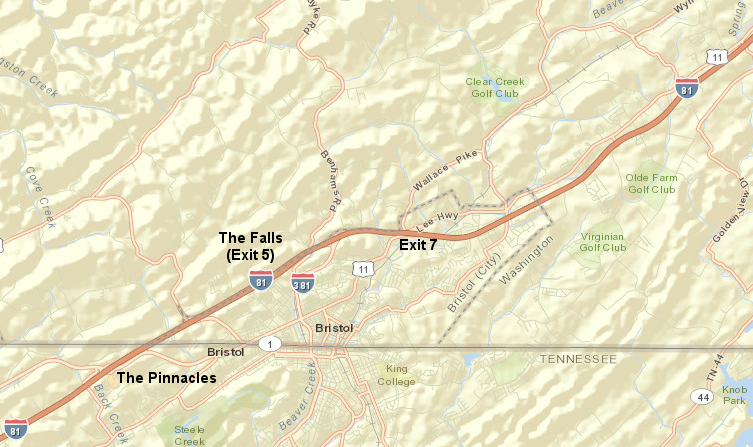

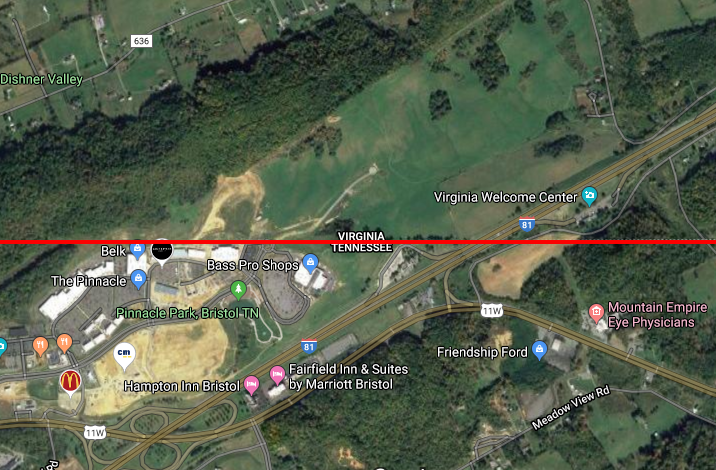

proposed new commercial development near Bristol is concentrated on I-81 exits, not downtown... and jurisdictions compete for tax revenues

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

proposed new commercial development near Bristol is concentrated on I-81 exits, not downtown... and jurisdictions compete for tax revenues

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The City of Bristol is an independent political jurisdiction, separate from Washington County in Virginia.

In 2013, the city of Bristol and Washington County threatened lawsuits over the city's plans for commercial development at Exit 5 on I-81. The city purchased 140 acres to create "The Falls" project, with over one million total square feet of mixed use commercial/retail/motel development. The Falls was financed in part with $25 million in general obligation bonds borrowed by the city (and later by additional revenue bonds). It was designed to attract a new Cabela's sporting goods store, a Sheetz convenience store, and various restaurants.

Bristol could invest up to $40 million to develop "The Falls" because Virginia's General Assembly had passed a law in 2012 to allow jurisdictions to retain the State of Virginia's portion of sales tax revenues from a development of regional impact. The Falls had to create 2,000 jobs, generate $5 million in new annual tax revenues, and attract 1 million visitors a year in order for the city of Bristol to use the sales tax revenue that normally would go to the state.14

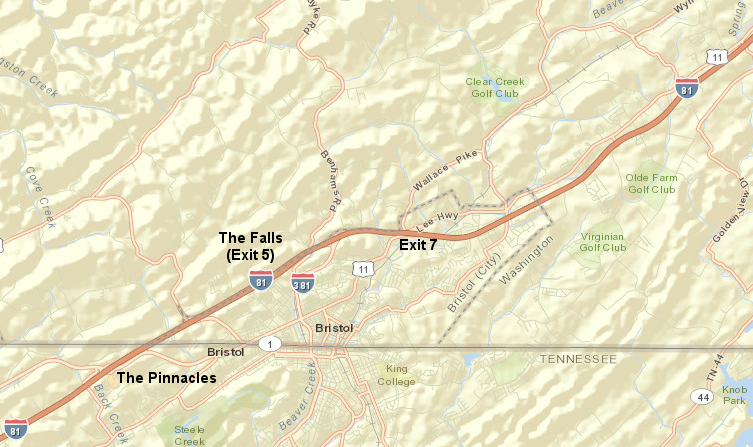

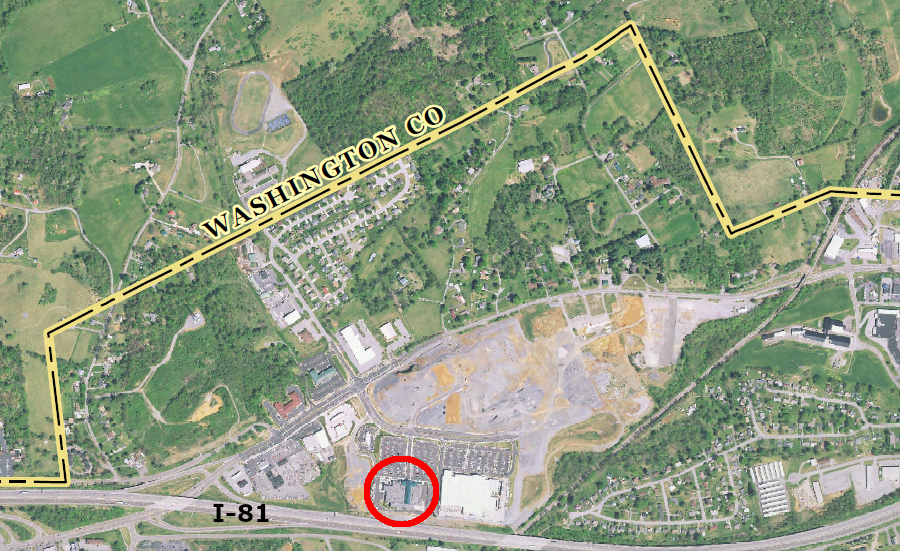

Bristol, Virginia used public funds to convert a limestone quarry at Exit 5 into a retail complex named The Falls

Source: Google Earth (2008)

Normally, a project with such regional economic impact would have political support from all nearby jurisdictions, because benefits would spill over boundaries as 2,000 workers spent their earnings. Washington County was specifically concerned that a Lowe's home improvement warehouse located at Exit 7 in the county would move two miles down the interstate to Exit 5, in order to open a larger store and attract additional customers coming to "The Falls." The political complication: the special state law that allowed Bristol to retain state sales taxes would facilitate a move by Lowe's (and then perhaps Walmart and Sam's Club at Exit 7) from Washington County into the City of Bristol.

If sales and property taxes associated with Lowe's shifted from Washington County to the city, then Bristol rather than Washington County would receive the local 1% of the sales tax generated by that store. Washington County Board of Supervisors would need to raise their property tax rate by a penny ($0.01/$100) in order to maintain the tax revenues required for schools, fire/police, and other public services in the county. County property taxes in 2012 were $0.63 per $100 of fair market value, so the loss of one store would force the seven elected county supervisors to raise taxes by 1.5% or cut county services - never an attractive choice for elected officials.

If Walmart and Sam's Club, as well as Lowes, migrated from Exit 7 in Washington County to Exit 5 in the City of Bristol, the county would lose over 70% of its annual sales tax revenue. To resolve the dispute, Bristol agreed to pay the county the lost taxes (up to $350,000/year) for seven years after Lowe's moved. The city also agreed to compensate the county so boundary-shifting moves by large retailers in the next 15 years would be revenue-neutral, and the county agreed to share tax revenue from future development on a parcel that was next to the city-county border at Exit 7.2

The Lowes building was purchased by Rural King, a farm and home store. It could not start business there for five years, due to non-compete restrictions with Lowe's. When it did prepare to open in 2020, Rural King requested Washington County provide it a rebate of 50% of the projected local sales tax revenues. County officials debated the percentage, and city officials also paid attention. For the remaining two years of the city-county deal regarding owe's, sales tax revenues coming from Rural King would reduce the payments that Bristol was required to make to Washington County.3

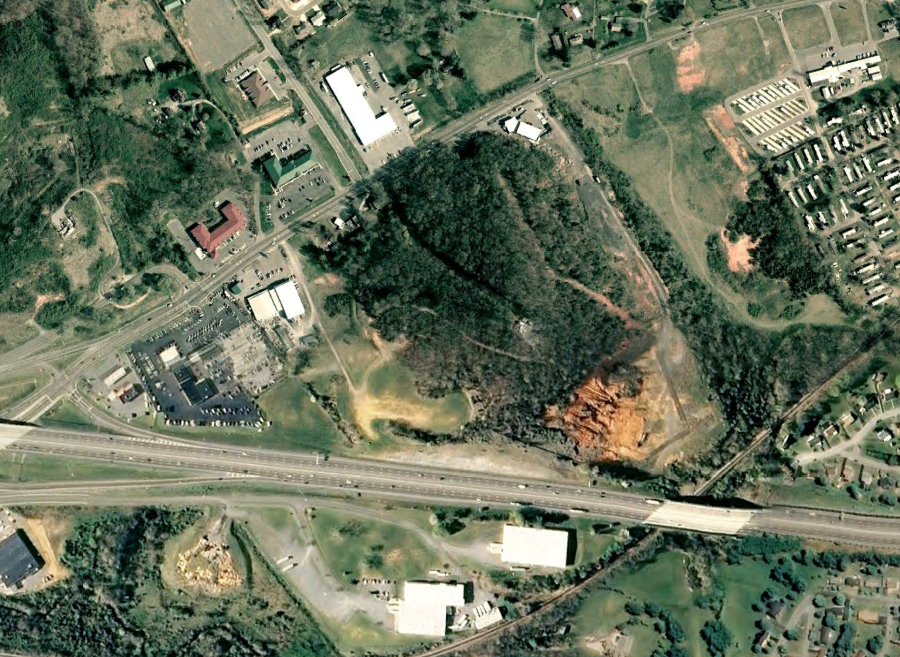

The Falls, before completion of Lowe's and Cabela's

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The conflict between city/county was mirrored by competition between the states; Washington County competes with both Bristol, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee. Tennessee passed the Border Region Retail Tourism Development District Act in 2011. New retail projects that attracted an investment of at least $20 million within 12 miles of a state border and near an interstate highway were granted over 4% of the additional sales tax revenues they generated. The city of Kingsport proposed the idea but never attracted an investment which qualified. East Ridge, on the Georgia border, qualified after Bass Pro Shops agreed to build a $25 million store.

The city of Bristol, Tennessee sold $25 million in bonds to finance the 250-acre Pinnacles development in Tennessee. That commercial development, south of the state line at Exit 74 on I-81, was anchored by Bass Pro Shops. Its competitor, Cabela's, chose to become an anchor store at The Falls. Both Bass Pro Shops and Cabela's used competition between government jurisdictions to get subsidies for their private companies.4

Lobbyists for the Pinnacles project in Tennessee attempted at the 2014 Virginia General Assembly to block legislation that would facilitate financing the rival project, The Falls at Exit 5 in Washington County. In response, the Bristol, Virginia City Council passed a resolution to official complain to its counterpart in Tennessee about the "unwarranted aggression," saying:5

The Falls was expected to generate tax revenues for Bristol, but instead became a drain on the city's finances. By 2019, between the debt for a city-financed landfill project and the debt for The Falls, Bristol owed over $100 million. The city's annual budget was just $55 million. That caused city officials in 2019 to support a proposed gambling casino and also a medical marijuana facility, both proposed for the empty Bristol Mall.

Local legislators in the General Assembly reversed their previous opposition to casino gambling, despite the traditional conservative values prevalent in the region. The Bristol city manager, well aware of the city's stressed financial condition, stated:6

The first Cabela's in Virginia opened as a Phase I anchor store at The Falls, along with Lowe's, in 2015. They were followed by a Sheetz gas station and a Zaxby's restaurant. Full build-out of the 120-acre complex would create 1 million square feet of retail space, but the timing for the project was challenging. Brick-and-mortar shopping stores were competing with online sales from companies such as Amazon. The Bristol Mall closed in 2017, as the J. C. Penney and Belk stores folded.

Advertising to recruit new businesses to The Falls highlighted the site's proximity to I-81 and the potential to attract customers from Tennessee, which had a 9.75% sales tax compared to 5.3% in Bristol:7

The city had sold $47 million in general obligation bonds and $33 million in revenue bonds to convert the old limestone quarry at Exit 5 into The Falls, but the retail complex failed to attract the anticipated $260 million in new development. The Cabela's closed in 2020, and was consolidated with the company's similar Bass Pro Shops store at The Pinnacle complex in Tennessee. The city had invested $17 million from the sale of revenue bonds to build that 85,000 square foot store for Cabela's.

The shift of the sporting goods store to The Pinnacle demonstrated the relative success of that Tennessee site in contrast to The Falls. The Pinnacle had 70 businesses, compared to just 10 at The Falls. Best Buy had already moved from Route 7 to The Pinnacle, and Outback Steakhouse had also moved out of Bristol to The Pinnacle. The retail stores which opened in Phase 1 at The Falls had not generated enough tax revenue to cover repayment costs for the revenue bonds, much less generate enough to start repaying the general obligation bonds.

Bass Pro Shops explained clearly why it consolidated its Cabela's store with the Bass Pro Shop at The Pinnacle:78

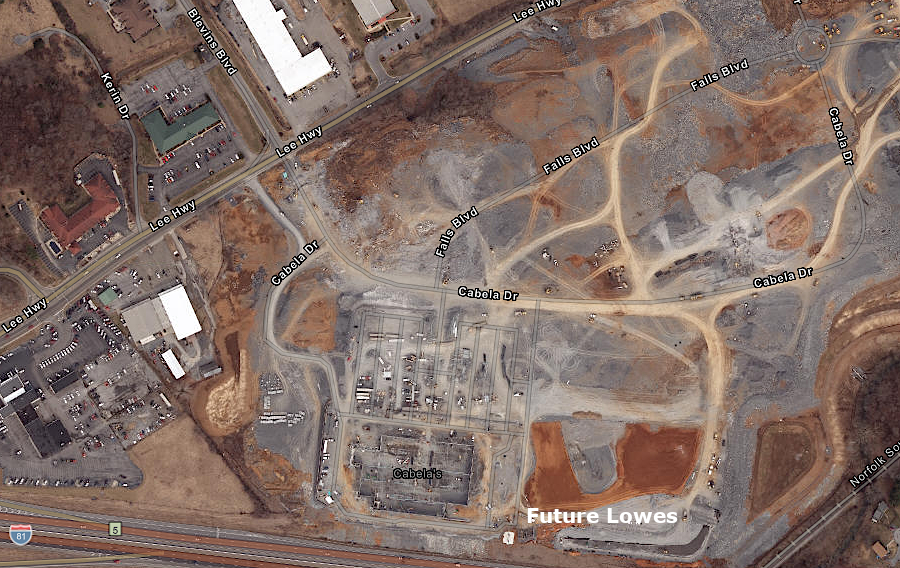

the developer of The Pinnacle, with a Bass Pro Shops store, owned 350 adjacent acres and undeveloped just north of the Virginia-Tennessee line

Source: Google Maps

In February 2020, as the Virginia General Assembly was approving legislation to allow casino gambling within the Bristol city limits, the developer of The Pinnacle claimed that he had made the initial proposal for such a gambling facility in 2017. He had proposed to place it in Washington County, on 350 acres adjacent to The Pinnacle but across the state line in Virginia.

When he also warned the city manager for Bristol, Virginia that Cabela's would close, they discussed locating the casino at The Falls in the soon-to-be-vacated Cabela's building. However, it was too small for the casino/hotel/resort complex envisioned. The developer suggested Bristol and Washington County create a revenue sharing agreement to facilitate development of the casino on the vacant land next to The Pinnacle.

when Cabela's (red circle) closed in 2020, The Falls was mostly undeveloped land without Phase I completed

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Wallace VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle

Instead, the city worked with rival developers and got the Virginia General Assembly in 2019 to propose authorizing a casino only within the city limits of Bristol. Before final approval of a casino gambling bill, the Pinnacle developer announced an agreement with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to build a full-scale casino on the property adjacent to The Pinnacle. The Cherokee already operated two successful casinos in North Carolina, based on their tribal gaming rights and developed under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

The Pinnacle developer was surprised that the General Assembly moved so quickly to authorize casinos. The Bristol team had announced a deal for casino operations with Hard Rock International before he completed negotiations with the Cherokee, and claimed he was mimicking their original idea of a casino/resort in the area. According to the Bristol Herald Courier, the Bristol (Virginia) city manager had been proposing a casino since 2014, but always within the boundaries of the city so it would receive the tax revenue.

State Senator Louise Lucas (D-Portsmouth) had advocated for casino cambling since she was elected in 1991, to generate more revenue for her economically-distressed city. She made clear to representatives of The Pinnacle that she was not going to support any facility outside of Bristol, and that the five cities who had pushed for casino authorizations were "welded at the hip" in mutual support.

Frustration at being unable to get the Virginia legislators to authorize competitive casino proposals at Bristol, as recommended in a 2019 study by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), led the Pinnacle developer to reveal publicly his perception of a politically-tainted decision process:9

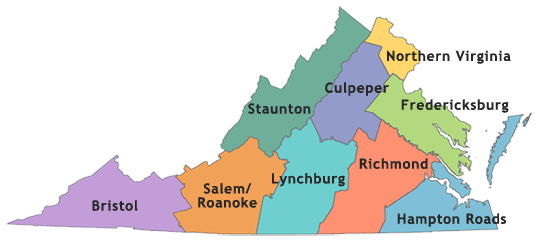

The 2020 General Assembly authorized referendums for casino gambling in five cities, but imposed a unique requirement on Bristol. It was required to share gaming tax revenues with 12 nearby counties of Bland, Buchanan, Dickenson, Grayson, Lee, Russell, Scott, Smyth, Tazewell, Washington, Wise and Wythe, which were all members of the regional Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Bristol District. The jurisdictions were directed to create a Regional Improvement Commission to allocate the money.10

The revenue sharing provision was key to generating support in the General Assembly for approving a casino in Bristol. One local member of the House of Delegates was blunt about how the nearby counties feared Bristol would thrive and they would barely survive, if the casino's gaming tax revenue benefitted only the city:11

Though Bristol quickly took advantage of the ability to open a casino and start generating tax revenue, the city's Industrial Development Authority still paid only 55% of the amount due on May 1, 2022 for the Series B revenue bonds issued in 2014. The city had exhausted the debt service reserve fund, in part because Bristol had committed to pay some of the annual tax revenues to attract Lowes to move to The Falls. The partial payment on May 1 was short by $383,500.

The repayment obligation for the Series B bonds was tied to revenue generated just by Phase 1 of the project. Repayment for Phase 2 and Phase 3 was backed by the full faith and credit of the city, which had issued separate Series A general obligation bonds.

The distinction between revenue vs. general obligation bonds was significant. Bristol officials claimed the partial default would not affect the city's credit rating, which Moody's had just upgraded.12

Bristol was required to share revenues from a new casino with 12 counties in the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Bristol District

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Park and Ride Lots