Paleo-Indians shared geographic knowledge to communicate about the best paths to locations of special value

Paleo-Indians shared geographic knowledge to communicate about the best paths to locations of special value

The Paleo-Indians were Virginia's first geographers.

From the time they initially arrived, they must have shared information about what they had discovered and where they planned to travel. Hunting bands would have intersected each other by accident, but it is probable that they scheduled rendezvous as well to trade, socialize, and select partners from unrelated groups for starting new families.

Some natural features provided easy-to-recognize places for gatherings, and those who have been to a rendezvous in the past must have transmitted to others the directions to those locations. Archeologists studying a Paleo-Indian site at Leesville Lake think the Smith Mountain Gap was a site for repeated gatherings, while valuable quarries such as the Thunderbird site on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River would have been remembered by sharing geographic knowledge across the generations.1

The original inhabitants of Virginia drew maps in the dirt and scratched pieces of bark, to show others in the band where to hunt or gather food. When John Smith began to explore the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, he quizzed the various Native Americans which he encountered about their geographical knowledge.

On the Eastern Shore he discovered they knew the local territory well, and could communicate it effectively - presumably using graphics, rather than words in a language the English could barely comprehend:2

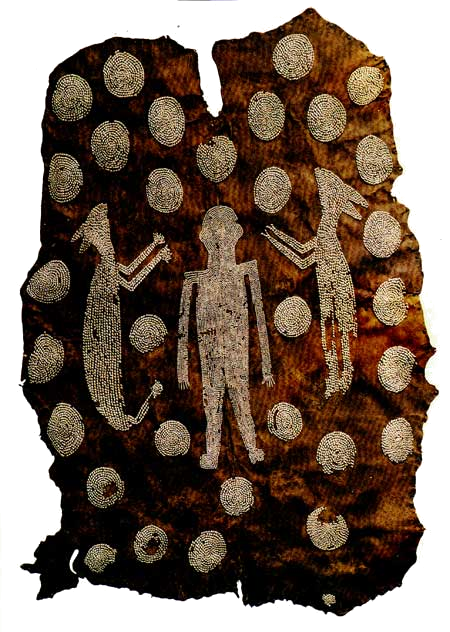

Very few maps produced by the Native Americans have survived. Those scratched in the dirt, assembled by arranging sticks and other objects on the ground, or scribed on bark have long since disappeared. A few surviving skins with circles may indicate the relationship between leaders and places, but it is almost impossible to identify the relative locations or distances between places from the patterns on those remaining "maps."3

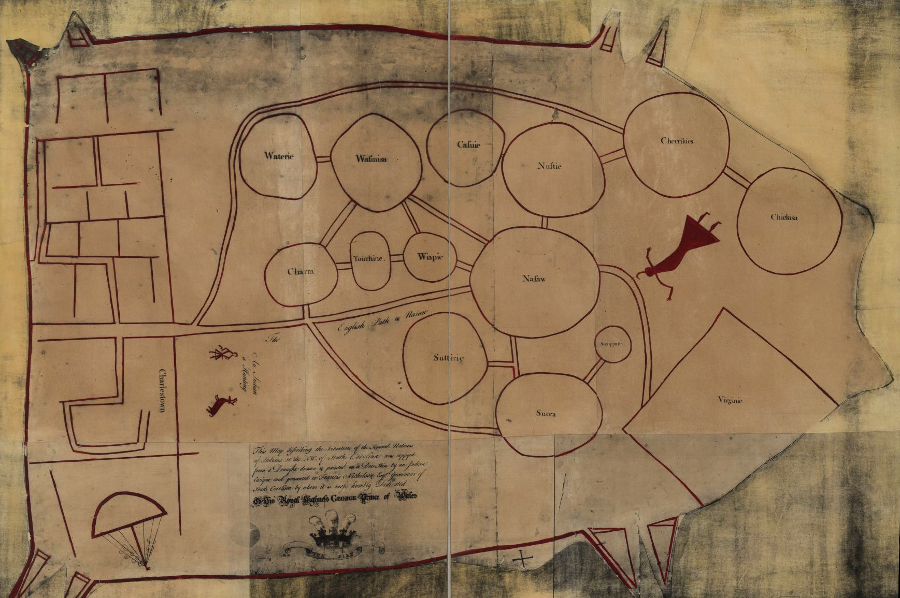

the Catawba Deerskin Map may indicate the relative location of different Native American groups in the Carolinas

Source: Library of Congress, the Catawba Deerskin Map

the 34 circles on Powhatan's Mantle (now at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England) may indicate his control over that number of tribal units in Virginia, but their geographic location is not identifiable

Source: National Park Service, A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

Many more European maps have survived. Sailors from many nations had scouted and mapped the Atlantic shoreline for a century before the English began to colonize North America in the early 1600's. Today, Virginia has 10,120 miles of shoreline. Of them, 132 miles are along the Atlantic Ocean, 7,213 miles along tidal bays, and 2,775 miles along inland bays/lagoons.4

Westmoreland County shoreline on the Potomac River at Coles Point

The sailors could measure latitude in the 17th Century, but it was not until the late 1700's that the English created the technology to measure longitude (a clock that could travel on a ship, and measure the time differential between the ship's location and Greenwich).

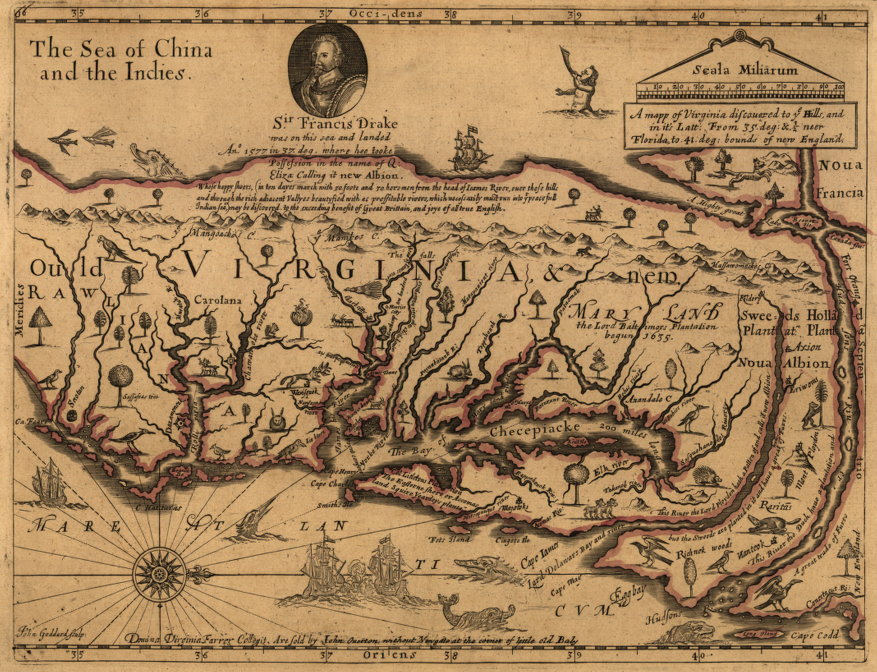

Most of the North American continent was still "terra incognita" or unknown land to the Europeans throughout the 1600's. That is why the early Virginia maps have reliable information on Virginia's latitude and Chesapeake Bay, mixed in with wildly hypothetical information about the longitude and the lands west of the Fall Line. Without longitude information, early explorers did not understand how far west the North American continent stretched.

John Farrer's 1667 map, showing presumed location of Pacific Ocean just west of the Blue Ridge Mountains

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it's latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England

The mythical Northwest Passage is still on John Farrer's map. On the far right, he mapped the mythical Northwest Passage water connection between the Atlantic and Pacific (Sea of China and the Indies) oceans.

According to John Farrer, the Hudson River connects to the Pacific Ocean,

just on the western side of the Blue Ridge

Northwest Passage on John Farrer's 1667 map

(map is oriented to north is to the right)

Source: Library of Congress

If that water passage had actually existed, then the cost of shipping between Asia and Europe would have been dramatically reduced, and the Panama Canal would not have been necessary. For 150 more years after John Farrer's map was published, explorations continued for a low-cost water connection across the North American continent. Only after two Virginians, Lewis and Clark, returned in 1806 from their journey across the continent was clear that the headwaters of the rivers of North America did not offer an easy opportunity for a canal to connect the Mississippi River with the Pacific Ocean.

A close look at the numbers on the very bottom of John Farrer's map show that the latitudes for the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay are relatively accurate.

That knowledge of latitude colored expectations of what would be discovered in the New World that was still unexplored by Europeans. Those Europeans knew where the 36th degree parallel of latitude crossed Europe. The Europeans assumed the climate and crops in Virginia might be comparable to what they experienced at 36° north latitude around the Mediterranean Sea. That's why the early colonists tried to plant oranges in Jamestown - after all, oranges grew in Spain, at the same latitude in Europe.

Straights of Gibraltar (Source: NASA)

When John Smith and John Farrer published their maps of Virginia in the 1600's, they oriented "west" rather than "north" at the top of their documents.

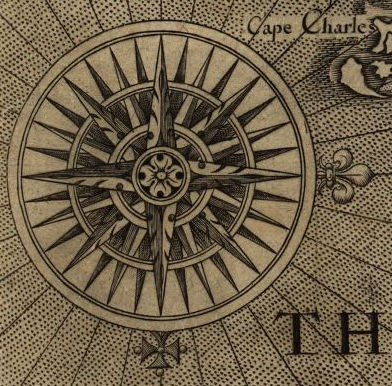

the rose on John Smith's 1612 Map of Virginia points west, rather than north

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606; graven by William Hole

When eyes of modern readers move from the bottom to the top of their old maps, the eyes are traveling to the west - inland. The maps are oriented for a sailor approaching the East Coast of North America in the 17th Century.

the rose on John Smith's 1612 Map of Virginia had 32 points separated by 11.25 degrees (in contrast to 36 lines separated by 10 degrees on modern compasses)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606; graven by William Hole

John Smith's Map of Virginia (with "west" at the top of the map and "north" to the right)

Source: Library of Congress

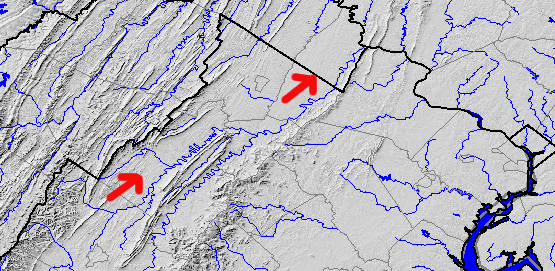

In contrast, almost all the maps published in the 21st Century are oriented so north is at the top of the map. Maps on a wall have north at the top, closest to the ceiling. That convention makes it easy to confuse "north" with "uphill" and "south" with "downhill" - so think twice, and don't assume North=Up.

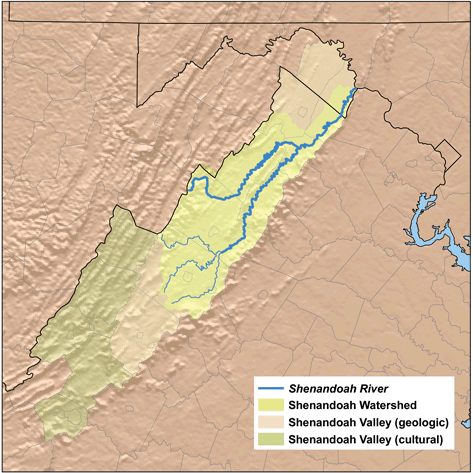

For example, the Shenandoah River flows north from Augusta County towards its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry. The Shenandoah River does not defy gravity and flow uphill. The Shenandoah River flows "down the valley," downhill towards Harpers Ferry. Travelers going from Harpers Ferry south to Staunton are going "up the valley" - at least in regards to elevation.

Modern mapping tools, including Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, allows users to trace their path as they drive in a car. However, GPS units with millimeter accuracy thanks to satellite and cell tower links are only as accurate as their underlying maps. When roads change, GPS units end up being... wrong. Drivers can be instructed by navigation systems to go in the wrong direction on a divided highway, when a two-lane road is expanded to four lanes but old maps still tell drivers to "turn left" prematurely.

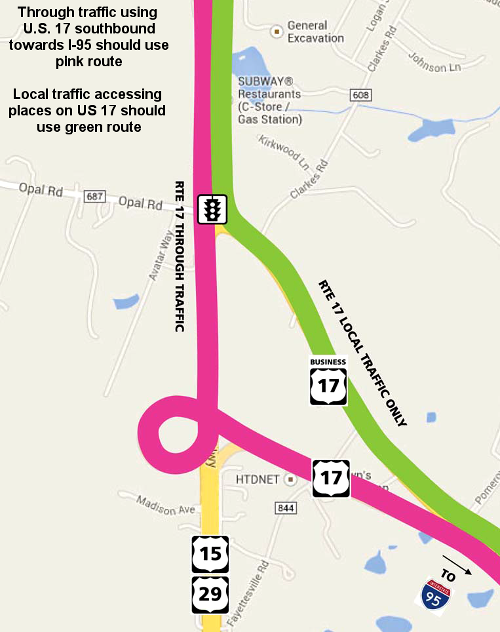

When the Virginia Department of Transportation built a new interchange for Route 17/Route 29 at Opal in Fauquier County, drivers continued to go to the old intersection and perpetuated congestion in the left-turn lanes. The VDOT District Administrator noted that modern drivers were more focused on out-of-date maps encoded in their electronic mapping tools and not paying attention to the real-world:5

a new intersection at Opal (in Fauquier County) confused drivers until maps in computerized navigation systems were updated

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Flyer: New traffic pattern at Opal

The longest physical map in Virginia is located at the courthouse in the City of Chesapeake. The almost 59-foot long map is a plat of the 22-mile-long Dismal Swamp Canal.6

Geographic Information System (GIS) data is available at clearinghouses, including:

Historic maps of Virginia that have particular value include:

John Smith had no timepiece to help define longitude, and miscalculated the width of the Eastern Shore

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606; graven by William Hole

Theodor De Bry printed John White's map in 1590, becoming the first to use the place name "Virginia"

Source: Library of Congress, Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta (1590)

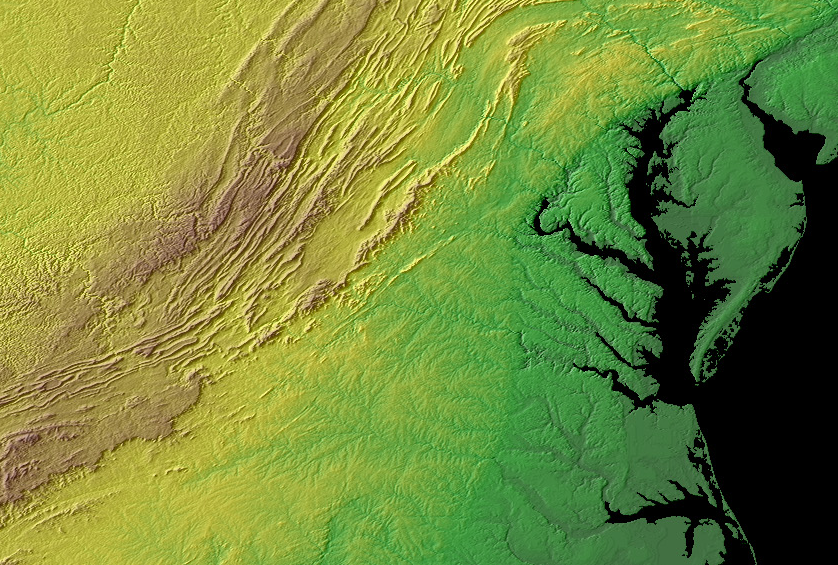

topography of Virginia and adjacent area

Source: NOAA Global Land One-km Base Elevation Project (GLOBE): A Gallery of High Resolution Images

Shenandoah River - direction of flow is north, but the water flows downhill

Shenandoah Valley

Source: Wikipedia, created by Karl Musser based on USGS data

in 1783, Virginia extended to the Mississippi River

Source: National Archives, Map of the United States of America Laid Down from the Best Authorities Agreeable to the Peace of 1783