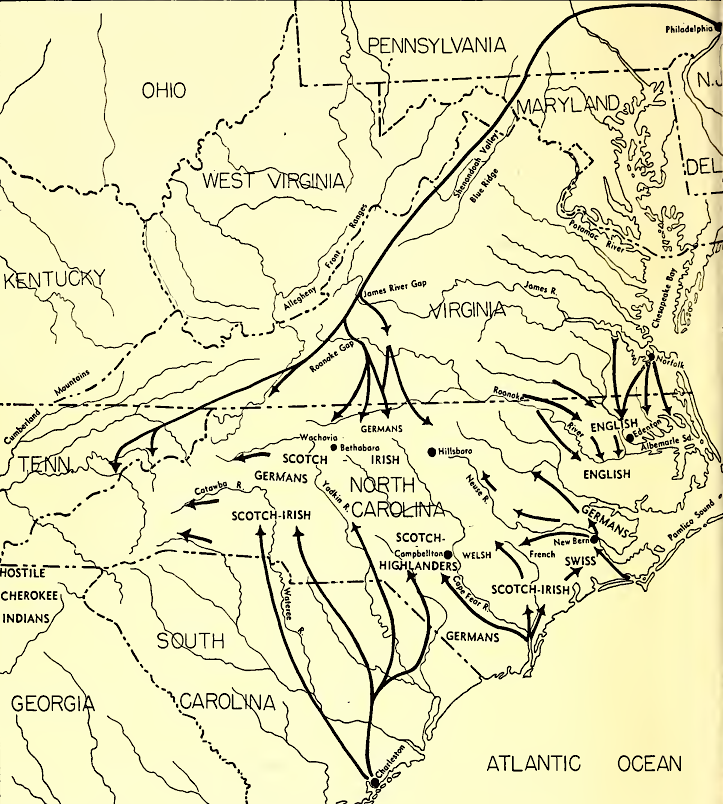

most German-speaking settlers in the 1700's entered Virginia primarily via Pennsylvania, establishing with Scotch-Irish immigrants the Great Wagon Road

Source: Internet Archive, The Influence of Geography Upon Early North Carolina (1963)

most German-speaking settlers in the 1700's entered Virginia primarily via Pennsylvania, establishing with Scotch-Irish immigrants the Great Wagon Road

Source: Internet Archive, The Influence of Geography Upon Early North Carolina (1963)

The death of King Charles II of Spain in 1700 led to the first surge of German-speaking immigrants to Virginia. Charles II had no legitimate children who could inherit the throne. He named as his heir Philip of Anjou, a grandson of Louis XIV of France, but English, Dutch, and Austrian leaders objected to combining the French and Spanish empires.

The resulting military conflict is known in Europe as the War of the Spanish Succession. In North America, the fighting is known as Queen Anne's War. The English, led by former governor of Virginia Francis Nicholson, captured the French fort of Port Royal in 1710 and triggered an exodus of Acadians from Nova Scotia.

In Europe, the fighting in the Rhine River valley helped to trigger an estimated 15,000 residents to flee to England from the Palatinate and other units of the Holy Roman Empire.

Daniel Defoe defined in 1708 why the English should welcome the German-speaking immigrants, even if they were farmers rather than skilled artisans like previous French-speaking Huguenot refugees:1

Virginia officials shared Defoe's perspective. They recognized that the colony needed to attract more workers in order to expand tobacco planting and increase economic activity. By 1700 few people in England were willing to work as indentured servants for years in exchange for transportation to Virginia. The colony respnded by expanding the labor force through importing Africans. Landowners captured all the economic benefits of those workers by enslaving the Africans, rather than paying any wages or allowing them to acquire land on their own. To facilitate perpetual enslavement, General Assembly created a legal system to define chattel slave

Attracting more white colonists from Europe was preferred. Those settlers could be armed and serve in the militia and pay taxes, and their desire to purchase land increased property values in the colonies.

Other colonies shared Virginia's desire to increase immigration from Europe. In 1704, the Carolina Proprietors arranged with a Lutheran minister, Joshua Kocherthal, to publish a book that highlighted the benefits of moving to Carolina. They were competing with William Penn, who was advertising on the continent that land was available in Pennsylvania.

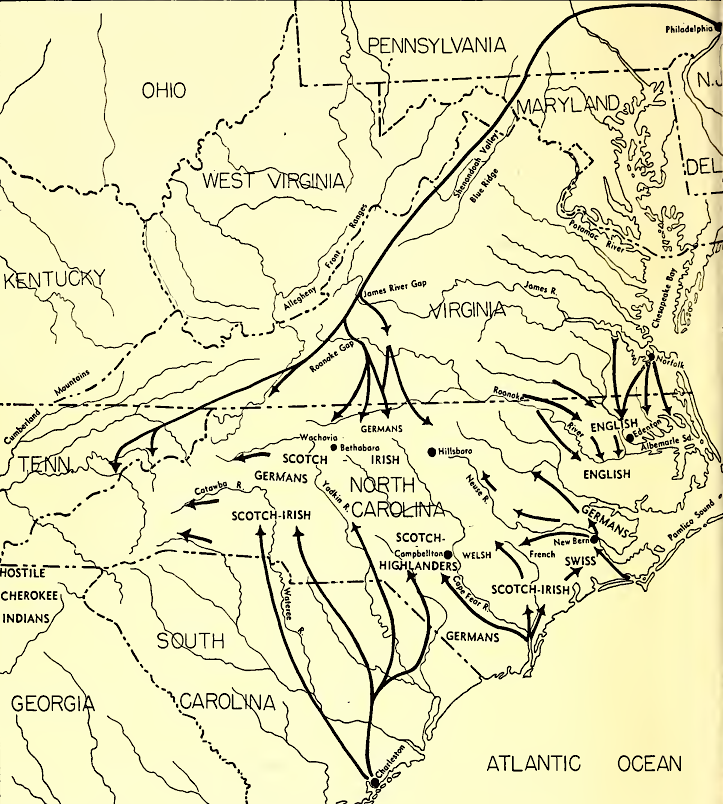

Joshua Kocherthal, who had never visited North America, published A Complete and Detailed Report of the Renowned District of Carolina Located in English America in 1706. He drew material from William Penn's advertisements and information provided to him by the Carolina Proprietors.

In 1708, Kocherthal personally managed to recruit people in the Palatinate to move with him to Carolina. While in England, Kocherthal appealed to Queen Anne and claimed the migrants were fleeing persecution by French Catholics. The queen agreed to sponsor his one group of colonists, financing their transport to North America and promising to continue to support them there. She expected they would cut trees to make masts and other material needed by English ships.

Joshua Kocherthal and 53 migrants traveled across the Atlantic Ocean on the official transport carrying the new Governor of the Province of New York. They sailed up the Hudson River, then unloaded and built the settlement known as Newburgh in 1708.

In Europe, the winter of 1708-09 was the harshest in centuries. The Carolina Proprietors recognized the opportunity and published three editions of Kocherthal's book in 1709. One included a letter from Kocherthal describing how Queen Anne provided free passage for his group of refugees going from England to America. That letter was interpreted in Europe as a promise of a free trip across the Atlantic Ocean and continued support for all future refugees.

The book was circulated widely in the Rhine River valley. Because of the color of ink on the cover, it became known as the "Golden Book." There was a surge of movement from the Rhine River valley to England in 1709, based in the assumption that Queen Anne would finance a trip to the colonies. When Kocherthal returned to London that year, there were thousands of refugees crammed into London in England trying to get to North America.

Palatine refugees flocked to England in 1709, choosing to belive the "Golden Book" promised them free passage to North America

Source: Internet Archive, Aussführlich und umständlicher Bericht von der berühmten Landschafft Carolina, in dem engelländischen America gelegen

England had supported Huguenot refugees after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 forced Protestants to flee France. Three decades later, Queen Anne was willing to support Europeans who had sold their land, furniture, and other assets and were moving primarily for economic opportunity rather than religious repression.

The unexpected influx in 1709 was major news and politically divisive. Whigs who were in charge in 1709 supported the "poor Palatines," while Tories led the opposition. By the end of 1709 the government stopped allowing shiploads of German immigrants into England.

Workers in England viewed the immigrants as unwelcome competition, so there was broad political support to send the refugees to the colonies across the Atlantic Ocean and to Ireland. At the same time, colonial leaders in America sought to recruit those refugees. More farmers and residents would boost the economies of the colonies and increase land values there.

The displaced Protestants were clearly not allies of Catholic Spain or France. Getting those Protestants to settle in the western backcountry would provide a line of defense against Iroquois raids, and help block the French from moving east from the Mississippi River and Ohio River valleys. The Protestants were not Anglicans, but Virginia's leaders were willing to accept some religious diversity in order to get the economic and military benefits of establishing a loyal population in the backcountry.2

an English translation of a 1718 map by Guillaume de L'Isle depicted the English colonies as limited by the Appalachians, leaving the interior open to French claims

Source: Library of Congress, A Map of Louisiana and of the River Mississippi (by John Senex, 1721)

Mixed in with the "poor Palatines" in 1709 were poor Catholics who were economic refugees from parts of the Holy Roman Empire. The Catholics were not welcomed in England.

Queen Anne was the last of the Protestant Stuarts; she had no surviving children to follow her. In 1709 there were legitimate fears that the Catholic son of former King James II would organize an invasion of England rather than let another Protestant assume the throne after she died.

Catholic migrants who arrived in London were forced to convert or sent back to the continent. English objections to the presence of Catholics established a pattern. For the rest of the colonial period, almost all German-speaking immigrants to North America were Protestants.3

The influx forced the government to subsidize transport of the "poor Palatines," as the 1709 letter from Kocherthal had suggested. To clear the migrants out of London, about 2,000 were sent to Ireland.

At Queen Anne's expense, in 1710 a newly-appointed royal governor of New York took 3,000 Protestants to Livingston Manor ninety miles north of New York City on the Hudson River. The Palatines were directed to manufacture tar and other products needed by the Royal Navy and England's merchant fleet. The German-speaking farmers had little expertise in shaping ship masts or manufacturing tar from tree sap. In addition, the trees along the Hudson River do not produce a sap that can be converted into the tar needed for ships and rope. The settlers survived on charity.

Funding to supply their food, promised from England, never arrived. After the Tories in England gained control of the government in 1712, the governor of the colony could no longer provide support. The "poor Palatines" in New York were released from all obligations and left to fend for themselves.4

In 1712-13 the refugees moved to land near Schoharie, which sympathetic Native Americans provided. Clear title to the land could not be obtained, and many migrated again to Pennsylvania in the 1720's at the invitation of Sir William Keith, the governor of Pennsylvania. Some of those German-speaking settlers and their descendants later moved south of the Potomac River and settled in northwestern Loudoun County around Lovettsville. One grandmother of Wilbur and Orville Wright was born in the German Settlement of Loudoun County, and she married a first-generation American who had emigrated from Saxony.5

Virginia failed to capture the wave of migrants in 1709. The Carolina Proprietors succeeded in recruiting a few, in part by demonstrated a "how to lie with maps" approach. The Proprietors had included a map in the third edition of the 1709 version of the Golden Book derived from a previous map made by Nicolaes Vissche. They consciously omitted Virginia settlements to suggest Carolina was a more-settled and attractive location.6

in 1709 the Carolina Proprietors omitted towns in Virginia, suggesting Carolina was a better place for immigrants to settle

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Map of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (by Joshua Kocherthal, 1709)

settlements in Virginia were well-documented before Joshua Kocherthal produced his "golden book" in 1709

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Nova Tabula Geographica complectens Borealiorem Americae Partem (by Nicolaes Visscher, 1698)

The Carolina Proprietors hired away Frantz Ludwig Michel, who had been planning to direct immigrants to Virginia or Pennsylvania. He had visited Virginia in 1702. When Michel met with John Blair in Williamsburg in 1702, Blair offered to sell some of the 10,000 acres owned by the College of William and Mary in Henrico County. Michel chose to examine Manakin, where Huguenots had been settled on the James River upstream of the Fall Line. He obtained a small land grant there before returning to London in 1702.

In 1703 Michel negotiated with William Penn in London. He came back to North America to visit Virginia again and also Pennsylvania in 1704 and 1707.

Michel was a land speculator seeking a grant of free land in order to resettle Anabaptists from the Swiss Canton of Bern. In the early 1700's most European governments sought to block their farmers from migrating. Losing population meant it would be harder to increase the size of the army in time of war. A lower population would reduce prices for land and lower tax revenue.

For a brief moment, however, the local government of Bern, Switzerland saw the export of its poorest people as a benefit. Emigration would shift the burden of pauper support to the English, and also remove religious dissidents from Bern.

Michel submitted a proposal in 1705 to Bern officials to settle 400 to 500 emigrants in Pennsylvania. They forwarded the proposal to English officials, to determine if tey would be supportive. As the Lords of Trade in London considered the proposal, Michel returned to Virginia in 1707. He explored from the Potomac River into the Shenandoah Valley, traveling perhaps as far south as where the town of Edinburg is now located.

Virginia officials welcomed Michel, but were unwilling to give him free land. He finally made a deal in London in 1709. English officials were desperate to move German-speaking migrants out of London, and they approved a proposal to grant land in Virginia to Michel on the same terms the Huguenots had received previously.7

However, Michel abandoned plans to create his own settlement in Virginia or Pennsylvania after he met in London with John Lawson, surveyor general of Carolina, and Baron Christoph von Graffenried, a Swiss nobleman. They became partners in a joint stock company organized by an official in Bern, Georg Ritter. The company agreed to purchase land from the Proprietors, recruit miners in Europe, and create a new settlement along the Neuse River in Carolina.

In 1710 John Lawson led a group of about 600 "poor Palatine" migrants from England to Carolina, while Baron Christoph von Graffenried brought 150 Swiss immigrants from Bern. The ship journeys were rough, and many died before arriving in Carolina.

The survivors did not reach a safe haven in America. They landed at a time when the colony was disrupted by multiple conflicts between Anglicans vs. Quakers and Indian traders vs. farmers seeking to displace the Native Americans. The new settlers in Bath County objected to the traditional control of the colony by Albemarle County residents, and in 1611 Virginia Governor Spotswood sent troops to install a new governor and end the "Cary Rebellion."

Baron von Graffenried went into debt to purchase supplies from Virginia and Pennsylvania. He also provided compensation to the local Native Americans, to minimize their objections to development of New Bern (Bern on the Neuse River).

However, the 1711-1713 Tuscarora War ended the settlement. Lawson and von Graffenried and Lawson were captured in 1711. Lawson was killed, but Baron Christoph von Graffenried was released from captivity.

Michel disappeared in 1713 on the frontier, perhaps killed by the Tuscarora. Baron von Graffenried tried to convince the colonists to move to the Potomac River, but they declined to move. He then transferred his claims to a local Carolina landowner to satisfy outstanding debts, and the colonists lost control of their land. A disappointed von Graffenried returned to Europe in 1713 to seek another opportunity to make a profit from shipping settlers across the Atlantic Ocean.8

The French ended their participation in the War of Spanish Succession in 1713, signing the Treaty of Utrecht. The Habsburgs in Austria made peace a year later. However, there was a continuing desire of German-speaking farmers to move to an English colony.

In 1713, a minister led over 40 miners from Siegen to London. There they met Baron von Graffenried. He arranged space for them on a ship going to Virginia, promising that Governor Alexander Spotswood would cover the transportation costs.

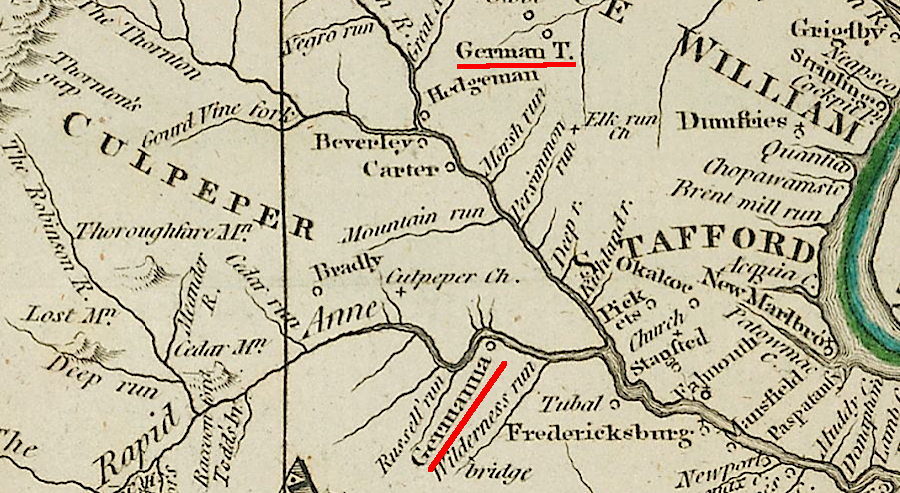

In 1714, the governor was surprised to learn that immigrants had arrived with an expectation that he would pay their transportation debt. The miners agreed to work for him for four years, and he sent them to start Germanna on the Rapidan River.9

German "pietist" groups migrated into Virginia from Pennsylvania starting in the late 1720's.10

They were farmers who lost their crops, houses, and family members in the continuing wars fueled by Catholic and Protestant rivalries. Not surprisingly, their Christian religious beliefs incorporated anti-war beliefs.

Refugees from European wars moved across the Atlantic Ocean to British colonies in North America. William Penn's colony promised religious freedom, and then cheaper land attracted some to the Shenandoah Valley.

Governors Spotswood and Gooch sought to attract new settlers west of the Blue Ridge in the 1720's and 1730's. The language and religious beliefs of those settlers would be different from English-speaking Anglicans east of the Blue Ridge, but the new settlers would be a barrier against French and Native American raiding parties.

Some German-speaking migrants left Pennsylvania after conflicts within their small religious communities. At the Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster County, a monastic group that emphasized celibacy and communal living also struggled with the money-making ambitions of Israel, Samuel and Gabriel Eckerling. The brothers migrated to the New River in 1745-46, joining the Dunkard settlement now underneath Claytor Lake.11

the first German immigrants who left Spotswood's Germanna established Germantown in Fauquier County

Source: Library of Virginia, Alan M. Voorhees Map Collection, A map of the country between Albemarle Sound and Lake Erie (by Thomas Jefferson, 1787)