Bus Rapid Transit in Virginia

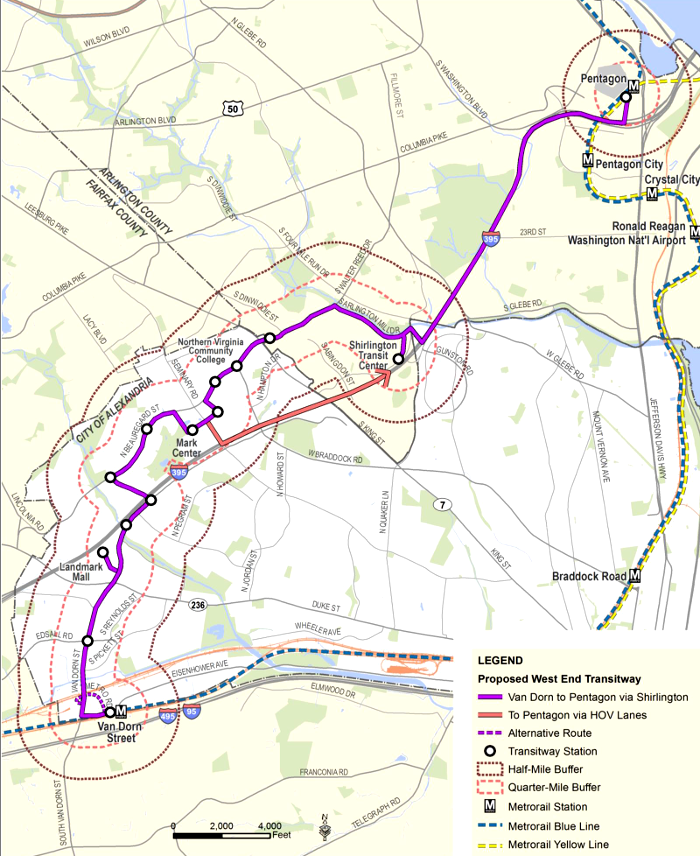

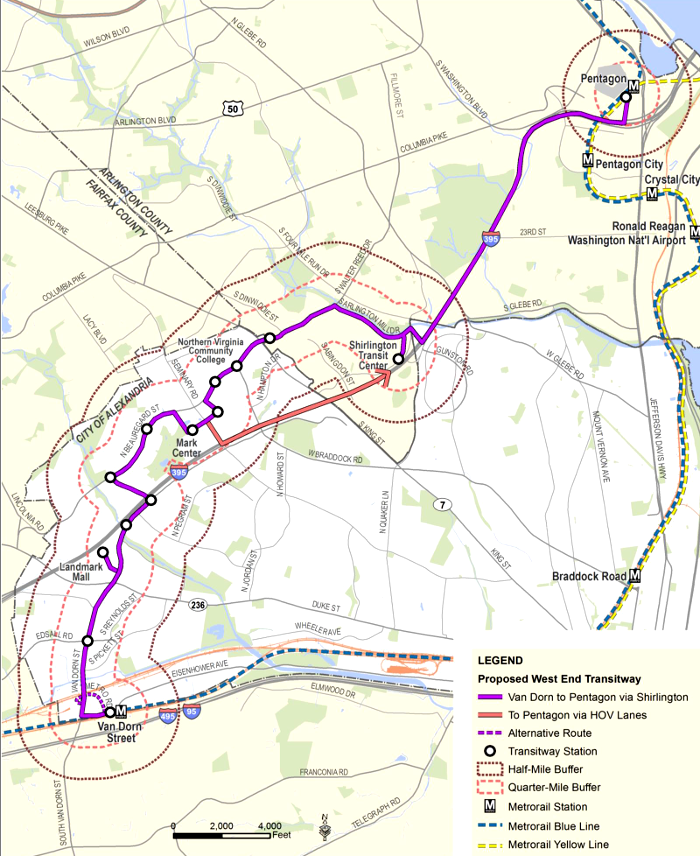

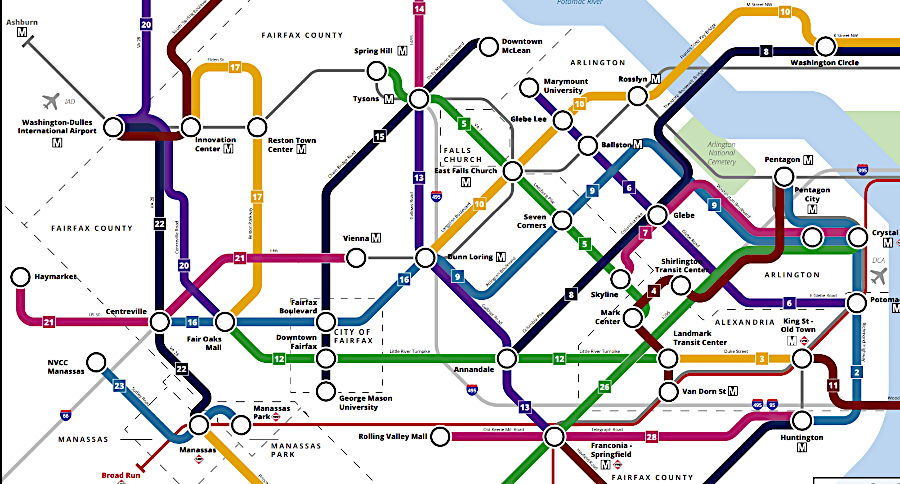

the West End Transitway in Alexandria would use Bus Rapid Transit, as well as shared lanes, to connect Van Dorn Metro Station, Mark Center Transit Center, Shirlington Transit Center, and the Pentagon Transit Center

Source: City of Alexandria, West End Transitway, Draft - Proposed Build Alternative

Railroads transported commuters greater distances, such as Ashland-Richmond and Manassas-District of Columbia. Starting in the 1880's, electricity-powered street car systems stimulated suburban development, allowing workers to live on the edge of cities and commute to work daily.

With the development of automobiles and public funding for paved roads, the suburbs grew dramatically in the 1900's. Bus systems replaced streetcars, and as commuters switched to personal cars, the for-profit bus companies got out of the business in the 1930's-1950's. Some private bus companies simply disappeared, while others were acquired by local jurisdictions and operated as a public service.

Population growth after World War II and Federal funding for highways led to expansion of the suburbs and ever-greater traffic congestion in Hampton Roads, Richmond, and Northern Virginia. The search for solutions led to creation of Metrorail in the DC area, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) commuter railroad in Northern Virginia, plus The Tide light rail system in Hampton Roads.

in 1973, Shirley Highway had dedicated bus lanes

Source: National Archives, Shirley Highway In Virginia. Heavy Traffic And Clear Bus Lanes

The cost of rail-based transportation led to a search for alternatives, and the decision to use Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) in Alexandria, Arlington, and Richmond.

Virginia Beach also considered a BRT link from Town Center to the Oceanfront. The city dropped plans to extend The Tide light rail system from Norfolk to Town Center in 2016 after a public vote rejected the proposal, and without the light rail connection to Town Center the plans for a BRT extension to the resort area on the waterfront also died.

BRT systems are designed to mimic rail systems, with tickets purchased in advance before boarding the bus. Bus platforms are level with the bus itself, eliminating the steps required to board from traditional curbside bus stops. Most significantly, BRT routes use dedicated lanes to bypass traffic congestion.

BRT vehicles resemble passenger rail cars and create the impression of a premium transportation service suitable for middle-class passengers, in contrast to the reputation of local buses being the transportation system for the poor. The buses are powered by internal combustion engines; unlike light rail and old trolley systems, no unsightly overhead power lines are required.

The primary advantage of BRT systems over light rail is that construction costs are lower. The primary advantage of BRT systems over traditional bus systems is that BRT vehicles reach their destination faster than traditional buses trapped in traffic on regular highway lanes, thanks to the special lanes used only by BRT vehicles.

Richmond built a 7.6 mile Broad Street Bus Rapid Transit project, the Pulse. The transit route connects Rocketts Landing on the eastern edge of downtown to the West End shopping center at Willow Lawn. By using three miles of dedicated BRT lanes, built parallel to the existing Broad Street, passengers using the BRT line travel one-third faster at 13mph rather than 8mph. That speed would save 14 minutes per trip from end-to-end, assuming any residents in the new apartments/condominiums built on the eastern edge of downtown needed to travel to Willow Lawn.

Congestion relief on I-64 was cited as one justification for requesting $50 million in Federal/state funding to construct the new lanes and purchase the buses. Local sources would fund 25% of the initial construction costs, but 100% percentage of operating costs.1

The choice of BRT technology in Richmond reflected both physical constraints and basic objectives for the project. The trolley network built in the 1880's demonstrated clearly that Richmond's hilly topography was not a barrier to a rail transit system, but 130 years later there was no room available on the city's congested street network for a light rail line.

The other alternative was expansion of the Glenside Express Bus service, which would be the most cost-effective way to reduce commuter-generated congestion on I-64 between downtown Richmond and the West End suburbs. However, improving that transit service would provide no land use benefits.

A BRT system along the Board Street Corridor can service customers moving between 14 stations, rather than just commuters living in the West End. The infrastructure investment in building the BRT line was projected to create a perception that transit services would be provided permanently, triggering increased investment by private sector landowners near the route. The "BRT effect" was expected to catalyze development along Board Street, especially west of Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), as well as increase access to downtown redevelopment projects such as the proposed baseball stadium in Shockoe Valley.2

Richmond chose to use a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system rather than light rail to expand transit service between downtown and the wealthy West End suburbs

Source: Broad Street Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) study, Map of Study Area

Limiting the BRT system in Richmond to primarily the city, with just the Willow Lawn station in Henrico County and the Staples Mill station on the city/county border, minimized regional politics and eliminated any need to negotiate with Chesterfield County. Richmond, Chesterfield, and Henrico are part of the Richmond Metropolitan Authority (RMA), which focuses on toll roads and excludes bus service from its portfolio.

There are few regional transportation initiatives, and the bus system (GRTC Transit System) is managed separately. Efforts to revise membership on the Richmond Metropolitan Authority (RMA) board, to provide equal representation from each jurisdiction while compensating Richmond for previous investments in public parking garages and other infrastructure, failed in the 2013 General Assembly session. Membership was balanced and the organization renamed the Richmond Metropolitan Transportation Authority in the 2014 session.3

Arlington and Fairfax counties in Northern Virginia rejected the option of Bus Rapid Transit on Columbia Pike, but Alexandria adopted the BRT approach for the West End Transitway.

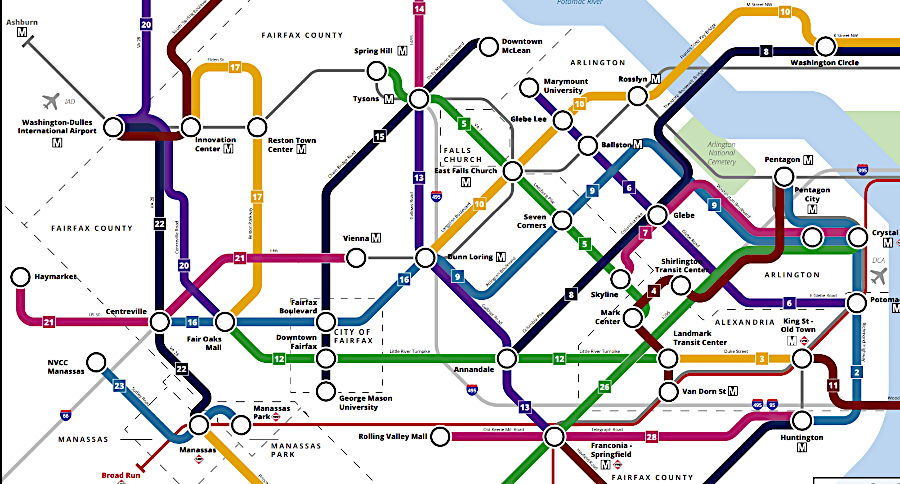

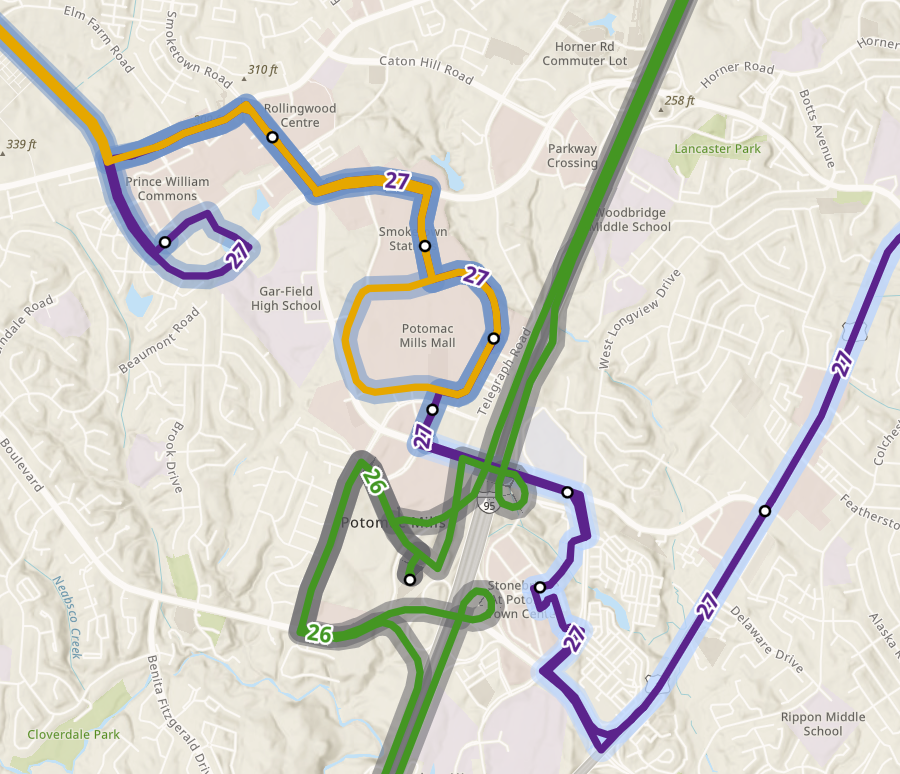

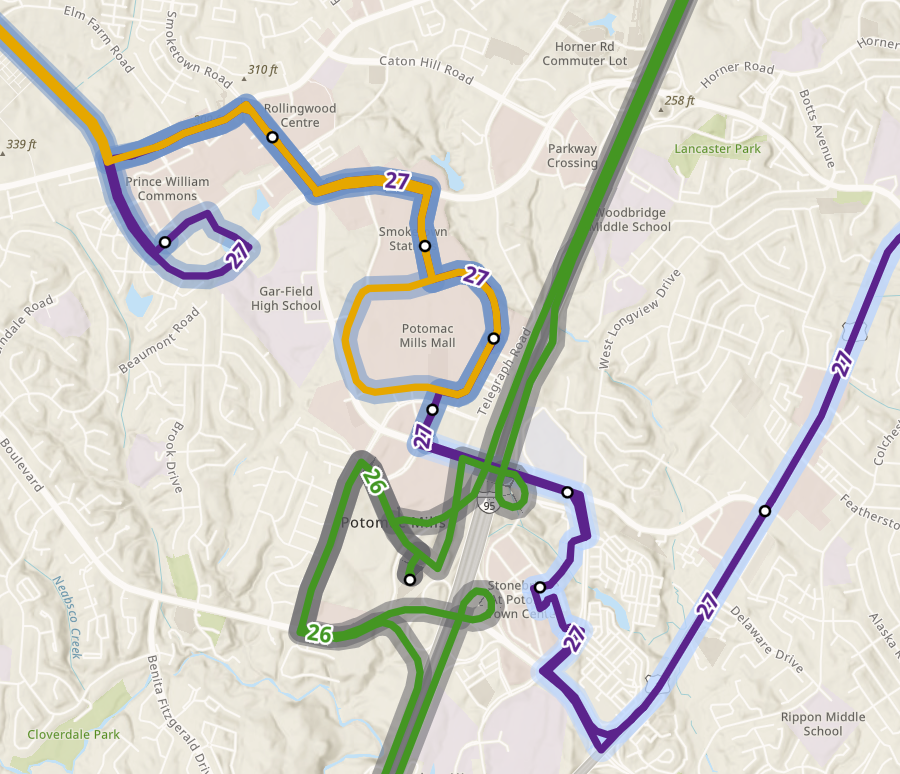

In 2025, the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority released a Bus Rapid Transit Action Plan. By that time, the regional transportation agency had already invested $880 million in building five routes, the Crystal City-Potomac Yard Transitway (Metroway), The One (Richmond Highway BRT), Duke Street Transitway, West End Transitway, and Route 7 BRT.4

bus rapid transit routes in Northern Virginia and around Potomac Mills in Prince William County, as proposed in 2025

Source: Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA), Shirley Highway In Virginia. Heavy Traffic And Clear Bus Lanes

Links

References

1. "Chesapeake looks to hop on light-rail bandwagon," The Virginian-Pilot, June 9, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/719024; City of Chesapeake, "2035 Land Use Plan," pp.101-102, http://www.cityofchesapeake.net/Assets/images/departments/planning/2035compplan/LandUsePlanADOPTED.pdf; Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation ,"Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan," June 2011, pp.ES-15-16, http://www.drpt.virginia.gov/activities/files/Final_Report_03-17-11.pdf (last checked June 10, 2014)

2. "State, Richmond seek $25M grant for bus rapid transit," Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 24, 2014, http://www.timesdispatch.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/state-richmond-seek-m-grant-for-bus-rapid-transit/article_a728bf50-cbba-11e3-902b-0017a43b2370.html; "Frequently Asked Questions," Broad Street Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Study, GRTC Transit System, June 15, 2012, http://study.ridegrtc.com/learn/BRT%20FAQ.pdf (last checked April 28, 2014)

3. "August 27, 2013 Public Meeting," Broad Street Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Study, GRTC Transit System, http://study.ridegrtc.com/documents/BRT%20Presentation%20Aug2013.pdf (last checked April 28, 2014)

4. "Draft Bus Rapid Transit Action Plan," Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA), April 2025, p.3, https://thenovaauthority.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/NVTA-Final-Draft-Action-Plan.pdf (last checked April 25, 2025)

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places