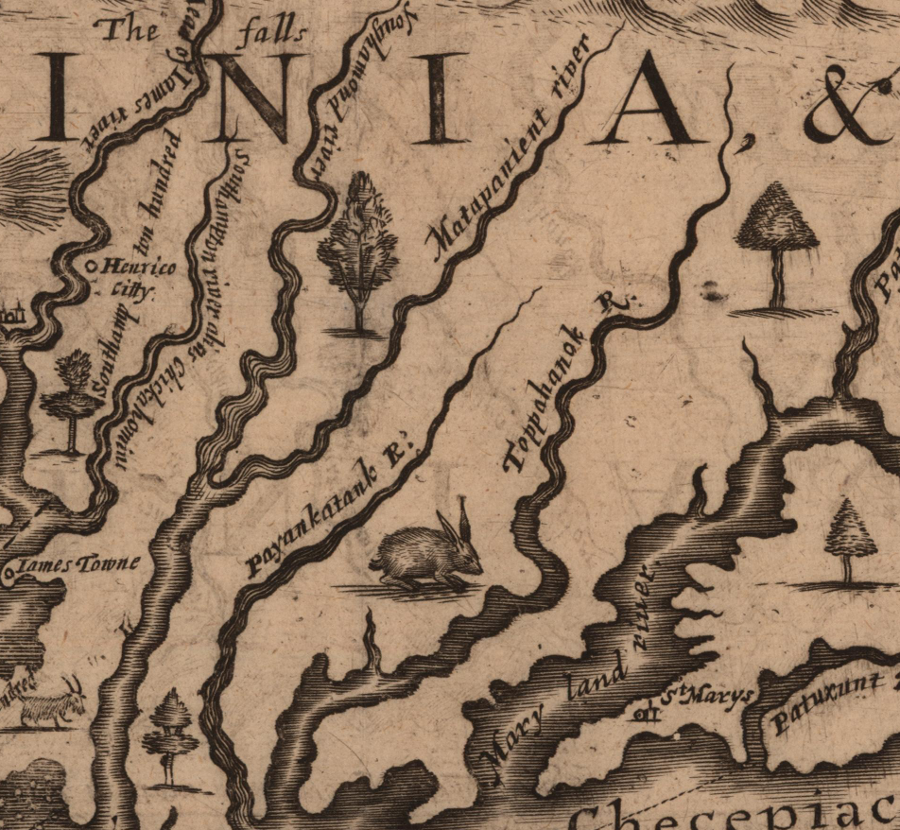

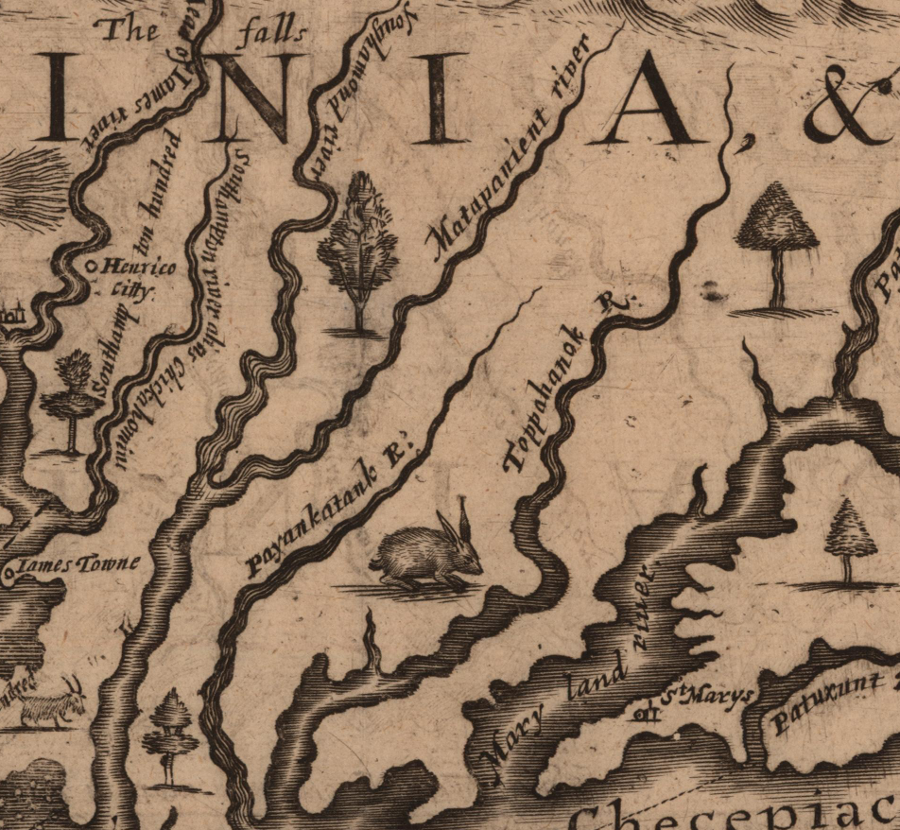

River Names in Virginia

Native American names for some Virginia rivers have survived in altered form - the Youghamond is now the Pamunkey, the Matapanient is now the Mattaponi, and the Toppahanock is now the Rappahannock

Source: John Carter Brown Library, A mapp of Virginia discouered to ye Falls, and in it's Latt: From 35 deg: & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg: bounds of new England (by John Farrer in 1651)

As Virginia was settled by Europeans, they adopted some of the Native American names for different places. Many of those names still remain:1

Chickahominy

Chowan(oke)

Mattaponi

Meherrin

Nansemond

Nottoway

Occoquan

Pamunkey

Piankatank

Poquoson

Poropotank

Potomac

Powhatan (now just a creek in James City County)

Rappahannock

Roanoke

Shenandoah

Wicomico

Yeocomico

The English immediately assigned their own names, after arriving in 1607. The Algonquian-speaking Native Americans did not refer to the James river before 1607; they had already honored their paramount chief by naming the biggest river after Powhatan.

Above the Fall Line in territory not controlled by Powhatan, the Siouan-speaking residents called it the Monacan River. A 1676 map, the "New Description of Carolina," still used Powhathan for that river below the falls.1

A 1686 visitor from France understood the English words for the James River, but spelled the word as he heard it - "Gemerive." He also referred to the Pethomak (Potomac) River, and wrote about Cape Charles and Cape Henry at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay as the "Cap de Bies." Various arms of the Chesapeake Bay were "Bees" rather than "bays," and Jamestown was spelled "Jemston."2

Virginia is named for Queen Elizabeth, who remained unmarried and therefore "virgin," but the Elizabeth River is not named for that queen. The river's name honors the daughter of James I, also called Elizabeth. The English who arrived in 1607 had previously honored the sons of the king by naming Cape Henry after her older brother and Cape Charles after her younger brother. Princess Elizabeth got a river named after her when she was 11 years old.

Five years later, when she was 16 years old, she was married to the German prince Frederick V. He was the "Elector" of Palatine, but a year after the marriage was forced into exile during the Catholic-Protestant wars in Europe. Despite the loss of her territory, Elizabeth's royal status was essential two generations later. After Queen Anne died in 1714, Elizabeth's grandson was crowned King George I of England. That established the Hanover dynasty, which was renamed the House of Windsor in World War I. The ruling family in England, including Queen Elizabeth II, can be traced back to the Elizabeth for whom the river was named.3

On the 1676 map, swamps southwest of the Elizabeth River were labelled Black Waters. The distinctive color of the water, stained by tannins from vegetation decaying in the swamps, would have been obvious to anyone. Today's Blackwater River forms the border between today's Isle of Wight and Southampton counties. Blackwater could an original Native American name translated into English, or the original name could have been lost and today we use a term created by the early European explorers.

Blackwater River, defining boundaries of Isle of Wight and Southampton counties

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Franklin 7.5 x 7.5 topographic quadrangles (Revision 1, 2013)

Though we can't be positive, the Rivanna is probably a merging of the words for the "river Anne." The Fluvanna ("fluvial Anne") was probably named for Princess for Pricess Anne as well. She became queen of England after the deaths of King William and Queen Mary. In the 1600's, as English settlers explored up the James River, they discovered a fork where two large streams came together to form the James. The north fork was called the Rivanna, the south fork the Fluvanna, and the junction was called Point of Fork.

During the Revolutionary War, Point of Fork was a key point for storing supplies for the rebellious Virginians until the British captured it in 1781. The town at that spot is called Columbia now, and the south fork was renamed the James River after further exploration revealed that fork extended much further than the Rivanna. Today the start (headwaters) of the James River is at the confluence where the Jackson and Cowpasture rivers join, just downstream of Clifton Forge.

The New River was first named Woods River, for the sponsor of the first exploration party to see it. After being rediscovered by other explorers, the Woods River apparently was renamed.

Further west, the Holston, Powell, and probably the Clinch rivers were named for early explorers or settlers. By the time Europeans settled the southwestern region of Virginia between 1750-1800, the local natives - with their local place names for the rivers - had already been displaced. (It was Shawnee coming from Ohio, and Cherokee from Tennessee, who attacked Daniel Boone and others as they created the Wilderness Road and the first farms in Southwest Virginia.)

Many of the rivers in Tidewater Virginia, the area first explored and settled by the English, are still called by their old Algonkian names. The Appomattox, Nottoway and Meherrin rivers retain the names of the Native Americans who lived there when the English colonists arrived, but most place names used in Virginia today are replacements imposed by the late-arriving colonists.

the Nottoway and Meherrin rivers retain the names of the Native Americans who lived there when the English colonists arrived

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Occoquan supposedly means "at the end of the water," where the freshwater stream ended in the brackish Potomac. The word may mean "a grove of trees," but there are none of the original Dogue still around to share the oral history.4

Sometime between 1900-1910, maps began to refer to Occoquan Creek instead of Occoquan River. In the 1970's, Roemary Selecman campaigned successfully to get the Board of Geographic Names to modify the official Federal maps to refer to the Occoquan as a river instead of a creek. She won a half-victory. The Virginia Department of Transportation recognizes the Occoquan River is a "river" on signs near the Town of Occoquan, but persists in using Occoquan "Creek" on signs near Lake Jackson.5

Occoquan was a creek on the 1966 USGS quadrangle map - but by 1977, the Occoquan was a river...

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), 7.5 x 7.x topographic quadrangle map (1966); US Geological Survey (USGS), 7.5 x 7.x topographic quadrangle map (1977)

Rappahannock supposedly means "rise and fall of water," reflecting the patterns of the tides. Documentation of the name for Stingray Point at the mouth of the Rappahannock River is more complete. That site got its name from Captain John Smith's painful encounter with a stingray.

"Shenandoah" was thought for decades to mean "daughter of the stars," though evidence for that claim is thin. "Potomac" supposedly means "trading place." It is hard to be confident in the translations of the place names used by the local Native Americans. The translations and the spellings may have been modified substantially by the English settlers.

An alternative interpretation for the Potomac name has more spice to it. One translation has Potomac meaning "the place to which tribute is brought," in reference to reported contributions provided to the Iroquois, so they would stay away from the Algonkian settlements. That name for the river that runs past the headquarters of the Internal Revenue Service may be particularly appropriate each April 15.

Restoring the original names is not outside the realm of possibility. Canada renamed the capital of the new Nunavut territory, changing Frobisher Bay to Iqaluit, and American place names perceived as pejorative or racist - such as squaw - are being eliminated in many states now.

On modern maps, the name "run" is used instead of "stream" or "river" in some places. Though the rationale for this naming is in dispute, it may just reflect a term common in the early 1600's for streams near tidewater. One student of toponomy (the study of place names) has noted:6

- A creek in England typically refers not to a small river at all, but rather a small tidal wash or mud flat. The early colonists of Virginia, who first encountered a vast "tidewater" region, used the word river for large tidal inlets, and creek for smaller tidal inlets. As they explored inland, the terms stuck and were applied to streams.

The most famous of the "runs" is in Prince William County. The first major land battle of the Civil War was fought at the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861 - at least that is the name used by the Union side of the conflict. The Confederate side usually named battles after towns rather than streams, referring to the Battle of Manassas instead of the Battle of Bull Run. The National Park Service signs at Manassas National Battlefield Park reflect the Southern perspective.

Occoquan Creek (as labelled on Route 234, in 2014)

the Little River in Russell County

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Richlands 7.5 x 7.x topographic quadrangle map (2013)

Links

References

1. "Mantle - A Tribute to Virginia s Tribes," Virginia Indian Memorial Commission, http://indiantribute.virginia.gov/documents/2015_03_16-Final-Design-Presentation.pdf (last checked March 9, 2018)

2. "A New Description of Carolina," North Carolina Maps, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/114; William Strachey, The Historie of Travaile Into Virginia Britinia, Hakluyt Society, 1849 , p.34, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Historie_of_Travaile_Into_Virginia_B.html?id=fYYMAAAAIAAJ (last checked March 6, 2016)

3. Durand de Dauphine, A Huguenot Exile in Virginia, or Voyages of a Frenchman exiled for his Religion with a description of Virginia and Maryland, (Gilbert Chinard, editor), The Press of the Pioneers, New York, 1934, p. 105, p.107

4. "What's in a Name? | Elizabeth River," The Virginian-Pilot, December 24, 2012, http://pilotonline.com/news/local/what-s-in-a-name-elizabeth-river/article_796e424f-7c8b-53bf-ab84-fa6764c667b4.html (last checked March 6, 2016)

5. Earnie Porta, Occoquan, Arcadia Publishing, 2010, p.15, http://books.google.com/books?id=RjkNEcJJ4k8C (last checked January 15, 2015)

6. "Lorton History - One Woman's Campaign," Lorton Patch, January 25, 2011, http://lorton.patch.com/groups/around-town/p/one-womans-campaign (last checked January 15, 2015)

7. Fly, Paul, "Mapping Toponomy," http://web.archive.org/web/20060708194402/pfly.net/?p=26 (last checked January 15, 2015)

8. "Geographic Names Information System," US Geological Survey, http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic (last checked January 15, 2015)

the Native American name for the Chickahominy River was not supplanted by the colonists's name to honor Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southampton and a leader in the Virginia Company - though he may have been the source for the name Hampton Roads

Source: John Carter Brown Library, A mapp of Virginia discouered to ye Falls, and in it's Latt: From 35 deg: & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg: bounds of new England (by John Farrer in 1651)

Rivers of Virginia

Virginia Places