Harry Byrd (shown here when governor in 1929) never graduated from high school

Source: University of Houston Digital Library, Harry F. Byrd, Governor of Virginia, Master of Ceremonies at launching of USS Houston (CA-30)

Harry Byrd (shown here when governor in 1929) never graduated from high school

Source: University of Houston Digital Library, Harry F. Byrd, Governor of Virginia, Master of Ceremonies at launching of USS Houston (CA-30)

V.O. Key sadly described Virginia government after World War II as a "museum of democracy" housing all the symbols of government by the people, but none of the substance. One man is typically credited with creating that situation.

Harry Byrd led a political organization that controlled Virginia politics for 50 years. His "nod" was considered essential before a candidate could expect to win a race for governor, and his "golden silence" (rather than endorsement of Democrats running for President) encouraged Virginia Democrats to vote for Republican candidates every four years.1

Personally, Byrd was never a dictator, and did not gain great personal wealth at the public's expense. Traditionally, the Virginia way was to resolve political and economic conflicts in a genteel manner.

Demagoguery and criminality were not unknown, but the Byrd Organization was as vague as it was effective. Byrd described his political base not as a machine, but as "a loose organization of friends, who believe in the same principals of government." "Some people say I run a political machine in Virginia. All I do is offer a little political advice now and then."2

Byrd was successful because he created a voluntary alignment of a homogenous group with common views. He made decisions after carefully ascertaining the feelings of the local officials. The base of the Byrd Organization was a "courthouse clique" in each county, with support from the five constitutional officers (Sheriff, Commonwealth's Attorney, Clerk of the Court, Treasurer, and Commissioner of Revenue).

The 1902 state constitution established the requirement for each county to elect people to those five positions. A few counties have established new administrative forms of government, and in some cases the five constitutional offices have been modified. For example, in Prince William County the county treasurer and commissioner of revenue have been replaced by a Department of Finance reporting to a county executive.

Harry Flood Byrd came to prominence 80 years ago by leading the fight in 1922 against state bonds for new road construction. With the increased popularity of the automobile, all states were challenged by the requirement to improve and pave highways that, traditionally, had been managed locally by the counties. Byrd was a supporter of better transportation - he managed the Valley Turnpike between Winchester and Staunton - and knew cars required better roadbeds than wagon roads of the day.

However, he also knew Virginia had invested heavily in transportation improvements financed in part by the Board of Public Works before the Civil War. The Board of Public Works had been replaced by the State Corporation Commission when the 1902 state constitution was adopted, but the state was still paying off the pre-Civil War debt.

Byrd was also very conscious of the need for fiscal constraint. As publisher of the Winchester Star newspaper, Byrd had brushed close to bankruptcy when the struggling company was unable to pay the supplier of the newsprint. He finally convinced the Antietam Paper Company to sell him newsprint by agreeing to pay daily, as the newsprint was delivered.

Byrd led the opposition in 1922 to the proposal to borrow money to finance the new roads, fearing that once again the state would sacrifice future flexibility by committing too many resources to repaying road construction debt. Byrd was then elected governor in 1925, and institutionalized the "pay-as-you-go" approach where roads were built only as fast as state gas taxes and licenses fees were collected.

Byrd was initially perceived as a "New South progressive." He changed the structure of Virginia's state government through constitutional amendments adopted in 1928, to streamline operations and use tax dollars more effectively. He shortened the ballot, centralizing power under the governor and eliminating separately-elected heads of executive branch agencies. By reducing the number of statewide contests by half to only 5 offices (Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General for state offices, plus two US Senators to serve in the Congress), he reduced the potential of others to develop a political base that might rival the Byrd "organization."

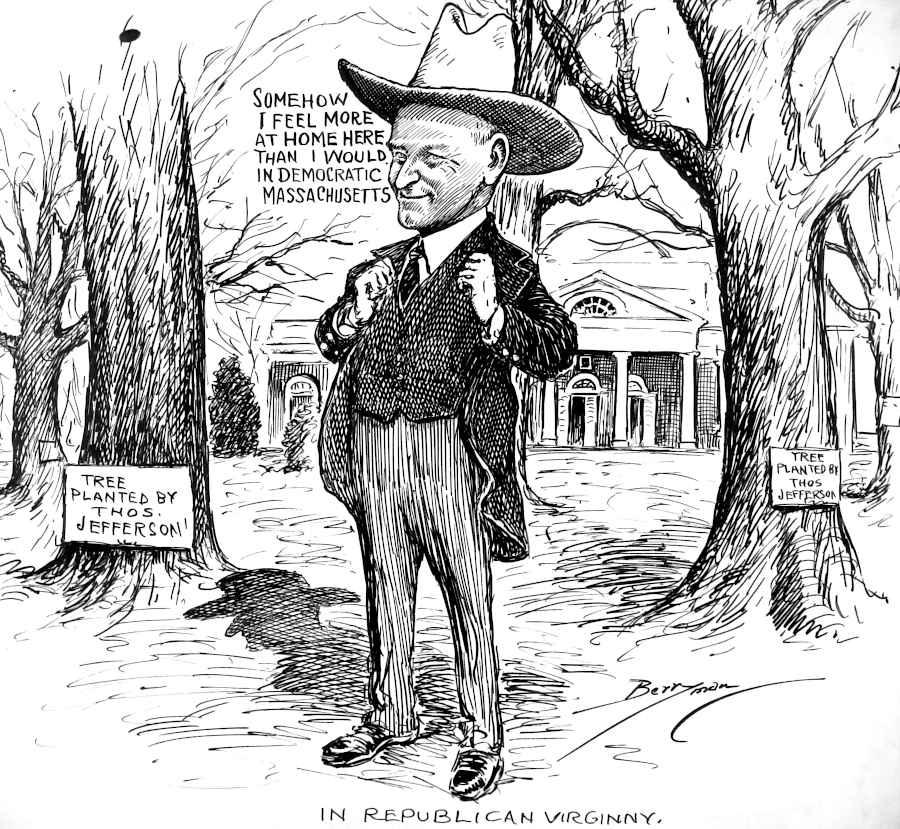

cartoonist Clifford Berryman suggested Calvin Coolidge would enjoy retiring to Virginia after the 1928 presidential election, because Harry Byrd's priorities of low taxes and limited government appealed to Republicans

Source: National Archives, In Republican Virginny (by Clifford Berryman, November 30, 1928)

Byrd chose to use his influence to limit the taxes and make Virginia attractive to businesses who might locate manufacturing facilities in the state.

In his earlier years, Byrd was innovative in his attempts to provide services while keeping taxes low, especially for his rural supporters. Later, it became very clear that Byrd was willing to accept limited services far below what other states offered their citizens in order to maintain a low tax rate. He was even willing to close down the public school system to retain the segregated social system of the past.

In his earlier years, Byrd was innovative in his attempts to provide services while keeping taxes low, especially for his rural supporters. Later, it became very clear that Byrd was willing to accept limited services far below what other states offered their citizens in order to maintain a low tax rate. He was even willing to close down the public school system to retain the segregated social system of the past.

When it became clear that the funding for road improvements was not sufficient to "get Virginia out of the mud," especially in the Depression. Byrd arranged for the state to assume responsibility for maintaining county roads in the "Byrd Road Law" (or Secondary Roads Act ) of 1932.

He also arranged for the counties to have total control over their property tax rates, eliminating the pattern where the state imposed a property tax as well as an income tax. In exchange for allocating 100% of the real and personal property taxes to the counties and cities, Byrd arranged for the state to receive 100% of the income tax. The trade meant that rural farmers could ensure property taxes for school support would stay low. If urban voters wanted higher taxes to pay for better local schools, they would have to tax their own property within the city boundaries.

Byrd, who never graduated from high school himself, recognized that his rural constituency was less interested in state-supplied services than they were in low taxes. Public schools were expensive, and the urban residents were far more supportive of state funding for schools than were the farmers.

In the mid-1900's, Virginia farmers needed a large supply of unskilled labor. The level of education required to operate farm machinery at that time was low - and it was perceived to be counterproductive to provide a good education to the rural blacks. They might move to the cities to get a semi-skilled job, rather than stay in the local community where they could be hired seasonally (for low wages...) to plant and harvest crops. The focus on support for rural areas led to a common saying in the General Assembly:3

Virginia was part of the Solid South, where people would rather vote for a "yellow dog" than a Republican associated with the party of Abe Lincoln, but in fact very few people voted at all.

Perhaps the Byrd Organization was relatively honest when it came to graft, in contrast to other political machines at mid-century, but it controlled the vote as tightly as the corrupt machines or the Virginia gentry in colonial days. The limitations on voting in the 1700's were designed to prevent the indentured servants working for one large landowner from voting as a bloc, which would enable one member of the gentry to obtain excessive control at the expense of others. By requiring that men had to own a certain amount of land or a house in town, the restrictions on the right to vote helped ensure that colonial elections in Virginia were decided by those who were economically independent enough to make up their own minds.

After the Civil War, Conservative Democrats coalesced and finally defeated William Mahone, breaking up the alliance of blacks and Readjusters (who sought to increase services at the expense of readjusting the terms for repaying the pre-war state debt, incurred primarily for transportation projects). In the late 1880's, John Barbour led the first Conservative Democrat machine.

Thomas Staples Martin took over after Barbour died, but Senator Martin's political control was thin by the time he died in office in 1919. Byrd's dynamic leadership on the road bond issue led to his taking control and getting elected as governor in 1925, but his ability to shape the political landscape across the state was based on the fact that it required very few votes to win a contest in Virginia.

The 1902 Constitution had disenfranchised most black and poor white voters, by requiring voters to pay the poll tax before they could cast a ballot. In 1905, the number of people voting was reduced to 50% of the number who voted in 1901. In 1940, only 10% of the Virginians over the age of 21 were voting. The percentage of blacks over 21 who voted was about half of that.4

plowing corn in Arlington County (note Washington Monument in background)

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Popcorn: Ingrained in America's Agricultural History

In addition to eliminating the opposition voters in 1902, Martin's organization also had to ensure that the right voters appeared at the polls and were allowed to vote. The courthouse crowd knew who were their reliable supporters in the county, and ensured that the poll taxes for those individuals were paid on schedule for the three years in advance of an election.

The General Assembly chose the circuit court judges who appointed the local Electoral Boards, who appointed election judges that ruled on whether individuals were entitled to vote. With such a limited electorate, the opposition occasionally threatened the power of the machine when a "hot topic" spurred an increase in the number of voters, or the Organization split its support between two candidates.

In many sections of Virginia, the Republican opposition was feeble, just sufficient to qualify individuals for appointment to Federal patronage positions when the President was a Republican. Winning the Democratic primary was tantamount to winning the election. With control of the election machinery, the Byrd Organization did not have to adopt the techniques of overtly-corrupt urban machines where people voted "early and often" and dead people were kept on the voting rolls to help stuff the ballot box.

Nonetheless, fraud did occur. Absentee ballots in Southwest Virginia were commonly collected in advance, and occasionally counted after Election Day in order to ensure victory. Usually the fraud was perpetuated by the Democrats against the Republicans, or occasionally vice-versa, but there was also blatant fraud within the Democratic primaries.

In the 1945 primary for Lieutenant Governor, Charles Fenwick (for whom George Mason University's main library was named) was defeated only after a judge threw out the votes from Wise County. The vote totals said Fenwick had received 3,307 votes, while his opponents received only 122. When the results were challenged, the Wise County clerk claimed someone had stolen the poll books that recorded who had voted. After the county's votes were thrown out, Fenwick's 572-vote victory became a defeat.5

The Organization's control as not complete, however. Anti-Organization candidates were elected to the General Assembly from the cities, where social services were limited by the low tax policies. In Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, after the military buildup in World War II, a greater percentage of the residents were not native Virginians willing to be apathetic about state government. Also, the Fighting Ninth Congressional District in Southwest Virginia retained a strong two-party tradition, reflecting the strength of the United Mine Workers union in the coal fields and the railroad unions.

Harry Byrd built a political machine that dominated politics in Virginia for four decades

Source: Library of Virginia, Harry Flood Byrd

The Byrd Organization ensured that rural residents received excessive representation in the General Assembly. An excessive number of delegates and state senators were elected from rural districts, giving conservatives an "unfair" advantage. Unbalanced representation was as old as democracy in Virginia. The 1830-31 and 1850 conventions failed to resolve the concerns of the western counties, leading to their formation of an independent state in 1863.

The urban population growth was not reflected in the makeup of the General Assembly until the Supreme Court imposed the "one person - one vote" requirement for redistricting in the 1960's.

Few Virginians belonged to labor unions during the heyday of the Byrd Organization, when manufacturing was a small part of the state's economy. The few union members worked primarily in textile factories, coal mines, railroads, shipyards, and utilities. Their influence was noticeable in the urban centers and Southwest Virginia, but statewide their impact was marginal. A 5-month strike by the United Textile Workers against the Dan River Cotton Mills in 1930-31 soured public opinion without forcing the company to meet the workers' demands.

Nonetheless, the conservatives in the Byrd Organization constantly raised fears that the American Federation of Labor (AFL) or the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) would take control of the state if anti-organization candidates were elected. After World War II, strikes for higher wages and better working conditions, together with Red-baiting by the politicians and media to demonize the union leaders as Communists or dupes, caused respect for organized labor in Virginia to sink to a new low.

When the Seafarers International Union called a strike against the Chesapeake Ferry Company in 1946, the state seized the company. To block unions, the state made ferry service in Hampton Roads a government service provided by the Virginia Department of Highways, until constructing tunnels and bridges to replace the ferries.

Later in 1946, employees of the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO) planned to join a national strike by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW). The utility provided electrical power to half the state, and Governor Tuck announced he would seize the power plants and draft VEPCO's workers into the land and naval forces of Virginia. During peacetime, the governor could not force civilians into the Virginia State Guard or the "unorganized militia" that had been authorized during the 1780's - but the IBEW settled before the bold approach of Governor Tuck was fully tested in the courts.

When the United Mine Workers went on strike that same year, the state imposed coal rationing. Rationing was a familiar process to those who had lived through World War II, but was not popular. The General Assembly passed a statewide right-to-work law in 1947, several months before the US Congress passed the Taft-Hartley law confirming the state's right to make the closed union shop illegal in Virginia.

The result of the straightforward opposition to union demands was a dramatic increase in the public's respect for the governor and of the Byrd Organization's "courageous" response to the VEPCO strike. The fight with the United Mine Workers union stimulated conservative rural farmers to vote for the Organization's candidates.

The Byrd Organization's resistance to unions illustrated most clearly how the national Democratic Party had diverged from the Byrd Organization's concept of "Democrat." Byrd himself had initially considered Harry Truman as a welcome replacement for President Roosevelt. Byrd thought of Truman as a fellow Southerner, less inclined to support liberal policies.

The Byrd Organization's resistance to unions illustrated most clearly how the national Democratic Party had diverged from the Byrd Organization's concept of "Democrat." Byrd himself had initially considered Harry Truman as a welcome replacement for President Roosevelt. Byrd thought of Truman as a fellow Southerner, less inclined to support liberal policies.

Soon, it was clear that Truman was choosing to support civil rights and labor unions. Byrd was unwilling to support him for election in 1948, even through Truman was the nominee of the Democratic Party for president. Byrd's disappointment with FDR had spread to the national Democratic Party. Abraham Lincoln may have been the first Republican president, and the Republican Party may have imposed Reconstruction on the South after the Civil War, and the former Confederate states may have formed a "solid south" of support for Democrats based on that history... but once Franklin D. Roosevelt and other national Democratic candidates began to court urban voters and veered away traditional support for segregation and low taxes, Byrd split with the party.

Starting in the 1930's, Senator Byrd maintained a "golden silence" when asked who he supported for President. Byrd successfully steered voters to support Presidential candidates who supported low taxes, balanced budgets, and "state's rights" (especially no Federal interference in Virginia's system of segregating the races). At the national level, that meant Republican candidates for President.

At the state level, Byrd maintained solid control through the Democratic Party into the 1960's. One factor that helped Byrd allow voters to switch to Republican presidential candidates every 4 years, without allowing a competitive Republican Party to develop in Virginia, was the schedule for Virginia elections. Elections for state and local offices were scheduled for odd-numbered years, while races for Congress and President were on even-numbered years. The gap enabled the Byrd Machine to herd the small electorate between parties. Virginia cast its electoral votes for Republican presidential candidates in every election from 1952 to 2004, except in the Lyndon Johnson landslide year of 1964.

Senator Byrd retired from the Senate in 1965. Time Magazine included in his obituary on October 28, 1965:6

Byrd's son was appointed to replace him. Harry Byrd Jr. barely won the Democratic nomination in 1966 to dill out the rest of the term. In 1970, he chose to run as an independent and won re-election.

The election in 1969 of Linwood Holton as governor, running as a Republican, showed the "organization" could no longer suppress the Republican Party at the state level. Holton was elected governor after a bitter Democratic Party primary. The more-conservative William Battle defeated populist Henry Howell. Though he technically endorsed Battle, Howell came close to adopting the "golden silence" approach used by Byrd. Howell encouraged his supporters to be "free spirits," giving them tacit approval to vote for Holton and break the power of the conservatives who controlled the state Democratic Party.

By 1973, many Byrd Democrats had switched to the Republican Party at the state as well as national level.

The realignment of Virginia political parties to match their national counterparts was clear by that year. Mills Godwin won election as governor in 1973 running as a Republican. He delayed his open switch in parties (he had been elected governor as a Democrat in 1965) until opening a dramatic speech, where he brought down the house by saying "Fellow Republicans..."

Harry Byrd Jr. retired in 1976, rather than switch to the now-conservative Virginia Republican Party like Gov. Mills Godwin as the state parties re-aligned to match the national parties.7

In 1976, a 10-foot tall bronze statue of Harry F. Byrd Sr. was placed on the grounds of the state capitol. It honored his service as Governor in 1926-30 and as Senator from 1933-1965, but was also a reminder of his leadership role in Massive Resistance efforts to maintain legal segregation of the races.

In 2020, a Republican member of the House of Delegates proposed the removal of Byrd's statue in a misguided effort to block proposals to move statues of Confederates from public spaces. The move backfired. Democrats in the legislature endorsed the proposal, and only with difficulty was the Republican member able to withdraw his motion. A year later, Democrats introduced their own bill to move Byrd's statue off the Capitol grounds. It passed on a 63-34 vote in the House of Delegates and 36-3 in the State Senate.

Unlike the statues of some Confederate leaders that were removed from Monument Avenue in 2020, no pedestal was left to mark the site of Byrd's statue once it was removed. On July 7, 2021, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported:8

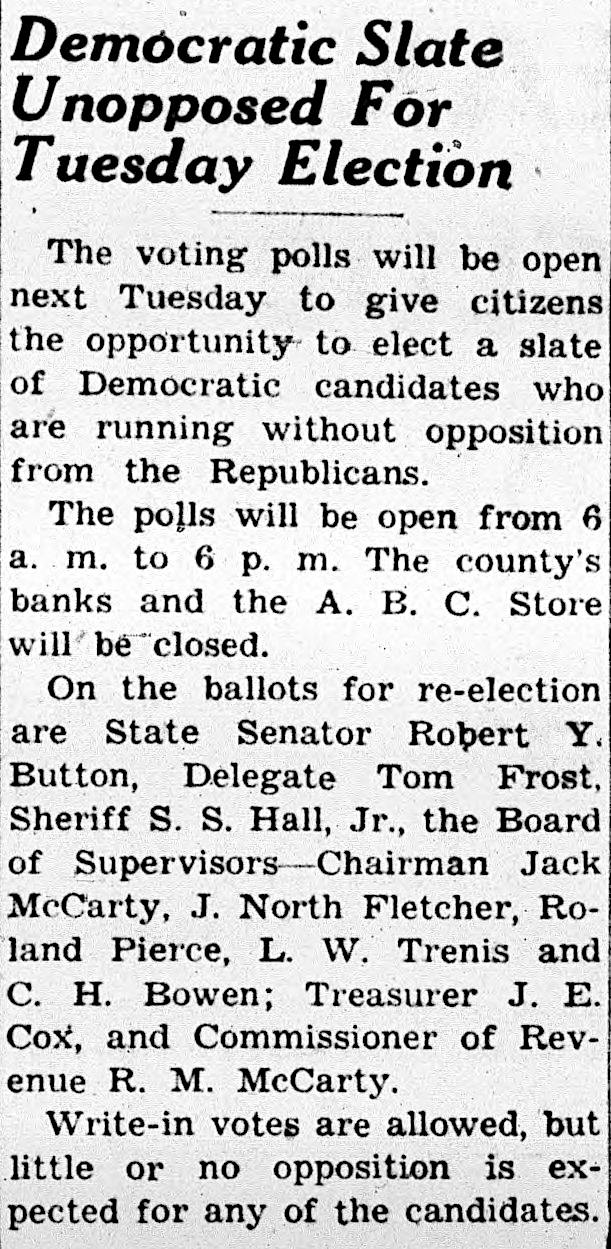

the routine, non-newsworthy power of the Byrd Machine in 1955 was reflected in a news story that was printed on p.7

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Fauquier Democrat (November 3, 1955, p.7)