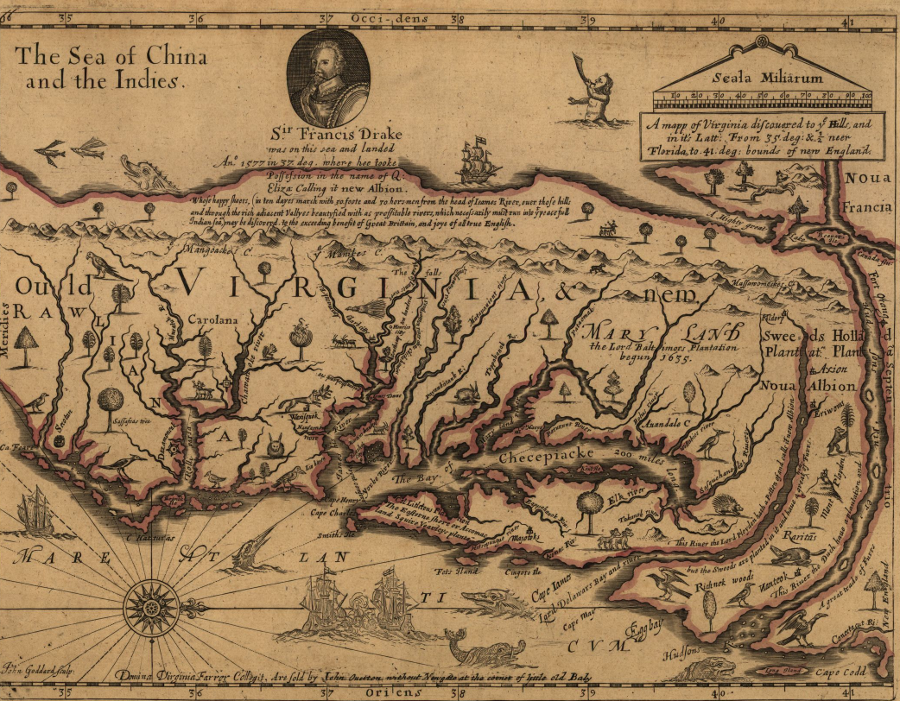

Early Settlement Up the... Rappahannock?

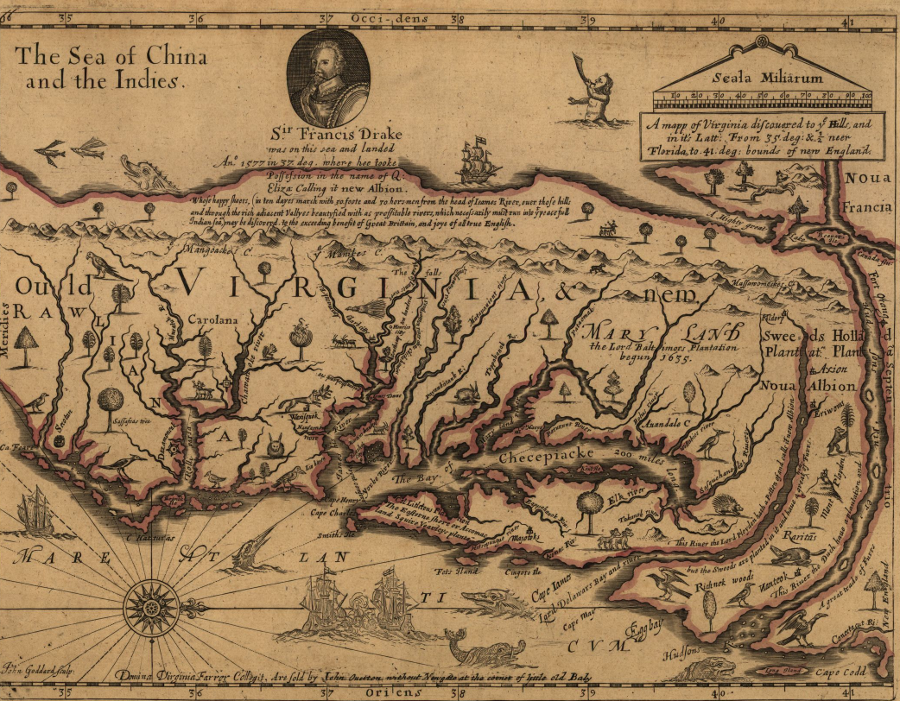

the map produced by John Farrer in 1651 placed the James and Rappahannock rivers at the center - settlement of the Roanoke and Potomac watersheds came later

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it's latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England (1657 revision by Virginia Farrer of 1651 map by her father John Farrer)

In 1607, the first English colonists arrived in Virginia. They could have settled at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, at modern-day Norfolk and Virginia Beach. However, their instructions were to find a spot far enough upstream to provide warning if Spanish, French, Dutch, or others chose to attack the new settlement.

Rather than turn north after entering the Chesapeake Bay, Christopher Newport continued to sail west and followed the large James River upstream. He explored all the way to the Fall Line, where Richmond is now located, before the colonists determined to settle on Jamestown Island. As a result of that decision, English settlement in the colony of Virginia grew outward from Jamestown, up the James River to the Fall Line and down the river to the Chesapeake Bay. Significant settlement on other Tidewater rivers occurred only after the colonial population growth exceeded the supply of unappropriated land along the James River.

The early colonists stuck close to Jamestown for convenience. As the population grew, new communities were developed at places along the James. The first General Assembly, held in 1619, included delegates from 10 "plantations" - and all were on the James River (James City, Charles City, City of Henricus, Kiccowtan, Brandon, Smythe's Hundred, Martin's Hundred, Argall's Gift, Flowerdieu Hundred, Captain Lawne's plantation, and Captaine Warde's plantation).1

The English did not stick to the James River valley out of ignorance. They knew other suitable lands were available on additional rivers. In 1608, John Smith mapped the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries in two separate voyages. His men sailed and rowed upstream to the Fall Line on the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, discovering boat-stopping rapids comparable to what Smith had seen on the James River when he first arrived a year earlier.

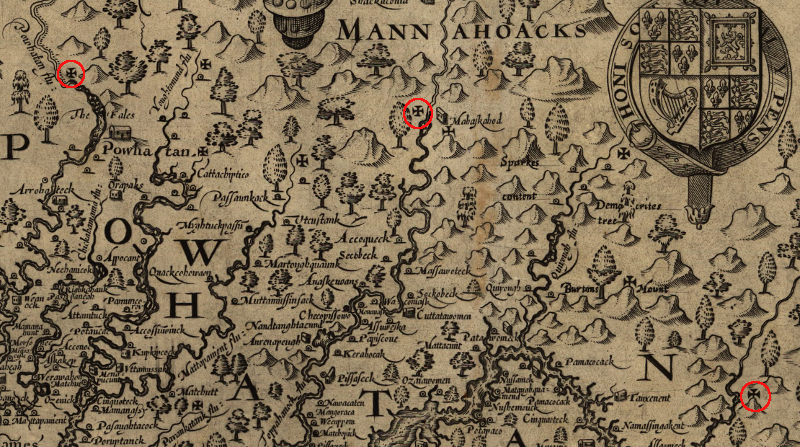

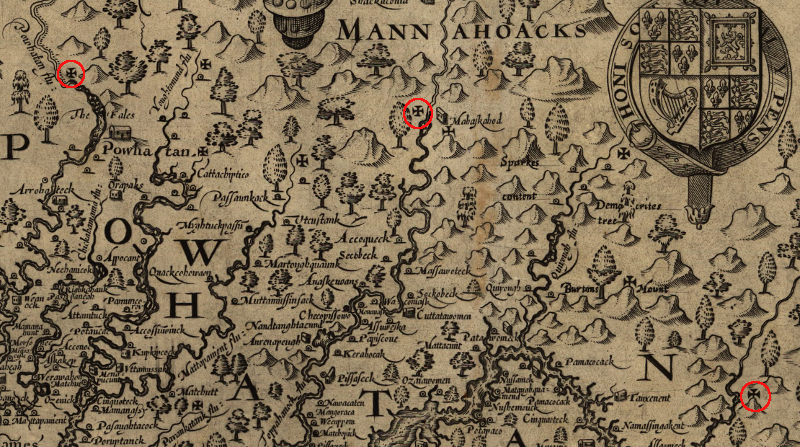

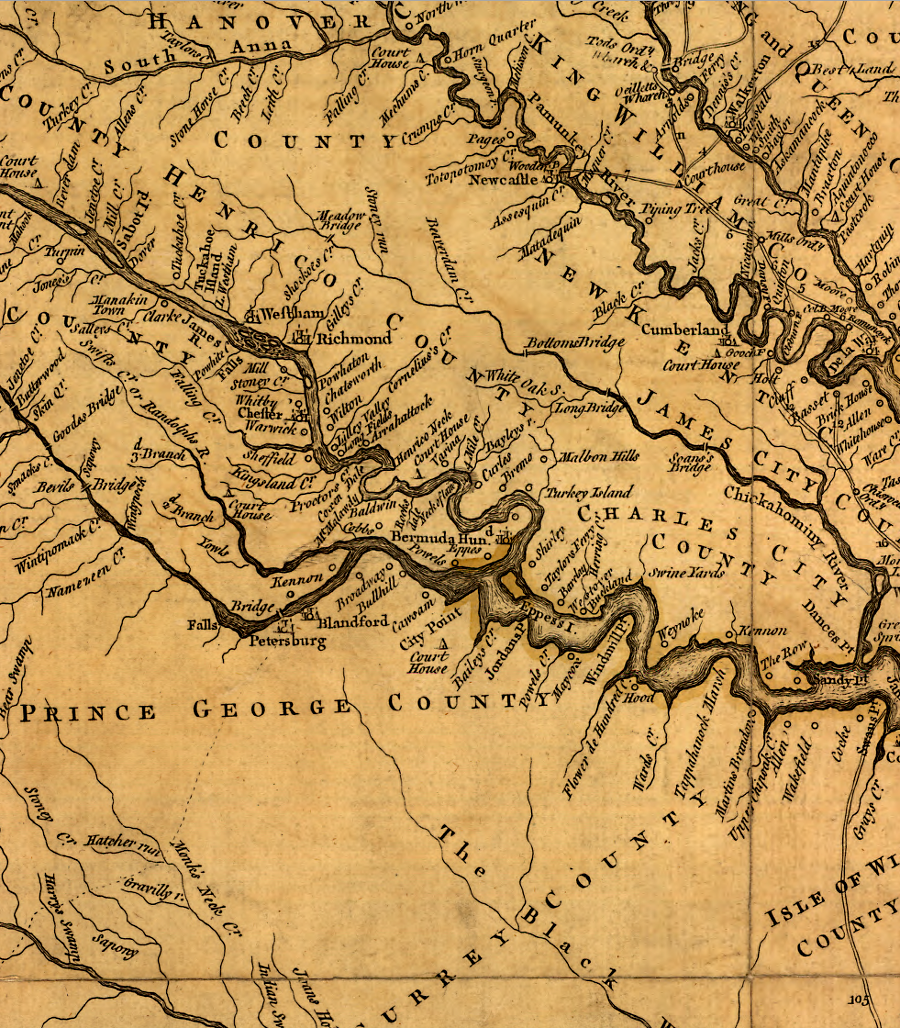

Rappahannock River, explored by John Smith in 1608 ("Powhatan flu" is the James River)

Source Map: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

Smith's first encounter with the Rappahannock River was on his first journey - and it was a painful one, when a jab from a stingray tail made him think he was going to die. (Ever since, the location at the mouth of the Rappahannock River where he was stung has been known as Stingray Point.) On Smith's second exploration of the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, he returned to the Rappahannock and maneuvered upstream.

A pair of Maltese crosses on his map of Virginia marks where Smith and his fellow explorers reached the Fall Line at modern-day Fredericksburg. At the head of navigation on the Rappahannock River, Smith was constrained to just looking to the west, beyond the Fall Line. He was unable to get his shallop past the rapids and explore further upstream to find a path to the Pacific Ocean.

According to one account, on August 22, 1608 Smith stood on the riverbank at Belmont and again on top of Fall Hill, just as he had found vista points on the falls of the James and Potomac rivers earlier.2.

Falls on the James, Rappahannock, and Potomac rivers, marked by Maltese crosses

Source Map: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

Smith had to rely upon the accounts of the Native Americans that he met regarding the geography of Virginia west of the Fall Line. In addition to the communications challenge of translating between the Algonquian and English languages, Smith also had to wonder how complete and honest were the reports he received about the lands upstream. On his way up the Rappahannock, he was welcomed by the Moraughtacund tribe at Lancaster Creek, attacked by the Rappahannock tribe near modern-day Tappahannock. While at the falls on August 22, his party was attacked by Siouan-speaking Mannahoacs who lived west of the Fall Line, but Smith ultimately made peace and quizzed the Mannahoacs regarding the reports of mountains to the west of their town. Similarly, he made peace with the Rappahannock tribe and created the opportunity for future trade, bypassing Powhatan's control.

The second fort developed by the Virginia Company, after Jamestown, was Henricus. It was located 30 miles further up the James River - further away from the Spanish, at a location thought to be easier to defend against European attack. Obviously the expectation was that Virginia would be centered on the James River.

Henricus was destroyed in 1622, and it took decades before enough English had arrived to occupy the good lands along the James upriver from the Chesapeake Bay and downriver from the falls. When enough settlement developed to justify creating counties so residents could handle basic legal matters without traveling to Jamestown, the central significance of the James River was obvious in the location of the county boundaries.

In the second decade of the 18th Century, a century after Jamestown was settled, much of the property adjacent to Tidewater rivers had finally been claimed. When Governor Spotswood assumed office in 1710, it was clear that future plantations would develop west of the Fall Line. Shipping costs would be significantly higher west of the rapids, but roads could be built to bring tobacco, corn, wheat, deer hides, and other valuable trade products to the ships that connected Virginia to the international markets.

The obvious place for new settlement was on the James River, above the falls that had blocked ships ever since Christopher Newport sailed up the river in 1607. Since the destruction of the Henricus settlement in the Native American uprising of 1622, no population center had developed at the upstream end of the James River. Population growth had occurred in the middle of the peninsula between the James and York rivers. The colonial capital moved from Jamestown to Williamsburg - further away from the river, but not further upstream - in 1699.

Governor Spotswood tried to steer where the new development in the Piedmont would occur. Encouraging new settlement in the James River watershed above the Fall Line might have made sense to him. Ships sailing up the James River had access to more wharves than on any other river. Settlers upstream of the falls on the James River could build roads to connect inland plantations to the great number of ships already using the James River below the rapids.

Encouraging new settlemment in other watersheds made less sense:

- There were fewer plantations and less shipping on the lower Rappahannock. In comparison to the James, ships would need more time to sail upstream to the Fall Line on the Rappahannock.

- Governor Spotswood had no opportunity to offer free land to spur development in the Potomac River watershed. King Charles II had issued a proprietary grant for the Northern Neck in the 1660's, and Lord Fairfax claimed the right to sell all land between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. The north bank of the Potomac River was controlled by the separate colony of Maryland.)

- South of the James River were large areas not densely settled by the English in 1710, but close to the James River. Spotswood could have steered population growth to that area, but it lacked water access to the Chesapeake Bay. South of the watershed divide, all the shipping from new settlements would float downstream to Albemarle-Pamlico sound, which was under control of the North Carolina colony. Governor Spotswood had no intention of encouraging economic development in a rival colony.

Spotswood choose to push for new settlement in the Rappahannock River watershed, probably because he mixed opportunities for personal economic gain with his official responsibilities. A rival in Virginia, William Byrd II, had already acquired patents to the land around the falls of the James River. As described by one writer4

- "The Rappahannock did not lack shipping facilities, but its course, lying to the north of the James, was not so near to the center of population. It was this stream however which Spotswood undertook to develop as the first avenue to the West, and it is a reasonable assumption that he did so because Byrd had preempted the strategic commercial position at the falls of the James."

Spotswood acquired significant amounts of land near the Rappahannock River. He built his own iron production facility, the Tubal Works, in the county named after him - Spotsylvania. In 1714, he arranged for supposedly-abandoned immigrants from the German Palatinate and Swiss cantons to be settled on lands he controlled at Germanna. Spotswood disguised their primary activity, to develop his iron deposits, by describing the settlers as defenders of the frontier. When he decided to assess the threat of French invasion through the gaps in the Blue Ridge, he combined the 1716 military-oriented trip with a real estate tour and the route of the "Knights of the Golden Horseshoe" expedition took the travelers into the headwaters of the Rappahannock River.

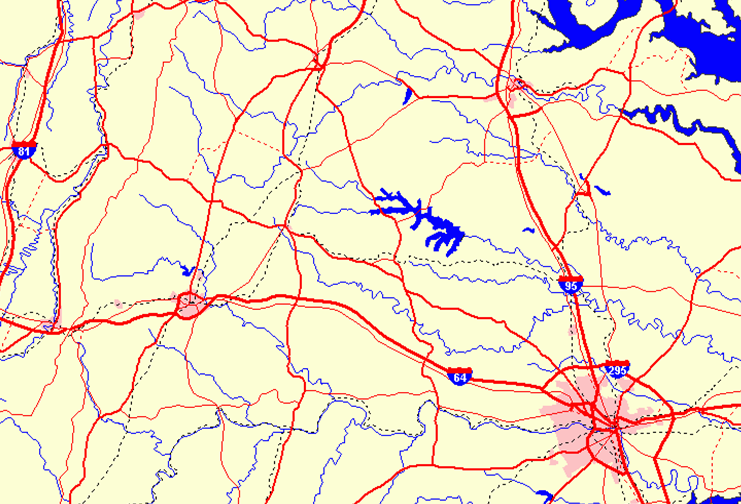

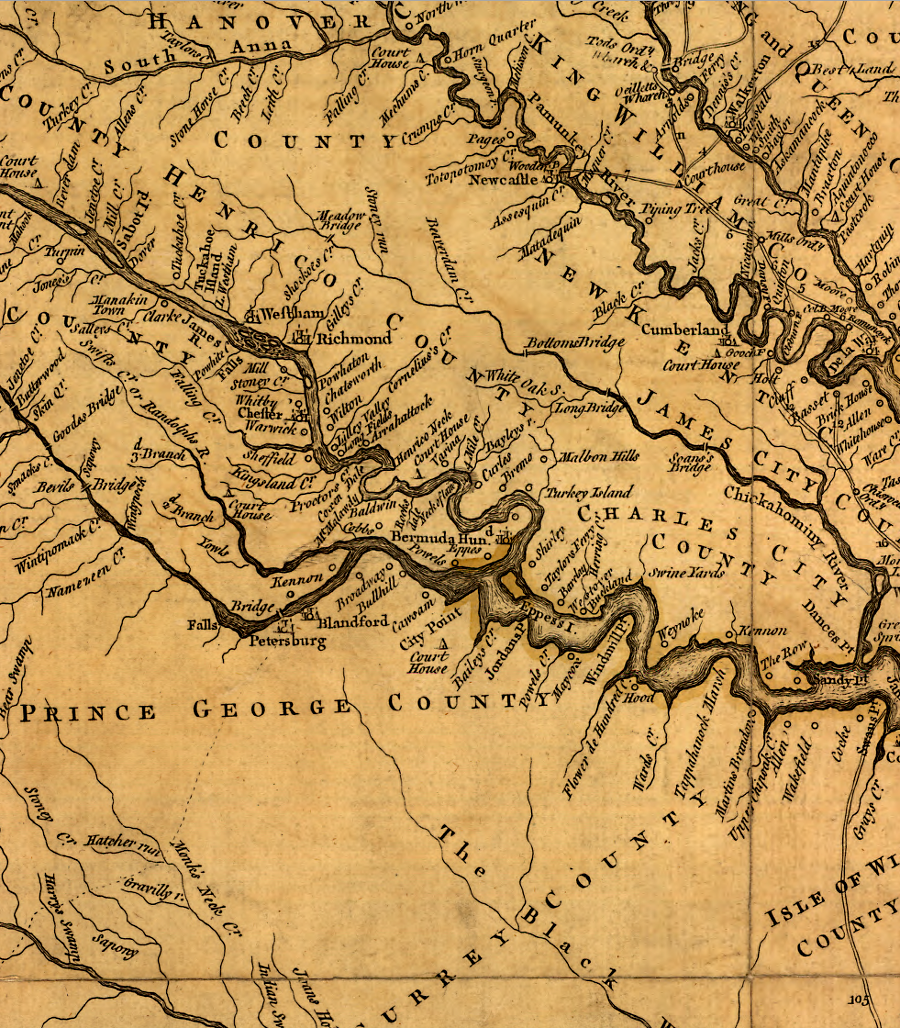

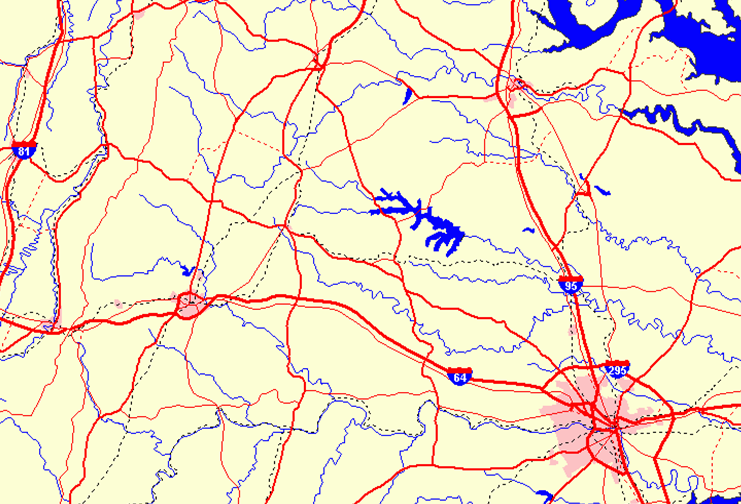

possible settlement paths up Rappahannock and James rivers

(as drawn by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson in 1751)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina

Spotswood was not successful in steering growth up the Rappahannock. William Byrd chartered cities at the falls of the Appomattox River and the James River, and they developed into Petersburg and Richmond. Turnpikes, canals, and railroads directed trade to those two port cities, and Fredericksburg never grew into a significant economic rival.

Both historic and modern transportation infrastructure show the relative economic development of the James River vs. the Rappahannock River watersheds. No canal was ever completed upstream of Fredericksburg. The narrow-gauge Potomac, Fredericksburg and Piedmont Railroad extended west from Fredericksburg to the Piedmont, but it was short-lived. No interstate highway provides east-west connections from the Blue Ridge to Fredericksburg, in contrast to I-64 for Richmond and I-66 for Alexandria.

modern transportation infrastructure - James vs. Rappahannock watersheds

(dotted black lines are railroads)

Source Map: USGS National Atlas

Links

References

1. "A Reporte of the manner of proceeding[K] in the General assembly convented at James citty in Virginia, July 30, 1619, consisting of the Governor, the Counsell of Estate[L] and two Burgesses elected out of eache Incorporation and Plantation, and being dissolved the 4th of August next ensuing," in Colonial Records of Virginia, originally published 1874, Project Gutenberg eBook online at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22594/22594-h/22594-h.htm (last checked September 3, 2010)

2. "Crosses Mapped by Smith," John Smith Trail website, http://www.smithtrail.net/captain-john-smith/smiths-maps/crosses/ (last checked September 3, 2010)

3. "Overview of Smith s Second Chesapeake Bay Voyage," John Smith Trail website, http://www.smithtrail.net/pdf/voyage_2.pdf (last checked September 3, 2010)

4. Abernethy, Thomas Perkins, Three Virginia Frontiers, Peter Smith, Louisiana State University Press, 1962, p. 32

the 1755 Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia shows the relative lack of development south of the James/Appomattox rivers, in the watersheds of the Blackwater and Nottoway rivers that did not flow to the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places