Virginia-North Carolina Boundary

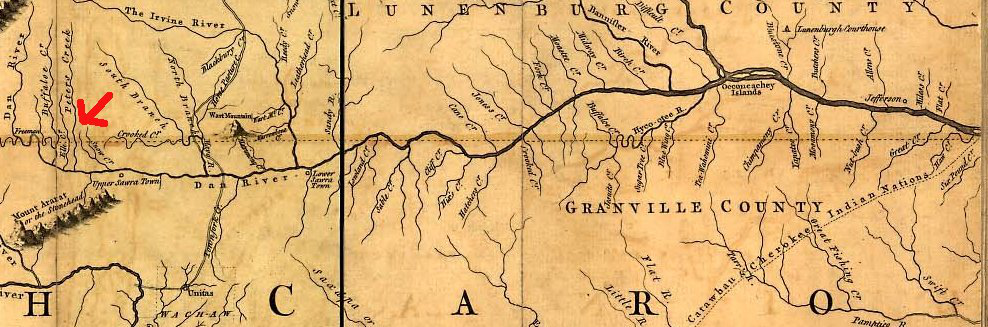

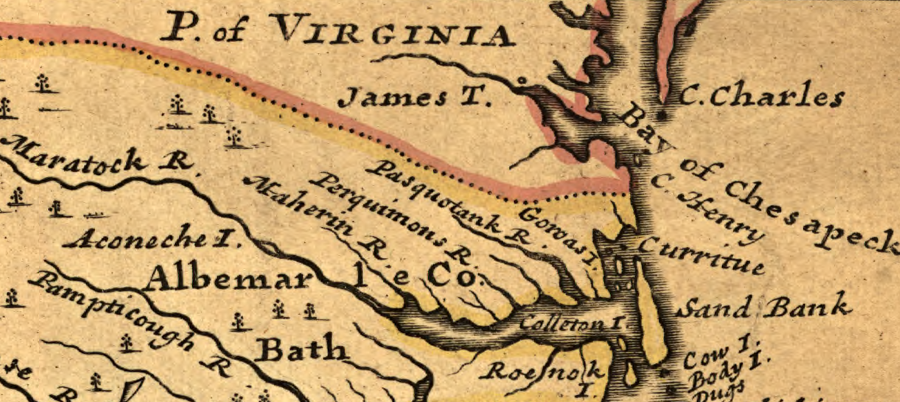

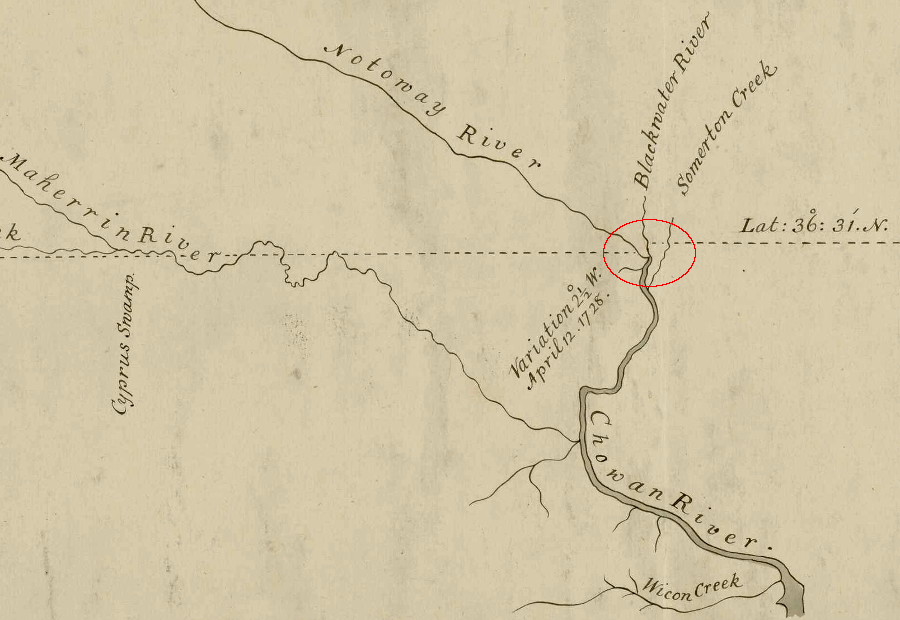

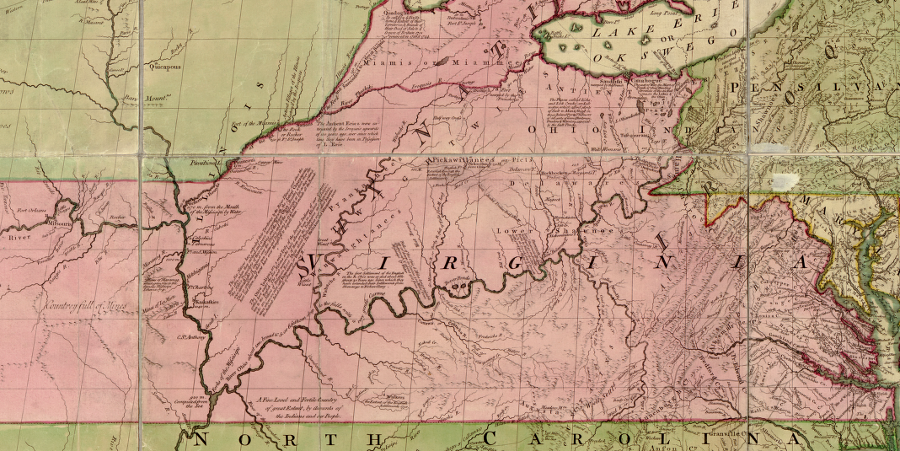

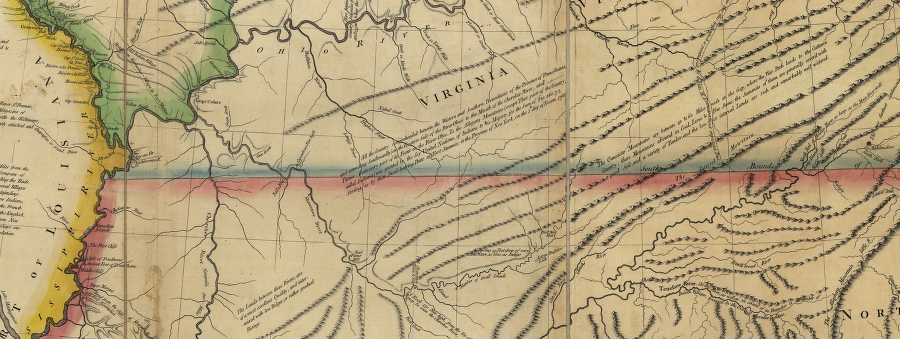

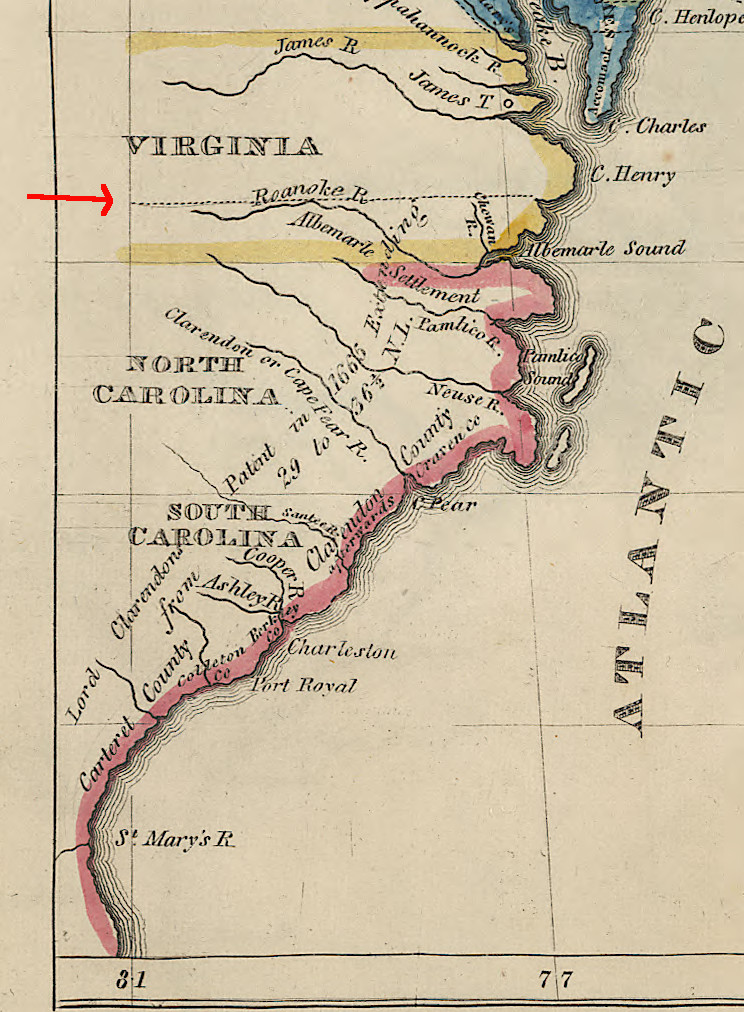

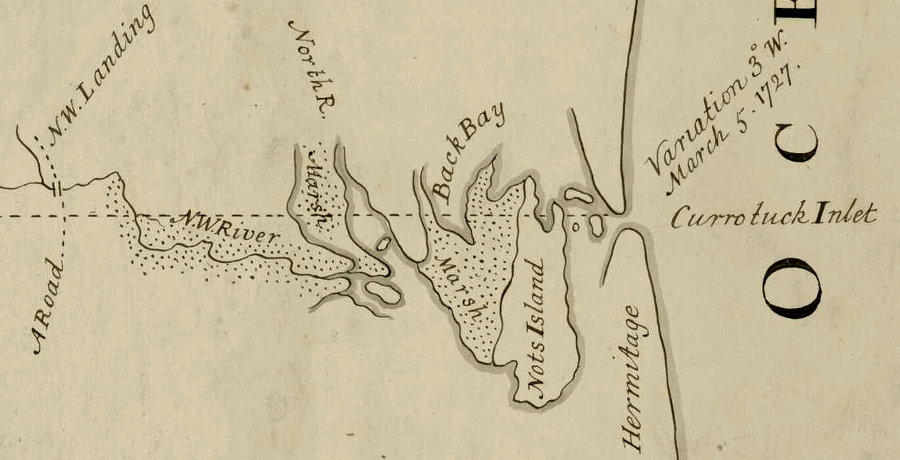

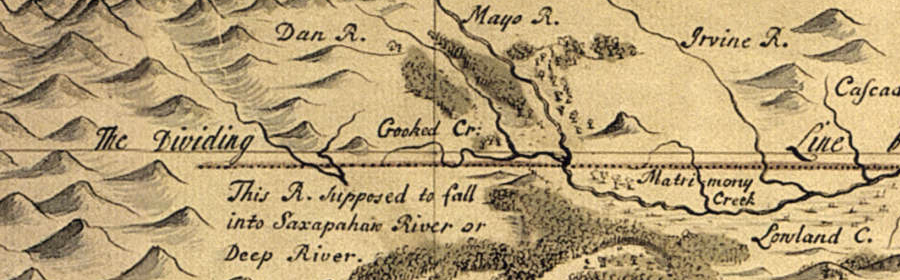

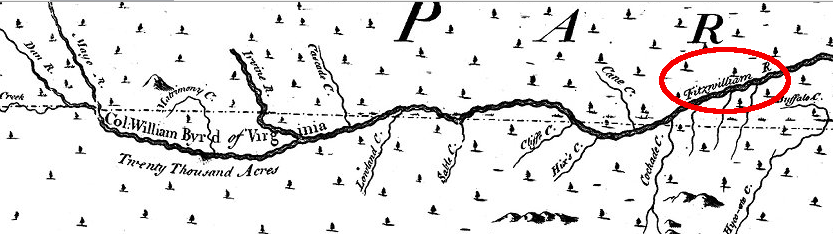

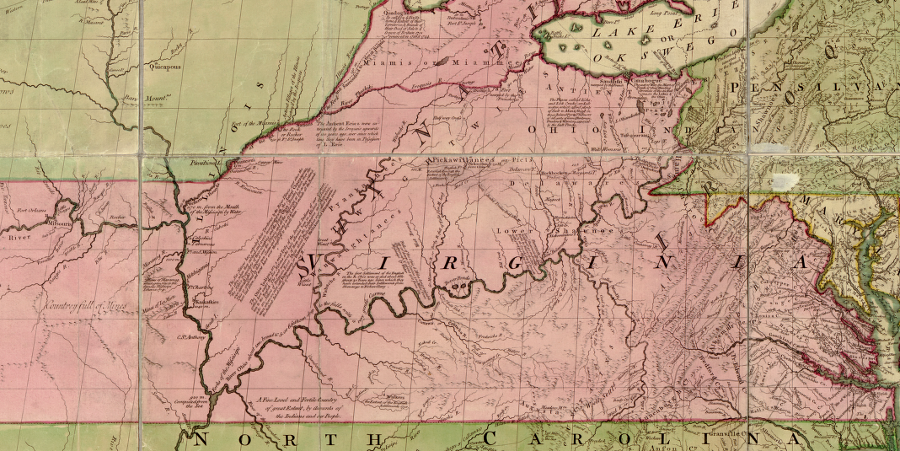

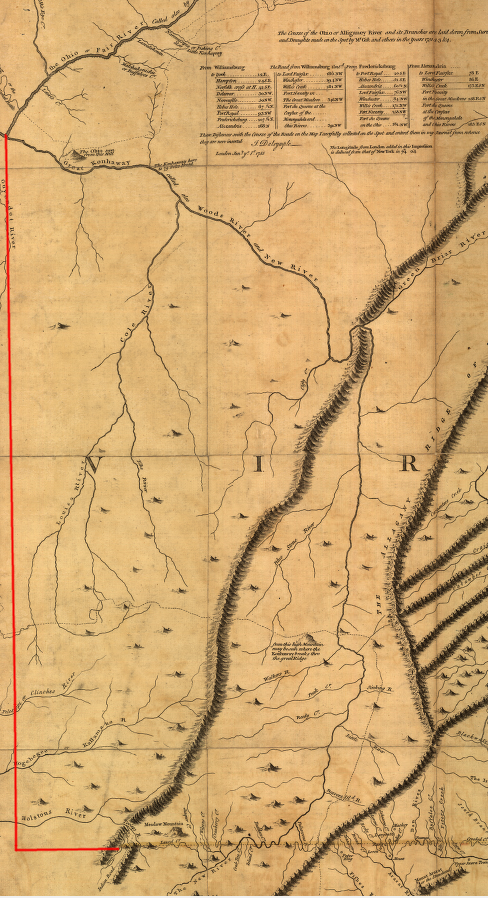

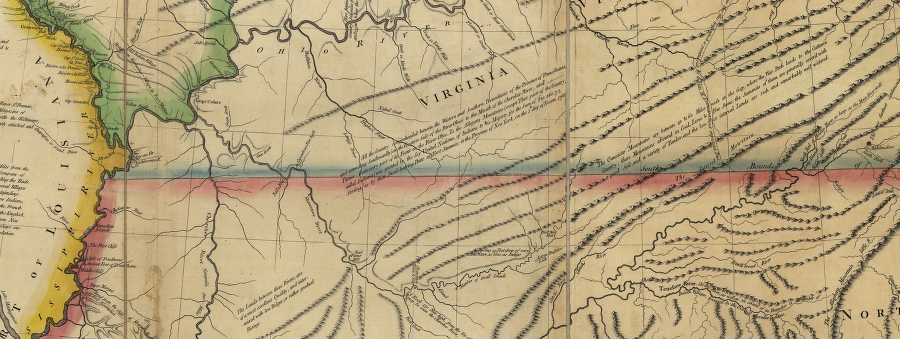

Fry-Jefferson map showing Virginia-North Carolina boundary, from Atlantic Ocean west to Roanoke River (showing notch where boundary line was adjusted at Nottoway River in 1728)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. Drawn by Joshua Fry & Peter Jefferson in 1751

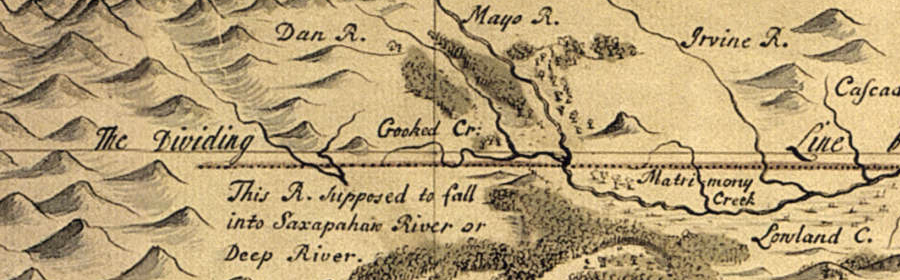

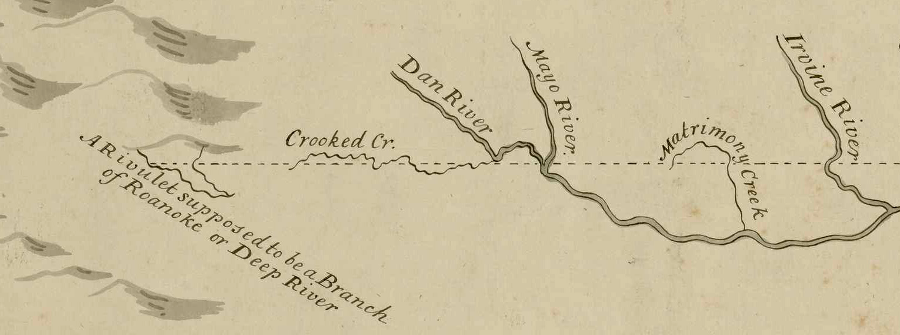

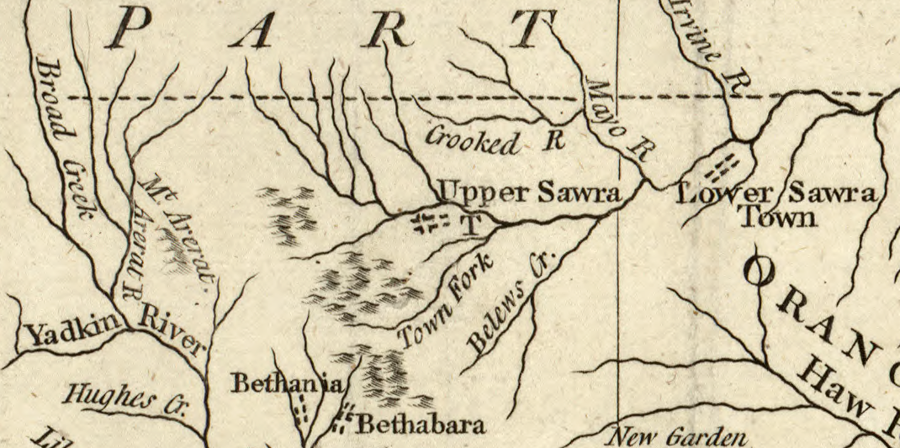

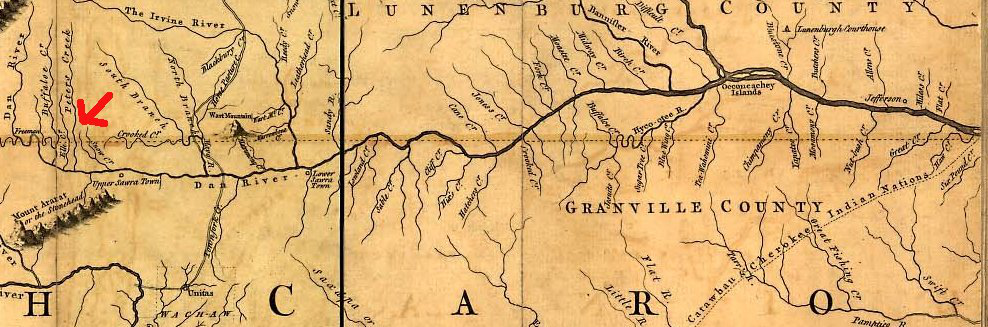

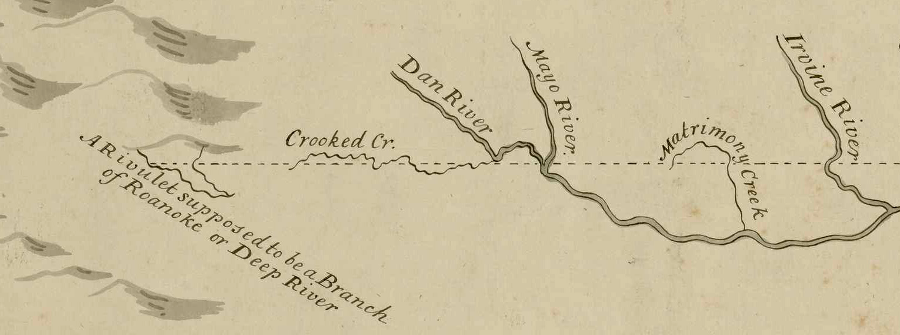

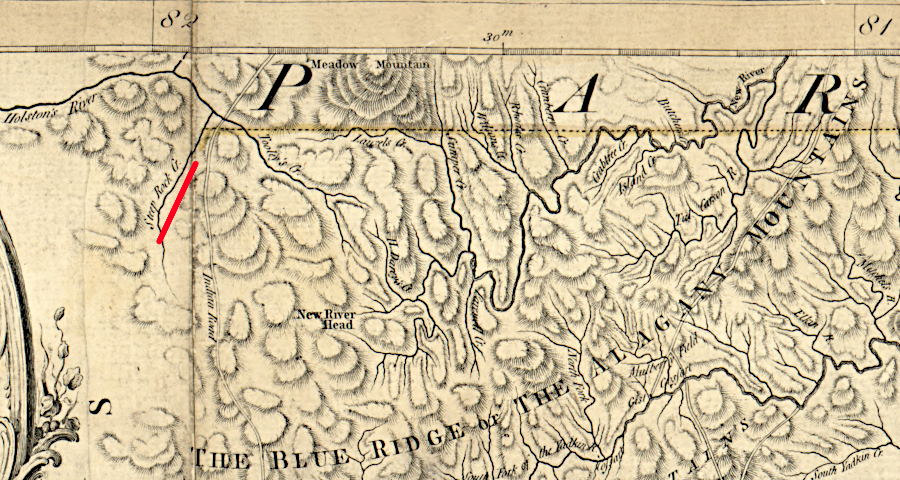

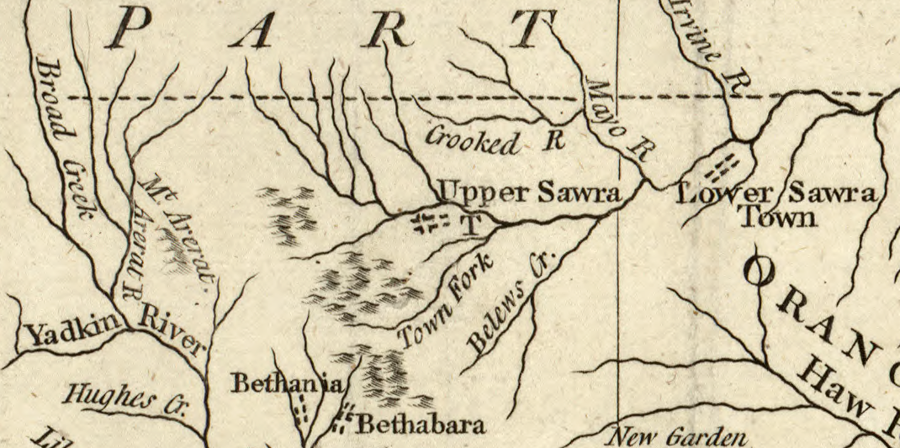

Fry-Jefferson map showing Virginia-North Carolina boundary, from Roanoke River to Dan River (showing Peters Creek where 1749 survey started)

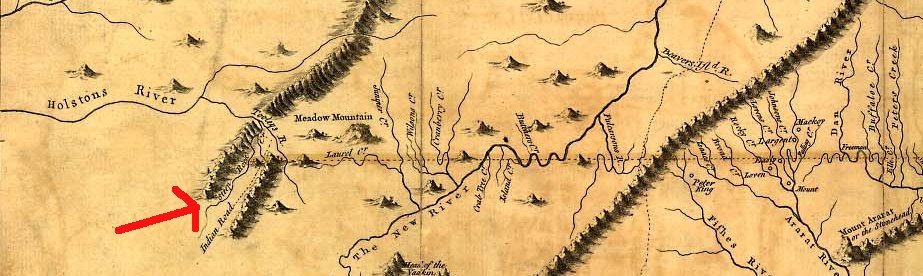

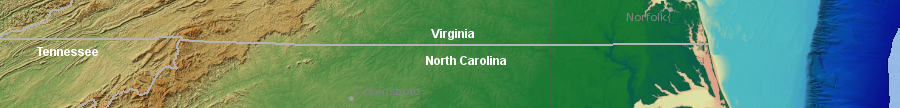

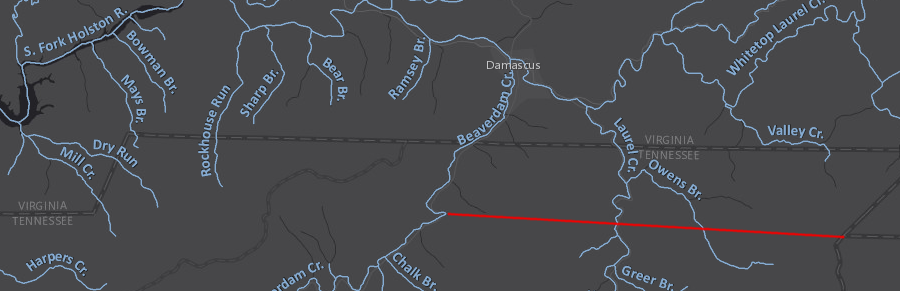

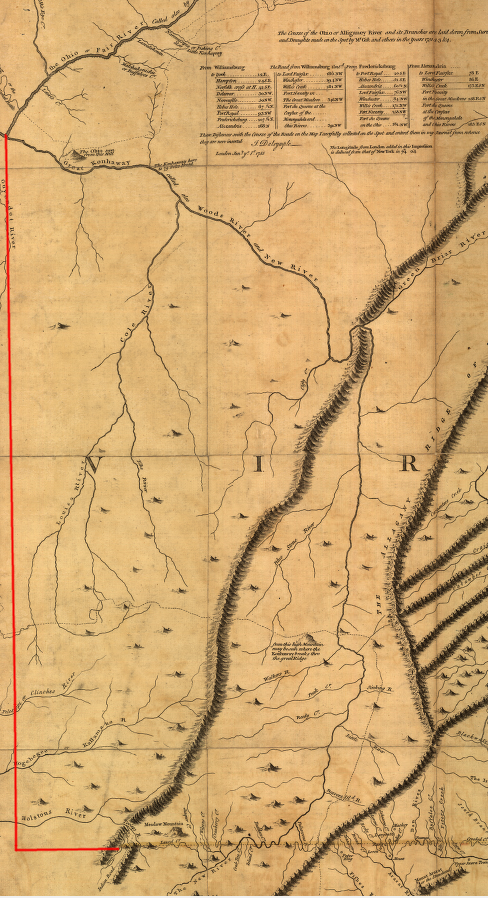

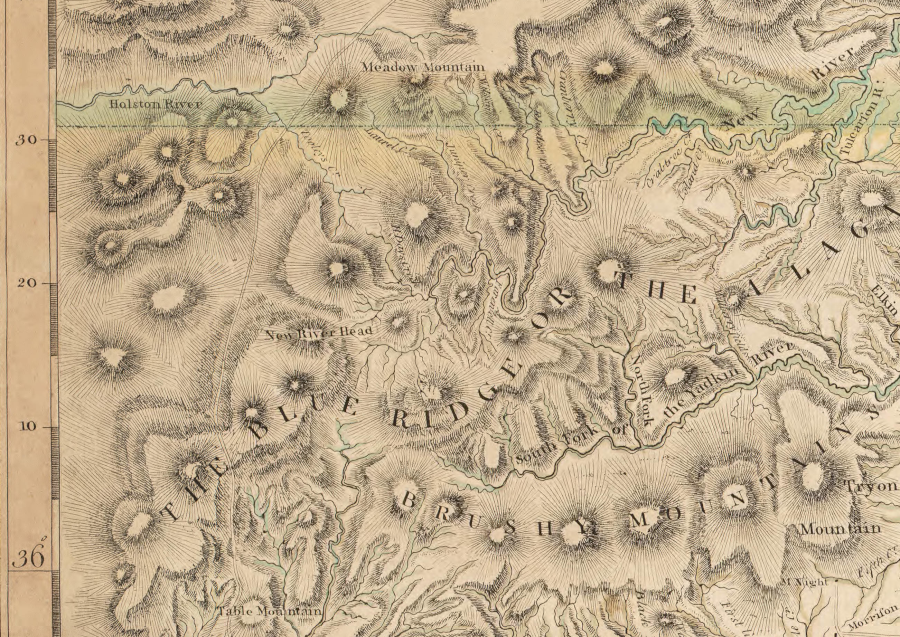

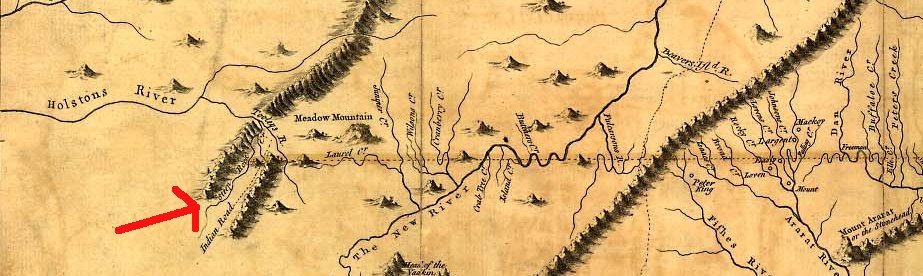

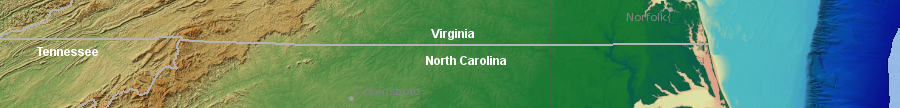

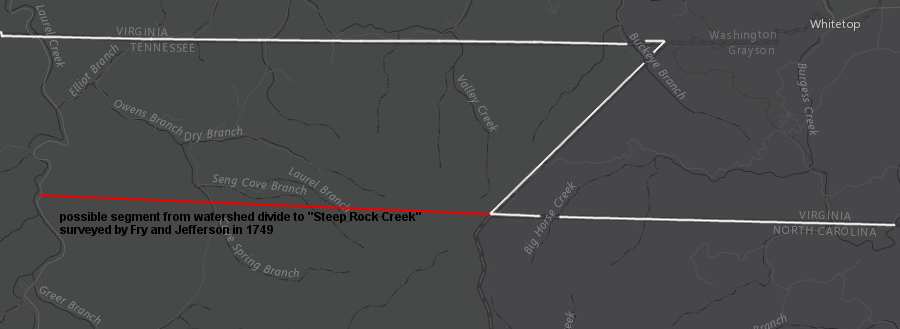

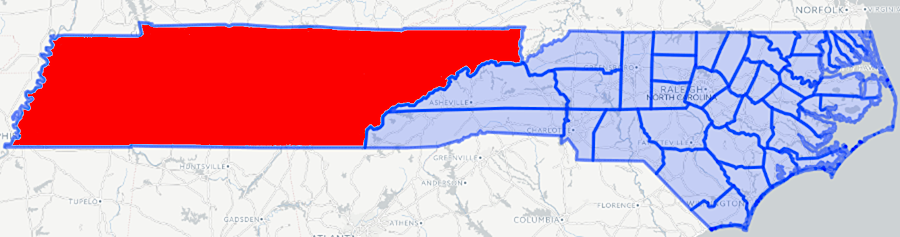

Virginia-North Carolina boundary, as extended in 1749 west to a tributary of the Holston River near modern-day Damascus, Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. (drawn by Joshua Fry & Peter Jefferson in 1751)

When English colonists first attempted to settle in North America, they arrived at what is now Roanoke Island in North Carolina. Those first settlers discovered the area was known as "Wingandacoa" by the current residents - but the English soon decided to call the place "Virginia" after Queen Elizabeth. She had never married, thus avoiding political alliances with France or Spain. The presumption was she had remained a virgin, as an unmarried woman.1

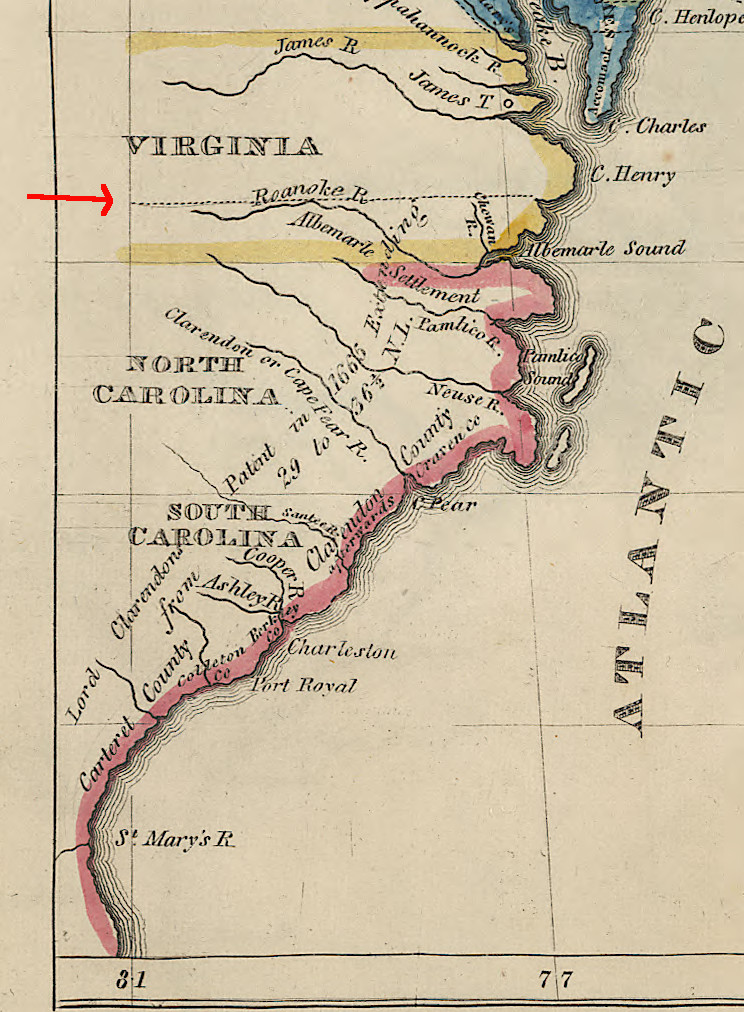

Originally, nearly all of modern-day North Carolina was included in Virginia in the three different colonial charters granted to the Virginia Company. The Second Charter awarded by King James I in 1609 set Virginia's southern boundary at a point 200 miles south of Cape Charles, which ended up being Cape Fear near modern-day Wilmington, North Carolina.

In 1629, King Charles I modified the boundaries of Virginia to create the new colony of Carolana. He gave all land between the 31-36° parallels of latitude, reducing the southern extent of Virginia, to Sir Robert Heath.

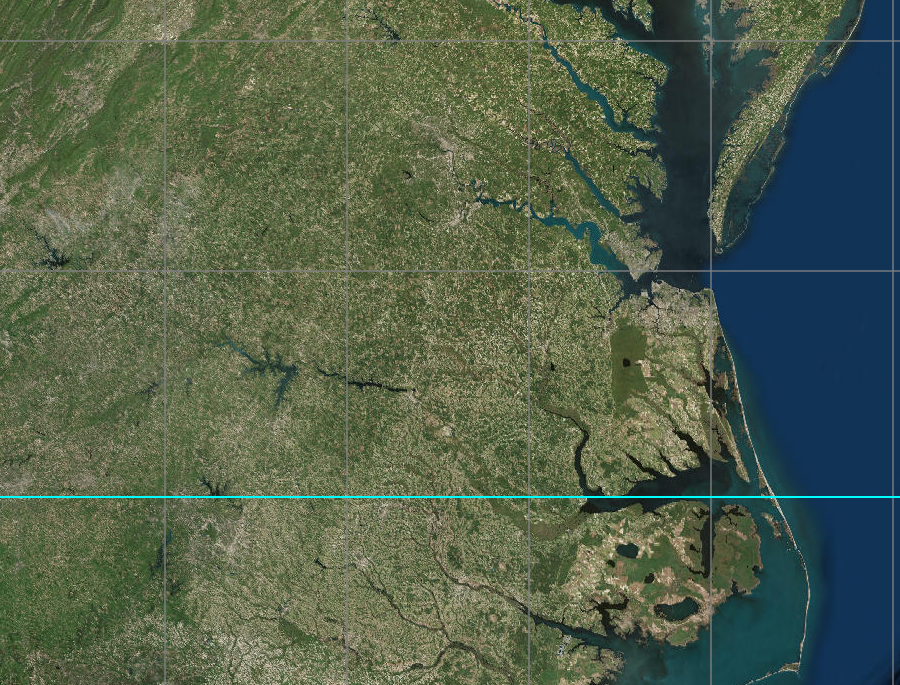

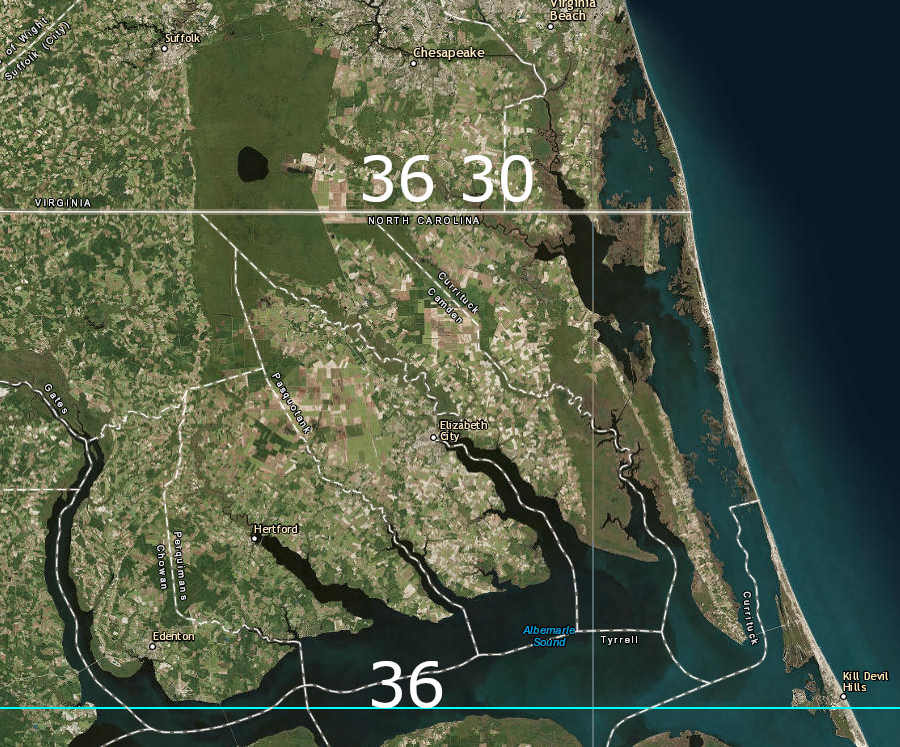

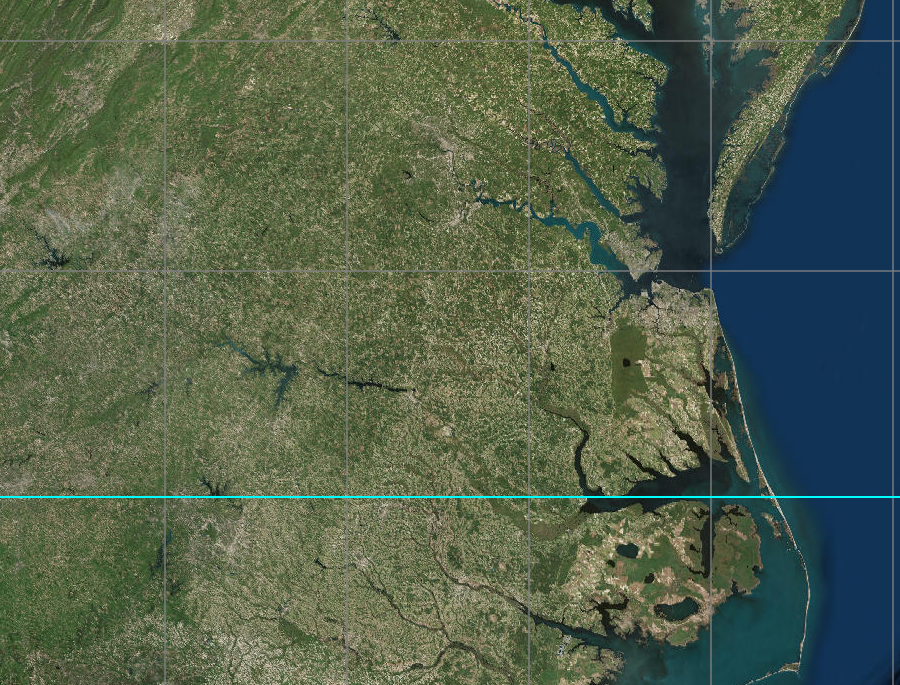

in 1629, the charter for Carolana fixed Virginia's southern boundary at the 36° parallel of latitude

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Since James I had cancelled his grants to the Virginia Company in 1624, King Charles I had clear authority to adjust the boundaries of his royal colony of Virginia in 1629.

Sir Robert Heath was unable to capitalize on the gift, but in 1663 King Charles II made another grant of the territory south of Virginia. He awarded it to eight allies during the English Civil War. The Lords Proprietors of the new colony were Edward Earl of Clarendon, George Duke of Albemarle, William Lord Craven, John Lord Berkley, Anthony Lord Ashley, Sir George Carteret, Sir William Berkley, and Sir John Colleton.

The 1663 grant was for all land between the 31-36° parallels of latitude, but in 1665 Charles II modified it. On the southern end, he extended it from the mouth of the St. Johns River (called the St. Matthias River then) to the 29° parallel of latitude, asserting more control over territory in Florida claimed by the Spanish. The northern boundary was revised to 36 degrees 30 minutes, moving it about 35 miles further north.2

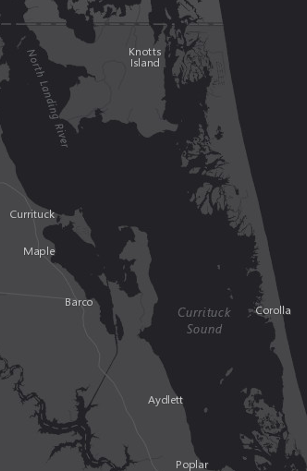

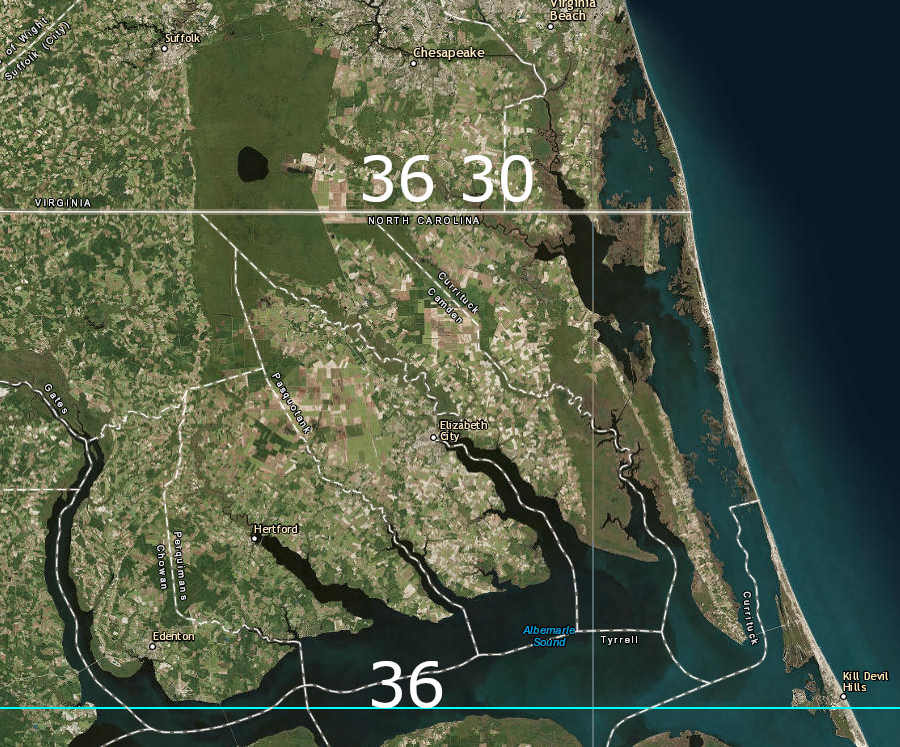

moving the boundary 35 miles north in 1665 from the 36° line gave the Carolina proprietors control over the land near Albemarle Sound

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

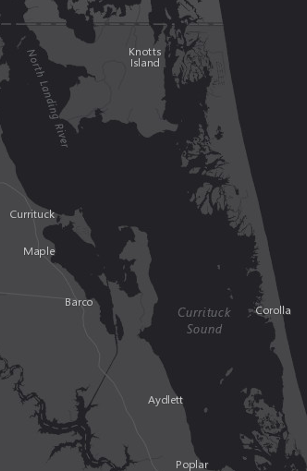

Moving the border a half-degree to the north gave the Lords Proprietors control over the earliest settlers who had already occupied lands on Albemarle Sound, and eliminated potential conflict over control of shipping through that body of water. At the time, Currituck Inlet offered a path through the barrier islands from the northern tip of Albemarle Sound, but later storms shifted sands and have closed that inlet.

This second charter was comparable to the revision of boundaries made in Virginia's Second Charter. That 1609 charter eliminated any confusion regarding the rights granted to the Plymouth Company in the First Charter of 1606. It expanded Virginia's territory to give the London Company complete control over the upper Chesapeake Bay.

Currituck Inlet provided access through the barrier islands in 1770, but is now closed

Source: Library of Congress, A compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey ; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the 1600's, land south of the Elizabeth River in Virginia and north of Albemarle Sound was relatively inaccessible. There was no easy water access to ship tobacco or other products from that area to the Hampton Roads, so Virginia settlement expanded to the north up the York, Rappahannock and Potomac rivers.

In North Carolina, shipping was severely constrained by the lack of reliable passages through the barrier islands. The border region was a backwater, where settlers (including runaway slaves) eked out a meager subsistence living from the land and the hogs they raised. Communities of "maroons" developed, people living apart from the structured society with Anglican churches and legal court processes in colonial Virginia.

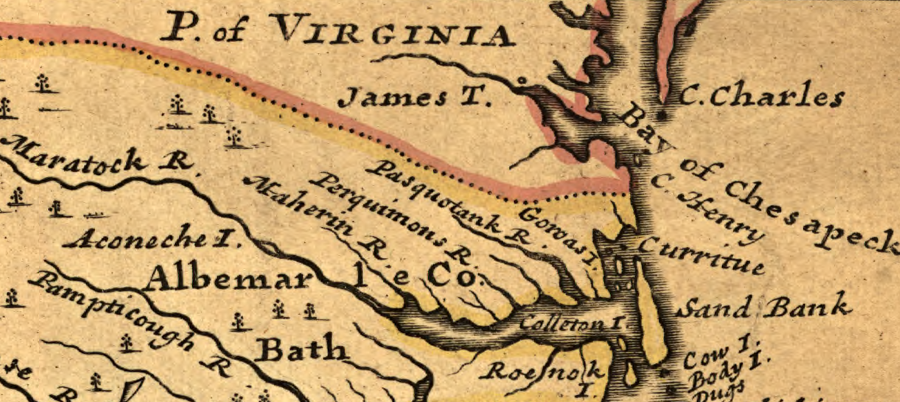

the boundaries of Virginia and Carolina were only loosely understood in 1700

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Marylandia et Carolina: in America septentrionali Brittannorum industria excultae (by Johann Baptist Homann, c.1700)

In 1699, a border dispute involving Crow Island in Albemarle Sound triggered multiple letters between the Carolina and Virginia governors. A Virginia resident had obtained an order from a Princess Anne court regarding a lawsuit against a Carolina resident, and based on that court order Virginia officials seized property in Carolina.

Carolina officials then took an official from Virginia into custody. The Carolinians claimed that officials from Princess Anne County (now the City of Virginia Beach) in Virginia were ignoring not only the border when collecting taxes, but even the legitimate existence of Carolina as a separate colony.3

Crow Island is now part of Currituck National Wildlife Refuge

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia was a royal colony, with government officials in London responsible for appointing officials and approving/rejecting laws. Carolina was a proprietary colony that generated no revenues directly for the government; taxes imposed by the proprietors were private profits. Some colonists might evade paying taxes over which Virginia and London officials had control, by claiming to live below the Virginia-Carolina border.

The London officials on the Board of Trade, from across the Atlantic Ocean, advised the governor of Virginia in 1700:4

- We have considered all you write and the papers you refer to, relating to the fixing of the boundaries between Virginia and North Carolina... take care that those who have settled any lands in those confines upon Virginia Patents be protected against the people of Carolina and that you assert his Maj. right against their encroachments and suffer no innovation therein untill those Boundaries come to be finally settled & determined

the northern border of North Carolina was not clearly understood at the start of the 1700's

Source: Library of Congress, A series of maps to Willard's History of the United States, or, Republic of America (Emma Willard, 1828)

During the following decade, the Virginia and Carolina governments wrote reports to the Board of Trade that resemble the complaints of young children asking an adult to resolve their conflict. Virginia even sponsored a secret survey to determine if the mouth of the Meherrin River was at 36 degrees 30 minutes, and how locating the line would affect existing property owners.5

In 1710, the governors of Virginia and Carolina appointed surveyors (plus members of the gentry to serve as commissioners, who would represent each colony's interests during the surveys) to mark the northern boundary line. That line was defined clearly in the 1665 Carolina charter:6

- the north end of Currituck river or inlet, upon a strait westerly line to Wyonoak creek, which lies within or about the degrees of thirty-six and thirty minutes, northern latitude; and so west, in a direct line, as far as the South-Seas

not every mapmaker acknowledged that the Virginia-North Carolina border was a straight line based on latitude, rather than natural features

Source: Library of Congress, Carolina by Herman Moll (1732)

However, the 1710 attempt to survey and mark the Virginia-Carolina boundary was a complete failure. The commissioners agreed on nothing, so no useful boundary lines were surveyed.

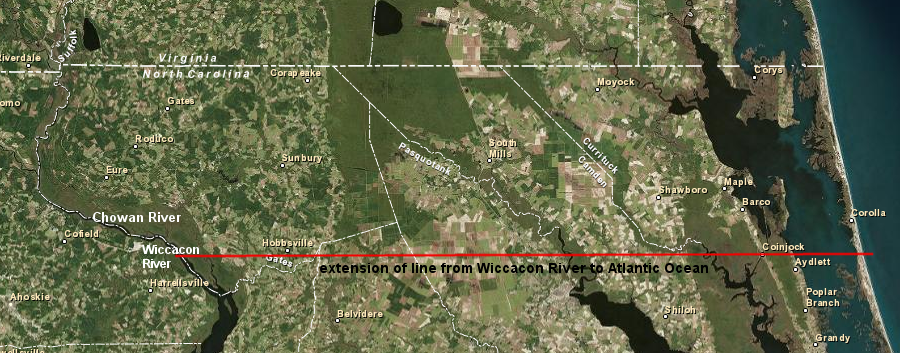

Based on testimony by local residents, the Virginia commissioners decided that the creek known as Wyonoak/Weyanoak/Weycocon/Wicocon was the location identified in the 1665 charter. Carolina's commissioners disagreed. They argued that the Native Americans for whom the Weyanoak was named had moved around, and the line should run due west to intersect the mouth of the Nottoway River. The North Carolina surveyors claimed that if the Virginia approach was adopted, the border would move 15 miles south of the 36° 30' line of latitude.

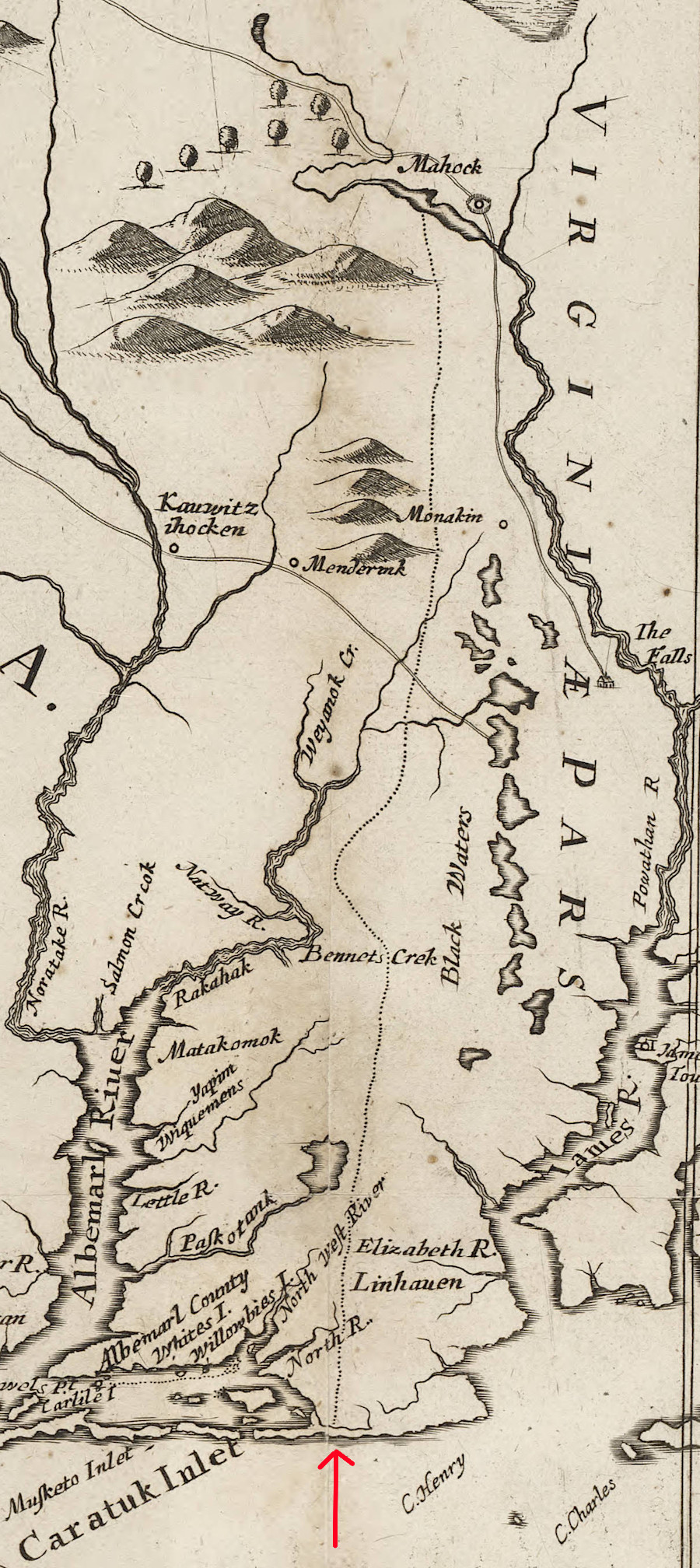

a 1671 map sketched out a Virginia-Carolina border running from Currituck past Weyanoak Creek to a point on the James River upstream of the confluence with the Rivanna River

Source: North Carolina Maps, A new discription of Carolina by the order of the Lords Proprietors (John Ogilby, ~1671)

The Virginia surveyors may have brought an inaccurate quadrant, or may have been inadequately trained to use their equipment. They claimed the mouth of the Nottoway River was at 37° latitude and all the blame for the failed 1710 survey could be assigned to one North Carolina official.

if the 1728 surveyors had gone "upon a strait westerly line to Wyonoak creek" and then due west, Virginia would have extended 15 miles further south

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North and South Carolina with their Indian frontiers (by Henry Mouzon, 1775)

The Virginians claimed that Edward Moseley "started all the captious Arguments and Exceptions that could be." The Virginians also objected to the local witnesses recruited by the North Carolinians. Those witnesses swore that the Nottoway River was traditionally known as Weyanoak Creek, so the boundary line should be located at the mouth of the Nottoway River rather than further south. The Virginians claimed that Moseley misrepresented the statements in his documentation, that those locals were not honest, and that there were significant conflicts of interest that affected the testimony:7

- Their Witnesses are all very ignorant men & most of them men of ill fame that have run away from Virginia & some of them concerned in Interest & we plainly discover several of them did not understand what they swore in their Affidavits & we observe that all of them contradict themselves or one another.

Currituck Inlet was the starting point for defining the Virginia-North Carolina boundary

Source: Library of Congress, A new & accurate map of the provinces of North & South Carolina, Georgia &c. by Emanuel Bowen (1752)

The Virginia commissioners accused the Carolinians of deliberately sabotaging the survey effort by interfering in testimony regarding the historic location of "Wyonoak" creek, and lying about the availability of survey tools that would corroborate the results of the Virginia instruments. The Virginia commissioners surmised that Moseley had patented property that could be across the border in Virginia, while the other North Carolina commissioner (John Lawson) would lose some surveying business if the line was marked.

if the Virginians had prevailed in defining the identity of Weyanoak Creek and used it as the point of beginning for the 1710 boundary survey, Corolla on the Outer Banks would be in Virginia today

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The border region, where the colonial boundary and government responsibilities were unclear, became a no-man's-land. Colonial officials could not determine who was authorized to enforce the law, so county sheriffs were at risk of not getting paid if they invested effort in dealing with border residents. Settlers near the border found it convenient to avoid paying taxes to either colony. Though Virginia and North Carolina agreed not to issue grants of land in the disputed area, Virginians felt that North Carolina was less strict in its compliance with the deal.

While the boundary was undefined, Governor Spotswood complained in 1714 that "...loose and disorderly people daily flock here" In 1728, William Byrd II was a Virginia commissioner overseeing the survey of the North Carolina-Virginia boundary. In Byrd's "secret history" of the dividing line survey, he expressed the contempt of the Virginia elite for the poor North Carolina residents living in the backcountry:8

- Surely there is no place in the World where the Inhabitants live with less Labour than in N Carolina. It approaches nearer to the Description of Lubberland than any other, by the great felicity of the Climate, the easiness of raising Provisions, and the Slothfulness of the People.

- ...they loiter away their Lives, like Solomon's Sluggard, with their Arms across, and at the Winding up of the Year Scarcely have Bread to Eat. To speak the Truth, tis a thorough Aversion to Labor that makes People file off to N Carolina, where Plenty and a Warm Sun confirm them in their Disposition to Laziness for their whole Lives.

in 1720, the boundary between Virginia and the Carolina colonies was not clear

Source: Library of Congress, A new and accurate chart of the West Indies with the adjacent coasts of North and South America (by Emanuel Bowen, 1720?)

Escaped slaves also took advantage of the lack of law enforcement. In 1728, William Byrd visited with a family that claimed to be free, but he suspected were runaways:9

- we came upon a family of mulattoes that called themselves free, though by the shyness of the master of the house, who took care to keep least in sight, their freedom seemed a little doubtful. It is certain many slaves shelter themselves in this obscure part of the world, nor will any of their righteous neighbours discover them.

The Virginia-North Carolina border was resolved in two major joint survey efforts in 1728 and 1749.

In 1728, the colonial governors of Virginia and North Carolina agreed to survey the boundary again. At the time, North Carolina's settlement was concentrated around Albemarle Sound. Edenton, near the mouth of the Chowan River, was the colony's largest city with 60 houses.

That effort started at the Atlantic Ocean, and surveyors went westward 237 miles until reaching the edge of European settlement beyond the Dan River. The most prominent member of that effort was William Byrd II, who documented in a highly-opinioned history of the survey what was an adventure for him.

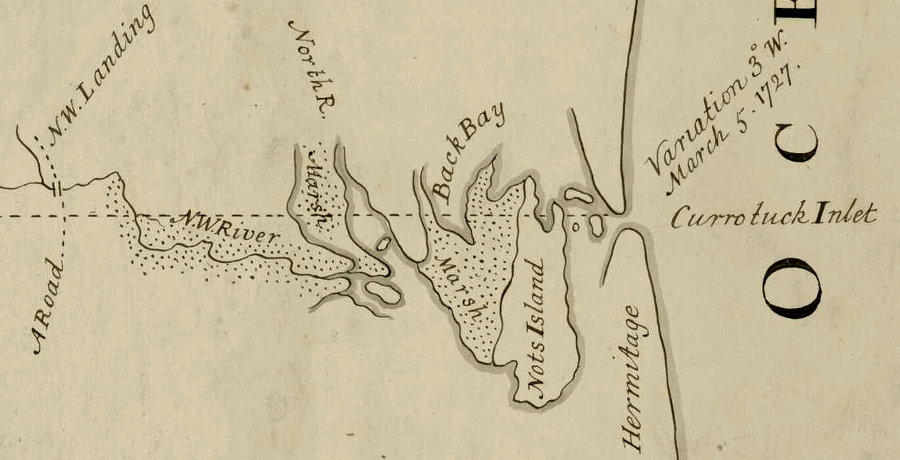

The surveyors and commissioners gathered in February, 1728 at what is now the southeastern corner of Virginia's False Cape State Park. In a repeat of the 1710 survey, the Virginians made a hard-to-substantiate claim at the very beginning. As Byrd reported later in The History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina:10

- ...the first question was, where the dividing line was to begin. This begat a warm debate; the Virginia commissioners contending, with a great deal of reason, to begin at the end of the spit of sand; which was undoubtedly the north shore of Coratuck inlet. But those of Carolina insisted strenuously, that the point of high land ought rather to be the place of beginning, because that was fixed and certain, whereas the spit of sand was ever shifting, and did actually run out farther now than formerly. The contest lasted some hours, with great vehemence, neither party receding from their opinion that night.

the 1728 boundary survey started with a dispute over the eastern point at Currituck Inlet, where the dividing line was to begin

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the boundary between Virginia and Carolina laid out by His Majesty's order and assent of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina in the year 1728 (by William Mayo, 1728)

Once again Edward Moseley represented North Carolina, this time as both a commissioner and as a surveyor, but he was willing to adapt to the situation. Byrd thought the authority of the Virginia surveyors to proceed independently, if necessary, helped create a willingness on the part of the North Carolina side to compromise and agree the next morning on a starting point.

The surveyors drove a cedar post into the sand at a location 200 yards further north than the Virginians had proposed the previous day, stablishing a point of beginning. On March 5, 1728, they aligned their compasses to account for the variation between magnetic and true north. Using the Pole Star and the first star in the "Tail of the great Bear," they determined the compasses were 3° off true north and they had to survey the line towards 87° West.

On March 6, they measured the declination of the sun and determined the latitude of Currituck Inlet was 36° 31' 13" north of the equator, and started west across the marshes and islands of the Coastal Plain.

a cedar post was drive into the sand at Currituck to mark the starting point of the Dividing Line survey in 1728

Source: Library of Congress, A compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey (1770)

At times, according to Byrd, the surveyors walked in mud up to their knees. They struggled to find a place to camp overnight where the swampy ground "made a fitter lodging for tadpoles than men."

The professional surveyors and their chainmen took the physical difficulties as a challenge, and competed to be the first to march through the uncharted Dismal Swamp. The commissioners chose to bypass that part of the survey and traveled around the edge to the other side. It took several days for the surveyors to emerge, starving and exhausted from the crossing of the Dismal.

Eight years earlier in 1720, two North Carolinians had reported to the Board of Trade in London that the local population was so rough that the territory near Dismal Swamp should be declared part of Virginia in order to establish colonial authority:11

- this place is the receptacle of all the vagabouns & runaways of the main land of America for which reason and for their entertaining Pirates they are justly contemned by their neighbours, for which reason and that they may be under good Government and be made usefull to the rest of his Majesty's Collonys it would be proper to joyn the same again to Virginia

In 1728, William Byrd II also found little reason to respect the inhabitants, commenting:12

- they are devoured by mosquitoes all the summer, and have agues every spring and fall, which corrupt all the juices of their bodies, give them a cadaverous complexion, and besides a lazy, creeping habit, which they never get rid of.

The land in the southeastern corner of Virginia/northeastern corner of North Carolina was productive, but inaccessible to shipping from Europe due to the barrier islands. Byrd commented on both the geography and how the survey would impact the landowners:13

- It would be a valuable tract of land in any country but North Carolina, where, for want of navigation and commerce, the best estate affords little more than a coarse subsistence...

- The line cut two or three plantations, leaving part of them in Virginia, and part of them in Carolina. This was a case that happened frequently, to the great inconvenience of the owners, who were therefore obliged to take out two patents and pay for a new survey in each government...

- The line cut William Spight's plantation in two, leaving little more than his dwelling house and orchard in Virginia. Sundry other plantations were split in the same unlucky manner, which made the owners accountable to both governments. Wherever we passed we constantly found the borderers laid it to heart if their land was taken into Virginia: they chose much rather to belong to Carolina, where they pay no tribute, either to God or to Caesar. Another reason was, that the government there is so loose, and the laws are so feebly executed, that, like those in the neighbourhood of Sidon formerly, every one does just what seems good in his own eyes.

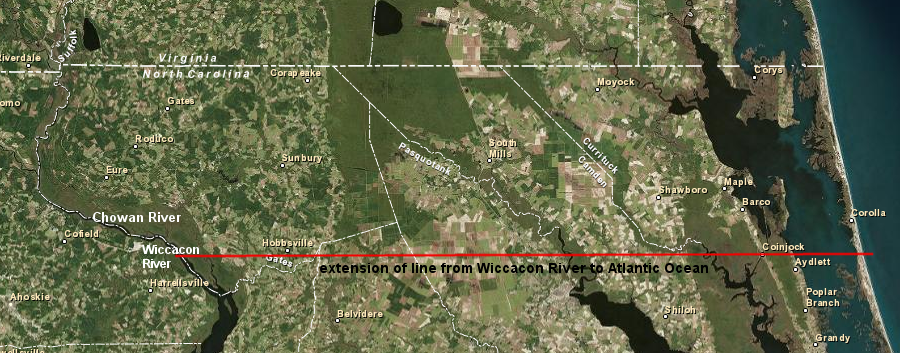

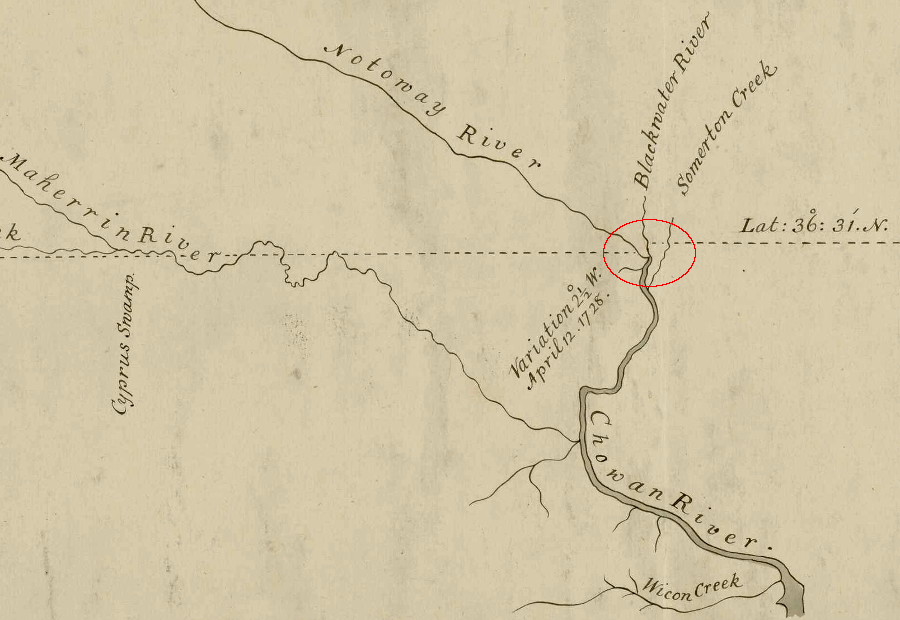

After reaching the Blackwater and Nottoway rivers, it was clear that the key 1710 claim by the Virginia commissioners was not correct. The Nottoway River would be the "Wyonoak creek" referenced in the 1665 charter, not the Wiccacon River/Veecaunes Creek that flowed into the Chowan River much further south.

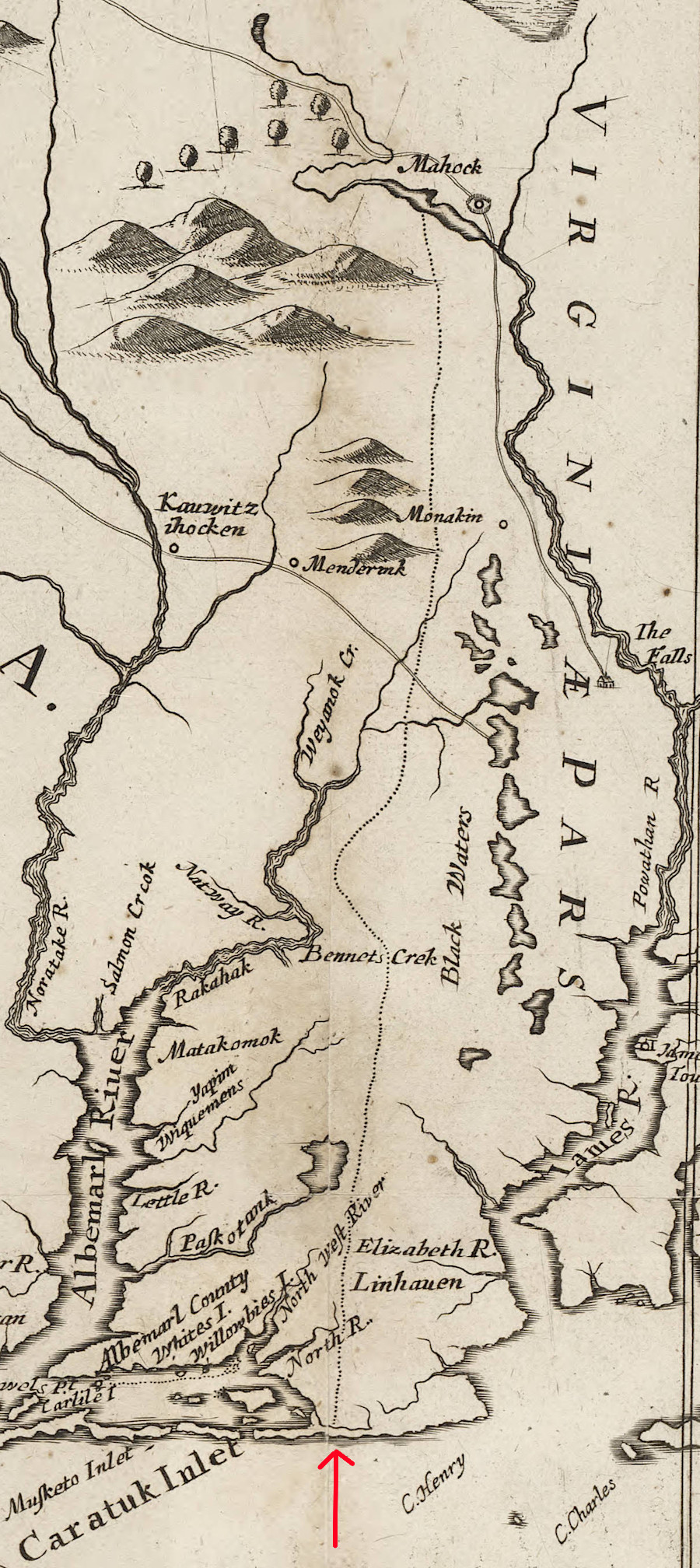

According to the instructions issued by governors Spotswood and Eden in 1716 for the resolution of the boundary issue, after encountering the Blackwater River the surveyors moved half a mile south to the confluence with the Nottoway River (i.e., the headwaters of the Chowan River) and then began surveying straight to the west again:14

- That if the said West Line cuts Blackwater River to the Northward of Nottoway River; then from that point of Intersection, the Bounds shall be allowed to continue down the middle of the said Blackwater River to the middle of the Entrance into the Nottoway River, and from thence a Due West Line shall divide the said two Governments.

after reaching the Blackwater River, the 1728 surveyors marking the dividing line between Virginia-Carolina moved south to the mouth of the Nottoway River before heading west again

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the boundary between Virginia and Carolina laid out by His Majesty's order and assent of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina in the year 1728 (by William Mayo, 1728)

the adjustment, moving south to the confluence of the Nottoway and Blackwater rivers, still resulted in a boundary located slightly north of the 36° 30.5' line of latitude

Source: East Carolina University, New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina

(1733)

The confluence was identified as being at 36 degrees 30.5 minutes - slightly north of the line defined in the 1665 charter. Even though the surveyors moved south to the confluence with the Blackwater, North Carolina received a small amount of additional land as the survey headed west again. The instructions from the governors had directed that the surveyors use specific natural features (such as the confluence) rather than the mathematical lines of latitude to mark the border.

the Virginia-North Carolina border was defined in 1665 as the 36° 30" parallel of latitude, but that was adjusted as the boundary was finally surveyed

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric and Digital Elevation Models

After completing over 70 miles of surveying to the Meherrin River, the party took a break between April-September 1728. According to William Byrd II's description of the September-October survey effort, on good days they could mark 7-8 miles of surveyed line but on other days covered only 4 miles.15

the North Carolina map produced after the survey suggests the boundary shifted north, after crossing the Nottoway River

Source: North Carolina Maps, A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina drawn from the Original of Colo. Mosely's (1737)

The Carolina commissioners and surveyors participated for only two weeks in the Fall, 1728 effort. By that time, they claimed to have extended the survey well beyond existing settlement, but most of the Virginians felt the survey should continue because new settlers would soon arrive in the region. Unless the line was marked, settlers would claim to be in North Carolina and avoid paying Virginia taxes.

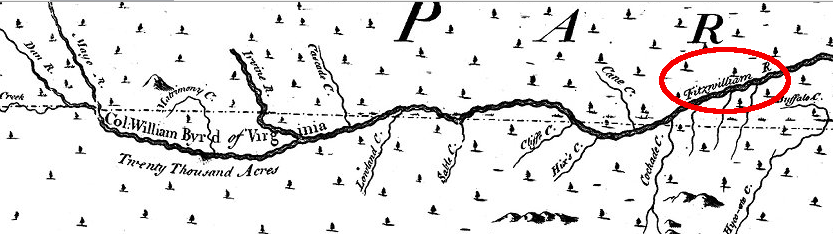

One Virginia commissioner, Richard Fitzwilliam, also chose to leave after October 5, 1728. As described by William Byrd, Fitzwilliam was scheduled to participate as a justice on the General Court in Williamsburg and would not receive his salary if not in attendance. In addition, the party had drunk all of its alcohol:16

- In the afternoon Mr. FitzWilliam, one of the Commissioners from Virginia, acquainted his colleagues it was his opinion that by his Majesty's Order they could not proceed farther on the line but in conjunction with the Commissioners of Carolina, for which reason he intended to retire the next morning with those gentlemen. This îookt a little odd in our Brother Commissioner, tho' in justice to him, as well as our Carolina Friends, they stuck to us as long as our good Liquor lasted, and were so kind as to drink our good journey to the Mountains in the last bottle we had left.

Edward Moseley, one of the North Carolina commissioners during the 1728 survey, created a map in 1733 that did not indicate clearly where the surveyors stopped

Source: North Carolina Maps, A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina drawn from the Original of Colo. Mosely's (1737)

Over the protests of the Carolinians, the Virginians continued the survey. At the Dan River, the Virginia commissioners and surveyors finally spotted the Blue Ridge in the distance.

They crossed Matrimony Creek (according to Byrd, "called so by an unfortunate married man, because it was exceedingly noisy and impetuous"), and pushed on until they ran out of forage for the horses and wild game for the men. By October 26, 1728, the surveyors' had made their last blaze, on a red oak near Peters Creek (a tributary of the Dan River in modern Patrick County).17

According to their calculations, the expedition had traveled 237 miles west from the cedar post planted at the starting point on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, and 64 miles past the point where the Carolina commissioners had left.18

the 1728 boundary survey ended in the foothills of the Blue Ridge, west of Matrimony Creek

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the boundary between Virginia and Carolina laid out by His Majesty's order and assent of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina in the year 1728 (by William Mayo, 1728)

Byrd's party considered returning home by riding north to the headwaters of the James River. That would have enabled them to determine if the Sharantow (Shenandoah) stretched south all the way to the Roanoke River, and if a lake was at the headwaters of the Roanoke, Shenandoah, and "another wide branch of Mississippi" (the New River). The food shortage convinced them to return along the survey line they had just marked, taking a known path rather than exploring the unknown.19

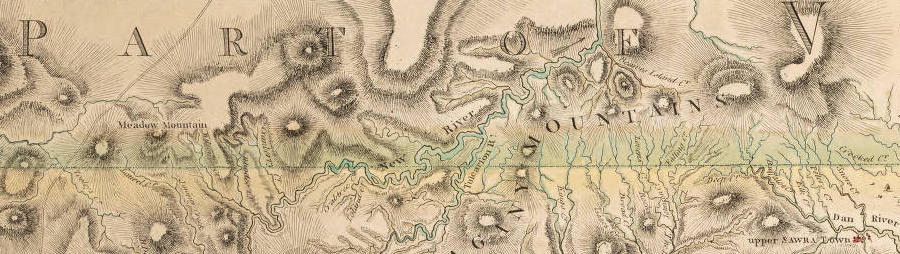

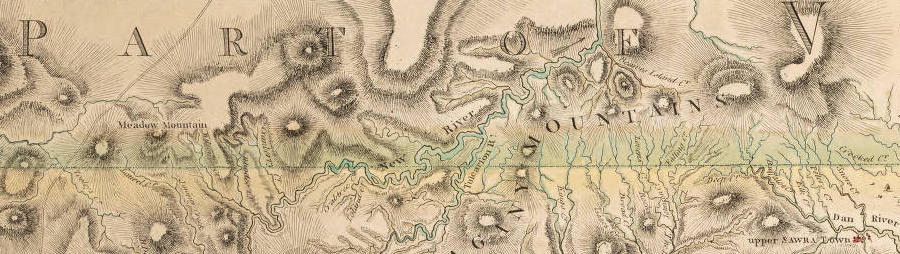

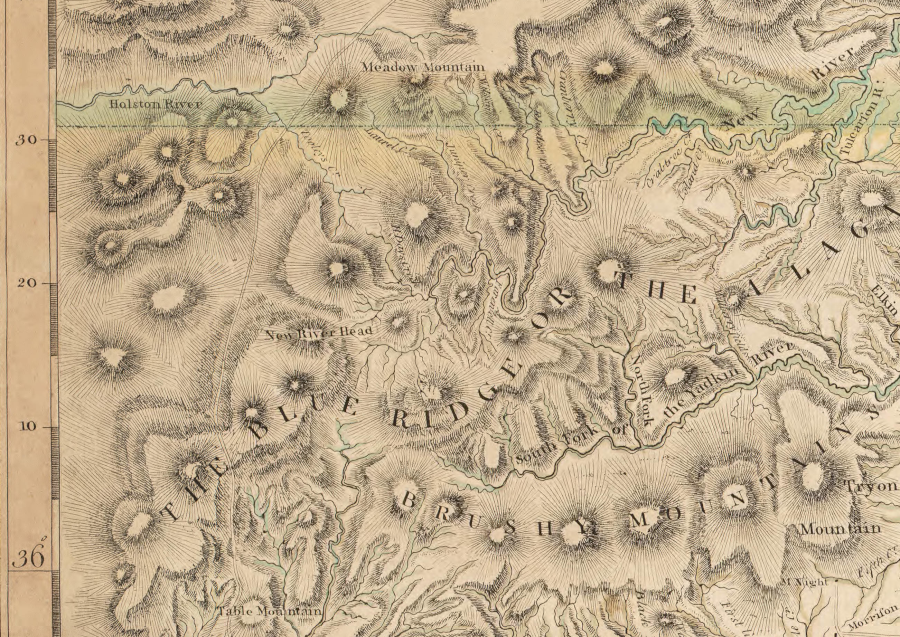

the exact location of the watershed divide separating the headwaters of the Roanoke River from the New River was poorly understood throughout the colonial era

(modern Blacksburg area marked by red X)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements by John Mitchell (1755)

Byrd was so impressed by the quality of the land along the border, he soon obtained a land grant from the proprietors in North Carolina. Byrd had William Mayo, one of the Virginia surveyors in 1728, mark the limits of his 20,000 acres where the Dan River crosses into Virginia. (Mayo also was one of the surveyors in 1736 for the Fairfax Grant, and Byrd was one of the colony's commissioners for that effort.)

Byrd's grant on Dan River

Source: William Byrd II, The Westover manuscripts: containing the history of the dividing line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina: A journey to the land of Eden, A.D. 1736: and A progress to the mines (p. 121)

when Edward Moseley produced his map in 1733, he showed William Byrd's grant but indicated it was located on the Fitzwilliam River, named after Virginia survey commissioner Richard Fitzwilliam

Source: Source: A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina by Edward Moseley, 1733

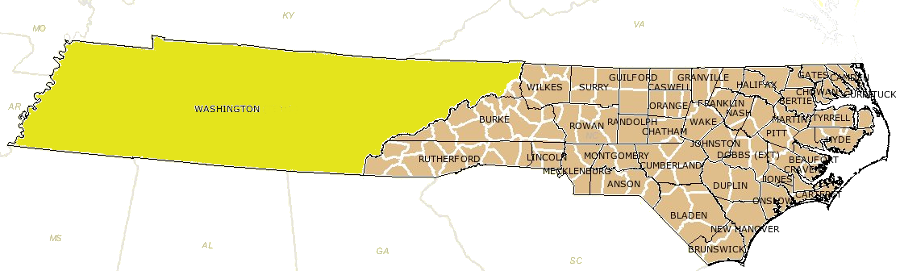

North Carolina officially became a royal colony in 1729. Heirs of seven of the eight proprietors who had received the original land grant from Charles II in 1663 sold their claims to the crown. The eigth heir, Lord Carteret retained his land adjacent to Virginia. That allowed him to allowing him to continue to collect quitrents and sell parcels in what was close to half of the North Carolina colony.

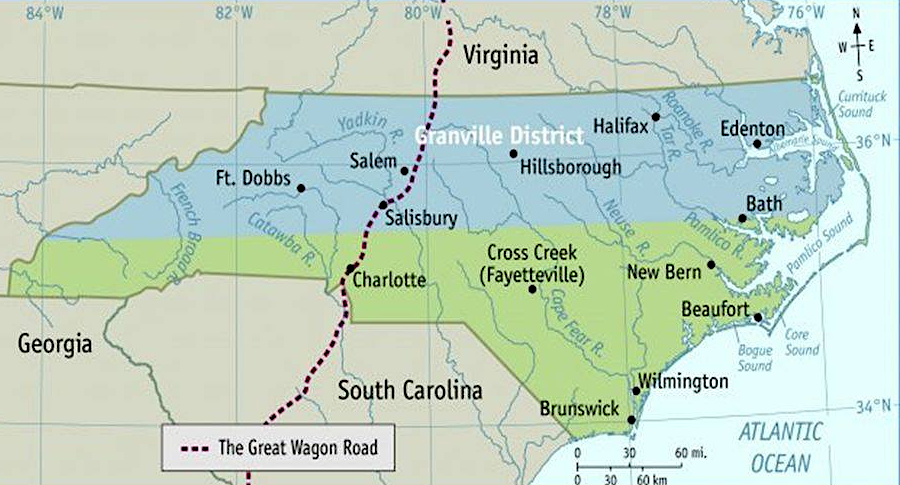

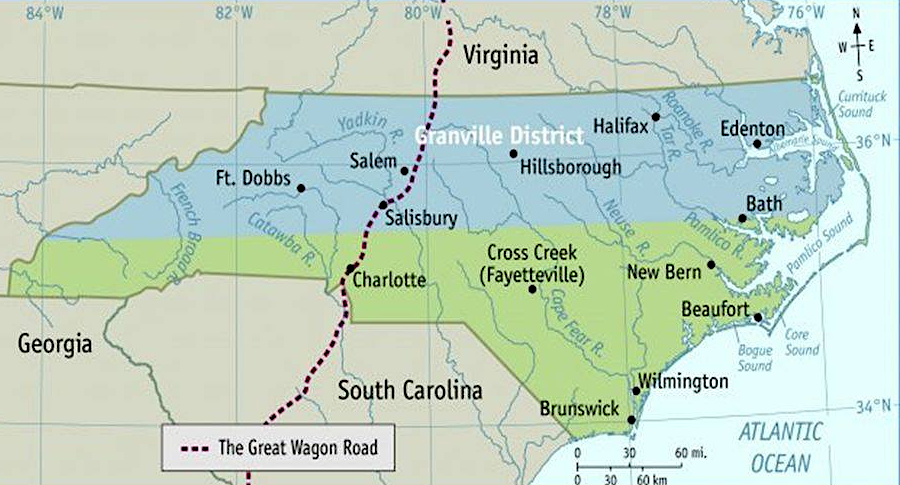

After Lord Carteret became Earl of Granville in 1744, his territory was known as the Granville District. Its northern boundary was defined by the 1728 survey.20

the Granville District was south of the Virginia-North Carolina boundary

Source: Fort Dobbs State Historic Site (Facebook post, February 1, 2019)

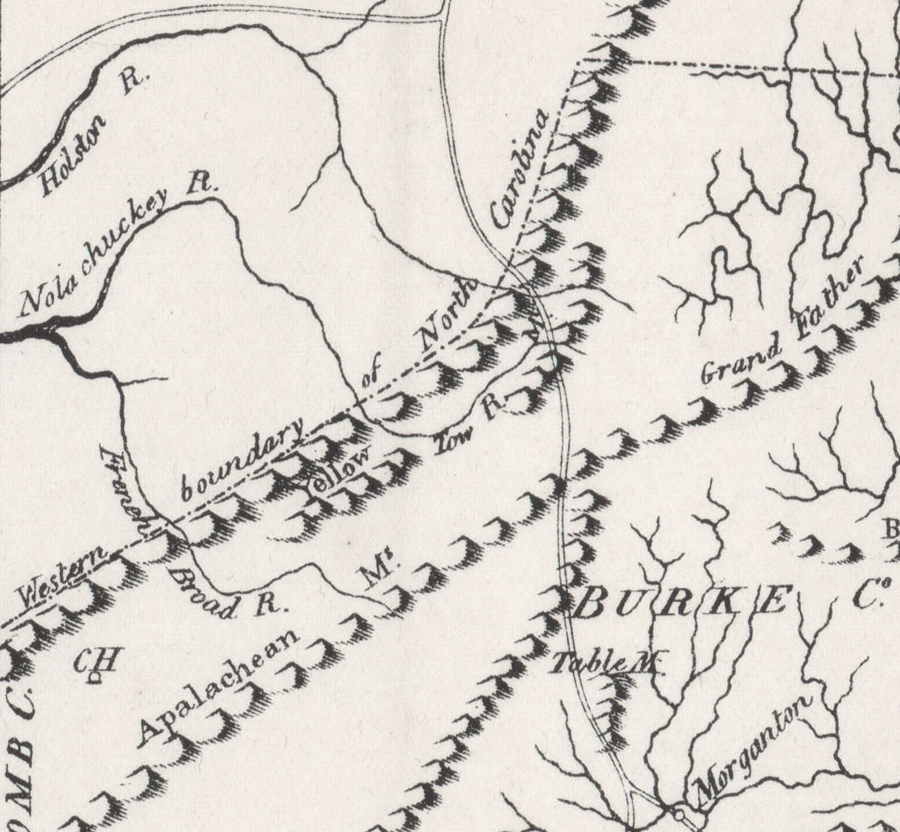

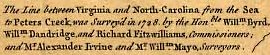

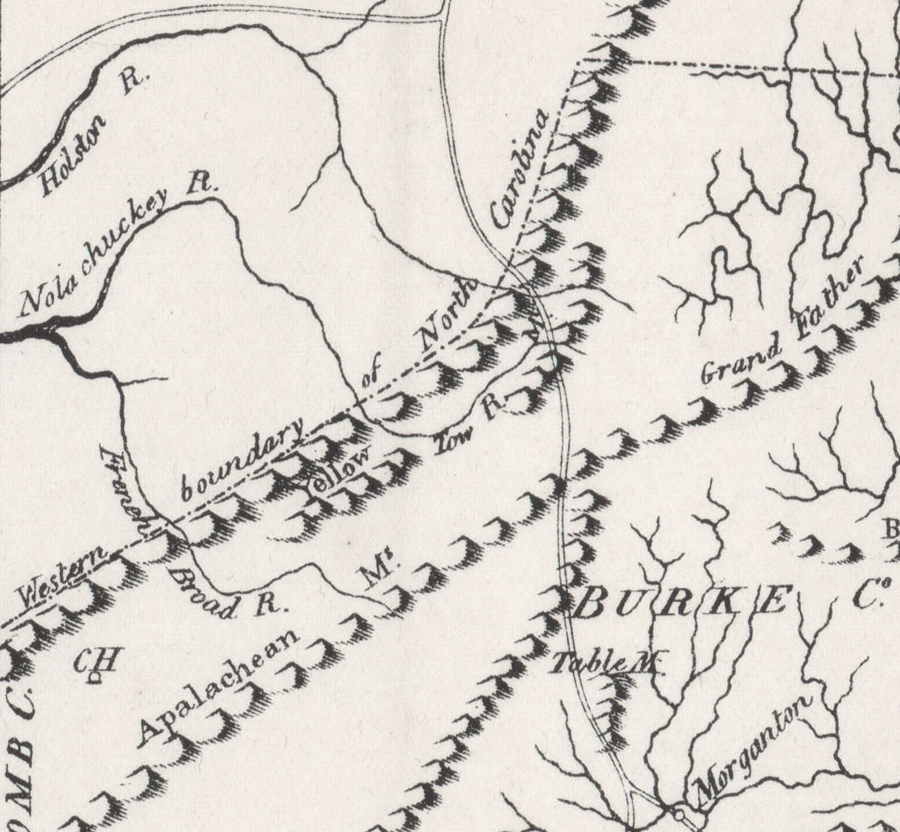

In 1749, a new survey extended the surveyed Virginia-North Carolina boundary 90 miles further to the west. Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson were Virginia's commissioners and surveyors, while North Carolina appointed William Churton and Daniel Weldon to represent that colony in defining the boundary in 1749.

At the time of that 1749 survey, Fry was the surveyor for Albemarle County and former professor of mathematics at William and Mary. He had been a commissioner for Virginia during the 1746 survey of the Fairfax Grant line between the headspring of the Rapidan River to the headspring of the Potomac River, the "back line" that cut straight through the Shenandoah Valley to mark the southwestern edge of Lord Fairfax's territory.

Jefferson was the former surveyor of Goochland County, and had completed the survey of the Northern Neck that defined the boundaries of Lord Fairfax's land. He ended up technically as Fry's assistant when Goochland County was divided and Albemarle County was created. The two operated as partners during the survey of the North Carolina-Virginia border, and later ensuring the production of several versions of a map of Virginia during the 1750's.21

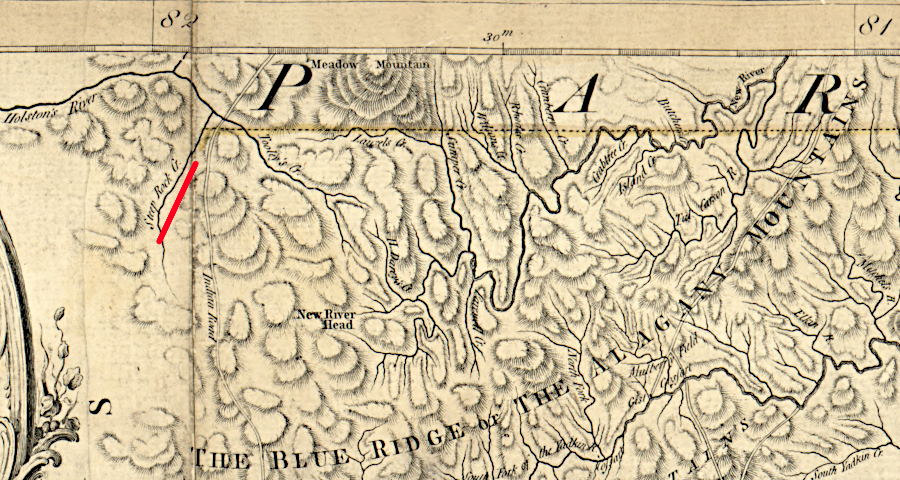

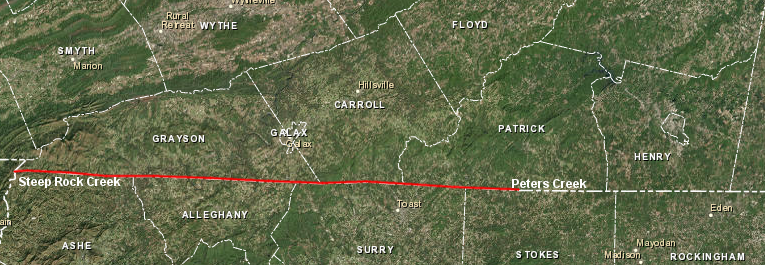

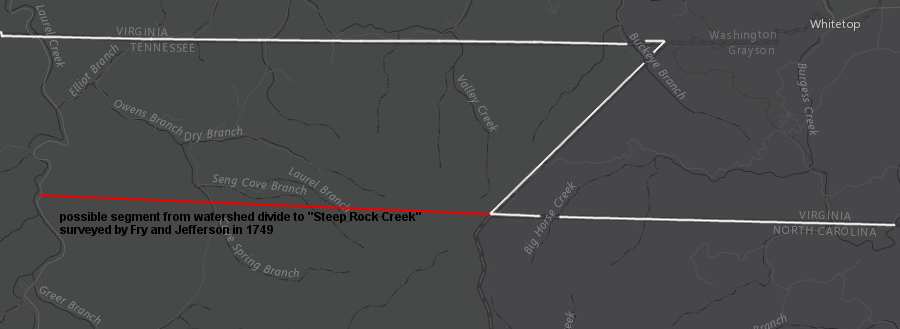

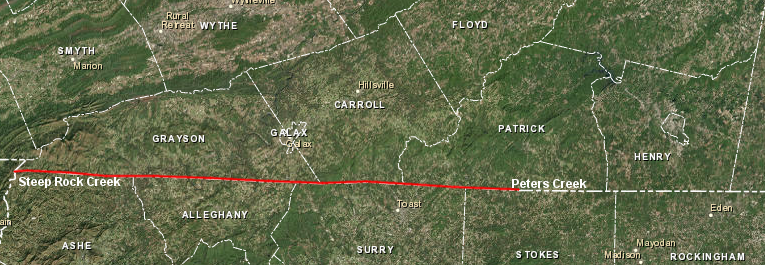

The four surveyors started where the survey of the "dividing line" had stopped 21 years earlier at Peters Creek. Their 1749 survey stopped after 90 miles at Steep Rock Creek, southeast of modern-day Damascus and about two miles from the Holston River.

the 1749 survey stopped at Steep Rock Creek

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina.

Steep Rock Creek was the defined end of the boundary survey

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North and South Carolina with their Indian frontiers (attributed to Henry Mouzon, 1775)

Finding the end point of that survey today is not simple. That point is not part of the current boundaries between Virginia, North Carolina, or Tennessee. The names of the small streams have changed over time; no "Steep Rock Creek" appears on modern maps or in the USGS Geographic Names Information System.

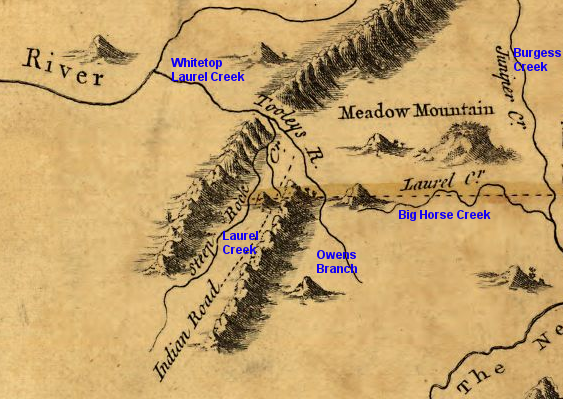

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson surveyed the Virginia-North Carolina border in 1749 from Peters Creek west to "Steep Rock Creek"

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

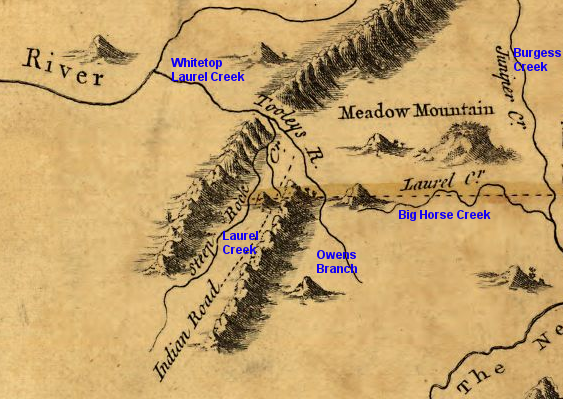

Steep Rock Creek on the Fry-Jefferson map may be the stream now called Laurel Creek, which is a tributary of the South Fork of the Holston River. In a letter sent to the governor of Virginia in 1787, Col. Arthur Campbell of Washington County included "a place called Steep Rock Creek, since known by the name of Laurel Fork of the Holston River."

If "Steep Rock Creek" is now the modern Laurel Creek, then the "Laurel Creek" on Fry and Jefferson's map of Virginia is apparently the stream now called Big Horse Creek. Laurel Creek on the map is shown as a tributary of the North Fork of the New River, and that would be consistent with Big Horse Creek today.

Steep Rock Creek is known as Laurel Creek in Tennessee today (blue indicates how modern stream names correlate to 1749 stream names)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina.

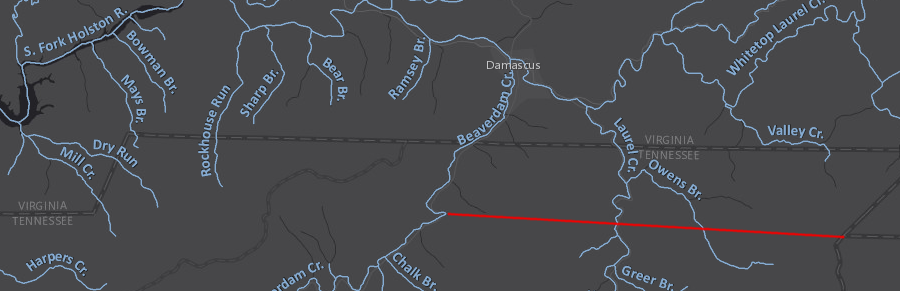

Regional historian Lewis Preston Summers suggested that the 1749 survey stopped at what today is known as Beaverdam Creek. If so, the end point may well be on a small island located just upstream of the Backbone Rock, a distinctive spur ridge of Holston Mountain that forces the creek to make a sharp bend. That site is now in Backbone Rock Recreation Area, a part of Cherokee National Forest.

However, Summers was inconsistent in his identification of the end point. Two pages earlier in the same publication he said:22

- The southern boundary of Virginia, extending from Steep Rock creek, now the Laurel Fork of the Holston River...

Lewis Preston Summers suggested a century ago that Steep Rock Creek could be modern-day Beaverdam Creek rather than Laurel Creek in Tennessee - if so, the 1749 survey would have followed the red line

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

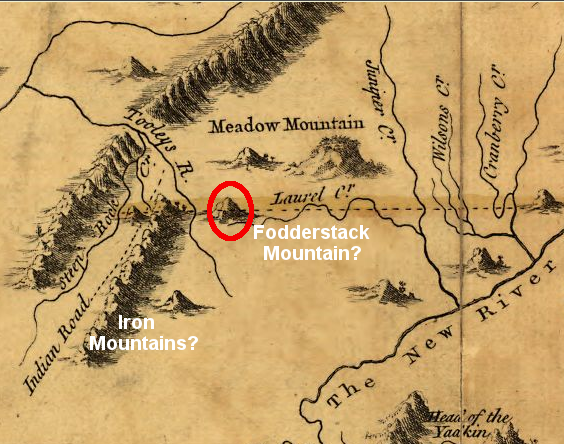

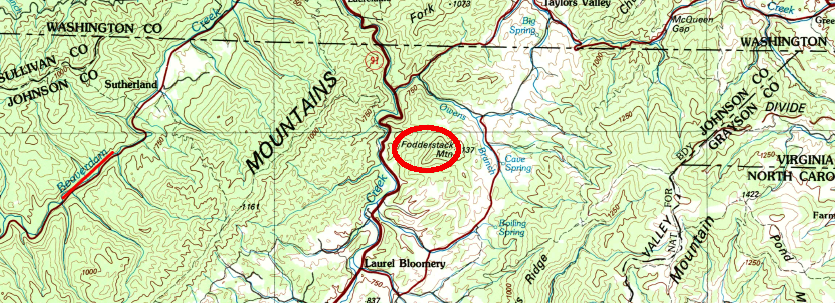

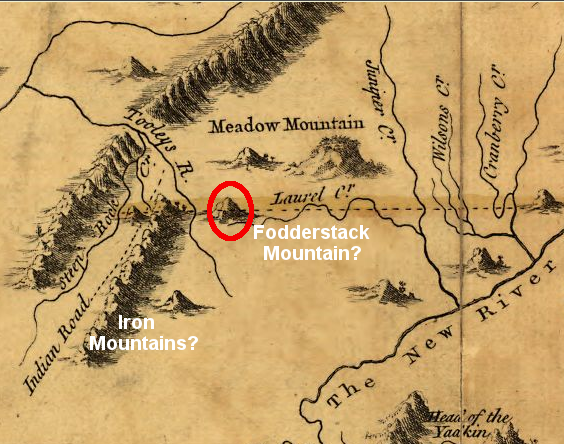

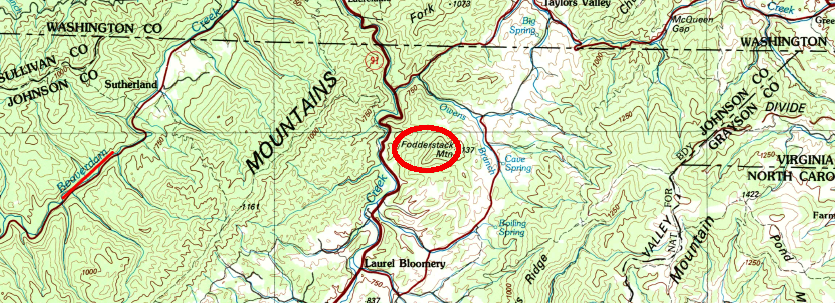

If Fry and Jefferson continued further west to Beaverdam Creek rather than stopped at Laurel Creek, then the mountains drawn on their map would correlate with modern Fodderstack Mountain and the Iron Mountains.

if the feature circled in red is modern Fodderstack Mountain, then the range to the west could be the modern Iron Mountains

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina.

the Fry-Jefferson survey could have ended on modern Beaverdam Creek rather than on modern Laurel Creek, if their survey map depicted Fodderstack Mountain and the modern Iron Mountains

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Wytheville 30x60 quad (1982)

Today the western corner of Virginia/North Carolina is located near the watershed divide which separates Big Horse Creek (which drains into the New River) and Valley Creek (which drains into the Holston and ultimately the Tennessee River).

the current Virginia-North Carolina boundary ends near the watershed divide between Valley Creek (in the Tennessee River watershed) and Big Horse Creek (in the New River watershed)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Today, the end of the Virginia-North Carolina border stops at a point east of both Laurel Creek and Beaverdam Creek. Assuming one of those creeks was the stream that Fry and Jefferson labeled as "Steep Rock Creek," then the far western tip of their 1749 survey does not define the modern boundary.

the modern Virginia-North Carolina border does not include the very last part of the Fry and Jefferson survey, ending at Steep Rock Creek (indicated here as modern Laurel Creek, rather than Beaverdam Creek further west)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Why was a boundary survey justified in 1749? British officials in London wanted a better understanding of the shrinking gap between the colonies and French exploration in the Ohio River valley, but the internal-to-the-colony justification for a survey was land speculation and population growth in southwestern Virginia.

The General Assembly chose to fund a 1749 survey of the southern boundary, rather than an exploration of the Ohio River and lands to the west. Virginia officials were deeply involved in establishing colonial control of what today is northern Tennessee, through treaties and warfare with Native American tribes, through negotiations and ultimately warfare with British officials, and through negotiated land cessions and lawsuits with fellow states in the newly-created United States of America.

In 1745 Virginia colonial officials gave the Greenbrier Company a 100,000 acre land grant in the valley of the Greenbrier River. The Ohio Company organized in 1747 to speculate in lands near the Forks of the Ohio, beyond the western edge of the Fairfax Grant. In 1749 that Ohio Company received a grant from the Governor's Council for up to 500,000 acres. It helped that the president of the Council (Thomas Lee) and the governor (Lord Dinwiddie) were both members of the Ohio Company and would gain person profits from their governmental actions; conflicts of interest regarding public office and private benefit were common in the colonial era.

In the same year, the Loyal Land Company obtained a grant for 800,000 acres. To avoid conflict with the Greenbrier Company and the Ohio Company, the Loyal Land Company focused its land speculation in the trans-Allegheny territory south of the Ohio River, and away from the valley of the Greenbrier River.

The Ohio Company had to recruit 100 people to move onto its lands within seven years. That company negotiated a peace treaty with the Iroquois and Shawnee at Loggstown in 1752 to facilitate settlement in the Ohio River valley. The Loyal Land Company had to submit surveys within four years to gain title to land, but settlement was not mandated and the company negotiated no separate treaties with Iroquois, Shawnee, or Cherokee.

Clarifying the Virginia-North Carolina boundary was more important to the Loyal Land Company. Its 800,000 acre grant triggered the 1749 boundary survey, because the surveyed land must be located north of Virginia's southern boundary:23

- Leave is given them to take up and survey Eight Hundred Thousand Acres of Land in one or more Surveys, beginning on the Bounds between this Colony and North Carolina, and running to the Westward and to the North so as to include the said Quantity, and they are allowed four Years Time to survey and pay Rights for the same, upon Return of the Plans to the Secretary's Office.

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson were both members of the Loyal Land Company. Their work with the North Carolina surveyors was to the benefit of the colonial governments, but defining the boundary was also a key part of the Loyal Land Company's efforts to make a profit by selling land.

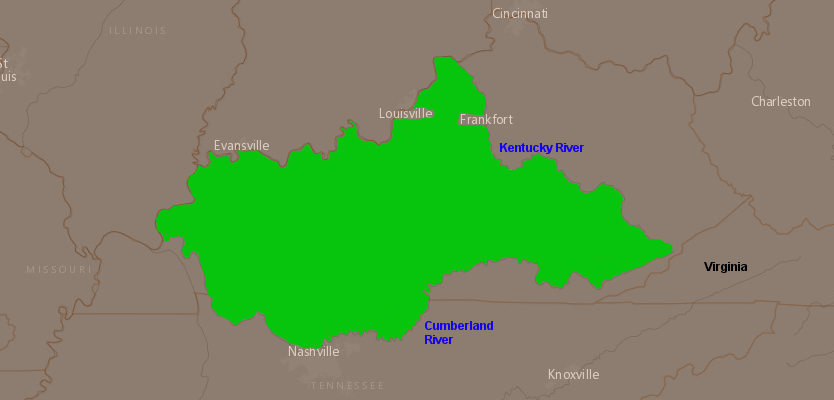

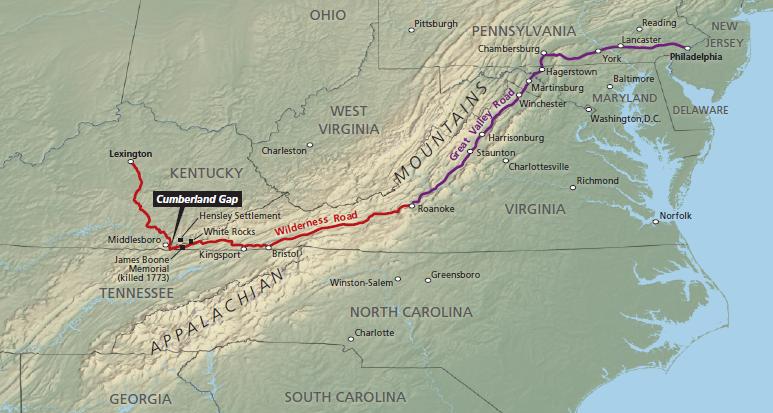

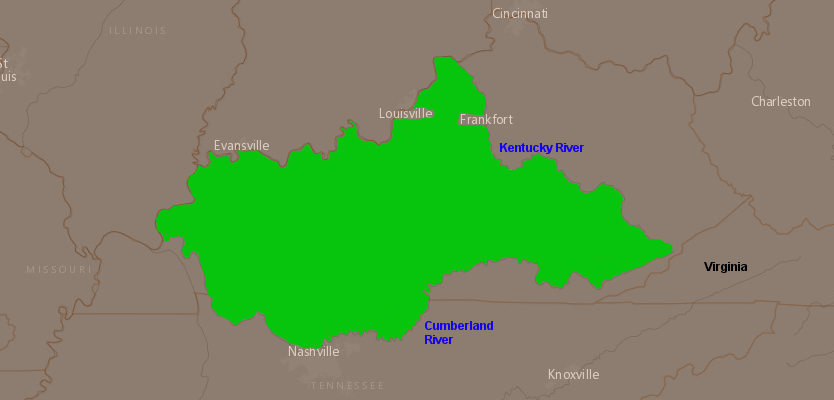

Thomas Walker, another leading member of the company, explored southwestern Virginia in 1750 beyond the point where the 1749 survey stopped. Walker traveled through Cumberland Gap and identified the high potential for surveying and selling parcels in the Kentucky region.

after passing through Cumberland Gap (white X) in 1750, Thomas Walker discovered the Loyal Land Company would be able to find rich, level bottomland north of the 36° 30' line of latitude (red line)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The French and Indian War temporarily limited demand for purchasing lands from any of the land companies with claims in the trans-Allegheny region. The French were decisively defeated in North America by 1760, but conflict with Native Americans continued for several more years.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the Seven Years War/French and Indian War and defined a new western edge for Virginia. Prior to that treaty, London officials had not formally blocked Virginia's claim under the Second Charter of 1609 that the colony extended across the continent to the Pacific Ocean.

British officials had altered Virginia's boundaries on the north and south. Since the 1609 charter, the extent of the colony of Virginia had been limited on the north to the 40° line of latitude by the charter for New England (at least west of the Illinois River), and on the south to the 36° 30' line of latitude by the 1665 grant to the proprietors of North Carolina.

Until 1763 there was no boundary on the western edge of the Virginia colony until reaching the "Southern seas" (Pacific Ocean) - assuming one accepted that in 1609 James I had the authority to determine land ownership in perpetuity on that portion of the North American continent. Obviously the French, Spanish, and Native American tribes were not inclined to agree, but British officials allowed that claim to stand for 154 years until the end of the Seven Years War (known in North America as the French and Indian War).

In the 1763 treaty, France agreed to transfer its land claims west of the Mississippi River to Spain. England recognized Spanish authority over the Louisiana Territory, and the Mississippi River became the new western border of Virginia.

Virginia's tenuous claim to lands west of the Mississippi River (shown here in John Mitchell's 1755 map) were abandoned by English officials who negotiated the Treaty of Paris in 1763

Source: Library of Congress, John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

Virginia officials did not protest that cession of their western land claim extending to the "Southern seas" because lands west of the Mississippi River had little value to Virginia-based land speculators. The colonial population was still too low to create demand for that territory. It was too far away, and already occupied in part by Spanish and French settlers as well as Native Americans.

In contrast, Virginia officials vigorously opposed the Proclamation of 1763. The limit on western expansion by that royal decision had a quick impact on land speculators in Williamsburg and in plantation houses east of the Blue Ridge.

In the Proclamation of 1763, King George III prohibited settlement across the watershed divides that separated rivers flowing into the Atlantic Ocean from the Ohio, New, and Tennessee rivers:24

- no Governor or Commander in Chief in any of our other Colonies or Plantations in America [...may] grant Warrants of Survey, or pass Patents for any Lands beyond the Heads or Sources of any of the Rivers which fall into the Atlantic Ocean from the West and North West...

The proclamation was intended to stop colonial settlement in most of the Ohio River watershed. Officials in London hoped that blocking migration to the west of the proclamation line would reduce the number of hostile Native American-settler interactions, minimizing the cost of maintaining peace in North America after the French and Indian War. If it had been implemented as envisioned in London, there would have been no need to define the Virginia-North Carolina colonial boundary west of Steep Rock Creek.

The Proclamation of 1763 blocked colonial dreams of military success against France being followed by greater access to western lands. It took colonial leaders, including some appointed by the king, several years to find ways around the ban on settling in the Mississippi River watershed.

Several treaties finally modified the ban and authorized settlement, but the proclamation delayed the ability of settlers to obtain legal title to lands along the Virginia-Carolina border and constrained the profits of the speculators. The Loyal Land Company needed surveys so parcels could be sold as the population moved west, but King George blocked their efforts in 1763.

the northern border of North Carolina-Virginia was left undefined for 30 years after the Fry and Jefferson stopped at Steep Rock Creek - and full implementation of the Proclamation Line of 1763 would have eliminated any need to extend it further

Source: Library of Congress, A new and accurate map of North Carolina in North America (1779)

The land speculators in the Ohio Company, Greenbrier Company, and Loyal Land Company were politically-powerful members of the gentry who ensured that colonial officials did not support the proclamation. On the frontier itself, some settlers had already carved out farms in some areas such as Sapling Grove (modern-day Bristol) that became off-limits according to the Proclamation Line of 1763.

After obtaining their grant, members of the Loyal Land Company were particularly interested in clarifying the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. The 1749 survey stopped at the Blue Ridge, but the company expected to make its profits from lands further to the west. As the speculators achieved their goal of overcoming the limits in the Proclamation of 1763 through new treaties with Native American tribes in 1768 and 1770, pushing the boundary further west became of greater interest.

John Collet's 1770 map of North Carolina simply extended the 1749 boundary westward in a straight line

Source: University of North Carolina, A Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey by John Collet (1770)

Settlers who actually lived on the border may have been less interested in the exact location of boundary lines adopted by officials in Williamsburg or London. Many of the earliest frontier settlers were willing to build simple shelters, plant crops, and raise families without filing official surveys at a county courthouse and purchasing legal ownership. "Corn rights" (planting corn, or marking trees with a blaze using a hatchet) established a claim. If someone like a representative of the Loyal Land Company demanded that a squatter pay for use of the land, then at least the squatter had been able to select the best site in the area. Otherwise, court filings cost money and formal land purchases could trigger collection of taxes.

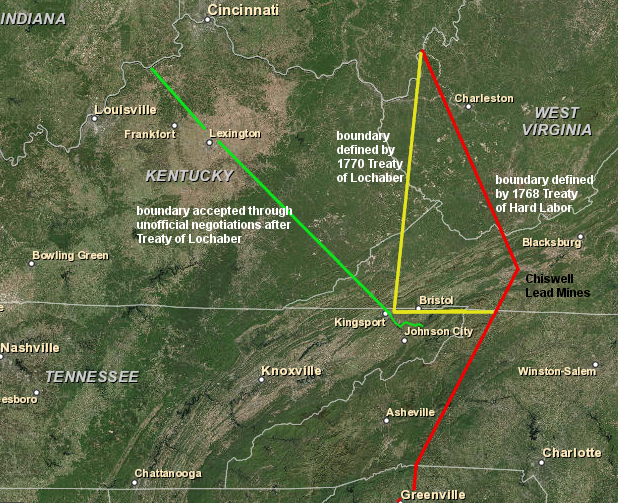

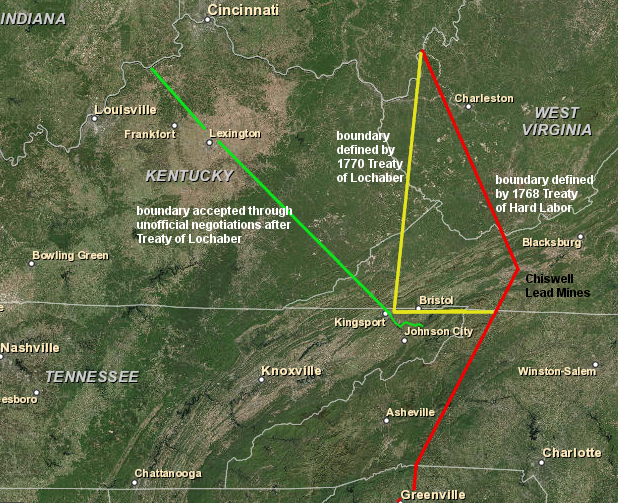

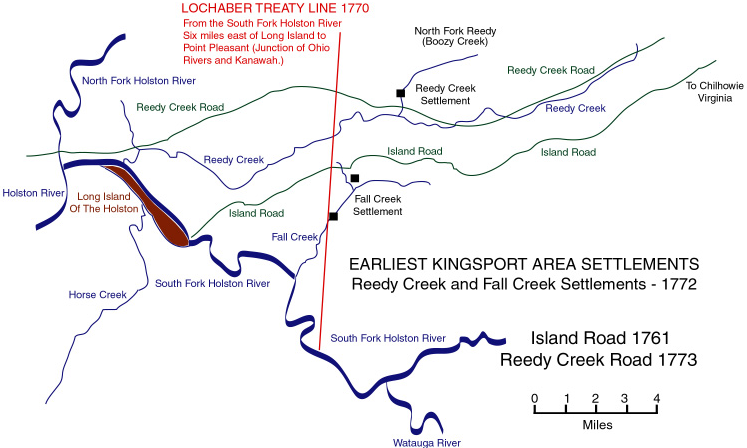

In 1768 the western limits of authorized settlement were extended through the Treaty of Hard Labor with the Cherokee, and then again two years later with the Cherokee in the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber.

The Treaty of Hard Labor defined a new boundary north from the South Carolina border to a site in the Blue Ridge (later named Mount Tryon after the North Carolina governor), then northeast in a straight line to the lead mines of John Chiswell near modern-day Wytheville on I-81, and finally in a straight line northwest to the mouth of the Kanawha River. Existing settlements on the New River, including Ingles Ferry and Dunkard Bottom near modern-day Radford, were placed on the Virginia side of the boundary.

the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor defined the edge of colonial settlement vs. the Cherokee Hunting Grounds, by drawing a line north from a site near South Carolina to Chiswell's Mine and then directly to the mouth of the Kanawha River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the country between Albemarle Sound, and Lake Erie, comprehending the whole of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and Pensylvania, with parts of several other of the United States of America (1787)

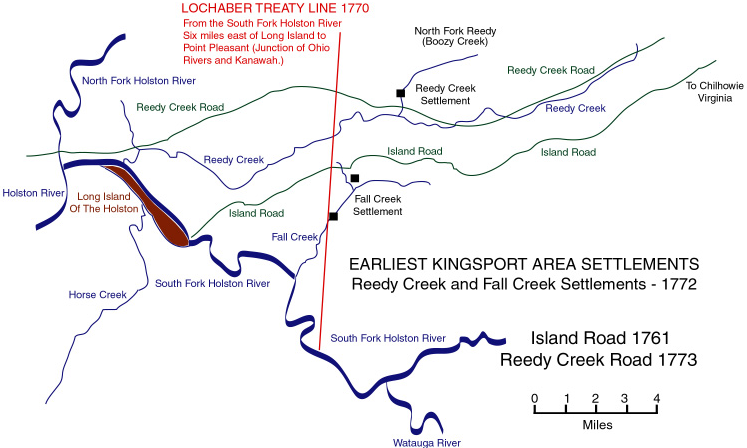

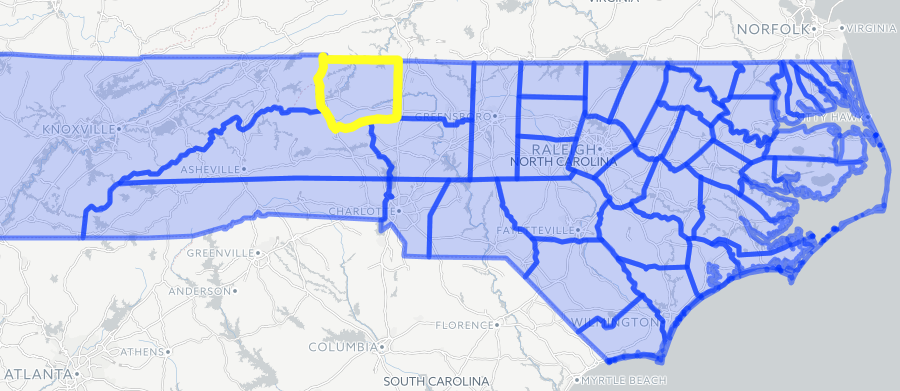

The 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor did not legitimize the settlers already living southwest of the line on the Holston River. Two years later, that problem was solved for some of the colonists by the official Treaty of Lochaber in 1770. It drew a line westward from the Blue Ridge at the 36° 30' line of latitude to a point on the Holston River, stopping six miles upstream (east) of the Long Island of the Holston, and then went north to the mouth of the Kanawha River.

the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber authorized settlement on lands that were north of the Virginia-North Carolina boundary (extended to Holston River) and east of a line between the Holston River to the mouth of the Kanawha River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina

There were unofficial negotiations by colonial officials with the Cherokees after concurring with the Treaty of Lochaber, reportedly after generous distribution of rum. The unofficial deal expanding the territory relinquished by the Cherokee was endorsed by colonial officials, but not the official negotiator appointed by the Board of Trade in London.

That post-treaty deal moved the northern boundary on the Ohio River downstream from the mouth of the Kanawha River to the mouth of the Kentucky River, a shift of over 150 miles further west. The change substantially increased the acreage surrendered by the Cherokee, and increased the lands available for Virginia speculators such as the Loyal Land Company to survey and patent - but clear title to that land was not achieved by negotiating with just the Iroquois and Cherokee.25

treaties in 1768 and 1770 expanded the territory controlled by Virginia, while reducing the extent of the Cherokee Hunting Grounds

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix had extinguished whatever claims the Iroquois made to the land south of the Ohio River and west to the Tennessee River. The 1768 and 1770 treaties with the Cherokee addressed that group's claims to much of the same land south of the Ohio River. However, the treaties did not consider claims to those same lands by other Native Americans such as the Shawnee.

Their major towns were located north of the Ohio River but who claimed rights to much of the territory on the south side. Shawnee claims eastward to the Virginia settlements in the Shenandoah Valley were demonstrated by raids during the French and Indian War, including the seizure of Mary Draper Ingles on the New River near modern-day Blacksburg.

North Carolina made no effort to establish a local government in the territory that had been ceded by the Cherokee under the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor because all of that territory was believed to be within the boundaries of Virginia. The 1770 Treaty of Lochaber extended the dividing line between the colonists and Cherokee westward to the Holston River, extending the 1749 boundary by following what was believed to be the 36° 30' line of latitude.

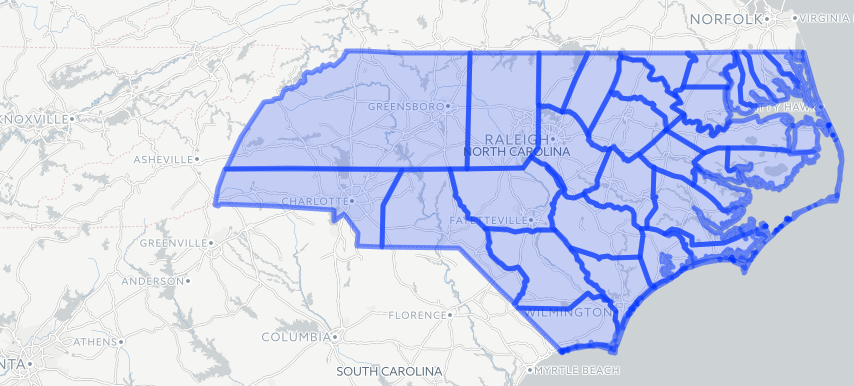

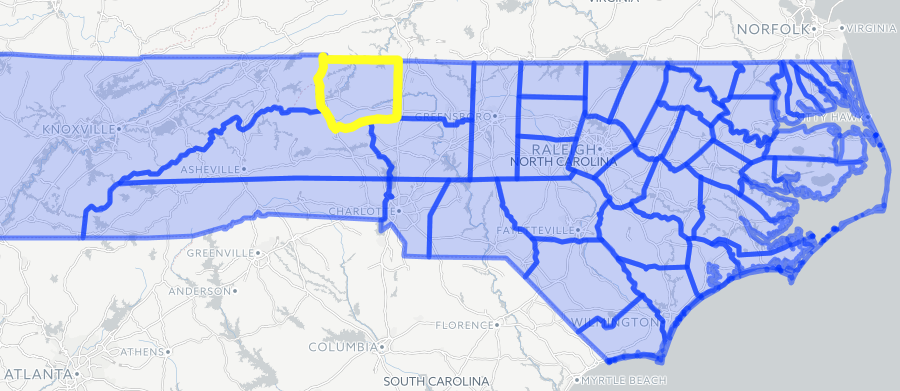

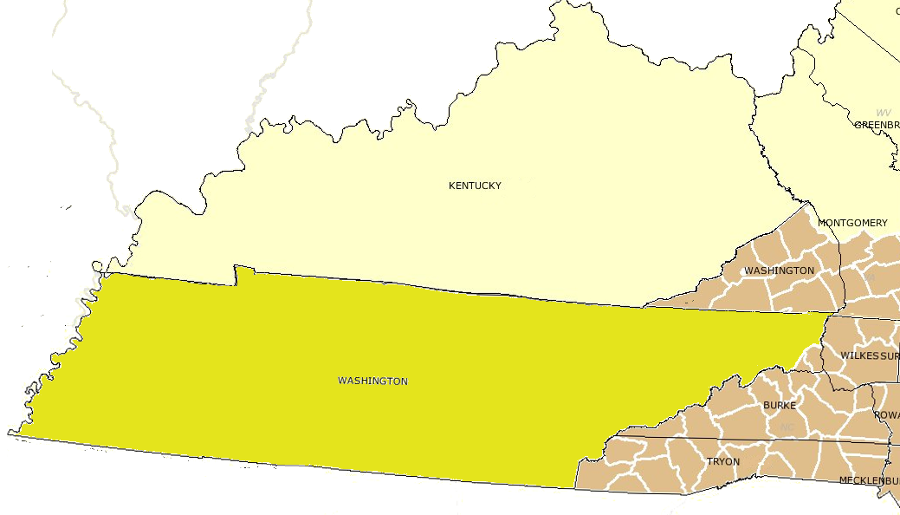

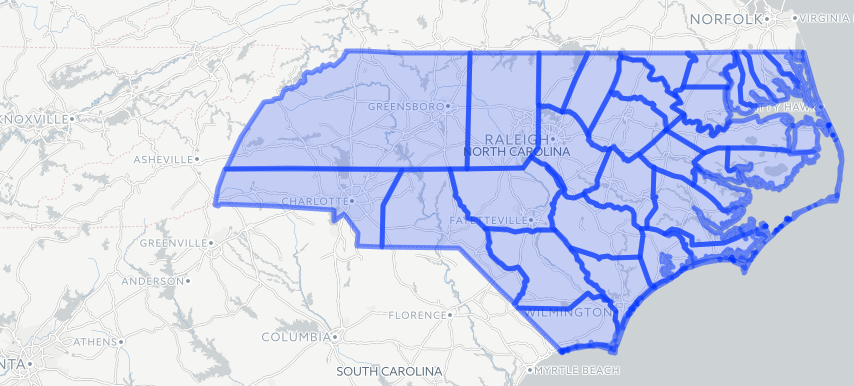

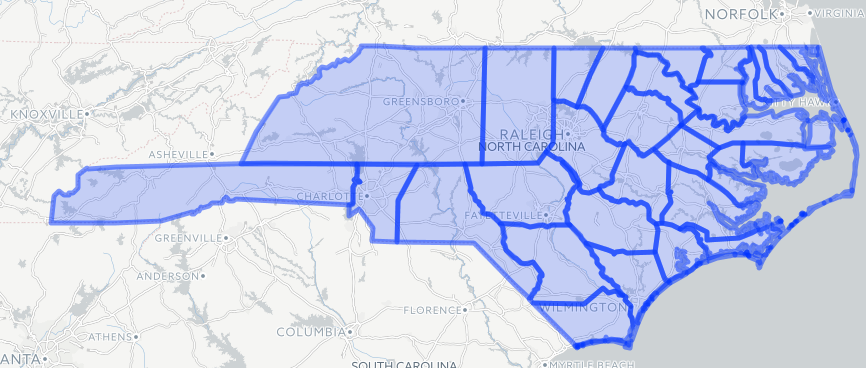

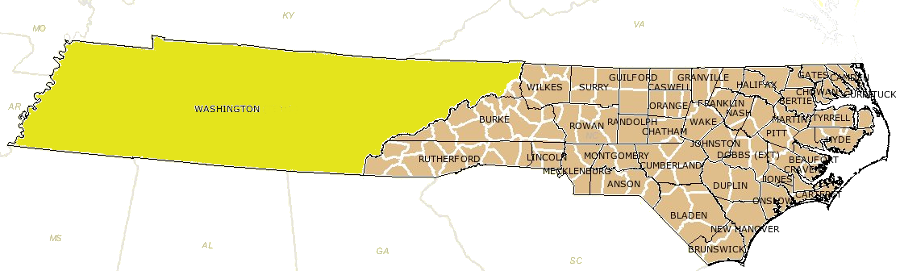

in 1767, North Carolina had organized no counties west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

in 1769, newly-created Tryon County asserted North Carolina's claims to territory near South Carolina/Georgia

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

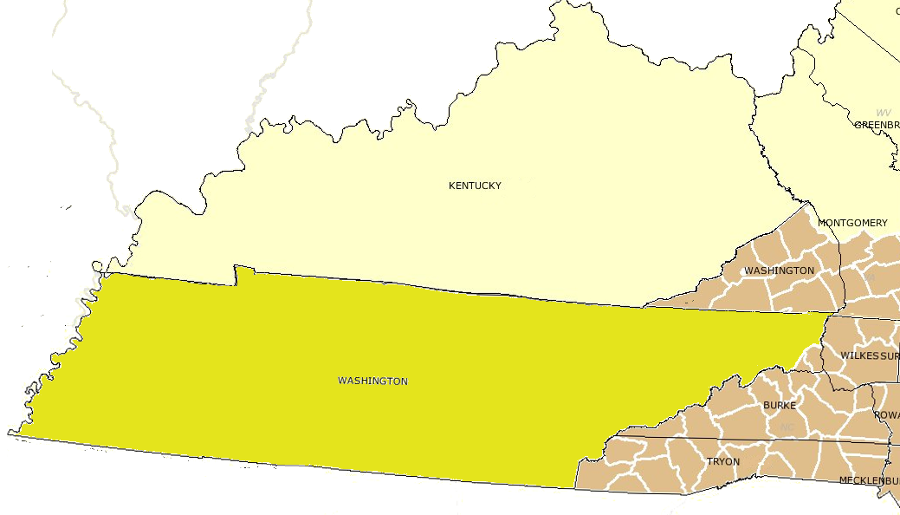

North Carolina organized the Washington District in 1776, and made it a county in 1777

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

creation of Wilkes County in 1778 defined a final North Carolina-Virginia border

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Land north of the Holston River, in the area authorized by the Treaty of Lochaber, was considered to be part of Virginia. The survey of the new dividing line separating Cherokee lands and Virginia, as defined in the 1770 treaty, was the responsibility of Virginia. Marking the boundary defined by the Treaty of Lochaber was not a joint boundary survey done by Virginia together with the colony of North Carolina.

Thomas Jefferson indicated the southern boundary of Washington County, Virginia extended to the spot on the Holston River six miles east of Long Island as defined in the Treaty of Lochaber, before going due north towards the mouth of the Kanawha River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the country between Albemarle Sound, and Lake Erie, comprehending the whole of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and Pensylvania, with parts of several other of the United States of America (1787)

John Donelson was tasked to mark the edge of Cherokee-Virginia territory. He was the surveyor for Pittsylvania County and a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. Like so many other surveyors and commissioners overseeing surveys on frontier lands, including William Byrd II and George Washington, Donelson gained a unique understanding of the area and became a land speculator on the frontier. (His daughter later Rachel married Andrew Jackson, but died before Jackson was elected president.)

The 1771 Donelson Line extended the 1749 boundary line of Fry, Jefferson and their North Carolina counterparts westward to the Holston River. That section of the Donelson Line was treated as the Virginia-North Carolina boundary, and as the southern edge of Botetourt County.

In 1772 Virginia subdivided Botetourt County and created Fincastle County. Creating that new county meant residents living on the Holston River north of the Donelson Line were obliged (at least in theory) to pay taxes for local services and to serve in the Fincastle County militia.

In return, settlers at the far southwestern edge of Virginia could now file surveys and resolve disputes over land titles at a county seat located much closer. The Fincastle county seat was placed at the lead mines owned by Col. John Chiswell on the New River (later known as Austinville), much closer than the old Botetourt county seat on the James River.26

The 1771 survey revealed that Holston River settlements at Reedy Creek were north of Donelson's Line, but Watauga (now Elizabethton, TN), Nolichucky (now Erwin, TN), and Carter's Valley (between Rogersville and Kingsport, TN) were clearly south of the Treaty of Lochaber boundary. Those settlements were south of the Virginia boundary as defined by Donelson, and encroached on lands reserved for the Cherokee. The settlements were also located west of all organized county governments in North Carolina that provided land recordation services and official militia protection.

Donelson's Line marking the boundaries defined in the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber went east-west from the end of the Fry-Jefferson survey to the Holston River, then north to the mouth of the Kanawha River

Source: Discover Kingsport, Maps: Kingsport

Rather than move "back into Virginia," the families living on the wrong side of the line concentrated at one place, Watauga, and successfully negotiated with the Cherokee to lease land at that site. The beyond-the-Donelson-Line residents formed the Watauga Association as their local government, separate from both North Carolina and Virginia.

By 1775, a set of speculators led by Colonel Richard Henderson sought to take advantage of the circumstances. The speculators organized as the Transylvania Company and tried to bypass the Virginia government in Williamsburg. The company purchased 20 million acres west of the Kentucky River, which was the edge of settlement permitted by the Cherokee after informal arrangements following the Treaty of Lochaber negotiations.

The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals between the Transylvania Company and the Cherokees involved the 20 million acres between the Kentucky and Cumberland rivers. The deal was clearly inconsistent with the prohibition of private purchases in the Proclamation of 1763. Choosing the Kentucky River as the eastern edge of the Transylvania purchase allowed the Transylvania Company to avoid conflicts with settlers who purchased land after the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor, the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, and post-treaty negotiations moving the line of authorized settlement westward to the Kentucky River.

the primary Transylvania Company purchase was located between the Kentucky and Cumberland Rivers - and most of that territory was already claimed by Virginia under its Second Charter in 1609

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Cherokee demonstrated in the 1760's and 1770's that they were willing to abandon lands on their northern edge, the territory in modern-day Kentucky and West Virginia. The plan of the Cherokee chiefs was to move further south, concentrating in settlements on the western edge of South Carolina/Georgia. That area was closer to the rival Creek and Choctaw - but if the colonists chose to migrate into the lands above the Cumberland River, they would stay north of the new Cherokee homeland and conflicts might be minimized.

The Cherokee logic was consistent with the English logic behind the Proclamation of 1763. Separating the Native Americans from the settlers to avoid disputes would be cheaper than war.

The decision to abandon core traditional territory on the Holston River, especially the sale of Long Island to the Transylvania Company, created major conflict within the Cherokee community. A group of Cherokee led by Dragging Canoe opposed the sale. After the leading chiefs agreed to the sale of northern lands the Transylvania Company, Dragging Canoe formed a splinter group that organized attacks on the Watauga settlements and later allied with the British during the American Revolution.

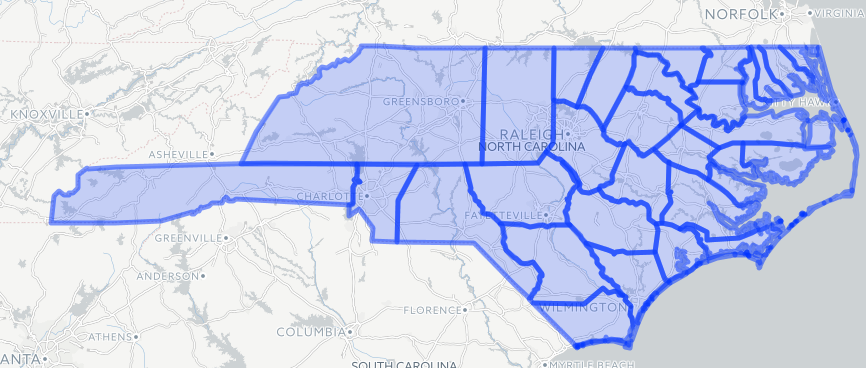

Both Virginia and North Carolina militia responded to Dragging Canoe's attacks, marching to the Holston River and joining in retaliatory raids on Cherokee towns. The Watauga settlers had already petitioned North Carolina to annex them and establish a local government within that state. North Carolina created the Washington District in 1776 and then organized Washington County in 1777, with boundaries extending to the Mississippi River.

the new North Carolina state government created Washington District in 1776 and organized it into Washington County in 1777, to govern the land west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries (showing county boundaries in 1777)

A western extension of the Donelson Line and Fry-Jefferson line along the 36° 30' line of latitude was the presumed North Carolina-Virginia boundary in 1777. The boundary, now between states rather than colonies, was stretched west to the Mississippi River but remained unmarked beyond the point where Donelson had stopped in 1771 on the Holston River.

surveyors in the mountains were tasked to mark the Virginia-North Carolina boundary, based on the 36 degrees 30 minutes line of latitude

Source: University of North Carolina, A Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey (by John Collet, 1770)

Virginia provided more local government as well in 1777. The eastern gentry in Williamsburg, as well as settlers on the frontier, maneuvered to be certain that Virginia could issue reliable title to lands when approving surveys and patents to those land companies. The gentry was also speculating in land bounties that had been authorized in the Proclamation of 1763 for veterans of the French and Indian War. The bounties were of particular interest to George Washington, who was one of the gentry anticipating how those grants would be claimed.27

North Carolina assumed the Holston River settlements were in Virginia

Source: Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, North Carolina 1796

The Virginia legislature dissolved Fincastle County in 1776. Lord Dunmore, the last governor of Virginia appointed by the King of England, was a Scottish lord, the Viscount of Fincastle; his son was also named Fincastle. By 1776 rebellious Virginia leaders had forced Dunmore out of office and then eliminated the county whose name had honored Lord Dunmore. (The Botetourt County seat is still called Fincastle, however...)

In 1777 three new local jurisdictions, Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky counties, replaced Fincastle County. The Holston River settlers were now in Washington County, and could go to the county court at Abingdon to officially establish title to land parcels and resolve legal disputes.28

the Transylvania Company spurred Virginia and North Carolina to create new counties west of the Blue Ridge in 1777

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries (showing county boundaries in 1778)

The Transylvania Company threatened Virginia's claim to territory west of the official boundary defined by the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, starting in 1775. The Transylvania Company hired explorers and surveyors to document their purchase and initiate land sales. Daniel Boone, employed by the company, identified the path for the Wilderness Road from the Holston River through Cumberland Gap.

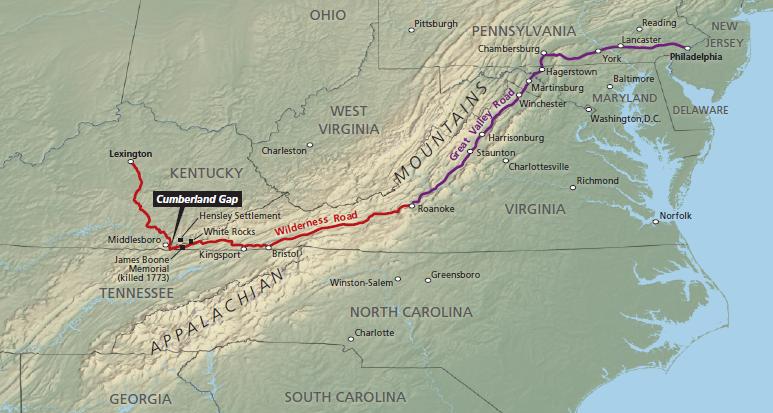

demand for legal land sales and purchases was the stimulus for surveying boundaries and extending the transportation network through southwestern Virginia

Source: National Park Service, Early American Frontier

Virginia and North Carolina officials refused to concede that the Transylvania Company had authority over the land purchased from the Cherokee at the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. The two states (no longer "colonies" after 1776) maintained their ownership and agreed to survey their shared state boundary to extend the line, going further west of where Fry and Jefferson had stopped in 1749 and Donelson had stopped in 1771.

A mutually-adopted boundary would help each new state assert its claims in the US Congress to land in the Tennessee River watershed. Blocking the Transylvania Company would allow both Virginia and North Carolina to obtain one-time revenue from sale of public land to settlers, and to direct annual taxes from settlers to state-defined county governments.

Complicating the challenge of establishing authority and ownership of western land, the Transylvania Company purchase occurred at the start of the American Revolution. Government operations were severely disrupted by the decision to declare independence and replace the colonial House of Burgesses with a new legislative structure (General Assembly) and to separate the executive, legislative, and judicial responsibilities for the first time in the history of Virginia.

Military failures created even more chaos. In May, 1779, Virginia experienced its first major invasion by the British. Sir George Collier sailed a fleet into the Chesapeake Bay and, with troops led by General Edward Mathew, seized Portsmouth. The British burned the Gosport Navy Yard and raided throughout Hampton Roads.

Nonetheless, in 1779 Virginia officials still found time to organize a survey with North Carolina to define the boundary line west of the Blue Ridge. The decision to launch a new survey when resources for defense were severely limited is a clue to the desire of top leaders in Virginia to facilitate speculation in western lands.

the simple solution for mapmakers after 1749 was to project the Virginia-North Carolina boundary west to the Mississippi River

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the western parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina (1778)

The Virginia survey team included Col. Thomas Walker. He was a member of the Loyal Land Company, and would lose a substantial amount of prime land if the Transylvania Company claim was upheld. Col. Richard Henderson was an official commissioner of the North Carolina survey team, and of course might benefit if the survey project was not completed. Conflicts of interest were common when frontier land was involved...

The survey process required judgment calls using a magnetic compass to determine direction and using a sextant aligned with the sun to determine latitude. If the survey line ran further north than the desired 36° 30' line, too much land would end up in North Carolina. If the line was located south of the 36° 30' latitude line, then Virginia would be enlarged at the expense of North Carolina.

At the start, the surveyors assessed each other's equipment, agreed on what variances would be appropriate for the magnetic compasses used by different surveyors, and concurred that Steep Rock Creek was 329 miles west of Currituck Inlet.

As the surveyors approached the Holston River, the North Carolinians and Virginians disagreed on the accuracy of the line. The North Carolina surveyors feared that if that line was extended west to the Cumberland River, the settlement at French Lick (now Nashville) would end up being located in Virginia.

Less than two weeks after starting the survey in early September, 1779, one of the Virginia commissioners reported that:29

- ...the Carolina Gentlemen had conceived an Opinion we were too far to the south of the true L[ine]

The two survey teams split up. The North Carolina surveyors angled to the north; the Virginians defined a different boundary line further to the south. They created the Walker and Henderson lines, named after the leaders of the teams from the two states. The dispute over which line marked the state boundaries created confusion regarding the status of a slice of land two miles wide through the Holston River watershed.

The conflict was not resolved with North Carolina. That state never agreed on a boundary line west of the point where Fry and Jefferson had stopped in 1749. Instead, North Carolina abandoned its efforts to govern the territory west of the Blue Ridge and ceded its land claims to the US Congress.

The first cession involved a corrupt arrangement, with members of the North Carolina legislature obtaining massive land grants and then ceding the land contingent upon Congress guaranteeing their private claims. That scandal triggered a political uproar in North Carolina, and the settlers west of the Blue Ridge organized a new state government independent of North Carolina. The State of Franklin survived several years until North Carolina regained control and finally executed an acceptable cession of the territory to the US Congress in 1790.30

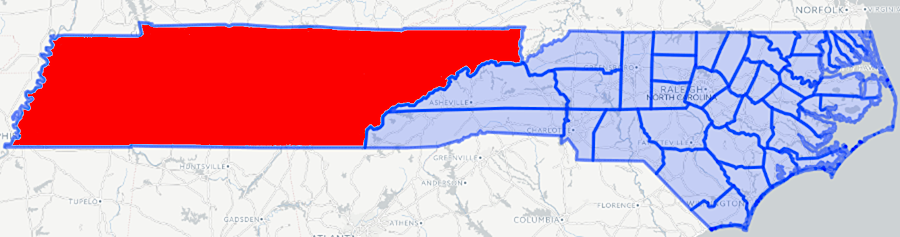

Congress organized the land as the Southwestern Territory, then accepted the State of Tennessee into the union in 1796. Virginia's southwestern border beyond the 1749 Fry-Jefferson line was finally resolved with Tennessee (not North Carolina) through several compromises, including an 1802 survey known as the "diamond line," plus multiple lawsuits.

the modern North Carolina-Virginia-Tennessee border includes a northeast zig-zag between the end of the Fry-Jefferson survey in 1749 and the start of a compromise "diamond line" survey in 1802

Source: USGS, Digital Raster Graphic (DRG) of Grayson 7.5 minute topo quad,

downloaded from University of Virginia Library, Virginia Gazetteer

a marker at Cumberland Gap marks the 1665 colonial boundary, which today separates Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee

In 1858, 1870, and 1871, Virginia and North Carolina proposed to resurvey and re-mark the boundary west of where the 1728 survey (with William Byrd) had ended near Peters Creek. Those initiatives never developed into actual survey projects.

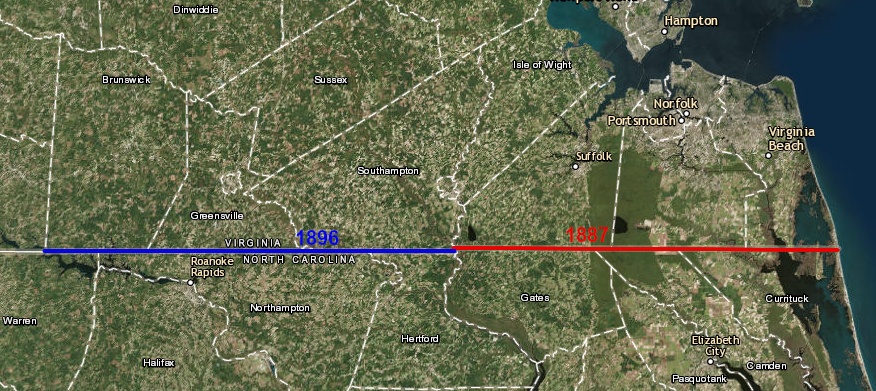

In 1887, the two states did appoint commissioners who oversaw a re-survey of the boundary between the eastern edge at Currituck and the Nottoway River, roughly 60 miles. Surveyors found only one stone thought to date from the 1728 survey, on the Dismal Swamp Canal midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Nottoway River.

The stone was determined to be 600' north of the actual boundary. Local tradition suggested it was not set in place until 1800, over 70 years after the actual survey. That provided an easy explanation for the inaccurate location.

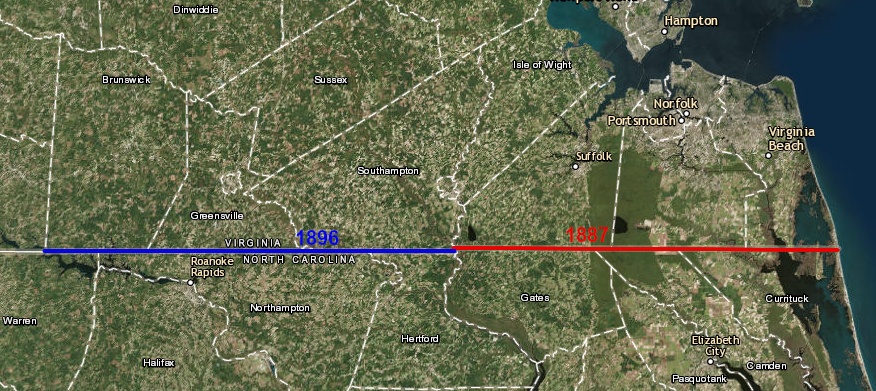

The surveyors set 28 granite monuments in 1888. In 1896, surveyors updated 62 more miles of the Virginia-North Carolina boundary, from the Nottoway River to the western edge of Brunswick County.31

Virginia and North Carolina resurveyed two portions of their border, in 1887 and 1896

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Dismal Swamp Hotel was built on the Virginia-North Carolina boundary, south of where the Feeder Ditch intercepts the canal at Arbuckle Landing. The border location provided unique business opportunities. In its first year, an advertisement for sale of the hotel highlighted:32

- This establishment (being situated on the N.C.-Va line, one half the building in each state) is in a superior degree, calculated to render facilities for matrimonial and duelistic engagements

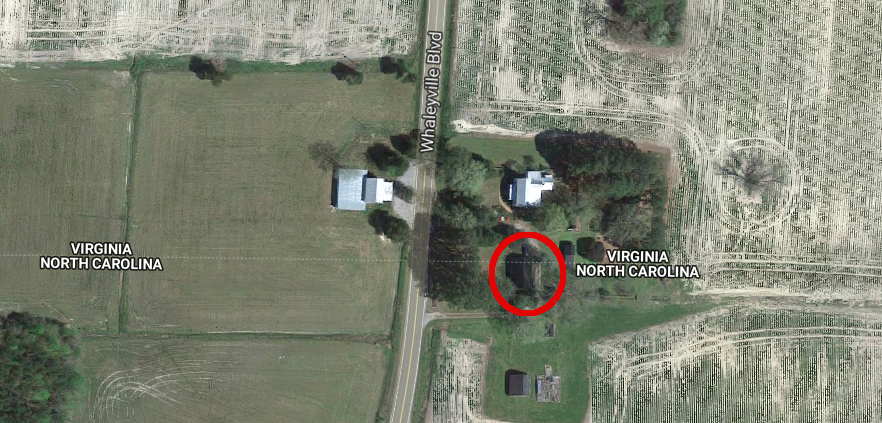

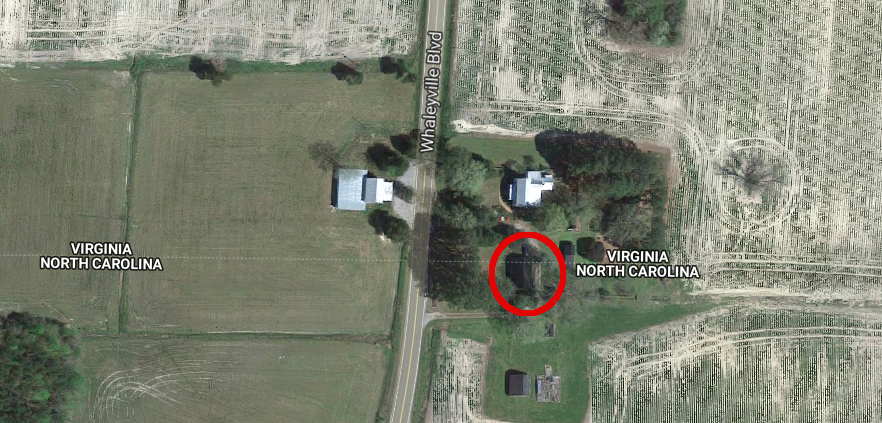

Today, the North Carolina-Virginia boundary cuts through one house next to Route 13. The oldest part of the Freeman State Line House was built in the 1700's. After the 1887 resurvey of the boundary, the kitchen ended up in Virginia but the bedrooms in North Carolina. Mail delivered to their home now, using either a North Carolina or Virginia address, is deposited in the same mailbox in front of the house.

A family that lived there has creatively used their location to maximize benefits from the two separate states. One member qualified for in-state tuition when attending undergraduate school at Old Dominion in Norfolk. He then qualified for in-state tuition to attend graduate school at East Carolina, without having to move.33

the Freeman State Line House on Route 13 is bisected by the Virginia-North Carolina boundary

Source: Google Maps

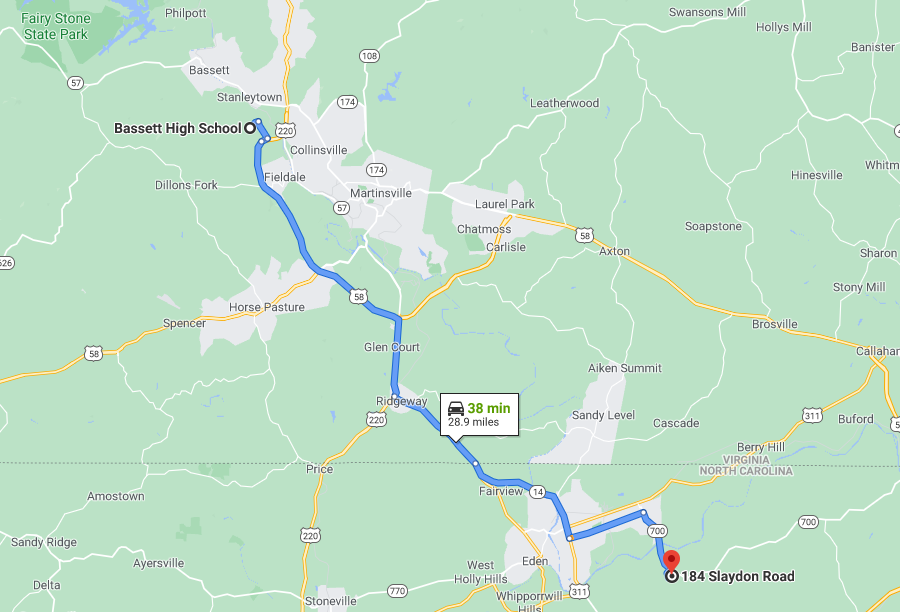

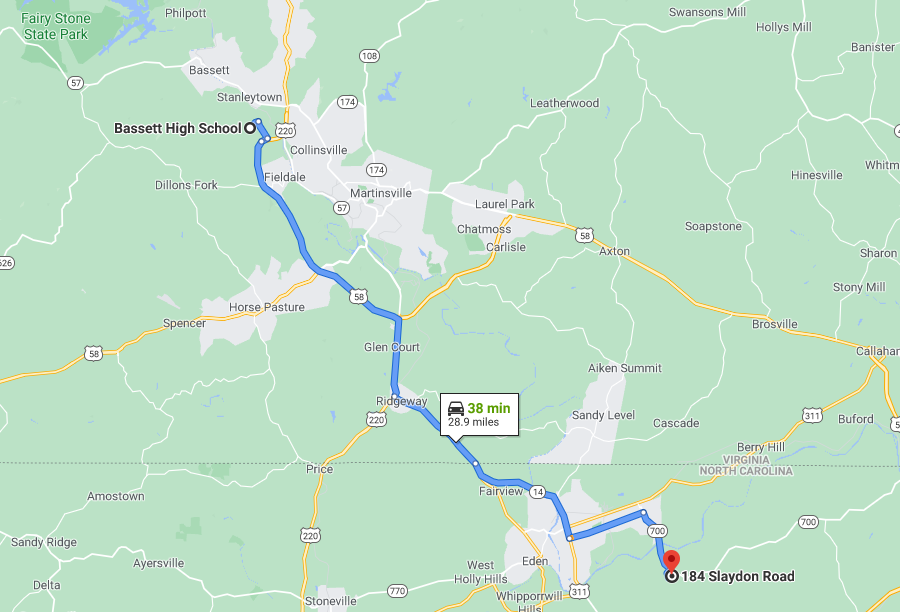

During the COVID-19 pandemic, North Carolina and Virginia adopted different policies for authorizing public gatherings. The sponsors of the prom at Bassett High School in Patrick County took advantage of the state line.

Because Virginia's health orders restricted gatherings to fewer than 25 socially-distanced participants, Pittsylvania, Henry, and Patrick County officials did not plan for 2021 high school proms. However, in North Carolina the guidance allowed 50 people indoors and 100 people in outdoor settings. Patrick County parents organized an unofficial PC Prom by Parents at an event center in Westfield, North Carolina. In Henry County, Bassett High School parents organized the Bengal Bassett Community Prom in Eden.34

in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Henry County parents organized an unofficial high school prom in North Carolina to bypass health restrictions in Virginia

Source: Google Maps

Links

- Albemarle Adventures

- Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy

- Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina

- Carolana

- Code of Virginia - Title 1, Chapter 3.1, Boundaries of the Commonwealth

- Colonial and State Records of North Carolina (from "Documenting the American South" at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

- Letter from Henderson Walker to Francis Nicholson (July 28, 1699)

- Letter from the Board of Trade of England to Francis Nicholson [Extract] (January 4, 1700)

- Minutes of the Virginia Governor's Council (May 12, 1705)

- Minutes of the Virginia Governor's Council (June 26, 1705)

- Letter from the Virginia Governor's Council to the Board of Trade of England [Extract] (August 30, 1706)

- Order by the Virginia Governor's Council concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (October 17, 1706)

- Order by the Virginia Governor's Council concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary

Virginia (October 22, 1706)

- Order by the [Virginia Governor's Council] concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary

Virginia (1706)

- Letter from the North Carolina Governor's Council to the Virginia Governor's Council, including depositions concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (June 17, 1707)

- Depositions of inhabitants of Nansemond County, Virginia concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary

(March 25, 1708)

- Report by the Board of Trade of Great Britain concerning the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (March 14, 1709)

- Journal of Philip Ludwell and Nathaniel Harrison during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (April 18, 1710-November 4, 1710

- Letter from Alexander Spotswood to Edward Hyde (December 15, 1710)

- Proposal concerning the North Carolina/Virginia Boundary (1716), from Governor Spotswood of Virginia to Governor Eden of North Carolina

- Report by Joseph Boone and John Barnwell concerning the North Carolina boundaries (November 23, 1720)

- Report by the Board of Trade of Great Britain concerning general conditions in North Carolina [Extract] (September 8, 1721)

- Journal of the Virginia Boundary Commissioners during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (March 05, 1728-April 5, 1728)

- Journal of Christopher Gale et al. during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (September 20, 1728-October 10, 1728)

- Journal of William Byrd, Richard Fitzwilliam, and William Dandridge during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (September 19, 1728-November 22, 1728)

- Field book of Alexander Irvine during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (March 5, 1728-October 26, 1728)

- Cyndi's List - North Carolina Maps, Gazetteers & Geographical Information

- Daniel Smith's 1779 Journal (for survey of the Walker Line)

- Department of Geological Sciences - University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Division of Earth & Ocean Sciences - Duke University

- Envisaging the West - Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark

- Kentucky-Tennessee Boundary Line - History of Line of 36:30, the Boundary Line Between Virginia and North Carolina and Between Kentucky and Tennessee, by J. Stoddard Johnston, published in The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Volume 6, pp. 23-35

- History of North Carolina Counties

- History of the South Carolina cession, and the Northern boundary of Tennessee by William Robertson Garrett (1884)

- Introduction to North Carolina Maps

- John Lawson Digital Exhibit

- map of 1728 survey - Virginiae Pars, Carolinae Pars

- Moseley Map (1733, 5 years after dividing line survey with William Byrd)

- Newberry Library - Atlas of Historical County Boundaries - North Carolina

- North Carolina Digital History

- North Carolina - Early American Roads and Trails

- North Carolina Geological Survey

- North Carolina Home Page

- North Carolina Map Blog

- ROOTS-L Resources - North Carolina

- State Library of North Carolina

- The Carolina Algonkians

- The Lords Proprietors of Carolina (from the Charleston, South Carolina public library)

- This Land is Our Land! Tennessee's Disputes With North Carolina

- University of Virginia exhibit, Landmarks of American Nature writing - Westward Journeys: Virginiae Pars, Carolinae Pars (1727-8 map of Virginia-North Carolina border)

- US Geological Survey

- Virginia Legislative Information System

- William P. Cumming Map Society

References

1. The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation. Vol. XIII. America. Part II, by Richard Hakluyt, 1589, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25645/25645-h/25645-h.html. See also discussion by Karen Reeds of the first name of Virginia in VA-HIST listserver, 13 February 2009, http://listlva.lib.va.us/scripts/wa.exe?A2=ind0902&L=VA-HIST&F=&S=&P=36464 (last checked June 19, 2009)

2. Charter of Carolina, March 24, 1663, The Avalon Project, Yale University, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc01.asp (last checked August 19, 2009)

3. Letter from Henderson Walker to Francis Nicholson (July 28, 1699), from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0246 (last checked August 19, 2009)

4. Letter from the Board of Trade of England to Francis Nicholson [Extract] (January 4, 1700), from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0254 (last checked August 19, 2009)

5. Minutes of the Virginia Governor's Council, June 26, 1705, from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0313 (last checked August 19, 2009)

6. Charter of Carolina (June 30, 1665), The Avalon Project, Yale University, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc04.asp (last checked August 19, 2009)

7. Minutes of the Virginia Governor's Council, October 24, 1710, from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0398; Journal of Philip Ludwell and Nathaniel Harrison during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary, pp.739-746, 1710 from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0397 (last checked August 19, 2009)

8. Journal of Philip Ludwell and Nathaniel Harrison during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary, 1710, in "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," pp.739-746, http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr01-0397; Julien Negre, "A Straight Line through the Wilderness: Geometry and Geography in William Byrd's Histories of the Dividing line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina (1728 sqq)," Miranda, Volume 6 (2012), https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.5698; William Byrd II, The Secret History of the Line, North Carolina Historical Commission, 1929, pp.91-92, https://archive.org/details/williambyrdshist00byrd (last checked May 7, 2024)

9. Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.17 http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 22, 2015)

10. Mike McNamara, "A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina: The Discovery of a 1737 North Carolina Manuscript Map," Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Volume 33 (2012), http://www.mesdajournal.org/2012/correct-map-province-north-carolina/; Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.8, https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 24, 2019)

11. Report by Joseph Boone and John Barnwell concerning the North Carolina boundaries (November 23, 1720), from "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr02-0201; Alexander Irvine, "Field book of Alexander Irvine during the survey of the North Carolina/Virginia boundary (March 5, 1728-October 26, 1728)," p.799, https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr02-0324 (last checked August 19, 2009)

12. Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.23, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 22, 2015)

13. Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.16-17, p.31, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 22, 2015)

14. "Proposals For Determining The Controversy Relating To The Bounds Between The Governments Of Virginia And North Carolina," by Alexander Spotswood and Charles Eden, 1716, in "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina," Documenting the American South, http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0111 (last checked June 23, 2018)

15. "Virginia and North Carolina Boundary Line," http://www.surveyhistory.org/va_&_nc_bounary_line.htm, Surveyors Historical Society, January 1994 (last checked August 19, 2009)

16. "Northern Boundary of Tennessee," The American Historical Magazine, Volume 6, Number 1 (January, 1901), pp.24-25, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42657520 (last checked November 16, 2024)

17. Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.56, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 22, 2015)

18. "Virginia and North Carolina Boundary Line," http://www.surveyhistory.org/va_&_nc_bounary_line.htm, Surveyors Historical Society, January 1994 (last checked August 19, 2009)