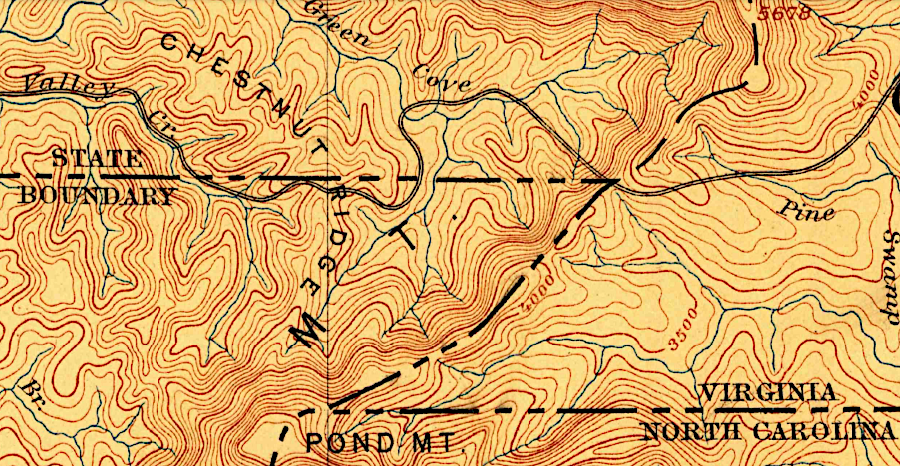

the Tennessee-Virginia border today has evolved from the 36° 30' parallel of latitude defined in 1665 to separate Virginia-North Carolina

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Tennessee-Virginia border today has evolved from the 36° 30' parallel of latitude defined in 1665 to separate Virginia-North Carolina

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The modern Virginia-Tennessee boundary line was surveyed originally as a border between North Carolina and Virginia.

Tennessee officials were not involved in making the first boundary surveys because there was no State of Tennessee until 1796, when the western part of North Carolina became a new state. Tennessee officials had their greatest impact on the Virginia-Tennessee border in 1802, and then later lawsuits and political compromises finalized the straight lines, notches and zig-zags in the boundary.

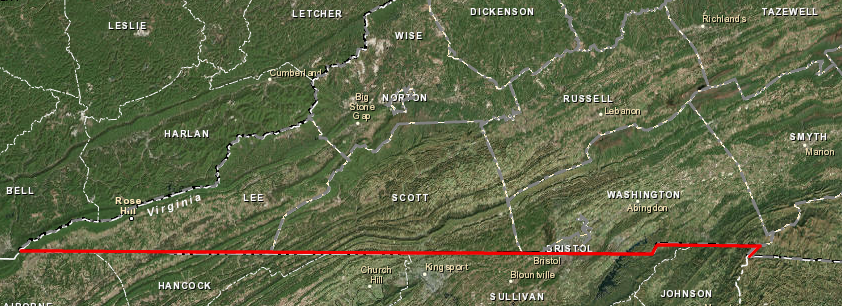

The first key decision shaping the modern Virginia-Tennessee border was made in 1629. King Charles I initially gave all the land between the 31° and the 36° parallel of latitude to his Attorney General, Sir Robert Heath, and named it Carolana. In 1645 during the English Civil War, Parliament revoked the grant and Heath died in exile.

Sir Robert Heath's claim to Carolana disappeared, but the boundaries defined in the 1629 patent were still remembered. In 1663, Charles II re-started the distribution of land by royal fiat by granting the Charter of Carolina to reward eight supporters who helped him during the English Civil War.

the Tennessee-Virginia border started as the 1629 boundaries of the grant of Carolana between the 31° and the 36° parallel of latitude to Sir Robert Heath

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1665, Charles II modified the North Carolina charter to grant the new colony control over all of the Albemarle Sound by moving the boundary a half-degree of latitude (approximately 34 miles) north to the 36° 30' parallel. In theory, many years later the Virginia/Tennessee border was supposed to follow the westward extension of that 1665 boundary, the 36° 30' parallel of latitude separating Virginia from North Carolina.

a 1665 land grant by Charles II to eight Carolina proprietors, using the the 36° 30' parallel, shaped the ultimate Tennessee/Virginia and Tennessee/Kentucky borders

Source: Library of Congress, State claims, 1776-1802 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1917)

Surveyors first started to mark a line along that 36° 30' parallel in 1710. Defining the boundary would clarify which colony could sell land and collect taxes there. The planned survey project failed completely.

Philip Ludwell and Nathaniel Harrison, commissioners from Virginia, met the two North Carolina Commissioners but they never started to survey a line. North Carolina's Edward Moseley accused the Virginia surveyors of bringing inaccurate instruments. In turn, the Virginians accused Moseley of having a conflict of interest because he speculated in lands along the border. Both sides were correct.

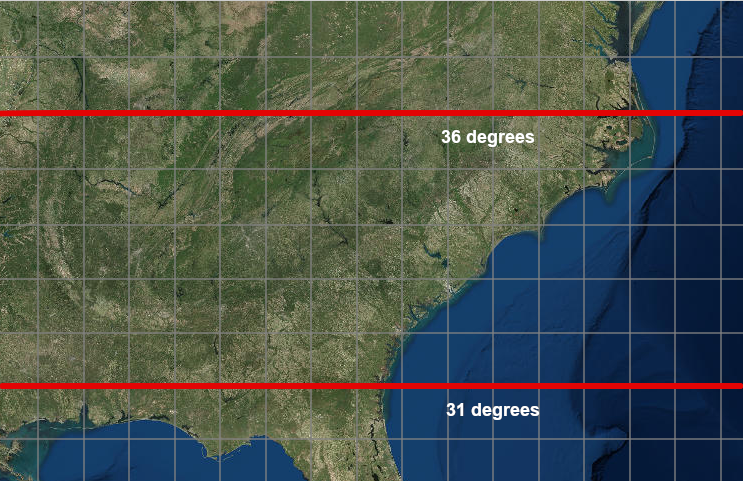

The "dividing line" survey of 1728 was more successful. The time in the field completing the survey was well-documented by William Byrd II in public and private records. That survey marked the boundary between Virginia-North Carolina from the Atlantic Ocean inland, going all the way to what the Virginians called the Dan River and the Carolinians called the Fitzwilliam River.

The North Carolinians quit earlier than the Virginians, claiming there was no reason to push the line far west of existing settlements. The Virginians were more optimistic about the speed of settlement expanding westward, and continued to survey the colonial boundary line. The Virginia survey team stopped at Peters Creek in 1728. They had crossed the Dan River/Fitzwilliam River four times, but stopped short of the point further west where that river crossed the border yet one more time.

the Virginia surveyors continued on to Peter's Creek in 1728, finally stopping east of where the Dan River first crosses the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

William Byrd II correctly anticipated the willingness of the Governor of Virginia and his Council of State to support westward expansion of settlements. In 1745, James Patton obtained a 100,000 acre land grant. In 1749, the Loyal Land Company was given 800,000 acres of land in Southwestern Virginia.

Colonial officials were willing to facilitate land speculation, in part to enhance the opportunity for favored members of the gentry to get even richer and in part to expand the number of English settlers in the western borderlands. Increasing the number of loyal (and Protestant) settlers would provide greater security against French (and Catholic) land claims to the Ohio River Valley, and would also create an early warning system against Native American raids.

The grant to Patton, and other similar large grants, created a need to define where Virginia's legal authority ended on the southern edge of the colony. One of the surveys for a tract within Patton's grant was for a site known then as Sapling Grove, and today as Bristol in both Virginia and Tennessee. Another tract, surveyed within Patton's 100,000-acre grant for Edmund Pendleton, was on Reedy Creek at a location that today is completely within Tennessee.

In 1749, Virginia and North Carolina appointed a new set of commissioners to survey the boundary. Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry from Virginia and North Carolina commissioners Daniel Weldon and William Churton managed to survey another 90 miles west from Peters Creek.

The instruments used in 1749, though satisfactory this time to the North Carolina commissioners, were imperfect. Accounting for the variation of magnetic north required constant refinement as the surveys moved westward. What was intended to be a straight line along the 36° 30' parallel drifted nearly five miles north. The tilt of their survey line becomes more obvious today as the line moves further west.

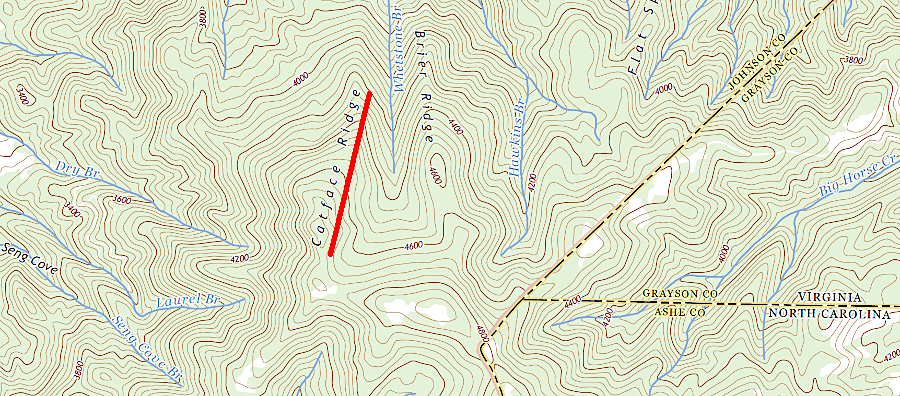

perhaps due to incorrect adjustments for magnetic declination, Fry and Jefferson's survey line tilted towards the north as they moved westward from Peter's Creek in 1749

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

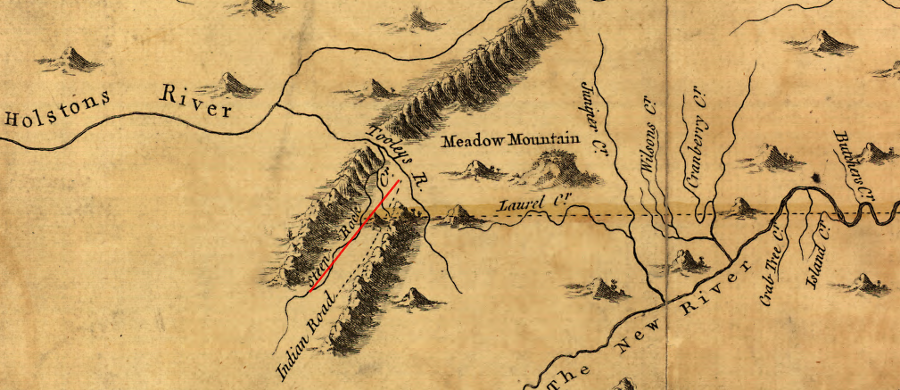

The Virginia and North Carolina survey teams stopped at what they called "Steep Rock Creek." Based on the map published by Fry and Jefferson in 1751, that stream was a tributary of the Holston River flowing westward towards the modern town of Damascus. The surveyors had crossed the watershed divide between the New River and the Tennessee River, which at the time was also called the Cherokee River.

Exactly where the surveyors stopped in the Tennessee River watershed can be debated. Stream names have changed since 1749. Today, there is no Steep Rock Creek in Virginia, North Carolina, or Tennessee.

The stream called "Steep Rock Creek" could be what today is named the Owens Branch tributary of Laurel Creek, if the surveyors crossed westward over Catface Ridge and then stopped. If they went further west, "Steep Rock Creek" is probably what is now called Laurel Creek, flowing north through Damascus into the South Fork of the Holston River.1

the 1749 survey by Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry ended at "Steep Rock Creek" (perhaps modern Laurel Creek, east of Damascus)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina.; US Geological Survey, Abingdon, TN 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1891) and Grayson NC 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2022)

If Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry surveyed westward across the Iron Mountains and then decided to stop in the next stream valley, then "Steep Rock Creek" could be today's Beaverdam Creek.

Steep Rock Creek could be Beaverdam Creek, west of the Iron Mountains

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Not only has the name "Steep Rock Creek" disappeared from modern maps, but "Laurel Creek" has been applied to multiple streams in the area. The Laurel Creek named by Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry as they neared the western endpoint of their 1749 survey may be a tributary of the stream now called Big Horse Creek.

the "Laurel Creek" on the 1749 Fry/Jefferson survey may be an east-flowing tributary of what is now called Big Horse Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online and US Geological Survey, Grayson, NC 1:24,000 scale topographic map (2022)

For two decades after 1749, Virginia and North Carolina legislators had no reason to appropriate the money required for another survey to extend the colonial boundary from its western end at Steep Rock Creek. Settlement in the far western edges of the colonies was slowed by the distance from the port cities on the Eastern seaboard, and by resistance from the Cherokees.

Today's Virginia-Tennessee boundary was defined only after Virginia declared independence from England in 1776 and became a state.

There were multiple and conflicting surveys before final resolution. North Carolina laid claim to lands extending to the Mississippi River, and at one point included territory which some thought was part of Virginia. In 1789, North Carolina ceded its western lands to the Continental Congress. Virginia ended up disputing the boundary with North Carolina, then with the Federal government which controlled the Southwest Territory. The southwestern boundary of Virginia was not fixed until after the Southwest Territory became the State of Tennessee and the US Supreme Court made key rulings.

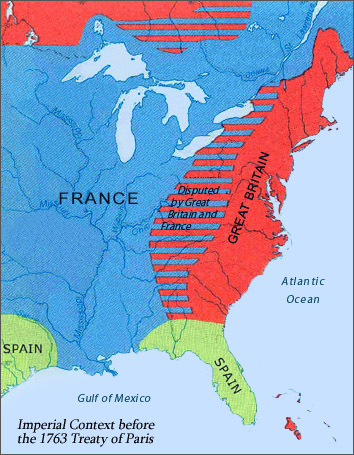

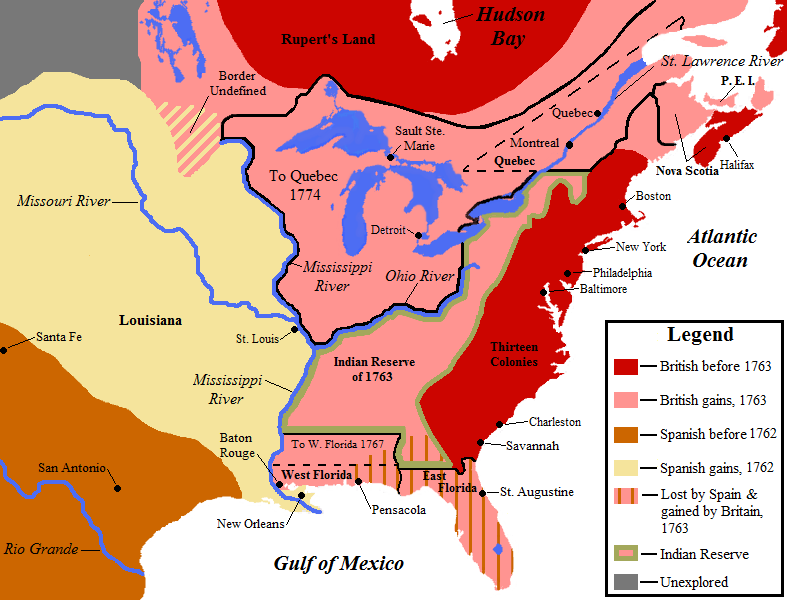

A major stimulus for clarifying the colonial boundaries beyond the Blue Ridge was the British victory in the Seven Years War, also known as the French and Indian War. That international conflict lasted from 1754-1763. Peace was followed by the Proclamation of 1763, announcing the decision of the British government to ban settlement in the watersheds of the Ohio and Tennessee rivers west of the Eastern Continental Divide.

The Treaty of Paris ending the war in 1763 increased security on the borderlands west of the Appalachian mountains. Military success removed the French from those regions, ending their ability to supply weapons and help Native Americans fight the English. However, expelling the French had been expensive. Maintaining British troops in the American colonies after 1763 to defend settlements in the borderlands from Native American attacks would increase the cost of victory.

Virginia land speculators, including the Ohio Company and Loyal Land Company, were major beneficiaries of the British investment in defeating the French. Great Britain had borrowed substantial amounts of money to pay for the French and Indian War. In London, officials expected the wealthy colonists with a "land hunger" for speculation to be willing to help repay the costs.

The two obvious ways to repay the debt were to 1) increase revenue from the colonies and 2) minimize the cost of maintaining military forces in North America after defeat of the French.

Proposals to increase revenue including imposing new taxes on the North American colonists. The 13 colonies had benefited immensely from the decisions in London to send warships and troops from Britain to seize the Ohio River Valley and Canada. From the perspective of London officials, it was only fair that the colonies should help repay at least a portion of that debt.

The colonists did not view the situation the same way as officials in London. Leaders in Virginia and other colonies failed to acknowledge the benefits of raising colonial taxes to repay the costs of providing the imperial "redcoats" who had provided better border security.

Colonial leaders were more than just ungrateful, selfish beneficiaries of English military power. Most officials in the colonies were Americanized by the 1760's, with a focus on how the colonies would benefit from the imperial system rather than just send revenue to London. Assisting an island across the Atlantic Ocean to extract wealth from its colonies, so London officials received the benefits from the investment risks taken by colonial venture capitalists, was not seen as "fair" on the American side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Colonial leaders objected quickly to new imperial taxes in part because the Americans were looking forward with an eye on future rewards from developing the acquired territory. Sending taxes to London reduced investment capital in the colonies and constrained the elites in each colony from getting even richer.

Though the initial tax burden was low, American leaders were alarmed by the precedent of Parliament imposing direct taxes (as opposed to indirect taxes, such as duties on shipping). Individual American colonies paid for lobbyists to represent their separate interests in London, but had no elected representatives in Parliament. That meant there was no effective way to limit future increases in imperial taxes through the political process. The precedent of repaying Britain for the costs of the French and Indian War could lead to ever-increasing taxes on Americans, taxes that could squeeze the colonists to fund the costs of maintaining/expanding an empire in Ireland, India, and elsewhere.

To accommodate American objections, London officials proposed a variety of different taxes in the 1760's. Colonists resisted them all. That resistance led to the Stamp Act crisis in 1765, the Boston Tea Party in 1771, and ultimately the American Revolution in 1775.

Efforts to reduce costs of government were equally controversial. The Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III, established a new settlement boundary that required colonists to stay on the eastern side of the proclamation line. The Indian Reserve on the western side was placed off-limits.

The Proclamation of 1763 blocked colonists from continuing the western migration which began soon after Jamestown had been established. The pattern of colonists settling on lands claimed by Native Americans, then demanding help from colonial governments to respond to the inevitable attacks, would be broken. The Proclamation of 1763 particularly upset members of the Virginia gentry who were influential enough to get a land grant, and had anticipated getting wealthy by selling western lands to new settlers.

The Proclamation of 1763 was intended to reduce the costs of maintaining British military forces on the western borderland of the colonies by minimizing settler-Native American conflicts. When settlers encroached onto lands claimed by Native American tribes, they fought back through raids and military action often called "massacres" by the colonists.

Despite the loss of French support, Shawnee and Cherokee warriors continued to resist trespass onto their hunting grounds in the watersheds of the Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee rivers. Raiders burned cabins and killed families on the western edge of the Carolinas, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York. Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763 made clear that colonial claims to the Ohio Country, based on charters issued in England and land warrants issued in Williamsburg, were not accepted by the current residents.

Colonists organized their own incursions that killed Native Americans, cut down cornfields, destroyed villages, and spurred yet another round of retaliation. There was no political or judicial process to resolve the conflicts, and outfitting the militia or sending imperial troops into the backcountry was expensive.

the defeat of the French and the 1763 Treaty of Paris triggered a need to define the Virginia-North Carolina boundary west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Library of Congress, Map Showing Imperial Context in North America before the 1763 Treaty of Paris

The obvious solution, at least as officials in London viewed the situation, was to separate the two sides.

Britain expected the Proclamation of 1763 to lead to treaties with the Native Americans that defined boundary lines, limited new colonial settlement to lands that had been ceded by the Native Americans to the colonies, and minimized warfare. Reducing Native American-settler conflicts by separating the two groups would limit the number of troops required to protect colonists from Native American raids, and would reduce the costs of negotiating peace treaties on the western edge of English settlement in North America.

In the Proclamation of 1763, British officials created an Indian Reserve for the newly-acquired lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The declaration blocked the representative assemblies and governors in the colonies from issuing land grants in the portion of western North Carolina and Virginia within the Tennessee River and Ohio River watersheds. The Proclamation Line created a "colonial growth boundary," one that would block settlement of territory of great interest to land speculators with friends and family sitting in the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg.

the Proclamation of 1763 was intended to establish an Indian Reserve to keep settlers and Native Americans apart, reducing the costs for military protection

Source: Wikipedia, Proclamation of 1763

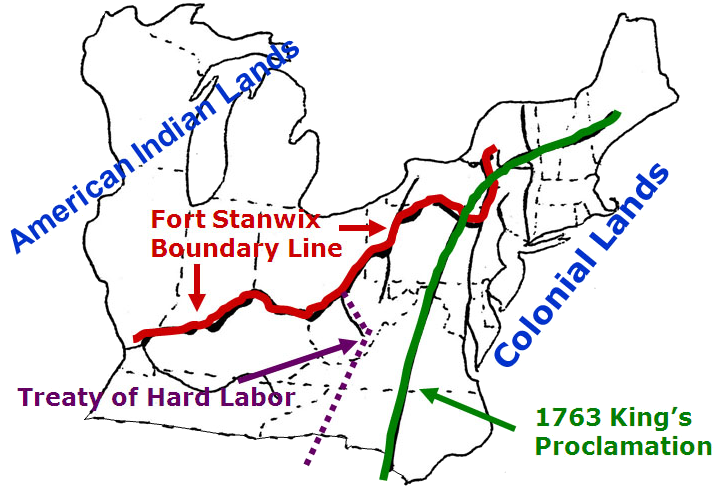

The next step after issuing the proclamation was for British officials to negotiate with different tribes. Treaties would define what lands would still be controlled by Native American groups, what territory would be ceded to Britain, and how the boundaries would be marked.

In 1768, British and colonial officials arranged for a peace treaty between the Iroquois and the Cherokee. The goal of that treaty was to stop the traditional long-distance raids by those two nations by bands which walked along the Blue Ridge, passing through territory which the British planned to acquire from each Native American nation. Peace between the Iroquois and the Cherokee would minimize raids that could involve settlers on the western edges of the colonies.

To acquire Native American rights to lands in the New River watershed, British officials negotiated the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor with the Cherokee. The Cherokee agreed to relinquish their rights to territory south of the Ohio River and east of the Kanawha River, including about half of modern West Virginia. The Cherokee hunted in that region, but few lived there. The Shawnee had a stronger claim to owning the land that was sold by the Cherokee.

Also in 1768, the Iroquois signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. They too abandoned whatever claims they had to the territory south of the Ohio River, all the way downstream to the mouth of the Tennessee River. The Iroquois had no settlements in that region and thin justification for asserting control over Shawnee lands, but the British ignored that factor. The British also used the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix to clear Iroquois title to lands in western New York, as well as south of the Ohio River.

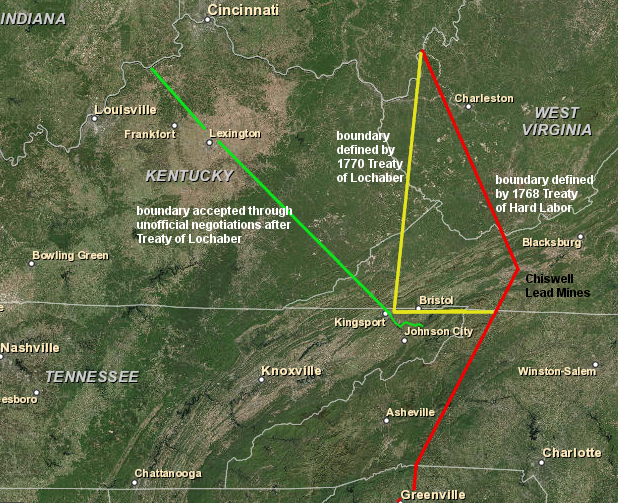

The Cherokee recognized that the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor would not define a final boundary; settlers were already living west of that treaty's boundary line. Two years later, the Cherokee ceded more land in the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. That moved the boundary even further west, authorizing occupation of additional territory in the New River and Holston River valleys north of the Virginia-Carolina border.

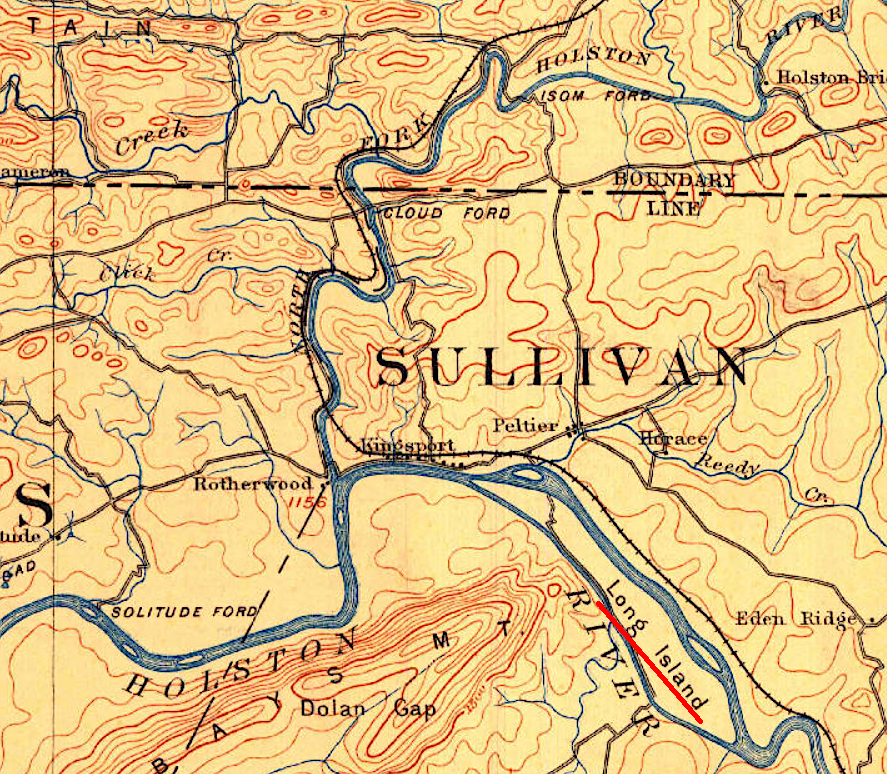

The Cherokee would not agree to surrender their settlement on Long Island in the Holston River, but in the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber they moved the boundary line westward from the line drawn in the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor to a point just six miles away from Long Island.

extending the 1749 survey of the southern boundary of Virginia was triggered by increased settlement in the borderlands and treaties with the Cherokee/Iroquois to clear title to lands in the Holston River valley

Source: National Park Service, 1768 Boundary Line Treaty Map

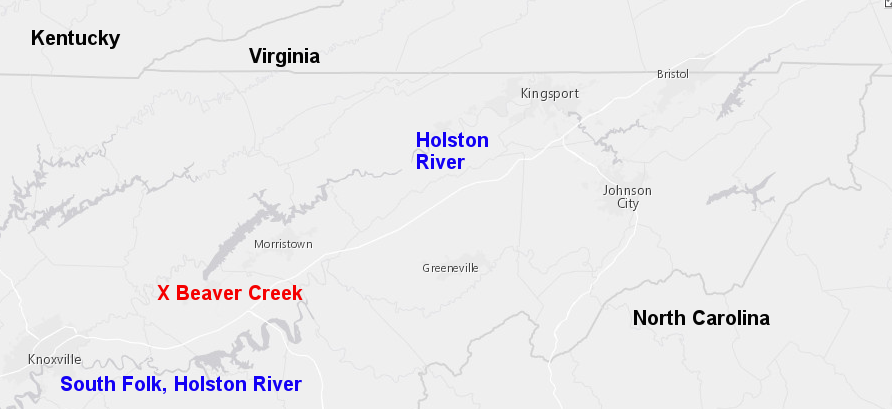

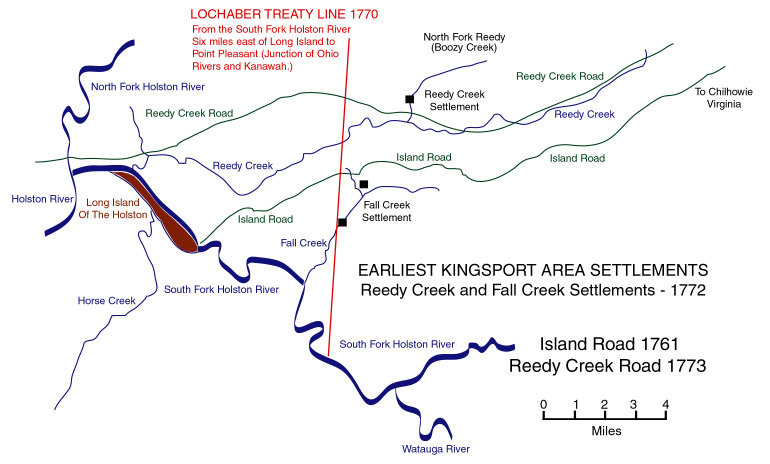

Anthony Bledsoe did an initial survey in 1771 that was not authorized by the Virginia General Assembly. It revealed the Virginia-North Carolina boundary was north of the settlements on the South Fork of the Holston River, but that information did not change the local custom of treating the Upper Holston River settlements as part of Virginia.

Later in 1771, John Donelson completed a separate survey. Donelson's survey was intended to mark the new boundary between British and Cherokee lands based on the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber.

Anthony Bledsoe surveyed to Beaver Creek in 1771, identifying that settlements in the Holston River valley were south of the Virginia-North Carolina boundary

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Donelson's Line did not follow the terms negotiated with the Cherokee. Most significantly, he ignored the provision in both the 1768 and 1770 treaties that defined the mouth of the Kanawha River as the northern end of the ceded lands. Instead, he surveyed a line northwest to the confluence of the Kentucky and Ohio rivers, substantially expanding the acreage which settlers could occupy. The Cherokee who accompanied him on the survey proposed the adjustment, perhaps hoping to steer new colonial settlement north into territory traditionally used more by the Shawnee.

Donelson's Line (green, above) surveyed after modifying the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber gave Virginia control over land south of the 36° 30' parallel of latitude

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Donelson altered the southern boundary as well, knowing that the Virginia-Carolina border at 36° 30' parallel of latitude was located north of many farms already established by early settlers. The Cherokee agreed to move the Treaty of Lochaber line south to follow the South Fork of the Holston River to a point located six miles east of Long Island. Long Island is currently near Kingsport, Tennessee, and nearly five miles south of the modern Virginia-Tennessee border.

after the Cherokee agreed to modify the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, John Donelson surveyed a southern boundary defining Long Island as the southern boundary

Source: US Geological Survey, 1:125,000 scale Estillville, KY topographic quadrangle (1894)

That southern adjustment authorized the existing colonial settlement at Sapling Grove.

a historical marker at the train station in Bristol, Virginia commemorates Evan Shelby settling at Sapling Grove.

The Cherokee also agreed to allow settlements further south of the southern edge of the Donelson Line. They signed the 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals with Richard Henderson, and negotiated a deal with those already living on the Watauga River.2

John Donelson's 1771 survey altered terms of the Treaty of Lochaber to legitimize existing settlements south of the Virginia-Carolina border and north of the South Hoston River

Source: Discover Kingsport, Maps: Kingsport

The need for boundary surveys was driven by the need to define legal boundaries for colonists who sought to increase their wealth by acquiring land. Processing the legal transactions required going to a county courthouse to get and maintain clear title.

The alternative to creating a local government was to force settlers to travel a long distance to file the documents required to establish land ownership. Rather than make such difficult and time-consuming trips, some settlers in the borderlands chose to live "in a state of nature" without clear legal rights to the land they occupied.

The Virginia General Assembly in Williamsburg created new counties along the North Carolina border as population increased on the western edge of the colony. Residents in a new county benefitted from having to travel a shorter distance to a courthouse, but also had to pay the taxes required to fund local militia/civil officials and the construction of a new courthouse. Typically, the more-wealthy settlers agreed among themselves that the benefits would be worth the extra taxes and then petitioned the colonial legislature to charter a new county.

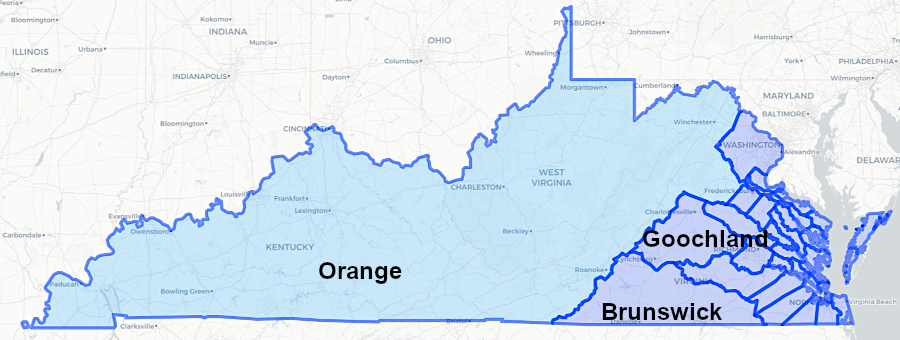

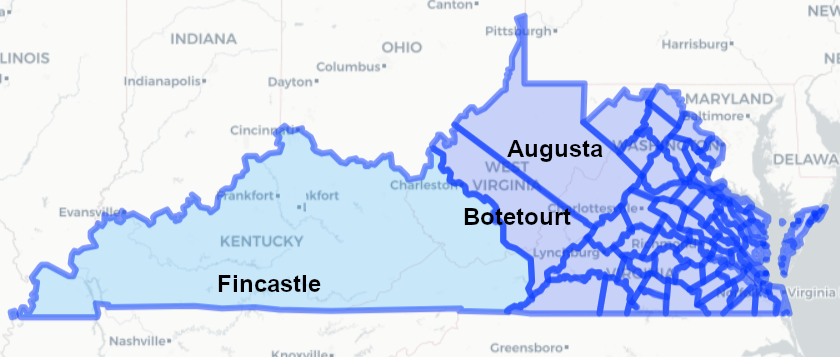

The Virginia General Assembly established Orange County at the start of 1735 (new calendar), extending local government for the first time west of the Blue Ridge. The boundaries of Orange County included all territory claimed by Virginia that was west of the Blue Ridge and south of the Ohio River, extending west to the "utmost limits of Virginia." The southern boundary was the 36° 30' parallel of latitude, the southern edge of Virginia as defined after the creation of the Carolina colony.

Orange County was divided and Augusta County formed in 1738. When Virginia and North Carolina commissioners surveyed the southern boundary in 1749, they blazed trees that marked the southern edge of an already-existing Augusta County in Virginia. In contrast, in 1749 North Carolina had organized counties only to the western end of the 1728 "dividing line" survey.2

the General Assembly created Orange County in 1735 with a southern boundary at the 36° 30' parallel of latitude, extending westward to the 1612 charter limits

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

in 1749, North Carolina had organized counties only to the western end of the 1728 "dividing line" survey

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The colonial population on the southwestern edge of Virginia increased after the French and Indian War ended in 1763. In response, the Virginia General Assembly divided Augusta County in 1770 and formed Botetourt County from its southern half. In 1772, the General Assembly created Fincastle County out of Botetourt County.

Fincastle County was created in 1772

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

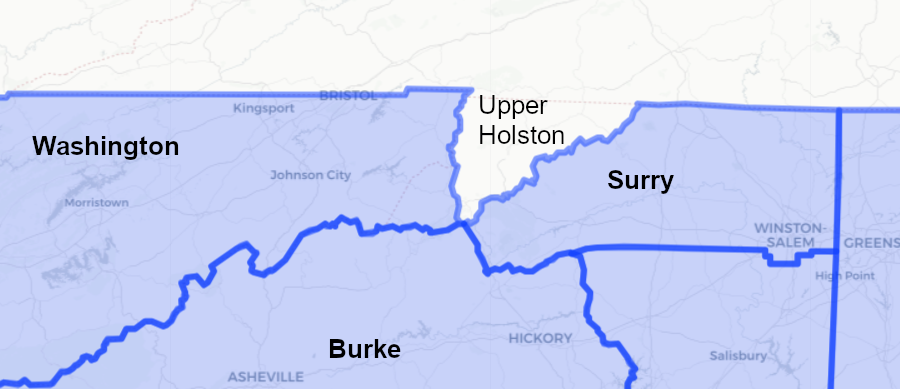

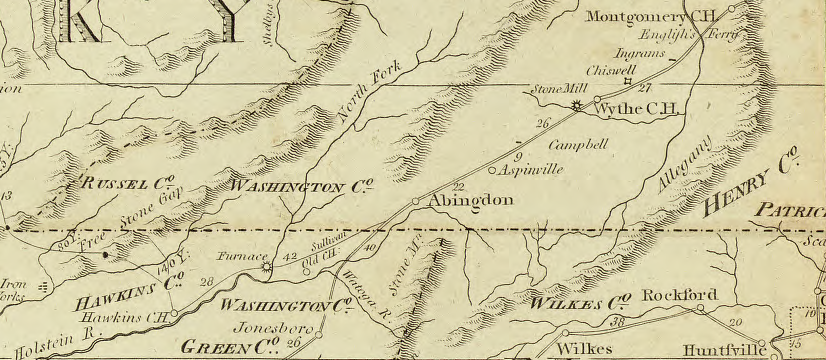

In 1776, the General Assembly divided Fincastle County into Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky counties.

the General Assembly created Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky counties in 1776

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

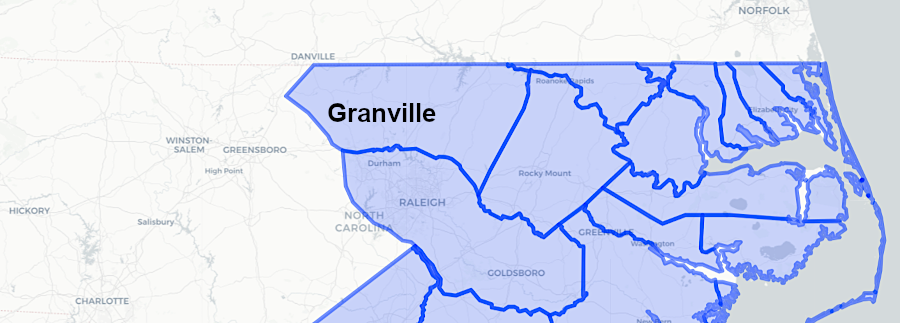

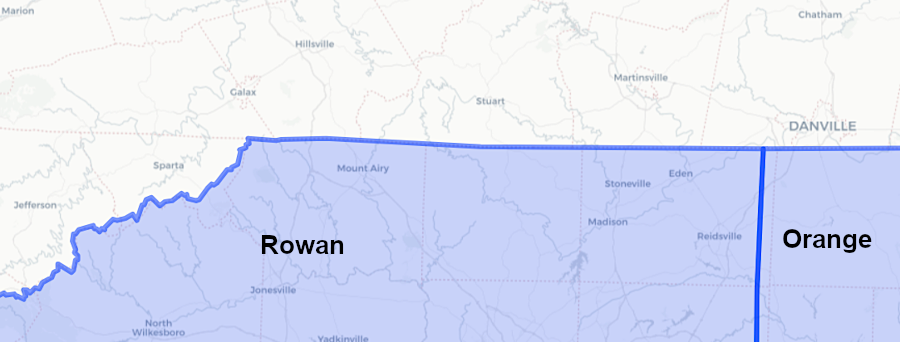

Colonists were slower to move into western North Carolina, but that state followed a similar pattern in creating new counties as population grew. In 1753, North Carolina created the first counties west of the spot where the North Carolina commissioners had stopped surveying in 1749. The western edge of Rowan County extended to the base of the Blue Ridge, where Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry had quit finally in 1749.

North Carolina established Rowan County in 1753, extending its defined border with Virginia to the base of the Blue Ridge

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Rowan County was divided in 1771; the northern part next to the Virginia border was named Surry County.

Squatters in the new counties may not have worried about legal land titles, but knowing the location of the Virginia-Carolina border was essential for settlers planning to purchase land on the area during the 1770's. Land surveys had to be completed by authorized county surveyors and filed in the appropriate county courthouse to establish legal ownership.

Settlers planning to purchase the land they were improving needed to know whether Virginia or North Carolina land warrants were valid, and where to file their surveys. Protecting land ownership against rival claimants required knowing whether Virginia or North Carolina courts would resolve boundary disputes. Colonial and later state officials were also interested in a clear Virginia-North Carolina boundary, in order to receive the appropriate tax revenue and to organize militia if needed for military action.

Efforts to establish the Virginia-North Carolina boundary were renewed during the American Revolution, despite the disruption of British invasions of Virginia via the Chesapeake Bay. The hunger for land by settlers in the upper Tennessee River watersheds led to conflict with Native American tribes, especially Cherokee and Shawnee who sided with the British. The best guarantee that the settlers would choose to fight for independence was to assure them that the new state governments would confirm their land claims. Confusion over land rights in the backcountry of southwestern Virginia created the risk that settlers would find a way to "cut a deal" with the British.

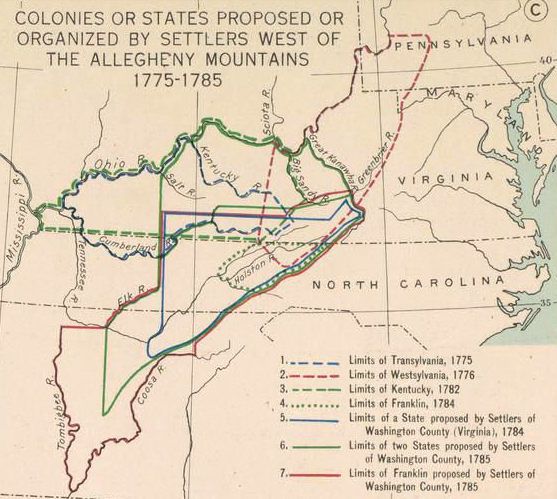

The 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals created an alternative to getting legal title from the Virginia government. Richard Henderson and other land speculators tried to bypass the colonial governments east of the Blue Ridge and create their own government of Transylvania.

Henderson's Transylvania Company purchased whatever rights the Cherokees had to 20 million acres of land between the Kentucky and Cumberland rivers, west of the line surveyed by John Donelson after the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. The Transylvania Company also purchased a Path Deed to provide access to the territory west of the Cumberland Mountains.

The Watauga Association negotiated its own deal with the Cherokee, who allowed settlers to occupy lands south of the Donelson Line. However, any deed from Virginia to parcels south of the latitude of 36° 30' - and particularly south of the Donelson Line, east of Long Island - had questionable legitimacy.

The new state governments had to ensure there was a process for acquiring clear title to land if the far western settlers were expected to fight for the American side in the Revolutionary War. State officials recognized that they had to define the location of the Virginia-North Carolina border, and to organize county governments which could confirm land titles.

between 1775-1785, settlers in western Virginia and North Carolina proposed multiple solutions to creating local governments not dominated by Tidewater planters

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Colonies or States Proposed or Organized by Settlers West of the Allegheny Mountains, 1775-1785 (Plate 41c, digitized by University of Richmond)

The confusion over the boundary led to questions regarding the legitimacy of the results of the Washington County 1776 election for delegates to the Virginia House of Delegates. The losers (Arthur Campbell and William Edmiston) claimed the winners (Anthony Bledsoe and William Cocke) had been elected with the help of voters who lived in North Carolina rather than in Virginia.

The Virginia General Assembly rejected the argument and allowed Anthony Bledsoe and William Cocke to serve. In the 1777 election, Anthony Bledsoe was re-elected and Arthur Campbell joined him as a delegate.

William Cocke had been a winning in the 1776 election, but not in 1777. Once he was no longer a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, Cocke claimed he lived in North Carolina. He refused to pay Virginia taxes, saying anyone who did so was a fool.

In the Virginia General Assembly, Bledsoe led the effort to have the Fry-Jefferson survey extended west from Steep Rock Creek. An official survey was needed to define the Virginia-North Carolina boundary through the Holston River valley.3

In 1777, after North Carolina had declaring independence and no longer had to even pretend to recognize the Proclamation of 1763, the state legislature created Washington County and placed its western border on the Mississippi River. However, the Upper Holston River territory, where colonists operated as if they were in Virginia based on the Donelson Line, was not included within Washington County. That decision created a notch in the Virginia-North Carolina line.

when North Carolina established Washington County in 1777, it omitted the Upper Holston River where settlers operated as if they were in Virginia

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

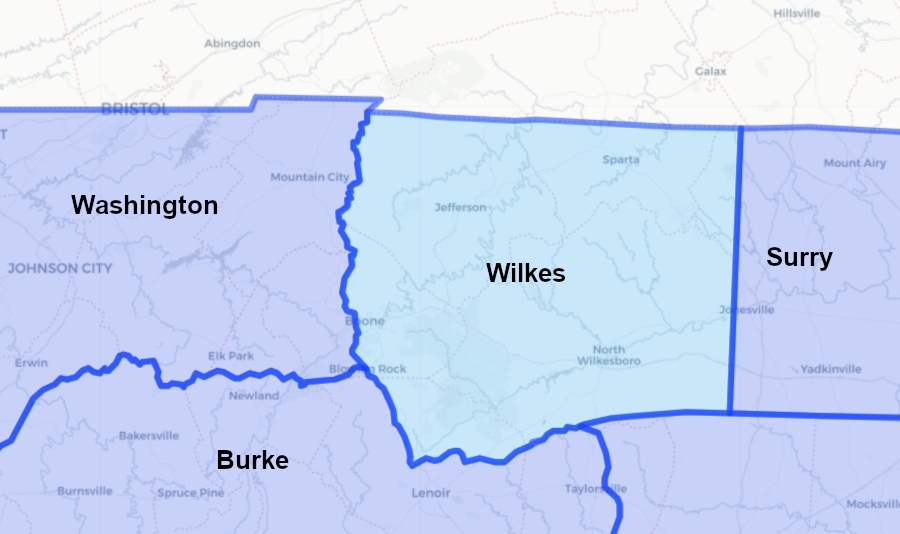

The North Carolina legislature closed that gap in 1778 when it created Wilkes County.

North Carolina claimed the Upper Holston valley when it created Wilkes County in 1778

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

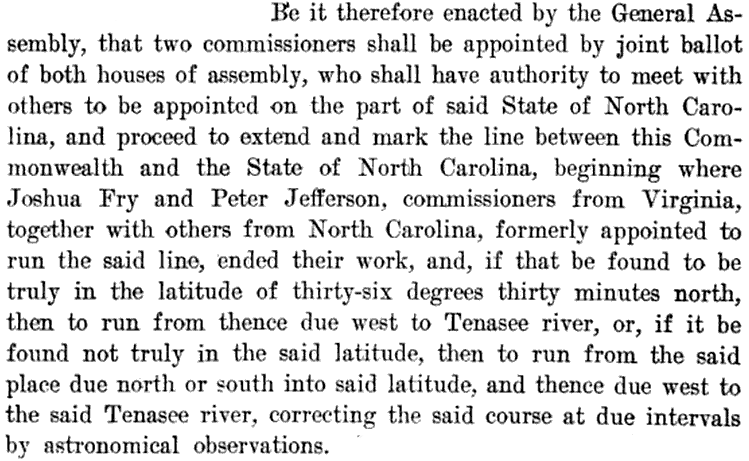

Virginia authorized a boundary survey in 1778 and North Carolina concurred in 1779, thirty years after Fry and Jefferson had stopped at Steep Rock Creek. During the middle of the American Revolution, Virginia and North Carolina committed resources to a boundary survey far to the west of where the British were a direct threat. That investment in scarce resources in wartime reflected the demand for legally-defensible land titles in the Holston River valley.

Virginia authorized a survey of its North Carolina boundary in 1778

Source: Lewis Preston Summers, History of Southwest Virginia, 1746-1786, Washington County, 1777-1870 (p.696)

In 1779 both Virginia and North Carolina still claimed lands westward to the middle of the Mississippi River, based on their ancient colonial charters and the 1763 Treaty of Paris. Neither state had relinquished its western land claims to the Continental Congress. The states of Tennessee and Kentucky would not be created for another decade or two.

Virginia and North Carolina appointed surveyors and commissioners to mark their joint boundary once again. Virginia was represented by Dr. Thomas Walker and General Daniel Smith, while Colonel Richard Henderson, William Bailey Smith, and John Williams represented North Carolina.

the 1755 John Mitchell map showed Thomas Walker's cabin, built on the Cumberland River in 1750 as he explored beyond the Cumberland Gap for the Loyal Land Company - and the end point of the 1749 survey "336 miles from the sea"

Source: Library of Congress, John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions

in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

Both survey teams had representatives with strong personal agendas. Walker was active in the Loyal Land Company, with its grant from Virginia for 800,000 acres in southwestern Virginia. The further south the line was drawn, the more land would be available for the Loyal Land Company to select. Henderson was the prime mover behind the Transylvania effort, through which he had hoped to acquire title to 20 million acres in the Kentucky region. He recognized the strong opposition of Virginia officials to Transylvania. It was in his interest to extend the line to the north and hope he might have better luck getting approval from North Carolina.

the 36° 30' boundary established in the 1665 charter was supposed to be extended westward by the 1779-80 survey

Source: Library of Congress, Partie occidentale de la Virginie, Pensylvanie, Maryland, et Caroline (1781)

The 1779 survey was supposed to start at Steep Rock Creek. The commissioners and surveyors could not find the point where Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry stopped in 1749, though they searched for two weeks. The marks made on trees to define the Virginia-North Carolina boundary line in 1749 had disappeared over the last 30 years.

Dr. Walker recorded:4

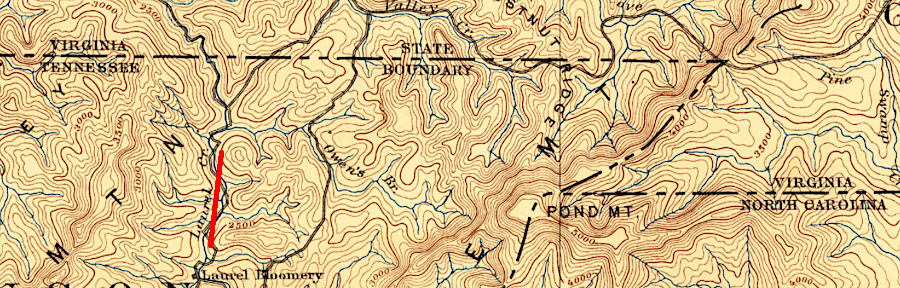

The two survey teams agreed to begin the new survey by defining the latitude of 36° 30' and choosing a new point of beginning. The surveyors assembled at a location, most likely near Whitetop Mountain, that had a clearing where the sun and stars could be observed. The North Carolina and Virginia commissioners agreed upon the latitude and longitude of that spot. Though no marks of the 1749 survey could be found at Steep Rock Creek, the 1779 commissioners determined they needed to move slightly more than one mile south from where they had assembled to reach the latitude where the 1749 survey had stopped.

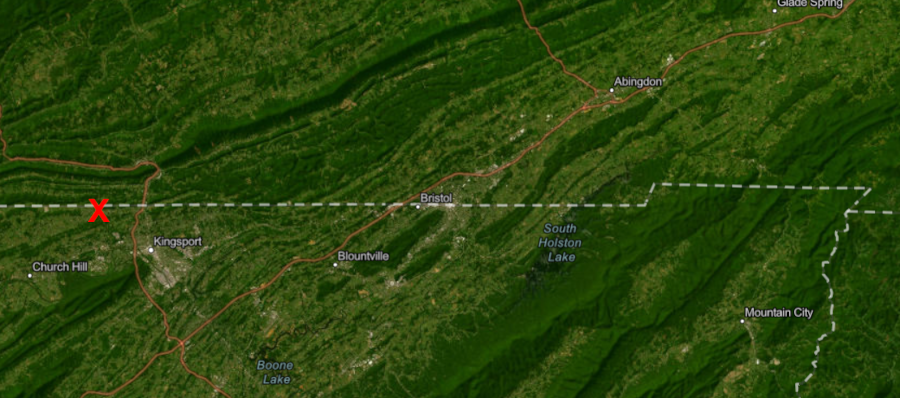

From the point of beginning, the team of Carolina and Virginia surveyors moved west into the upper Holston River valley. After 45 miles of moving west, the surveyors reached Carter Valley west of modern-day Kingsport, Tennessee. There, the North Carolinians concluded that the line being surveyed was two miles too far south of the 36° 30' line. If continued, the boundary would place both Cumberland Gap and the French Lick settlement on the Cumberland River in Virginia. (French Lick, now the city of Nashville, ended up being about 30 miles south of the Walker Line.)

One of the Virginia commissioners, General Daniel Smith, was willing to consider the possibility that iron ore in the mountains had deflected the needle in the surveyor's compasses. The two North Carolina commissioners and on from Virginia moved north to start a new survey line.5

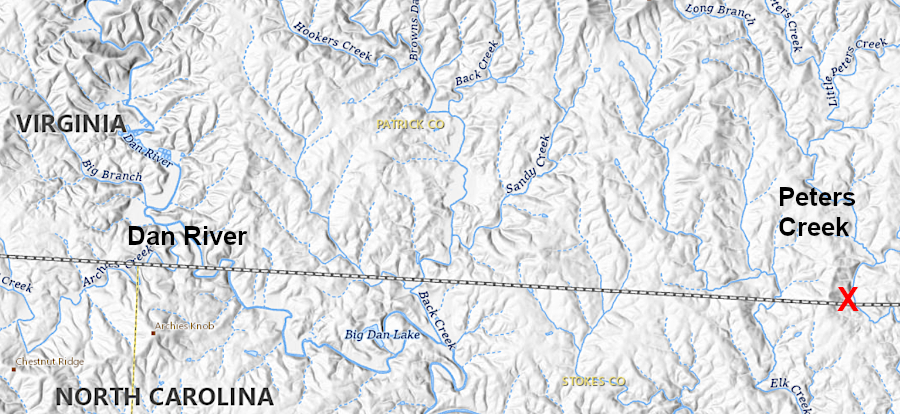

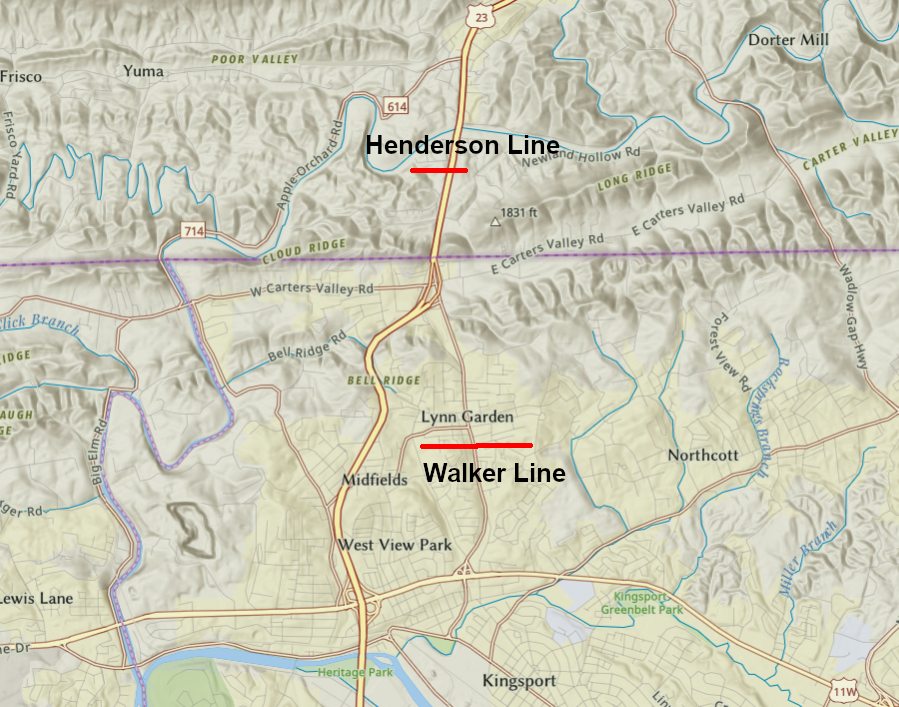

at Carters Valley (red X), the North Carolina surveyors insisted on moving the line two miles north

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

They surveyed back towards Steep Rock Creek. Smith concluded halfway back to the starting point that he had made a mistake, and that the original line was correct. He rejoined Walker, after writing in his diary:6

The North Carolina surveyors reached their starting point, then returned to Carter Valley. The two teams then surveyed westward in separate efforts, defining lines about two miles apart.

The Virginia commissioners established what became known as the "Walker Line." The North Carolina commissioners marked a separate "Henderson Line." Both started at Steep Rock Creek, since the North Carolina commissioners had stopped at Carter Valley and run a line eastward back to the original starting point.

The North Carolina commissioners went west from Carter Valley to Cumberland Mountain. They created the Henderson Line as they paralleled the Virginia commissioners surveying their Walker Line. The Henderson Line remained abut two miles north of the Walker Line. After the North Carolina commissioners reached Cumberland Mountain, they stopped surveying and went home.

The result of the disagreement was two proposed boundaries. Surveys of tracts were tied to the defined but separate Henderson and Walker lines, but those lines were separated by a gap ("gore") for over 100 miles between Steep Rock Creek and Cumberland Gap. If the state legislatures chose to accept the Henderson Line, more land would be included within North Carolina and the size of Virginia would be reduced. If the two state legislatures accepted the Walker Line, the reverse would be true.

In the territory where state control was not clear, surveys of tracts could define the boundary of land ownership - but the legitimacy of those claims remained unclear. Neither state could collect taxes effectively, force residents to join the militia, or ensure legal title to tracts of land.7

tracts with original survey corners tied to the Henderson and Walker lines show the competing survey lines were over two miles apart

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As in 1728, in 1779 the Virginians were more optimistic about the demand for western settlement. Walker and Smith continued the boundary survey westward after the North Carolina commissioners quit.

The Virginia surveying west beyond Cumberland Mountain to Deer Fork, 124 miles west of their starting point at Steep Rock Creek. At that spot, where the terrain was steep and rocky, there was little river cane for the horses to graze upon late in the Fall.

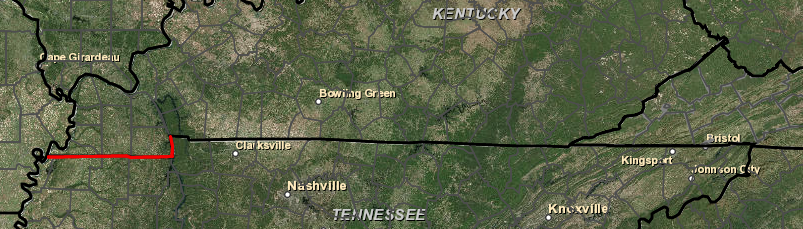

Walker and Smith chose to skip westward 109 miles and start surveying again at the Cumberland River. Defining the boundary in the mountains could be postponed, but more settlers were expected to move into the better farmlands in the river valley. A boundary survey there would clarify more land titles. The community of French Lick (now Nashville) was already growing on the Cumberland River in what was presumed to be Washington County, North Carolina.

At a new point of beginning on the Cumberland River, the Virginia survey team determined the latitude of 36 degrees 30 minutes through astronomical observations. They marked the boundary by blazing trees for 41 more miles west to the Tennessee River. At that river, they ended up being over 17 miles north of the desired 36° 30' - and, more importantly, north of French Lick. The error benefited North Carolina and, later, Tennessee.8

The decision by Virginia and North Carolina to complete a boundary survey and clarify land ownership rights was helpful in generating support for American independence west of the Blue Ridge, even though there was a two mile wide gap between the Henderson and Walker surveys.

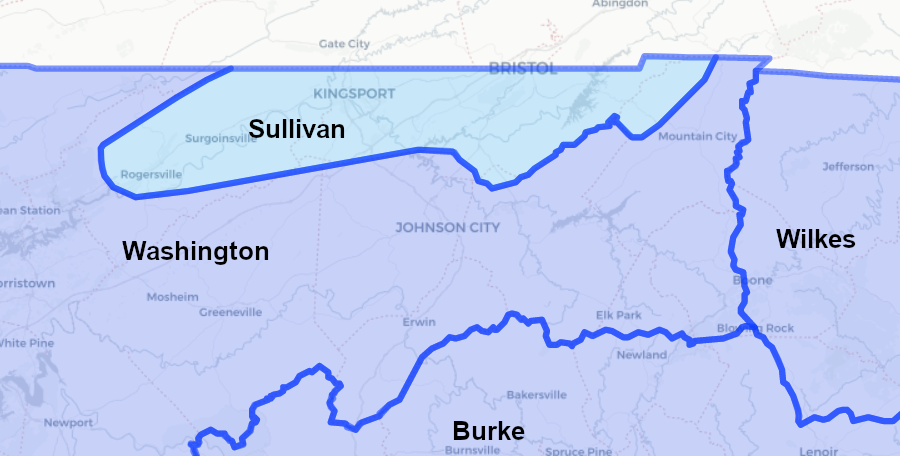

North Carolina created Sullivan County in 1779, after completion of competing boundary surveys reaching westward to Cumberland Mountain

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1780 settlers living in the upper Tennessee River watershed assembled in Abingdon and Sycamore Shoals, then marched southeast to fight the British forces and Loyalists that were led by Lord Cornwallis. The "Overmountain Men" marched across the Blue Ridge to defeat a group of Loyalists, led by Major Patrick Ferguson, in a decisive engagement at the Battle of King's Mountain.

In 1784, after the American Revolution ended, North Carolina made an initial cession of its western lands to the Congress. The initial cession was rescinded and several North Carolina counties west of the Blue Ridge petitioned the new Congress to admit them as the State of Franklin. Congress rejected the proposed 14th state. Ultimately Virginia and North Carolina each gave Richard Henderson 200,000 acres to eliminate his land claims and "quiet the title" to land grants.

In 1790, North Carolina finally relinquished its western land claims to the new Federal government and the US Congress created the Southwest Territory. Much of southwestern Virginia became the State of Kentucky in 1792, and the Virginia-Southwest Territory border stretching west of Cumberland Gap became the Kentucky-Southwest Territory border.

North Carolina agreed to the Walker Line as the state boundary on December 11, 1790 before ceding its western lands to the Federal government. Leading up to that decision, a committee in the North Carolina legislature reported in 1789:9

The Virginia General Assembly concurred with the North Carolina decision and declared the Walker Line to be the state's southern boundary in an act passed on December 7, 1791. However, the US Congress had accepted North Carolina's cession of its western lands on April 7, 1790.

Governor Blount, appointed by President Washington to manage the Southwest Territory, refused to accept the cession as valid. He noted that the new boundary had not been formalized by both states before establishment of Federal control, and the US Congress had not consented to the alteration of the state boundaries. Because no taxes were levied by the Federal government, a substantial percentage of settlers in the gap between the Walker and Henderson lines saw an opportunity to avoid paying Virginia taxes by claiming they lived in the Southwest Territory and were not residents of Virginia.10

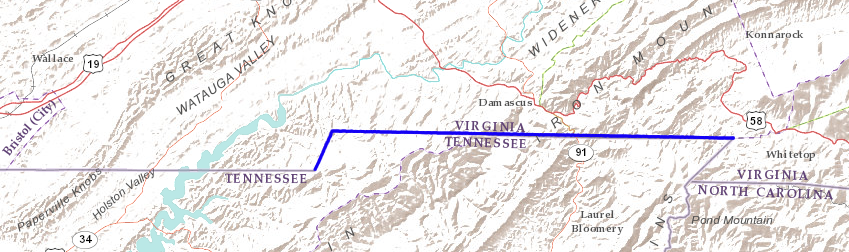

Virginia was bordered by the Southwestern Territory between 1790-96, after North Carolina ceded its western lands to the national government and before the State of Tennessee was accepted into the Union

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the state of Kentucky: with the adjoining territories, 1795

Congress converted the Southwest Territory into the new state of Tennessee in 1796. The zig-zag boundary between the 1749 survey's end point and the 1779 survey's point of beginning, the Virginia-North Carolina boundary between 1779- 1790 and the Virginia-Southwest Territory boundary between 1790-1796, became today's Virginia-Tennessee boundary.

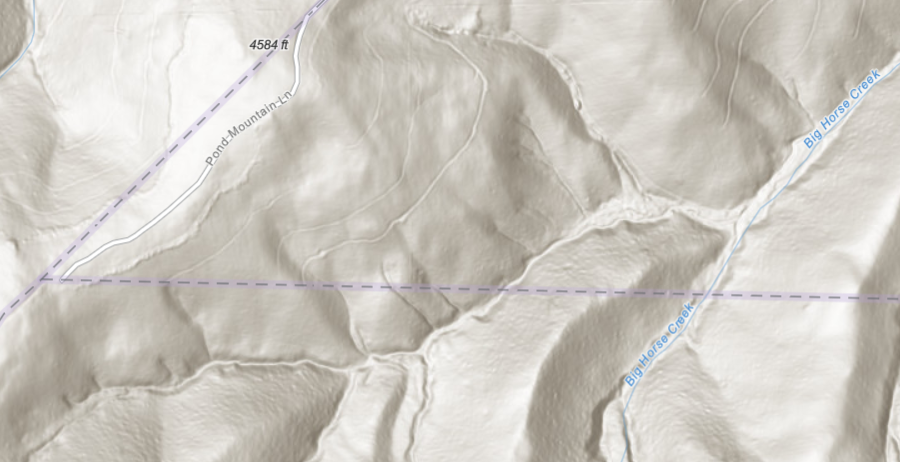

the current Tennessee-Virginia boundary is out of alignment with the North Carolina-Virginia corner because the 1779 Walker Line survey started northeast of Steep Rock Creek, where Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson had stopped in 1749

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The debate about how to resolve the disputed Virginia-North Carolina boundary on its western end continued after creation of the independent states of Kentucky and Tennessee. According to the 1665 grant by King Charles II, the Virginia-Tennessee border and the Kentucky-Tennessee border should match the 36° 30' parallel of latitude.

The current border is obviously not straight, and does not match tha line of latitude defined in the revised 1665 charter from King Charles II establishing North Carolina's northern boundary. Sapling Grove, now the cities of Bristol VA and Bristol TN, ended up being six miles north at 36° 36' rather than at 36° 30' of latitude.

GoogleMaps shows the latitude of the TN-VA border in Bristol, at the middle of State Street next to the railroad station

Source: GoogleMaps

The actual border is a result of inadequate expertise and survey equipment in the 18th Century, a series of adjustment by commisioners and surveyors in the field, and political compromises. After multiple lawsuits, the Viginia-Tennessee boundary is no longer in dispute..

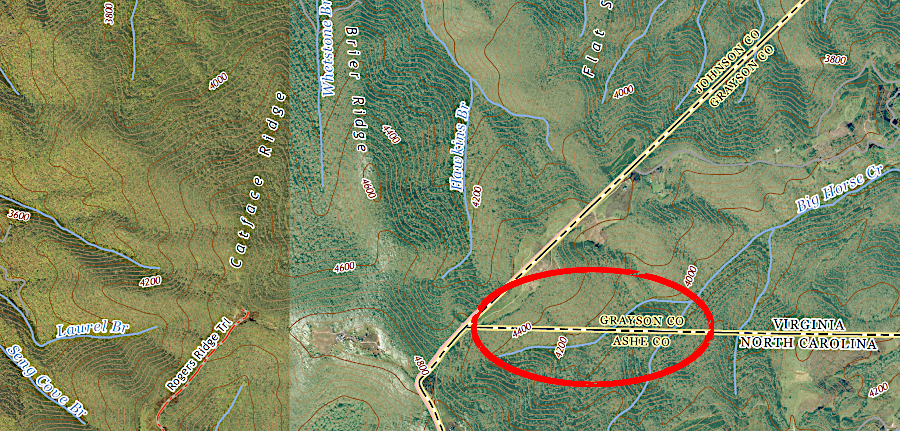

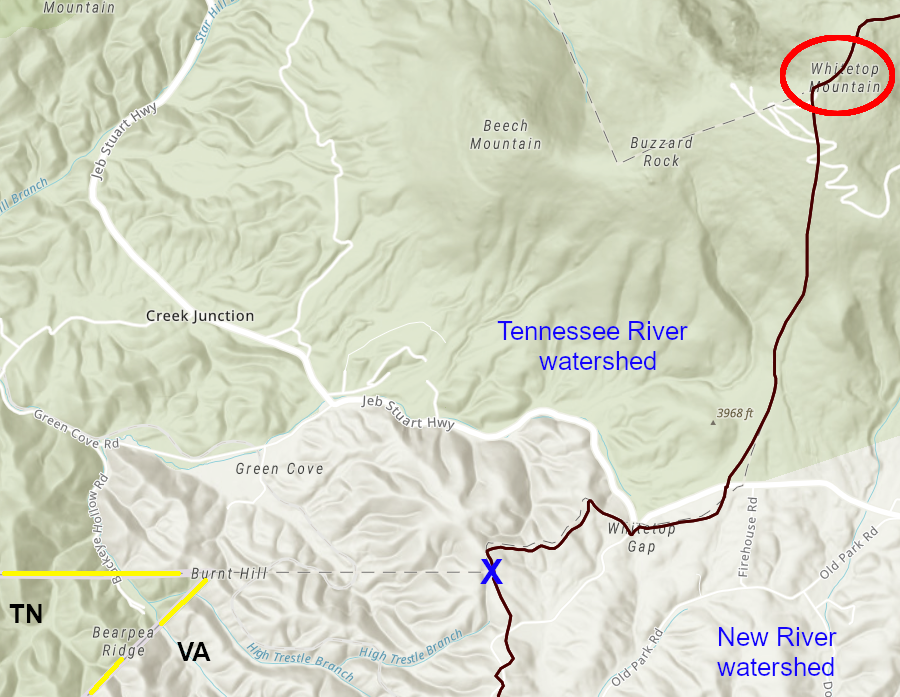

the western end of the 1749 Jefferson/Fry survey marks the modern Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia boundary (red circle)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

a simple stone marks the modern corner of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee

Source: Jimmy Emerson, DVM, "The NC-TN-VA Corner Marker," (top image and bottom image)

At its far western end on the Tennessee River, the Walker Line was almost 10 miles north of the intended latitude. In 1820, Kentucky accepted the Walker Line as its boundary, even though as a result of surveying errors Kentucky lost territory to Tennessee. As mitigation, Tennessee gave Kentucky title to all the remaining vacant (unpatented) land between 36° 30' and the Walker Line.

Kentucky and Tennessee also agreed to move their boundary south between the Tennessee-Mississippi rivers, after the Jackson Purchase extinguished the claim of the Chickasaws to that territory. The Walker Line, which had veered too far north, had stopped at the Tennessee River. West of that natural feature, Kentucky and Tennessee adopted the 36° 30' parallel as their boundary and it was surveyed in 1819 by Robert Alexander and Luke Munsell.11

the Kentucky-Tennessee border was adjusted west of the Tennessee River to mitigate for errors made by the 1779-80 Walker Line survey

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

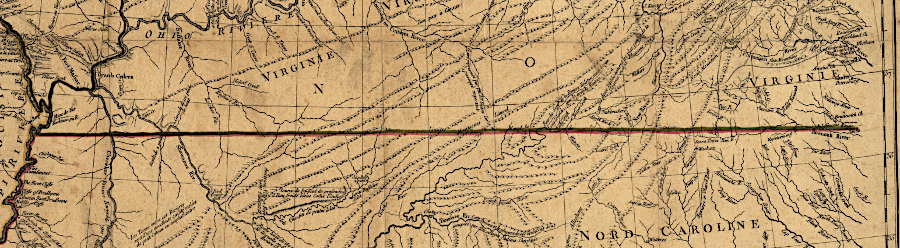

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson displayed the Virginia-Carolina border as a straight east-west line at 36° 30'

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina

Legally, land ownership boundaries are not defined by latitude, longitude, or negotiated compromises made in state capitals. Land ownership boundaries are defined by on-the-ground marks and monuments, physical indications such as blazes on trees or stones/metal bars placed into the earth by the surveyors. The ability of Global Positioning System (GPS) and Geographic Information System (GIS) technology to define the 36° 30' parallel accurately is irrelevant in modern land ownership disputes.

Pioneer surveyors literally dragged iron chains west from the Atlantic Ocean, cutting a path through the natural vegetation and documenting the bearings/distances between monuments. In legal disputes since then, the monuments set on the ground are almost always defined as the property boundaries, no matter what documents may have said were supposed to be the dividing lines between properties or colonies/states.

The southern boundary line of Virginia with Tennessee has a series of curves and notches; it is not just a series of straight lines. The reasons for the minor shifts in the Virginia-Tennessee border are not clear. There are tales about hard-drinking surveyors losing their sense of direction, and surveyors choosing to deviate from straight lines when the topography or vegetation was to difficult to cross. Strong-willed landowners may have convinced surveyors to avoid cutting through pre-existing parcel boundaries. In addition, iron deposits in the mountains affected the compasses used in the 1700's and 1800's.

One author concluded that many of the explanations for the adjustments were just made-up tales, and the most likely reason is that landowners requested boundary adjustments in order to keep their property in one state or the other. In his opinion, the large notch between North Carolina and Bristol, where the state line jumps north over 1.5 miles, was:12

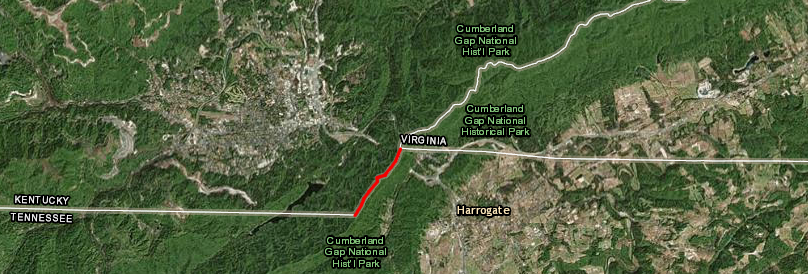

the Virginia-Tennessee-Kentucky border is marked at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

In 1796, most of the Southwest Territory was included within the boundaries of Tennessee and the new state was admitted to the Union. The 1796 Tennessee constitution defined the northern boundary as the 36° 30' parallel line. By that time Kentucky was also a separate state, so both Virginia and Kentucky had an interest in defining Tennessee's northern edge.

In 1802, Virginia and Tennessee agreed to survey a compromise boundary; each state would be given half the territory between the Henderson Line and the Walker Line. The Compromise Line of 1802 was surveyed from Whitetop Mountain to Cumberland Gap.

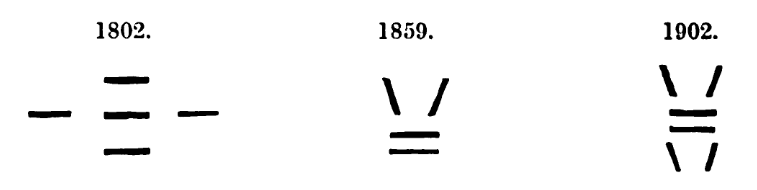

Commissioners for Virginia were Joseph Martin, Creed Taylor, and Peter Johnston. Commissioners for Tennessee were General John Sevier, Moses Fisk, and General Joseph Rutledge, and surveyors were Brice Martin and Nathan Markland. Martin and Markland marked blazes in a diamond pattern, so that 1802 survey is known as the "diamond line."

![]()

diamond blaze of 1802 survey

It would appear the 1779 commissioners/surveyors recognized that they did not start on the 36° 30' line. The 1802 commissioners/surveyors were equally opaque in their official reports regarding where the survey began at Whitetop Mountain.

It is possible that the 1779 commissioners/surveyors saw a relatively open stretch west of Whitetop Mountain that was north of the 36° 30' line. Rather than go a mile or two south and cut a difficult path through the forested mountains, the surveyors may have blazed a line that was more convenient than accurate for the first 15 miles.

The impact of that survey error would have been minimal. Land values of the area were very low at the time. The hilly terrain with thin soils was unsuitable for farming. The impact of iron in the mountain affected the declination of compasses, but there were no obvious mineral resources to exploit. Without a transportation network to ship timber to market the forests were not yet worth much money.

After 15 miles, the 1779 surveyors reached Denton Valley near the South Holston River. At that location, the value of the land increased enough to justify greater accuracy. That may explain why the boundary line drops south, getting closer to the 36° 30' line. It is possible that the Virginia commissioners in 1779 were willing to give North Carolina some low-value mountain acreage in order to simply the boundary survey, but decided that bottomland in the Holton River watershed was too valuable to sacrifice.

An 1859 attempt to retrace the survey found a blaze on the eastern edge of the 1802 survey, on a ridge known locally as the "Divide." That ridge was three miles southwest of the peak of Whitetop Mountain, and its location on the watershed divide between the New and Tennessee rivers explains the name.

No other marks of the 1802 survey were found further east of that mark on the "Divide." The blaze was no different from other surveying marks found to the west; there was no indication it identified a survey corner or point of beginning.

That far eastern mark, if it was actually found in 1859 on the Divide as indicated with the blue X below, was not used to identify what became the northeastern corner of Tennessee. The boundary line is not on the watershed divide separating the Tennessee and New rivers.

In 1902, surveyors retracing the 1802 line speculated that the 1802 surveyors found the western end of the 1779 line, then chose to go northeast to a point that was halfway to the summit of Whitetop Mountain. That halfway point would be halfway between the Henderson Line and Walker Line, so it would have been an appropriate point of beginning for marking the compromise boundary in 1802.

in 1859 surveyors found a mark of the 1779 boundary survey on the watershed divide (blue X) separating the New and Tennessee rivers - which is not the border between Tennessee and Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The 1859 survey found survey marks going 15 miles westward to Denton Valley. The boundary line then dropped south at a 22° angle for 1.6 miles before angling back to a due west direction. From that point, with a few exceptions, the 1859 retracing of the boundary followed a straight line to Cumberland Mountain.

The surveyors were tasked with placing a stone monument to mark the boundary every five miles where there was no timber. The five chops on trees that had been made in 1802 to form diamonds, marking that old survey boundary, were disappearing as the trees died. The stones, sticking 2.5 feet out of the ground, were marked with a "V" on the north side and a "T" on the south side.

The 1859 report described succinctly the failure to find the point of beginning of the 1779 or 1802 surveys, and how the line was retraced to the west:13

At Cumberland Gap, Virginia's southwestern tip, there is a jog in the three state boundaries. The Virginia/Tennessee boundary is based on the 1802 compromise between the Walker/Henderson lines. The Kentucky-Tennessee line is located further south, based on the Walker Line.

the Virginia/Tennessee and Virginia/Kentucky boundaries are not aligned at Cumberland Gap

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online)

On August 7, 1869, the United States Coast Survey came to Bristol to oserve the solar eclipse and get an accurate measurement of latitude and longitude. As a side task, the bservers were directed to connect their monument to the state boundary line. Since local esidents could not agree on that boundary, the Federal team had to b flxible in implemnting thir instructions.

The official United States Coast Survey report includes this comment regarding the 1802 survey line, which in theory was marked in the middle between the Henderson and Walker lines:14

Virginia tried to re-open the question of its boundary with Tennessee in 1858, 1870, and then again in 1887. Virginia claimed that though its General Assembly had accepted the 1802 boundary, the line was not valid because the US Congress had not consented to the transfer of territory between the two states as required by the US Constitution.

Not surprisingly, Tennessee insisted on keeping the 1802 compromise line rather than cede control over a strip of land 113 miles long and varying from two-eight miles in width.

The states ended up settling their boundary through a lawsuit and Tennessee won the case. In 1893, the US Supreme Court ruled in Virginia v. Tennessee that the constitutional requirement to ratify compacts between states was intended to prevent states from making arrangements that bypassed the US Congress and constrained the power of the Federal government. Simply defining a common boundary between two states did not shift any authority away from the Federal government and thus require consent by the US Congress.

The court included in its decision:15

looking east from Cumberland Gap

In Virginia's dispute with Maryland over the boundary along the Potomac River, Virginia had argued that long acceptance of the low-water mark should make it the boundary. Altering the boundary to the technically-correct high-water mark would be too disruptive.

Virginia lost its claim to land in Tennessee by the same rationale. Election districts, tax assessments, and real estate records would not have to be adjusted because the Supreme Court ruled in 1893:16

in 1893, the Supreme Court rejected Virginia's attempt to move the Tennessee boundary

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Virginia-Tennessee Boundary (Plate 99a) digitized by University of Richmond

The court case did clarify the origin of the mysterious notch in the boundary between Tennessee and Virginia in the Blue Ridge. In width the notch extends for over 15 miles, and is about 1.5 miles wide. On the Virginia side is Washington County, and on the Tennessee side are Sullivan and Johnson counties.

When the 1802 line was resurveyed in 1901, the commissioners (who also served as the surveyors, in order to minimize cost) explored east and west of the notch. They looked for blazes on trees in case the Diamond Line surveyors had surveyed a straight boundary between the Holston River and "Steep Rock Creek" in 1802, before moving north and creating their final notch through the Blue Ridge.

The 1901 surveyors were able to find the distinctive diamond blazes from 1802. They found other markings remaining from an 1858 survey, when Virginia and Tennessee had retraced the boundary. However, no marks were found on trees east or west of the zig-zag notch that was created by the decision of the 1802 surveyors to begin at Burnt Hill.17

three different surveys used distinctive marks to identify the Virginia-Tennessee boundary

Source: Lewis Preston Summers, History of Southwest Virginia, 1746-1786, Washington County, 1777-1870 (p.730)

The Virginians on the 1802 compromise survey could have demanded that the starting point be located further south, closer to the latitude of 36° 30'. The Virginia commissioners may have acquiesced to a more-northern starting point because the Burnt Hill area was relatively clear of timber and there were few obstructions for surveyors using line-of-sight tools to mark points.

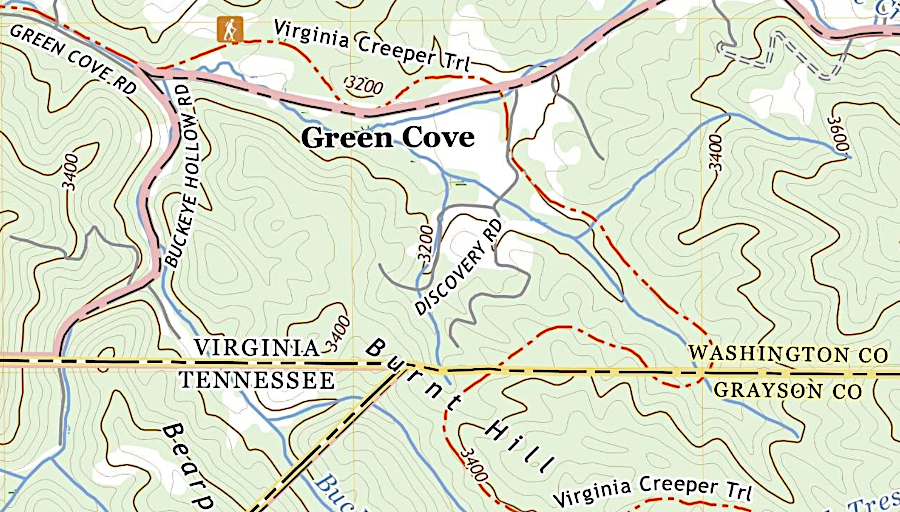

The 1802 decision to start at Burnt Hill meant the eastern end of the Diamond Line was about 1.5 miles north and nearly 1.7 miles east of the western point where Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson had stopped in 1749. A zig-zag boundary was required to connect the end point of the 1779 survey with the starting point of the 1802 survey, and North Carolina ended up with additional territory in the Blue Ridge.

the 1802 survey known as the Diamond Line created created a zig-zag in the Virginia-North Carolina border

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Grayson 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle

the northeastern corner of the notch is at Burnt Hill, near the modern Virginia Creeper Trail

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Grayson NC 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2022)

The notch in the border through the mountains created a large offset in the boundary, but the official reports do not explain why.

One possibility is that once the 1802 Diamond Line surveyors passed through the Blue Ridge, they reached river bottoms in the Holston Valley that were of greater value. The surveyors angled south and got closer to the "correct" latitude, perhaps because the Virginia commissioners were no longer willing to accept a line they recognized as being too far north. As a result of the boundary notch North Carolina gained acreage in the Blue Ridge land, but that mountainous land was steep and in 1802 was of little value for farming.

the 1802 Diamond Line created a notch in the boundary through the Blue Ridge, simplifying the survey challenge and giving North Carolina additional acreage until reaching the higher-value lands in the Holston Valley

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The 1802 report says the surveyors started "on the summit of the mountain generally known as the White Top mountain." In the 1901 resurvey after the US Supreme Court upheld the 1802 boundary line, everyone was confident that the 1802 effort had started from Burnt Hill rather than the summit of Whitetop Mountain. Burnt Hill remains as the northeast corner of Virginia/Tennessee.

Tennessee-Virginia border, with 45-mile long notch east of Bristol

Source: National Atlas

in 1909 the US Geological Survey mapped the eastern edge of the notch using ridgetops, rather than a straight line

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Grayson 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1909)

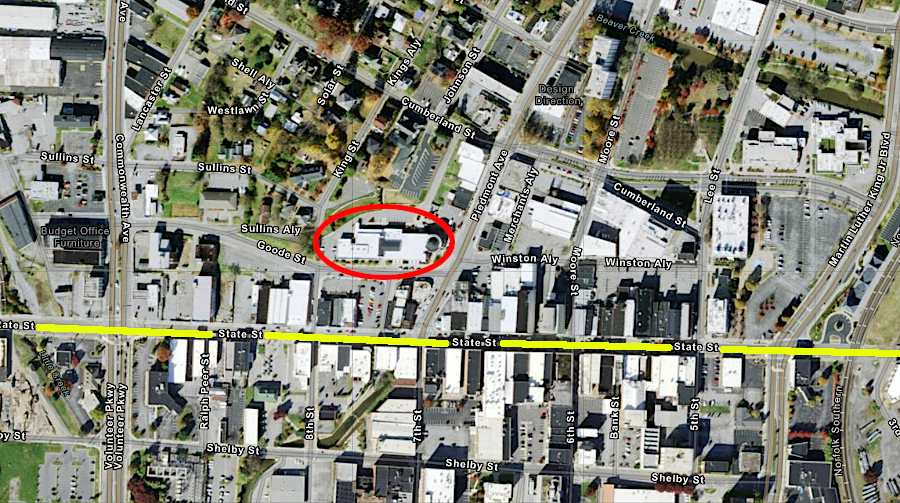

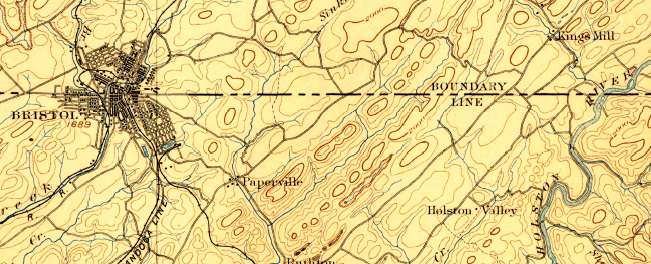

In 1901 Virginia did manage to convince Tennessee to make one adjustment. The 1802 Diamond Line ran through Bristol, which had developed on both sides of the state boundary. (The Virginia side was originally the community of Goodson.) The state line was moved, in a bi-state agreement ratified by the US Congress, from the sidewalk on the northern side of the main street to the middle of the street.

This occurred after the "Water Works War of 1889." That dispute was triggered when a Tennessee-based water company tried to extend its lines to serve customers in Virginia. A Virginia-based officer arrested the company president as he was working on the project. The Virginia-based utility then tried to construct its own pipeline down Main Street. Sheriffs from both Tennessee and Virginia brought their deputies to the scene, and the Tennessee sheriff raised a posse comitatus of several hundred volunteers.

Though violence was a real possibility, the "war" ended in a scene worthy of a Charlie Chaplin comedy episode. The Tennessee sheriff tried to serve a warrant on the Virginia officer who had arrested the president of the Tennessee company. The officer squirmed away, fell into the pipeline ditch - and the sheriff fell in on top of him. Another officer defused the situation, inviting them both to get up and go home until the lawyers could sort it out.18

in Bristol, Virginia flags fly on the north side of State Street and Tennessee flags fly on the south side

Having Bristol split between two states results in confusion when Tennessee and Virginia adopt inconsistent state policies. In 2020, the governors of the two states chose different schedules for reopening businesses after the initial stay-at-home guidance during the coronavirus pandemic. At one point, restaurants on the Tennessee side were open for indoor dining, but on the Virginia side only take-out and delivery were permitted.

Governor Ralph Northam of Virginia had planned to issue reopening guidance which would be applied across the state simultaneously. The circumstances in Bristol led him to reconsider adopting a different recovery schedule, which earlier re-openings allowed on a regional basis, and commented:19

In May 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam issued a mandate for wearing a face mask in public settings. Though Southwest Virginia had relatively few cases at the time, the mandate was applied statewide without an exception for Bristol.

During the last year of President Trump's term, the use of masks as a health protective measure became politicized. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Republican governor in Tennessee never issued a mandate to match what his Democratic equivalent had done in Virginia.

The Virginia governor also imposed limits on the size of public gatherings in order to limit the spread of the COVID-19 coronovirus. State restrictions in Tennessee were looser, allowing larger gatherings. That allowed Virginia-based organizations to schedule events in Tennessee that would not be authorized in Virginia.

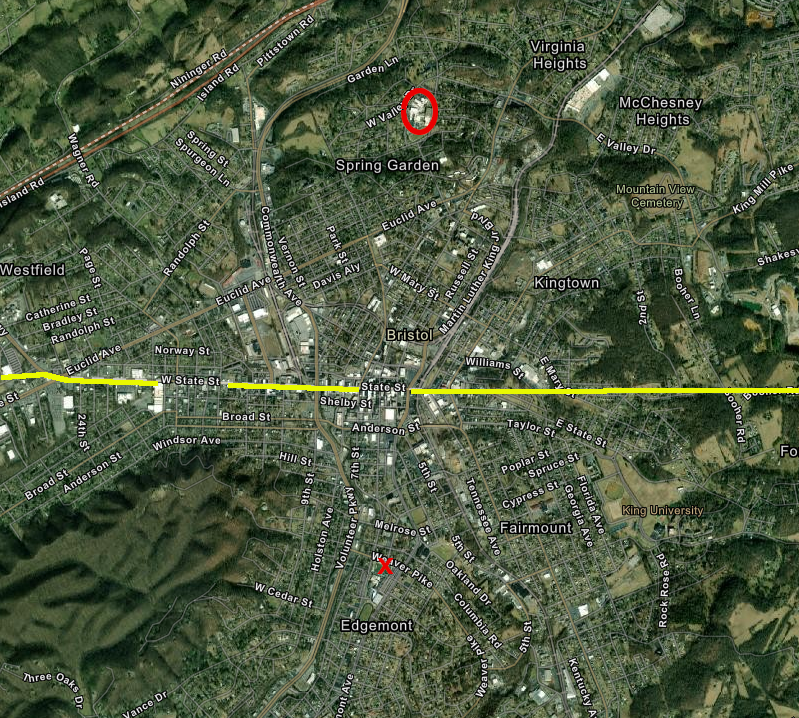

Virginia High School, in Bristol on the Virginia side of the state border, held its 2020 graduation at Bristol Motor Speedway in Tennessee. When Virginia schools launched football games in Spring, 2021, the restrictions in Virginia limited attendance to just 250 spectators. Tennessee allowed up to 2,000 people to attend, and the school board in Bristol, Virginia considered filing suit against Virginia's governor to force a relaxation of the limits.

The decision was to skip the lawsuit and leave the state. Virginia High School opened its delayed 2020 season in 2021 south of the border. The game against Grundy was played in Bristol Municipal Stadium in Tennessee, even though the Bristol (Virginia) School Board had to pay extra to rent the "Stone Castle."20

to avoid COVID-19 restrictions, the Bristol, Virginia high school (red circle) moved its 2021 football game to the Stone Castle (red X) south of the Tennessee-Virginia border

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During the COVID-19 pandemic, different state restrictions affected nightlife in Bristol. At one point, Virginia required bars to close at 10:00pm and patrons to wear a mask. Tennessee allowed bars to stay open until 2:00am, and masks were not required.

Borderline Billiards is located on the Tennessee side of State Street in Bristol

Another distinction in state law caused the Bristol Regional Women's Center in Bristol, Tennessee to open a clinic in Bristol, Virginia. Tennessee banned abortions after the US Supreme Court overturned the Roe vs. Wade decision in 2022, with an exception only if the mother was at risk of death or serious bodily injury. The next closest clinic for Tennessee patients was in Roanoke, 150 miles further north.

As noted in a news story:21

The Bristol Women’s Health attracted 150 patients each month, 90% of whom traveled from states where the procedure had been banned after the Roe vs. Wade decision. The clinic set up a fund to help people who flew into the Tri-Cities Airport in Tennessee get a ride across the border into Virginia.

The city council in Bristol, Virginia quickly modified the zoning ordinance to block more new clinics from opening. The clinic's landlord also tried to break the lease. Both actions were then delayed by lawsuits. As noted by a Catholic priest at a city council meeting:22

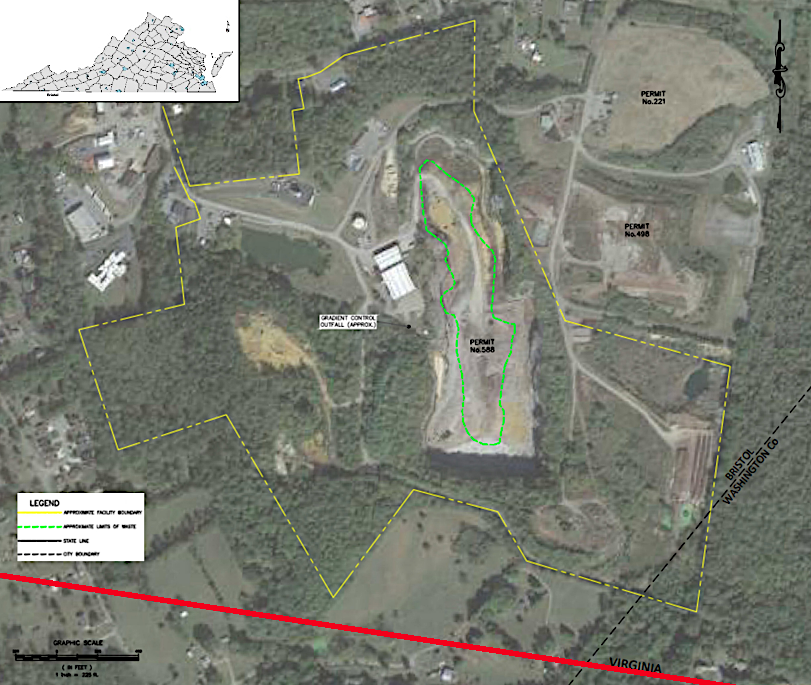

The City Council of Bristol, Tennessee did approve a lawsuit against the Virginia city in 2021. Odors from the Bristol, Virginia landfill disturbed residents on both sides of the state boundary, but the Tennessee officials had no regulatory authority to require corrective action at the facility. The two options for the Tennessee city to force the Virginia city to fund upgrades at the landfill were negotiations and a lawsuit.

One member of the Bristol, Tennessee City Council said, after endorsing preparations for a lawsuit:22

In response, Bristol, Virginia chose to negotiate a settlement rather than fight in the courts. The Virginia city offered to pay a substantial portion of the legal bills incurred by the Tennessee city in preparing the lawsuit. The Virginia city committed to monitor landfill temperatures and install an odor mitigation system if proven to work. After receiving an expert panel's report in 2022, the city signed an agreement with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. It committed to stop depositing waste and to close the landfill.24

the Bristol, Virginia landfill was very close to the Tennessee-Virginia border

Source: Bristol, Virginia, Expert Panel Report: Bristol Integrated Solid Waste Management Facility, Bristol, Virginia (Figure 1)

Having a state boundary run through a city can also provide benefits. The cities of Bristol, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee share a common library system. The Bristol Public Library's Main Branch is on the Virginia side, while Avoca Branch Library is on the Tennessee side of the border. The buildings were the first jointly owned property of the two cities, and the Director of the library reports to two city councils.

There are constant negotiations to determine the fair share of support for the shared library from both parties. Simply arranging for snow removal requires considering the relative contribution of two jurisdictions. At times, however, the library can also tap into two opportunities for support. When the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) offered opportunities for special Federal grants after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bristol Public Library could apply for grants as both a Tennessee and as a Virginia institution.25

it is common to see visitors standing in the middle of State Street to take a picture

The Tennessee border in Southwest Virginia creates a challenge for voting registrars. Most major hospitals are in Tennessee, and deaths there are not recorded in Virginia. As a result, purges of the voting rolls in Virginia jurisdictions are incomplete and dead voters remain in the poll books.

To enhance accuracy, in 2023 the Virginia Department of Elections started to provide registrars data from the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems (NAPHSIS). Access to that multi-state database of vital records enabled registrars to identify voters who had died out of state, and to update poll books accordingly.26

the Bristol Public Library's Main Branch is on the Virginia side of the state line, but is jointly owned by both Bristol, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

presumed NC-VA border, 1779 (assuming a straight line...)

Source: History of the South Carolina cession, and the Northern boundary of Tennessee by William Robertson Garrett (p.2)

at the end of the American Revolution, maps defining the territory of the new United States of America left the extension of Virginia'southern boundary to the imagination

Source: National Archives, An Accurate Map of the United States of America, with Part of the Surrounding Provinces agreeable to the Treaty of Peace of 1783

the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina was not defined until the American Revolution, the boundary between Kentucky-Tennessee was not finalized until 1820 - and Virginia disputed its boundary with Tennessee until 1893

Source: Library of Congress, North America, and the West Indies; a new map, wherein the British Empire and its limits, according to the definitive treaty of peace, in 1763, are accurately described (Carington Bowles, c.1774)

mapmakers as late as 1796 showed a Virginia-Tennessee border extending straight to the Cumberland Mountains, based on the 36° 30' parallel of latitude defined in 1665 to separate Virginia-North Carolina

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the United States exhibiting post roads & distances : the first sheet comprehending the nine northern states, with parts of Virginia and the territory north of Ohio (1796)

the western lands ceded by North Carolina were organized as the Southwest Territory, until Tennessee was admitted into the Union

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, States, Territories, and Cities, 1790 (Plate 61e) and Colonial Towns, 1775 (Plate 61d) digitized by University of Richmond

in 1897, the Holston River had not yet been dammed and flowed freely across the Tennessee-Virginia border

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol 1:250,000 topographic quadrangle (1897)

(from ESRI USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer)