in the 1800's, only a few Virginia roads such as the Valley Turnpike had a rock surface that was good enough to allow travel after a rain (and thus worth the cost of a toll)

Source: National Park Service, The Valley Turnpike Company

in the 1800's, only a few Virginia roads such as the Valley Turnpike had a rock surface that was good enough to allow travel after a rain (and thus worth the cost of a toll)

Source: National Park Service, The Valley Turnpike Company

In 1817, the Virginia General Assembly issued the first charter to incorporate a company to build a turnpike for the 68 miles between Wincheter-Harrisonburg on the historic path of the Great Wagon Road. That project failed, but the legislature had better success after it chartered the Valley Turnpike Company on March 3, 1834. The charter allowed the company to convert the 68-mile path between Winchester and Harrisonburg into an upgraded road, and to charge tolls to pay for the cost of the upgrades.

In 1837, the state issued a second charter to the Harrisonburg and Staunton Turnpike Company for improving the road another 25 miles south of Harrisonburg to Staunton. The two companies quickly merged to manage the 93 miles of turnpike as a toll road. The Board of Public Works bought 40% of the bonds, and valley residents bought the other 60% required to fund the project.

The state imposed standards in the charter. The macadamized portion of the turnpike, with a rock surface, was supposed to be a minimum of 18 feet wide. Maximum grade, the slope up which horses and mules had to haul carts, was limited to 3%.

Construction was completed in 1840. The company established tollgates every five miles, so the users of the road funded ongoing maintenance. Toll revenues also repaid the people and Bureau of Public Works who had purchased the bonds, including interest.1

The state agreed to purchase 40% of the stock. Residents in the counties which would benefit, Frederick, Shenandoah, Rockingham and Augusta, bought most of the 60% of stock sold to the public. Baltimore investors also helped to finance the Valley Turnpike. It was expected to be a profitable investment, and the improved road would direct trade towards Baltimore rather than Alexandria.

Construction consisted of upgrading the Great Wagon Road, the dirt trail used since the 1720's by emigrants crossing into Virginia via the Cumberland and Hagerstown valleys west of the Blue Ridge. Covered ridges and rock-lined culverts were built to cross streams, in order to minimize the number of steep grades on either side of the fords. The flatter turnpike made it easier for horses, mules, and oxen to haul wagons loaded with more wheat.

The turnpike was supposed to be two lanes wide. That width would allow wagons to pass in opposite directions, without a debate over who had the right-of-way and who had to pause. In reality, in many places it was so narrow that customers complained about the delays required for just one wagon to travel at a time. In an era where only black powder and human muscle was used for blasting rock, leaving some narrow stretches was key to minimizing construction costs.

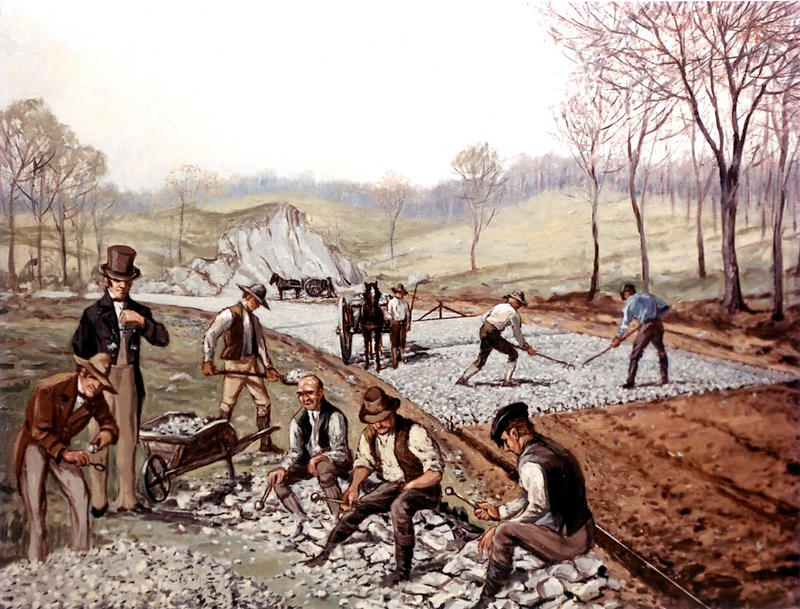

The dirt base of the Great Wagon Road was "macadamized" by adding three layers of crushed rock, and digging drainage ditches on the side to carry off the stormwater.

worker using a round headed hammer to break limestone into the proper sized road metal in order to maintain a section of the Valley Pike

Source: National Park Service, Vital Route

The bottom layers of crushed rock were 8" deep, using chunks about 3" in diameter to form a solid base. The surface layer used rocks crushed to no more than 1" in diameter, laid 2" thick. The rock came from the nearest outcrop of limestone or shale.

Livestock found the sharp edges of the crushed rock surface to be uncomfortable. When cattle were driven north to Philadelphia or Baltimore, the Shenandoh Valley cowboys often preferred to use the parallel dirt roads west of the turnpike.

the Valley Turnpike was a toll road, improving the Great Wagon Road by smoothing grades and creating a hard (macadamized) rock surface

Source: Federal Highway Administration, 1823 - First American Macadam Road (painting by Carl Rakeman)

The toll to travel the entire length of the Valley Turnpike before the Civil War were about $100 in current dollars. Farmers were willing to pay tolls every five miles, because the road's hard-surfaced road and gentle grades substantially reduced the time required by alternative free routes to haul crops to market:2

in 1922, the Valley Pike was a macadamized road

Source: Library of Congress, Valley Pike - Shanandoah Valley (1922)

Building a macadamized toll road was not a new concept when the Valley Turnpke was chartered. The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road was the first broken-stone and gravel surface built in America, back in 1795. The first stretch to use John Louden McAdam's principles of a thick layered base, with a surface of smaller rocks, was built between Hagerstown and Boonsboro, Maryland in 1823. In 1830, the entire 73-mile long National Pike between Cumberland, Maryland and Wheeling, Virginia was macadamized.3

The paved Valley Turnpike surface supported heavy wagons, but continued maintenance was required. Unlike modern roads, there was no petroleum-based tar available to glue the rocks together and make an impervious surface. McAdam developed his technique to pave roads long before asphalt was available, using stone dust as the binder for the smaller rocks on the surface layer. Rain, hoofprints, and wagon wheels cut pits and ruts that require constant repair.4

stagecoaches pulled by teams of horses stopped at ordinaries along the Valley Turnpike

Source: US Department of Transportation, 1795 - The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road (painting by Carl Rakeman)

The heaviest loads ever carried on the Valley Turnpike were locomotive engines. They were needed in 1862 by Southern railroads, which could no longer purchase new equipment from Northern manufacturers during the Civil War. Confederate forces removed them from the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad shops at Martinsburg.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was loyal to the Federal government, so its locomotives were captured property. Seizing them was relatively easy; getting them to a railroad under Confederate control was a harder challenge.

In 1862, there were no railroad tracks leading south of Martinsburg. Even if the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad locomotives could have been brought to the Winchester and Potomac Railroad at Harpers Ferry, its trestles and strap rail track were too flimsy to support moving the heavy engines south to Winchester. The locomotives used on the Winchester and Potomac Railroad were much lighter pieces of equipment.

The solution was to partially disasembled the locomotives to reduce their weight, then hook the front of each one onto large wagon wheels. Teams of up to 40 horses, lined up in ten rows with four horses each, then pulled the heavy loads miles up the Valley Turnpike to the Confederate-controlled Manassas Gap Railroad track at Strasburg. The wheels would, at times, cut through the macadam surface of the Turnpike. Jackscrews were then placed under the locomotives, and when they were lifted high enough rocks would be placed underneath to reinforce the turnpike's surface and permit further movement towards Strasburg.

The Confederates lost control of the Manassas Gap Railroad before all the locomotives could be brought by that line to Richmond. At least one engine was hauled by horses and strong men all the way via the turnpike to Staunton, where it was placed on the Virginia Central Railroad. 5

both Union and Confederate armies marched along the Valley Turnpike during the Civil War

Source: Federal Highway Administration, 1840 - Shnandoah Valley Turnpike (painting by Carl Rakeman)

At the end of the Civil War, the Valley Turnpike remained in business. It was one of the few projects in which the Bureau of Public Works recovered its investment.

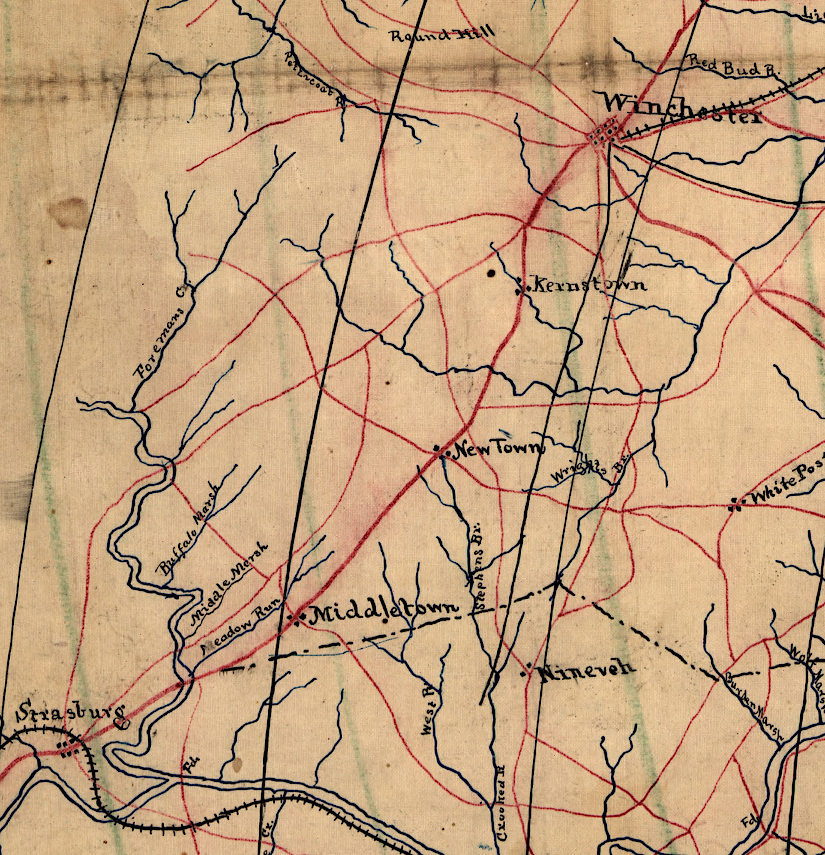

the Valley Turnpike had no competition from railroads between Winchester-Strasburg until after the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of portions of Virginia and Maryland, extending from Baltimore to Strasburg (186__)

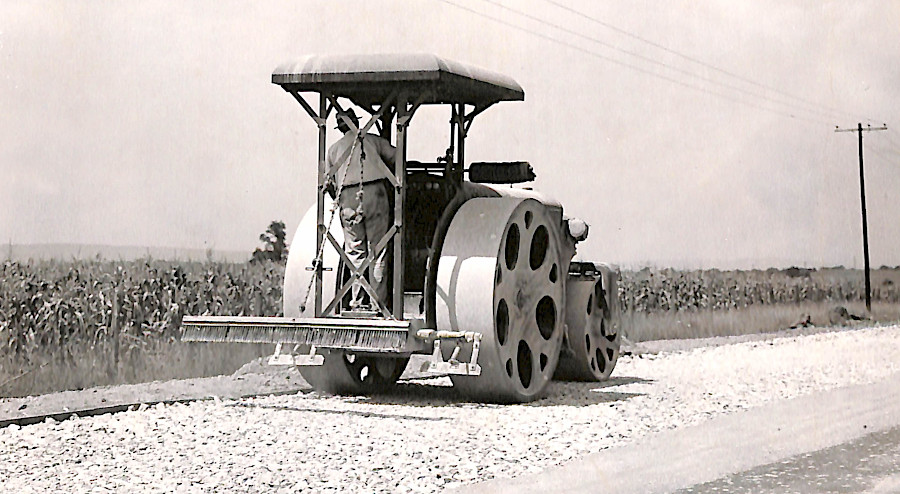

It collected tolls until August 31, 1918, when the costs to maintain the surface for automobile traffic was too great. The turnpike was given to the state, which used the newly-passed gas tax (rather than tolls) to maintain the highway. In the Depression, Virginia substantially rebuilt the road, creating Highway 11.6

paving US 11 (former Valley Turnpike) in 1937

Source: National Archives, Roller on Macadam on U.S. 11 North of Winchester, Virginia