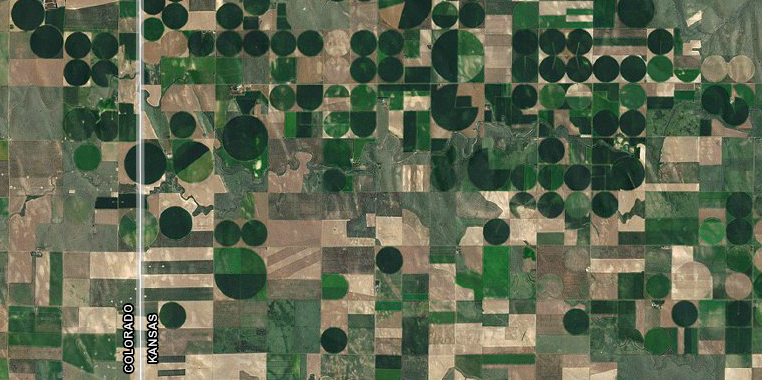

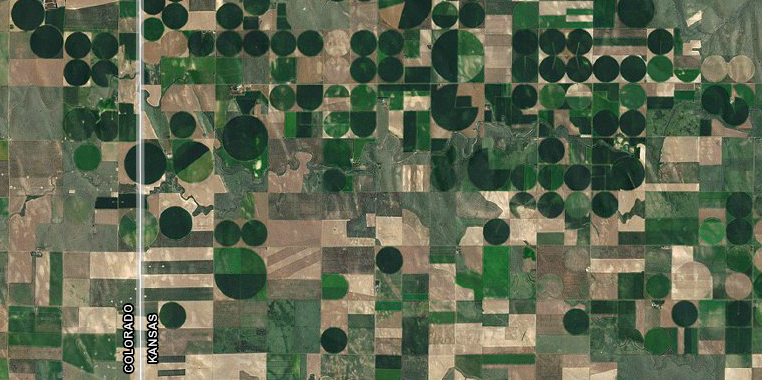

irrigation in western states with low rainfall have created land use patterns rarely seen in Virginia

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

irrigation in western states with low rainfall have created land use patterns rarely seen in Virginia

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Most states in the eastern United States follow the riparian rights concept. In Virginia, property owners with land adjacent to a river or lake (riparian landowners) are entitled to withdraw water from the water body. The water must be used on the riparian property; it cannot be exported to land away from the river's edge and owned by different people. In Virginia no more than 50% of the streamflow may be diverted for a single property without a state permit.

Where there is plenty of rainfall, there is little need to limit access to water or to control its distribution. Landowners can place a pipe into the nearest creek to obtain water for drinking, irrigation, or industrial use. The Department of Environmental Quality now regulates large-scale (greater than 10,000 gallons per day) surface water withdrawals (including wetlands, stream channels, lakes, springs, and ponds, but excluding groundwater) under the Virginia Water Protection Permit (VWPP) Program, but the right to the water is based on ownership of adjacent land.

In contrast, western states receive far less rainfall, so water is scarce and the doctrine of prior appropriation evolved. After the Native Americans were displaced, settlers and miners created water distribution systems, digging ditches to move water from rivers to mines or farmland that was not adjacent to a water body. Local irrigation districts defined water rights, assigning the highest priority for water during droughts to the first people to apply water for a beneficial use. Today, state agencies maintain records of water rights, and state courts adjudicate competing claims for priority.

Riparian land ownership does not grant priority - the land with the oldest ("senior") water right could be located far from the natural river. Under the doctrine of prior appropriation, in times of drought, ditches are controlled so water flows to the land with the oldest water rights, and irrigation pumps might be turned off for property adjacent to a river.

The word "desert" is applied to areas receiving less than 10 inches of rainfall annually. In a different climate west of the 100th Meridian, a reliable supply of fresh water is well worth a fight - or the investment to capture excess water in a distant watershed and pipe it to the area with a high demand.

Cities in one area that have maxxed out the supply within their watershed engage in "inter-basin transfers," building dams and reservoirs and pipelines to transport water from other watersheds. Tucson, Arizona is far from the Colorado River - but the Central Arizona Project has brought the river's water to the city. The adage that "water flows uphill to money" is true.

Virginia lacks irrigation ditches - and did not need to assemble political coalitions to obtain Federal funding for irrigation projects

Source: Bureau of Reclamation Photo Gallery, Central Arizona Project Canal

Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting... is a traditional phrase in the Western United States. Los Angeles' capture of Owens River and Mono Lake water was dramatized in the movie Chinatown. Denver has fought similar wars with the western part of Colorado, and Las Vegas with the communities upstream in Northern Nevada. Courts have had to adjudicate water rights for all users on some rivers to resolve the conflicts, and in some cases water compacts that settle multi-state water wars have been approved by the US Congress.

Virginia is beginning to face water allocation challenges, requiring adjustments to the traditional riparian water rights system. After the 2002 drought, local governments were required to develop water supply plans to meet projected demand for water, up to the year 2040. Like the western states, the state government is getting involved in tracking and regulating water withdrawals.

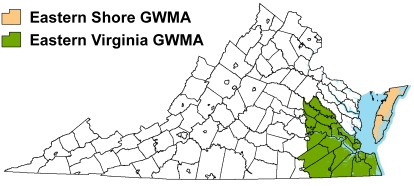

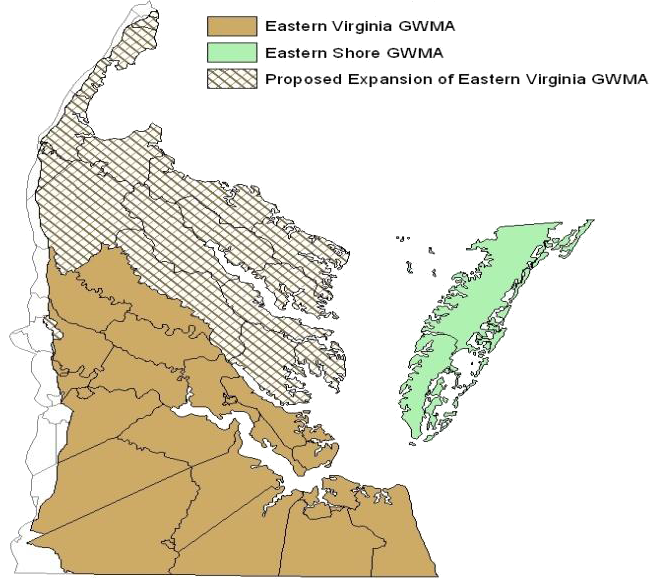

Western states manage water rights to the last drop, but the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) focuses on just larger withdrawals. Withdrawals from nontidal waters that total less than 300,000 gallons in any single month (for agriculture, less than 1,000,000 gallons) do not require a Virginia Water Protection (VWP) Permit. Ground water is not controlled by the state except in two Ground Water Management Areas, where 300,000 gallons in any single month is normally the threshold for requiring a state permit. In 2013, DEQ proposed expanding the Eastern Virginia Ground Water Management Area to include the entire Coastal Plain, because:1

in Ground Water Management Areas, no permit is required for withdrawals for a heat pump if the ground water is reinjected into the aquifer from which it was withdrawn

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Ground Water Withdrawal Permitting Program

The first serious water shortages in Virginia appeared in the Hampton Roads area. Surface water sources have been fully utilized, and groundwater sources are limited (especially in areas affected by the bolide's impact 35 million years ago). Virginia Beach succeeded in tapping a water source from a distant watershed (the Roanoke River), but Newport News was blocked in its effort to draw water from the Mattaponi River when the Corps of Engineers rejected a permit for the King William Reservoir. For the moment, Newport News must still rely upon the Chickahominy River as its primary source of drinking water.

In Virginia, most water pumped from the ground or piped from the rivers is used for drinking ("public water supply"). Virginia's initial colonial settlements relied upon springs and wells; the first well at Jamestown was dug in 1608. In Clark County, 75% of the residents still rely upon groundwater, pumped to the surface through wells, but most urban areas have exhausted the supply available from springs and rely upon surface water.2

expansion of the Eastern Virginia Ground Water Management Area was proposed due to declining groundwater levels throughout the Coastal Plain

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Status Of Virginia’s Water Resources (2013 report, p.19)

The City of Winchester used the spring at Hollingsworth mill as its main water supply until 1956, but now takes water from the North Fork of the Shenandoah River. Despite the abundant groundwater available in the limestone sediments of the Shenandoah Valley, the Town of Front Royal has a Virginia Water Protection Permit to withdraw 4 million gallons/day (MGD) from a combination of intakes on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, Happy Creek, and Sloan Creek.

Most drinking water systems in Virginia were created in the 20th Century to supply cities, long before the surrounding counties urbanized to an equivalent level of development. As a result, the late-to-urbanize counties have either negotiated to purchase drinking water from the cities, or built independent systems to service county customers.

The City of Fairfax needed additional water in the 1950's, as expansion of the Federal government (especially the military) in World War Two and the Cold War stimulated population growth in Northern Virginia. The city had no additional sources of water within its boundaries, so it went west to Loudoun County and dammed Goose and Beaverdam creeks.

The city piped the water to serve residents of the city, and had no interest in selling water to customers in Loudoun/Fairfax counties along the distribution line. The city's pipeline goes down Hunter Mill Road, but the Town of Vienna and Fairfax County ended up utilizing separate water sources and building independent systems for their drinking water. Only a few of the city's customers were located outside the cty's boundaries.

In 2012, the City of Fairfax considered merging with the county's Fairfax Water utility, to reduce the costs of upgrading the city's old water treatment plant located in Loudoun County. Fairfax City initially opted to maintain its own system, but later chose to consolidate with the county's system (Fairfax Water) rather than duplicate infrastructure. The city manager highlighted that the initial decision was more political than economic:3

Because the City of Fairfax had dammed Goose Creek for its water utility, Loudoun County was unable to tap its local creeks when it urbanized in the 1990's. Loudoun was able to purchase drinking water from the City of Fairfax and from Fairfax County, but proposals to "control the future of the system" required examining more-expensive solutions. Loudoun Water decided to establish an independent system, to ensure a reliable supply for Loudoun customers without depending upon contracts with external utilities tied to political jurisdictions who competed with Loudoun to attract businesses.

Loudoun developed a plan to "bank" wintertime flows in the Potomac River. The water will be pumped from the river, when there is an excess of flow, to an old rock quarry. The quarry will serve as a reservoir, storing the water until it is needed during the summer. That strategy required waiting until the quarry's rock was exhausted, rughly around the year 2020.

Loudoun Water's long-range plan is to "bank" Potomac River water in Quarry A, eliminating the need to purchase drinking water from rival Fairfax County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS

Loudoun accelerated its water independence in early 2014, by purchasing the assets of the City of Fairfax water utility that were located within the county. Loudoun Water acquired the Goose Creek Reservoir, Beaverdam Reservoir, and Fairfax City's old water treatment plant. The city no longer needed its own water supply system, after City Council finally agreed to rely upon Fairfax Water in order to avoid the high costs of upgrading the water utility infrastructure.4

In areas with political tension, where the "community" is defined by a political boundary, you can see service areas defined by the straight lines created by city charters and later annexation, rather than topography and natural divides. The customers have paid for different reservoirs and water treatment plants and pipelines, because politics really does makes water run uphill.

In Virginia, the 1998-99 drought showed that many communities lacked pipeline connections that would allow adjacent political units to sell large amounts of water to each other. Political geography does not reflect the physical geography in many areas, and political disconnects were mirrored by pipeline disconnects.

Some Virginia cities and counties have created unified "service authorities," consolidated utility systems to distribute water based on watersheds and gravity rather than political boundaries. After the 1998-99 drought, Roanoke County and Roanoke City finally agreed to construct new facilities to share water between the jurisdictions, after years of rival planning and refusing to partner with each other.

Water law in the eastern United States is evolving to address water rights issues... or wrongs, depending upon your point of view. Most legal fights are triggered by proposals to pump water across a watershed divide, transferring water from one river basin to another. Water supply plans typically predict increases in future demand over the next 20-50 years, based upon projections of population growth and economic development.

Occasionally, projections of increased conservation are also incorporated in the planning. Plans by the Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority to raise the height of the Ragged Mountain Dam, in order to increase the water supply from the South Fork Rivanna River for Charlottesville and Albemarle County, triggered an extensive debate over how conservation could reduce the future demand and thuis minimize the area that would be flooded by a higher dam.

Exporting water from one watershed may address projected shortfalls in the "receiving" watershed, but reduces the potential growth of the "sending" watershed. The Danville-Pittsylvania County Chamber of Commerce has objected to proposals to export Dan River water to the Greensboro Triad region of North Carolina:5

The Dan River is a tributary to the Roanoke River, which flows into the Kerr Reservoir on the border of Virginia and North Carolina. The competition between the two states on allocating water stored in that reservoir could trigger a change in traditional water allocation procedures.

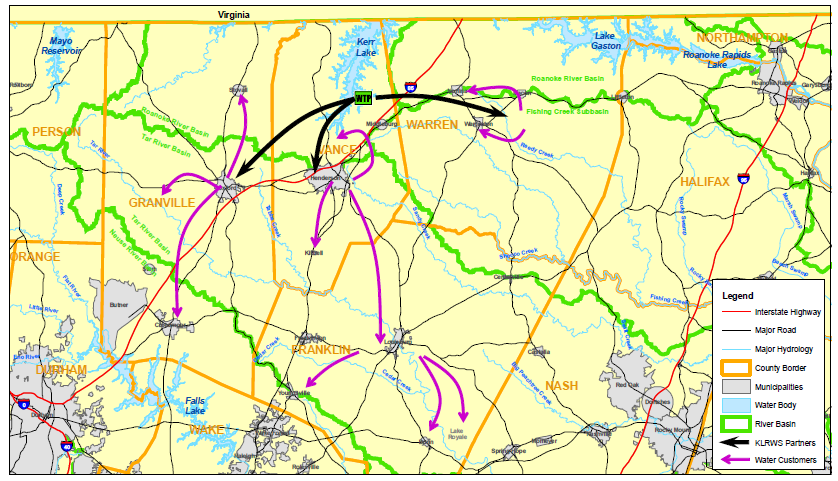

proposal to export Roanoke River water to other river basins in North Carolina

Source: Kerr Lake Regional Water System Interbasin Transfer Request from the Roanoke River Basin,

Scoping Document, Interbasin Transfer Certificate and Environmental Impact Statement

In 2009, the Kerr Lake Regional Water System in North Carolina requested state approval for an interbasin transfer from a portion of Kerr Reservoir in North Carolina (in the Roanoke River basin) to river basins further south in North Carolina. All the water would move from one place in North Carolina to another place within the state, but Roanoke River water would be pumped over the watershed divide ionto other watersheds. The proposal would shift up to 24 million gallons per day from the Kerr Reservoir to the Tar River and Fishing Creek basins, plus up to 2.1 mgd million gallons per day from the Kerr Reservoir to Neuse River basin.6

While the Virginia DEQ claims the authority to approve interbasin transfers for watersheds within Virginia, interbasin transfers moving water across state boundaries are expected to end up in court. One or more Federal judges will get the final word, unless states negotiate solutions and Congress resolves an interstate issue through an "compact" that each state must adopt.

Assumptions about who owns the water in Virginia may be revised to match debates regarding projects that draw water out of the Colorado River basin for Denver, Phoeniz/Tucson, and Los Angeles.

In land use planning dreams, people would move to the resources, rather than modify the natural environment to move the resources - like water - to excessive concentrations of people. However, people in Virginia communities don't passively accept natural limits on water supply any more than their Western counterparts.

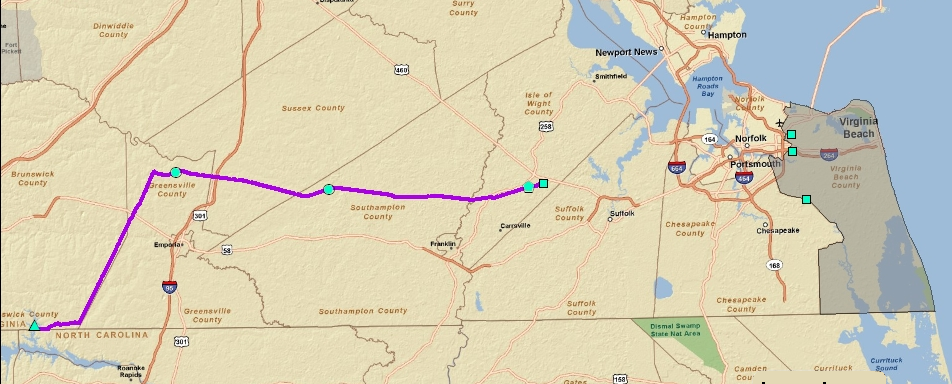

However, population growth near existing water sources in Danville or Appomattox lags behind growth in Hampton Roads. Being near the bay and the ocean, and the higher-paying jobs in the urban area, is drawing more residents than Southside Virginia farm country. As the Hampton Roads area has grown in Virginia, water distribution battles have heated up between Virginia Beach and North Carolina over a water pipeline from Lake Gaston (an interbasin transfer from the Roanoke River), and between Newport News and the Mattaponi Tribe over a proposed reservoir moving Mattaponi River water across the watershed divide to a city on the James River.

pipeline carrying water out of Roanoke River basin to supply Virginia Beach

Source: Kerr Lake Regional Water System Interbasin Transfer Request from the Roanoke River Basin,

Virginia Beach, Lake Gaston Water Supply Pipeline

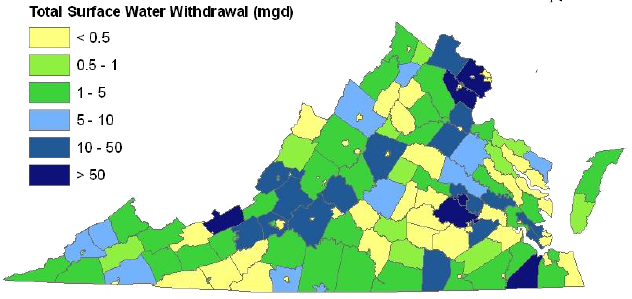

while groundwater withdrawals are concentrated in the Valley and Ridge and Coastal Plain physiographic provinces, surface water withdrawals are widespread in Appalachian Plateau and Piedmont

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Status of Virginia's Water Resources - A Report on Virginia’s Water Resources Management Activities (October 2012)

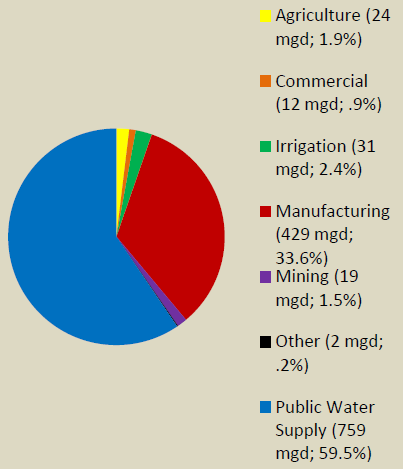

irrigation for agriculture is a minor component of water use in Virginia - most water is used for drinking water supplies and manufacturing (especially paper)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Status of Virginia's Water Resources - A Report on Virginia’s Water Resources Management Activities (October 2013, p.28)

1. "VWWPP and VWPP Fact Sheet," Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, http://www.deq.state.va.us/Portals/0/DEQ/Water/WaterSupplyPlanning/VWP_VWUDS_handout_2013.pdf; Status Of Virginia’s Water Resources: A Report on Virginia’s Water Resources Management, Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, October 2013, http://www.deq.state.va.us/Portals/0/DEQ/Water/WaterSupplyPlanning/WRreportfinal2013.pdf(last checked November 3, 2013)

2. "Northern Shenandoah Regional Water Supply Plan," July 26, 2012, pp.9-14, http://www.winchesterva.gov/documents/government/city_council_meetings/Drought-Management-and-Water-Conservation-Plan.pdf (last checked November 4, 2012)

3. "Fairfax City Opts to Keep its Water System," Falls Church Times, June 18, 2012, http://fallschurchtimes.com/35678/fairfax-city-opts-to-keep-its-water-system/ (last checked November 4, 2012)

4. "Loudoun Water Purchases Beaverdam, Goose Creek Reservoirs," Leesburg Today, February 3, 2014, http://www.leesburgtoday.com/ews/loudoun-water-purchases-beaverdam-goose-creek-reservoirs/article_43473838-8cde-11e3-8ef7-0019bb2963f4.html (last checked February 12, 2014)

5. "2011 State Legislative Policy," Danville Pittsylvania County Chamber of Commerce, http://www.dpchamber.org/files/461.pdf (last checked November 3, 2012)

6. "Kerr Lake Regional Water System Interbasin Transfer Request," presentation for April 1 through 8, 2009 Public Meetings by CH2MHill, http://www.ncwater.org/Permits_and_Registration/Interbasin_Transfer/Status/Kerr/KLRWS_Public_Meetings_042009.pdf (last checked November 3, 2012)

7. "Who Owns the Water?" in Virginia Water Policy: Legacy and Challenges, Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, May 23, 2003, http://www.deq.virginia.gov/waterresources/pdf/fisher523.pdf (last checked September 11, 2011)