The High-Speed Rail Dilemma of Hampton Roads

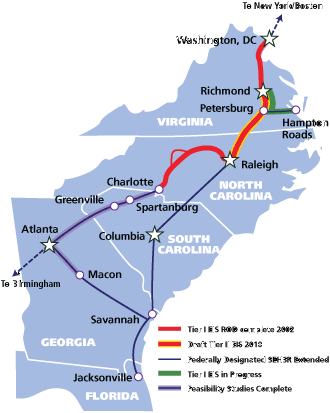

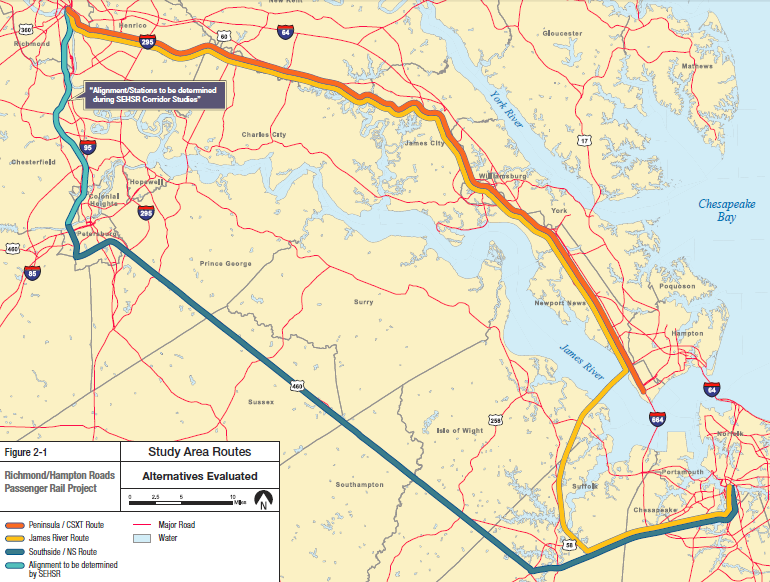

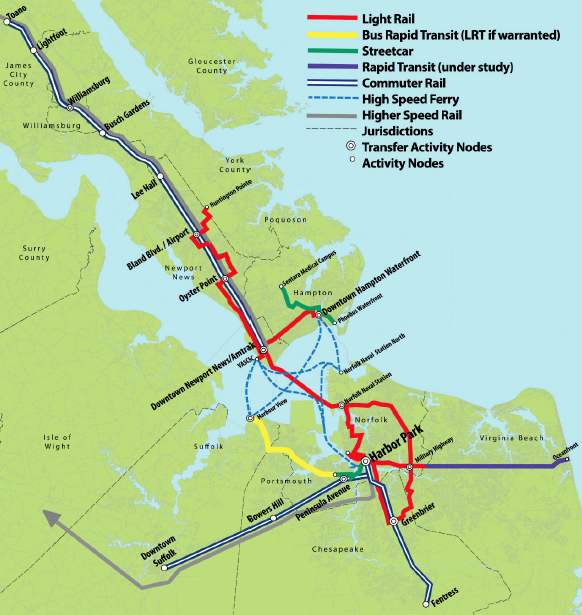

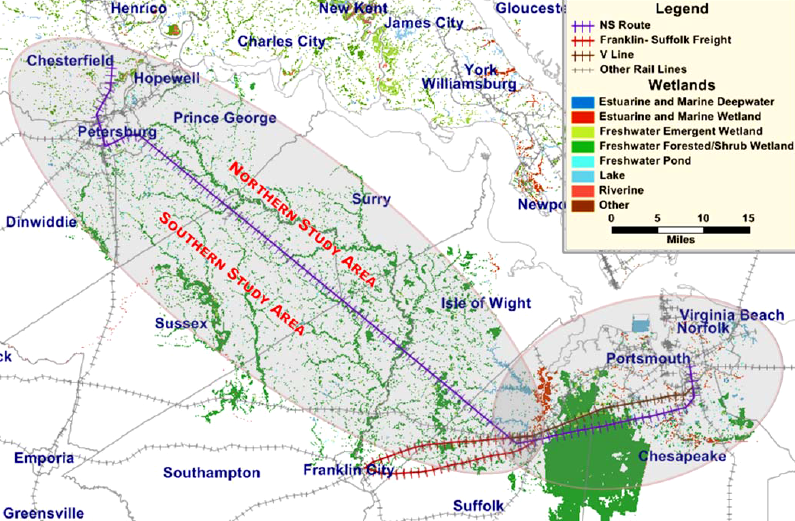

proposed high-speed rail routes to Hampton Roads

(CSX line located on Peninsula north of James River, Norfolk Southern line located south of river)

Source: base map from National Atlas, routes from Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project

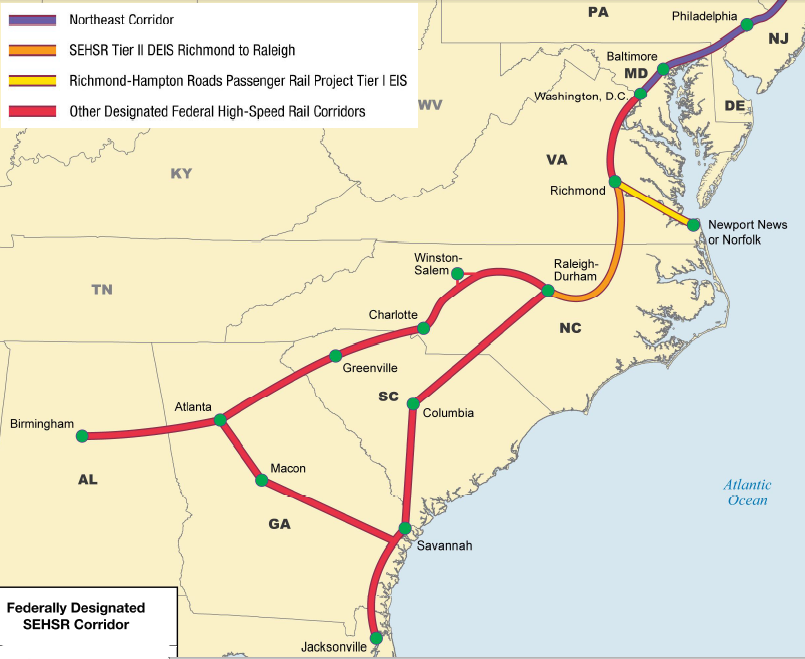

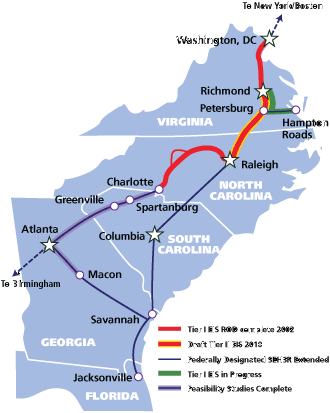

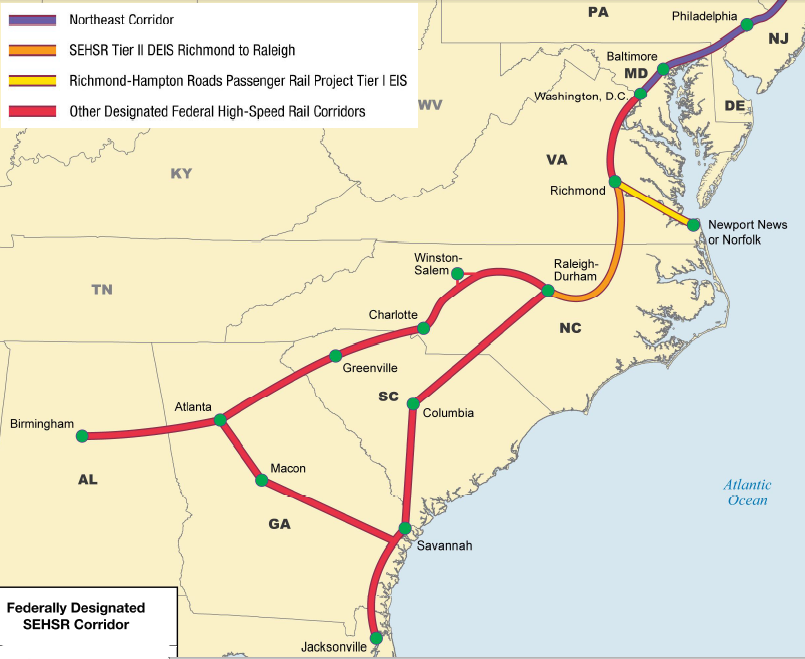

proposed Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor, showing Petersburg-Norfolk as a spur line and Richmond-Raleigh as main line

Source: Southeast High-Speed Rail Corridor

Passenger rail service returned to Norfolk in December 2012. Norfolk is now seeking to be added to the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor, hoping to upgrade existing service and initiate "high-speed" (110mph or greater) passenger rail service in southeastern Virginia.

For now, passenger service to Norfolk will be at conventional speed over existing Norfolk Southern freight rail tracks between Petersburg-Norfolk. Unless a separate passenger-trains-only track with advanced signals can be financed and constructed parallel to the current freight rail line, trains on the straight stretch of rail from Petersburg-Suffolk will be limited to 79mph. That speed limit was established after two trains crashed at Naperville, Illinois in 1946. Before the Interstate Commerce Commission imposed speed limits based on signaling capabilities of different stretches of track, some passenger trains in the Midwestern states traveled as fast as 110mph.1

Proposals to invest in rail improvements in the Hampton Roads region expose a traditional Peninsula vs. South-of-the-James-River split, when there are not enough resources to finance multiple projects that would satisfy all regional interests. Regional leaders struggle to adopt common regional priorities for transportation investments, since some of the most expensive proposals (such as the Patriot Tunnel) would benefit only certain sections of Hampton Roads.

These modern conflicts between North-of-the-James River Hampton Roads and South-of-the-James River Hampton Roads echo the sectional battles in Virginia prior to the Civil War. Back then, the political elite focused on funding canals to serve the Potomac River (Alexandria) vs. James River (Richmond) business interests. On the James River, there were upriver vs. downriver sectional conflicts; business leaders in Richmond/Petersburg tried to block extension of railroads to the competing ports at Portsmouth/Norfolk.

Norfolk has created a transportation hub at Harbor Park, allowing passengers to transfer between the local light-rail "Tide" system to Amtrak and (ultimately) high-speed rail, as well as local ferries and bus lines. The State of Virginia committed $114 million to upgrade the rail lines as required for bringing Amtrak service to Norfolk, and Norfolk spent $3 million to build a new 3,500-square-foot intercity passenger rail station at Harbor Park.2

"Tide" light-rail route, headed east from Harbor Park towards Norfolk State University and Harbor Park Tide station under construction, September 2010

Why spend so much money? Passenger rail makes Norfolk more accessible from Central and Northern Virginia, rather than a cul-de-sac location off the beaten path that is unattractive for modern businesses. Passenger train access to Richmond, Washington, and New York makes Norfolk more attractive to businesses, especially Department of Defense agencies and their contractors.

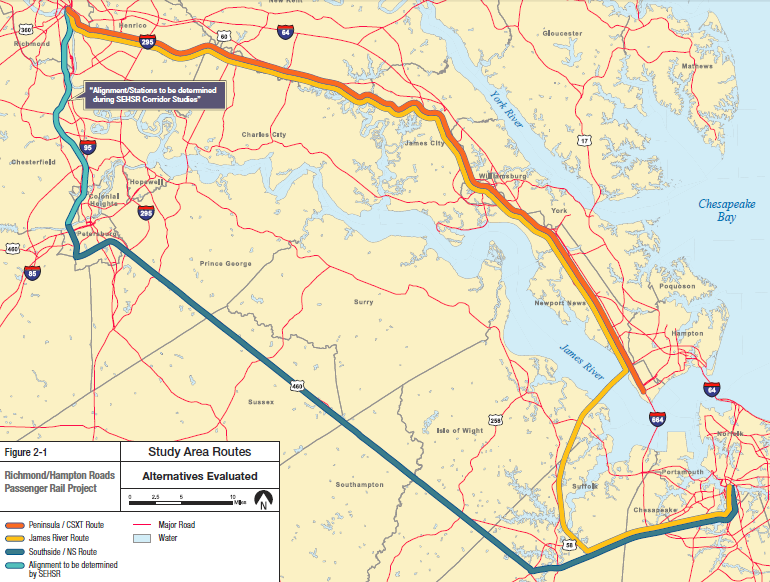

In the Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project, state and Federal officials examine the potential to provide higher-speed rail to both Newport News and Norfolk. With enough money, regional interests on both sides of the James River can both be satisfied. In 2010, the Commonwealth Transportation Board chose Alternative 1, to provide three conventional speed (79 mph) trains along the Peninsula/CSX route and six higher speed (90mph) trains to Norfolk.3

However, funding shortfalls still may force state/Federal officials into making a hard choice between improving rail infrastructure north vs. south of the James River.

alternatives to link Norfolk to Richmond/Washington included building a new railroad bridge over the James River

Source: Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project, RHR Public Hearing Exhbits - Maps

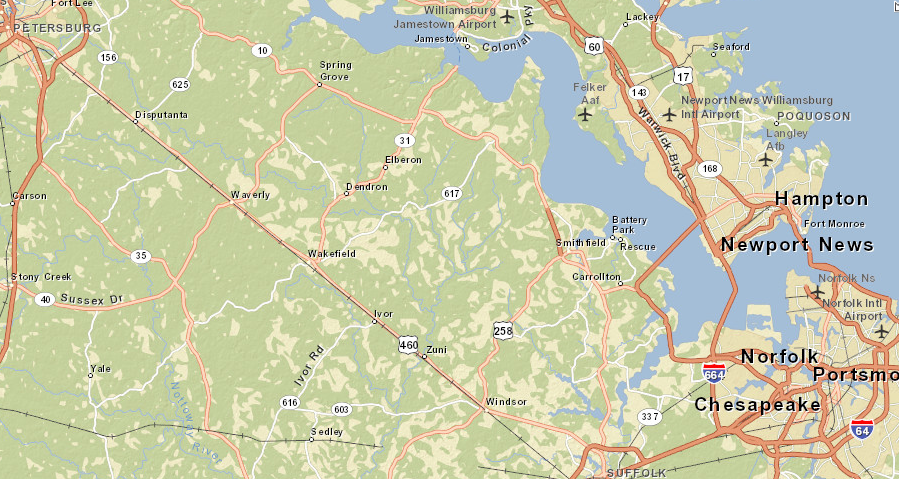

The basic problem: Hampton Roads, north and south of the James River, is the end of the line. Norfolk/Virginia Beach are at the edge of the urban megalopolis that stretches from Boston to Washington (the "Bo-Wash Corridor" or "Urban Crescent"). Development is extending south to Richmond and perhaps to Raleigh. Business leaders in southeastern Virginia fear their area will be bypassed, rather than integrated into the economic development of the Urban Crescent.

Civic leaders in South Hampton Roads (south of the James River) want the expanding pattern of development to veer southeast from the I-95 corridor, so the cities of Suffolk, Chesapeake, Portsmouth, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach can reap the economic benefits associated with growth. When passengers as well as freight travelled by ship, Norfolk and Virginia Beach were just as connects as Richmond to New York and Boston. Since the 1920's, roads have replaced ships, and Hampton Roads is isolated from the urbanized metropolitan area that extends from Boston down I-95.

There is one interstate highway that goes east from Hampton and Virginia Beach. I-64 loops around Norfolk and crosses the James River via the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel and (as I-664) via the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel. Nonetheless, it is a long drive through congestion on I-95 to reach Washington or points further north. Airline connections from Norfolk and Williamsburg-Newport News are also inconvenient.

High speed rail is the "silver bullet" solution, theoretically allowing business and civic leaders to get back and forth to DC in one day. The rail consultant hired by the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization claimed in 2014 that high speed trains could get from Norfolk to DC in just 98 minutes, and the demand would be sufficient to pay operating costs and cover some construction costs as well. (State officials described that analysis as "naive.")4

Virginia Beach, Norfolk, Chesapeake, and Suffolk will have to use the Norfolk Southern line that parallels US 460 from Norfolk to Petersburg; there is no realistic way to build a rail line across the James River to link South Hampton Roads to the CSX line than runs from Newport News to Richmond. South Hampton Roads can build new bridge-tunnels for cars and trucks, but getting a rail across the James River is far more difficult. Cars/trucks can drive up a 7% grade, but trains are severely limited by grades greater than 1%.5

night lights reveal the distance between developed areas in Hampton Roads and I-95 corridor

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Worldview, Earth at Night 2012

Because the developed area of Hampton Roads south of the James River is isolated by swamps to the south, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the marginally-populated Eastern Shore to the north, the cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, and Suffolk are not in the vibrant middle of any road network. Virginia Beach is a destination resort, because it is at the end of the road rather than on the main route (I-95). People plan in advance to attend business conferences or enjoy a vacation at Virginia Beach; travelers from north/south and east/west do not go there casually.

One sign of the isolation: Hampton Roads is the largest metropolitan community in the United States without a professional major league sports team and also lacking a major college athletics team. Old Dominion University is trying to fill part of the gap. The university launched a football team in 2009 and sold out games regularly, so in 2013 it proposed to build a new 30,000-seat stadium with potential for expansion to 45,000 seats.6

Hampton Roads has always struggled to grow. The area was bypassed at the beginning of colonial development because the 1607 settlers moved upstream to Jamestown, to minimize the threat of Spanish/Dutch raiders. By 1775, the high-quality natural harbor had stimulated some town development. At the start of 1776, however, British sailors under Lord Dunmore and rebellious Virginians both participated in the almost-total destruction of Norfolk.

The city was rebuilt after the American Revolution, and by 1800 had more people than Richmond. However, the capital of Virginia boomed in comparison to Norfolk throughout the 1800's, as the state funded canals and railroads to bring business to the capital but largely ignored southeastern Virginia.

Norfolk's population did not climb faster than Richmond's until after railroads finally connected Norfolk to the interior, and then large propeller-driven steamships required deeper channels than sail-based oceangoing vessels. Getting rail to Norfolk involved complicated political and economic maneuvers. Modern concerns in Hampton Roads that the region will not receive its fair share for state-sponsored transportation improvements has a long history.

Richmond's population exceeded Norfolk's throughout the 1800's and most of the 1900's

Source: Bureau of Census, Rank by Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places, Listed Alphabetically by State: 1790-1990

Throughout the 1800's, Richmond and Petersburg (as well as Baltimore) viewed Norfolk as an economic rival. Shipping companies wanted to maximize the number of loads that ships could carry between coastal ports and across the Atlantic Ocean. Sailing up the James River to the Fall Line created a costly delay, compared to sailing directly from Norfolk. Richmond/Petersburg feared that ship owners would shift business to Norfolk, if cargo could reach that port directly via railroads. In the 1800's, Richmond and Petersburg conspired to block any railroad link between Norfolk and the hinterland west of the Fall Line, recognizing that a railroad connection would allow Norfolk to grow at the expense of the Fall Line ports.7

Port cities in Virginia have long competed for shipping traffic. Physical geography made Norfolk a more-attractive port location, in part because its harbor was naturally so deep. Prior to the Civil War, Richmond built a new port at the head of the York River at West Point, to provide a deeper harbor that was closer to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay - but Norfolk would always be closer to the Atlantic Ocean.

1856 map showing York River Rail Road connecting Richmond with West Point

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Springfield & Deep Run estates on the Coal Lands of the N. York & Richmond Coal Co,

in Henrico Co. Virginia, their relative position to the city of Richmond with rail road connections &c.

In the 1800's, Richmond/Petersburg and Portsmouth/Norfolk sought to dominate and control trade from the Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia. Rather than cooperate and build a network of lines that would benefit everyone, Richmond/Petersburg and Portsmouth/Norfolk tried to exclude the other from connecting to boats that travelled down the Roanoke River.

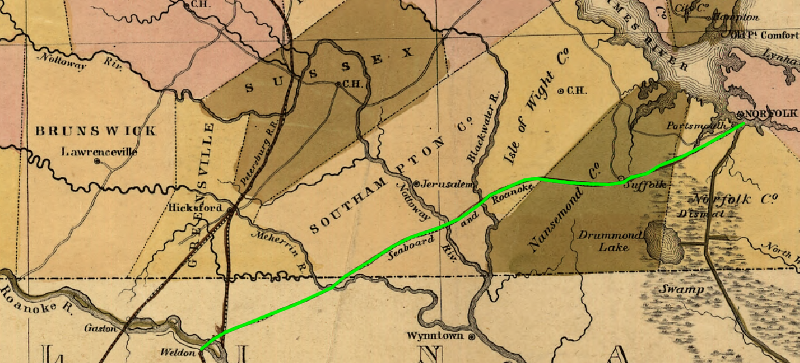

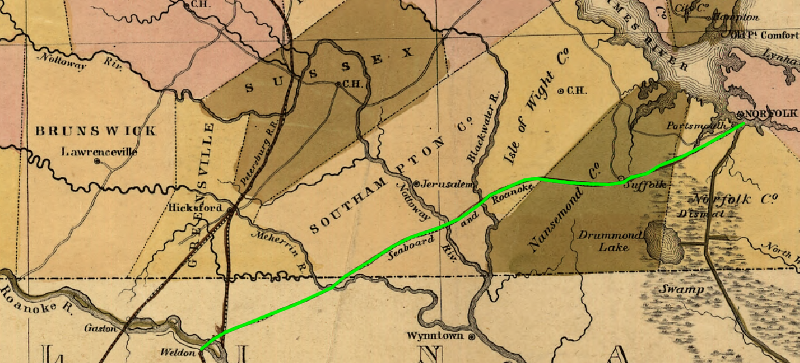

Seaboard and Roanoke (the Norfolk-to-Roanoke River railroad)

Source: Library of Congress,

Portsmouth managed to construct the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad to Weldon, the southern end of the Roanoke River Canal. That allowed the Hampton Roads port to tap into the trade from the Roanoke River watershed more effectively than the Dismal Swamp Canal had facilitated. Rival Richmond/Petersburg financial interests bought the debt of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad. With a claim of ownership, the new owners from Richmond/Petersburg then physically tore up the portion of the Norfolk line near the Roanoke River, forcing rail traffic to use the railroad to Petersburg.

railroads connecting to Richmond/Petersburg and competing with Norfolk, 1852

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant

Further inland, North Carolina demonstrated the same approach. It blocked development of a direct rail connection from its upper Piedmont to Virginia's ports, even though the North Carolina farmers would benefit from lower-cost transportation. Instead of allowing construction of a new rail line between Greensboro-Danville, North Carolina financed a state railroad to connect the western part of the state to Atlantic Coast ports in North Carolina. This was an early "smart growth" strategy, leveraging investments in transportation infrastructure to stimulate economic growth that - ideally - would create enough new tax revenues to repay the costs of the transportation project.

North Carolina officials feared the economic impacts of a rail connection to Danville, which was already connected to Richmond and Petersburg. Once a rail line was built, it was clear that North Carolina farmers would ship more crops and import more manufactured items through Chesapeake Bay ports. This would reduce business at the North Carolina ports of Wilmington and Morehead City, and the state investment in the rail connections to North Carolina ports would be wasted.

Piedmont Railroad - built during the Civil War to fill the gap between Greensboro and Danville

Source: Library of Congress Colton's new topographical map of the states of Virginia, Maryland and Delaware (1864)

To the dismay of North Carolina politicians, and over vehement objections of states rights advocates in the Confederate Congress, the Confederate Government built the Piedmont Railroad between Greensboro and Danville during the Civil War. The "national" government of the Confederacy under President Jefferson Davis mandated the new rail connection as a military necessity. The Confederate government saw the railroad connection as a war measure more important that states rights, since the Confederate Army needed food and material from the Deep South states. By 1862, after the Yankee blockade and capture of coastal ports such as Norfolk, the Confederate government needed interior lines of communication to supply the troops on the front line in Virginia.

After the Civil War ended, the Piedmont Railroad connection allowed North Carolina producers to avoid the circuitous route through Raleigh and the more-expensive ports on the North Carolina shoreline. Later, the development of the Seaboard Air Line and Atlantic Coast Line railroads, and the integration of other railroads into interstate networks, allowed farmers in Georgia and South Carolina direct access to Virginia and northern ports. That also facilitated inland trade that could completely bypass coastal ports like Norfolk, however. There was no need to ship cotton through a Virginia port to a New England textile mill, once the interior railroad network offered fast and cheap transport directly from the farmer to the manufacturer.

After the Civil War, Northern investors were able to purchase Virginia railroads and obtain new railroad charters. With the Seaboard Air Line, Portsmouth was able to connect via rail lines to the interior markets of the southeastern United States, even Atlanta. When railroads offered a network of connections, Hampton Roads ports would be the obvious low-cost provider of pot services. Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News traffic grew while Richmond/Petersburg ports stagnated. Richmond's railroad to deeper water on the James River at West Point ended up as a dead end, servicing just a paper manufacturing plant.

Norfolk benefitted from coal exports starting in the 1880's, after the Norfolk and Western (now Norfolk Southern) built a connection between the Appalachian coal fields and export terminals at Lamberts Point. Later, the Virginian Railway built more coal shipping capacity at Sewell's Point. Newport News developed when the Chesapeake and Ohio (now CSX) rail line was constructed down the Peninsula, creating a deepwater port that could compete with Norfolk and out-compete Richmond/Petersburg.

Alexandria, Petersburg, and Richmond declined as port cities between 1865 and 1900, while Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News (with 45' deep channels) benefitted from new rail connections to the docks at their ports. The C&O Railroad built its coal export facility at Newport News, while the Norfolk and Western Railroad built its coal export docks at Lamberts Point in Norfolk in the 1880's.

Today, Virginia politicians are quite aware of the potential economic impacts associated with construction of new railroad capacity. To overcome its isolation, Norfolk is fighting to be connected to a high-speed rail network being planned by the Federal and state governments. Whether high-speed rail is designed for passengers to relieve pressure on the airports, or even for freight to reduce the truck traffic congesting the Interstates, Norfolk want to be sure it's not bypassed by an inland rail route again.

The James River greatly complicates the plans of Norfolk, however. A quick glimpse at the map shows a rail line down the Peninsula already connects Hampton and Newport News to Richmond and points north. That's rail line was built by the C&O, which has been absorbed by the CSX Railroad. The interstate highways were routed the same way, and tunnels/bridges connected I-64 on the Peninsula to Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and other communities of south Hampton Roads.

Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O, now CSX) route down the Peninsula to Newport News

Source: Library of Congress Map showing the Norfolk, Wilmington & Charleston Railroad (1891)

However, there's no easy way to get a railroad across the water barrier of the James River. Unlike automobiles, high-speed trains can't climb overpasses or dip into steeply-slanting tunnels. Railroad locomotives require flat grades; there is no railroad bridge crossing the James River downstream of Richmond today. Amtrak stops at Newport News. Theoretically, engineers could design a railroad bridge crossing the James River between the Peninsula and South Hampton Roads, with a grade no greater than 1%, so Amtrak could provide service to Norfolk. However, a railroad drawbridge with a clearance of 60' above the water (comparable to the Route 17/James River Bridge) would require over a mile of track with a steady 1% grade on either side of the river. The land acquisition costs for such a project would be considerable...

Building a new railroad bridge or tunnel at a reasonable cost to carry high-speed trains from the Peninsula across the James River to "Southern Hampton Roads" would require a dramatic engineering breakthrough. One alternative: massive investment in purchase of new right-of-way and construction. Another alternative: carry rail cars across the James River on a ferry. There is no railroad bridge-tunnel connecting Virginia Beach/Norfolk with the Eastern Shore, comparable to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel - but the Bay Coast Railroad still transports rail cars between Little Creek and Cape Charles.

Realistically, ferries are slow and inefficient, and there would be would be unacceptable political impacts from condemning private property to build a new railroad bridge across the river. Extension of a rail line from the Peninsula to Norfolk, linking the two halves of Hampton Roads by a new railroad crossing of the James River, will not happen.

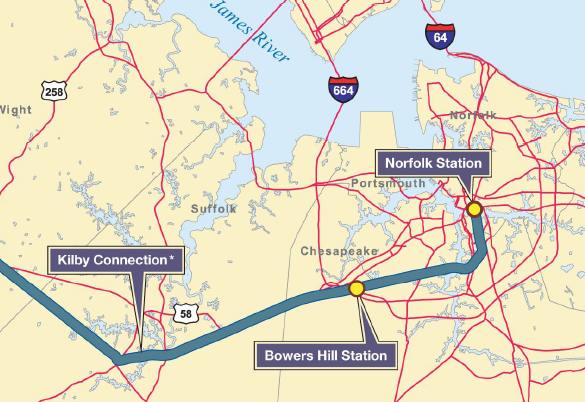

Norfolk has chosen a different option for obtaining high-speed rail: upgrade the existing Norfolk Southern line paralleling US 460 to Petersburg, perhaps even building a parallel line for high speed passenger trains. Compared to building a rail bridge/tunnel over the James River, construction costs for upgrading the existing rail line are smaller.

high speed rail options for Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project

The Federal/state/local governments could build high speed rail to Newport News as well as Norfolk - if money were no object. Because money is limited, the Commonwealth Transportation Board has chosen one high-speed rail route that benefits a portion of the southeastern Virginia more substantially than the rest. Norfolk, not Newport News, is supposed become the high-speed rail destination in southeastern Virginia. Trains could go 110mph between Richmond-Petersburg if the Southeast High Speed Rail corridor is implemented, then 90mph to Norfolk.

- For both the Newport News and Norfolk routes, all Richmond stops will be at Main Street Station (currently used only by Newport News trains). Passenger rail service is expected to spur economic revitalization in downtown Richmond; benefits from urban revival justify spending tax dollars to subsidize passenger rail at 79mph and faster. In the future, Richmond's Amtrak stop at suburban Staples Mill Station will be moved to the urban center.8

- In Newport News, however, the planners have a different vision. The current train station on Warwick Avenue would move nine miles away from the urbanized tip of the Peninsula. A new multimodal transportation hub is planned for the edge of the Newport News-Williamsburg airport on Bland Boulevard.9

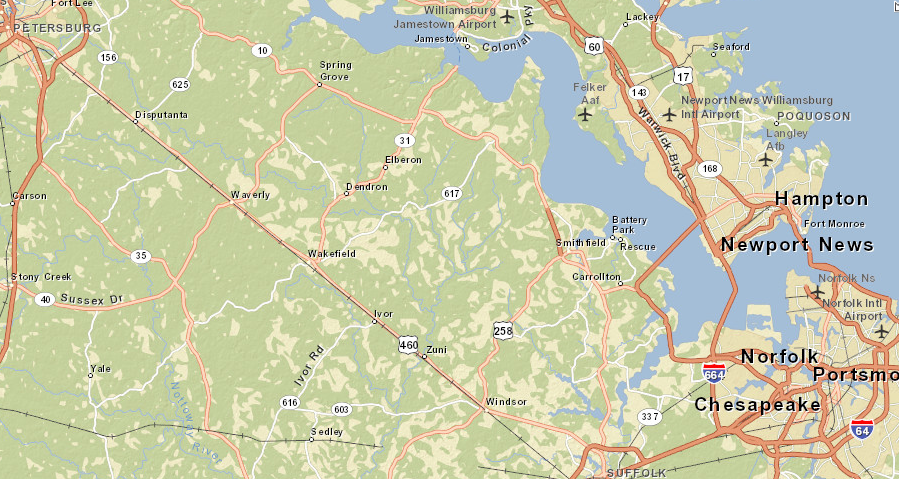

High-speed rail will service very few customers between Petersburg-Norfolk because the population there is so low. Since the intent of high-speed rail is to connect just a few locations without intermediate stops, skipping over the small communities is logical - but downtown Suffolk is also being skipped over.

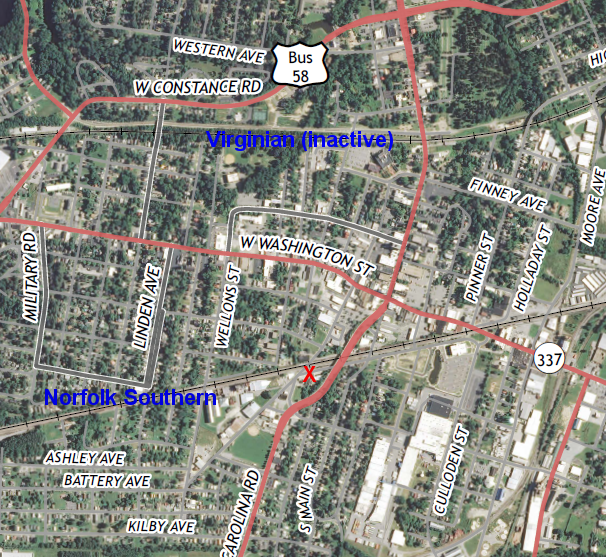

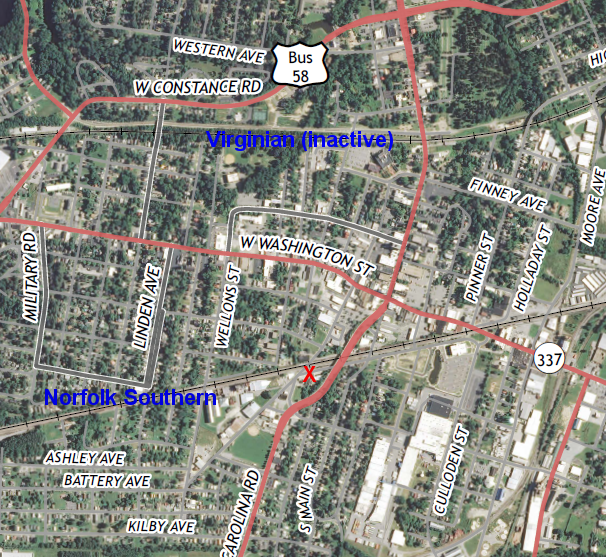

Suffolk has considered building a depot for Amtrak passenger trains, but the proposed location (red X) would not service future high-speed trains using the old Virginian tracks

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Suffolk 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013, Revision 1)

Until a final decision is made on routing passenger trains in southeastern Virginia, it is unlikely that Suffolk can obtain sufficient funding to purchase property and build a new train depot - even assuming the city could get Amtrak to add an additional stop. Trains will continue to roll through Suffolk at 60mph (freights were passing through at 40mph until 2013) without stopping.10

only small communities are located along the rail line between Petersburg-Suffolk

Source: ArcGis Online (Streets Basemap)

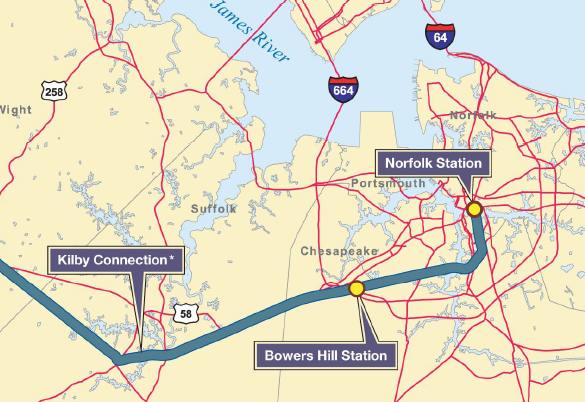

As currently proposed, there will be no high-speed passenger train stop at Suffolk, much less Windsor, Zuni, Ivor, Wakefield, Waverly, Disputanta. At Suffolk, trains would switch to the now-inactive Virginian Railway tracks near Kilby, then stop at Bowers Hill in Chesapeake before reaching the end of the line at Harbor Station in Norfolk. The Amtrak service to Norfolk, inaugurated in 2012, runs through Suffolk on the Norfolk Southern freight tracks, south of the old Virginian line. Suffolk has looked into the potential of building a passenger depot near the Peanut Park ballfield, but that would be over a mile away from high-speed trains if they use the Virginian route.11

high-speed trains are planned to stop in Chesapeake and Norfolk, but not in Suffolk or Portsmouth

Source: Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project, Tier I Draft Environmental Impact Statement (Page ES-3)

The maximum allowed speed of 90mph directly between Petersburg-Norfolk would provide faster end-to-end service. In contrast, on the Peninsula "high speed" would offer little time savings compared to standard 79mph service between Newport News-Richmond, because of the delay to stop at the intermediate station in Williamsburg (just 20 miles from Newport News).

Norfolk still needs support from the Peninsula, to get funding in the future to implement high-speed rail. The most visionary scenario, building a new "greenfield" rail line southwest of US 460 (perhaps using some of the abandoned right-of-way of the old Virginian railroad) would avoid conflicts with Norfolk Southern freight trains and allow the fastest possible speeds - but of course would require substantially more funding. If the entire region can't lobby steadily for implementing 90mph trains on the existing Petersburg-Norfolk rail line, then Federal funding for high-speed rail will go to other places in the United States.

In return, the Peninsula needs support from the Hampton Roads cities south of the James River for regional transportation projects, especially widening of I-64 to 8 lanes between Newport News-Richmond. In 2013 the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization unanimously endorsed building the Third Crossing as a higher priority than expanding the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, though in 2011 the mayor of Newport News said "There is no way this can be sold on the Peninsula side." After the unanimous vote in 2013, the Williamsburg mayor said "I never thought I'd live to see this."12

The Third Crossing projects, including the Patriot Crossing bridge-tunnel connecting the Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel to Craney Island/I-564 in Norfolk, could cost $5-6 billion. That is equivalent to the cost of the Silver Line extension in Northern Virginia. One stimulus for the unanimous decision to support the Third Crossing was Hampton Roads' regional competition with Northern Virginia for transportation funding.

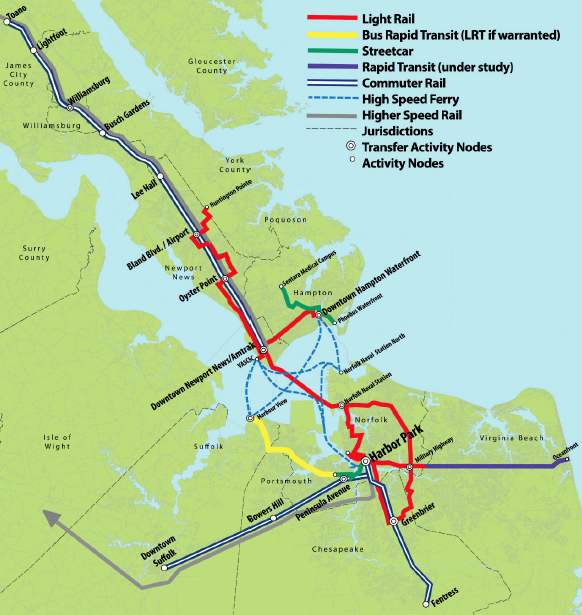

The Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan proposes the bridge-tunnel include a light rail line. The vision proposes a series of high-speed passenger ferries on the water to move people, but more-substantial economic revitalization opportunities would come from a transit network linking the cities of Suffolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Hampton, and Newport News.13

Hampton Roads vision for transit systems to link urban areas, including a light rail line crossing the mouth of the James River

Source: Hampton Roads Regional Vision Plan Map

Why isn't Virginia Beach considered a high-speed rail destination?

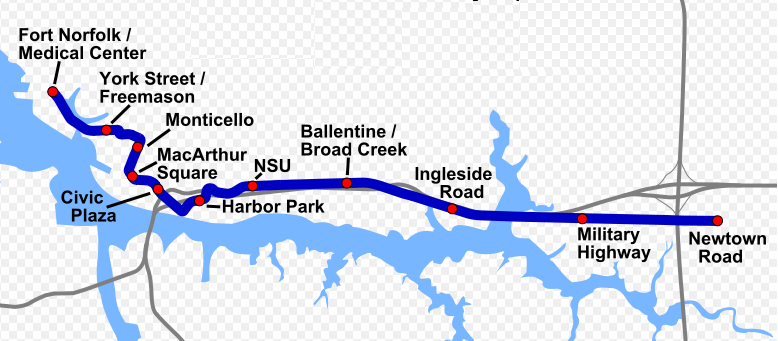

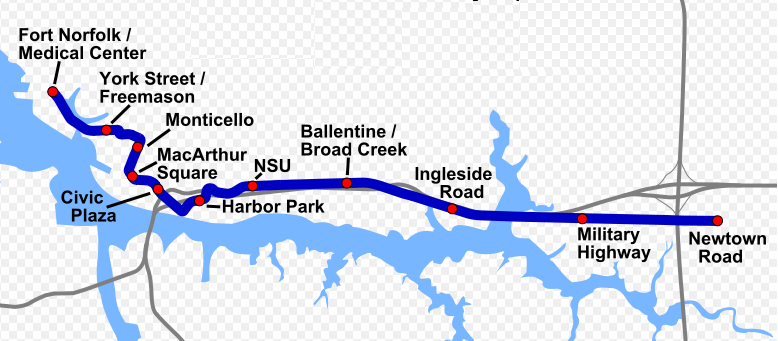

Virginia Beach no longer has a rail line connecting Norfolk to the resort area on the Atlantic Coast shoreline. There was such a rail line, built by the first Virginia railroad to be called "Norfolk Southern," but it has been abandoned. The city of Virginia Beach has purchased the abandoned right-of-way, and may use it for an extension of the Norfolk light rail system known as the Tide. The only option for passengers to ride a train east of the Harbor Park station in Norfolk is the Tide light rail system, going past Norfolk State University to the Newtown Road station at the border of Norfolk/Virginia Beach.

Tide light rail stations in Norfolk

Source: Wikipedia, Tide Light Rail

study corridor for extending light rail from Norfolk into Virginia Beach

(using route of a now-abandoned Norfolk Southern rail line)

Source: Hampton Roads Transit, Virginia Beach Transit Extension Study

potential routes for Tide extension to Oceanfront in Virginia Beach

Source: "Moving Forward," Virginia Beach Transit Extension Study (Vol.2, February 2013)

Links

Virginia seeks to extend the Southeast High Speed Rail (SEHSR) corridor to Hampton Roads

Source: Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project, Tier I Final Environmental Impact Statement (Figure 1-3)

References

1. "The Feds Put the Brakes on High-Speed Trains," Streamliner Memories, October 21, 2012, http://streamlinermemories.info/?p=358 (last checked August 31, 2013)

2. "Norfolk starts preparations for Amtrak train service," The Virginian-Pilot, October 8, 2011, http://hamptonroads.com/node/617230; "Amtrak ticket sales performing as expected," The Virginian-Pilot, July 23, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/node/684076 (last checked September 3, 2013)

3. "Commonwealth Transportation Board Selects Alternative 1 for Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, February 17, 2010 news release, http://www.rich2hrrail.info/downloads/CTBdecision.pdf (last checked August 13, 2013)

4. "Va. official: High-speed rail study may be too optimistic," The Virginian-Pilot, March 29, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/711630 (last checked April 18, 2014)

5. "Mountain railroading terminology," Trains, http://trn.trains.com/en/Railroad%20Reference/ABCs%20of%20Railroading/2006/05/Mountain%20railroading%20terminology.aspx (last checked September 3, 2013)

6. "Still a Minor Player," The Virginian-Pilot, February 4, 2003, http://www.sevenvenues.com/News/view/54; "Ten largest cities without a major pro sports franchise in North America," Yahoo Sports group, June 10, 2011, http://sports.yahoo.com/top/news?slug=ycn-8611569 (last checked August 13, 2013)

7. Peter C. Stewart, "Railroads and Urban Rivalries in Antebellum Eastern Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 81, No. 1 (January 1973), http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247766; "ODU envisions new, 30,000-seat football stadium," The Virginian-Pilot, August 20, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/node/687082 (last checked August 20, 2013)

8. "Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project Chapter 1 - Chapter 1, Purpose and Need," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, December 2009, Page 1-2, http://www.rich2hrrail.info/downloads/TierIFinalEIS/Tier%20I%20FEIS%20Chapter%201-2.pdf (last checked September 4, 2013)

9. "Taking the train from Newport News," The Daily Press (Newport News), February 7, 2013, http://articles.dailypress.com/2013-02-07/news/dp-nws-trains-20130207_1_train-service-multimodal-station-freight-trains; "Newport News Multimodal Passenger Rail Station Development," Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization, http://www.hrtpo.org/news/index/view/id/37 (last checked September 4, 2013)

10. "Passenger trains to start running soon," Suffolk News-Herald, October 5, 2012, http://www.suffolknewsherald.com/2012/10/05/passenger-trains-to-start-running-soon/ (last checked September 4, 2013)

11. "Richmond/Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Project - Executive Summary," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, December 2009, p.ES-6, http://www.rich2hrrail.info/downloads/TierIFinalEIS/Tier%20I%20FEIS%20Executive%20Summary.pdf; "Plans are on track, but will train stop in Suffolk?," The Virginian-Pilot, January 6, 2011, http://hamptonroads.com/2011/01/plans-are-track-will-train-stop-suffolk (last checked September 4, 2013)

12. "Hampton Roads leaders endorse third crossing," The Virginian-Pilot, June 20, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/2013/06/hampton-roads-leaders-endorse-third-crossing; "Peninsula leaders wary of third crossing priority," The Daily Press (Newport News), February 17, 2011, http://articles.dailypress.com/2011-02-17/news/dp-nws-hrtpo-retreat-20110217_1_hrbt-transportation-projects-simulation-center (last checked September 4, 2013)

13. "Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan - Final Report," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, February 2011, http://www.drpt.virginia.gov/activities/hrrtvp.aspx (last checked September 4, 2013)

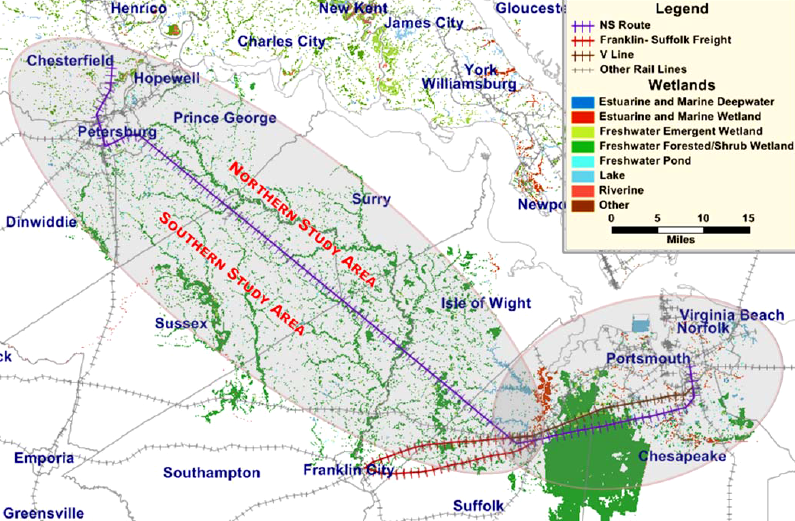

a new greenfield rail line, southwest of the existing Norfolk Southern freight line, could offer faster speeds - but conflicts with wetlands and cultural resources would have to be resolved, as well as the challenge of obtaining additional funding

Source: Hampton Roads Passenger Rail Study: Phase 2A Norfolk-Richmond Data Collection Final Report, Wetlands for the Petersburg to Norfolk Environmental Study Area (Exhibit 5-7)

High Speed Rail in Virginia

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places